Abstract

Introduction

Despite new anti-seizure medications (ASMs) being introduced into clinical practice, about one-third of people with epilepsy do not reach seizure control. Cenobamate is a novel tetrazole-derived carbamate compound with a dual mechanism of action. In randomized controlled trials, adjunctive cenobamate reduced the frequency of focal seizures in people with uncontrolled epilepsy. Studies performed in real-world settings are useful to complement this evidence and better characterize the drug profile.

Methods

The Italian BLESS (“Cenobamate in Adults With Focal-Onset Seizures”) study is an observational cohort study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of adjunctive cenobamate in adults with uncontrolled focal epilepsy in the context of real-world clinical practice. The study is ongoing and conducted at 50 centers in Italy. This first interim analysis includes participants enrolled until June 2023 and with 12-week outcome data available.

Results

Forty participants with a median age of 36.5 (interquartile range [IQR] 26.0–47.5) years were included. The median monthly seizure frequency at baseline was 6.0 (IQR 2.5–17.3) seizures and 31 (77.5%) participants had failed four or more ASMs before cenobamate. At 12 weeks from starting cenobamate, the median reduction in monthly seizure frequency was 52.8% (IQR 27.1–80.3%); 22 (55.0%) participants had a ≥ 50% reduction in baseline seizure frequency and six (15.0%) reached seizure freedom. The median number of concomitant ASMs decreased from 3 (IQR 2–3) at baseline to 2 (IQR 2–3) at 12 weeks and the proportion of patients treated with > 2 concomitant ASMs decreased from 52.5% to 40.0%. Seven (17.5%) patients reported a total of 12 adverse events, 11 of which were considered adverse drug reactions to cenobamate.

Conclusion

In adults with uncontrolled focal seizures, the treatment with adjunctive cenobamate was well tolerated and was associated with improved seizure control and a reduction of the burden of concomitant ASMs.

Trial Registration Number

NCT05859854 (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BLESS is an observational, multicenter, cohort study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of cenobamate in adults with uncontrolled focal epilepsy in the context of real-world clinical practice. |

This first interim analysis focused on 12-week outcomes and included 40 participants. |

At 12 weeks from cenobamate treatment initiation, 55.0% of participants were ≥ 50% responders and 15.0% achieved 100% seizure reduction. |

The median number of concomitant anti-seizure medications decreased from 3 at baseline to 2 at 12 weeks. |

Cenobamate demonstrated a favorable tolerability profile and adverse events occurred in 17.5% of the participants. |

Introduction

Epilepsy is a neurologic condition associated with physical, psychological, and social burdens on people with epilepsy (PwE) and their caregivers. PwE can have their quality of life (QoL) negatively affected by multiple factors, including frequent seizures, long seizure duration, the presence of comorbidity and psychiatric disorders, and social limitations linked to fear of upcoming seizures, stigma, and employment concerns [1]. A recent review concluded that PwE who better respond to and tolerate anti-seizure medications (ASMs) have significant QoL improvements, suggesting that achieving and maintaining seizure freedom should be the ultimate goal in epilepsy management [1, 2].

ASMs represent the mainstay of treatment of epilepsy [3]. Despite the large number of new ASMs introduced into clinical practice over the last decades, about one-third of PwE do not achieve freedom from seizures [4]. Therefore, the search for new effective treatments represents an important unmet need.

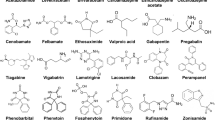

Cenobamate is a novel tetrazole-derived carbamate compound. The drug was approved in 2021 by the European Medicines Agency for the adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures, with or without secondary generalization, in adult PwE who have not achieved adequate seizure control despite receiving treatment with at least two ASMs [5]. Cenobamate demonstrated its efficacy in two randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs), and it was associated with a seizure-free rate of 21.0% after 12 weeks of treatment when given at 400 mg/day [6, 7]. These results were confirmed by the open-label extension and long-term safety studies [8,9,10]. The most frequent treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) reported during the RCTs and their extensions were generally mild-to-moderate in intensity, related to the central nervous system, and dose-dependent. The strict eligibility criteria, the short duration of treatment, and the little flexibility in the adjustment of concomitant ASMs, however, hinder the generalizability of the findings of RCTs to everyday clinical practice. In this regard, studies performed in a real-world setting are useful to complement the evidence obtained in pivotal trials and better characterize the drug profile.

The Italian “Cenobamate in Adults With Focal-Onset Seizures” (BLESS) Study [ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05859854] is an ongoing, multicenter, observational cohort study aimed to evaluate the 52-week effectiveness, tolerability, and safety of adjunctive cenobamate in adults with uncontrolled focal epilepsy in the context of real-world clinical practice.

Here, we present the results of the first interim analysis focused on 12-week outcomes.

Methods

Study Design and Participant Identification

The BLESS Study is a multicenter, observational, retrospective and prospective cohort study. The study is performed at 50 sites in Italy, began on January 24, 2023 (first patient in), and is expected to be completed in 2025 (last patient out). The estimated number of participants is 1200.

The study enrolls consecutive PwE treated with cenobamate as per standard clinical practice. Study participation does not influence treatment decisions, which are made independently by the treating physicians, in accordance with their routine clinical practice. Participants are male or female adults (age ≥ 18 years) with uncontrolled focal epilepsy despite treatment with at least two ASMs before cenobamate initiation. All participants at enrollment must have been treated with adjunctive cenobamate for at least 12 weeks (i.e., the titration period up to the initial recommended target dose of 200 mg daily) but no more than 52 weeks. Participants who received adjunctive cenobamate but discontinued it within the first 12 weeks of treatment are not eligible. Exclusion criteria include the diagnosis of familial short-QT syndrome, hypersensitivity to cenobamate (or to any of the excipients), and history of severe drug-induced hypersensitivity reaction, including drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) and Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

All participants receive a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures and objectives, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and participate in the study voluntarily following the signing of a written informed consent form. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating institutions before the start of data collection (first approval of the Coordinating Ethics Committee—Comitato Etico IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Neuromed—on September 29, 2022; see Supplementary 3—Table S2), and conducted under the guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP) and applicable regulatory requirements [11].

Data Collection

Data from the initiation of cenobamate treatment (index date) to the enrollment visit are collected retrospectively. After the enrollment visit, the observation is prospective for up to 52 (+4) weeks. Accordingly, the maximum duration of observation is 104 (+4) weeks after the index date, or until withdrawal. For each participant, data collection is expected at five time points after cenobamate initiation: week 12 (+4 weeks), week 24 (±4 weeks), week 52 (±4 weeks), week 76 (±4 weeks), and week 104 (±4 weeks). Data available in medical charts and patient seizure diaries aligned with the study objectives are collected through an electronic case report form (eCRF).

The ongoing medical conditions at the index date, when available in medical chart, were retrospectively collected and reported in this preliminary interim analysis. Moreover, the study prospectively evaluates the status of patient's health-related QoL (HRQoL), global functioning, sleepiness, anxiety, and depression using the following questionnaires and scales: 31-item Quality Of Life In Epilepsy Inventory (QOLIE-31), Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scales, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

All adverse events (AEs) that occurred in patients treated with cenobamate (i.e., collected from cenobamate treatment initiation to end of observation: study completion date or early withdrawal date, irrespective of the reason) were summarized by frequency, causality, severity, outcome, seriousness, and action taken concerning cenobamate treatment, according to the judgment of the treating physician.

The AEs were registered in a dedicated eCRF form according to the medical charts. To minimize issues in pharmacovigilance reporting, both on-site and remote study monitoring is performed during the study, according to protocol and applicable regulations: guidelines for GPP [11], European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance (ENCePP), Guide on Methodological Standards in Pharmacoepidemiology.

Primary Outcomes

According to the primary objective (see Supplementary 2), the primary effectiveness outcomes include the intra-patient percent change and the proportion of participants with a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly seizure frequency from the pre-treatment baseline over 52 weeks (Supplementary 2).

Secondary and Explorative Outcomes

Secondary outcomes include (1) the proportion of participants with a ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, or 100% reduction and (2) the proportion of participants with a ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, or 100% sustained reduction in monthly seizure frequency from the pre-treatment baseline over 52 weeks (Supplementary 2).

The safety and tolerability of cenobamate as an adjunctive treatment are also evaluated by describing the absolute and relative frequency of patients who experienced at least one AE/adverse drug reaction (ADR) to cenobamate during the applicable observation period, and the total number of AEs/ADRs that occurred. The AEs were described according to MedDRA®: the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities terminology is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). The MedDRA® trademark is registered by ICH.

The above-mentioned secondary outcomes were evaluated in the current interim analysis. The full list of study objectives and outcomes, including the assessment of the patients' HRQoL as per questionnaires and scales reported in Sect. 2.2, as planned in the study protocol, is reported in Supplementary 2 and will be described in future analyses.

Data are analyzed overall and according to age group, cenobamate treatment setting, final target daily dose of cenobamate prescribed, and the number of concomitant ASMs.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size is defined according to feasibility considerations. Further information can be found in Supplementary 2. No formal hypotheses are set for this observational study, due to its descriptive aim.

Descriptive statistics were given for all evaluable participants. Categorical variables were displayed for frequency count and percentage, and continuous variables were reported as number of observations, mean and standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR).

In this first interim analysis, only participants who were enrolled until June 30, 2023 (database extraction date) and had 12-week seizure frequency data available were included. The effectiveness, tolerability, and safety were evaluated from the index date to 12 weeks.

According to the study protocol, the seizure frequency during the pre-treatment baseline (i.e., the number of seizures experienced during the previous 12 weeks with respect to the index date, if available) and the post-baseline assessments, was obtained by summing the total number of seizures (all types of seizures) reported in each considered period and dividing it by the duration of that period (number of days), excluding days with no available data. The counted seizures were multiplied by 28 to normalize to a 4-week rate (“monthly seizure frequency”). The data about seizure frequency were obtained from the medical chart or patient diary.

Analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 8.2 and SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Study design and conduct, data monitoring, eCRF setup, and statistical analyses were performed by Medineos SRL (Modena, Italy), a company subject to the direction and coordination of IQVIA Ltd., on behalf of Angelini Pharma.

Results

Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

At the time of this interim analysis, 7 of 50 planned sites were authorized for study initiation. Among the 58 PwE enrolled, 40 were eligible (responding to inclusion and exclusion criteria) and had data on seizure frequency at 12 weeks available (see Supplementary 2—Fig. S1).

The median (IQR) age of participants was 36.5 (26.0–47.5) years, and 55.0% (n = 22) were female. The median (IQR) age at diagnosis of epilepsy was 18 (8.0–37.0) years. The baseline median (IQR) monthly seizure frequency was 6.0 (2.5–17.3) seizure episodes.

A total of 17 (42.5%) participants had comorbidities: the most frequent were anxiety (n = 4; 10.0%), depression (n = 3; 7.5%), and obesity (n = 3; 7.5%). The main etiology of epilepsy was structural (n = 22; 55.0%). The baseline characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Cenobamate and Concomitant ASMs

The median (IQR) number of previous ASMs was 8.0 (4.0–11.5). Most participants (n = 31, 77.5%) had tried four or more ASMs before cenobamate, including sodium channel blockers in 39 (97.5%) cases. Among the included participants, 10.0% (n = 4) initiated cenobamate within the Italian Compassionate Use Program (CUP). The cenobamate daily dose at 12 weeks was 200 mg in 30 out of 37 (81.1%) and less than 200 mg in 7 out of 37 (18.9%) participants; data were missing in three cases (Table 1).

The median (IQR) number of concomitant ASMs decreased from 3.0 (2.0–3.0) at the time of starting cenobamate to 2.0 (2.0–3.0) at 12 weeks (Table 2). Analyzing the number of concomitant ASMs for each participant, the percentage receiving treatment with > 2 concomitant ASMs decreased over the 12 weeks from 52.5% to 40.0%; benzodiazepine derivatives and barbiturates were the most frequently discontinued treatments after 12 weeks, followed by carboxamide and hydantoin derivatives (Table 2).

Effectiveness of Adjunctive Cenobamate

The median (IQR) number of monthly seizures was 6.0 (2.5–17.3) at baseline and 3.8 (1.2–7.6) at 12 weeks. Overall, the median (IQR) percentage reduction in monthly seizure frequency at 12 weeks versus the index date was 52.8% (27.1–80.3%) (Fig. 1).

Twenty-two (55.0%; 95% confidence interval [CI] 38.5–70.7) participants had a ≥ 50% reduction in baseline monthly seizure frequency, and six (15.0%; 95% CI 5.7–29.8) were seizure-free at 12 weeks. The rates of participants with ≥ 75% and ≥ 90% reduction in baseline seizure frequency at 12 weeks were 27.5% (n = 11; 95% CI 14.6–43.9) and 20.0% (n = 8; 95% CI 9.1–35.7), respectively (Fig. 2).

Rates of ≥ 50%, ≥ 75%, ≥ 90%, and 100% reduction in monthly seizure frequency from the pre-treatment baseline to 12 weeks. Percentages were computed over the total number of participants with available intra-patient percent change in monthly seizure frequency at the time point of interest versus pre-treatment baseline monthly seizure frequency (N = 40). PwE people with epilepsy, CI confidence interval

Tolerability and Safety of Adjunctive Cenobamate

During the first 12 weeks of treatment with cenobamate, 12 AEs were recorded in 7 out of 40 (17.5%) participants. Among the AEs, 11 events were ADRs to cenobamate and one was an AE with no suspected causal relationship with cenobamate treatment (pruritus). The ADRs were mild (n = 8) or moderate (n = 3) and in 72.7% of the cases (n = 8) there was no need to change the cenobamate dosage. The most common ADR was somnolence (n = 3, 7.5%). The full description according to MedDRA® Version 26.0, March 2023, is in Table 3. No serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported.

Discussion

This interim analysis presented the preliminary results of the BLESS Study in a subset of 40 evaluable patients at the first assessment time point of 12 weeks after the initiation of cenobamate treatment. Cenobamate, administered in addition to other ASMs, was associated with a median reduction in monthly seizure frequency of 52.8%. Among the study participants, 55.0% had a ≥ 50% reduction in baseline seizure frequency and 15.0% were seizure-free at 12 weeks. Of note, the baseline characteristics of the PwE enrolled so far in the BLESS Study suggest they had difficult-to-treat epilepsies: the median number of ASMs before the index date was 8.0, and 70.0% of participants were treated with ≥ 5 ASMs before initiating cenobamate. Therefore, this first preliminary analysis showed that cenobamate seems to have good effectiveness in the real-world setting, with results consistent with the pivotal trial, even in participants who experienced many treatment failures. These preliminary effectiveness data are consistent with those of pivotal clinical trials and observational studies. In the work of Krauss and colleagues, the median percent reduction in seizure frequency was 55.0% in the cenobamate group, and 56.0% of participants were ≥ 50% responders [6]. Recently, some real-world studies provided evidence about cenobamate treatment in different settings. The analysis of real-world data from the Spanish Expanding Access Program revealed a median reduction in seizure frequency of 55.1% at 12 weeks, with 58.8% of participants being ≥ 50% responders [13]. In the real-world study by Beltrán-Corbellini and colleagues, the median 12-week reduction in seizure frequency was 51.0%, and the 50% responder rate was 56.5% [14]. In a recent meta-analysis of seven observational studies including 229 PwE treated with cenobamate, the rates of seizure reduction > 50% and seizure freedom were 68.0% and 16.2%, respectively [15]. Moreover, cenobamate induced a substantial reduction in focal-onset seizures after a 3-month treatment. This effect lasted for 6 months in strong responders (PwE with ≥ 75% seizure reduction) [2]. Other observational studies showed that cenobamate reduced focal seizure frequency in adults living with developmental disability [16] and in those with highly refractory focal epilepsy in Spain [13, 14, 17] and in Italy [18].

After 12 weeks of cenobamate treatment, the participants in the BLESS Study showed a reduction in the median number of concomitant ASMs. This trend was confirmed by the percentage of patients treated with three to five ASMs, which consistently decreased from the index date to 12 weeks. Despite the small sample size, this outcome is in line with other evidence from clinical practice collected in other real-world studies [13, 14, 17]. An Italian observational study showed a reduction or withdrawal of one or more concomitant ASMs in 59.2% of cases [18].

Decreasing the number or the dose of concomitant ASMs is a recommended goal to reduce drug burden, prevent possible AEs related to drug–drug interactions, and allow for optimal cenobamate dosing [19, 20]. In a consensus panel of experts, Smith and colleagues suggested proactively lowering the dose of concomitant ASMs, rather than discontinuing the newly added ASM, at least until the minimum effective dose is reached and the potential seizure control might be measurable. Once the cenobamate dose is 200 mg/day and if PwE achieve marked improvement or seizure freedom, reduction or removal of concomitant ASMs should be considered [20].

Minimizing AEs is crucial in ASM therapy. This allows for better treatment adherence and, in the end, reduces costs related to managing AEs and improves QoL. Cenobamate was generally well tolerated, and the safety profile that emerged from this preliminary evaluation of the BLESS Study data was consistent with that from previous studies [15]. The main AEs were somnolence, psychomotor retardation, and vertigo. No SAE occurred and no new safety events were identified within 12 weeks of treatment. According to clinical experience, a suggested strategy to manage ADR is to review the treatment approach in light of the patient’s profile. Some healthcare professionals suggest administering the therapy in the evening to mitigate the somnolence; another option is to lower the dose of concomitant ASMs, especially benzodiazepine (to mitigate somnolence) or sodium channel blockers, which can cause dizziness. This approach may reduce the potential synergic adverse effects of cenobamate [19, 21]. Therefore, reducing concomitant ASMs can help to manage the AEs related to cenobamate and is widely recommended [20]. It is important to note that the titration phase, beginning with a low dose of cenobamate (12.5 mg) and progressing to 200 mg at 12 weeks, demonstrated to mitigate the risk of DRESS [8,9,10, 19, 21]. Accordingly, no cases of DRESS were recorded in this interim preliminary analysis.

Although the results of this interim analysis look promising, it will be crucial to assess the effectiveness and safety outcomes in a larger population and over a longer follow-up. Indeed, there are some limitations to the current analysis. First, at the time of data extraction, only 7 out of 50 planned sites were authorized for study initiation, and out of the participants enrolled at the time of data cutoff, some were not evaluable due to incomplete 12-week data. This eventually reduced the number of PwE involved in this analysis to about 3.0% of the 1200 expected to be enrolled in the study and reduced the geographical distribution of the data collection, potentially increasing a selection bias. These very preliminary results should be considered purely descriptive and not suitable for statistical analysis of significance, which will be performed in the future when a larger real-world population will be recruited. Second, due to the observational nature of the study, the seizure counts may not be as accurate and detailed as in clinical trials. However, to mitigate this circumstance, the study requires among the inclusion criteria, the availability in medical charts or seizure diaries of relevant data, such as the number of seizures at defined intervals. It is also worth noting that the protocol does not require the collection of seizure frequency by seizure type. For this reason, the BLESS Study will not evaluate the effectiveness of cenobamate according to the seizure characteristics. In addition, the study included only patients who completed at least 12 weeks of treatment with cenobamate. Since the early (< 12 weeks) discontinuation of cenobamate is unlikely to be related to a lack of therapeutic efficacy, the potential bias introduced by the exclusion of patients who did not complete the titration period is not expected to significantly affect the effectiveness outcomes. Instead, the collection of AEs based on records of clinical visits rather than standardized questionnaires and the inclusion of patients only after 12-week treatment might lead to underreporting of AEs. Therefore, the potential impact on tolerability outcomes (secondary objective) cannot be ascertained. Nevertheless, the BLESS Study includes patients who received adjunctive cenobamate for at least 12 weeks and discontinued the treatment before enrollment. The reason for permanent discontinuation will be recorded. Lastly, to reduce the selection bias, all participants meeting the eligibility criteria are consecutively considered for inclusion.

On the other side, the major strengths of the BLESS Study will include the large sample size, the long-term follow-up, and the assessment of the impact of cenobamate treatment on different clinical outcomes. The study will evaluate the HRQoL status and comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression, through several patients’ reported outcomes. Scales and questionnaires will be analyzed and reported within the final analysis.

The intent of this first interim analysis was limited to preliminarily describing the effectiveness of cenobamate at the 12-week time point and did not investigate other outcomes that have clinical relevance in a real-world scenario. For instance, long-term data collection about ASMs concomitant to cenobamate could be used to evaluate the switching strategy or the tapering procedures. Also, it would be possible to analyze how many patients showed no changes or an increase in seizure frequency. Finally, data about ADRs could be related to cenobamate dosage, to evaluate possible dosage-related AEs. The above-mentioned analyses are not part of the study’s statistical analysis plan; however, post hoc analyses could be added to the final analysis.

Conclusion

This preliminary analysis of the BLESS Study evaluated cenobamate in addition to other concomitant ASMs in an adult population treated according to clinical practice, and the findings confirmed a robust anti-seizure activity after 12 weeks of treatment. Although the included PwE came from many previous treatment failures, up to 15.0% of them were seizure-free at 12 weeks after starting cenobamate, and no new safety events were reported. While awaiting the results of the next preplanned interim and final analyses of the BLESS Study comprehensive of all primary, secondary, and explorative long-term outcomes, these preliminary results contribute to evidence about cenobamate real-world effectiveness.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ioannou P, Foster DL, Sander JW, et al. The burden of epilepsy and unmet need in people with focal seizures. Brain Behav. 2022;12(9): e2589.

Elizebath R, Zhang E, Coe P, Gutierrez EG, Yang J, Krauss GL, Epilepsy Behav. Cenobamate treatment of focal-onset seizures: Quality of life and outcome during up to eight years of treatment. 2021;116:107796

Asadi-Pooya AA, Brigo F, Lattanzi S, Blumcke I. Adult epilepsy. Lancet. 2023;402:412–24.

Chen Z, Brodie MJ, Liew D, Kwan P. Treatment outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy treated with established and new antiepileptic drugs: a 30-year longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:279–86.

ONTOZRY® Summary of Product Characteristics_last update on January 2024

Krauss GL, Klein P, Brandt C, et al. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive cenobamate (YKP3089) in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures: a multicentre, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response trial. Lancet Neurol. 2019;19:38–48.

Chung SS, French JA, Kowalski J, et al. Randomised phase 2 study of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures. Neurology. 2020;94:e2311–22.

French JA, Chung SS, Krauss GL, et al. Long-term safety of adjunctive cenobamate in patients with uncontrolled focal seizures: open-label extension of a randomized clinical study. Epilepsia. 2021;62(9):2142–50.

Klein P, Ferrari L, Rosenfeld WE. Cenobamate for the treatment of focal seizures. US Neurol. 2020;16(2):87–97.

Sperling MR, Abou-Khalil B, Aboumatar S, et al. Efficacy of cenobamate for uncontrolled focal seizures: post hoc analysis of a Phase 3, multicenter, open-label study. Epilepsia. 2021;62(12):3005–15.

Epstein M on behalf of ISPE. Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(8):589–95.

Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51(6):1069–77.

Villanueva V, Santos-Carrasco D, Cabezudo-Garcìa P et al., Real-world safety and effectiveness of cenobamate in patients with focal onset seizures: Outcomes from an Expanded Access Program. Epilepsia Open. 2023;00:1–12.

Beltrán-Corbellini A, Romeral-Jimenéz M, Mayo P, et al. Cenobamate in patients with highly refractory focal epilepsy: a retrospective real-world study. Seizure: Eur J Epilepsy. 2023;111:71–7.

Makridis KL, Kaindl AM. Real-world experience with cenobamate: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Seizure Eur J Epilepsy. 2023;112:1–10.

Connor GS, Williamson A. Effectiveness and safety of adjunctive cenobamate for focal seizures in adults with developmental disability treated in clinical practice. Epilepsy Behav Rep. 2022;18: 100533.

Peña-Ceballos J, Moloney P, Munteanu T, et al. Adjunctive cenobamate in highly active and ultra-refractory focal epilepsy: a “real-world” retrospective study. Epilepsia. 2023;00:1–11.

Pietrafusa N, Falcicchio G, Russo E, et al. Cenobamate as add-on therapy for drug resistant epilepsies: effectiveness, drug to drug interactions and neuropsychological impact. What have we learned from real word evidence? Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1239152.

Steinhoff BJ, Rosenfeld WE, Serratosa JM, et al. Practical guidance for the management of adults receiving adjunctive cenobamate for the treatment of focal epilepsy-expert opinion. Epilepsy Behav. 2021;123: 108270.

Smith MC, Klein P, Krauss GL, et al. Dose adjustment of concomitant antiseizure medications during cenobamate treatment: expert opinion consensus recommendations. Neurol Ther. 2022;11:1705–20.

Specchio N, Pietrafusa N, Vigevano F. Is cenobamate the breakthrough we have been wishing for? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9339.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all subjects participating in this study. The full list of BLESS Study members and investigators are provided in the supplementary material (see Supplementary 1).

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medineos SRL – a company subject to the direction and coordination of IQVIA Ltd. contributed to the conduction, scientific support, clinical operations, data management, and statistical analysis of the study, with medical writing and editorial assistance provided by Daniela Longo, PhD, of PopMED. Angelini Pharma S.p.A. funded the medical writing and editorial assistance. This manuscript was prepared according to the International Society for Medical Publication Professionals’ “Good Publication Practice for Communicating Company-Sponsored Medical Research: GPP3”. MedDRA® trademark is registered by ICH.

Funding

The BLESS Study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Angelini Pharma S.p.A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated to the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. Michela Procaccini, Nathalie Falsetto, Valentina Villano, Gabriele Camattari, Alessandra Ori, Simona Lattanzi and Giancarlo Di Gennaro conceptualized the design of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and carried out data interpretation. Federica Ranzato, Carlo Di Bonaventura, Paolo Bonanni, Antonio Gambardella, Elena Tartara, Giovanni Assenza and Giancarlo Di Gennaro were responsible for the patient enrollment and the collection of clinical data, and carried out data interpretation. Simona Lattanzi, Giancarlo Di Gennaro, Valentina Villano, Gabriele Camattari, and Alessandra Ori revised the manuscript and provided substantial comments. The BLESS Study Group participated in the collection of study data (see Supplementary 1).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Simona Lattanzi has received speaker or consultancy fees from Angelini Pharma, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Medscape and UCB Pharma and has served on advisory boards for Angelini Pharma, Arvelle Therapeutics, BIAL, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals and Rapport Therapeutics. Federica Ranzato has received speaker fees from Angelini Pharma, Eisai, UCB, and LivaNova and has participated in advisory board for Angelini Pharma. Carlo Di Bonaventura has received consulting fees and honoraria from UCB Pharma, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Bial, Angelini Pharma, Lusofarmaco, and Ecupharma. Paolo Bonanni has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from EISAI, Angelini, Jazz and Livanova and has served on advisory boards for BIAL, Eisai, Proveca outside the submitted work. Antonio Gambardella and Giovanni Assenza declare no conflict of interest. Elena Tartara has received speaker fees from Eisai and advisory board fees from Angelini. Michela Procaccini is an employee of Angelini Pharma, Italy. Nathalie Falsetto is an employee of Angelini Pharma, Italy. Valentina Villano is an employee of Angelini Pharma, Italy. Gabriele Camattari is an employee of Angelini Pharma, Italy. Alessandra Ori is an employee of IQVIA-Medineos. Giancarlo Di Gennaro has received speaker honoraria from EISAI, UCB-Pharma, Livanova, Lusofarmaco, GW Pharmaceuticals. Served on advisory boards for Bial, Arvelle Therapeutics, Angelini Pharma, UCB-Pharma.

Ethical Approval

All participants received a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures and goals, consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964 and its later amendments), and voluntarily participated in this study after signing a written informed consent form. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating institutions before the start of data collection (first approval of the Coordinating Ethics Committee—Comitato Etico IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Mediterraneo Neuromed—on September 29, 2022; see Supplementary 3—Table S2), and conducted under the guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) (Epstein, 2005) and applicable regulatory requirements.

Additional information

The members of the BLESS Study Group are listed in Supplementary 1.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lattanzi, S., Ranzato, F., Di Bonaventura, C. et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Adjunctive Cenobamate in People with Focal-Onset Epilepsy: Evidence from the First Interim Analysis of the BLESS Study. Neurol Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00634-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-024-00634-5