Abstract

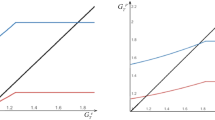

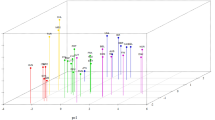

This paper proposes a theory to study the formulation of education policies and human capital accumulation. The government collects income taxes and allocates tax revenue to primary and higher education. The tax rate and the allocation rule are both endogenously determined through majority voting. The tax rate is kept at a low level, and public funding for higher education is not supported unless the majority of individuals have human capital above some threshold. Although public support for higher education promotes aggregate human capital accumulation, it may create long-run income inequality because the poor are excluded from higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Hidalgo-Hidalgo and Iturbe-Ormaetxe (2012) show that it is almost impossible to find a feasible policy reform that achieves a Pareto improvement. They develop a static model inhabited by individuals with heterogeneities in both innate ability and parental income, in which the government splits its resources between compulsory primary education and optional higher education. Hidalgo-Hidalgo and Iturbe-Ormaetxe (2012) introduce alternative measures of efficiency, and analyze the effects of policy reforms on the measures of efficiency and equity. As will be clarified soon, we consider the determination of an education policy through majority voting in a dynamic model.

Galor et al. (2009) present evidence that inequality in land, which is an early and primary form of wealth, has an adverse impact on education expenditure per child in the United States.

In our setup, the human capital of individuals is equal to their pre-tax income, and we assume that parents care about their children’s pre-tax income rather than their children’s disposable income. The children’s disposable income depends on the tax rate realized when the parents leave the economy and their children become adults. This assumption implies that parents do not derive utility from the state after their death. Parents can directly observe the human capital of their children, but they cannot observe the future tax rate and disposable income of their children.

Such a fixed cost is traditional in growth and development literature, at least since Galor and Zeira (1993).

The wage rate per unit of human capital may depend on the aggregate and average human capital. For example, if there is a positive externality in production, the wage rate should increase with aggregate and average human capital. In such cases, individuals would prefer a lower tax rate because a higher tax rate would decrease their consumption by more than it would in cases where there is no externality.

In the Hidalgo-Hidalgo and Iturbe-Ormaetxe (2012) model, the government provides subsidies that partially cover the private costs of higher education as well as improving the quality of primary and higher education.

Scholarships and other grants to households are 11.4 %.

Innate (preschool) human capital may be positively correlated with parental human capital because of parental care at the preschool age. Suppose, instead, that the innate human capital of individual i is given by \(\hat{h}_{it}=\delta h_{it}+\hat{h}\), where \(\delta >0\). Using this specification of innate ability would not alter our qualitative results.

We assume that human capital production exhibits the constant marginal product of parental human capital (see (4) and (5)). In the case where human capital production exhibits the decreasing marginal product of parental human capital, both primary and higher education have stronger redistributive effects from richer to poorer individuals. In such a case, the most preferred tax rates are represented as functions of individual human capital, and poorer individuals may have stronger incentives to raise the tax rate and obtain higher education. We question the redistributive effects of education, as described in Introduction, and our interest is the analysis within an environment in which the redistributive effects of education are sufficiently weak.

In some disciplines in which laboratory teaching in small classes is necessary, a congestion effect might emerge (e.g., in some engineering and medical classes). We abstract the congestion effect in such disaggregated disciplines, and assume that class size does not matter in considering aggregate human capital production. Although it is not necessary to consider congestion effects in primary education in our model, there is evidence that class size does not matter in primary education either. See Hoxby (2000) and Leuven et al. (2008).

In Glomm and Ravikumar (1992), Su (2004, (2006), and Naito (2012), inherited human capital is the only source of heterogeneity among individuals and has a positive effect on their educational outcome, as in our model specification. Blankenau (2005) and Blankenau et al. (2007b) also assume that parental human capital stock has a positive impact on the human capital acquisition of their children in school. On the empirical side, Hanushek (1986) points out that children of parents with higher human capital benefit more from school. Solon (1992), Zimmerman (1992), and Dearden et al. (1997) show empirically that the earnings of parents and their children are positively correlated, and that the degree of intergenerational mobility is limited.

Since \(H(x^{*},\tau ^{A})<\hat{H}\), \(\hat{H}<h^{P}\) implies \(H(x^{*},\tau ^{A})<h^{P}\).

The net income of lineage i with \(h_{i0}\ge H(x^{*},\tau ^{A})\) converges to \((1-\tau ^{A})h^{A}\), and the consumption level converges to \(c^{A}\equiv (1-\tau ^{A})h^{A}-1\). In contrast, the net income of lineage i with \(h_{i0}<H(x^{*},\tau ^{A})\) converges to \((1-\tau ^{A})h^{P}\), and the consumption level converges to \(c^{P}\equiv (1-\tau ^{A})h^{P}\). The pre-tax income inequality, \(h^{A}-h^{P}\), is reduced by taxation, and the inequality measured by consumption, \(c^{A}-c^{P}\), becomes even smaller because of the private cost of higher education. In particular, \(c^{A}\) can be smaller than \(c^{P}\) if \(\hat{h}\) is sufficiently small and/or \(\beta \) is sufficiently large. In this case, \(h^{A}-h^{P}\) is relatively small, and the taxation and private cost of higher education cause \(c^{P}>c^{A}\).

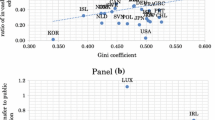

This theoretical consequence may fit the cases of countries such as Mexico and Peru. According to World Development Indicators, since 1994, the Gini coefficients of Mexico have been around 50, and those of Peru have ranged between 45 and 55. Possibly as a result of this high income inequality, there are many individuals who do not receive higher education: the gross enrolment ratios in tertiary education in Mexico and Peru are about 30 and 40 %, respectively. This may be the cause of persistent income inequality in these two countries.

References

Abington C, Blankenau W (2013) Government education expenditures in early and late childhood. J Econ Dyn Control 37:854–874

Arcalean C, Schiopu I (2010) Public versus private investment and growth in a hierarchical education system. J Econ Dyn Control 34:604–622

Blankenau W (2005) Public schooling, college subsidies and growth. J Econ Dyn Control 29:487–507

Blankenau W, Cassou SP, Ingram B (2007a) Allocating government education expenditures across K-12 and college education. Econ Theory 31:85–112

Blankenau W, Simpson NB, Tomljanovich M (2007b) Public education expenditures, taxation, and growth: linking data to theory. Am Econ Rev 97:393–397

Dearden L, Machin S, Reed H (1997) Intergenerational mobility in Britain. Econ J 107:47–66

Easterly W (2001) The middle class consensus and economic development. J Econ Growth 6:317–335

Easterly W (2007) Inequality does cause underdevelopment: insights from a new instrument. J Dev Econ 84:755–776

Fernandez R, Rogerson R (1995) On the political economy of education subsidies. Rev Econ Stud 62:249–262

Galor O, Moav O, Vollrath D (2009) Inequality in landownership, the emergence of human-capital promoting institutions, and the great divergence. Rev Econ Stud 76:143–179

Galor O, Zeira J (1993) Income distribution and macroeconomics. Rev Econ Stud 60:35–52

Glomm G, Ravikumar B (1992) public versus private investment in human capital: endogenous growth and income inequality. J Political Econ 100:818–834

Hanushek EA (1986) The economics of schooling: production and efficiency in public schools. J Econ Lit 24:1141–1177

Hidalgo-Hidalgo M, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I (2012) Should we transfer resources from college to basic education? J Econ 105:1–27

Hill MC (1998) Class size and student performance in introductory accounting courses: further evidence. Issues Account Educ 13:47–64

Hoxby C (2000) The effects of class size on student achievement: new evidence from population variation. Q J Econ 115:1239–1285

Kennedy PE, Siegfried JJ (1997) Class size and achievement in introductory economics: evidence from TUCE III data. Econ Educ Rev 16:385–394

Leuven E, Oosterbeek H, Rønning M (2008) Quasi-experimental estimates of the effect of class size on achievement in Norway. Scand J Econ 110:663–693

Machado MP, Vera-Hernandez M (2008) Does class-size affect the academic performance of first year college students? University College London, Mimeo, New York

Naito K (2012) Two-sided intergenerational transfer policy and economic development: a politico-economic approach. J Econ Dyn Control 36:1340–1348

Naito K, Nishida K (2012) The effects of income inequality on education policy and economic growth. Theoret Econ Lett 2:109–113

OECD (2013) Education at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris

Persson T, Tabellini G (2000) Political economics: explaining economic policy. MIT Press, Cambridge

Restuccia D, Urrutia C (2004) Intergenerational persistence of earnings: the role of early and college education. Am Econ Rev 94:1354–1378

Saint-Paul G, Verdier T (1993) Education, democracy and growth. J Dev Econ 42:399–407

Siegfried JJ, Kennedy PE (1995) Does pedagogy vary with class size in introductory economics? Am Econ Rev 85:347–351

Solon G (1992) Intergenerational income mobility in the United States. Am Econ Rev 82:393–408

Su X (2004) The allocation of public funds in a hierarchical education system. J Econ Dyn Control 28:2485–2510

Su X (2006) Endogenous determination of public budget allocation across education stages. J Dev Econ 81:438–456

Zimmerman DJ (1992) Regression toward mediocrity in economic stature. Am Econ Rev 82:409–429

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editor, Giacomo Corneo, and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank Akihisa Shibata, Shiro Kuwahara, Carlos Bethencourt, and conference participants of PET 12. Any remaining errors are ours. This research is financially supported by the Global COE program of Osaka University, the Central Research Institute of Fukuoka University (No. 144002), and the Joint Research Program of KIER.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Naito, K., Nishida, K. Multistage public education, voting, and income distribution. J Econ 120, 65–78 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-016-0513-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-016-0513-5