Abstract

This paper provides a simple political economy model of hierarchical education to study the endogenous determination of the public education budget and its allocation between different tiers of education (basic and advanced). The model integrates private education decisions by allowing parents, who are differentiated according to income and human capital, to opt out of the public system and enrol their offspring at private universities. Majority voting decides the size of the budget allocated to education and the expenditure composition. The model exhibits a potential for multiple equilibria and ‘low education’ traps. Income inequality and the intergenerational persistence of educational attainments play a fundamental role in deciding the equilibrium. The main predictions of the theory are broadly consistent with descriptive cross-country evidence collected for 43 high-middle income countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, see Fernandez and Rogerson (1995), Epple and Romano (1996), Beviá and Iturbe-Ormaetxe (2002), Levy (2005), De la Croix and Doepke (2009), Gradstein et al (2004), Di Gioacchino and Sabani (2009), Haupt (2012), Arcalean and Schiopu (2016), Lasraman and Laussel (2019) and Hatsor and Zilcha (2021).

See Glomm and Ravikumar (1992, 2003). Empirical evidence has demonstrated that even when education fully relies on public funding, children from families with a lower socioeconomic status have lower enrolment rates at higher levels of education. See De Fraja (2004) and Cunha and Heckman (2007). See Lagravinese et al. (2020) for recent evidence on the effect of economic, social and cultural status on educational performance.

See Aina et al. (2021) for a review of the socioeconomic literature on drop-out rates.

The literature has also emphasised the influence of the structure of the educational system (e.g. the selection pattern) on the intergenerational educational persistence (see Chusseau and Hellier 2011 and references cited therein). Specifically, the institutional characteristics of the school system, such as formal differentiation (students are separated by ability through early tracking) and/or informal differentiation (socioeconomic segregation among schools), have a strong impact on the formation and the persistence of social segmentation (Shavit and Muller 2000 and Kerckhoff 2000).

As reported by Dynarski and Scott-Clayton (2016), in 2015 US households received $19.7 billion in tax credits, which are just one of the many tax subsidies for private education. In the EU, tax incentives for education expenses, including income tax credit in some countries, are widely available (Cedefop 2009).

In Di Gioacchino et al (2022) parents cannot opt out of the public system, but they can top up public spending with private expenditure.

Although, a political equilibrium with a multidimensional policy might not exist (Persson and Tabellini 2000), in our model, we are able to characterise the political equilibrium in a majority voting framework.

For a classification of education models elaborated applying a cluster analysis on OECD countries, see Di Gioacchino et al. (2022).

See Lülfesmann and Myers (2011) on this point. They argue that the quality of public goods might not be positively related to opting out decisions (through decongestion effects) when adverse selection imposes negative externalities on public users. This argument is valid above all in applications such as education and health.

We do not address fertility decisions in this model, although we are aware of the trade-off between quantity and quality when choosing to bear children.

This assumption is consistent with the idea of efficiency units of labour.

Income consists of a general consumption good that serves as the numeraire.

We select a uniform distribution of income for analytical tractability. We are aware that under majority voting the standard Meltzer and Richard (1981) redistribution issue disappears. As we later discuss, in our model, the effect of income inequality on public education budget does not depend on the distance between median and average income, but on the parameter \(\delta .\)

A sure-return linear storage technology exists which earns a gross return equal to 1 for each unit of income saved.

Assuming a double-log utility function implies that the elasticity of the marginal utility of the two “goods” is constant and equal to one.

We assume that access to tertiary education is universal, but the probability of drop** out of college is influenced by parental human capital. Results would not change by introducing non-universal university access and assuming that the access probability were dependent on parental human capital as well.

To have a share of graduate parents that does not change over time (stationary state) and remains less than 1, we would need to introduce a positive rate of drop** out for children of graduate parents; however, assuming a drop** out probability equal to zero for children of graduate parents allows for a simpler notation without changing qualitative results.

This tax represents the incremental impact of public education financing needs on the overall tax system.

We assume that education expenditure can be entirely deducted from the income tax base. This assumption simplifies the analysis without affecting qualitative results.

The literature on hierarchical education has modelled the human capital accumulation assuming different production functions, which substantially differ for the degree of substitutability/complementarity between the two education stages. In Su (2004 and 2006), Romero (2012) and Naito and Nishita (2017), the human capital of a tertiary graduate student is given by the sum of basic and advanced education. Differently, in Arcalean and Schiopu (2010), Viane and Zilcha (2013), Chusseau and Hellier (2011) and Sarid (2017), advanced education adds to basic education in a multiplicative way. Other differences in the assumed human capital production function refer to whether or not basic and/or advanced education depend on family background (e.g. parental education) and on whether or not to access advanced studies a minimum level of basic education is required.

If \({h}_{T}=0\) (which can happen in equilibrium), then I = 0 and \(\mathit{EU}\left(c,{h}_{B},{h}_{T}\right)=\mathit{ln}(c)+\gamma \mathit{ln}\left({h}_{B}\right)\).

Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner (2008) have shown that parental background has an impact on students’ academic achievements per se, regardless of the effect of family financial conditions This does not rule out the importance of the lack of financial resources to pay for the (monetary) costs of tertiary education. For example, Goldthorpe (2003) writes -citing research in Sweden and Britain-that among children of average ability those from higher salaried class origin are almost twice more likely to opt for academic courses than those from working class origins. However, when tuition fees are related to family income, like in the Italian university system, Aina (2005) has found that household economic conditions do not affect dropout rates, but academic persistence is positively correlated with parental education.

See among others Smith and Naylor (2001), Johnes and McNabb (2004), Di Pietro and Cutillo (2008), Gury (2011), Aina (2013), Ghignoni (2017). All these contributions have shown for different countries that parental education is positively related to students’ performance at university, and negatively related to the probability of drop** out.

The same assumption made for the first stage of education is innocuous as all children participate in public education and thus public spending per capita and total public spending coincide.

We follow De la Croix and Doepke (2009) in the specification of the timing of decisions. Such timing is motivated by the observation that public education spending can be adjusted more frequently than the choice between public vs. private education, which might entail substantial switching costs.

If \(x=\widehat{x}({G}_{T}^{e},{h}_{p}, \pi)\), we assume that households opt out of the public system.

Assumption 1(i) is introduced to simplify the analysis of the voting game and it is justified by the fact that non-graduate parents have a higher opportunity cost of enroling their children at private universities and a lower average income. Relaxing Assumption 1(i) and allowing some non-graduate parents to enrol their children at private universities would not change qualitative results.

Note that if the expected outcome of the voting process is such that the equilibrium level of public tertiary spending is not effective (\({G}_{T}^{e}<1\)), children of non-graduates and of those graduates not opting out will not attend university.

We introduce the new notation \(\widetilde{x}\) for the income threshold level that separates public and private university pupils because \(\widetilde{x}\) and \(\widehat{x}\) do not exactly coincide: when \(\widehat{x}>m+\delta \), \(\widetilde{x}= m+\delta \) and when \(\widehat{x}<m-\delta , \widetilde{x}= m-\delta .\)

If this were not the case, there would be some values of \({G}_{T}^{e}\) such that the public budget would not be high enough to allow an effective public tertiary investment and therefore agents would maximise an expected utility function obtained from Eq. (6) setting I = 0.

As it will be shown below (see Proposition 1), this parameters’ restriction is important to assure the existence of at least one fixed point with an effective level of tertiary education spending for each \(P\in \left\{A,B\right\}\). The parameter set satisfying this restriction is nonempty, as it is demonstrated in the numerical examples in Sect. 4.

Note that, within groups, \({\tau }^{P}\) does not depend on income. This is a consequence of having assumed a logarithmic utility function as the elasticity of marginal utility of consumption is equal to 1. Between groups, the redistributive conflict depends on the different expected benefits from public education.

In fact, since group A is the median in both dimensions, \(\left({{\tau }^{A}, \phi }^{A}\right)\) wins in pairwise comparisons against \(\left({{\tau }^{B}, \phi }^{B}\right)\) and against \(\left({{\tau }^{C}, \phi }^{C}\right)\). Note that also a coalition between groups B and C, proposing a linear combination between the groups’ bliss points \(\left({{\tau }^{BC}, \phi }^{BC}\right)\), would be defeated by \(\left({{\tau }^{A}, \phi }^{A}\right)\) because this policy-pair would be preferred to \(\left({{\tau }^{BC}, \phi }^{BC}\right)\) by either group B or C. The same voting outcome would have been obtained assuming issue by issue voting as in Shepsle’s (1979) structure induced equilibrium (see Persson and Tabellini 2000).

A focal point (or Schelling point) is a solution that economic agents tend to choose by default in the absence of communication (see Shelling 1960).

Specifically, this result depends on our assumption about the human capital production function in expression (4). If variable costs were more important than fixed costs in the production of tertiary education, or if adverse selection, due to peer group effects, did not affect negatively the quality of public education, an increase in the share of population opting out of the public system might rise the welfare of public users. Indeed, in De la Croix and Doepke (2009) the result that an increase in inequality improves the welfare of “poor” agents depends on assuming constant return to scale in the human capital production function and on abstracting from adverse selection effects.

Analogous graphs can be obtained changing \(\delta \) for group B.

Note that the condition \({\widehat{x }({G}_{T}^{*P})}^{2}>{m}^{2}-{\delta }^{2}\) is always satisfied in our numerical examples. Thus, the budget decreases as income inequality increases.

This result is confirmed by Dragomirescu-Gaina et al. (2015)’s empirical analysis. They focus on Europe and highlight the growing divide between the best and the low-performing countries in terms of tertiary educational attainment. Their calculations show a slower expected progress for lagging countries and a faster expected progress for high-performing countries.

We thank an anonymous referee for the suggestion.

See Persson and Tabellini (2000) and references therein.

See for example Di Pietro and Cutillo (2008) for a discussion of the effect on drop-out rates of the 2001 Italian reform of tertiary education.

Note that, \(\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)={\text{max}}\left(m-\delta ; \frac{{\left(1+ \gamma \right)}^{\frac{1+ \gamma }{\gamma }}}{ \gamma }\right)\) when \(0\le {G}_{T}^{e}\le 1\).

Being \({\Delta }^{P}({G}_{T }^{e})\) a monotone transformation of the budget function F, its continuity and monotonicity follows from continuity and monotonicity of F (see eq. A.1).

By utilizing the same argument as in the case (i), we can exclude the existence of more than three fixed points.

In the case of Ireland, expenditures are computed as a share of gross national income (GNI) as GDP is not a satisfactory measure of country’s income due to large income outflow.

Based on ISCED 2011, public basic K-12 refers to educational levels 1 up to 4; public tertiary refers to levels 5 up to 8; total private and total public refer to educational levels 1 up to 8.

For OECD countries and Russian Federation data on public and private spending on education are taken from OECD (2023a, 2023b), and OECD Education at a Glance Publications from 2003 to 2010. Private spending is not available in at least one of the two decades for Luxembourg, Switzerland, and Costa Rica, therefore they are not included in the sample. For non-OECD countries data on education spending are taken from UNESCO, UIS database. As regard to private spending, data are taken from the Sustainable Development Goal 4.5.4. We derive the share of private spending on GDP from the expenditure per student in PPP dollars.

A similar approach is followed by De la Croix and Doepke (2009).

As discussed in Sect. 3, in our model, income inequality only affects the public budget through the tax deductibility of private expenses, which are decided based on perfectly foresighted public expenses. For this reason, in the correlations, we use the Gini index computed for disposable income. For OECD countries, except for Colombia, the source is the Income Distribution Database available at https://stats.oecd.org/. For non-OECD countries the reference is the Gini Index of the World Bank available at https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=SI.POV.GINI

COR measures intergenerational persistence in education using Pearson’s correlation coefficient between parents’ and children’s years of education. In the GDIM (WB 2023a, 2023b), data are available for different cohorts; the 1980s (1970s) cohort refers to the generation born between 1980 (1970) and 1989 (1979) and their parents. For parents’ educational attainment, we take the subpopulation ‘max’, which represents the greatest available values among parents. For children’s educational attainment, we consider ‘all’ the respondents who belong to the cohort.

We derive it from the Penn World Tables and take the log of the average over the years 1990 to 1999 and 2000 to 2009 for the first and the second period, respectively (Feenstra et al. 2015, https://doi.org/10.34894/QT5BCC).

For brevity, we do not report results for total public expenditure, since we focus on its composition. They are available upon request from authors.

One objection would be that the rich may send their children overseas for private education. Looking at the outbound mobility ratio, which is the ‘number of students from a given country studying abroad, expressed as a percentage of total tertiary enrolment in that country’, in 2019 Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Turkey had very low mobility in comparison to the other countries in our sample (UNESCO Institute for Statistics (http://data.uis.unesco.org/)).

References

Aina C (2005) Parental background and college drop-out. Evidence from Italy. In: EPUNet-2005 Conference, Colchester, Institute for Social and Economic Research

Aina C (2013) Parental background and university dropout in Italy. High Educ 65(4):437–456

Aina C, Baici E, Casalone G, Pastore F (2021) The determinants of university drop-out: A review of the socio-economic literature. Socio-Econ Plann Sci 79:101102

Arcalean C, Schiopu I (2010) Public versus private investment and growth in a hierarchical education system. J Econ Dyn Control 34(4):604–622

Arcalean C, Schiopu I (2016) Inequality, opting-out and public education funding. Soc Choice Welf 46(4):811–837

Bandiera O, Larcinese V, Imran I (2009) Heterogeneous class size effects: new evidence from a panel of university students. C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers: # 7512

Beviá C, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I (2002) Redistribution and subsidies for higher education. Scand J Econ 104(2):325–344

Blankenau W, Cassou S, Ingram B (2007) Allocating government education expenditures across K-12 and college education. Econ Theor 31(1):85–112

Brinkman PT, Leslie LL (1986) Economies of scale in higher education; sixty years of research. Rev Higher Educ 10(1):1–28

Cedefop (2009) Using tax incentives to promote education and training. Publications Office, Luxembourg

Chusseau N, Hellier J (2011) Educational Systems, Intergenerational Mobility and Social Segmentation. Eur J Comp Econ 8(2):203–233

Cohn E, Rhine SLW, Santos MC (1989) Institutions of higher education as multi-product firms: economies of scale and scope. Rev Econ Stat 71:284–290

Cunha F, Heckman J (2007) The technology of skill formation. Am Econ Rev 97(2):31–47

De Fraja G (2004) Education and Redistribution. Rivista Di Politica Economica V–VI:3–44

De Groot H, McMahon W, Volkwein JF (1991) The cost structure of American Research Universities. Rev Econ Stat 73(3):424–431

De La Croix D, Doepke M (2009) To segregate or to integrate: education politics and democracy. Rev Econ Stud 76(2):597–628

Di Gioacchino D, Sabani L (2009) Education policy and inequality: a political economy approach. Eur J Polit Econ 25(4):463–478

Di Gioacchino D, Sabani L, Tedeschi S (2019) Individual preferences for public education spending: does personal income matter? Econ Model 82:211–228

Di Gioacchino D, Sabani L, Usai S (2022) Intergenerational Upward (Im)mobility and political support of public education spending. Ital Econ J 8(1):49–76

Di Pietro G, Cutillo A (2008) Degree flexibility and university drop-out: the Italian experience. Econ Educ Rev 27(5):546–555

Dragomirescu-Gaina C, Elia L, Weber A (2015) A fast-forward look at tertiary education attainment in Europe 2020. J Policy Model 37(5):804–819

Dynarski S, Scott-Clayton J (2016) Tax benefits for college attendance NBER Working Paper No. 22127

Epple D, Romano RE (1996) Ends against the middle: determining public services provision when there are private alternatives. J Public Econ 62(3):297–325

Feenstra RC, Inklaar R, Timmer MP (2015) The next generation of the penn world table. Am Econ Rev 105(10):3150–3182. https://doi.org/10.34894/QT5BCC

Fernandez R, Rogerson R (1995) On the political economy of education subsidies. Rev Econ Stud LXII:249–262

Ghignoni E (2017) Family background and university dropouts during the crisis: the case of Italy. High Educ 73(1):127–151

Glomm G, Ravikumar B (1992) Public versus private investment in human capital: endogenous growth and income inequality. J Polit Econ 100(4):818–834

Glomm G, Ravikumar B (2003) Public education and income inequality. Eur J Polit Econ 19(2):289–300

Glomm G, Ravikumar B, Schiopu IC (2011) The political economy of education funding. Handb Econ Educ 4:615–680

Goldthorpe J (2003) The myth of education-based meritocracy. New Econ 10(4):234–239

Gradstein M, Justman M, Meier V (2004) The political economy of education. Implications for growth and inequality. MIT Press

Gury N (2011) Drop** out of higher education in France: a micro-economic approach using survival analysis. Educ Econ 19(1):51–64

Hatsor L, Zilcha I (2021) Subsidizing heterogeneous higher education systems. J Public Econ Theory 23(2):318–344

Haupt A (2012) The evolution of public spending on higher education in a democracy. Eur J Polit Econ 28(4):557–573

Hill MC (1998) Class size and student performance in introductory accounting courses: further evidence. Issues Account Educ 13:47–64

ISSP (2006) International Social Survey Programme. Available at https://www.gesis.org/en/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/role-of-government/2006

Johnes G, McNabb R (2004) Never give up on the good times: student attrition in the UK. Oxf Bull Stat 66(1):23–48

Johnes G, Schwarzenberger A (2011) Differences in cost structure and the evaluation of efficiency: the case of German universities. Educ Econ 19(5):487–499

Kennedy PE, Siegfried JJ (1997) Class size and achievement in introductory economics: evidence from TUCE III data. Econ Educ Rev 16:385–394

Kerckhoff AC (2000) Transition from school to work in comparative perspective. Handbook of the sociology of education. Springer, pp 453–474

Lagravinese R, Liberati P, Resce G (2020) The impact of economic, social and cultural conditions on educational attainments. J Policy Model 42(1):112–132

Lasram H, Laussel D (2019) The determination of public tuition fees in a mixed education system: a majority voting model. J Public Econ Theory 21(6):1056–1073

Levy G (2004) A model of political parties. J Econ Theory 115(2):250–277

Levy G (2005) The politics of public provision of education. Q J Econ 120(4):1507–1534

Lülfesmann C, Myers GM (2011) Two-tier public provision: comparing public systems. J Public Econ 95:1263–1271

Machado MP, Vera-Hernandez M (2008) Does class-size affect the academic performance of first year college students? University College London, Mimeo

Meltzer AH, Richard SF (1981) A rational theory of the size of government. J Polit Econ 89(5):914–927

Naito K, Nishida K (2017) Multistage public education, voting, and income distribution. J Econ 120(1):65–78

OECD (2023a) Education at a glance, various years: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris

OECD (2023b) Public spending on education (indicator). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/f99b45d0-en

OECD (2023c) Private spending on education (indicator). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/6e70bede-en

OECD (2003d) Education at a Glance 2003: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2003-en

OECD (2004) Education at a Glance 2004: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2004-en

OECD (2005) Education at a Glance 2005: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2005-en

OECD (2006) Education at a Glance 2006: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2006-en

OECD (2007) Education at a Glance 2007: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2007-en

OECD (2008) Education at a Glance 2008: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2008-en

OECD (2009) Education at a Glance 2009: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2009-en

OECD (2010) Education at a Glance 2010: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2010-en

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political Economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press

Restuccia D, Urrutia C (2004) Intergenerational persistence of earnings: the role of early and college education. Am Econ Rev 94(5):1354–1378

Romero G (2012) Determining public provision of education services in a sequential education process. BE J Econ Anal Policy 12(1):1–42

Sarid A (2017) Public investment in a hierarchical educational system with capital-skill complementarity. Macroecon Dyn 21(3):757–784

Shavit Y, Muller W (2000) Vocational secondary education. Eur Soc 2(1):29–50

Shelling T (1960) The strategy of conflict. Harvard University Press

Shepsle K (1979) Institutional arrangements and equilibrium in multidimensional voting models. Am J Polit Sci 23(1):27–59

Smith JP, Naylor RA (2001) Drop** out of university: A statistical analysis of the probability of withdrawal for UK university students. J R Stat Soc A Stat Soc 164(2):389–405

Stinebrickner T, Stinebrickner R (2008) The effect of credit constraints on the college drop-out decision: a direct approach using a new panel survey. Am Econ Rev 98(5):2163–2184

Su X (2004) The allocation of public funds in a hierarchical educational system. J Econ Dyn Control 28(12):2485–2510

Su X (2006) Endogenous determination of public budget allocation across education stages. J Dev Econ 81(2):438–456

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) database (2023) http://data.uis.unesco.org

Viane JM, Zilcha I (2013) Public funding of higher education. J Public Econ 108:78–89

Worthington AC, Higgs H (2011) Economies of scale and scope in Australian higher education. High Educ 61:387–414

World Bank (2023a) Global database on intergenerational mobility. World Bank Group, Washington D.C.

World Bank (2023b) World development indicators. World Bank

World Bank, Gini Index (World Bank estimate). https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI

Funding

This study was not funded by external sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Lemma 1.

There exists a threshold:

such that households, whose human capital is \({h}_{p},\) strictly prefer private education if and only if \(x>\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e},{h}_{p},\pi \right)\).

Proof.

If the household is planning to choose public tertiary education, the expected utility is given by Eq. (6) substituting \({h}_{T}={G}_{T}^{e}\)

with I = 0 for \({G}_{T}^{e}<1\) and I = 1 for \({G}_{T}^{e}\ge 1 .\)

The expected utility of the opting out decision is instead given by Eq. (6) setting \({h}_{T}={e}^{*}\)

Imposing\(EU\left({c,{h}_{B} , G}_{T}^{e}\right)=EU\left(c,{h}_{B},{e}^{*}\right)\), we obtain the threshold in Eq. (10).

Lemma 2.

The public budget \({\text{F}}\left(\uptau ,{{\text{G}}}_{{\text{T}}}^{{\text{e}}};\updelta ,{\text{K}}\right)\) satisfies the following:

-

(i)

\(\frac{\partial F}{{\partial \tau }} > 0\)

-

(ii)

\(\frac{\partial F}{{\partial G_{T}^{e} }} \ge 0\).

-

(iii)

\(\frac{\partial F}{{\partial \delta }} \le 0\; if \; \hat{x}\left( {G_{T}^{e} } \right)^{2} > m^{2} - \delta ^{2}\).

-

(iv)

\(\frac{\partial F}{{\partial K}} > 0\; if h < \frac{1}{{\left( {1 + \gamma } \right)}}\).

Proof.

Substituting Eq. (11) into Eq. (13), we obtain the following expression for the budget for \({G}_{T}^{e}\ge 0\):

(i) It is straightforward. (ii) The rate of opting out decreases with \({G}_{T}^{e}\) (\(\frac{\partial \widehat{x}}{\partial {G}_{T}^{e}}\ge 0)\). This implies that the level of private expenditures in tertiary education (which are tax deductible) decreases with \({G}_{T}^{e}\). (iii) Taking the first derivative of the budget in eq. (A.1) with respect to \(\updelta \), when \(m-\delta <\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)<m+\delta ,\) it is easy to show that it if \({\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)}^{2}>{m}^{2}-{\delta }^{2}\) the derivative is negative. In the other cases, \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial\updelta }=0.\) (iv) The average income \(M=\left(1-K\right)hm+Km\) is positively related to K, thus, from A.1 we obtain:

Noting that \(\tau \left[m\left(1-h\right)-\frac{\gamma }{4\delta (1+\gamma )}\left({\left(m+\delta \right)}^{2}-{\left(\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)\right)}^{2}\right)\right]<\tau m\left[1-h-\frac{\gamma }{(1+\gamma )}\right]\), \(\forall {G}_{T }^{e}\ge 0\), a sufficient condition for \(\frac{\partial F}{\partial K}>0\) is \(h<\frac{1}{(1+\gamma )}\)<1.

Lemma 3.

For \({{P}}\in \left\{{{A}},{{B}}\right\}\) and \(\forall\; {{\text{G}}}_{{\text{T}}}^{{\text{e}}}\ge 0\), the fiscal room is enough to guarantee that \({{\text{G}}}_{{\text{T}}}^{{\text{P}}}>1\) if

Proof.

The above condition is obtained from A.1 by considering its minimum value and \(\tau \) preferred by group A.Footnote 47 Consequently, it holds a fortiori when the budget increases, and, given the ranking of the preferred policies in expression (14), it is satisfied a fortiori for \(P=B\).

Proof of Proposition 1.

For \(P\in \left\{A, B\right\}\), given parameters’ restriction in Lemma 3, \({\Delta }^{P}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)>1\) and it is continuous monotone nondecreasing in \({G}_{T}^{e}\) (see Lemma 2), with \({G}_{T}^{e}\in {\mathbb{R}}_{+}\).Footnote 48 Its minimum value is obtained for \(0\le {G}_{T}^{e}\le 1\)

The maximum value is obtained when \(\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)\ge m+\delta \). In this case, public tertiary education spending is equal to its maximum

There are two possibilities:

-

(i)

\({z}^{P}M<\frac{\gamma \left(m+\delta \right)}{{\left(1+ \gamma \right)}^{\frac{1+ \gamma }{\gamma }}}\)

-

(ii)

\({z}^{P}M\ge \frac{\gamma \left(m+\delta \right)}{{\left(1+ \gamma \right)}^{\frac{1+ \gamma }{\gamma }}}\)

First, we must show that the function \({\Delta }^{P}({G}_{T }^{e})\) crosses the 45-degree line exactly once when \({z}^{P}M<\frac{\gamma \left(m+\delta \right)}{{\left(1+ \gamma \right)}^{\frac{1+ \gamma }{\gamma }}}\). In this case, \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})< {G}_{T}^{e}\) when\({G}_{T}^{e}=\frac{\gamma \left(m+\delta \right)}{{\left(1+ \gamma \right)}^{\frac{1+ \gamma }{\gamma }}}\), while \({\Delta }^{P}\) (\({G}_{T}^{e})> {G}_{T}^{e}\) when\({0\le G}_{T}^{e}\le 1\). We can exclude that \({\Delta }^{P}({G}_{T }^{e})\) crosses more than once, as the relationship between the budget and \({G}_{T}^{e}\) is quadratic, and it is easy to verify that the first derivative of the function \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) with respect to \({G}_{T}^{e}\) is monotone nondecreasing. Therefore, \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) crosses the 45-degree line only once and the fixed point \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) lies in the interval \(1<{G}_{T}^{P*}<{z}^{P}M.\)

In case (ii), there is instead the possibility of triple crossing.Footnote 49\({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) certainly crosses the 45-degree line at \({G}_{T}^{e}=\) \({z}^{P}M\) and therefore the fixed point \({G}_{T}^{P*}={z}^{P}M\) always exists. The function might double cross below \({z}^{P}M\) and in this case, we might have two additional interior fixed points with 1 \(<{G}_{T}^{P*}<{z}^{P}M\).

For \(P=C,\) as \({\Delta }^{C}\left({G}_{T}^{e}\right)=0 \; \forall \; {G}_{T}^{e},\) there exists a unique fixed point \({G}_{T}^{C*}=0\) for \({G}_{T}^{e}=0\).

Proof of Proposition 2.

2.1 To prove that \({G}_{T}^{B*}>{G}_{T}^{A*}\) recall that \({z}^{B}>{z}^{A}\). When \({G}_{T}^{P*}={z}^{P}M\) the result is obvious. Suppose that \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) is an interior fixed point and consider the following implicit function Z:

As \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) is a solution of (A.2), by the implicit function theorem, we can write

Indeed, the numerator (\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial {z}^{P}})\) has negative sign. The denominator (\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial {G}_{T}^{P*}})\) has positive sign because, when \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) is an interior solution and a focal point, the function \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) has a positive slope smaller than 1 in \({G}_{T}^{P*}.\)

2.2 To prove that for \(P=A\) \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{A*}}{d\eta }>0\), we first note that \(\frac{d{z}^{A}}{d\eta }\)>0. Hence, the result is obvious when \({G}_{T}^{A*}={z}^{A}M.\) Suppose that \({G}_{T}^{A*}\) is an interior solution and consider the function (A.2). By the implicit function theorem, we can write:

The numerator (\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial\upeta })\) has negative sign for P = A. The denominator (\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial {G}_{T}^{P*}})\) has positive sign because, when \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) is an interior solution and a focal point, the function \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) has a positive slope smaller than 1 in \({G}_{T}^{P*}\); thus, \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{A*}}{d\eta }>0\).

2.3 Firstly, note that when \({G}_{T}^{P*}={z}^{P}M,\) \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{P*}}{d\delta }=0.\) Focusing on interior solutions, to prove that \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{P*}}{d\delta }\le 0\), iff \({\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{P*}\right)}^{2}\ge {m}^{2}-{\delta }^{2}\), consider the function (A.2). By the implicit function theorem, we can write

The numerator sign depends on the sign of the public budget derivative with respect to inequality. Therefore, from Lemma 2\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial \delta }>0\) iff \({\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{P*}\right)}^{2}>{m}^{2}-{\delta }^{2}\). The denominator (\(\frac{\partial Z}{\partial {G}_{T}^{P*}})\) has positive sign because, when \({G}_{T}^{P*}\) is an interior solution and a focal point the function \({{\Delta }^{P}(G}_{T}^{e})\) has a positive slope smaller than 1; thus, \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{P*}}{d\delta }<0\) iff \({\widehat{x}\left({G}_{T}^{P*}\right)}^{2}>{m}^{2}-{\delta }^{2}\)

2.4 Firstly, note that when \({G}_{T}^{P*}={z}^{P}M,\) \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{P*}}{dK}=0\). Focusing on interior solutions, to prove that \(\frac{d{G}_{T}^{P*}}{dK}>0\) if \(h<\frac{1}{(1+\gamma )}\) we have to consider the implicit function in A.2, the conditions stated in Lemma 2, and follow the same logical steps of the previous proofs.

Proof of Proposition 3.

Consider only focal fixed points.

3.1 For \(\left[{\tau }^{*}= {\tau }^{A},{ \phi }^{*}= {\phi }^{A}\right]\) to be a political equilibrium of the voting game, with \({{G}_{T}^{e}=G}_{T}^{A*}\), it must be \(\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\) (group C is not majoritarian), and \(1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\) (group B is not majoritarian). Recalling that the measure of group A does not depend on the opting out rate, if A is majoritarian (\(1-K>\frac{1}{2}\)), these two conditions are always satisfied for any \(1< {G}_{T}^{A*}\le {z}^{A}M\); thus, \(\left[{\tau }^{*}= {\tau }^{A},{ \phi }^{*}= {\phi }^{A}\right]\) is the unique political equilibrium.

3.2 From Proposition 1 and Proposition 2, \({G}_{T}^{C*}<{G}_{T}^{A*}<{G}_{T}^{B*}\) and \(\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{C*}\right)>\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)>\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{B*}\right)\). To show that at least one political equilibrium exists, note that if neither \(\left[{\tau }^{*}= {\tau }^{C}, {\phi }^{*}= {\phi }^{C}\right]\) nor \(\left[{\tau }^{*}= {\tau }^{B},{ \phi }^{*}= {\phi }^{B}\right]\) are political equilibria, that is if \(1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{B*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\; {\text{and}}\; \Omega \left({G}_{T}^{C*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K},\) then \(\left[{\tau }^{*}= {\tau }^{A},{ \phi }^{*}= {\phi }^{A}\right]\) is certainly a political equilibrium with \({{G}_{T}^{e}=G}_{T}^{A*}\). In fact,\(1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{B*} \right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\) implies \(1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)<\frac{1}{2K}\) (group B is not majoritarian); whereas \(\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{C*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\) implies \(\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)<\frac{1}{2K}\) (group C is not majoritarian). In this political equilibrium, group A is pivotal, although not majoritarian (see preferred policies ranking in expression (14) in the text).

To show that a multiplicity of political equilibria might arise, note that for the fixed points \({{G}_{T}^{A*},{G}_{T}^{B*},G}_{T}^{C*}\) to be associated with political equilibria the following conditions must be satisfied:

\(\left(i\right) 1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\; {\text{and}} \; \Omega \left({G}_{T}^{A*}\right)\le \frac{1}{2K}\) for \({G}_{T}^{A*};\)

\(\left(ii\right) 1-\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{B*} \right)>\frac{1}{2K}\) for \({G}_{T}^{B*}\).

(iii) \(\Omega \left({G}_{T}^{C*}\right)>\frac{1}{2K}\) for \({G}_{T}^{C*}\).

These conditions might be simultaneously satisfied.

Appendix 2: Descriptive evidence and multivariate correlation analysis

Figure 3 presents education expenditure as a share of GDP in 2019 and its private and public funding composition for a sample of 43 high-middle income countries. It demonstrates the substantial variability in education expenditure and the significant differences in the source of funding among countries.Footnote 50 On average, the share of GDP devoted to education was about 5%, ranging from the lowest value in Romania (2.5%) up to the highest in Cyprus (6.9%). In terms of composition, on average 18% of education expenditure was from private funding, with the highest value in Peru (43%) and the lowest in Romania (0.1%).

Figure 4 presents the allocation of public expenditure on basic and tertiary education as shares of GDP. It shows a positive relationship between the two education tiers, but also a great variability: countries with the same share of public basic education might have very different expenditures on tertiary education.

Building on our theoretical results, we endeavour to analyse countries’ differences in education expenditures by relating these differences to the variations in income inequality and intergenerational persistence in education. To characterise these relationships, we perform multiple regression correlations. This analysis has only a descriptive purpose as the limited number of observations and endogeneity issues, due to reverse causality and omitted variables, pose major challenges for identifying causal effects. We have collected data on three education-spending variables (public basic, public tertiary and total private) and the proportion of public basic education expenditure on total public education expenditure (public basic/total public) for 43 high and middle income countries covering two time periods.Footnote 51 In the first period, expenditures are computed as averages over the years 2000 to 2009; in the second period, averages are computed over the years 2010 to 2019.Footnote 52 To mitigate the issue of a potential reverse causality link, whereby low public expenditure in education leads to more inequality and higher education persistence, we have considered the values of income inequality and intergenerational education persistence that precede the observed values of education expenditure.Footnote 53 Income inequality is measured by the variable GINI, which is the Gini index of disposable income for the years 2000 and 2010.Footnote 54 To assess intergenerational education persistence, we use the variable COR, which measures the correlation between the years spent on education by parent and child. We obtain data from the 2023 Global Database on Intergenerational Mobility from the World Bank (WB 2023) for the 1970s and 1980s cohort.Footnote 55 Moreover, as different standard of living may affect government spending on education, we include the real GDP per capita as a control variable.Footnote 56 Table 1 contains the descriptive statistics.

Table 2 presents the outcome of a pooled linear regression between the four education spending variables (public basic, public tertiary, total private and public basic/total public) and our two main variables of interest (COR and GINI). To control for time effects, we add a dummy that takes value 0 in the first period and value 1 in the second.

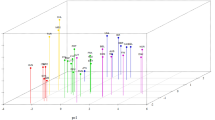

In line with the model, public expenditure on education (as percentage of GDP) is negatively correlated with COR and GINI.Footnote 57 COR is significant in the relationship with public basic education (Table 2, column 1), while GINI is relevant in the relationship with public tertiary education (Table 2, column 2). In column 3, we again consider public tertiary education and add an interaction term between COR and GINI. Consistent with the model’s results, the coefficients of COR and GINI are both significant and negative. The coefficient of the interaction term is positive and significant, implying that the negative relationship between intergenerational persistence in education and public tertiary spending declines as inequality increases. To clarify this relationship, we compute marginal effects (Fig. 5).

The sign of the marginal effect of COR on public tertiary spending is negative for low values of GINI and becomes positive for high values of income inequality. To explain why the negative correlation between COR and tertiary public expenditure becomes weaker as income inequality increases, note that private expenditures, which are mainly concentrated on tertiary education, are strongly and negatively correlated to GINI (see Table 2, column 4). Indeed, if providers of tertiary education are mainly private (e.g. in Anglo-Saxon countries), we observe a strong negative relationship between COR and tertiary education spending when considering private (tertiary) expenditure (see Table 2, column 4). As income inequality increases further, the marginal effect of COR on tertiary public education spending becomes positive. Indeed, at odds with our theoretical conjectures, in some countries where both income inequality and intergenerational persistence in education are remarkably high (e.g., Mexico, Turkey, Argentina and Chile), we observe that the allocation of public education expenditure is biased towards tertiary public education. This scenario might describe a situation where the private sector is not sufficiently developed and the political power is in the hands of well-educated minorities, who would benefit most from an increase in public tertiary education spending (see Su (2006)).Footnote 58 This circumstance is not captured by our model, whose assumptions about the political process are more apt to describe an environment where power is equally distributed.

In the last column of Table 2, we examine the share of public education spending devoted to basic education. We do not find any significant correlation between COR and the share of public basic education spending on total public expenditure. However, this share is significantly and positively correlated with GINI. This might be consistent with our model; as income inequality increases the weight of the middle class decreases and it is more likely the emergence of an equilibrium ends against the middle, as described by Epple and Romano (1996), where the interests of the well-educated elite who opts out of the public system—mainly at the tertiary level- become closer to the interests of poor, less educated agents who are not interested in tertiary public education. Finally, as expected, log real GDP per capita is positively and significantly correlated with public expenditure in both education tiers.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Gioacchino, D., Sabani, L. & Usai, S. Public Versus Private Investment in Education in a Two Tiers System: The Role of Income Inequality and Intergenerational Persistence in Education. Ital Econ J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00256-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-023-00256-0

Keywords

- Education funding

- Majority voting

- Income inequality

- Intergenerational persistence in education

- Tertiary education