Abstract

Rosellinia necatrix is an ascomycete that causes white root rot (WRR) of several plant host species resulting in economic losses to affected agricultural and forestry industries in various regions. This study aimed to identify and monitor the prevalence of R. necatrix in avocado orchards in South Africa. We used both morphological and molecular methods to isolate and identify R. necatrix from diseased plant material and soil. Results showed that R. necatrix was present on avocado in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. Additionally, a semi-selective medium, containing Rose Bengal, nystatin, cycloheximide, chlorothalonil and 2-phenylphenol, was developed to improve isolation of R. necatrix. We also tested an already established R. necatrix-specific TaqMan qPCR protocol to determine if it can reliably detect the pathogen isolates in planta in the South African samples. Based on our results the technique had a detection rate of 91.3% in artificially infected roots and 100% in artificially inoculated soil. We tested natural infected plant and soil samples and detected R. necatrix in 86% of the plant samples and in 70% of the soil samples. Using a selective medium or an in planta molecular detection method streamlines isolation and detection of R. necatrix, which will help prevent further spread of the pathogen. Moreover, additional information on the prevalence of WRR will create awareness among growers and provide a basis for management of the disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The avocado (Persea americana Mill.) industry is economically important in South Africa, with approximately 14,700 ha under avocado production, which totals approximately 125,000 t of fruit, of which, approximately 55% is exported (Donkin, 2021). Production mainly occurs in the Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces (Donkin, 2021). An increase in existing and emerging diseases of avocado in South Africa could cause devastation of commercial orchards with some new pathogens likely spreading to other hosts (Farr et al., 2021; Sztejnberg & Madar, 1980).

Rosellinia necatrix Berl. ex Prill. (anamorph: Dematophora necatrix Hartig) is an ascomycete in the family Xylariaceae that has become a problematic pathogen in tropical, subtropical and temperate regions (Pliego et al., 2012). The fungus causes white root rot (WRR) on many important crops including avocado, with mycelia invading the roots and crown of hosts (Pliego et al., 2009). Wilt ensues, and sudden death of colonized host plants occurs due to the collapse of the conducting vessels and toxin migration into the plant (Arjona-Girona et al., 2017; Pliego et al., 2009). WRR diagnosis is difficult since aerial symptoms are unreliable and non-specific (Pérez-Jiménez, 2006; ten Hoopen & Krauss, 2006).

The necrotrophic lifestyle of R. necatrix allows the pathogen to survive as a saprophyte on woody debris and organic matter in the soil (Pasini et al., 2016; Pérez-Jiménez, 2006). Consequently, once an area is infested, it is very difficult to control the disease (Arjona-López et al., 2020; Pliego et al., 2012). The pathogen is widespread, with multiple reports on fruit trees, fruit crops, field crops, nut trees and woody plants in many regions (Farr et al., 2021). Agriculturally important hosts of R. necatrix include apple, pear, plum, citrus, mango, coffee, olive, grapevines, and avocado. A few lesser known, economically important hosts include macadamia, pine, potato and cotton (Pliego et al., 2012; Sztejnberg & Madar, 1980). Many of the susceptible crops are grown in South Africa and are grown in the same areas as avocado. Currently, there is no commercial avocado rootstock available that has been proven to be tolerant or resistant to WRR. However, a breeding program in Spain has reported some tolerant rootstock candidates which are under evaluation (Barceló-Muñoz et al., 2007).

The emergence of WRR on avocado in Spain and Israel has caused devastation in commercial orchards (López-Herrera & Zea-Bonilla, 2007; Sztejnberg et al., 1983). The pathogen has been confirmed in pear and apple orchards, and on grapevine in South Africa (Marais, 1980; Van der Merwe & Matthee, 1974). In 2016 WRR was confirmed in avocado orchards in South Africa (van den Berg et al., 2018). Phytophthora root rot, caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands, is one of the most significant limiting factors of avocado production worldwide (Pérez-Jiménez, 2008). Therefore, a major concern is that the avocado industry in South Africa is reliant on P. cinnamomi resistant rootstocks, which are reported to be susceptible to R. necatrix (Pérez-Jiménez, 2008). Consequently, South African growers are not prepared for dealing with the threat. Symptoms of WRR in avocado have been mistaken for Phytophthora root rot or Armillaria root rot, thus R. necatrix may have been present on avocado in South Africa long before being reported in 2016 (ten Hoopen & Krauss, 2006; van den Berg et al., 2018). The rate of spread of R. necatrix in different orchards varies, with some orchards having rapidly develo** diseased and dying trees and others having only one or two affected trees (Carlucci et al., 2013; Pérez-Jiménez, 2006). The pathogen spreads to adjacent hosts in the infested orchard, with trees in close proximity to each other dying consecutively (Schena et al., 2008; Shiragane et al., 2019). Therefore, rapid and accurate detection of the pathogen is of great importance to slow spread (Arjona-López et al., 2019).

There are multiple techniques for confirmation of WRR. Conventional detection of R. necatrix involves isolation of the fungus from diseased tissue or baiting the soil with twigs or leaves (Eguchi et al., 2009; Pal & Sharma, 2019). But isolation is time-consuming and has low sensitivity, although valuable for the recovery of, and further studies on isolates (Castro et al., 2013; Pasini et al., 2016). To our knowledge, there is no selective medium for the recovery of R. necatrix isolates specifically from diseased plant material, which may aid in increasing the efficiency of the isolation process (Pasini et al., 2016; Pliego et al., 2012).

Molecular techniques are now commonly used for the rapid and accurate detection of plant pathogens (Ruano-Rosa et al., 2007; Schena et al., 2002). The most promising molecular detection methods for R. necatrix are PCR-based. Schena et al. (2002) designed a number of species-specific primers for the detection of R. necatrix using the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions of the rRNA genes. Shishido et al. (2012) developed a protocol for the detection of R. necatrix using TaqMan probes based on four of the primers designed by Schena et al. (2002), increasing specificity of the reaction. The value and importance of the PCR-based techniques to identify R. necatrix for validation of WRR diagnosis is evidenced by their increased use in different regions (Arjona-López et al., 2019; Ruano-Rosa et al., 2007; Takemoto et al., 2012).

The aim of this study was to firstly monitor the distribution and prevalence of R. necatrix in South African avocado orchards through diagnosis of infected trees, secondly to develop a semi-selective medium for isolation of R. necatrix from diseased tissue, and thirdly, to test the TaqMan qPCR method to identify R. necatrix in South African avocado orchards.

Materials and methods

Sample screening and fungal isolation

Diseased roots and bark (from the crown and lower trunk, respectively) were collected or received from multiple commercial South African avocado orchards in Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal from 2017 to 2021. Small sections of diseased plant tissue were excised (approximately 1 × 1 cm), surface sterilized in 1.5% NaHClO solution, rinsed in sterile distilled water, dried in a laminar flow hood and placed in Petri dishes on ½ strength potato dextrose agar (PDA, 19 g PDA (Biolab, Merck Laboratories, South Africa), 10 g agar and distilled water to a volume of 1 L). The Petri dishes were incubated in the dark at 25 °C for 4 to 7 days. Single hyphae from the white mycelial growth that typically resemble R. necatrix (characterised by pear-shaped swellings adjacent to the septa) were transferred onto fresh ½ strength PDA to obtain pure cultures. Cultures were deposited in the culture collection (CMW) at the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI, University of Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa).

Additional Rosellinia isolates were obtained either from collaborators, the CMW fungal culture collection or the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute culture collection (Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures [CBS], Utrecht, Netherlands). Fourteen isolates were provided by collaborators in South Africa and nine isolates were provided by other foreign collaborators or from the CBS culture collection. In total, 60 R. necatrix isolates and 3 isolates of other Rosellinia spp. were used in this study (Table 1).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing of fungal isolates

DNA was extracted from all isolates using PrepMan™ Ultra solution (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) as described by Duong et al. (2012). The DNA of each isolate was amplified using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region specific primers, ITS 1-F and ITS 4 (White et al., 1990), and actin gene primers, ACT-512F and ACT-783R (Carbone & Kohn, 1999). PCR reactions consisted of 20 to 50 ng template DNA, 1 U FastStart™ Taq DNA Polymerase (Roche Applied Science, USA), 2.5 μl 10x PCR reaction buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM of each dNTP, 0.2 μM of forward and reverse primer, and sterile nuclease-free water to a total volume of 25 μl. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel using a Gel Doc™ EZ Imager UV transilluminator (Bio-Rad, Gauteng, South Africa). PCR products were treated with EXO-SAP solution and sequencing PCR reactions were performed using BigDye v3.1 (Applied Biosystems®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania) according to the manual. Sequencing products were precipitated and submitted for analysis on an Applied Biosystems® 3500xL genetic analyzer (ABI3500xL) (Thermo Fisher Scientific®, Carlsbad, USA) at the DNA Sanger Sequencing facility, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa. Forward and reverse sequences were trimmed, and consensus sequences were constructed using BioEdit Sequence Alignment Editor version 7.0.5.3 (Hall, 1999) and subjected to a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) analysis (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] GenBank, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA) to confirm the identity of the putative R. necatrix isolates.

For phylogenetic analysis of the South African isolates of R. necatrix, generated sequence data was complemented with available sequence data for the ITS and actin gene regions from other Rosellinia spp. obtained from the NCBI GenBank database. The sequences of Hypoxylon intermedium (Achwein.) Y.M. Ju & J.D. Rogers (Sánchez-Ballesteros et al., 2000) and Hypoxylon ferrugineum G.H. Otth, both members of the Xylariales, were used as outgroup taxa (Castro et al., 2013). Datasets for each of the gene regions were aligned using the alignment program MAFFT version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) with the “gap opening penalty” set to default at 1.53. Alignments were trimmed and phylogenetic analyses were performed using MEGA version 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the Maximum likelihood (ML) method with the General Time Reversible Substitution model (nucleotide substitution, all sites and codon positions used) (Nei & Kumar, 2000) and the ML heuristic tree inference option with 1000 bootstrap replications. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained by applying the Neighbor-Joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value (very strong branch swap filter, 1 thread).

Development of a selective medium for R. necatrix

Individual and combinations of selective chemicals (Sigma Aldrich, Gauteng, South Africa) were screened using different R. necatrix isolates to ensure minimum inhibition of the target fungal pathogen. Chemicals tested for their efficacy for selection and their concentrations were: Rose Bengal (5, 20, 60, 80 μg active ingredient [a.i]./ml), nystatin (5, 20, 40, 60 μg a.i./ml), cycloheximide (2, 4, 5, 20 μg a.i./ml), chlorothalonil (2, 4, 5, 20 μg a.i./ml) and 2-phenylphenol (2, 4, 5, 20 μg a.i./ml). After sterilization in an autoclave for 20 min and cooling to 50 °C, ½ strength PDA was amended with appropriate volumes of each stock solution. The unamended ½ strength PDA medium was used as the control. The amended media were agitated for 2 min to allow for even mixing of the chemicals before pouring. Five isolates of R. necatrix (indicated in Table 1) were used to test for the sensitivity against the chemicals. The isolates were chosen based on their different growth rates (data not shown), and the different geographic regions and hosts from which they were recovered. An 8 mm agar plug was removed from the edge of actively growing R. necatrix colonies on ½ strength PDA and was transferred to the centre of each Petri dish containing the respective chemicals (10 replicate Petri dishes per treatment for each isolate, and two unamended control Petri dishes for each isolate). The colony diameter on each Petri dish was recorded as the mean of two perpendicular measurements after 168 hr of incubation at 25 °C in the dark, and the mean value of the 10 dishes was recorded. Unpaired t tests (α = 0.05) were conducted on the means for each isolate to determine any significant differences using GraphPad Prism version 5 (San Diego, CA, USA) (Motulsky, 2007).

The five chemicals were evaluated for their combined effect on the growth of five isolates of R. necatrix. Different combinations of chemicals (SM1 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 40 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 2 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 2 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 2 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol), SM2 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 20 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 2 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 1 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 2 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol) and SM3 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 20 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 1 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 1 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 1 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol)) were incorporated into ½ strength PDA as described above. Growth tests were subsequently conducted as previously described, with the unamended medium serving as the control. Analysis of the data was as described for the individual chemicals.

After demonstrating that the growth of most of the R. necatrix isolates was not inhibited by more than 50% on two of the three selective media combinations (SM2 and SM3), they were assessed using artificially and naturally infected plant material. Naturally infected avocado root samples were excised (approximately 1 × 1 cm), surface sterilized using 1.5% NaHClO solution for 3 min, washed using sterile distilled water and dried in a laminar flow hood. The samples were evenly divided among 10 dishes containing two different selective medium combinations and unamended ½ strength PDA dishes. Dishes were incubated at 25 °C for 14 days in the dark and evaluated for the presence of R. necatrix by transferring mycelia from the peripheral portion of develo** fungal colonies to 65 mm culture dishes containing ½ strength PDA. The percentage recovery of R. necatrix from the selective media and ½ strength PDA dishes was determined. The identity of the recovered R. necatrix isolates was confirmed by PCR using the species-specific primers R3-R8 (Schena et al., 2002). Branches on two-year-old avocado plantlets were wounded with a cork borer and inoculated with mycelial plugs from 2-week-old R. necatrix cultures and wrapped with parafilm. The plantlets were maintained under greenhouse conditions for 6 weeks (daily mean maximum temperature of 27.9 °C, and a mean minimum temperature of 14.4 °C, an average of 13 hr of daylight per day, watered by application of 20 l/h for 30 min twice a day at an interval of 12 h, and fertilised with Nitrosol (50 ml/5 l of water; Pest and Chemical Supply, Gauteng, South Africa) applied at 50 ml per plant every 14 days) (Magagula et al., 2021). The artificially and naturally infected avocado plant samples were used to compare the recovery rate from the better performing selective medium from the first trial described above (SM3) to that of ½ strength PDA and acidified PDA (APDA) (PDA amended with 0.2% lactic acid, pH 3.5–4) (Arjona-López et al., 2019; ten Hoopen & Krauss, 2006). Bark samples excised (approximately 1 × 1 cm) 6 weeks after inoculation from the branch lesions on the plantlets, or from roots of naturally diseased trees, were superficially sterilized using 1.5% NaHClO solution for 3 min, washed with sterile distilled water and dried in a laminar flow hood, and evenly divided among 30 Petri dishes containing SM3, 30 dishes containing ½ strength PDA and 30 dishes containing APDA.

Molecular detection in artificially inoculated plant material and soil

Chopstick inoculum of R. necatrix was prepared using a modification of the protocol described by Negishi et al. (2011), as reported in Magagula et al. (2021). Briefly, South African isolates of R. necatrix were transferred to PDA in Petri dishes and incubated at 25 °C in the dark. Wooden chopsticks (approximately 5 mm in diameter) were cut into 2 cm sections, washed and soaked in distilled water for 2 days. The sticks were autoclaved at 120 °C for 15 min twice and dried at 65 °C for 2 days. Four sterile chopsticks were placed on the growing mycelia of each dish and incubated at 25 °C in the dark until mycelia covered the stick sections completely.

One-year-old avocado plantlets of different rootstocks (Dusa®, R0.12 and R0.06) were transferred to a sterile soil-perlite mixture and grown under greenhouse conditions as previously described (Magagula et al., 2021). The plants were inoculated by placing a colonized chopstick section in each of the four holes prepared using a cork borer (10 mm in diameter) 2 cm from the root collar of each plant and 5 cm below the surface of the soil-perlite mixture, and subsequently covered with the soil-perlite mixture. Control plants received sterile chopstick sections. At 42- and 70-days post inoculation (dpi), when plantlets showed evidence of canopy decline, the roots were sampled, washed, and ground with liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle. Approximately 50 ml of soil samples were collected from four points around each of the plantlets from the upper 5 to 10 cm of surface soil of the rhizosphere. The soil samples were pooled and mixed. The soil was dried at 25 °C for 2 days, mixed again, sieved and ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. Roots and soil from control plants were used as negative controls.

DNA was extracted from the ground plant material (10–30 mg) using a modified CTAB (cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) extraction method described by Brunner et al. (2001). DNA was extracted from the soil samples (450–500 mg) using the NucleoSpin® Soil kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany). The concentration of each DNA sample was determined using a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA), and visualized for quality and quantity on a 1.5% agarose gel under UV.

The species-specific primer pair R7/R10 was selected for detection of R. necatrix in the samples (Schena et al., 2002). R7/R10 are short enough to be used in qPCR, with a TaqMan probe (TR10–7) (Schena et al., 2002; Shishido et al., 2012). The protocol for detection was as described by Shishido et al. (2012) with a few modifications. The TR10–7 probe was labeled at the 5′ terminus with the fluorochrome 6-FAM, internally with the quencher ZEN™, and at the 3′ terminus with the quencher Iowa Black® FQ (IDT, Whitehead Scientific, Cape Town, South Africa). For each DNA sample, reactions were run in triplicate. The reaction volume was 20 μl comprising 5 μl of template DNA, 10 μl of TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK), 900 nM of forward and reverse primers, and 250 nM of the TR10–7 probe, respectively. Amplifications and fluorescence detection were conducted using a CFX Connect™ Real-Time System (Bio-Rad, Singapore). Each set of reactions included a non-template control (negative control) to verify that no contamination was present in the reagents.

Molecular detection in naturally infected plant material and soil

Diseased samples were collected from the roots and crown of 60 naturally diseased trees and primary isolation of R. necatrix from the samples was performed using the SM3 selective media described above. Only 42 samples suspected to be infected with R. necatrix (symptomatic and non-symptomatic) were used to evaluate the detection techniques. DNA was extracted from the plant material using the CTAB method, checked for quality and quantity on a 1.5% agarose gel and screened for presence of R. necatrix using the TaqMan qPCR as previously described. A map showing the sample sites confirmed to have R. necatrix was compiled using Google Maps (https://www.google.com/maps/search/).

Soil samples were collected from three infested avocado orchard blocks in Mozambique. Approximately 100 g of soil from the upper 5 to 10 cm of soil was collected from two points approximately 10 cm from the trunk of four different trees in the middle of the orchards and from four different trees on the outer boundaries of the orchards. Avocado bait twigs were used to indicate the presence of R. necatrix in the soil samples (Eguchi et al., 2009). Avocado twigs (approximately 4 cm long and 1.5 cm in diameter) were placed at five points in the soil samples and incubated for 2 weeks at room temperature in the dark. Twigs were ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and DNA was extracted using the CTAB method and screened for the presence of R. necatrix using the TaqMan qPCR as previously described. Only those soil samples where the presence of R. necatrix was confirmed with baiting were used for molecular detection. The positive samples were pooled and mixed as composite samples to represent an orchard. The soil was dried, mixed, sieved and ground into a fine powder as previously described. DNA was extracted from the soil samples (450 to 500 mg) using the NucleoSpin® Soil kit, checked for quality and quantity on a 1.5% agarose gel and screened for presence of R. necatrix using the TaqMan qPCR previously described.

Results

Assessment of the spread and prevalence of R. necatrix

Over 470 diseased bark, root and soil/media samples from approximately 57 avocado orchard plots and 3 nurseries in South Africa and surrounding countries were collected or received for disease screening for WRR between 2017 and 2021 (on average 2 to 6 samples per orchard plot). Thirty-seven R. necatrix isolates were obtained from either different trees in the same orchard or different orchards in South Africa. ITS and actin sequence BLAST analysis of all sample isolates of putative R. necatrix revealed 97–100% nucleotide homology to known R. necatrix sequences. A total of 83 of the sequences were deposited in GenBank (MT341816-MT341823, MT341825-MT341854; MT671572-MT671613; MT741534-MT741536). WRR was detected in three of the four avocado growing regions in South Africa, namely Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal. A total of 32 orchard plots were determined to be infested (22 in Limpopo, 9 in Mpumalanga and 1 in KwaZulu-Natal) (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic analysis of R. necatrix isolates

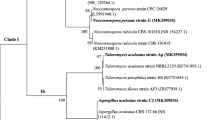

PCR amplification of the ITS and actin regions of 45 isolates of putative Rosellinia spp. yielded fragments of ~570 bp and ~ 290 bp in length, respectively, as expected for R. necatrix. The ITS sequence analysis included a total of 74 nucleotide sequences (of these, 24 Rosellinia species sequences were obtained from GenBank) with a total of 691 bp in the final amplicon dataset (Fig. 2). The actin sequence analysis included a total of 21 nucleotide sequences (of these 11 Rosellinia species sequences were obtained from GenBank) with a total of 300 bp in the final amplicon dataset (Fig. 3). Based on DNA sequence analyses of the two gene regions, the 60 isolates all belong in the clade containing the isolates of R. necatrix, including CBS isolates 267.30 and 349.36, which confirmed their identity as R. necatrix. This was supported by bootstrap values of >93%. Only a subset of the isolates is shown in both trees as representative sequences.

Phylogenetic tree inferred using the Maximum Likelihood analysis of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences for Rosellinia species, based on the General Time Reversible model. Bootstrap support values are indicated at the nodes. Bars indicate the number of substitutions per position. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. ITS sequences of all R. necatrix isolates were identical and therefore only a few representative isolate sequences were used in the figure. The representative R. necatrix isolate sequences labeled with the ARP personal culture collection number are highlighted by red blocks. The remaining sequences are labelled with their GenBank accession numbers

Phylogenetic tree inferred using the Maximum Likelihood analysis of actin sequences for Rosellinia species, based on the General Time Reversible model. Bootstrap support values are indicated at the nodes. Bars indicate the number of substitutions per position. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to nodes. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Actin sequences of all R. necatrix isolates were identical and therefore only a few representative isolate sequences were included. The representative R. necatrix isolate sequences labeled with the ARP personal culture collection number are highlighted by red blocks. The remaining sequences are labelled with their GenBank accession numbers

Development of a selective medium for R. necatrix

Five chemicals were used to test their inhibitory activity towards R. necatrix. The sensitivity of common fungal saprophytes to the chemicals screened has been determined in previous studies (Tsao, 1970; Vaartaja, 1968), however their inhibitory effect on R. necatrix has not been determined. We present the concentration of each chemical that inhibited the growth of R. necatrix by <50% after 168 hr. incubation (Fig. 4a-e).

Mycelial growth (mm) of five different isolates of Rosellinia necatrix after 4 days on ½ strength potato dextrose agar (PDA) amended with a combination of different concentrations of each selective chemical compared to control Petri dishes after incubation at 25 °C in the dark. Each bar indicates the mean and standard error of mycelial growth of 10 replicates of each isolate including significant differences (p < 0.05) between the amended and control dishes, indicated by asterisks (*). (a) 40 μg a.i./ml of nystatin. (b) 2 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide. (c) 2 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil. (d) 2 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol. (e) 80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal. (f) SM1 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 40 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 2 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 2 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 2 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol). (g): SM2 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 20 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 2 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 1 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 2 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol). (h) SM3 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 20 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 1 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 1 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 1 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol)

The first selective medium (SM1) combination inhibited the growth of all R. necatrix isolates by >50% (Fig. 4f). Thus, the concentrations of nystatin and chlorothalonil were lowered to 20 μg a.i./ml and 1 μg a.i./ml in the subsequent trial (SM2). The altered concentrations when used in combination inhibited the growth of one of the R. necatrix isolates (T4KF) by >50% (Fig. 4g). Finally, the concentrations of cycloheximide and 2-phenylphenol were lowered to 1 μg a.i./ml and 1 μg a.i./ml, allowing the final selective medium (SM3) to inhibit the growth of all R. necatrix isolates by <50% (Fig. 4h).

The second (SM2) and third (SM3) selective media combinations were tested for their efficacy in suppressing the growth of general saprophytes present when isolating R. necatrix from diseased samples, compared to ½ strength PDA. SM3 exhibited a recovery rate for R. necatrix of 95%, SM2 a recovery rate of 60%, while the basal medium allowed a recovery rate of just 30%. The isolation efficacy of SM3 was compared with APDA. In the first trial, SM3 allowed for a recovery rate of 70%, while APDA allowed a recovery rate of 40%. In the consecutive trials, SM3 allowed for an average recovery rate of 77%, while APDA allowed for an average recovery rate of 47%. Therefore, SM3 allowed for improved recovery of R. necatrix with less contaminants overtaking the growth of the target pathogen (Fig. 5).

Microbial growth observed on the selective media (SM3) compared to the ½ strength potato dextrose agar (PDA, 19 g PDA, 10 g agar and distilled water to a volume of 1 L) and acidified PDA (APDA, PDA amended with 0.2% lactic acid, pH 3.5–4) Petri dishes were photographed 4 days after commencing incubation in the dark at 25 °C (arrows indicate Rosellinia necatrix growth)

Detection in artificially and naturally infected plant and soil samples

The efficiency of the molecular detection methods can differ depending on the fungal strain and laboratory protocols. Takemoto et al. (2009) found that R. necatrix isolate W536 yielded no product in a conventional PCR using the species-specific primer pair R3-R8. However, results from our study revealed that the R7/R10 primers from Schena et al. (2002) were able to detect all of the R. necatrix isolates tested, highlighting the use of the protocol for the rapid identification of R. necatrix from field samples.

Inoculated avocado plantlets exhibited symptoms of damaged and dead roots, wilting of the leaves, chlorosis, leaf drop, death of branches and drying of the plant (Fig. 6). White mycelial growth was observed on the roots and in the soil around plantlets. The TaqMan qPCR detected R. necatrix in 21 of 23 artificially inoculated avocado root samples and 20 of 20 artificially inoculated soil samples.

Symptoms of white root rot in one-year-old avocado plantlets artificially inoculated with Rosellinia necatrix. a Aerial symptoms of white root rot observed at 4 weeks post inoculation (wpi) with R. necatrix. b Hyphal strands and cords of R. necatrix on the surface of the damaged avocado roots at 6 wpi. c White mycelia of R. necatrix in the soil around the plantlet at 6 wpi. d A pure culture of R. necatrix isolated from inoculated plantlet roots on ½ strength potato dextrose agar

Symptoms of WRR observed in the field included retardation of tree growth, droo** and wilting of the leaves, chlorosis and general dieback of the tree. Signs of the pathogen included cottony white mycelia growth underneath and/or on the surface of the bark at the crown of the tree, in the soil and on organic debris, and on the infected roots, as described previously in van den Berg et al. (2018). Many trees died suddenly, sometimes with leaves and fruit still attached to branches. The TaqMan qPCR detected the presence of R. necatrix in 36 of 42 diseased plant samples and 14 of 20 soil samples collected from South African avocado orchards. However, positive isolations were obtained from just 29 of the 42 plant samples and none of the soil samples.

Discussion

WRR caused by R. necatrix was observed in a commercial avocado orchard in 2016 in Limpopo province, South Africa. Spread between orchards could have occurred through several pathways (Pasini et al., 2016). One of the most probable means is through contamination of farm equipment with soil containing fungal spores (López-Herrera & Zea-Bonilla, 2007; Pasini et al., 2016). Another possible route could be from nurseries which distribute infected plants; however, nursery screening in this study was minimal and should be investigated further as a source of disease spread (Pérez-Jiménez, 2006). Nevertheless, once the pathogen has become established, eradication and control has proven extremely difficult (Pliego et al., 2012).

It is evident that R. necatrix is present in numerous orchards throughout Limpopo and Mpumalanga in South Africa. The widespread nature of the pathogen could indicate a lack of awareness of WRR in South Africa, as well as the unspecific symptoms associated with the disease, leading to misdiagnosis by farmers and consultants. Consequently, the pathogen has spread extensively throughout the two most prominent avocado growing regions (Donkin, 2021). Previous studies in South Africa focused on Rosellinia root rot of apple and pear trees (Van der Merwe & Matthee, 1974). Symptoms on avocado and molecular characterization of R. necatrix in our study are consistent with previous reports of WRR (Pliego et al., 2012). Phylogenetic analyses of gene sequences placed all isolates considered in this study in the same clade as R. necatrix, with bootstrap values of >90% (Ju et al., 2007; Vu et al., 2019). Therefore, our study confirmed that R. necatrix is present in at least three provinces in South Africa, with infection of avocado being most severe in Limpopo province. Infection of avocado was also widespread in Mpumalanga province. However, our surveillance study was based on correspondance with growers and consultants for sampling of diseased areas. Thus, WRR may be more prominent than we have reported.

Isolation of pathogenic species from environmental samples is a crucial part of many research studies focused on disease diagnosis, taxonomy, and genetics (Kanematsu et al., 1997; Pasini et al., 2016). Therefore, we developed a semi-selective medium for R. necatrix. Previous studies on selective media for isolation of Rosellinia species focused on R. pepo and R. bunodes from cocoa, coffee and potato (Kulshrestha et al., 2014; ten Hoopen & Krauss, 2006). The past studies found that Rose Bengal and acidified PDA were useful in isolation of Rosellinia species, however, a suitable selective medium for isolation of R. necatrix was not available (Pliego et al., 2012; ten Hoopen & Krauss, 2006). SM3 (80 μg a.i./ml of Rose Bengal, 20 μg a.i./ml of nystatin, 1 μg a.i./ml of cycloheximide, 1 μg a.i./ml of chlorothalonil and 1 μg a.i./ml of 2-phenylphenol) allowed for efficient recovery of R. necatrix within 5–7 days with an increase in recovery rate compared to non-amended media or APDA. SM3 improves primary isolation of the pathogen from diseased samples with less contamination. Thus, SM3 medium will be useful for the isolation of R. necatrix from various environmental samples. Although molecular detection tools are the obvious choice for rapid diagnosis and prevalence studies, recovery of the pathogen is critical for consecutive analyses involving pathogenicity, mutational, disease control, and pathogen population studies (Castro et al., 2013; Kanematsu et al., 1997; Magagula et al., 2021). Hence, the development of a selective medium for the isolation of important strains is an important result that we report.

We made use of a high-throughput TaqMan real-time PCR protocol to detect R. necatrix in plant and soil samples collected from avocado orchards in South Africa. Precedent studies reported improved sensitivity and efficiency of real-time PCR when compared to conventional PCR to detect R. necatrix using nucleotide sequences in the ITS regions (Arjona-López et al., 2019; Shishido et al., 2012). Schena et al. (2002) designed specific primers and modified them for use in a Scorpion-PCR. However, Scorpion probes have a complicated structure which makes them difficult and expensive to synthesize, as well as being susceptible to non-amplification related degradation of the probe during PCR cycles (Josefsen et al., 2009; Shishido et al., 2012). TaqMan qPCR was also proven to be more sensitive for detection of R. necatrix, with a detection limit of 1 fg/μl of DNA compared to the detection limit of Scorpion-PCR at 1 pg/μl of DNA. Thus, the TaqMan probe was chosen for detection of R. necatrix in plant and soil samples using real-time PCR (Arjona-López et al., 2019; Shishido et al., 2012). Although the primer pair R7/R10 was proven to be effective for R. necatrix isolates in the studies by Schena et al. (2002) and Shishido et al. (2012), the effectiveness of the R7/R10 primer combination, and others, need to be evaluated using South African strains before being implemented in pathogen prevalence studies.

Previous reports found that R. necatrix was only detectable in infested soil samples using nested qPCR and undetectable in one step amplification for most of the samples tested due to the miniscule amounts of target DNA recovered using common DNA extraction methods (Ruano-Rosa et al., 2007; Schena & Ippolito, 2003). However, nested PCR protocols increase the chances of false positives due to cross-contamination, increase time required for diagnosis and make quantitative analyses more challenging (Ippolito et al., 2004; Schena et al., 2013). Arjona-López et al. (2019) recently developed a duplex TaqMan qPCR with the inclusion of an internal positive control in order to rule out the presence of PCR inhibitors that may not have been removed during DNA extraction from soil samples. The method was reported to improve detection of R. necatrix from infested soil samples (Arjona-López et al., 2019). However, duplex PCR protocols increase the expense and complexity of diagnosis. Thus, we adopted the conventional, singleplex qPCR for R. necatrix detection with the use of a commercial kit for DNA extraction, which has allowed for improved quantity and quality of DNA extracted from soil in recent studies, including the present study (Arjona-López et al., 2019; Mahmoudi et al., 2011). Therefore, presence of inhibitors, such as humic compounds, in the final DNA solution was less likely, while improving the simplicity and rapidity of detection (Bridge & Spooner, 2001; Smith et al., 2005).

Primary isolation, culturing, morphological identification and sequencing can take at least 2 weeks to accomplish for R. necatrix, while the TaqMan qPCR reduced the time needed for diagnosis to 3 days. Thus, the method enabled rapid detection while yielding reliable results, with 91.3% detection accuracy in artificially infected roots and 100% accuracy in artificially inoculated soil. The efficiency of the results prompted us to confirm the viability of the method using naturally infected samples from the field, which resulted in a detection accuracy of 86% with naturally infected bark and root samples, and accuracy of 70% in naturally infested soil samples. Variability in detection could be attributed to the differences in pathogen load and efficiency of DNA extraction between plant samples from trees of different ages. Furthermore, a common problem could be the selection of sampling sites since the distribution of a pathogen is not homogeneous. The presence of inhibitors in the DNA solutions, such as polyphenols, tannins, polysaccharides and lignin can also lead to false negative results (Schena et al., 2013).

This is the first survey of the spread and prevalence of R. necatrix on avocado in South Africa, which may aid in awareness, treatment and future pathogen population and management studies. Our research also resulted in the development of a semi-selective medium that can be used for the isolation of R. necatrix. The combination of the chemicals allowed for improved recovery of R. necatrix from different diseased samples, which will be important for subsequent studies. Our results suggest that the specificity and relative simplicity of the TaqMan qPCR protocol designed by Shishido et al. (2012) is beneficial for rapidly diagnosing WRR, which is of utility for epidemiological studies. The semi-selective medium and the TaqMan qPCR protocol reduce the time and labour involved in detection and primary isolation, allowing greater efficiency in new studies on the pathogen.

Data Availability

The FABI fungal culture collection (CMW) culture numbers and NCBI GenBank accession numbers obtained for nucleotide sequences for each isolate in this study are provided in Table 1. Nucleotide sequences are given in Online Resource 1.

References

Arjona-Girona, I., Ariza-Fernández, T., & López-Herrera, C. J. (2017). Contribution of Rosellinia necatrix toxins to avocado white root rot. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 148, 1–9.

Arjona-López, J., Capote, N., Melero-Vara, J., & López-Herrera, C. (2020). Control of avocado white root rot by chemical treatments with fluazinam in avocado orchards. Crop Protection, 131, 105100.

Arjona-López, J. M., Capote, N., & López-Herrera, C. J. (2019). Improved real-time PCR protocol for the accurate detection and quantification of Rosellinia necatrix in avocado orchards. Plant and Soil, 443, 605–612.

Arjona-López, J. M., Telengech, P., Jamal, A., Hisano, S., Kondo, H., Yelin, M. D., Arjona-Girona, M. I., Kanematsu, S., López-Herrera, C., & Suzuki, N. (2018). Novel, diverse RNA viruses from Mediterranean isolates of the phytopathogenic fungus, Rosellinia necatrix: Insights into evolutionary biology of fungal viruses. Environmental Microbiology, 20, 1464–1483.

Barceló-Muñoz, A., Zea-Bonilla, T., Jurado-Valle, I., Imbroada-Solano, I., Vidoy-Mercado, I., Pliego-Alfaro, F., & López-Herrera, C. (2007). Programa de selección de portainjertos de aguacate tolerantes a la podredumbre blanca causada por Rosellinia necatrix en el sur de España. VI World Avocado Congress.

Bridge, P., & Spooner, B. (2001). Soil fungi: Diversity and detection. Plant and Soil, 232, 147–154.

Brunner, I., Brodbeck, S., Büchler, U., & Sperisen, C. (2001). Molecular identification of fine roots of trees from the Alps: Reliable and fast DNA extraction and PCR-RFLP analyses of plastid DNA. Molecular Ecology, 10, 2079–2087.

Carbone, I., & Kohn, L. M. (1999). A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia, 91, 553–556.

Carlucci, A., Manici, L. M., Colatruglio, L., Caputo, A., & Frisullo, S. (2013). Rosellinia necatrix attack according to soil features in the Mediterranean environment. Forest Pathology, 43, 12.

Castro, B. L., Carreño, A. J., Galeano, N. F., Roux, J., Wingfield, M. J., & Gaitán, Á. L. (2013). Identification and genetic diversity of Rosellinia spp. associated with root rot of coffee in Colombia. Australasian Plant Pathology, 42, 515–523.

Dafny-Yelin, M., Mairesse, O., Jehudith, M., Shlomit, D., & Malkinson, D. (2018). Genetic diversity and infection sources of Rosellinia necatrix in northern Israel. Phytopathologia Mediterranea, 57, 37–47.

Donkin, D. J. (2021, September 10) An overview of the South African avocado industry. The South African Avocado Growers’ Association, https://www.avocado.co.za/overview-south-african-avocado-industry/

Duong, T. A., De Beer, Z. W., Wingfield, B. D., & Wingfield, M. J. (2012). Phylogeny and taxonomy of species in the Grosmannia serpens complex. Mycologia, 104, 715–732.

Eguchi, N., Kondo, K. I., & Yamagishi, N. (2009). Bait twig method for soil detection of Rosellinia necatrix, causal agent of white root rot of Japanese pear and apple, at an early stage of tree infection. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 75, 325–330.

Farr, D. F., Rossman, A. Y., Palm, M. E. & McCray, E. B. (2021, September 10) Fungal Databases, Rosellinia necatrix. Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, http://nt.ars-grin.gov/fungaldatabases/

Fournier, J., Lechat, C., Courtecuisse, R. & Moreau, P. A. (2017) The genus Rosellinia (Xylariaceae) in Guadeloupe and Martinique (French West Indies). Ascomycete.org, 9, https://doi.org/10.25664/art-0212

Hall, T. A. (1999). BioEdit: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series, 41, 95–98.

Hamelin, R. C., Tanguay, P., & Uzunovic, A. A. (2013). Molecular detection assays of forest pathogens. Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources.

Ippolito, A., Schena, L., Nigro, F., Soletiligorio, V., & Yaseen, T. (2004). Real-time detection of Phytophthora nicotianae and P. citrophthorain citrus roots and soil. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 110, 833–843.

Josefsen, M. H., Löfström, C., Sommer, H. M., & Hoorfar, J. (2009). Diagnostic PCR: Comparative sensitivity of four probe chemistries. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 23, 201–203.

Ju, Y. M., Hsieh, H. M., Ho, M. C., Szu, D. H., & Fang, M. J. (2007). Theissenia rogersii sp. nov. and phylogenetic position of Theissenia. Mycologia, 99, 612–621.

Kanematsu, S., Hayashi, T., & Kudo, A. (1997). Isolation of Rosellinia necatrix mutants with impaired cytochalasin E production and its pathogenicity. Japanese Journal of Phytopathology, 63, 425–431.

Kulshrestha, S., Seth, C. A., Sharma, M., Sharma, A., Mahajan, R., & Chauhan, A. (2014). Biology and control of Rosellinia necatrix causing white root rot disease: A review. Journal of Pure and Applied Microbiology, 8, 1803–1814.

López-Herrera, C. J., & Zea-Bonilla, T. (2007). Effects of benomyl, carbendazim, fluazinam and thiophanate methyl on white root rot of avocado. Crop Protection, 26, 1186–1192.

Magagula, P., Taylor, N., Swart, V., & van den Berg, N. (2021). Efficacy of potential control agents against Rosellinia necatrix and their physiological impact on avocado. Plant Disease, 105, 3385–3396.

Mahmoudi, N., Slater, G. F., & Fulthorpe, R. R. (2011). Comparison of commercial DNA extraction kits for isolation and purification of bacterial and eukaryotic DNA from PAH-contaminated soils. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 57, 623–628.

Marais, P. G. (1980). Fungi associated with decline and death of nursery grapevines in the Western Cape. Phytophylactica, 12, 9–14.

Motulsky, H. (2007). Prism 5 statistics guide. GraphPad Software, 31, 39–42.

Negishi, H., Imai, T., Nakamura, H., Hirosuke, S., & Arimoto, Y. (2011). A simple and convenient inoculation method using small wooden chips made of disposable chopsticks for Rosellinia necatrix, the causal fungus of white root rot disease on fruit trees. Journal of ISSAAS (International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences), 17, 128–133.

Nei, M., & Kumar, S. (2000). Molecular evolution and phylogenetics. Oxford University Press.

Pal, J., & Sharma, S. K. (2019). Standardization of isolation methodology for early detection and estimation of major hot spots of Dematophora necatrix, causing white root rot of apple in Himachal Pradesh. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences, 8, 661–667.

Pasini, L., Prodorutti, D., Pastorelli, S., & Pertot, I. (2016). Genetic diversity and biocontrol of Rosellinia necatrix infecting apple in northern Italy. Plant Disease, 100, 444–452.

Peláez, F., González, V., Platas, G., Sánchez Ballesteros, J., & Rubio, V. (2008). Molecular phylogenetic studies within the Xylariaceae based on ribosomal DNA sequences. Fungal Diversity: an international journal of mycology, 31, 111–134.

Pérez-Jiménez, R. M. (2006). A review of the biology and pathogenicity of Rosellinia necatrix—The cause of white root rot disease of fruit trees and other plants. Journal of Phytopathology, 154, 257–266.

Pérez-Jiménez, R. M. (2008). Significant avocado diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes. European Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology, 2, 1–24.

Pliego, C., Kanematsu, K., Ruano-Rosa, D., De Vicente, A., López-Herrera, C., Cazorla, F. M., & Ramos, C. (2009). GFP sheds light on the infection process of avocado roots by Rosellinia necatrix. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 46, 137–145.

Pliego, C., López-Herrera, C., Ramos, C., & Cazorla, F. M. (2012). Develo** tools to unravel the biological secrets of Rosellinia necatrix, an emergent threat to woody crops. Molecular Plant Pathology, 13, 226–239.

Ruano-Rosa, D., Schena, L., Ippolito, A., & López-Herrera, C. J. (2007). Comparison of conventional and molecular methods for the detection of Rosellinia necatrix in avocado orchards in southern Spain. Plant Pathology, 56, 251–256.

Sánchez-Ballesteros, J., González, V., Salazar, O., Acero, J., Portal, M. A., Julián, M., Rubio, V., Bills, G. F., Polishook, J. D., & Platas, G. (2000). Phylogenetic study of Hypoxylon and related genera based on ribosomal ITS sequences. Mycologia, 92, 964–977.

Schena, L., & Ippolito, A. (2003). Rapid and sensitive detection of Rosellinia necatrix in roots and soils by real time scorpion PCR. Journal of Plant Pathology, 85, 15.

Schena, L., Li Destri Nicosia, M., Sanzani, S., Faedda, R., Ippolito, A., & Cacciola, S. (2013). Development of quantitative PCR detection methods for phytopathogenic fungi and oomycetes. Journal of Plant Pathology, 95, 7–24.

Schena, L., Nigro, F., & Ippolito, A. (2002). Identification and detection of Rosellinia necatrix by conventional and real-time scorpion-PCR. European Journal of Plant Pathology, 108, 355–366.

Schena, L., Nigro, F., & Ippolito, A. (2008). Integrated management of Rosellinia necatrix root rot on fruit tree crops. Integrated Management of Diseases Caused by Fungi, Phytoplasma and Bacteria. 137-158. Springer.

Shiragane, H., Usami, T., & Shishido, M. (2019). Weed roots facilitate the spread of Rosellinia necatrix, the causal agent of white root rot. Microbes and Environments, 34, 340–343.

Shishido, M., Kubota, I., & Nakamura, H. (2012). Development of real-time PCR assay using TaqMan probe for detection and quantification of Rosellinia necatrix in plant and soil. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 78, 115–120.

Smith, D. S., Maxwell, P. W., & De Boer, S. H. (2005). Comparison of several methods for the extraction of DNA from potatoes and potato-derived products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 53, 9848–9859.

Stadler, M., Kuhnert, E., Persoh, D., & Fournier, J. (2013). The Xylariaceae as model example for a unified nomenclature following the “one fungus-one name (1F1N) concept”. Mycology, 4, 5–21.

Sztejnberg, A., & Madar, Z. (1980). Host range of Dematophora necatrix, the cause of white root rot disease in fruit trees. Plant Disease, 64, 662–664.

Sztejnberg, A., Omary, N., & Pinkas, Y. (1983). Dematophora root-rot on avocado trees in Israel and development of a diagnostic method. Phytoparasitica, 11, 238–239.

Takemoto, S., Nakamura, H., Sasaki, A. & Shimane, T. (2009). Rosellinia compacta, a new species similar to the white root rot fungus Rosellinia necatrix. Mycologia, 101, 84–94.

Takemoto, S., Nakamura, H., Sasaki, A., & Shimane, T. (2012). Species-specific PCRs differentiate Rosellinia necatrix from R. compacta as the prevalent cause of white root rot in Japan. Journal of General Plant Pathology, 77, 107–111.

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A., & Kumar, S. (2013). MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30, 2725–2729.

ten Hoopen, G. M., & Krauss, U. (2006). Biology and control of Rosellinia bunodes, Rosellinia necatrix and Rosellinia pepo: A review. Crop Protection, 25, 89–107.

Tsao, P. H. (1970). Selective media for isolation of pathogenic fungi. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 8, 157–186.

Vaartaja, O. (1968). Pythium and Mortierella in soils of Ontario forest nurseries. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 14, 265–269.

van den Berg, N., Hartley, J., Engelbrecht, J., Mufamadi, Z., van Rooyen, Z., & Mavuso, Z. (2018). First report of white root rot caused by Rosellinia necatrix on Persea americana in South Africa. Plant Disease, 102, 1850.

Van der Merwe, J., & Matthee, F. (1974). Rosellinia-root rot of apple and pear trees in South Africa. Phytophylactica, 6, 119–120.

Vu, D., Groenewald, M., de Vries, M., Gehrmann, T., Stielow, B., Eberhardt, U., al-Hatmi, A., Groenewald, J. Z., Cardinali, G., Houbraken, J., Boekhout, T., Crous, P. W., Robert, V., & Verkley, G. J. M. (2019). Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Studies in Mycology, 92, 135–154.

White, T. J., Bruns, T., Lee, S., & Taylor, J. (1990). Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications, 18, 315–322.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Hans Merensky Foundation and the South African Avocado Growers’ Association for funding. We thank Prof. Carlos López-Herrera (Instituto de Agricultura Sostenible, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Spain), Dr. Stanley Freeman (Institute of Plant Protection, Agriculture Research Organization (ARO), Israel), Dr. Mery Dafny Yelin (MIGAL – Galilee Research Institute, Israel), and Louise Smit (ARC infruitec - Nietvoorbij, Stellenbosch, South Africa) for providing some of the R. necatrix isolates used in this study. We also thank Westfalia Fruit Estate and ZZ2 farms for supplying isolates and plant material.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Funding

Hans Merensky Foundation and the South African Avocado Growers’ Association.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Jesse Hartley and Dr. Juanita Engelbrecht. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Jesse Hartley and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Supplementary Information

Online Resource 1

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and actin gene sequences obtained from the Rosellinia isolates used in the study (PDF 105 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hartley, J., Engelbrecht, J. & van den Berg, N. Detection and prevalence of Rosellinia necatrix in South African avocado orchards. Eur J Plant Pathol 163, 961–978 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-022-02532-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10658-022-02532-8