Abstract

Background

Cenobamate is an antiseizure medication (ASM) approved in the US and Europe for the treatment of uncontrolled focal seizures.

Objective

This post hoc analysis of a phase III, open-label safety study assessed the safety and efficacy of adjunctive cenobamate in older adults versus the overall study population.

Methods

Adults aged 18–70 years with uncontrolled focal seizures taking stable doses of one to three ASMs were enrolled in the phase III, open-label safety study; adults aged 65–70 years from that study were included in our safety analysis. Discontinuations due to adverse events and treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were assessed throughout the study in all patients who received one or more doses of cenobamate (safety study population). Efficacy was assessed post hoc in patients who had adequate seizure data available (post hoc efficacy population); we assessed patients aged 65–70 years from that population. Overall, 100% responder rates were assessed in the post hoc efficacy maintenance-phase population in 3-month intervals. Concomitant ASM drug load changes were also measured. For each ASM, drug load was defined as the ratio of actual drug dose/day to the World Health Organization defined daily dose (DDD).

Results

Of 1340 patients (mean age 39.7 years) in the safety study population, 42 were ≥ 65 years of age (mean age 67.0 years, 52.4% female). Median duration of exposure was 36.1 and 36.9 months for overall patients and older patients, respectively, and mean epilepsy duration was 22.9 and 38.5 years, respectively. At 1, 2, and 3 years, 80%, 72%, and 68% of patients overall, and 76%, 71%, and 69% of older patients, respectively, remained on cenobamate. Common TEAEs (≥ 20%) were somnolence and dizziness in overall patients, and somnolence, dizziness, fall, fatigue, balance disorder, and upper respiratory tract infection in older patients. Falls in older patients occurred after a mean 452.1 days of adjunctive cenobamate treatment (mean dose 262.5 mg/day; mean concomitant ASM drug load 2.46). Of 240 patients in the post hoc efficacy population, 18 were ≥ 65 years of age. Mean seizure frequency at baseline was 18.1 seizures/28 days for the efficacy population and 3.1 seizures/28 days for older patients. Rates of 100% seizure reduction within 3-month intervals during the maintenance phase increased over time for the overall population (n = 214) and older adults (n = 15), reaching 51.9% and 78.6%, respectively, by 24 months. Mean percentage change in concomitant ASM drug load, not including cenobamate, was reduced in the overall efficacy population (31.8%) and older patients (36.3%) after 24 months of treatment.

Conclusions

Results from this post hoc analysis showed notable rates of efficacy in older patients taking adjunctive cenobamate. Rates of several individual TEAEs occurred more frequently in older patients. Further reductions in concomitant ASMs may be needed in older patients when starting cenobamate to avoid adverse effects such as somnolence, dizziness, and falls.

Clinical Trials Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02535091.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This post hoc subgroup analysis of patients aged 65–70 years (n = 15) from a phase III, open-label cenobamate study found notable rates of 3-month interval 100% seizure reduction. |

Treatment-emergent adverse events reported in ≥ 20% of older patients (n = 42) from the safety study population were dizziness, somnolence, fall, fatigue, balance disorder, and upper respiratory tract infection. |

While older patients had similar reductions in concomitant antiseizure medication drug load as the post hoc efficacy population, clinicians should consider greater reductions in older patients to avoid dizziness and falls. |

1 Introduction

The incidence of epilepsy is highest in early childhood and in adults ≥ 65 years of age [1, 2], with the latter group representing the fastest growing segment of the United States (US) population [3]. A diagnosis of new-onset seizures in older adults can be challenging because their symptoms may differ from those in younger patients and/or may mirror the symptoms of other commonly occurring conditions in the older population, such as syncope [4]. New-onset epilepsy in older adults is primarily due to cerebrovascular disease [1, 2]; however, because epilepsy is a lifelong disorder, the older population with epilepsy also includes those who have had the disease for decades.

Several age-related physiological changes, including decreases in lean body mass and decreases in hepatic and renal functioning, can alter the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs in older patients, leading to differences in the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of antiseizure medications (ASMs) [2, 5,6,7]. Comorbidities are also more common with increasing age, leading to polytherapy and an increased potential for drug–drug interactions. In addition, older patients may be more susceptible to some adverse effects of ASMs, such as cognitive disturbances, hyponatremia, balance disorders, and reduced bone mineral density.

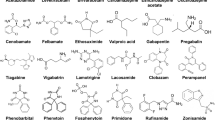

Despite the need to evaluate the effects of ASMs, especially newer ASMs, in the older population, patients over 65 years of age are often not well represented in clinical studies. Cenobamate is an ASM approved in the US (XCOPRI®) [8] and the European Union (ONTOZRY®) [9] as a once-daily treatment for focal seizures in adults. Cenobamate is extensively metabolized and its metabolites are primarily excreted renally [10]. A reduction in dose is recommended when creatinine clearance is ≤ 90 mL/min, and cenobamate is not recommended in end-stage renal disease [8]. Cenobamate reduces plasma concentrations of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A and 2B6 substrates and increases plasma concentrations of CYP2C19 substrates [8]. Dose reductions of several concomitant ASMs metabolized by CYP2C19 (e.g., clobazam, phenytoin, and phenobarbital) are recommended during cenobamate titration [8, 11, 12]. Dose reduction of concomitant lacosamide is also recommended during cenobamate titration to reduce adverse effects due to a potential pharmacodynamic interaction [11, 12].

Clinical studies have demonstrated high responder rates, including 100% seizure reduction, and good tolerability with cenobamate [13,14,15,16,17,18]. These responder rates were sustained for many patients during long-term treatment. In a time-to-event analysis of the phase III, open-label study, 145 patients became seizure-free during the maintenance phase and 62.6% had three or fewer subsequent visits with seizures over a follow-up duration of up to 30 months [19]. The most common adverse events reported in clinical studies were central nervous system (CNS)-related (e.g., dizziness, somnolence, and fatigue). In this post hoc analysis of a large, long-term, phase III, open-label study (NCT02535091), we assessed safety and efficacy in a subgroup of older adults treated with cenobamate in comparison with the overall study population.

2 Methods

2.1 Phase III Safety Study Design and Patients

Details of the original phase III, open-label safety study design have been previously published [15]. Adults aged 18–70 years with uncontrolled focal seizures despite treatment with at least one ASM within the past 2 years were enrolled. Patients must have been taking one to three concomitant ASMs at stable doses. Patients with a previously implanted vagus nerve stimulation device were eligible for inclusion. Patients with a history of drug-induced rash or hypersensitivity reaction were excluded, as were patients with a history of status epilepticus (within 3 months of screening), history of alcohol or drug abuse (within 2 years), clinically significant psychiatric illness or history of suicidal ideation (within 6 months), suicidal behavior (within 2 years), or more than one lifetime suicide attempt. Patients in the study were treated with adjunctive cenobamate initiated at 12.5 mg/day for 2 weeks, which was followed by 25 mg/day for 2 weeks and 50 mg/day for 2 weeks. The dose could then be increased by 50 mg/day at 2-week intervals to a target dose of 200 mg/day (maximum 400 mg/day) [15]. Monotherapy was not allowed. The safety population included 1340 patients who received a dose of cenobamate.

2.2 Post Hoc Efficacy Study Design and Patients

A protocol amendment to the phase III safety study allowed the post hoc collection of seizure data from patient diaries and clinic notes in order to assess changes in seizure frequency, details of which have been previously published [16]. The post hoc efficacy study included a subset of 10 US study sites from the original safety study that had enrolled 11 or more patients and had collected high-quality seizure data. Eligible patients in the post hoc efficacy study population (n = 240) met the following additional requirements: one or more focal aware motor (FAM), focal impaired awareness (FIA), and/or focal to bilateral tonic-clonic (FBTC) seizures in the 3 months prior to the screening visit; seizure data of FAM, FIA, or FBTC while on treatment; consistent raw seizure data documented; and good-quality data for ≥ 85% of the time spent in the study.

The phase III, open-label study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines [15]. Post hoc data collection was approved by an independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board [16]. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient in the phase III study, and no new patient consent was required for the post hoc analyses.

2.3 Older Patient Subgroups and Assessments

This post hoc analysis was conducted retrospectively in the subgroups of older patients aged 65–70 years at baseline from the safety population and the post hoc efficacy population of the phase III study (Fig. 1) [15, 16]. Retention rates were reported at 12, 24, and 36 months in the overall safety population and in patients aged 65–70 years in the safety population using Kaplan–Meier methods. Treatment discontinuations due to adverse events, treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), and serious TEAEs were reported in the open-label study through 36 months in patients aged 65–70 years in the safety population. Adverse events were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 20.0.

Phase III safety study population [15], post hoc efficacy study population [16], and corresponding subgroups of older patients. aPatients with uncontrolled focal seizures who were taking one to three concomitant ASMs were eligible. bPost hoc efficacy population included patients from 10 US study sites that enrolled ≥ 11 patients and had high-quality seizure data. Eligible patients had one or more focal aware motor, focal impaired awareness, and/or focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures in the 3 months prior to the screening visit; seizure data while on treatment; consistent raw seizure data documented; and good-quality data for ≥ 85% of the time spent in the study. ASMs antiseizure medications, US United States

The post hoc efficacy population was used to assess the percentage of patients aged 65–70 years achieving 100% seizure reduction within discrete 3-month intervals during the maintenance phase and at the last available 3-month visit interval. To minimize the impact of reduced patient numbers over time, efficacy was assessed up to month 24 in the 3-month interval analysis. Responder rates (≥ 50%, ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, and 100% seizure reduction) over the entire maintenance phase were also reported.

Concomitant ASM drug load changes from baseline to 24 months were also recorded for each patient, using data from the post hoc efficacy population. Drug load is a method of measuring ASM burden that includes the total doses as well as the number of ASMs a patient is taking. For each drug in a patient’s regimen, the ratio of the actual patient’s ASM dose per day to the drug’s defined daily dose (DDD), a standardized daily maintenance dose provided by the World Health Organization, was calculated [20]. For instance, if a patient was receiving levetiracetam 1500 mg twice daily, their drug load would be the actual daily dose of levetiracetam (3000 mg/day) over the DDD for levetiracetam, which is listed as 1500 mg/day. This would give a drug load of 2. The ratios for each drug in the patient’s regimen were summed to calculate their total ASM drug load.

3 Results

3.1 Patients and Exposure

Of the 1340 patients in the phase III safety population, 42 were aged 65–70 years at study baseline. The mean ages for the phase III safety population and the subgroup of older patients were 39.7 years [15] and 67.0 years, respectively (Table 1). Median duration of exposure was 36.1 and 36.9 months for the phase III safety population and the subgroup of older patients, respectively.

Eighty-eight percent of older patients were taking other non-ASM concomitant medications at baseline. The most frequent medications/drug classes reported in > 15% of older patients were antihypertensive medications (all classes together, 88.1%), calcium and vitamin D drugs and analog (all classes together, 61.9%), statins (28.6%), ibuprofen (23.8%), acetylsalicylic acid (26.2%), paracetamol (21.4%), proton pump inhibitors (21.4%), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (19.0%), multivitamins (16.7%), corticosteroids (16.7%), natural opium alkaloids (16.7%), and thyroid hormones (16.7%).

The percentage of patients remaining on cenobamate at 12, 24, and 36 months following initiation were similar between the overall safety study population (80%, 72%, and 68% at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively) [15] and the subgroup of older patients (76%, 71%, and 69% at 12, 24, and 36 months, respectively) [Fig. 2]. Rates of discontinuation at 36 months due to adverse events were 13.6% (183/1340) in the overall safety study population and 26.2% (11/42) in older patients. The last available median dose of adjunctive cenobamate for both populations was 200 mg/day.

3.2 Safety

TEAEs reported in ≥ 20% of, or in 9 or more, older patients during 36 months of adjunctive cenobamate were dizziness, somnolence, fall, fatigue, balance disorder, and upper respiratory tract infection. Of these TEAEs, dizziness, fall, and balance disorder occurred at a ≥ 10% higher incidence in older patients compared with the overall safety study population (Table 2). Gait disturbance was also more commonly reported in older patients (11.9%) compared with the overall study population (5.4%). Serious TEAEs occurred in 17.8% (238/1340) of patients in the overall safety study population and 28.6% (12/42, n = 1 each) of patients in the older subgroup (Table 2).

Older patients who experienced dizziness and falls did so after a mean 257.6 and 452.1 days, respectively, following cenobamate initiation (Table 3). Patient characteristics for older patients who experienced dizziness and falls at the time of their episodes are reported in Table 3. Additional information on cenobamate dosing and concomitant ASMs for each patient that experienced falls is provided in Table 4.

TEAEs listed under psychiatric disorders, including anxiety (4.1% vs. 7.1%) and insomnia (4.1% vs. 4.8%), were generally comparable between the phase III safety population and older patients.

3.3 Efficacy

Efficacy was assessed during the maintenance treatment phase. There were 214 patients in the phase III post hoc efficacy population who received a dose of cenobamate in the maintenance phase, including 15 older patients. The rate of 100% seizure reduction within any 3-month interval of the maintenance phase increased over time in both the overall post hoc efficacy study population and the subgroup of older patients, to 51.9% (95/183) and 78.6% (11/14), respectively, during months 21–24 (Fig. 3). Rates of 100% seizure reduction (13.1% vs. 13.3%) and ≥ 90% seizure reduction (40.2% vs. 40.0%) over the entire maintenance phase (median duration 29.5 months) were similar among the overall post hoc efficacy maintenance population (n = 214) and subgroup of older patients (n = 15), respectively. The older patient subgroup had numerically higher ≥ 50% (93.3% vs. 75.7%) and ≥ 75% (73.3% vs. 57.5%) responder rates than the overall efficacy population.

3.4 Drug Load

Mean concomitant ASM drug load, not including cenobamate, was lower at baseline in the subgroup of older patients (2.68) than in the overall post hoc efficacy study population (3.57) (Fig. 4). Concomitant ASM drug load reductions occurred over time in both groups. At 12 months, the concomitant ASM drug load was reduced by 29.4% in the post hoc efficacy population and 31.2% in older patients, and at 24 months, the concomitant ASM drug load was reduced by 31.8% in the post hoc efficacy population and by 36.3% in older patients. Among the 42 older patients, 16.7%, 42.9%, and 40.5% were taking 1, 2, and >2 concomitant ASMs, respectively, at baseline. At 36 months of follow-up, 19% (n = 8), 31% (n = 13), and 7.1% (n = 3) of older patients were taking 1, 2, and > 2 concomitant ASMs, respectively.

4 Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of older epilepsy patients with focal seizures, efficacy findings indicated a similar response to adjunctive cenobamate in older patients and the overall post hoc efficacy study population, with high rates of seizure reduction noted in both groups. Robust seizure reduction rates (e.g., ≥ 50% seizure reduction) in subanalyses of older patients have also been reported with other ASMs, such as brivaracetam [21, 22]. Specific considerations for ASM use in older patients with epilepsy include developmental changes associated with aging; increased polytherapy, including non-epilepsy drugs; and increased potential for drug–drug interactions and adverse medication effects [4].

Monitoring the effects of long-term ASMs on balance and the likelihood of falls, along with changes in cognition, are important for older patients [23]. During the 3-year treatment duration, older patients experienced a higher incidence of several TEAEs during long-term adjunctive cenobamate treatment compared with the overall safety study population, including dizziness (42.9%, 18/42), falls (29.3%, 12/42), and balance disorder (21.4%, 9/42). A subanalysis of perampanel in older patients (≥ 65 years of age, n = 20) with epilepsy from pooled, randomized, phase III studies also reported higher frequencies of adverse events, including dizziness and falls, during 19 weeks of treatment compared with adults 18–64 years of age [24]. The rates of dizziness and falls were 45% and 25% in the ≥ 65 years perampanel subgroup compared with 29% and 5% in the < 65 years perampanel subgroup, respectively. Falls are common in the older population and are of particular concern due to the prevalence of age-related decreases in bone density [2, 5]. According to a meta-analysis of 104 studies that included 1,741,613 people throughout the world, the prevalence of falls in older people was 26.5%. A systematic review of ASM use in older populations for any indication, not just epilepsy, noted an association between the use of any ASM and an increased risk of falls, with adjusted effect estimates ranging from a hazard ratio of 1.31 (i.e., a 31% increased risk) to an odds ratio of 2.8 (i.e., almost threefold increased odds) [25].

Older patients are also more likely to be taking a higher number of non-epilepsy medications, such as cardiovascular drugs, anticoagulants, antidiabetes drugs, etc., leading to a greater potential for drug–drug interactions that can increase the risk of dizziness. Considerations for starting cenobamate in older patients, like other ASMS, should include an assessment of comorbidities and all concomitant medications. In older patients with epilepsy, it is advisable to start an ASM with a low dose and titrate slowly to improve tolerability [7]. A lower maintenance dose of cenobamate should also be used if possible. Due to decreased creatinine clearance with age, particularly among women, an upper limit of cenobamate 200 mg/day should be considered in patients ≥ 65 years of age. Data from previous studies have shown that clearance of nearly all ASMs is reduced by approximately 20–50% on average in older patients in comparison with their younger counterparts, suggesting that doses should be up to 50% lower in older patients [7].

These recommendations are in line with our suggestions to start cenobamate at a low dose and slowly titrate to a low maintenance dose (200 mg/day). It may also be beneficial to assess fall risk in older patients before and during cenobamate treatment, as with other ASMs. These safety considerations should also be balanced with the risk of falls due to ongoing seizures.

The reduction of concomitant ASMs after the introduction of a new ASM, such as cenobamate, is an important goal to limit the number and severity of potential TEAEs [11, 12]. In this post hoc analysis, older patients had similar concomitant ASM drug load reductions compared with the overall study population after adding cenobamate. Previous data from the phase III study showed that concomitant ASM dose reductions frequently occurred following cenobamate initiation [12]. For instance, the dose of clobazam was reduced by 65.8% in patients who remained on cenobamate. Consensus recommendations for adding cenobamate to an ASM regimen include proactive dose adjustments of several concomitant ASMs that have pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interactions with cenobamate, including phenytoin, phenobarbital, clobazam, and lacosamide [11]. Clinicians should consider a more aggressive, proactive reduction of concomitant ASM drug load reduction in older patients in order to reduce the risk of dizziness and falls in older patients.

The strengths of this study include the relatively long study duration, allowing analysis of safety and efficacy up to 36 and 24 months, respectively. Responder rates, including 100% seizure reduction, were also reported across the entire maintenance phase, with a median duration of approximately 2.5 years. Limitations of the study include the small number of older patients in the safety (n = 42) and efficacy subgroups (n = 18). The post hoc, retrospective analysis is another limitation, and there is a possibility of selection bias associated with the open-label study design. Older adults are a heterogenous population and in a controlled study such as this, including strict inclusion/exclusion criteria, we may fail to observe certain challenges that have been found in real-world observations of older patients treated for epilepsy, such as lack of adherence to a treatment regimen or increased risk of dosing errors due to a decline in memory [23]. This may limit the generalizability of the study. The age cut-off for the study (70 years) also limits the generalizability somewhat, as there are many epilepsy patients >70 years of age who may face different sets of challenges. Additional analyses of ASMs such as cenobamate in a larger population of older patients, including age-stratified groups, severity and timing of adverse events, and their associations with specific concomitant ASMs, will help further inform clinicians. Furthermore, although the study design allowed for dose adjustments, which may be more reflective of real-world practice, cenobamate monotherapy was not allowed. While the older patients enrolled in this study had uncontrolled seizures despite treatment with one to three ASMs, many older patients, particularly those with newly diagnosed epilepsy, may be successfully managed with monotherapy. Future prospective research is needed to provide more guidance on the use of cenobamate in older patients, ideally following the suggestions for cenobamate dosing and dose adjustments of concomitant ASMs set out in this study.

5 Conclusions

Dizziness, falls, fatigue, balance disorder, and gait disturbance occurred more frequently in a small subset of older patients than in the overall phase III population during 36 months of open-label cenobamate treatment. Efficacy, measured by 100% seizure reduction over 3-month intervals, indicated a similar response to adjunctive cenobamate in the smaller subset of older patients compared with the overall post hoc efficacy study population. Older patients and the post hoc efficacy population also had similar reductions in mean concomitant drug load, despite a lower initial drug load for older patients. Based on these findings, a more aggressive, proactive reduction of concomitant ASMs, particularly sodium channel blockers, is recommended to reduce the risk of adverse effects such as somnolence, dizziness, and falls when adding on cenobamate. A lower maintenance dose of cenobamate (200 mg/day) may also be advisable for some older patients.

References

Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34(3):453–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x.

Leppik IE, Walczak TS, Birnbaum AK. Challenges of epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet. 2012;380(9848):1128–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61517-7.

Roberts AW, Ogunwole SU, Blakeslee L, Rabe MA, US Census Bureau. The Population 65 Years and Older in the United States: 2016. American Community Survey Reports. 2018. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/acs/ACS-38.pdf. Accessed 9 Dec 2022.

Lee SK. Epilepsy in the elderly: treatment and consideration of comorbid diseases. J Epilepsy Res. 2019;9(1):27–35. https://doi.org/10.14581/jer.19003.

Motika PV, Spencer DC. Treatment of epilepsy in the elderly. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016;16(11):96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-016-0696-8.

Perucca E, Berlowitz D, Birnbaum A, et al. Pharmacological and clinical aspects of antiepileptic drug use in the elderly. Epilepsy Res. 2006;68(Suppl 1):S49–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.017.

Roberti R, Palleria C, Nesci V, et al. Pharmacokinetic considerations about antiseizure medications in the elderly. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020;16(10):983–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425255.2020.1806236.

XCOPRI® (cenobamate tablets), for oral use, CV [prescribing information]. Paramus: SK Life Science, Inc.; 2024.

Ontozry [summary of product characteristics]. Rome: Angelini Pharma S.p.A; 2023.

Vernillet L, Greene SA, Kim HW, Melnick SM, Glenn K. Mass balance, metabolism, and excretion of cenobamate, a new antiepileptic drug, after a single oral administration in healthy male subjects. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2020;45(4):513–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13318-020-00615-7.

Smith MC, Klein P, Krauss GL, et al. Dose adjustment of concomitant antiseizure medications during cenobamate treatment: expert opinion consensus recommendations. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:1705–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-022-00400-5.

Rosenfeld WE, Abou-Khalil B, Aboumatar S, et al. Post-hoc analysis of a phase 3, multicenter, open-label study of cenobamate for treatment of uncontrolled focal seizures: effects of dose adjustments of concomitant antiseizure medications. Epilepsia. 2021;62(12):3016–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17092.

Chung SS, French JA, Kowalski J, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures. Neurology. 2020;94(22):e2311–22. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000009530.

Krauss GL, Klein P, Brandt C, et al. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive cenobamate (YKP3089) in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(1):38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30399-0.

Sperling MR, Klein P, Aboumatar S, et al. Cenobamate (YKP3089) as adjunctive treatment for uncontrolled focal seizures in a large, phase 3, multicenter, open-label safety study. Epilepsia. 2020;61(6):1099–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.16525.

Sperling MR, Abou-Khalil B, Aboumatar S, et al. Efficacy of cenobamate for uncontrolled focal seizures: post-hoc analysis of a phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. Epilepsia. 2021;62(12):3005–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17091.

Klein P, Aboumatar S, Brandt C, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety from an open-label extension of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures. Neurology. 2022;99(10):e989–98. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000200792.

French JA, Chung SS, Krauss GL, et al. Long-term safety of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures: open-label extension of a randomized clinical study. Epilepsia. 2021;62(9):2142–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17007.

Vossler DG, Rosenfeld WE, Stern S, et al. Sustainability of seizure reduction and seizure control with adjunctive cenobamate: post-hoc analysis of a phase 3, open-label study. Epilepsia. 2023;64(10):2644–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17724.

Reinhardt F, Weber YG, Mayer T, et al. Changes in drug load during lacosamide combination therapy: a noninterventional, observational study in German and Austrian clinical practice. Epilepsia Open. 2019;4(3):409–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/epi4.12346.

Brodie MJ, Whitesides J, Schiemann J, D’Souza J, Johnson ME. Tolerability, safety, and efficacy of adjunctive brivaracetam for focal seizures in older patients: a pooled analysis from three phase III studies. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:114–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.018.

Ben-Menachem E, Mameniskiene R, Quarato PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of brivaracetam for partial-onset seizures in 3 pooled clinical studies. Neurology. 2016;87(3):314–23. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000002864.

Piccenna L, O’Dwyer R, Leppik I, et al. Management of epilepsy in older adults: a critical review by the ILAE Task Force on Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia. 2023;64(3):567–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.17426.

Leppik IE, Wechsler RT, Williams B, Yang H, Zhou S, Laurenza A. Efficacy and safety of perampanel in the subgroup of elderly patients included in the phase III epilepsy clinical trials. Epilepsy Res. 2015;110:216–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.11.015.

Haasum Y, Johnell K. Use of antiepileptic drugs and risk of falls in old age: a systematic review. Epilepsy Res. 2017;138:98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.10.022.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sarah Mizne, PharmD, Mari Willeman, Ph.D., and Don Fallon, ELS, of MedVal Scientific Information Services, LLC, for medical writing and editorial assistance, which were funded by SK Life Science, Inc. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ “Good Publication Practice (GPP) Guidelines for Company-Sponsored Biomedical Research: 2022 Update.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Previous presentation

O’Dwyer R, et al. Safety and efficacy of cenobamate for the treatment of focal seizures in older patients. Presented at the American Epilepsy Society 2022 Annual Meeting, 2–6 December 2022, Nashville, TN, USA (Poster 1.292) and encored at the American Academy of Neurology 2023 Annual Meeting, 22–27 April 2023, Boston, MA, USA (Poster P4.002).

Funding

This study was supported by SK Life Science, Inc.

Conflicts of interest

Rebecca O’Dwyer is a consultant/advisor for SK Life Science, Inc. Sean Stern, Clarence T. Wade, and Anuradha Guggilam are employees of SK Life Science, Inc. William E. Rosenfeld is a consultant/advisor for SK Life Science, Inc.; speaker for SK Life Science, Inc.; and has received research support from SK Life Science, Inc. and UCB Pharma.

Ethics approval

The original phase III study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of Good Clinical Practice, according to the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines and all applicable country-specific regulations. The study protocol was approved by an independent Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board at each site according to local regulations.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the original phase III study; no new patient consent was required for this post hoc analysis.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data for the analyses described in this manuscript are available by request from the corresponding author or SK Life Science, Inc., the company sponsoring the clinical development of cenobamate for the treatment of focal epilepsy.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: RO, SS, CTW, AG, and WER. Acquisition of data: SS, CTW, and WER. Statistical analysis: SS and CTW. Data interpretation: RO, SS, CTW, AG, and WER. All authors were involved in critically revising the manuscript, reviewed the final manuscript, and gave approval for submission.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Dwyer, R., Stern, S., Wade, C.T. et al. Safety and Efficacy of Cenobamate for the Treatment of Focal Seizures in Older Patients: Post Hoc Analysis of a Phase III, Multicenter, Open-Label Study. Drugs Aging 41, 251–260 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01102-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-024-01102-3