Abstract

While previous research has extensively explored the correlation between pay gaps and firm innovation, the comprehensive investigation of various pay gaps within a unified framework remains an understudied domain. We advance the understanding of the intricate relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation by examining the tournament effect and social comparison effect. Through empirical analysis spanning the period from 2009 to 2019 of Chinese listed companies, our findings reveal a potential inverted U-shaped curve in the impact of all pay gaps on firm innovation. Specifically, the effects of internal pay gap and management pay gap exhibit the left half of an inverted U-shaped curve, while the external pay gap demonstrates a complete inverted U shape. Additionally, utilizing fsQCA, we unveil that small firms can stimulate innovation through management pay incentives, internal tournaments, or employee tournaments. Conversely, large firms can pursue diverse paths, including management equity incentives, strategic emphasis on low pay for firm growth, or a harmonious combination of management pay and equity incentives. The intricate interplay between pay gaps and firm innovation is contingent upon industry and firm characteristics. Consequently, our study underscores the importance of meticulously designing pay structures that align with strategic goals and unique attributes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, the relative income gap between different income groups in China has shown slight narrowing, while the absolute income gap continues to widen. The absolute per capita disposable income gap between the top 20% of the income group and the bottom 20% of the income group increased from 43,054 RMB in 2013 to 72,425 RMB in 2020 (Zhang and Li, 2021). In response to income inequality, the Chinese government has explicitly outlined its objective of achieving tangible progress in common prosperity by 2035.

With such a purpose, the Chinese government has made a series of efforts. From a regulatory perspective, the Chinese government has implemented “salary limit orders” multiple times for senior executives of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to alleviate the growing pay gaps within Chinese firms. In 2002, China began implementing an annual salary system for senior executives of SOEs, which stipulated that their annual salaries should not exceed 12 times the average employee wage. However, with the backdrop of rapid economic development and increased profits, this ratio has been surpassed. On September 16, 2009, the Chinese government set the upper limit for executive compensation in central SOEs at 20 times the average employee wage of the previous year. Starting on 1 January 2015, the Chinese government adjusted the upper limit of the pay gap for executives and employees in 72 state-owned enterprises 8-fold. In the past year, news related to “salary limit orders” in China has continued to emerge. In May 2022, the China Securities Association issued guidelines for securities companies to establish sound compensation systems and enhance the mechanism of compensation incentives and constraints. In August 2022, the Ministry of Finance introduced “salary limit orders” in the financial industry to control “gaps” in compensation, prioritize frontline employees, and establish a compensation recovery system.

Not only in China, but also globally, there has been a sustained concern and research focus on income inequality. In the context of the United States, numerous studies have sought to identify the causes and trends of changes in income inequality. Some research suggests that skill-biased technological changes and a sharp deceleration in the relative supply of college-educated labor in the 1980s have led to a significant increase in wage inequality in the United States since 1980 (Autor et al., 2008). Recent studies also emphasize the rising real wages of workers with graduate degrees, while the real wages of workers with lower levels of education have either declined or remained stagnant. The real income of men without a high school degree is now 15% lower than in 1980 (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2022). Furthermore, additional research, utilizing data from around the world, aims to pinpoint the sources of income inequality (Akerman et al., 2013; Mueller et al., 2017).

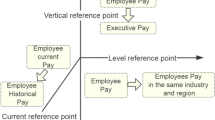

Recent research not only scrutinizes the sources of income inequality but also delves into its consequences (Buttrick and Oishi, 2017), notably its impact on firm innovation. Particularly, as income is considered one of the most potent investments for stimulating human capital and is intricately tied to technological innovation (Sheikh, 2012; Wang et al., 2020), studies suggest that the behavior of both managers and ordinary employees is influenced not solely by their absolute income but also by their relative income (Hu et al., 2023; Pan and Yi, 2023; Miao et al., 2020; Coles et al., 2018), as reflected in the pay gap. Studies have revealed that the pay gap between managers and CEOs (internal management pay gap), the pay gap between managers and employees (internal firm pay gap), and the pay gap between managers and peers within the same industry (external firm pay gap) all impact innovation within firms.

These studies are primarily based on two theories: tournament theory and social comparison theory. The tournament theory posits that an increase in pay gap will motivate employees to engage in innovative work. On the other hand, social comparison theory suggests that a wider pay gap may create a strong sense of unfairness among employees, hindering innovation within the organization. Based on the empirical findings that consistently support a positive correlation between pay gap and innovation, these studies endorse the consensus that tournament effects completely outweigh social comparison effects (e.g., Banker et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2022; Kong et al., 2017; Miao et al., 2020).

This raises two inquiries. Initially, under the assumption of a robust positive correlation between pay gaps and innovation, it posits that a firm striving for elevated innovation performance might necessitate the establishment of a substantial pay gap. Is the strategy of indiscriminately augmenting the pay gap effective and suitable for the majority of companies? Moreover, does such a pronounced pay gap not entail adverse consequences? Secondly, are the effects of diverse categories of pay gaps on firm innovation homogenized? If distinctions exist, where do these differences manifest?

The primary aim of this study is to answer these inquiries and make several contributions. Firstly, while we endorse both the tournament theory and the social comparison theory, we do not subscribe to the notion that the former entirely eclipses the latter. Both theories coexist, exhibiting varying degrees of influence under different magnitudes of pay gaps. Base on this, we identify and demonstrate that the relationship between pay gaps and innovation is not simply a “tournament effect” (solely increasing) but rather a nonlinear relationship influenced by multiple effects.

Secondly, our study goes beyond examining and comparing pay gaps among various entities in terms of their impact on innovation. We also differentiate innovation output quality through the number of citations for patents. Furthermore, we investigate the impact of certain firm-level factors on the aforementioned relationship. By varying and comparing the independent variables, dependent variables, and influencing conditions of the model, we reveal the sources and conditions of this nonlinear impact relationship between multiple pay gaps and firm innovation at a deeper level, which has been lacking in most of the previous research.

Thirdly, we uncover the impact of pay gaps on innovation and identify relevant firm characteristics. This approach enables us to provide practical managerial recommendations for specific firms to reconcile the contradiction between pay gaps and innovation. Overall, our research has a strong practical orientation.

Finally, for the first time, our study introduces the Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis(fsQCA) to research the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation. We utilize both internal and external factors as contextual variables within the framework of this relationship. Additionally, we simultaneously consider three types of pay gaps and management shareholdings as indicators of the pay system. By doing so, our research overcomes some limitations of previous studies and explores how firms of different sizes can leverage their internal and external factors to design pay structures that lead to high innovative performance. Thus, the findings of our research hold practical relevance and applicability.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: section “Literature review” provides a comprehensive review of the literature. Section “Theoretical analysis and hypotheses” presents the theoretical analysis and research hypotheses. Section “Method” describes the sources of the data and provides explanations for the variables used. Section “Empirical results and analysis” presents the empirical results and analysis, while Section “Exploration of heterogeneity” further discusses the heterogeneity observed. In section “The path to high innovation performance in firms”, we employ the fsQCA method to uncover pathways for achieving high innovation performance in both small and large sized firms. Finally, in section “Conclusion, discussion, and limitations”, we conclude the study by presenting key findings, discussing their implications and limitations, and providing an overview of future research directions.

Literature review

Review of research

Extensive research has investigated the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation, with a focus on single-type pay gaps. The reviewed studies fall into three main categories.

Firstly, research has explored the impact of pay gaps within top management on firm innovation. These studies examine the influence of pay gaps between managers and CEOs on innovation. Some findings suggest that pay gaps within management teams not only enhance the innovation motivation of highly paid managers but also encourage exploration among low-paid managers, resulting in a significant positive impact on innovation (Huang et al., 2022). Other studies indicate that pay gaps within top management teams can improve firm innovation efficiency (Hu et al., 2023), while some propose that such pay gaps may intensify the negative effect of CEO underpayment on innovation (Wang et al., 2020).

Secondly, research has investigated the impact of internal pay gaps within firms on innovation. The majority of studies in this area focus on internal pay gaps, specifically the gaps between managers and employees. These findings largely support tournament theory, suggesting a positive relationship between internal pay gaps and innovation output (Kong et al., 2017; Fu and Yao, 2019; Pan and Yi, 2023; Miao et al., 2020). Research examining inventor innovation efficiency and willingness to participate also indicates that widening internal pay gaps have a positive effect on firm technological innovation (Zhao and Wang, 2019). Similar findings have been observed in foreign research, emphasizing the importance of management pay premiums for firm performance, even when tested with samples of U.S. companies with smaller pay gaps (Banker et al., 2016).

Thirdly, research has explored the impact of external pay gaps among industry peers (industry tournament) on firm innovation. Some studies examine the difference between average management pay in a firm and the average management pay of the highest-paying firm in the same industry (external pay gap). Research has identified a positive correlation between firm performance, risk, and innovation with external industry pay gaps. The strength of the industry tournament effect increases when industry, firm, and management characteristics indicate a greater likelihood of CEO mobility and ambitious managers (Coles et al., 2018). Domestic research in China has also confirmed this point, finding a positive relationship between industry tournament incentives and firm innovation output, indicating that such incentives enhance innovation (Mei et al., 2019). However, certain studies have partially challenged this view, suggesting that industry tournament incentives promote incremental innovation but inhibit radical innovation. The research highlights the presence of strategic innovation behaviors within firms that cannot be solely attributed to industry tournament incentives (Sun et al., 2023).

Some studies present conflicting perspectives, proposing that the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation and performance is nonlinear. Research suggests that in situations with low pay inequality between managers and employees, exacerbating inequality harms firm productivity. Conversely, in situations with high pay inequality, it promotes productivity (Luo et al., 2019). Additionally, comparing state-owned and nonstate-owned firms in the Chinese context may contribute to understanding the aforementioned heterogeneity. Nonstate-owned firms primarily focus on maximizing economic interests, while state-owned firms have multiple objectives, including economic goals as well as social goals such as job creation, social stability maintenance, and the execution of industrial policies. This inconsistency in objectives places nonstate-owned enterprise employees in a more competitive environment than their state-owned counterparts, potentially amplifying the motivational effects of pay gaps for the former (Li et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2023). The hypothesis is as follows:

H2b: Compared to that of the non-innovation-oriented firm group, the impact of the three pay gaps is more significant in the innovation-oriented firm group.

H2c: The effects of both internal and external pay gaps on employee motivation are more prominent in nonstate-owned firms, favoring firm innovation.

H2d: Compared to those of nonstate-owned firms, the negative effects of increased external pay gaps on firm innovation outputs are less significant for state-owned firms, resulting in an overall weaker impact.

The moderating role of firm competitive position

Generally, firms in highly competitive positions exhibit distinct advantages in terms of funding, technology, profit margins, and employee pay compared to firms in less competitive positions. The internal organizational structures of these organizations are also complex, with intensified internal competition. From the perspectives of employees and managers, the current level of pay is already substantial, and the unpredictability of higher position transitions increases the difficulty of winning internal tournaments. In contrast, firms in less competitive positions face relatively challenging tasks in maintaining their survival and long-term development. Intense competition prompts these firms to allocate more resources to innovation activities (**a and **ao, 2023; de et al., 2022) and establish better pay systems to incentivize innovation. These firms are willing to allocate a larger proportion of their profits to incentivize more employees to overcome the disadvantages of a lower competitive position (Jia and Wei, 2019). For employees within firms in low competitive positions, they have more opportunities to showcase their talents, face fewer hurdles in internal promotions, and experience more pronounced motivational effects from pay gaps. The hypotheses are as follows:

H3a: An increase in a firm’s competitive position inhibits the motivating effect of the pay gap among top management on firm innovation.

H3b: An increase in a firm’s competitive position inhibits the motivating effect of the internal pay gap on firm innovation.

H3c: An increase in a firm’s competitive position suppresses the motivating effect of the external pay gap on firm innovation, and after reaching a turning point, it strengthens the inhibitory effect.

The complete research model is depicted in Fig. 2.

Method

Data and sample

The sample used in this study consists of all listed companies on the China A-share market from 2009 to 2019, spanning various industries except for the financial industry. The period starting in 2009 was chosen to account for the impact of the financial crisis and the implementation of the “pay cap” policy for the management of state-owned firms. As the data includes patent quality, which takes time to be recognized by the market and determine citation counts, the data cutoff is set at 2019 (with the citation count statistics extending to 2022). The patent data for the sample firms are obtained from the Chinese National Intellectual Property Patent Database, which provides comprehensive annual patent application numbers and citation counts, allowing for the measurement of patent quality. Other data sources include the CSMAR database and the WIND database, which compile a range of observed variables through the organization of company annual reports. The data were subjected to the following steps: excluding the financial industry due to its unique accounting characteristics; winsorizing all continuous variables at the 1st and 99th percentiles to mitigate the influence of extreme values; removing samples with abnormal trading statuses such as special treatment (ST) and protection (PT); and eliminating listed companies with missing key data. The final sample consists of 18,670 observations. In similar published studies, to our knowledge, our sample size is the largest.

We processed all the data and validated all hypotheses using Stata 17 software.

Variable definitions

Dependent variables

Based on the previous literature, this study primarily focuses on three categories of dependent variables. (Unlike in the United States, equity-based pay is relatively limited in coverage and proportion in Chinese firms. Therefore, equity-based pay is not included in the study’s definition of pay. However, the study controls for managerial shareholding in the regression analysis.)

-

(1)

Internal Pay Gap among Top Management (FMPG): To address potential issues of extreme values or transient situations where the highest-paid management’s pay may not be sustainable or achievable by other management after winning a tournament, this study measures FMPG by taking the average pay of the top three management practices and subtracting the average pay of the remaining management practices. The formula is as follows:

FMPG = ln [(Total pay of top three managements/3) - (Total pay of management personnel - Total pay of top three managements)/(Number of directors + Number of managements + Number of supervisors - Number of independent directors - Number of directors, supervisors, or managements not receiving pay - 3)]/10.

-

(2)

Internal Pay Gap (FIPG): Following previous studies and for the sake of comparability, this study defines FIPG as one-tenth of the logarithmic difference between average managerial pay (AMP) and average employee pay (AEP).

AMP = Total annual pay of directors, supervisors, and managements/ (Number of directors + Number of managements + Number of supervisors - Number of independent directors - Number of directors, supervisors, or managements not receiving pay).

AEP = (Total employee pay + Cash payments to and on behalf of employees - Total annual pay of directors, supervisors, and management)/Number of employees.

FIPG = [ln(AMP - AEP)]/10.

-

(3)

External Pay Gap (FOPG): To facilitate comparison with FMPG and FIPG, this study measures the external pay gap by taking one-tenth of the logarithmic difference between the maximum average managerial pay (AMP_max) in the industry and the firm’s average managerial pay (AMP).

FOPG = [ln(1 + AMP_max - AMP)]/10.

Additionally, this study employs the ratios of the abovementioned variables for robustness checks. For example, FOPG_robust = AMP_max/AMP. These ratio-based measures are consistent with previous research.

Independent variables

The independent variables capture measures of innovation, which are commonly assessed from the perspectives of innovation inputs and outputs. Considering the focus on firm innovation outputs in most studies, we employ the natural logarithm of the number of patent applications as a measure of firm innovation output (Patent). However, using the number of patent applications alone as a measure of innovation has limitations because it overlooks the quality of patents. Relying solely on the number of patent applications underestimates the innovation output of firms that apply for high-quality patents.

To address this limitation, we introduce the citation count as a criterion for classifying patents. The number of citations received by a patent is strongly correlated with its importance in the respective technological field and serves as a critical measure of patent quality. Specifically, based on the citation count, we construct a kernel density plot of patent citations (Fig. 3) and perform a statistical analysis to identify significant declines at various percentile cut-offs within the 1,334,075-patient sample. The observations are as follows: the top 1% corresponds to more than 14 citations, the top 3% corresponds to more than 8 citations, the top 5% corresponds to more than 6 citations, and the top 10% corresponds to more than 4 citations.

However, the original citation count of patents still has two significant limitations: industry technological differences and time section differences. To address these limitations, following the approach of Sun et al. (2023), this study classified patents within the same industry and time period. Within each category, the number of patents in the top 5% of citation counts was calculated and matched with the sample of listed companies. The natural logarithm of these patent counts plus one was used to measure the high-quality innovation output of listed companies (Patent_high). Simultaneously, the difference between the total number of patents applied for by listed companies in a given year and the number of high-quality innovations was defined as the low-quality patents, and the natural logarithm of these low-quality patents plus one was defined as the low-quality innovation output of listed companies (Patent_low). Furthermore, a binary variable (Bs) was used to identify whether a firm had high-quality innovation output. If a firm had high-quality innovation output, Bs was assigned a value of 1; otherwise, Bs was assigned a value of 0.

Controlled variables

Building upon the previous literature on firm innovation, this study controlled for a range of firm and industry characteristics that may affect innovation. These variables include firm size, the leverage ratio, profitability, the share of fixed assets, firm age, the sales growth rate, state ownership, CEO-chair duality, the proportion of independent directors, managerial shareholding, Tobin’s Q, and the Herfindahl index. Considering the potential nonlinear relationship between industry concentration and firm innovation, the square term of the Herfindahl index was included. Additionally, based on the research hypotheses, the study selected the Lerner index as a moderating variable. The detailed definitions of each controlled variable are provided in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis of the variables

Table 2A below presents the descriptive statistics of each variable. Out of the 18,670 listed companies in the sample, the average number of patents applied for per year is 44.10, with an average of 3.060 high-quality patents and 40.97 low-quality patents. The average values of FMPG, FIPG, and FOPG are similar, indicating that the three dimensions of the income gap are comparable and justifying their inclusion in the same research framework for cross-sectional comparison. Additionally, among these listed companies, 33.7% are state-owned firms, 28.9% have CEO-chairperson duality, and the average proportion of independent directors is 37.4%. Finally, based on the criterion of having high-quality innovation patents, 51.4% of the companies follow an innovation-oriented strategy. And the correlation matrix of the variables is provided in Table 2B.

Empirical results and analysis

Results of testing H1a, H1b, and H1c

To examine the impact of the pay gap on innovation output, this study conducted regression analysis using patents as the dependent variable and pay gaps (FMPG, FIPG, and FOPG) as the independent variable, as shown in Model (1).

In Model (1), the dependent variable Patenti,t represents the total number of patents applied for by firm i in year t. The independent variables that measure pay gaps are FMPG, FIPG, and FOPG. The regression analysis includes a set of control variables, as mentioned in Table 1, including Controls (referring to the various control variables described in the descriptive statistics). Additionally, the regression model incorporates industry and year-fixed effects. The results of the regression analysis are presented below:

The findings suggest that preliminary support is found for H1a and H1b. Table 3 reports the regression results for Model 1 in columns (1), (2), and (3). The coefficients of FMPG and FIPG are positive and significant at the 1% level, indicating that increasing the pay gap within the management team and between the management team and employees as a whole enhances firms’ patent output. Conversely, the coefficient of the external pay gap (FOPG) is negative, indicating that increasing the external pay gap reduces firms’ innovation output.

These findings suggest that expanding the pay gap among management teams and within organizations enhances firms’ innovation output, supporting tournament theory. On the other hand, the effect of the external pay gap is opposite, as increasing the external pay gap leads to a decrease in firms’ innovation output.

The coefficients of the control variables indicate that larger firm size, higher leverage ratio, higher asset return rate, lower proportion of fixed assets, younger firm age, and higher Tobin’s Q are associated with greater innovation output measured by patent applications. Additionally, a higher percentage of management ownership is positively correlated with firms’ innovation output, further demonstrating the importance of optimal contracts. The age of the CEO inhibits innovation, while the tenure of the CEO promotes firm innovation. The influence of the proportion of independent directors, growth, and the combination of chairperson and CEO roles is not significant.

Finally, we find that in China, state-owned listed companies have greater innovation output than nonstate-owned listed companies do, and the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) exhibits a significant inverted U-shaped relationship with firms’ innovation output. Completely monopolistic and intensely competitive industry environments are unfavorable for firm innovation. In the former environment, firms may be inclined to maintain the status quo, while in the latter environment, firms may adopt low-risk strategies to survive intense competition rather than engaging in innovative activities. In other words, as industry competition decreases, firms’ innovation output initially increases and then decreases. Taking the results in column (1) as an example, when HHI = 0.395, the positive impact of HHI on firms’ innovation output reaches its peak. Considering that the majority of the sample HHI values are less than 0.388 (with the 70th percentile at only 0.15), a decrease in industry competition overall promotes an increase in firms’ innovation output.

To further examine the nonlinear relationships between pay gaps and firm innovation, quadratic terms for FMPG, FIPG, and FOPG are included in the regression analysis. The coefficients of FMPG, FIPG, and their quadratic terms are all significant at the 5% level, confirming the nonlinear relationships. However, the turning points for the FMPG and FIPG exceed the range of the data, leading to the rejection of a complete inverted U-shaped relationship. On the other hand, the coefficient of FOPG2 (quadratic term of FOPG) was significant at the 1% level, and the turning point of FOPG fell within the range of the data. This finding indicates that as the external pay gap increases, firms’ innovation output follows an inverted U-shaped pattern, providing support for H1c.

These nonlinear relationships further highlight the complex interplay between pay gaps and firm innovation. The strength and significance of various factors influencing innovation output vary with changes in different pay gaps, reflecting the effects of tournament theory and social comparison theory. The findings suggest that while increasing internal pay gaps within the management team and between the management team and employees can enhance innovation output, increasing external pay gaps has a negative impact on innovation. These results emphasize the importance of carefully managing pay gaps within organizations to effectively motivate employees and drive innovation.

Results of testing H1d

In comparison to the regression relationship between individual pay gaps and firm innovation, this study is more interested in comparing the relative importance of multiple pay gaps on firm innovation output. Due to differences in the scales of the variables, it is not appropriate to directly compare the regression coefficients of the three pay gaps in the regression model for firm innovation output. Therefore, following the approach of Flannery and Rangan (2006), this study standardizes each variable to compare the relative importance of the three pay gaps in explaining firm innovation output. Before standardizing the variables, this study conducted tests for multicollinearity and correlation among all variables, and all variables met the criteria for multicollinearity and correlation (all VIF values were <10, with an average VIF value of 2.28, and correlations were all <0.65).

In Table 4A, different combinations of pay gaps are included in the regression models for firm innovation output. In column (1), which includes FMPG and FIPG, it is observed that the coefficient of FMPG becomes negative when controlling for FIPG, indicating a negative correlation between FMPG and firm innovation. This finding suggests that a larger pay gap between CEOs and the management team may lead to frustration among managers, considering the pressure from the convergence of ordinary employee salaries. Column (2) includes FMPG, FOPG, and the quadratic term FOPG. The coefficients of both FMPG and FOPG are not significant, indicating that when comparing with external industry peers, managers become less sensitive to both vertical and horizontal pay gaps within the organization. This can be explained by the desire for promotion being suppressed by the attractiveness of job hop**. In column (3), FIPG, FOPG, and the quadratic term FOPG are included. The coefficients of both FOPG and its quadratic term significantly decrease, suggesting that the pay gap between managers and employees provides managers with a sense of accomplishment and respect, reducing their inclination to switch jobs. Finally, in column (4), all pay gaps are simultaneously included in the regression model.

Table 4B evaluates the economic significance of the three pay gaps by comparing their ability to explain the variations in FMPG, FIPG, and FOPG. In column (1), the coefficients from column (1) of Table 4A (after standardization) are applied. It is calculated that a one-standard-deviation increase in FMPG leads to a decrease of approximately 0.044 in fitted firm innovation output (Patent), which represents a 3.03% decrease relative to its standard deviation (1.454). In contrast, a one-standard-deviation increase in FIPG results in an increase of 0.054 in the fitted firm innovation output, which represents a 3.71% increase relative to its standard deviation. In columns (2) and (3) of Table 4B, the coefficients (after standardization) are applied from columns (2) and (3) of Table 4A, respectively. When FOPG is relatively low, especially below the 25th percentile, FOPG has greater relative importance in influencing firm innovation output. However, the significance of some variables in these two columns is not high. In column (4), all three pay gaps are simultaneously included. Consequently, the fitted firm innovation output decreases by 0.045 when FMPG changes by one standard deviation, increases by 0.053 when FIPG changes by one standard deviation, and varies between a 4.81% increase and a 1.65% decrease in firm innovation output when FOPG changes by one standard deviation within the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Overall, the impact of FIPG on firm innovation output is the most significant, followed by FMPG, which exhibits an inhibitory effect when considering other pay gaps. The importance of FOPG for firm innovation output fluctuates with the value of FOPG, but it is generally not as significant. When removing firm fixed effects, the importance of FMPG in influencing firm innovation output decreases significantly, while the importance of FIPG remains the most crucial.

The comparative results confirm H1d. Among the three pay gaps, FIPG is the most important variable for incentivizing firms to increase their innovation output. When controlling for other pay gaps, the impact of FMPG on firm innovation becomes negative, and its relative importance remains significant. The impact of FOPG on firm innovation becomes less significant due to the interference of the first two pay gaps.

These research findings have practical implications. The motivational impact of external tournaments on managers may be offset by the incentives of various internal pay tournaments within the firm. This reflects that well-designed internal pay tournaments may retain talented managers. Additionally, establishing appropriate internal pay gaps and managerial pay gaps is crucial. The former can motivate employees and enhance managerial identification, thereby promoting firm innovation. However, an excessively large managerial pay gap may lead to managerial dissatisfaction, negatively impacting firm innovation and potentially offsetting the motivational effects of the former. Therefore, innovative-focused firms need to establish a balanced compensation system, taking into account the industry’s highest average salaries, to address both types of pay gaps and maximize the value of human capital, especially managerial human capital.

Robustness checks

To ensure the reliability of the research conclusions, we conducted robustness tests as follows:

First, considering that the innovation process of firms takes time, we included lagged values of all independent and control variables in the regression analysis. The results show that the signs and significance of the regression coefficients for all pay gaps remained unchanged, and the magnitude of the coefficients did not vary significantly. This finding indicates that the results of this study are robust and that the conclusions are further strengthened when considering the long-term nature of innovation activities.

Second, to further mitigate the impact of outliers on the research conclusions, we winsorized all variables at the 2% and 0.5% levels in a two-tailed manner. The conclusions of this study have remained unchanged.

Third, considering the lagged effect of the pay cap policy implemented in 2009, we limited the sample to the period of 2012–2019. Additionally, some individuals with missing control variables were excluded, resulting in an expanded sample size of 18,670 for the regression analysis. The results of this study remained unchanged.

Finally, we conducted sensitivity tests by referring to similar research studies. Changes were made to the control variables and alternative measurements of the explanatory variables (such as measuring pay gaps as ratios). The main conclusions of this study remained unchanged.

Endogeneity

This study has several specific endogeneity issues. Firstly, pay gaps may be influenced by firm performance and business risk. Innovation, as a high-risk activity, is closely related to firm performance, especially long-term performance. For example, innovative companies often have greater efficiency, and their pay structures may differ significantly from those of low-efficiency companies. A reverse causal relationship may exist between innovation and pay gaps. In other words, a firm’s innovation activities may, in turn, affect the pay gaps within the firm, within the management team, and ultimately the external pay gap. High levels of innovation output imply high employee performance, leading to increased pay for these employees and a reduction in pay gaps. This could potentially undermine the incentive effect of reducing pay gaps.

Secondly, hidden payments such as bonuses, equity dividends, allowances, and benefits may mitigate the adverse effects of pay gaps on employees. The perceived unfairness of a high pay gap can be offset by these hidden payments, which are also related to firm performance and innovation outcomes. However, it is challenging for this study to control for these hidden payments. Therefore, in firms with high levels of innovation, the adverse effects of large pay gaps on innovation may be overestimated in this study (due to the lack of measurement for high benefits), resulting in an underestimation of the motivational effect of pay gaps on firm innovation.

Lastly, regarding omitted variables, the maturity of the industry, firm growth opportunities, and the level of government policy support are difficult to measure using existing specific indicators. However, these factors can simultaneously influence the pay gap and innovation within firms. For example, a firm in an emerging industry with good growth prospects and strong government support may have greater demand for talented managers and be willing to offer higher pay. These companies are more likely to create or be required to generate higher innovation output. This study captures these influences by including firm-level and industry-level fixed effects and control variables that reflect firm growth prospects, such as the sales growth rate and Tobin’s Q. To address the issue of reverse causality, this study further employs IVR methods.

When using instrumental variables, it is crucial to identify suitable instruments that are highly correlated with the explanatory variables but independent of the error term. In other words, the instrumental variables should influence only the explained variable through the explanatory variables. For the internal pay gaps (FMPG and FIPG), we refer to the methods used in Dhaliwal et al. (2014) and Krolikowski, Yuan (2017) and utilize the differences between the lagged two-year and three-year average management pay gaps of peer firms and the corresponding pay gaps within the focal firm (L2.ΔFMPG, L3.ΔFMPG and L2.ΔFIPG, L3.ΔFIPG) as instrumental variables. On the one hand, when formulating pay policies, firms often refer to the existing pay structures of peer firms, especially when adjusting pay structures to motivate employees during periods of poor firm performance. This reference to the pay structures of high-performing peer firms becomes more apparent. Firms adjust their own pay structures based on the differences between their pay structures and those of peer firms. On the other hand, it is highly unlikely that the average pay gap between peer firms influences the focal firm’s innovation output. This lack of correlation is further strengthened by the one-year and two-year lags.

For the external pay gap (FOPG), the method of using average pay gaps in the industry is not applicable. This study refers to the method used by Coles et al. (2018) and employs the total pay of the management team in the industry and its lagged one-year term (ln(AMP_total) and L.ln(AMP_total)) as instrumental variables for FOPG. These instrumental variables reflect the total payment capacity of the industry, which becomes a reference for the management team when evaluating their own pay gaps compared to other management teams within the industry. High-level managers in industries with substantial pay capacity will demand higher pay, resulting in larger external pay gaps. These instrumental variables are also unlikely to influence the innovation output of individual firms. Table 5 presents the 2SLS results using instrumental variables.

In the first stage of the 2SLS model, we find a convergence trend between the firm’s internal pay gap and the management team’s internal pay gap and between the firm and the corresponding average pay gap within the industry. In other words, the greater the difference between the firm’s pay gap and the industry average pay gap is, the more likely the firm’s pay gap will continue to expand. This indicates a strong correlation between the instrumental variables and the explanatory variables, consistent with the expected results. Similarly, for the external pay gap, the stronger the industry’s payment capacity for managers is, the more likely the overall external pay gap will widen, aligning with the expectation for instrumental variable selection.

In the second stage of the 2SLS regression, we find that after using instrumental variables, the regression coefficients of the explanatory variables remain significant (the coefficients of FMPG and FIPG are significant at the 1% level, and the coefficient of the quadratic term of FOPG is significant at the 5% level); additionally, the direction of the coefficients remains unchanged, consistent with the baseline regression results (larger coefficients, consistent with the addressed endogeneity issues). This indicates a positive causal effect of the three types of pay gaps on firm innovation output.

Regarding the validation of the instrumental variables, we confirm the correlation between the instrumental variables and the explanatory variables, and the results of the overidentification test indicate that the selected instrumental variables are exogenous.

Furthermore, after further controlling for firm-level fixed effects, we find that the correlation between the instrumental variables and the explanatory variables becomes less significant for the lagged two-year instrumental variables. However, the lagged one-year instrumental variables still confirm the aforementioned conclusions.

Exploration of heterogeneity

Results of testing H2a

Based on the classification of innovation output mentioned earlier, this study conducted regressions using the natural logarithm of high-quality patents (those ranked in the top 5% of citations within the year and industry) and low-quality patents (remaining patents) against the three types of pay gaps, as shown in Table 6.

The regression results confirm the validity of H2a. As shown in Table 6, an increase in FMPG has a stronger positive effect on high-quality innovation output than on low-quality innovation output. This could be attributed to the fact that when managers are promoted to the CEO position, they place greater importance on breakthrough innovations and high-quality patents than on a large quantity of low-quality patents. The former may have a much greater impact on managers’ performance rewards. On the other hand, FIPG has the opposite effect, with a stronger positive impact on low-quality innovation output. This is because achieving a higher output level, particularly in terms of quality, requires greater investment, more time, and greater risk. To win the promotion race, nonmanagerial employees are more inclined to attain faster innovation results, even if their quality is lower. The gap between these two findings may be due to the greater difficulty that ordinary employees face in develo** genuinely high-quality innovation outputs, while managers with more resources and the ability to organize teams are more likely to do so. For the external pay gap (FOPG), the inflection point for the high-quality innovation group (column (5)) is delayed, indicating that the FOPG has a relatively larger incentive effect on high-quality innovation. And the negative effects of increasing FOPG on high-quality innovation output are also delayed. This delay may be due to managers’ consideration of high-quality innovation output as more crucial when considering industry job mobility. The results in the table demonstrate that managers are more sensitive to high-quality innovation output in response to pay gaps, while employees are more sensitive to low-quality innovation output. Thus, H2a is supported.

The establishment of H2a signifies that firm managers play a crucial role in driving innovation activities, particularly in the realm of high-quality innovation. This finding aligns with existing research conclusions on executive behavior and underscores the significance of optimizing incentive mechanisms for company managers (Acemoglu et al., 2022). Our preliminary findings offer insights into corporate governance, suggesting that widening the pay gaps within executive teams can effectively promote innovative behavior within the organization. Furthermore, it suggests that the expectations of company owners from executives likely manifest in the realm of valuable high-quality innovation.

In a subsequent industry-specific examination, we observed that the impact of the three types of pay gaps on high-quality innovation is more pronounced in the manufacturing sector compared to the service industry (due to space constraints, the details are not presented in the charts). This observation suggests that management teams in the service industry may have more performance options beyond innovation, whereas executives in the manufacturing sector may exhibit a greater focus on innovation activities, particularly those related to high-quality innovation.

Results of testing H2b

According to the criterion of whether a firm applies for high-quality patents in a given year, this study divided companies into an innovation-oriented group (51.9% of companies with high-quality patents) and a non-innovation-oriented group (48.1% of companies without high-quality patents). Regression analyses were then conducted separately for each group using the three types of pay gaps.

The results of the empirical study support H2b. In Table 7, the effects and significance of the three pay gaps are significantly greater in the innovation-oriented group than in the non-innovation-oriented group. This is likely because innovation-oriented companies have a more conducive team atmosphere, pay and reward mechanisms, and promotion systems that are more aggressive. Both the management and employees of these companies perceive greater opportunities than do non-innovation-oriented companies, which further motivates them to showcase their talents and work harder, resulting in a more pronounced impact on innovation within the firm. For the external pay gap, employees and management in the low innovation-oriented group may be more content with the status quo, leading to a lack of sensitivity to changes in the external pay gap.

Results of testing H2c and H2d

Considering the presence of numerous state-owned firms in China, these entities exhibit interesting characteristics in the unique political environment of China. This study argues that the heterogeneity between state-owned and nonstate-owned firms in the Chinese context is worth investigating. The regression results are presented in Table 8.

Comparing columns (1) and (4) with columns (2) and (5) of Table 8, it is evident that the significance and regression coefficients of FMPG and FIPG are significantly greater for nonstate-owned firms than for state-owned firms. For the variable FOPG, overall, its impact on innovation is more significant for nonstate-owned firms. Additionally, the inflection point of FOPG occurs earlier in nonstate-owned firms than in state-owned firms, indicating that employees and management in nonstate-owned firms are more prone to frustration due to large external pay gaps. This could be attributed to the fact that employees and managers in nonstate-owned firms are more likely to compare their pay horizontally and perceive it as unfair than to the greater benefits and social status associated with state-owned firms. When FOPG increases (indicating lower average firm-level pay), the theories of fairness and relative deprivation become more pronounced, leading to a quicker manifestation of the negative impact of pay gaps on innovation.

The empirical findings support H2c and H2d. The incentivizing effect of pay gaps is stronger for nonstate-owned firms, while the negative impact of external pay gaps is less pronounced for state-owned firms.

The conclusion above reinforces the causal mechanism of this study, indicating that pay gap influences firm innovation through its impact on employee behavior. We believe that in more stable state-owned firms where promotion opportunities are more challenging, employees are less motivated by pay gaps, and their tolerance for excessive pay gaps is higher. This results in the weakening of the impact of the three types of pay gaps on innovation in state-owned enterprises, regardless of whether it is an incentive or inhibitory effect.

Results of testing H3

Based on the hypothesis, this study incorporates moderating variables (FLerner) and interaction terms between the moderating variables and the three types of pay gaps in the regression. The results are presented in the following table (Table 9). Table 9 shows that all interaction terms between the moderating variables and the explanatory variables are significant at the 5% level, indicating that firm competitiveness has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation. In columns (1) and (2), the regression coefficients of the explanatory variables and the moderating variables are positive, while the regression coefficients of the interaction terms are negative. This finding suggests that an increase in firm competitiveness inhibits the motivating effect of pay gaps on firm innovation.

By interpreting the regression coefficients of the variables, it is found that when FLerner is low, an increase in FMPG and FIPG stimulates firm innovation. However, as FLerner increases, this motivating effect is suppressed to the extent that when FLerner is high, an increase in FMPG and FIPG becomes detrimental to firm innovation. H3a and H3b are confirmed, indicating a strong negative moderating effect of firm competitiveness on the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation.

The previous analysis confirmed the inverted U-shaped relationship between FOPG and firm innovation. After introducing the moderating variables, the inverted U-shaped curve shifts to the lower right as FLerner increases. In other words, in high-competitive firms, the inhibiting effect of FOPG on firm innovation is more pronounced than that in low-competitive firms. In other words, an increase in firm competitiveness weakens the motivating effect of FOPG on firm innovation and strengthens its detrimental effect after a later inflection point. H3c is supported.

In summary, the moderating effect of firm competitiveness on pay gaps has been confirmed. Overall, an increase in firm competitiveness weakens the motivating effect of pay gaps on firm innovation and amplifies the potential negative effects.

The confirmation of H3 similarly strengthens the proposed mechanism of how pay gaps influences firm innovation in this paper. We argue that with an increase in firm competitiveness, employees’ compensation tends to rise, and the competition for promotions becomes more intense. Consequently, this evaluation of current satisfaction with compensation and the perceived challenges in career advancement diminishes the motivational impact of higher-level pay incentives.

The path to high innovation performance in firms

Method, data, and samples

In addition to studying the impact of various pay gaps on firm innovation, we also focus on the question of how firms aspiring to achieve high innovation performance should set these pay gaps. Previous research has shown that the relationship between pay gaps and firm innovation is not static but rather changes with various internal and external factors, posing a challenge for managers and owners in setting these gaps.

In this section, we employ fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to explore the interaction between various pay gaps and the internal and external factors of companies and how they ultimately affect firm innovation performance. We selected three types of pay gaps—firm age, firm growth, organizational complexity (board), industry concentration (HHI), and managerial shareholding (Mshare) as the variables.

The rationale for selecting these variables is grounded in several key considerations. Firstly, considering the potential issue of observed data being less than the number of possible configurations, it is advisable to avoid an excessive number of variables in the fsQCA analysis. The chosen variables align with prior research, considering them as crucial factors influencing firm innovation. More importantly, based on the research conclusions presented earlier, pay gaps impact firm innovation through their influence on employee perceptions and behaviors. The selected variables are those referenced by employees when making judgments on pay fairness and incentives. Additionally, we require these variables to be easily observable and perceptible, such as company age, organizational complexity, and expected growth.

Furthermore, this selection provides relatively operational criteria for those designing firm salary systems. If the introduced variables are overly complex, the practical significance of the research findings becomes comparatively limited. Lastly, the purpose of selecting these variables is to serve as a contrast to the regression results discussed earlier. The preceding discussion confirms that the impact of pay gaps on firm innovation is influenced by factors such as business strategy, property rights, and competitive position. More intuitive factors are chosen as control variables, as their impact on the mentioned relationships is likely not a simple linear net effect but a more complex configuration. In other words, employees’ perceptions of pay fairness and motivation depend on their comprehensive impression of the company, shaped by their perceptions of factors such as company age, organizational complexity, and industry competitiveness.

Case selection: QCA, as a method initially applied in the field of sociology, emphasizes case orientation (Greckhamer et al., 2013). Therefore, the selection of cases is crucial. All the samples were selected and matched based on the following criteria.

Firstly, the criterion we adopted is the selection of firm samples where the pay gap significantly influences innovation. According to conclusions drawn from previous literature (e.g., Sun et al., 2023) and the preceding sections, the impact of pay gap on innovation is more pronounced in non-state-owned firms and manufacturing firms. Therefore, samples were drawn from the manufacturing sector and non-state-owned firms. Secondly, concerning the time point for sample selection, to mitigate the potential impact of the COVID-19, we set the chosen time frame before 2019. Furthermore, considering the continuity of sample data, we opted for the year 2017 as the primary sample year, conducting robustness tests using data from the same enterprises in 2016 and 2018. Simultaneously, to enhance the practical significance of the results, and given that firm size is a crucial variable influencing innovation and is challenging to change in the short term, this study divided the samples into two groups based on the size of the firms. Each group included positive cases with high innovation performance and negative cases with low innovation performance. Ultimately, in each group, we selected 70 listed companies as research samples.

Variable calibration: Considering that all the variables are continuous variables and based on the distribution of the data and previous fsQCA studies on firm innovation (Fiss, 2011; Li et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2022), direct calibration was applied to all the variables in this study. Except for Board and Mshare, all the variables were calibrated using the 95th percentile as the threshold for full membership, the 5th percentile as the threshold for no membership, and the 50th percentile as the crossover point. For the Board and Mshare variables, as the first decile is close (many firms have a low proportion of shares held by top management), the 95th percentile was used as the threshold for full membership, the 15th percentile was used as the threshold for no membership, and the 50th percentile was used as the crossover point.

Sufficiency analyses

Similar to the other QCA method, we first conducted a necessity analysis on the causal variables to determine whether the set of high innovation outcomes for large- and small-scale firms is a subset of any single causal variable. Using the fsQCA 3.0 software, we found that the consistency level between most causal variables and their negations was <0.9, indicating that effective innovation activities in firms require more than just a single factor. Instead, organic integration of various elements is necessary. A simple tournament-based pay system may not be suitable for all firms, and firms need to design appropriate pay systems based on their own characteristics. However, there were exceptions for a certain variable. For small-scale firms, the “Board” variable has a consistency level of 1 with its negation, indicating that a simple organizational structure is a necessary condition for innovation activities in small firms. An overly complex organizational structure poses significant obstacles to innovation in small firms. However, this condition clearly does not apply to large-scale firms.

Contingency analyses

The key objective of using fsQCA is to identify the configuration of causal variables that lead to high innovation performance in firms. In other words, this study aims to determine which combinations of the three tournament-based pay variables, along with specific firm characteristics and external factors, serve as necessary conditions for achieving high innovation performance. The configuration analysis is based on the construction of a truth table and the setting of thresholds. In this study, both the large and small-scale firm groups consisted of 70 patients, which is considered a small sample size. In accordance with similar studies, a frequency threshold of 1 and an initial consistency threshold of 0.8 were used. The truth table was further refined based on the criterion that PRI consistency should be equal to or greater than 0.70 to reduce the possibility of simultaneous subset relationships between high and non-high innovation performance cases.

Considering that innovation in firms is a complex, long-term, and challenging activity that cannot be solely determined by a single causal variable, the results of the necessity analysis for individual conditions indicate that, except for the “existence” of the Board variable in small-scale firms, all other conditions were selected as “existence or absence” when faced with the question of “which states of the eight conditions would lead to high innovation performance in firms.” This was done to minimize artificial counterfactual analysis. Table 10 reports the configurations of conditions for high innovation performance in both large- and small-scale firms. The consistency level indicates the extent to which the configuration serves as a necessary condition for high innovation performance, while the raw coverage indicates the proportion of cases that can be explained by the configuration. The consistency and overall coverage of the three configurations for high innovation performance in small-scale firms and the six configurations for large-scale firms are above the standard of 0.9, indicating that the selected configurations effectively explain the sources and conditions for high innovation performance in firms.

High innovation performance path for small-scale firms

In Table 10, S1-S3 represent the three configurations of high innovation performance in small-scale firms. Considering that there are numerous cases where contributing conditions related to firm characteristics are absent in all three paths, this discussion focuses on the four indicators of employee incentives and the centra conditions.

Based on configuration S1, it is possible to achieve high innovation performance in small-scale firms even in the absence of all causal conditions. Among them, the absence of growth, HHI, Mshare, and FOPG are identified as centra conditions for enhancing performance, while the absence of other causal variables serves as contributing conditions. Configuration S1 also suggests that emerging and less powerful firms have the potential to achieve high innovation performance, provided that they choose to enter competitive industries rather than industries dominated by large firms and avoid blind expansion. Furthermore, the management team should not be lured away by industry tournaments but should be retained through relatively higher pay. If there is insufficient managerial equity, firms may finance high-quality innovation activities at the cost of diluting their own shares.

Configuration S2 identifies the presence of FMPG and the absence of FIPG and FOPG as centrosome conditions. This indicates that small-scale firms can motivate their management team to achieve high innovation performance by increasing the pay gap within the management team. However, this configuration also requires reducing the pay gap between employees and the management team as well as the pay gap between the management team of the focal firm and the highest-paid management team in the same industry. The former may be aimed at maintaining a sense of fairness among the firm’s ordinary employees, while the latter may be aimed at retaining the firm’s management team through lucrative pay.

Configuration S3 identifies the presence of Mshare and the absence of Growth, Age, and HHI as centra conditions. Unlike in the previous configurations, this path indicates that small-scale firms can achieve high innovation performance by setting managerial shares as a centra condition and considering the three types of pay gaps as contributing conditions. Additionally, the absence of firm age as a centra condition in this configuration suggests that this path is particularly suitable for emerging small-scale firms. In terms of applicability, this configuration type has the highest coverage among small-scale firms, indicating that it is the most common form for achieving high innovation performance in this context.

High innovation performance path for large-scale firms

Table 10, L1–L4, represent the six configurations of high innovation performance in large-scale firms, indicating that the paths to achieving high innovation performance are more complex for large-scale firms. Based on the presence and absence of centra conditions, this study categorizes the configurations into three types and focuses on discussing the centra conditions of the configurations, similar to small-scale firms.

Configurations L1a, L1b, and L1c all have the presence of FOPG, Mshare, and Board were present as centra conditions. This finding suggests that one type of high innovation path for large-scale firms relies on high managerial pay, equity holdings, and complex organizational structures. The reason may be that although the organizational complexity of these firms is high, it is efficient and facilitates the transmission of goals and intentions from top to bottom. Firms can motivate their employees by incentivizing managers, leading to innovation activities. Comparing these three configurations, configuration L1a includes the presence of an internal managerial pay gap and the absence of industry concentration and firm age as contributing conditions, while configuration L1b includes the presence of internal and external pay gaps, firm age, and the absence of industry concentration as contributing conditions. This indicates that in competitive industries, well-established large firms are inclined to increase the pay gap between ordinary employees and managers to motivate innovation activities. On the other hand, younger large firms need to provide higher pay to ordinary employees to achieve innovation goals. Configuration L1c is more suitable for large firms operating in highly concentrated industries where the absence of internal and external pay gaps serves as contributing conditions, indicating that large firms in monopolistic environments can achieve high innovation performance even without relying on these two types of pay gaps.

Configurations L2a and L2b have the presence of FIPG and FOPG were present, and the absence of Age as centra conditions. This indicates that for some emerging large-scale firms, increasing the pay gap between ordinary employees and managers while setting relatively low pay for the focal firm’s management team is conducive to achieving high innovation performance. The reason may be that in emerging firms, employees are willing to accept a larger pay gap and relatively lower salaries because they anticipate future pay growth (with the presence of growth as a contributing condition) or the opportunity to switch to higher-paying firms after achieving certain accomplishments. The difference between the two configurations lies in configuration L2a being more inclined to exist in competitive industries, where the absence of FMPG serves as a contributing condition, while the presence of managerial equity serves as a contributing condition. Conversely, Configuration L2b is more inclined to exist in relatively monopolistic industries, where the presence of FMPG serves as a contributing condition, while the absence of managerial equity serves as a contributing condition. This difference may be attributed to the level of competition in the industry influencing employees’ expectations. A high level of competition is suitable for reducing agency problems through managerial equity, thus better promoting the firm’s survival and development, while a low level of competition is suitable for firms outsourcing equity to gain more resources and maintain their monopoly position.

Configuration L3 has the presence of FIPG and Mshare and the absence of Growth as centra conditions. The presence of FIPG indicates a significant gap in pay between ordinary employees and the management team, while the absence of FOPG suggests that the average pay of the management team is relatively low within the industry. This implies that the firm has lower costs in terms of employee pay. Additionally, the absence of sales growth suggests that the firm allocates a significant amount of resources to research and development rather than to expansion. The presence of Mshare indicates that the firm incentivizes the management team by sharing future research and development benefits with them.

Finally, after conducting robustness tests using the same set of firms in 2016 and 2018 as samples, we found that the above paths were consistently present. This indicates a certain level of robustness and generalizability in the results.

Conclusion, discussion, and limitations

Conclusion

We deduce the potential nonlinear impact of pay gaps on firm innovation by combining the tournament effect and the social comparison effect. Empirical research was conducted using panel data from Chinese A-share listed companies from 2009 to 2019. The results reveal the following findings: The influence of the internal pay gap and the pay gap in management on firm innovation output exhibit a concentrated inverted U-shaped curve, with the inflection point occurring before the peak. Due to the weaker tournament effect, the impact of the external pay gap on firm innovation follows a complete inverted U shape. Furthermore, the study also finds that the internal pay gap is more sensitive to low-quality innovation, while the external pay gap and the pay gap in management are more sensitive to high-quality innovation. Finally, the business strategy, ownership, and competitive position of firms all have an impact on the aforementioned relationships. The empirical results are summarized in Fig. 4, illustrating the key findings.

After demonstrating that the impact of pay gaps on firm innovation is contingent upon various internal and external factors, we used the fsQCA to explore which combinations of pay gaps and other internal and external factors constitute necessary conditions for high firm innovation performance.

In general, small-scale firms are suitable for engaging in innovation activities in competitive industries with simple organizational structures. They can adopt different paths to stimulate innovation: The management pay incentive path (Configuration S1) involves forgoing management shareholding and using higher industry pay to motivate the management team to innovate. The internal tournament incentive path (Configuration S2) emphasizes maintaining higher pay for both regular employees and the management team while widening the pay gap within the management team. The employee tournament incentive path (Configuration S3) involves adopting a management shareholding model and widening the pay gap among employees at different levels to incentivize all employees to innovate. Regarding the relationships between the conditional variables, small-scale firms that opt for management shareholding can widen the pay gap among employees at different levels, while those without management shareholding need to provide relatively higher pay to employees at all levels.

The path to high firm innovation performance in large-scale firms is more complex. There are different paths for stimulating innovation: The management equity incentive path (Configuration L1) involves establishing a large board of directors and offering low salaries but equity to the management team. A low pay and maintain firm growth path (Configuration L2) is suitable for young firms, where the focus is on maintaining business growth, widening the internal pay gap, and providing lower pay to all employees. The management pay and equity incentive path (Configuration L3) entails offering higher salaries to the management team, widening the pay gap among employees at different levels, and forgoing business expansion while retaining management shareholding.

Moreover, in terms of the relationships between the conditional variables, competitive industries and young large-scale firms are more inclined to stimulate high firm innovation performance by widening the pay gap among employees. On the other hand, monopolistic industries are better suited for incentivizing management teams by sharing equity and future benefits.

Discussion

Previous studies have predominantly focused on a singular type of pay gap, often positing a positive correlation with firm innovation (e.g., Banker et al., 2016; Coles et al., 2018; Pan and Yi, 2023). Expanding upon these studies, our research contributes several theoretical implications.

Firstly, our research challenges the conventional understanding of the impact of the pay gap on firm innovation, suggesting that the relationship is not a simple linear positive correlation dominated by the tournament effect. Instead, it reveals a potential inverted U-shaped relationship under the joint influence of various effects. However, to some extent, some of our empirical results align with previous research. For instance, the internal pay gap within firms positively motivates firm innovation (Pan and Yi, 2023; Miao et al., 2020). The difference is that we contend that this positive motivational effect diminishes as the pay gap expands, and this relationship is contingent on additional moderating factors.

Secondly, we simultaneously introduce three types of pay gaps and extensively analyze how the aforementioned relationship is constrained and moderated by factors at the organizational and industry levels. This deepens our understanding of the causal mechanisms by which the pay gap affects the process of firm innovation. Furthermore, it serves as an integration, comparison, and in-depth exploration in relation to similar studies in the past.

Thirdly, our research makes significant contributions to the literature on factors influencing firm innovation and the literature on employee behavior. We posit that the motivational impact of pay gap on employees is not an isolated phenomenon but rather intricately linked to employees’ perceptions of their advancement opportunities (Moosa and Coetzee, 2020). The effectiveness of pay gap in stimulating innovation is contingent upon employees perceiving promotions as fair and viable opportunities. This elucidates why the motivation for innovation varies in strength between different pay gaps, ultimately transforming into a negative impact (Sun et al., 2023).

Moreover, our research, particularly in the section on heterogeneity analysis, brings about rich managerial implications.

Firstly, our research supports a close association between top executives in firms and high-quality innovation compared to low-quality innovation. We encourage fostering this connection and propose that the goals and expectations of executives should be further aligned with generating high-quality innovations that bring significant market value, as opposed to pursuing numerous low-value innovations.

Secondly, our study reveals that in state-owned firms, the impact of the pay gap on firm innovation is not significant. This provides a basis for the Chinese government’s restrictions on executive pay in state-owned enterprises (proposed in the introduction), ensuring fair compensation without hindering innovation activities. For firm owners, our recommendation is not to blindly pursue wage equality but to ensure incentive and promotion rewards for personnel engaged in innovation.

Additionally, our research uncovers a negative moderating effect of firm competitive positioning, where employees in highly competitive firms experience increased complexity in their demands. This necessitates owners to provide a more comprehensive care package for employees beyond just compensation. In other words, in companies with high competitive standings, motivating employees for innovation requires greater attention from organizational managers, given the widely acknowledged difficulty in promotions. A relevant study can provide similar examples; employees value financial rewards (benefits, performance and recognition, remuneration, career) as well as opportunities for career development, learning, and a balance between work and life (Bussin et al., 2017).

Finally, we employed fsQCA to offer insights for firm managers in setting appropriate compensation systems (S1-L3). This challenges the idea of adopting a one-size-fits-all approach in emulating the compensation structures of star firms. Due to notable differences in the characteristics of these firms compared to star firms, such as variations in company size, age, and the industry competition they encounter, compensation structures that work well for star firms may not produce significant effects within these imitators. Additionally, we advocate for the comprehensive consideration of both internal and external factors when designing compensation systems, rather than concentrating solely on a few factors.

In summary, our study aims to emphasize a crucial point: firms need to establish pay structures that align with their own strategies based on factors such as their own status, positioning, and external environment. Blindly replicating the pay structures of other firms may not be a prudent choice.

Limitations and future research

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, due to data availability constraints, we did not encompass a broader range of factors that could potentially influence the relationship between pay gap and innovation. For instance, some personal experiences of employees and the educational levels of employees were not considered. Secondly, while we attempted to use various instrumental variables to mitigate endogeneity, the development of more robust instrumental variables, especially those independent of innovation, is still needed. Lastly, constrained by data, our study did not delve into the detailed salary structures of company employees, such as the pay gap among research and development personnel.

Therefore, future research could construct more sophisticated measures of wage inequality among company employees and conduct in-depth investigations into the salary structures of specific groups, such as research and development or administrative staff. Additionally, focusing on the long-term impact of pay gap on innovation or its influence on sustainable innovation is an area worthy of attention. Addressing the challenge of ensuring sustained innovation in the face of employee mobility is a crucial aspect that merits further exploration.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary document. And related codes are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Acemoglu D, Restrepo P (2022) Tasks, automation, and the rise in us wage inequality. Econometrica 90(5):1973–2016

Acemoglu D, Akcigit U, Celik MA (2022) Radical and incremental innovation: the roles of firms, managers, and innovators. Am Econ J: Macroecon 14(3):199–249

Akerman A, Helpman E, Itskhoki O, Muendler MA, Redding S (2013) Sources of wage inequality. Am Econ Rev 103(3):214–219

Autor DH, Katz LF, Kearney MS (2008) Trends in US wage inequality: revising the revisionists. Rev Econ Stat 90(2):300–323

Banker RD, Bu D, Mehta MN (2016) Pay gap and performance in China. Abacus 52(3):501–531

Brown V C, Evans III JH, Moser V D, Presslee A (2022) The strength of performance incentives, pay dispersion, and lower-paid employee effort. J Manag Account Res 34(3):59–76

Bussin MH, Pregnolato M, Schlechter AF (2017) Total rewards that retain: a study of demographic preferences. SA J Hum Resour Manag 15(1):1–10

Buttrick NR, Oishi S (2017) The psychological consequences of income inequality. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 11(3):e12304

Chen Q, Lin S, Zhang X (2020) Chinese technology innovation incentive policies: incentivizing quantity or quality. China Ind Econ 385:79–96