Abstract

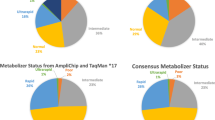

The AmpliChip™ CYP450 Test, which analyzes patient genotypes for cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, is a major step toward introducing personalized prescribing into the clinical environment. Interest in adverse drug reactions (ADRs), the genetic revolution, and pharmacogenetics have converged with the introduction of this tool, which is anticipated to be the first of a new wave of such tools to follow over the next 5–10 years. The AmpliChip™ CYP450 Test is based on microarray technology, which combines hybridization in precise locations on a glass microarray and a fluorescent labeling system. It classifies individuals into two CYP2C19 phenotypes (extensive metabolizers [EMs] and poor metabolizers [PMs]) by testing three alleles, and into four CYP2D6 phenotypes (ultrarapid metabolizers [UMs], EMs, intermediate metabolizers [IMs], and PMs) by testing 27 alleles, including seven duplications.

CYP2D6 is a metabolic enzyme with four activity levels (or phenotypes): UMs with unusually high activity; normal subjects, known as EMs; IMs with low activity; and PMs with no CYP2D6 activity (7% of Caucasians and 1–3% in other ethnic groups). Levels of evidence for the association between CYP2D6 PMs and ADRs are relatively reasonable and include systematic reviews of case-control studies of some typical antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Evidence for other phenotypes is considerably more limited. The CYP2D6 PM phenotype may be associated with risperidone ADRs and discontinuation due to ADRs. Venlafaxine, aripiprazole, duloxetine, and atomoxetine are newer drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 but studies of the clinical relevance of CYP2D6 genotypes are needed. Non-psychiatric drugs metabolized by CYP2D6 include metoprolol, tamoxifen, and codeine-like drugs.

CYP2C19 PMs (3–4% of Caucasians and African Americans, and 14–21% of Asians) may require dose adjustment for some TCAs, moclobemide, and citalopram. Other drugs metabolized by CYP2C19 are diazepam and omeprazole.

The future of pharmacogenetics depends on the ability to overcome serious obstacles, including the difficulties of conducting and publishing studies in light of resistance from grant agencies, pharmaceutical companies, and some scientific reviewers. Assuming more studies are published, pharmacogenetic clinical applications may be compromised by economic factors and the lack of physician education. The combination of a US FDA-approved test, such as the AmpliChip™ CYP450 Test, and an FDA definition of CYP2D6 as a ‘valid biomarker’ makes CYP2D6 genoty** a prime candidate to be the first successful pharmacogenetic test in the clinical environment. One can use microarray technology to test for hundreds of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) but, taking into account the difficulties for single gene approaches such as CYP2D6, it is unlikely that very complex pharmacogenetic approaches will reach the clinical market in the next 5–10 years.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. JAMA 1998; 279: 1200–5

Bordet R, Gautier S, Le Louet H, et al. Analysis of the direct cost of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 56: 935–41

Lacoste-Roussillon C, Pouyanne P, Haramburu F, et al. Incidence of serious adverse drug reactions in general practice: a prospective study. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001;69: 458–62

Lundkvist J, Jonsson B. Pharmacoeconomics of adverse drug reactions. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2004; 18: 275–80

Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet 2000; 356: 1255–9

Pirmohamed M, Breckenridge AM, Kitteringham NR, et al. Adverse drug reactions. BMJ 1998; 316: 1295–8

Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, et al. Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. JAMA 1997; 277: 301–6

Institute of Medicine: To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academic Press, 2000

Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, et al. Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA 2002 May 1; 287(17): 2215–20

Johnson JA, Bootman JL. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: a cost-of-illness model. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 1949–56

Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharm Assoc 2001; 41: 192–9

Chou WH, Yan FX, de Leon J, et al. An extension of a pilot study: impact from the cytochrome P450-2D6 (CYP2D6) polymorphism on outcome and costs in severe mental illness. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20: 246–51

Collins FS, Green ED, Guttmacher AE, et al. A vision for the future of genomics research. Nature 2003; 422: 835–7

Gibbs N. The secret of life. Time 2003 Feb 17; 161(7): 42–5

McKusick VA. The anatomy of the humane genome: a neo-vesalian basis for medicine in the 21st century. JAMA 2001; 286: 2289–95

Fodor SP. Massively parallel genomics. Science 1997; 277: 393–5

Chaudhuri JD. Gene arrays out of you: the amazing world of microarrays. Med Sci Monit 2005; 11: RA52–62

Emery J, Hayflick S. The challenge of integrating genetic medicine into primary care. BMJ 2001; 322: 1027–30

Hammer W, Sjoqvist F. Plasma levels of monomethylated tricyclic antidepressants during treatment with imipramine-like compounds. Life Sci 1967; 6: 1895–903

Phillips KA, Veenstra DL, Oren E, et al. Potential role of pharmacogenomics in reducing adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. JAMA 2001; 286: 2270–9

Vogel F. Moderne probleme der Humangenetik. Ergeb Inn Med Kinderheilkd 1959; 12: 52–125

Pirmohamed M. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics. J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 52: 345–7

Editor: new research horizons. Science 1997; 278: 2039

Lertola J. Deciphering the code and what might come from it. Time 1999 Nov 8; 68-9

Collins FS, McKusick VA. Implications of the human genome project for medical science. JAMA 2001; 285: 540–4

Pirazzoli A, Recchia G. Pharmacogenetics and pharmacogenomics: are they still promising? Pharmacol Res 2004; 49: 357–61

Nebert DW, Jorge-Nebert L, Vesell ES. Pharmacogenomics and “individualized drug therapy”: high expectations and disappointing achievements. Am J Pharmacogenomics 2003; 3: 361–70

Ingelman-Sundberg M. Human drug metabolising cytochrome P450 enzymes: properties and polymorphisms. Naunyan Schmiedbergs Arch Pharmacol 2004; 369: 89–104

Ingelman-Sundberg M. Genetic polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6): clinical consequences, evolutionary aspects and functionary diversity. Pharmacogenomics J 2005; 5: 6–13

Mahgoub A, Idle JR, Dring LG, et al. Polymorphic hydroxylation of debrisoquine in man. Lancet 1977; II(8038): 584–6

Eichelbaum M, Spannbrucker N, Dengler HJ. Influence on the defective metabolism of sparteine on its pharmacokinetics. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 16: 189–94

Skoda RC, Gonzalez FJ, Demierre A, et al. Two mutant alleles of the human cytochrome P-450db1 gene (P450C2D1) associated with genetically deficient metabolism of debrisoquine and other drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988; 85: 5240–3

Heim M, Meyer UA. Genoty** of poor metabolisers of debrisoquine by allele-specific PCR amplification. Lancet 1990; 336: 529–32

Bertilsson L, Dahl ML, Sjoqvist F, et al. Molecular basis for rational megaprescribing in ultrarapid hydroxylators of debrisoquine. Lancet 1993; 341: 63

Johansson I, Oscarson M, Yue QY, et al. Genetic analysis of the Chinese cytochrome P4502D locus: characterization of variant CYP2D6 genes present in subjects with diminished capacity for debrisoquine hydroxylation. Mol Pharmacol 1994; 271: 1250–7

Chou WH, Yan FX, Robbins-Weilert DK, et al. Comparison of two CYP2D6 genoty** methods and assessments of genotype-phenotype relationships. Clin Chem 2003; 49: 542–51

Lovlie R, Daly AK, Matre GE, et al. Polymorphisms in CYP2D6 duplicationnegative individuals with the ultrarapid metabolizer phenotype: a role for the CYP2D6*35 allele in ultrarapid metabolism? Pharmacogenetics 2001; 11: 45–55

Kirchheiner J, Nickchen K, Bauer M, et al. Pharmacogenetics of antidepressants and antipsychotics: the contribution of allelic variations to the phenotype of drug response. Mol Psychiatry 2004; 9: 442–73

deLeon J, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. Clinical guidelines for psychiatrists for the use of pharmacogenetic testing for CYP450 2D6 and CYP450 2C19. Psychoso-matics 2006; 47: 75–85

Arthur H, Dahl ML, Siwers B, et al. Polymorphic drug metabolism in schizophrenic patients with tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995; 15: 211–6

Armstrong M, Daly AK, Blennerhassett R, et al. Antipsychotic drug-induced movement disorders in schizophrenics in relation to CYP2D6 genotype. Br J Psychiatry 1997; 170: 23–6

Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Sweet RA, et al. Prospective cytochrome P450 phenoty** for neuroleptic treatment in dementia. Psychopharmacol Bull 1995; 31: 327–32

Bork J, Rogers T, Wedlund P, et al. A pilot study of risperidone metabolism: the role of cytochrome P450 2D6 and 3A. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60: 469–76

Bertilsson L, Aberg-Wistedt A, Gustafsson LL, et al. Extremely rapid hydroxylation of debrisoquine: a case report with implication for treatment with nortriptyline and other tricyclic antidepressants. Ther Drug Monit 1985; 7: 478–80

Chen S, Chou W, Blouin R, et al. Clinical and practical aspects to screening for the cytochrome P450-2D6 (CYP2D6) enzyme polymorphism. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1996; 60: 522–34

Krau RP, Diaz P, McEachran A. Managing rapid metabolizers of antidepressants. Depress Anxiety 1996–1997; 4: 320–7

Spina E, Gitto C, Avenoso A, et al. Relationship between plasma desipramine levels, CYP2D6 phenotype and clinical response to desipramine: a prospective study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1997; 51: 395–8

Meyer JW, Woggon B, Küpfer A. Importance of oxidative polymorphism on clinical efficacy and side-effects of imipramine: a retrospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry 1988; 21: 365–6

Kirchheiner J, Brøsen K, Dahl ML, et al. CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyped-based recommendations for antidepressants: a first step towards subpopulation-specific dosages. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001; 104: 173–92

Kirchheiner J, Bertilsson L, Brass H, et al. Individualized medicine: implementation of pharmacogenetic diagnostics antidepressant drag treatment of major depressive disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry 2003; 36(3 Suppl.): S235–43

deLeon J, Barnhill J, Rogers T, et al. A pilot study of the cytochrome P450-2D6 genotype in a psychiatric state hospital. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155: 1278–80

Huang M, VanPeer A, Woestenborghs R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of the novel antipsychotic agent risperidone and the prolactin response in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1993; 54: 257–68

deLeon J, Bork JA. Risperidone and the cytochrome P450 3A [letter]. J Clin Psychiatry 1997; 58: 450

Fang J, Bourin M, Baker GB. Metabolism of risperidone to 9-hydroxyrisperidone by human cytochromes P450 2D6 and 3A4. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1999; 359: 147–51

Cappell K, Arndt M, Carey J. Drags get smart. Business Week 2005 Sep 5; 76-85

Emens LA. Trastuzumab: targeted therapy for the management of HER-2/neuoverexpressing metastatic breast cancer. Am J Ther 2005; 12: 243–53

Adams GP, Weiner LM. Monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Biotechnol 2005; 23: 1147–57

Iyer L. Inherited variations in drug-metabolizing enzymes: significance in clinical oncology. Mol Diagn 1999; 4: 327–33

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA clears genetic test that advances personalized medicine: test helps determine safety of drug therapy [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2005/NEW01220.html [Accessed 2005 Oct 17]

MacArthur RD. An updated guide to genotype interpretation. AIDS Read 2004; 14: 256–8, 261-4, 266

Sturmer M, Doerr HW, Preiser W. Variety of interpretation systems for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genoty**: confirmatory information or additional confusion? Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord 2003; 3: 373–82

deLeon J, Susce MT, Pan RM. The CYP2D6 poor metabolizer phenotype may be associated with risperidone adverse drug reactions and discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 15–27

Barnhill J, Susce MT, Diaz FJ, et al. Risperidone half-life in a patient taking paroxetine: a case report [letter]. Pharmacopsychiatry 2005; 38(5): 223–5

Wang JS, Ruan Y, Taylor RM, et al. The brain entry of risperidone and 9-hydroxyrisperidone is greatly limited by p-glycoprotein. Int J Neurop-sychopharmacol 2004; 7: 415–9

Tyndale RF, Droll KP, Sellers EM. Genetically deficient CYP2D6 metabolism provides protection against oral opiate dependence. Pharmacogenetics 1997; 7: 375–9

deLeon J, Dinsomore L, Wedlund PJ. Adverse drug reactions to oxycodone and hydrocodone in CYP2D6 ultrarapid metabolizers [letter]. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003; 23: 420–1

Wuttke H, Rau T, Heide R, et al. Increased frequency of cytochrome P450 2D6 poor metabolizers among patients with metoprolol-associated adverse effects. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 72: 429–37

** Y, Desta Z, Stearns V, et al. CYP2D6 genotype, antidepressant use, and tamoxifen metabolism during adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 30–9

Wedlund PJ. The CYP2C19 enzyme polymorphism. Pharmacology 2000; 6: 174–85

Furuta T, Ohashi K, Kamata T, et al. Effect of genetic differences in omeprazole metabolism on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer. Ann Intern Med 1998; 129: 1027–30

Steimer W, Zoph K, Von Amelunxen S, et al. Amitriptyline or not, that is the question: pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 identifies patients with low or high risk for side effects in amitriptyline therapy. Clin Chem 2005; 51: 376–85

Daly AK. Development of analytical technology in pharmacogenetic research. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2004; 369: 133–40

Roche Molecular Systems Inc. AmpliChip CYP450 Test for in vitro diagnostic use [equivalent to the package insert]. Branchburg (NJ): Roche Molecular Systems Inc., 2005

Ensom MH, Chang TK, Patel P. Pharmacogenetics: the therapeutic drug monitoring of the future? Clin Pharmacokinet 2001; 40: 783–802

Touw DJ, Neef C, Thomson AH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring: a systematic review. Ther Drug Monit 2005; 27: 10–7

Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: papers that report diagnostic or screening test. BMJ 1997; 315: 540–3

Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association. Special report: genoty** for cyto-chrome P450 polymorphisms to determine drug-metabolizer status [online]. Technical Assessment Program 2004 Dec; 19 (9). Available from URL: http://www.bcbs.com/tec/voll9/19._09.pdf [Accessed 2005 Sep 13]

Bortolin S, Black M, Modi H, et al. Analytical validation of the Tag-It high throughput microsphere-based universals array genoty** platform: application to the multiplex detection of a panel of thrombophilia-associated single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Clin Chem 2004; 50: 2028–36

Wolf CR, Smith G, Smith RL. Science, medicine, and the future: pharmacogenetics. BMJ 2000; 320: 987–90

Weinshilboum R, Wang L. Pharmacogenomics: bench to bedside. Nat Rev 2004; 3: 739–48

Pharmacogenomics to come [editorial]. Nature 2003; 425: 749

Inouye SK, Fiellin D. An evidence-based guide to writing grant proposals for clinical research. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 274–82

deLeon J, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. Med-psych drug-drug interaction update: the dosing of atypical antipsychotics. Psychosomatics 2005; 46: 262–73

Sadee W. Pharmacogenomics: the implementation phase. AAPS PharmSci 2002; 4(2): E5.

Kerwin RW. A perspective on progress in pharmacogenomics. Am J Pharmacogenomics 2003; 3: 371–3

Danzon P, Towse A. The economics of gene therapy and of pharmacogenetics. Value Health 2002; 5: 5–13

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Drug-diagnostic co-development: concept paper [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/genomics/pharmacoconceptfn.pdf [Accessed 2005 Jun 10]

Gill CJ, Sabin L, Schmid CH. Why clinicians are natural Bayesians. BMJ 2005; 330: 1080–3

Botts S, Littrell R, de Leon J. Variables associated with high olanzapine dosing in a state hospital. J Clin Psychiatry 2004; 65: 1138–43

Choudry NT, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 260–73

Gurtwitz D, Weizman A, Rehavi M. Education: teaching pharmacogenomics to prepare future physicians and researchers for personalized medicine. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2003; 24: 122–5

Alfaro CL, Lam YW, Simpson J, et al. CYP2D6 status of extensive metabolizers after multiple-dose fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1999; 19: 155–63

Susce MT, Murray-Carmichael E, de Leon J. Response to hydrocodone, codeine and oxycodone in a CYP2D6 poor metabolizer. Prog NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2006 Apr 20; [Epub ahead of print].

Kirchheiner J, Brockmoller J. Clinical consequences of cytochrome P450 2C9 polymorphisms. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2005; 77: 1–16

Veenstra DL, Higashi MK. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of pharmacogenomics. AAPS Pharmsci 2000; 2: 1–11

Corominas H, Baiget M. Clinical utility of thiopurine S-methyltransferase genoty**. Am J Pharmacogenomics 2004; 4: 1–8

Ruano G. Quo vadis personalized medicine. Personalized Med 2004; 1: 1–7

Wedlund PJ, deLeon J. Pharmacogenetic testing: the cost factor. Pharmacogenomics J 2001; 1: 171–4

Acknowledgments

The genoty** studies of psychiatric patients included in this article were conducted at the University of Kentucky Mental Health Research Center at Eastern State Hospital, Lexington, Kentucky, USA.

Jose de Leon, M.D., has received support for his laboratory and research-initiated grants and honoraria from Roche-Molecular Systems, Inc., but has not received any consultant payments and has no other financial arrangements with Roche Molecular Systems, Inc. He has no stocks from Roche or Affymetrix. Dr de Leon has also served on an advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, and has received researcher-initiated grants and honoraria from Eli Lilly. Many of the ideas presented in this article are the distillation of years of discussion and collaboration of Jose de Leon with Dr Walter Koch. The authors thank Lorraine Maw, Tita Forrest and Michele Nikoloff for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Leon, J., Susce, M.T. & Murray-Carmichael, E. The AmpliChip™ CYP450 Genoty** Test. Mol Diag Ther 10, 135–151 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256453

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256453