Abstract

Background

Outcomes of unplanned excisions of extremity soft tissue sarcomas (STSE) range from poor to even superior compared with planned excisions in developed countries. However, little is known regarding outcomes in low-to-middle-income countries. This study aimed to determine whether definitively treated STSE patients with a previous unplanned excision have poorer oncologic outcomes compared with those with planned excisions.

Patients and Methods

Using the database of a single sarcoma practice, we reviewed 148 patients with STSE managed with definitive surgery-78 with previous unplanned excisions (UE) and 70 with planned excisions (PE).

Results

Median follow-up was 4.4 years. UE patients had more surgeries overall and plastic reconstructions (P < 0.001). On multivariate analysis, overall survival (OS), local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were not worse among UE patients compared with PE patients. Negative predictors for LRFS were high tumor grade (P = 0.031) and an R1 surgical margin (P < 0.001). High grade (P <0.001), local recurrence (P = 0.001), and planned excisions (P = 0.009) predicted poorer DMFS, while age over 65 years (P = 0.011) and distant metastasis predicted poorer OS (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

We recommend systematic re-excision for patients with unplanned excisions. Our study shows that STSE patients with UE, when subjected to re-excision with appropriate surgical margins, can achieve oncologic results similar to those for PE patients. However, there is an associated increased number of surgeries and plastic reconstruction for UE patients. This underscores the need, especially in a resource-limited setting, for education and collaborative policies to raise awareness about STSE among patients and physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Unplanned excision (UE) of soft tissue sarcomas refers to surgical removal of the tumor without awareness of its malignant nature. There is often a lack of appropriate diagnostic and staging examinations and a consequent resection oblivious to the oncologic margins recommended for sarcomas, resulting in what is also known as “whoops surgeries”.1,2

Most UEs are attributed to both the low prevalence and the accompanying lack of awareness of soft tissue sarcomas.2 After initial UE, these patients are referred to sarcoma centers where they undergo further wide or radical resections with or without adjuvant treatment. The literature, however, has been inconsistent regarding patient outcomes. Reported oncologic results range from poor to even superior compared with planned excisions (PE).3,4,5 In addition, most studies addressing UE of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities (STSE) come from developed countries; few have been reported from low-to-middle-income countries (LMIC)3,6,7 such as the Philippines, where patients can ill-afford the additional costs of repeat surgeries.

In this study, we describe the prevalence and demographics of patients with UE referred to a sarcoma practice in the Philippine General Hospital, and compare oncologic outcomes with those of patients undergoing standard PE. Risk factors for local recurrence (LR), distant metastasis (DM), and overall survival (OS) were also determined.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

This study was approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Ethics Review Board. We conducted a retrospective cohort review using the tumor database of a single sarcoma practice at the University of the Philippines–Philippine General Hospital over a period of 25 years (1994–2018). This practice includes the specialties of orthopedic, radiation, medical and pediatric oncology, and musculoskeletal tumor pathology.

Patients who had histologically confirmed STSE managed with definitive surgery with or without adjuvant treatment were included. We excluded patients who had documented metastasis on presentation, were referred for nonsurgical management, did not have a minimum 2-year follow-up in the absence of demise, and those with a histologic diagnosis of atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma (ALT/WDLS) or dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) due to their more favorable prognosis.

The database included patient demographic information, tumor, and treatment variables. Sources of data were hospital records, operation reports, imaging and histopathology reports, and out-patient records. Histologic diagnosis was ascertained by submitting available slides and paraffin blocks for review and additional immunohistochemical staining if further recommended by our pathologists.

Patients were divided into two groups based on initial treatment: unplanned excisions (UE group) and planned excisions (PE group). UE was defined as the removal of sarcoma without regard for appropriate surgical margins, including incomplete resection, open biopsy using a wrong biopsy tract, excisions with tumor contamination that would be otherwise preventable, and inappropriate drain placement. This group of patients went on to receive definitive surgery at our unit. All UE patients underwent re-excision because of contaminated margins, corroborated by histologic review, surgical records, and/or communication with referring physicians. On the other hand, the PE group included patients with no history of a previous inappropriate surgery and underwent standard treatment at our unit.

On presentation at clinic, all patients underwent local and systemic staging studies, including histopathologic confirmation with either a biopsy or a review of slides and/or paraffin block with or without immunohistochemical stains. Wide resection with or without radiotherapy was the standard of treatment. If neoadjuvant radiotherapy was given, surgery was scheduled 4–6 weeks after. Postoperative radiotherapy was given based on the surgical pathology report and surgeon discretion. Chemotherapy was not part of standard treatment unless patients developed metastasis. In UE patients presenting without a macroscopic mass, wide margins were obtained by excising at least 2 cm around the prior incision and all areas exposed during the previous surgery as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A positive margin was reported when either tumor (microscopic or macroscopic) was present at the surgical margin or the surgeon documented a contaminated margin during attempted wide excision, i.e., inadvertent entry into tumor capsule and/or tumor spillage. The presence of residual tumor (ReT) in surgical scar excision specimens from the UE group was also recorded. Posttreatment surveillance included a follow-up every 3 months with chest radiographs alternating with chest computed tomography (CT) scans for 2–3 years, followed by a follow-up every 6 months in years 4 and 5, with annual follow-up thereafter until year 10.

Primary outcomes measured were OS, distant metastasis free survival (DMFS), and local recurrence free survival (LRFS). Secondary outcomes included total number of excisions (prior to and at our hospital), reconstructive procedures (including skin grafts, flaps, tendon, or bone work), re-operations at our hospital, and treatment complications.

Statistical Analysis

Means between the two treatment groups were analyzed and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables (age, tumor size) while the Fisher’s exact tests and Chi square tests were used to determine the associations between categorical variables. Bivariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were done to estimate the hazard ratios for the association of patient-, tumor-, and treatment-related factors with overall survival, metastasis, and local recurrence. Adjusted hazard ratios and their 95% confidence intervals relating the exposure variables and OS, DM, and LR were presented. All data management and statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp 2019).

Results

We identified 274 patients with STSE from the database. We excluded 18 patients who did not undergo further surgery at the unit, 40 who did not meet minimum follow-up, 37 with missing data, 16 with a diagnosis of ALT/WDLS or DFSP, and 15 who were metastatic on presentation (9 in PE; 6 in UE). Hence, a total of 148 patients were included in the analysis: 70 PE and 78 UE.

Table 1 summarizes patient demographic and clinical characteristics. The median follow-up time was 4.4 years (range 0.3–27.3 years). The most common tumor histologies were malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (19%), liposarcoma (17%), undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (13%), and synovial sarcoma (10%). The majority of patients (60%) had high-grade tumors. Sixty-nine patients (46%) received radiotherapy, with 16 receiving neoadjuvant radiotherapy. Only 26 patients (18%) received chemotherapy. On latest follow-up, 77 patients were alive with no evidence of disease (ANED), 17 had evidence of disease (AWED), 39 were dead of disease (DOD), while 15 had died from unrelated causes (DOC).

Sixty-nine percent of UE patients had high-grade tumors compared with 50% in PE patients (P = 0.017). Both UE and PE groups had more deep than superficial tumors. The frequency of superficial tumors in the UE group was almost twice that in the PE group, but this fell slightly short of statistical significance (P = 0.058). Treatment characteristics (radiotherapy, chemotherapy, margin status) of both groups did not differ significantly.

Secondary outcomes between groups are presented in Table 2. The total number of surgeries and reconstruction rate were significantly higher in the UE group (P < 0.001). The average number of reconstructive procedures in the UE patients was three times that in the PE group (P < 0.001). In addition, the mean number of surgeries of UE patients was 2.7 while that of PE patients was only 1.6 (P < 0.001).

A Cox regression model was used to determine factors associated with clinical outcomes of patients adjusted for all other factors in the full model (Table 3).

The cumulative mortality rate over a median follow-up time of 4 years was 36.5% (95% CI 28.7–44.8%). The 5-year OS was 67% (95% CI 59.0–75.0%) and the 10-year OS was 58% (95% CI 48.6–66.9%). Bivariate analyses show that factors associated with the OS of surgically treated primary STS patients include age and development of DM. The risk of mortality among patients 65 years or older was 2.7 times the risk in those less than 65 years old (aHR, 2.7; 95% CI 1.3–5.9; P = 0.011); the difference being at 10-year follow-up where the survival rate of the 65+ age group decreases by almost half. Significantly, the risk of mortality in those develo** DM was 10.8 times the risk in those who did not (aHR, 10.8; 95% CI, 5.1–22.6; P < 0.001). The risk of mortality among those who had UE was lower than those receiving PE (aHR, 0.6; 95% CI 0.3–1.0; P = 0.054) although this difference was not significant.

The 5-year LRFS was 77% (95% CI, 69.6–84.9%) while the 10-year LRFS was 71% (95% CI, 61.2–80.1%). On Cox regression analysis, only an R1 margin (aHR, 13.6; 95% CI, 5.4–34.1; P < 0.001) and high tumor grade (aHR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.1–10.4; P = 0.031) were found to be negative predictors.

We report a 5-year DMFS of 65% (95% CI, 57.0–73.5%) and a 10-year DMFS of 58% (95% CI, 48.1–67.6%). Multivariate analysis showed the following to be negative predictors for distant metastasis: high grade (aHR, 4.5; 95% CI, 2.0–10.2; P < 0.001) and local recurrence (aHR, 2.9; 95% CI, 1.5–5.6; P = 0.001). PE was a negative predictor for DMFS (aHR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.8; P = 0.009).

Among UE patients, 27/78 (35%) presented with post-excisional scars alone. Their index surgeries either had a positive margin on slide review (26 of 27 patients) or were marginal resections as corroborated by the referring surgeon (1 of 27 patients). These 27 patients were subjected to a wide excision of the scar including the previous surgical cavity. In 24 of these 27 patients with available histopathology documentation following scar excision, 58% (14/24) of excised scar specimens had microscopic ReT (Table 4). None of the ten patients without residual tumor developed local or distant recurrence and none were DOD on latest follow-up. Patients with microscopic ReT had the highest rate of DM compared with those with macroscopic residual and the PE group.

Discussion

After Guiliano,8 Hays,9 and Zornig10 first alerted us to UE of STSE, there have been many studies evaluating the effect of UE on patient oncologic outcomes.1,3,4,5,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22

To address the problems of residual tumor and inadequate oncologic margins, re-excision has become standard treatment, often accompanied by reconstructive surgery with or without adjuvant radiation.23 These additional procedures are a burden to both patient and health care provider, especially in resource-limited LMICs such as the Philippines. Recent concern has been raised about the rising number of UE referrals to sarcoma units nationwide (private communications), including the last 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic. We recognize this study as an important step**stone to establish the burden of the problem, describe its clinical consequences, and better comprehend treatment options with a view to improve referral pathways for STSE management.24,25,26

In this 25-year cohort of patients from a single sarcoma practice at the University of the Philippines–Philippine General Hospital, we report a high cumulative referral incidence for UE of 52% of all surgically treated STSE. In two separate reviews, Grimer2 and Sachetti23 note that UE accounted for 18–66% of STS referrals to sarcoma centers. Index surgeries in our UE group were performed by non-sarcoma surgeons, usually without the benefit of biopsy or imaging studies and often with surgical incisions and placement of drains lacking consideration for tumor contamination.

Comparison Between PE and UE Patients

The PE and the UE groups were comparable across patient and tumor variables except for size, presence of tumor mass, and grade. Differences in size and presence of a mass were because the gross tumor has been resected, albeit incompletely in UE patients. Masses in UE patients were due to either recurrent or residual tumor.

There was a significantly higher percentage of high-grade STSE among UE versus PE patients (50% versus 69.2%; P = 0.017). Many studies describe a similarly greater proportion of high-grade tumors among UE patients, ranging from 69% to 95%.14,17,22,24,27 Chandrasekar et al.18 noted a higher rate of LR among high-grade tumors and those excised with close surgical margins; similar to the findings of this study where both variables are negative predictors for LR. These observations may explain the larger number of high-grade tumors on presentation among the UE group.

We observed a higher proportion of superficial tumors in the UE compared with the PE group and that almost two-thirds of all patients with superficial STSE had initially undergone UE. This corroborates the expectation that because surgeons are prompted to refer large and deep masses, many inadvertently excised masses would then be superficial and small.1,3,5,6,10,14,24 Presentation of superficial lesions may be similar to other more common benign soft tissue masses and may seem tempting and easy to remove.

In terms of type of surgery (limb saving or amputation) received, adjuvant therapies, and postoperative complication rates, there was no significant difference between UE and PE patients. However, the UE group underwent significantly more surgeries (1.6 versus 2.7, P < 0.001) and more reconstructive procedures (17.1 versus 51.3, P < 0.001). This is to be expected as all UE patients underwent re-excision and many required plastic reconstructions to cover the soft tissue defects resulting from the additionally wide surgical margins during re-excision. Mesko et al.13 reported that 74% of patients in their UE group required a major alteration in their definitive wide margin surgical resection, including rotational muscle or free flap coverage and amputation.

Evaluation of Entire Cohort for Possible Prognosticators of Oncologic Outcomes

Variables that were negative predictors on multivariate analysis for local recurrence included positive or R1 surgical margin (13.6 times increase) and high histologic grade (3.4 times increase). Many previous studies have consistently shown the strong association between R1 margins and local recurrence,4,5,16,17,19 while Chandrasekar.18 also reported both R1 margin and high histologic grade as negative predictors for local recurrence.

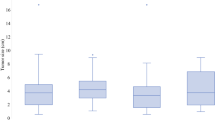

Similar to reports by Charoenlap,1 Zagars,19 and Lewis,4 we found an increase in the rate of distant metastasis (4.5 times) for patients with tumors of high histologic grade and for patients who developed local recurrence (2.9 times). On the other hand, the presence of distant metastasis increased the risk of mortality by 10.8 times. Aggressive tumor biology and natural course of the disease most likely underlie these associations of distant metastasis with high grade and local recurrence, and of poorer overall survival with distant metastasis. But the associations of UE with better overall survival, even if marginally significant, and a lower risk of distant metastasis seem counter intuitive (Fig. 1).

Similar results have been reported by Lewis et al.4 where improved survival was shown in UE patients who underwent re-excision and by Bianchi et al.5 where UE/re-excision was determined to be a prognosticator on multivariate analysis for better sarcoma-specific survival, local recurrence-free survival, and distant metastasis -free survival. One reason to explain these results is selection bias: larger tumors located in more difficult locations having a greater chance of being directly referred to a sarcoma unit,7,10,14,15,26 while smaller, more easily accessible tumors are more prone to UE by a nonsuspecting surgeon. Indeed, we had a bigger proportion of superficial tumors among our UE group. The apparent favorable results may have contributed to the suggestion that “two excisions are better than one,” referring to the increased chances of removing histologically undetectable tumor.4 Of course, our exclusion criteria of metastatic patients on presentation may have already excluded UE patients with more aggressive tumors. Danielli et al.22 also suggested that the time elapsed between UE and re-excision may also have selected patients with better prognosis.

Residual Tumor (ReT) and the Need for Re-excision

Residual tumor has been shown to be prognostic for poorer local control, distant metastasis, and even overall survival.1,12,16,18 At our unit, all UE patients underwent re-excision; whether of the macroscopic ReT or of the excision scar together with the previous surgical cavity. In the latter group, 58% (14/24) had microscopic ReT (Table 4), well within the range of 35–91% reported in literature.23 Interestingly, among patients without microscopic ReT, none died of disease or developed LR or DM. These ten patients without ReT would have contributed to the seemingly favorable oncologic results of the UE group.

Based on the above evaluation, re-excision using wide surgical oncologic margins is recommended for all patients who have received UE because there is no way to predict presence of residual tumor in scars. Our own data records microscopic tumor presence in almost 60% of scar tissue excised. Bianchi et al.5 notes that re-excision guarantees oncologic outcomes similar to patients primarily treated at their center. Zagar et al.19 evaluating 666 localized STS patients, reported that UE patients who did not undergo re-excision in their institution had significantly lower 5-year LRFS (P = 0.03) and DMFS (P = 0.008) than those who underwent re-excision. The meta-analysis by Sacchetti et al.23 estimates a LR rate of at least 50% since ReT is present on the average in 58% (35–91%) of excised specimens.

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature. In this sarcoma service, the basic management protocol for STSE patients in particular, whether referred as UE or PE, has remained the same throughout the 25 years, i.e., after appropriate diagnostic and screening examinations, they are all subjected to re-excisions, perioperative neoadjuvant, or adjuvant treatment as necessary and uniform postoperative follow-up and surveillance. The changes in these 25 years would likely be streamlining of referral processes both within and external to the service and the continuing improvement of sarcoma expertise among the different subspecialties of the team. Given the relatively small population, we could not differentiate among different histologies and may have missed out on tumor characteristics peculiar to certain subtypes. We also could not do baseline propensity scoring.

Conclusions

Fifty-two percent of STSE patient referrals to our sarcoma unit present as unplanned excisions or whoops surgeries; among which there was a higher proportion of high-grade and superficial tumors. Our study shows UE patients undergo more surgeries and reconstructive procedures, but overall survival is not worse compared with that of PE patients. We continue to advocate for routine re-excision in UE patients because (1) re-excision provides a second opportunity for UE patients to achieve oncologic outcomes equal to PE patients, (2) given the high rate of residual tumor presence after UE, and (3) multivariate analysis shows close association among contaminated surgical margins, local recurrence, distant metastasis, and poor overall survival.

Few LMICs have described the issue of unplanned excisions with no previous report from Southeast Asia, making this the first study to do so. In this context, it is important to note the increased number of surgeries and plastic reconstructions among the UE group as these translate into additional health care resource utilization. This financial burden together with potentially poor oncologic outcomes if UE patients are not subjected to re-excision emphasizes the urgent need for education and advocacy campaigns to raise awareness about STS among both frontline physicians and patients themselves. Direct referral to a sarcoma center still provides the best results.28 At the same time, a collaborative sarcoma program involving referral centers, training institutions, professional societies, and government agencies can best support these initiatives.13,25,26

References

Charoenlap C, Imanishi J, Tanaka T, et al. Outcomes of unplanned sarcoma excision: impact of residual disease. Cancer Med. 2016;5(6):980–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.615.

Grimer R, Parry M, James S. Inadvertent excision of malignant soft tissue tumours. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(6):321–9. https://doi.org/10.1302/2058-5241.4.180060.

Umer HM, Umer M, Qadir I, Abbasi N, Masood N. Impact of unplanned excision on prognosis of patients with extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Sarcoma. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/498604.

Lewis JJ, Leung D, Espat J, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Effect of reresection in extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2000;231(5):655–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-200005000-00005.

Bianchi G, Sambri A, Cammelli S, et al. Impact of residual disease after “unplanned excision” of primary localized adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities: evaluation of 452 cases at a single institution. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(3):243–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-017-0475-y.

Alyaf S, Dev K, Gurawalia J, Kurpad V, Pandey A. The burden of unplanned excision of soft tissue tumours in develo** countries: a 10-years’ experience at a regional cancer centre. Arch Cancer Res. 2016. https://doi.org/10.21767/2254-6081.1000105.

Hanasilo C, Casadei M, Auletta L, Amstalden E, Matte S, Etchebehere M. Comparative study of planned and unplanned excisions for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma of the extremities. Clinics. 2014;69(9):579–84. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2014(09)01.

Giuliano AE, Eilber FR. The rationale for planned reoperation after unplanned total excision of soft-tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol. 1985;3(10):1344–8.

Hays DM, Lawrence W, Wharam M, et al. Primary reexcision for patients with ‘microscopic residual’ tumor following initial excision of sarcomas of trunk and extremity sites. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24(1):5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80290-8.

Zornig C, Peiper M, Schroder S. Re-excision of soft tissue sarcoma after inadequate initial operation. Br J Surg. 2005;82(2):278–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800820247.

Smolle MA, Tunn PU, Goldenitsch E, et al. The prognostic impact of unplanned excisions in a cohort of 728 soft tissue sarcoma patients: a multicentre study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(6):1596–605. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-017-5776-8.

Fiore M, Casali PG, Miceli R, et al. Prognostic effect of re-excision in adult soft tissue sarcoma of the extremity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(1):110–7. https://doi.org/10.1245/ASO.2006.03.030.

Mesko NW, Wilson RJ, Lawrenz JM, et al. Pre-operative evaluation prior to soft tissue sarcoma excision – why can’t we get it right? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(2):243–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.11.001.

Nakamura T, Kawai A, Sudo A. Analysis of the patients with soft tissue sarcoma who received additional excision after unplanned excision: report from the bone and soft tissue tumor registry in Japan. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2017;47(11):1055–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyx123.

Nakamura T, Kawai A, Hagi T, Asanuma K, Sudo A. A comparison of clinical outcomes between additional excision after unplanned and planned excisions in patients with soft-tissue sarcoma of the limb. Bone Joint J. 2021;103-B(12):1809–14. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.103B12.BJJ-2021-0037.R1.

Arai E, Sugiura H, Tsukushi S, et al. Residual tumor after unplanned excision reflects clinical aggressiveness for soft tissue sarcomas. Tumor Biol. 2014;35(8):8043–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13277-014-2043-5.

Han I, Kang HG, Kang SC, Choi JR, Kim HS. Does delayed reexcision affect outcome after unplanned excision for soft tissue sarcoma? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;469(3):877–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-010-1642-8.

Chandrasekar CR, Wafa H, Grimer RJ, Carter SR, Tillman RM, Abudu A. The effect of an unplanned excision of a soft-tissue sarcoma on prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2008;90(2):90–203. https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.90B2.

Zagars GK, Ballo MT, Pisters PWT, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with localized soft-tissue sarcoma treated with conservation surgery and radiation therapy: an analysis of 1225 patients. Cancer. 2003;97(10):2530–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11365.

Gustafson P, Dreinhofer KE, Rydholrn A. Soft tissue sarcoma should be treated at a tumor center a comparison of quality of surgery in 375 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65(1):47–50.

Scoccianti G, Innocenti M, Frenos F, et al. Re-excision after unplanned excision of soft tissue sarcomas: long-term results. Surg Oncol. 2020;34:212–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2020.04.026.

Danieli M, Barretta F, Fiore M, et al. Unplanned excision of extremity and trunk wall soft tissue sarcoma: to re-resect or not to re-resect? Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(8):4706–17. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09564-6.

Sacchetti F, Alsina AC, Morganti R, et al. Re-excision after unplanned excision of soft tissue sarcoma: a systematic review and metanalysis. The rationale of systematic re-excision. J Orthop. 2021;25:244–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2021.05.022.

Styring E, Billing V, Hartman L, et al. Simple guidelines for efficient referral of soft-tissue sarcomas: a population-based evaluation of adherence to guidelines and referral patterns. J Bone Joint Surg. 2012;94(14):1291–6. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.K.01271.

Casali P, Nazionale Tumori I, Nora Drove I, et al. The Sarcoma Policy Checklist. 2017.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (Great Britain). Improving Outcomes for People with Sarcoma: The Manual. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2006.

Liang Y, Guo TH, Xu BS, et al. The impact of unplanned excision on the outcomes of patients with soft tissue sarcoma of the trunk and extremity: a propensity score matching analysis. Front Oncol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.617590.

Blay JY, Honoré C, Stoeckle E, et al. Surgery in reference centers improves survival of sarcoma patients: a nationwide study. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1143–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz124.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Jenna Mendoza-Gonzales, our sarcoma nurse coordinator and research coordinator for her contributions to this project and to the care of our patients. This work was supported by the National Academy of Science & Technology Philippines and the University of the Philippines College of Medicine (Grant Number: RGAO 2020-0069).

Funding

This work was supported by a research fellowship grant from the National Academy of Science and Technology Philippines and a faculty research grant from the University of the Philippines College of Medicine (Grant Number: RGAO 2020-0069). The funding sources were not involved in the study design, conduct of the research, writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Gracieux Fernando—Honoraria, RTD Speaker: Roche Philippines; Honoraria, Conference Speaker, RTD Speaker: Novartis Philippines; Honoraria, Webinar Moderator; RTD Speaker: Boehringer Ingelheim; Honoraria, Conference Speaker: GSK Philippines; Honoraria, Conference Speaker: Beacon Bangladesh; Honoraria, Conference Speaker; RTD Speaker: Roche Malaysia; Honoraria, Conference Speaker: Roche Myanmar.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, E.H.M., Araneta, K.T.S., Gaston, C.L.L. et al. Unplanned Excision of Soft Tissue Sarcomas of the Extremities in a Low-to-Middle-Income Country. Ann Surg Oncol 30, 3681–3689 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13188-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-023-13188-x