Abstract

Background

It is unclear whether highly fragmented ambulatory care (i.e., care spread across multiple providers without a dominant provider) increases the risk of an emergency department (ED) visit. Whether any such association varies with race is unknown.

Objective

We sought to determine whether highly fragmented ambulatory care increases the risk of an ED visit, overall and by race.

Design and Participants

We analyzed data for 14,361 participants ≥ 65 years old from the nationwide prospective REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort study, linked to Medicare claims (2003–2016).

Main Measures

We defined high fragmentation as a reversed Bice-Boxerman Index ≥ 0.85 (≥ 75th percentile). We used Poisson models to determine the association between fragmentation (as a time-varying exposure) and ED visits, overall and stratified by race, adjusting for demographics, medical conditions, medications, health behaviors, psychosocial variables, and physiologic variables.

Key Results

The average participant was 70.5 years old; 53% were female, and 33% were Black individuals. Participants with high fragmentation had a median of 9 visits to 6 providers, with 29% of visits by the most frequently seen provider; participants with low fragmentation had a median of 7 visits to 3 providers, with 50% of visits by the most frequently seen provider. Overall, high fragmentation was associated with more ED visits than low fragmentation (adjusted risk ratio [aRR] 1.31, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29, 1.34). The magnitude of this association was larger among Black (aRR 1.48, 95% CI 1.44, 1.53) than White participants (aRR 1.23, 95% CI 1.20, 1.25).

Conclusions

Highly fragmented ambulatory care was an independent predictor of ED visits, especially among Black individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Older adults in the U.S. routinely see multiple ambulatory providers, which may be clinically appropriate.1,2 However, providers caring for the same patient do not consistently share clinical information with each other.3 As a result, highly fragmented ambulatory care (i.e., care spread across many providers without a dominant provider) increases the likelihood of gaps in communication of clinical information.4 These gaps can then lead to undesirable events, such as drug-drug interactions,5 repeat tests,6 and unnecessary procedures.7

Previous studies suggest that highly fragmented ambulatory care is also associated with subsequent emergency department (ED) visits.8,9,10,11,12 However, those studies have limitations. Some studies were based entirely on claims data, which lack clinical detail, and thus may be more subject to unmeasured confounding.8,10,12 Other studies were conducted in the Veterans Health Administration, which may not be generalizable to other settings.9 Still others were conducted in a single state10,11 or were restricted to those with specific diseases, such as diabetes.8,11

Black adults are less likely to have highly fragmented ambulatory care13 but substantially more likely to have ED visits than White adults.14 We previously found that race can modify the relationship between fragmentation and health outcomes (e.g., stroke).15 Thus, there is a need to determine whether the relationship between fragmentation and ED visits varies with race. If the association between fragmentation and ED visits is stronger among Black vs. White adults, this may illuminate a novel opportunity to address racial disparities.16

We sought to determine the association between highly fragmented ambulatory care and ED visits, overall and by race, while using both clinical data and claims from a nationwide sample.

METHODS

Overview

We analyzed data from the prospective REGARDS cohort study (2003–2016). Institutional review boards of the participating institutions approved the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study Population

Between 2003 and 2007, the REGARDS study enrolled 30,239 community-dwelling, English-speaking adults in the U.S. who were ≥ 45 years old.17 The study design involved oversampling of adults in the Southeastern U.S., balanced sampling of White and Black individuals, and balanced sampling of men and women.17 Participants were not selected on the basis of stroke risk (other than the risk conferred by geography, race, and sex).

Data Sources

REGARDS collected data at baseline with a computer-assisted telephone interview and an in-home study visit, including a physical examination, blood and urine tests, an electrocardiogram, and a medication inventory.17 REGARDS data are also linked to Medicare fee-for-service claims (Beneficiary, Carrier, Outpatient, and Inpatient files). REGARDS participants with linked Medicare fee-for-service claims have been shown to be representative of the national population of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries.18

Defining the Study Sample

We included REGARDS participants ≥ 65 years old whose cohort data were linked to Medicare fee-for-service claims at any time during the study period; that is, we included those who were ≥ 65 years old at the REGARDS baseline, and we also allowed participants to age into Medicare and enter this ancillary study during the REGARDS follow-up. We excluded those who (1) qualified for Medicare on the basis of having end-stage renal disease, as ambulatory care utilization for these beneficiaries is distinct;19 (2) had < 13 months of continuous Medicare fee-for-service coverage, because 13 months is needed to measure a 12-month exposure period plus a 1-month outcome period, as described below; (3) had missing provider information for all providers seen; (4) had an event in every 12-month exposure period (ED visit, hospitalization, or death); or (5) had < 4 ambulatory visits in every 12-month exposure period, because measuring fragmentation with < 4 visits can lead to unreliable statistical estimates.20

Variables

Healthcare Fragmentation. To measure ambulatory care fragmentation, we first identified ambulatory visits in Medicare claims, using a modified version of the definition by the National Commission for Quality Assurance (NQCA), which we have used previously.6,21 This modified definition restricts ambulatory visits to in-person, evaluation-and-management visits or wellness visits for adults in an office or clinic setting.6,21 The NCQA definition does not include ED visits.

We calculated ambulatory care fragmentation using the Bice-Boxerman Index (BBI).22 Using 12 months of data at a time, this index incorporates the total number of visits with non-missing provider information, the total number of providers, and the distribution of visits across those providers to yield a single score, ranging from 0 (each visit with a different provider) to 1 (all visits with the same provider). We reversed the index, calculating 1 minus BBI, so that higher scores reflect more fragmentation.11

ED Visits. We identified ED visits in Medicare claims and included only ED visits that resulted in discharge (to home or elsewhere). An ED visit that resulted in a hospital admission was considered part of an admission and not counted as an ED visit.23

Potential Confounders. We used the Aday-Anderson framework for access to medical care to guide our selection of potential confounders.24,25 We choose this framework because it explicitly articulates fragmented care as a type of healthcare utilization. The Aday-Anderson framework posits that healthcare utilization is informed by individual predisposing characteristics, enabling resources, and medical need. We selected the following REGARDS baseline variables as potential confounders (and show in Supplemental Figure 1 how they map onto the Aday-Anderson framework): demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, marital status, education, annual household income, geographic region, and residence in an urban area); medical conditions (hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and stroke); medications (number of medications, anti-hypertensive medication, insulin use, and statin use); health behaviors (smoking, alcohol use, exercise); psychosocial variables (being a family caregiver, social support, depressive symptoms, self-rated general health, self-rated physical health, and self-rated mental health); and physiologic variables (body mass index, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, and c-reactive protein). Definitions of these variables are shown in Supplemental Table 1.26,27,28,29,30,31

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive Statistics. We used descriptive statistics to characterize ambulatory care utilization in the first year of observation: the number of visits, the number of providers, the proportion of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and the fragmentation score. We then dichotomized fragmentation scores into high (≥ 0.85) and low (< 0.85). This cut-point corresponded to the 75th percentile; values at or above this cut-point have previously been associated with an increased hazard of hospitalization.23 We used descriptive statistics to characterize our sample, overall and stratified by fragmentation score in the first year of observation, using Wilcoxon rank sum tests, t tests, and chi-squared tests. We also generated descriptive statistics stratified by race.

Analytic Design. In our analysis, we treated fragmentation as a time-varying exposure. The rationale for this was that the mechanism through which fragmentation may lead to an ED visit may unfold relatively quickly (i.e., on the order of days or weeks); for example, a drug-drug interaction in the context of multiple prescribers who are unaware of each other’s prescribing may cause an adverse drug event relatively quickly, which may require emergency medical attention.4 Observation for each participant started after the baseline REGARDS in-home visit with the first 12-month period for which there was continuous Medicare coverage, beginning with calendar year 2004. For each participant, we calculated a fragmentation score for the first 12 months of his or her observation period. We then determined if at least one ED visit occurred in the following month (e.g., month 13). If not, we moved the window of observation forward by 1 month (e.g., recalculating fragmentation for months 2–13 and assessing the occurrence of an ED visit in month 14). If at least one ED visit occurred, we counted that as an outcome; we counted only one ED visit per month.

Because we had 13 years of follow-up data and because ED visits were common, using only the first ED visit would cause us to lose a substantial portion of our data. Thus, in our primary analysis, we allowed participants to re-enter the cohort after a first ED visit (“multiple-event sample”). That is, after the first ED visit, we re-started observation with the next 12-month exposure period (not including the month with the index ED visit) that did not have a hospitalization (since hospitalized participants are not at risk for an ED visit). If a participant had a hospitalization during a qualifying outcome period, the participant was censored for that outcome period but was allowed to return to the cohort with the next 12-month period without a hospitalization. Observation continued until the participant was permanently censored (due to death, drop** out of the REGARDS study, or no longer having Medicare fee-for-service coverage) or reached the end of follow-up (December 31, 2016). We show a schematic depicting this analytic approach in Supplemental Figure 2. We conducted a sensitivity analysis counting only the first ED visit per participant (“incident-event sample”), with the schematic for that approach shown in Supplemental Figure 3.

Association Between Fragmentation and ED Visits. We tallied the number of ED visits and person-years of observation, stratified by high vs. low fragmentation and race. We used Poisson models to estimate unadjusted and adjusted absolute rates of ED visits per 1000 person-years with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used the same Poisson models to estimate unadjusted and adjusted risk ratios with 95% CIs. We calculated a formal interaction term for fragmentation*race, which we considered significant at p < 0.10. We adjusted for all potential confounders that were associated with fragmentation in bivariate models (p < 0.10). Highly skewed potential confounders were log-transformed. Robust standard errors accounted for multiple observations per participant.

We also estimated each fully adjusted Poisson model using stochastic imputation, a single imputation technique that adds a residual error term to each imputed predicted value, thereby preserving uncertainty while reducing bias.32 We chose this approach instead of multiple imputation due to the complexity of modeling a time-varying exposure. The most frequently missing covariate was c-reactive protein (missing for 6%).

We conducted stepwise model building as a sensitivity analysis, adding one group of potential confounders at a time, to assess the extent to which any given group of variables influenced the effect size and statistical significance. Additional sensitivity analyses varied how fragmentation scores were categorized; we tried alternate dichotomous cut points (≥ 0.75, and separately ≥ 0.90), as well as a 3-category version (0.00–0.50 low, 0.51–0.75 moderate, and 0.76–1.00 high fragmentation).

The Poisson models had no evidence of overdispersion.

Analyses were conducted with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata (version 14; StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study Sample

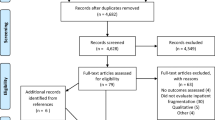

The multiple-event sample consisted of 14,361 participants and served as our primary sample (Supplemental Figure 4). The incident-event sample consisted of 9809 participants and was used for sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Figure 5).

Participant Characteristics

The average age of participants in the multiple-event sample was 70.5 years (SD 6.0). Approximately half the participants (53%) were female, and one-third (33%) were Black individuals. Of the total, 63% had hypertension, 63% had dyslipidemia, and 23% had diabetes. Participants with high fragmentation were younger, more likely to be White, and less likely to have hypertension or diabetes than participants with low fragmentation. Additional participant characteristics by fragmentation score are shown in Table 1. Characteristics of the multiple-event sample stratified by race are shown in Supplemental Table 2. Characteristics of the incident-event sample, overall and by race, are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

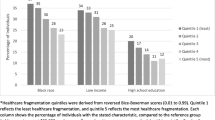

Ambulatory Care Utilization

In the multiple-event sample, participants with high fragmentation in the first year of observation had a median of 9 visits to 6 providers, 29% of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and a fragmentation score of 0.90 (Table 2). By contrast, participants with low fragmentation in the first year of observation had a median of 7 visits to 3 providers, 50% of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and a fragmentation score of 0.70. More than one-fourth of White participants (27%) had high fragmentation, whereas one-fifth (20%) of Black participants had high fragmentation. These patterns were similar in the incident-event sample (Supplemental Table 4).

ED Visits

Overall, 26% of participants never experienced an ED visit, 18% experienced only 1 ED visit, and 56% experienced ≥ 2 ED visits during follow-up (Supplemental Table 5). Participants in the multiple-event sample experienced a total of 51,627 ED visits over 64,055 person-years, with a median observation time of 3.9 years (range 2 days to 12.2 years) (Table 3). By contrast, participants in the incident-event sample experienced a total of 3678 ED visits over 28,741 person-years, with a median observation time of 2.0 years (range 2 days to 12.2 years) (Supplemental Table 6).

Association Between Ambulatory Care Fragmentation and ED Visits

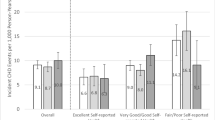

Overall, the adjusted rate of ED visits was 945 (95% CI 929, 961) per 1000 person-years in the high fragmentation group, compared to 721 (95% CI 712, 729) per 1000 person-years in the low fragmentation group (p < 0.0001, Table 3). The interaction term for fragmentation*race was significant (p < 0.0001). The association between fragmentation and ED visits was significant among White and Black participants, but the magnitude was greater among Black participants (Fig. 1).

Adjusted rates of emergency department visits with 95% confidence intervals, over the duration of the 12-year follow-up period, by race and by ambulatory care fragmentation. Fragmentation score was calculated with the reversed Bice-Boxerman Index, using 12 months of data at a time. High fragmentation was defined as a score ≥ 0.85, which was equivalent to the 75th percentile for the total sample. Low fragmentation was defined as a score < 0.85. Fragmentation was modeled as a time-varying exposure. Adjusted rates are based on Poisson models that account for age, sex, marital status, education, income, geographic region, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, medication count, smoking status, alcohol use, self-rated general health, physical component summary score, body mass index, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (log-transformed), and c-reactive protein (log-transformed). The pairwise differences in the adjusted rates of ED visits for high vs. low fragmentation are statistically significant for both White participants (p < 0.001) and Black participants (p < 0.001). The pairwise differences in the adjusted rates of ED visits for White participants vs. Black participants were significant among those with low fragmentation (p < 0.001) and among those with high fragmentation (p < 0.001).

Overall, in the fully adjusted model with imputation, participants with high fragmentation in any 12-month period had a 31% (95% CI 29%, 34%) higher adjusted risk of an ED visit in the following month compared to participants with low fragmentation (Table 4). Among White participants, those with high fragmentation had a 23% (95% CI 20%, 25%) higher adjusted risk of an ED visit compared to low fragmentation. Among Black participants, those with high fragmentation had a 48% (95% CI 44%, 53%) higher adjusted risk of an ED visit compared to those with low fragmentation. Models built stepwise showed that these results were robust and not substantially influenced by any particular group of potential confounders (Supplemental Table 7). These results were also robust to alternate cut points for defining high fragmentation (Supplemental Table 8).

When we repeated this analysis using the incident-event sample, the risk ratios were in the same direction as in the analysis using the multiple-event sample, but the magnitudes were smaller and did not reach statistical significance (Supplemental Table 9).

DISCUSSION

In this nationwide study of 14,361 Medicare beneficiaries ≥ 65 years old, highly fragmented ambulatory care over any 12-month period was associated with a 31% higher risk of an ED visit in the following 1-month period than less fragmented care, even after adjusting for demographic characteristics, medical conditions, medications, health behaviors, psychosocial variables, and physiologic variables. While highly fragmented care was associated with subsequent ED visits for both White and Black participants, the magnitude of the association was larger for Black participants.

Our finding of an overall increased risk of 31% for high vs. low fragmentation is larger than effect sizes observed in previous studies, although these comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the underlying study populations, settings, and methods vary. Previous studies found that high fragmentation was associated with a 1% to 15% increased risk of an ED visit.8,9,10,11,12 Previous studies have not published rates of ED visits per 1000 person-years, nor have they explored interactions by race.

There are at least two possible interpretations of our findings. First, it is possible that highly fragmented care leads to poor quality care (e.g., prescription of medications that interact with each other, unnecessary procedures with adverse effects, suboptimal control of chronic medical conditions, or misdiagnosis due to a failure to detect clinical patterns)4,5,7,33,34 and then that poor quality care leads to the need for an ED visit. Alternatively, it is possible that Medicare beneficiaries seek more care from more providers as they get more acutely ill. In this scenario, worsening physiology leads to more fragmentation of care just prior to an ED visit. If this is the case, then fragmentation of care would portend an ED visit. More research is needed to determine which interpretation is correct.

There are several possible theories for why the relationship between fragmentation and ED visits was stronger for Black participants than White participants. We previously found that even when Black and White Medicare beneficiaries have similar total ambulatory visit counts, Black participants have fewer visits with specialists,13 which could be a factor if specialists could help avert an ED visit. Other theories are that the quality of the providers for Black participants was worse than the quality of providers for White participants,35 or that the quality of communication among providers for Black participants was worse than that for White participants.36 Structural racism (that is, racism that goes beyond individual prejudice and is embedded in institutional practices) could contribute to this disparity,37 although our data do not allow us to test that theory directly.38,39 More research is needed to understand this disparity.

Our study has several strengths, including the national scale, large sample size, clinically detailed covariates, sufficiently powered subgroup analyses by race, comprehensive Medicare claims, a previously validated measure of fragmentation, and more than 12 years of data.

Several limitations merit discussion. First, this study is observational; we cannot infer causation, determine the directionality of any relationship, or rule out unmeasured confounding. Second, results cannot be generalized to Medicare beneficiaries with fewer than 4 visits, who were excluded from this analysis and who are generally healthier than the beneficiaries we included.10 Third, we cannot determine the clinical appropriateness of the ambulatory visits or ED visits. Fourth, REGARDS measured covariates at baseline, and it is possible that those covariates changed over time; however, other studies have found that REGARDS covariates at baseline are highly predictive of long-term outcomes.40 Fifth, our sensitivity analysis with incident events had only 7% of the events in our multiple-event analysis (3678 vs. 51,627 ED visits) and may have been underpowered.

In terms of implications, payers, including Medicare, have access to ambulatory utilization in real time or near real time and could potentially detect patterns of fragmented care as they unfold. Many accountable care organizations (ACOs) have access to Medicare claims with a fairly short lag time,41 which could allow ACOs to identify beneficiaries with fragmented care, deploy care coordinators they already employ42 to assess the risk for ED visits, and have those care coordinators intervene to address any problems they detect.

In conclusion, highly fragmented ambulatory care was independently associated with subsequent ED visits, particularly among Black individuals. Identifying fragmented care as it occurs could create opportunities for intervention, potentially averting subsequent ED visits and reducing racial disparities.

References

Barnett ML, Bitton A, Souza J, Landon BE. Trends in outpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries and implications for primary care, 2000 to 2019. Ann Intern Med 2021;174(12):1658-1665.

Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1130-9.

O'Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:56-65.

Kern LM, Safford MM, Slavin MJ, et al. Patients' and providers' views on the causes and consequences of healthcare fragmentation. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:899-907.

Guo JY, Chou YJ, Pu C. Effect of continuity of care on drug-drug interactions. Med Care 2017;55:744-51.

Kern LM, Seirup JK, Casalino LP, Safford MM. Healthcare fragmentation and the frequency of radiology and other diagnostic tests: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:175-81.

Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The association between continuity of care and the overuse of medical procedures. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1148-54.

Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Pollack CE. Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:742-8.

Katz DA, McCoy KD, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS. Does greater continuity of Veterans Administration primary care reduce emergency department visits and hospitalization in older Veterans? J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(12):2510-2518.

Kern LM, Seirup J, Rajan M, Jawahar R, Stuard SS. Fragmented ambulatory care and subsequent healthcare utilization among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care 2018;24:e278-e84.

Liu CW, Einstadter D, Cebul RD. Care fragmentation and emergency department use among complex patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:413-20.

Nyweide DJ, Bynum JPW. Relationship between continuity of ambulatory care and risk of emergency department episodes among older adults. Ann Emerg Med 2017;69:407-15 e3.

Kern LM, Rajan M, Colantonio LD, et al. Differences in ambulatory care fragmentation by race. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:154.

Hanchate AD, Dyer KS, Paasche-Orlow MK, et al. Disparities in emergency department visits among collocated racial/ethnic Medicare enrollees. Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:225-35.

Kern LM, Ringel J, Rajan M, et al. Ambulatory care fragmentation and incident stroke. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10(9):e019036.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005;25:135-43.

**e F, Colantonio LD, Curtis JR, et al. Linkage of a populaton-based cohort with primary data collection to Medicare claims: The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Epidemiol 2016;184:532-44.

U.S. Renal Data System. Chapter 9: Healthcare expenditures for persons with ESRD. 2017. (Accessed October 7, 2022, at https://www.usrds.org/media/1734/v2_c09_esrd_costs_18_usrds.pdf.)

Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1879-85.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS Volume 2: Technical Specifications. 2015. (Accessed October 7, 2022, at http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISMeasures/HEDIS2015.aspx.)

Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care 1977;15:347-9.

Kern LM, Ringel JB, Rajan M, et al. Ambulatory care fragmentation and subsequent hospitalization: evidence from the REGARDS study. Med Care 2021 Apr 1;59(4):334-340.

Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9:208-20.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1-10.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes, 2020. (Accessed October 7, 2022, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx.)

National Kidney Foundation. Albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR), 2022. (Accessed October 7, 2022, at https://www.kidney.org/kidneydisease/siemens_hcp_acr.)

Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S, Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28:829-47.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604-12.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. App Psycholog Measure 1977;1:385-401.

Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220-33.

Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley; 2002.

Ganguli I, Simpkin AL, Lupo C, et al. Cascades of care after incidental findings in a US national survey of physicians. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1913325.

Maciejewski ML, Hammill BG, Bayliss EA, et al. Prescriber continuity and disease control of older adults. Med Care 2017;55:405-10.

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med 2004;351:575-84.

Martino SC, Elliott MN, Hambarsoomian K, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in Medicare beneficiaries' care coordination experiences. Med Care 2016;54:765-71.

Bailey ZD, Feldman JM, Bassett MT. How structural racism works - racist policies as a root cause of U.S. racial health inequities. N Engl J Med 2021;384:768-73.

Adkins-Jackson PB, Chantarat T, Bailey ZD, Ponce NA. Measuring structural racism: a guide for epidemiologists and other health researchers. Am J Epidemiol 2022;191:539-47.

Hardeman RR, Homan PA, Chantarat T, Davis BA, Brown TH. Improving the measurement of structural racism to achieve antiracist health policy. Health Aff (Millwood) 2022;41:179-86.

Kern LM, Rajan M, Ringel JB, et al. Healthcare fragmentation and incident acute coronary heart disease events: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2021;36:422-9.

Berwick DM. Making good on ACOs' promise--the final rule for the Medicare shared savings program. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1753-6.

Evans M Demand grows for care coordinators. Modern Healthcare, March 28, 2015. (Accessed October 7, 2022, at https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150328/MAGAZINE/303289980/demand-grows-for-care-coordinators).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Role of the Funding Agencies

The funding agencies played no role in the design or conduct of the study, and no role in data management, data analysis, interpretation of data, or preparation of the manuscript. The REGARDS Executive Committee reviewed and approved this manuscript prior to submission, ensuring adherence to standards for describing the REGARDS study.

Funding

The REGARDS study is co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute on Aging, of the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (U01 NS041588). The ancillary study on healthcare fragmentation and cardiovascular outcomes was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL135199).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

LMK is a consultant to Mathematica, Inc.

MR receives fees from the Veterans Biomedical Research Institute.

LDC and MMS receive funds from Amgen, Inc.

The other authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(PDF 168 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kern, L.M., Ringel, J.B., Rajan, M. et al. Ambulatory Care Fragmentation, Emergency Department Visits, and Race: a Nationwide Cohort Study in the U.S.. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 873–880 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07888-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07888-5