Abstract

Background

Highly fragmented ambulatory care (i.e., care spread across many providers without a dominant provider) has been associated with excess tests, procedures, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations. Whether fragmented care is associated with worse health outcomes, or whether any association varies with health status, is unclear.

Objective

To determine whether fragmented care is associated with the risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, overall and stratified by self-rated general health.

Design and Participants

We conducted a secondary analysis of the nationwide prospective Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort study (2003–2016). We included participants who were ≥ 65 years old, had linked Medicare fee-for-service claims, and had no history of CHD (N = 10,556).

Main Measures

We measured fragmentation with the reversed Bice-Boxerman Index. We used Cox proportional hazards models to determine the association between fragmentation as a time-varying exposure and adjudicated incident CHD events in the 3 months following each exposure period.

Key Results

The mean age was 70 years; 57% were women, and 34% were African-American. Over 11.8 years of follow-up, 569 participants had CHD events. Overall, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the association between high fragmentation and incident CHD events was 1.14 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92, 1.39). Among those with very good or good self-rated health, high fragmentation was associated with an increased hazard of CHD events (adjusted HR 1.35; 95% CI 1.06, 1.73; p = 0.01). Among those with fair or poor self-rated health, high fragmentation was associated with a trend toward a decreased hazard of CHD events (adjusted HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.29, 1.01; p = 0.052). There was no association among those with excellent self-rated health.

Conclusion

High fragmentation was associated with an increased independent risk of incident CHD events among those with very good or good self-rated health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Receiving ambulatory care from multiple providers is common.1 For example, 50% of Medicare beneficiaries nationally see 7 or more different physicians each year.1 This may be clinically appropriate, but it creates challenges, as providers often do not communicate with each other regarding their common patients.2,3 As a result, clinically relevant information, such as the results of tests ordered by another physician, is missing in 1 out of every 7 visits.4 More fragmented ambulatory care (that is, care spread across many providers without a dominant provider) has been associated with more testing,5 more procedures,6 more emergency department visits,7,8,9 and more hospitalizations,7,10 compared to less fragmented care. However, the relationship between fragmented ambulatory care and health outcomes is unclear.11

We previously found that the association between fragmented ambulatory care and subsequent healthcare utilization varies with patients’ health status.5,12 We hypothesize that the association between fragmented ambulatory care and health outcomes might also vary with health status. Healthy people might be able to see multiple providers without experiencing harm from gaps in communication, whereas sicker individuals might be more vulnerable to harm.

Prior to a myocardial infarction (MI), many patients have cardiovascular risk factors,13 such as hypertension and diabetes, which are often managed by multiple ambulatory providers (primary care physicians, cardiologists, endocrinologists, and others).14 We sought to determine whether more fragmented ambulatory care is associated with an increased risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, overall and by health status.

METHODS

Study Design, Population, and Data Sources

We conducted an ancillary study to the nationwide, prospective Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) cohort study, using data from 2003 to 2016.15 Institutional review boards of the participating institutions approved the protocol. All participants provided written informed consent.

Between 2003 and 2007, 30,239 community-dwelling African-American and white adults ≥ 45 years old were enrolled in the REGARDS study, with oversampling of African-American adults and individuals living in the Southeastern U.S.15 Baseline data collection involved computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) and in-home visits with a physical examination, blood test, urine test, electrocardiogram (ECG), and medication inventory. Participants or their proxies are contacted by telephone every 6 months to detect study endpoints. The report of a potential event triggers adjudication, which involves an expert review of medical records, death certificates, proxy interviews, autopsy reports, the Social Security Death Index, and the National Death Index (NDI).16

For this study, we used REGARDS study baseline data, REGARDS-adjudicated events, and REGARDS-linked Medicare claims data.37 The most frequently missing variable was C-reactive protein (missing for 6%); 85% of the sample was included in the complete case analysis. Second, we restricted the analysis to those ≥ 65 years old at baseline, excluding those who aged into Medicare over the study period. Third, we changed the time period for outcomes from 3 to 6 months immediately following each exposure period. Fourth, we used all unique covariates (not including variables embedded in the definitions of other variables), instead of selecting covariates based on bivariate p values, with a complete case approach. Fifth, we used all unique covariates, with multiple imputation to handle missing covariate values. Sixth, we stratified the sample into 5 self-rated health groups instead of 3.

Analyses were conducted with SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC) and Stata (version 14, StataCorp, College Station, TX). Multivariate p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Of the REGARDS study participants, 10,566 met the inclusion criteria (Appendix 3). The mean age of participants was 70 years (Table 1, Appendix 4). More than half of participants (57%) were women, and 34% were African-American. Two-thirds (66%) had very good or good self-rated health. By design, one-fourth (25%) had high fragmentation. Differences in participant characteristics between those with high vs. low fragmentation in the first year of observation are shown in Table 1. Participant characteristics stratified by self-rated health are shown in Appendix 5.

Ambulatory Utilization

Those with high fragmentation had an average of 10.7 visits across 6.3 providers, an average of 29% of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and an average fragmentation score of 0.91; by contrast, those with low fragmentation had an average of 8.8 visits across 3.5 providers, an average of 58% of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and an average fragmentation score of 0.63 (Table 2, p < 0.001 for each comparison).

Within each self-rated health group, those with high fragmentation had more visits, more providers, a lower proportion of visits with the most frequently seen provider, and higher fragmentation scores than those with low fragmentation (p < 0.001 for each comparison).

CHD Events

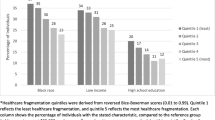

Participants were followed up for up to 11.8 years (median 5.5 years) (Table 3). Overall, 569 participants (5.4%) experienced an acute incident CHD event, equivalent to an unadjusted rate of 8.8 events per 1000 person-years. Those with worse self-rated health at baseline had more CHD events: 4.0% of those with excellent self-rated health, 5.4% of those with very good/good self-rated health, and 6.9% of those with fair/poor self-rated health had a CHD event (p = 0.001). Adjusted incidence rates are shown in Figure 1.

Absolute adjusted rates of incident coronary heart disease (CHD) events, stratified by healthcare fragmentation status and self-rated general health. Adjusted rates were derived from Poisson models that adjusted for age, gender, race, marital status, educational attainment, income, region, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, body mass index, albumin-to-creatinine ratio, C-reactive protein, number of medications, smoking, alcohol use, and lack of social support. Fragmentation status is a time-varying exposure based on the reversed Bice-Boxerman Index (low < 0.85, high ≥ 0.85). See “METHODS” for more details.

Overall, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the association between fragmentation and CHD events was 1.14 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92, 1.39) (Table 4, Appendix 6). However, there was an interaction between fragmentation and self-rated health (Wald test: p < 0.01). Among those with excellent self-rated health, there was no association between fragmentation and CHD events (adjusted HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.53, 1.57; p = 0.74). Among those with very good or good self-rated health, high fragmentation was associated with an increased hazard of CHD events (adjusted HR 1.35; 95% CI 1.06, 1.73; p = 0.01), compared to low fragmentation. Among those with fair or poor self-rated health, high fragmentation was associated with a trend toward a decreased hazard of CHD events (adjusted HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.29, 1.01; p = 0.052).

Results persisted in the sensitivity analyses that used the base case set of covariates with multiple imputation, the 6-month outcome period, all covariates with a complete case approach, and all covariates with a multiple imputation approach (Appendix 7). In the sensitivity analysis that excluded participants < 65 years old at baseline, the results for excellent and very good/good self-rated health persisted, and the results for fair/poor self-rated health reached statistical significance (adjusted HR 0.42; 95% CI 0.20, 0.91). In the sensitivity analysis stratifying self-rated health into 5 groups, confidence intervals were wider and high fragmentation was associated with a decreased hazard of CHD events in the fair self-rated health group (adjusted HR 0.43; 95% CI 0.20, 0.92, Appendix 8).

DISCUSSION

In this 12-year study of 10,556 Medicare beneficiaries from the REGARDS cohort, the association between fragmented ambulatory care and incident CHD events varied with health status. Among those with very good or good self-rated health, having highly fragmented care was associated with an increased adjusted hazard of a CHD event in the 3 months following the exposure. Among those with fair or poor self-rated health, having highly fragmented care was associated with a decreased adjusted hazard a CHD event over the same time period. Among those with excellent self-rated health, there was no association between fragmentation and CHD events. The ambulatory care patterns underlying high vs. low fragmentation were clinically and statistically different from each other: those with high fragmentation had an average of 11 visits to 6 providers per year, with the most frequently seen provider accounting for 29% of the visits, whereas those with low fragmentation had an average of 9 visits to 4 providers per year, with the most frequently seen provider accounting for 58% of visits.

These results are concordant with our previous study of Medicare beneficiaries in New York State, which found that healthcare fragmentation was not associated with hospitalizations among those with 0 chronic conditions, was associated with an increased hazard of hospitalization among those with 1–4 chronic conditions, and was associated with a decreased hazard of hospitalization among those with ≥ 5 chronic conditions.12 Other studies of fragmentation have adjusted for burden of illness (rather than stratify), precluding additional comparisons.6,7,10

The exact mechanisms by which fragmentation could increase or decrease cardiac risk, depending on health status, are not clear. On the one hand, sicker patients may require more providers,1 and providers may make more of an effort to coordinate care for sick patients,39 thereby ameliorating the risk of gaps in communication. Sicker patients may also have access to more ancillary providers like care managers, who may facilitate care coordination.40 On the other hand, for patients with a moderate burden of illness, more fragmented care may lead to worse control of cardiac risk factors, through less aggressive management of those risk factors or discontinuation of beneficial medications.41,42,43,44 Multiple providers may also unknowingly prescribe drugs that interact, exacerbating cardiac risk factors.45,46,47 More work is needed to distinguish between beneficial and deleterious care fragmentation.

Strengths of this study include the national sampling frame, large sample size, long time horizon, homogeneity of insurance benefits across study participants through Medicare, use of a previously validated measure of fragmentation, treatment of fragmentation as a time-varying exposure, adjudicated CHD events, and adjustment for clinically detailed potential confounders.

This study has several limitations. First, it is observational; we cannot rule out residual confounding or infer causation. Second, we did not have data on cardiac risk factor control over time, so we cannot directly test the hypothesized mechanisms above. Third, this study did not measure communication between providers, so the presence of fragmentation cannot be interpreted as the definite absence of communication. Fourth, self-rated health was measured at baseline and may change over time. However, self-rated health at baseline was a significant predictor of CHD events. Fifth, we were not able to account for whether physicians were in the same practice; if physicians practicing together had access to the same medical records, buffering potential harm from fragmentation, this would have biased our study toward the null.

In conclusion, among Medicare beneficiaries with very good or good self-rated health (which was two-thirds of the sample), highly fragmented ambulatory care was associated with an independent increase in the short-term risk of an incident CHD event. More research is needed to determine exactly how fragmentation contributed to this risk and to determine whether interventions are needed to reduce unnecessary fragmentation of care.

References

Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1130-9.

O'Malley AS, Reschovsky JD. Referral and consultation communication between primary care and specialist physicians: finding common ground. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:56-65.

Pham HH, O'Malley AS, Bach PB, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians' links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:236-42.

Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA 2005;293:565-71.

Kern LM, Seirup JK, Casalino LP, Safford MM. Healthcare fragmentation and the frequency of radiology and other diagnostic tests: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:175-81.

Romano MJ, Segal JB, Pollack CE. The Association Between Continuity of Care and the Overuse of Medical Procedures. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1148-54.

Hussey PS, Schneider EC, Rudin RS, Fox DS, Lai J, Pollack CE. Continuity and the costs of care for chronic disease. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:742-8.

Katz DA, McCoy KD, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS. Does Greater Continuity of Veterans Administration Primary Care Reduce Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization in Older Veterans? J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63:2510-8.

Liu CW, Einstadter D, Cebul RD. Care fragmentation and emergency department use among complex patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:413-20.

Nyweide DJ, Anthony DL, Bynum JP, et al. Continuity of care and the risk of preventable hospitalization in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1879-85.

van Walraven C, Oake N, Jennings A, Forster AJ. The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:947-56.

Kern LM, Seirup J, Rajan M, Jawahar R, Stuard SS. Fragmented ambulatory care and subsequent healthcare utilization among Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care 2018;24:e278-e84.

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018;137:e67-e492.

Linzer M, Myerburg RJ, Kutner JS, et al. Exploring the generalist-subspecialist interface in internal medicine. Am J Med 2006;119:528-37.

Howard VJ, Cushman M, Pulley L, et al. The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke study: objectives and design. Neuroepidemiology 2005;25:135-43.

Safford MM, Brown TM, Muntner PM, et al. Association of race and sex with risk of incident acute coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2012;308:1768-74.

**e F, Colantonio LD, Curtis JR, et al. Linkage of a populaton-based cohort with primary data collection to Medicare claims: The REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Am J Epidemiol 2016;184:532-44.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. HEDIS Volume 2: Technical Specifications, 2015. (Accessed May 22, 2020, at http://www.ncqa.org/HEDISQualityMeasurement/HEDISMeasures/HEDIS2015.aspx.)

Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care 1977;15:347-9.

Jee SH, Cabana MD. Indices for continuity of care: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:158-88.

Luepker RV, Apple FS, Christenson RH, et al. Case definitions for acute coronary heart disease in epidemiology and clinical research studies: a statement from the AHA Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; AHA Statistics Committee; World Heart Federation Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Epidemiology and Prevention; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation 2003;108:2543-9.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2012;126:2020-35.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. (Accessed May 22, 2020, at https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx.)

Gunzerath L, Faden V, Zakhari S, Warren K. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism report on moderate drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2004;28:829-47.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977;1:385-401.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604-12.

National Kidney Foundation. Albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). (Accessed May 22, 2020 at https://www.kidney.org/kidneydisease/siemens_hcp_acr.)

DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:267-75.

DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res 2005;40:1234-46.

DeSalvo KB, Fisher WP, Tran K, Bloser N, Merrill W, Peabody J. Assessing measurement properties of two single-item general health measures. Qual Life Res 2006;15:191-201.

Ware J, Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220-33.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Who is eligible for Medicare? 2020. (Accessed May 22, 2020, at https://www.hhs.gov/answers/medicare-and-medicaid/who-is-elibible-for-medicare/index.html.)

Kern LM, Seirup J, Rajan M, Jawahar R, Stuard SS. Fragmented ambulatory care and subsequent emergency department visits and hospital admissions among Medicaid beneficiaries. Am J Manag Care 2019;25:107-12.

Chang HG, Lininger LL, Doyle JT, Maccubbin PA, Rothenberg RB. Application of the Cox model as a predictor of relative risk of coronary heart disease in the Albany Study. Stat Med 1990;9:287-92.

Fisher LD, Lin DY. Time-dependent covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu Rev Public Health 1999;20:145-57.

Fleming TR, Harrington DP. Counting process and survival analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005.

Rubin DB, Schenker N. Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 1991;10:585-98.

Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol 2011;69:619-27.

Hays RD, Mallett JS, Haas A, et al. Associations of CAHPS Composites With Global Ratings of the Doctor Vary by Medicare Beneficiaries' Health Status. Med Care 2018;56:736-9.

Haime V, Hong C, Mandel L, et al. Clinician considerations when selecting high-risk patients for care management. Am J Manag Care 2015;21:e576-82.

Lustman A, Comaneshter D, Vinker S. Interpersonal continuity of care and type two diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:165-70.

Maciejewski ML, Hammill BG, Bayliss EA, et al. Prescriber Continuity and Disease Control of Older Adults. Med Care 2017;55:405-10.

Parchman ML, Pugh JA, Noel PH, Larme AC. Continuity of care, self-management behaviors, and glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Med Care 2002;40:137-44.

Younge R, Jani B, Rosenthal D, Lin SX. Does continuity of care have an effect on diabetes quality measures in a teaching practice in an urban underserved community? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012;23:1558-65.

Elliott WJ. Drug interactions and drugs that affect blood pressure. Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2006;8:731-7.

Guo JY, Chou YJ, Pu C. Effect of continuity of care on drug-drug interactions. Med Care 2017;55:744-51.

May M, Schindler C. Clinically and pharmacologically relevant interactions of antidiabetic drugs. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 2016;7:69-83.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wesley Jacobsson, BSc, for his assistance with the literature review. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the REGARDS study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating REGARDS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.regardsstudy.org.

Access to Data

Dr. Kern, Ms. Rajan, and Ms. Ringel had full access to the study data and take responsibility for the integrity of the analysis.

Funding

The REGARDS study is co-funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; the National Institute on Aging and the National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services (U01 NS041588). Adjudication for CHD events for REGARDS was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL080477). The ancillary study on healthcare fragmentation and cardiovascular outcomes was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL135199). The funding agencies played no role in the design or conduct of the study, and no role in data management, data analysis, interpretation of data, or preparation of the manuscript. The REGARDS Executive Committee reviewed and approved this manuscript prior to submission, ensuring adherence to standards for describing the REGARDS study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: Kern, Muntner, Casalino, Pesko, and Safford

Acquisition of data: Kern, Muntner, and Safford

Analysis and interpretation of the data: Kern, Rajan, Ringel, Colantonio, Muntner, Casalino, Pesko, Reshetnyak, Pinheiro, and Safford

Drafting of the manuscript: Kern

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Kern, Rajan, Ringel, Colantonio, Muntner, Casalino, Pesko, Reshetnyak, Pinheiro, and Safford

Statistical analysis: Rajan and Ringel

Obtained funding: Kern, Muntner, and Safford

Administrative, technical, or material support: Kern, Rajan, Ringel, Colantonio, Muntner, and Safford

Study supervision: Kern, Muntner, and Safford

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Dr. Kern is a consultant to Mathematica, Inc.

Ms. Rajan receives fees from the Veterans Biomedical Research Institute.

Dr. Safford receives grant funds from Amgen, Inc.

The other co-authors reported no conflicts

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM

(PDF 262 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kern, L.M., Rajan, M., Ringel, J.B. et al. Healthcare Fragmentation and Incident Acute Coronary Heart Disease Events: a Cohort Study. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 422–429 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06305-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06305-z