Abstract

Background

Autism is not a discreet condition and those families members with autistic propend are more likely to display autistic symptoms with a wide range of severity, even below the threshold for diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Even with a parental history of schizophrenia, the likelihood of autistic spectrum disorder was found to be 3-fold greater. The aim of this study is to assess autistic traits among offspring of schizophrenic patients in the age group from 4 to 11 years and compare it in the offspring of normal individuals, and its association with the sociodemographic data. To determine whether schizophrenic parents are a risk factor to autistic traits in their children.

Results

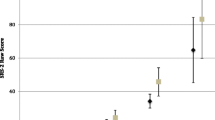

There was a statistically significant (P < 0.05*) increase in Autism Quotient Child scores of the case group where 47.2% had a score equal or more than the cutoff point (76), while only 17 19.4% of the control group had the same score with odds = 3.71 indicating that children of schizophrenic parents 18 were three times likely to have Autism Quotient-Child score greater than or equal to the cutoff point (76) than 19 children of healthy parents. No statistically significant association (P ≥ 0.05) was found between all 20 sociodemographic characteristics and Autism Quotient-Child scores among the case group except for family 21 income and social class where there was a statistically significant association (P < 0.05) between insufficient income 22 and low social class and higher Autism Quotient-Child score (≥ 76).

Conclusions

Children of schizophrenic parents are at high risk to have autistic traits than children of normal parents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are demonstrated by three features: [3] difficulties with social interaction, difficulties with social communication, and the presence of restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. Research supports the role of autism at or near the extreme end of a spectrum of autistic characteristics, particularly concerning social and communicative behavior deficits found in the general population [15, 16].

In addition, DSM-5 does not explain the wider range of sub-threshold symptoms dispersed in non-clinical persons and the occurrence of autistic-like symptoms in clinical patients with other psychiatric conditions [21, 22]. Studies among unaffected first-degree relatives of ASD patients firstly identified, the sub-threshold “Autistic Traits” (ATs) (mild in severity and the same clinical manifestations of ASD) [8, 35]. They were also found to be spread among the general population and high-risk groups [20, 51].

In the general population, sub-threshold ATs are distributed; their presentation can differ based on their quantity and quality as well as environmental interaction; ASD phenotypes are the tip of the iceberg of many potential psychiatric expressions within full-threshold manifestations (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, borderline personality underlying the autism spectrum). This fact is well expressed in the prevalence of ASD comorbidities and the high prevalence of ATs in clinical cases [4, 22].

Knowing ATs and their neurobiology can be the basis for atypical behaviors associated with independent thinking and originality, as well as subjective feelings of individuality and others. These personality traits constitute both a possible life event vulnerability factor and a potential hyper-adaptive element for particular areas of interest and activities. ATs may describe the cognitive restructuring and problem-solving processes of those individuals who do not share their group’s vision but are a mixture of special skills and weaknesses [20, 25].

On the other hand, the tangled connection between autism spectrum, stressful events, and mood symptoms may be of explicit interest in explaining the role of life events in impacting on the illness psychopathology [12, 19, 23].

With numerous genetic and environmental factors affecting disease risk, autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia have complex inheritance patterns. In the etiology of both conditions, ample evidence has shown that genetic factors play a role. While clinically distinct disorders are ASD and schizophrenia, available evidence indicates that genetic overlap is present. In the general population, these conditions occur at a higher rate than predicted [14].

Schizophrenia in parents is a substantial risk factor for ASD in siblings, and exposure to schizophrenia in siblings is also a major risk factor for ASD. In other words, with history of schizophrenia in the parents, the risk of ASD was 2.9 times greater in both the Stockholm County cohort and the Swedish national cohort [53].

Therefore, we aimed to determine whether schizophrenia in the parents is a risk factor of autistic traits in their children in comparison with normal individuals using the Autism Spectrum Quotient-Children’s version (AQ-Child) questionnaire and its association with the sociodemographic data.

Methods

Study design and setting

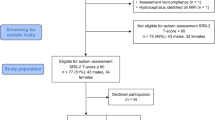

A case-control study was performed from May 2020 to October 2020 in the Psychiatric Department of Zagazig University Hospitals, Zagazig City, Sharkia Governorate, Egypt. The sample was selected randomly from the offspring of schizophrenic patients attending the outpatient clinic or admitted to the psychiatric department (cases group) and from offspring of the normal populations (control group). All participants were screened according to the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine eligibility for participation in the research.

The sample size was calculated by open Epi according to the following: percent of autistic symptoms among the normal population was 2.7% [41] and among schizophrenic parents was 55.6% [49] so at the power of study 99% and CI 99%, the sample size was calculated to be 72 (36 cases and 36 controls).

Inclusion criteria

Cases are offspring of schizophrenic patients in the outpatient clinic or admitted to the psychiatric department, of both sexes, from 4 to 11 years of age, who had only one parent with schizophrenia. Controls are children of normal parents from the general population, aged from 4 to 11 years.

Exclusion criteria

Offspring out of the determined age group, with psychiatric disorders or intellectual disabilities, with any organic disorder affecting mentality, or whose both parents were schizophrenic, were excluded.

Methods

The healthy spouse was asked to fill a semi-structured questionnaire designed to collect the following: sociodemographic data of the child and his or her family (child’s name, age, gender, residence, education, social status, age of the parents, the occupation of the parents, and their education); medical, neurological, and psychiatric history; history of schizophrenia in one of the parents of the child (duration of the disorder, compliance on treatment, and the subtype of the schizophrenia). Schizophrenia was diagnosed according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria. To rule out any neurological and metabolic conditions and brain injuries, physical and neurological examinations were performed.

Before applying the AQ-Child questionnaire on the children of the schizophrenic parents, mental retardation was excluded by applying the Stanford-Binet Intelligence scale, fifth edition [44].

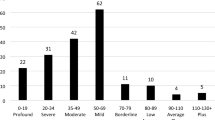

The AQ-Child is a 50-item questionnaire reported by the parents; it was developed to find out the autistic traits in children, aged 4 to 11 years. Items were formulated to produce a nearly equivalent agree/disagree response to avert bias in response. It is formed of a series of descriptive statements intended to test five areas of functioning related to autism and the wider phenotype: social abilities (items 1, 11, 13, 15, 22, 36, 44, 45, 47, and 48), attention switching (items 2, 4, 10, 16, 25, 32, 34, 37, 43, and 46), imagination (items 3, 8, 14, 20, 21, 24, 40, 41, 42, and 50), details attention (items 5, 6, 9, 12, 19, 23, 28, 29, 30, and 49), and communication (items 7, 17, 18, 26, 27, 31, 33, 35, 38, and 39); each of these functions is represented by ten questions. High scoring is compatible with more “autistic-like” behavior [5].

Items are rated as 1 for an answer in the “autistic” direction and 0 for a “non-autistic” response in the scoring system of Baron-Cohen et al. [7]. In our research, the response scale depended on the scoring scheme utilized in the most recent AQ-Adult studies [27], in which the response scale is considered a four-point Likert scale. Parents rated the extent to which they agree or not agree with the children’s information in the following response categories: definitely agree represented by 0, slightly agree represented by 1, slightly disagree represented by 2, and disagree represented by 3. As required, these items were reversely scored. This technique was used when it was thought that additional data was used in the extent of endorsement of each item and was thus maintained. Total AQ scores were represented by the summation of each item score. By summation of each item score, total AQ scores were represented as 0 for minimum AQ score that indicates the absence of autistic traits and 150 for maximum score that indicates the full presence of all autistic items [5].

Both high sensitivity (95%) and high specificity (95%) presented by a score of 76. With the cutoff of 76, control girls was fewer than 2% and 7% of control boys scored at or over the autism spectrum conditions (ASC) cutoff, while 95% of children with Asperger syndrome (AS)/high-functioning autism (HFA) and 95% of autistic children scored at or over this cutoff [5]. When using some cutoff to indicate diagnosis, caution should be used because the diagnosis does not depend on an absolute score but on impairments that the traits contribute to in their everyday functioning [2].

If the resulting AQ score was at or above 76, then follow-up with a medical practitioner (psychiatrist) is needed to perform further tests to confirm the diagnosis of ASD or Asperger’s syndrome [54].

In this research, a qualified translation center translated the AQ-Child to Arabic (CITA: Italian Center for Translation). Thereafter, another qualified professional center retranslated it into English, and a comparison was made between this English version and the original (English) AQ-Child’s version. Cronbach’s α coefficients were estimated and it was high (α = 0.8). The AQ-Child Arabic version was validated by three professors of psychiatry (face validity). After that, the total score of the Arabic version of the AQ-Child was compared with each part of it to test the internal consistency.

Statistical analysis

The mean, standard deviation (SD), and range are being analyzed by SPSS software (ver. 20). The nominal variables are being represented in the form of percentages and frequencies. The t-test and chi-square are being used for quantitative and qualitative data, respectively. Correlation coefficient test (r) was used to correlate the illness duration of schizophrenic parents and Autism Quotient (AQ)-Child score.

Results

A total of 72 children were included in this research who are divided into two groups: a case group composed of 36 children with only one schizophrenic parent and a control group composed of 36 children with healthy parents. Sociodemographic data of both groups showed that there was no statistical significant difference (P ≥ 0.05) between them, confirming they are matched. The highest proportion of case group had child age > 7–11 years (77.8%), male child sex (55.6%), primary child education (69.5%), fathers’ age 40–59 years (58.3%), mothers’ age 40–59 years (50%), uneducated fathers (72.2%), uneducated mothers (63.9%), working fathers (58.3%), not working mothers (91.7%), insufficient family income (66.7%), and low social class (77.8%); also, the highest proportion of the control group had similar distribution as follow: 86.1%, 52.8%, 80.6%, 52.8%, 50%, 52.8%, 58.3%, 61.1%, 80.6%, 52.8%, and 88.9%, respectively (Table 1).

Regarding clinical characteristics of schizophrenic parents, the mean illness duration was 9.03 ± 7.16 years and about two thirds of them (69.4%) had range duration of illness from 1 to 10 years. More than half of schizophrenic parents were mothers (55.6%) and 41.6% of them had a positive family history, and the majority of them had undifferentiated schizophrenic subtype, incompliant treatment, and negative consanguinity with 72.2%, 86.1%, and 83.3%, respectively (Table 2).

On comparing Autism Quotient-Child scores among the studied groups, we found there is a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05*) between the two groups (case and control) where (47.2%) of the case group had score equal or more than the cutoff point (76) and only (19.4%) of the control group had the same score with odds = 3.71 indicating that children of schizophrenic parents were nearly four times (OR = 3.71) more likely to have autistic traits than children of healthy parents (Table 3).

Among the case group, there is a significant association (P < 0.05) between family insufficient income and low social class and higher incidence of autistic traits (AQ-Child score ≥ 76). Besides, the highest proportion of older age children (7–11 years), preparatory education, older age fathers (≥ 60 years), older age mothers (o 60 years), uneducated fathers, uneducated mothers, non-working fathers, and non-working mothers associated with higher AQ-Child score (≥ 76) but with no statistically significant value (Table 4).

On assessing the relationship between clinical characteristics of schizophrenic parents and AQ-Child score among the case group, we detected that children of schizophrenic parents who have had a longer duration of illness, paranoid subtype, and non-compliant treatment, with positive consanguinity, and positive family history that had more autistic traits (AQ-Child score ≥ 76) but with no statistical significance (P ≥ 0.05) (Table 5).

Finally, Table 6, revealed no significant association (P ≥ 0.05) between all sociodemographic characteristics and AQ-Child score among the control group. Finally, there is week positive correlation between duration of illness of schizophrenic parents and Autism Quotient Child scores (Table 7).

Discussion

Previous studies revealed that psychiatric disorders are more common among relatives of children with ASD [9, 30, 39], whereas there are few studies that had included autistic traits in psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia. Meanwhile, our study focused on the prevalence of autistic traits among children of schizophrenic parents, comparing them with children of non-psychiatric parents, and thus our study is considered novel in Egypt.

Genetic overlap between ASD and schizophrenia has been proved by recent studies [26], where both of them are highly heritable disorders, with schizophrenia having a 25–33% genetic contribution and ASD having a 49% genetic contribution. Both disorders have hereditary influences that lead to impaired social contact, but their genetic associations have distinct developmental profiles that relate to their clinical onset and symptoms [52].

Furthermore, new research indicates that changes in gene expression regulation, synaptic architecture and function, and immunity are all important cellular mechanisms in both conditions [34]. Besides that, growing evidence indicates that complex gene-environment interactions play a role in both disorders [11].

In the current study, we found that the prevalence of autistic traits among the children of schizophrenic parents is 47.2%, who scored above the cutoff point on the AQ-Child Questionnaire and 19.4% of children of healthy parents.

In agreement with our study, studies revealed that the presence of schizophrenia in the parents or other mental disorder increases the risk of autistic traits or autism in their children; Salah El-Deen and Mahdy [49] found that the prevalence of autistic traits among the children of schizophrenic patients is 44.4% who scored above the cutoff point on AQ-Child Questionnaire. Also, Sullivan et al. [53] found in a Swedish and a Stockholm County cohort study that the presence of schizophrenia in parents was accompanied by an increased risk for ASD; it was approximately three times higher in those whose parents suffered from schizophrenia. Moreover, Larsson et al. [33] studied the relationship between the psychiatric history of the parents, and the autism risk in their children and detected a markedly increased risk for autism in the offspring of parents with a psychiatric history of schizophrenia or mood disorder.

Other studies asserted that ASD children are a risk factor to their parents to have schizophrenia or other mental disorder; schizophrenia spectrum disorders are more common among parents who have an autistic child [31]. Also, Daniels et al. [18] stated that parents of autistic children were more borne to be hospitalized for a mental disorder than parents of control children. Schizophrenia among both the mothers and the fathers was associated with autism in their children with odds ratio 1.9 and 2.1, respectively. There are common genetic factors shared between ASD and schizophrenia [10, 13].

This is consistent with the results of the current study where the presence of schizophrenia in either mother or the father increases the autism risk in the offspring. First, regarding the impact of schizophrenia in the parents on the ASD outcome, it is clear from this study that the presence of schizophrenia in the mother or the father increases the autism risk in the offspring and this is positively correlated with the result of our study. Second, this study showed that schizophrenia in both mothers and fathers increased the ASD risk in the offspring.

In contrast, Posserud et al. [41] confirmed that the frequency of children with high scores above the cutoff point on the Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ) was about 2.7% in the general population of children aged 7–9 years, and this difference may be due to the use of a different questionnaire. Another possible cause for our findings is that we used a self-report questionnaire, such as the AQ, which may not be reliable in clinical assessments, also it may be attributed to that in the last few years, the overuse of electronic games, videogames, and another modern way of technology, which lead to symptoms like autistic traits (prefer to be alone, have weak social skills, have problems in co** easily in social situations, are not eager to communicate and speak in public).

Regarding sex

In this study, there was no statistically significant relationship between the prevalence of autistic traits and the sex of children in both groups.

In agreement with our results, two studies included their participants who are children with one schizophrenic parent; one of them found that the risk of ASD outcome was not correlated to the sex of the child [33] and the other one reported that there was no statistical significant association between gender of the children of schizophrenic patients and their AQ scores [49].

Other studies carried on autistic children of non-psychiatric parents found that there was no correlation between the severity of autistic symptoms and the sex of children [28, 40]. Some found that there were no gender differences in autistic symptoms but the daily living skills functioning was better in females [37].

In contrast with our study, Allison et al. [1] stated that there was a significant difference as regard sex, by higher scoring of boys than girls on the quantitative version of the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (Q-CHAT). This finding proposed that boys may exhibit more difficulties in social communication and rigid repetitive behaviors than girls in the stage of early development.

Ruzich et al. [47] also found a mild impact of sex on AQ in their study, with males scoring an average of 2.5 points higher than females.

In another study measuring autistic characteristics in the general population, it was observed that males had higher AQ scores than females [48]. The previous results are inconsistent with our study but may be due to our small sample size and methodological differences, in addition to the absence of a family history of psychiatric disorders in the selected probands.

Russell et al. [45] found a clear gender bias as regards autistic features with boys having a greater proportion of autistic features than girls, whether or not diagnosed. Rutter [46] stated that boys have ASD four times more than girls. Holtmann et al. [28] also revealed significant gender difference but this time there is more symptoms in females than males, particularly social problems, attention problems, and thought problems.

Regarding the age of parents

This study found no significant relationship between the severity of autistic traits in children and the age of parents in both case and control groups.

In agreement with our study, Salah El-Deen and Mahdy [49] reported that there was no statistical difference in age of schizophrenic parents and risk of autistic traits in their offspring. Other studies carried on children of ono-psychiatric parents also found no significant association between the age of the parents and risk of autism [29, 33].

In contrast to our study, many studies confirmed the strong correlation between the increased risk of having ASD in the children and the age of the parent [24, 38] or the age of mothers [50] or the increase in the order of the childbirth.

Reichenberg et al. [43] asserted that the risk of ASD increases about 6 times in offspring of men 40 years or older when they are compared with those of men younger than 30 years. Also, another study stated that every 10 years increase in the age of mothers or fathers increases the risk of ASDs in their children (1.3 and 1.28 folds, respectively) [17].

The discrepancy with our results may be because of the small sample size and methodological difference; also, we studied autistic traits not autism on offspring of schizophrenia parents.

Regarding socioeconomic status

In our study, there was no significant statistical difference regarding the relationship between the severity of autistic traits in the children and the socioeconomic status of the schizophrenic parent except in insufficient income and low social class were more associated with AQ-Child score; also, there was no statistical association between socioeconomic status and AQ-Child score among the control group.

In agreement with our study, Kelly et al. [32] found that income status of mothers had a strong association with the likelihood of a child having a diagnosis of autism in their primary care records. Ayoub et al. [6] also mentioned in their study results that the prevalence of ASD with associated intellectual disability (ID) was higher in areas with the highest level of deprivation and the highest percentage of unemployed adults, single-parent families, and persons with no diploma. Rai et al. [42] in their study mentioned that lower socioeconomic status was associated with an increased risk of ASD. Also, Malhotra et al. [36] found a significant association between autism and families coming from the upper socioeconomic status. That was contributed to the availability of health care services for those families.

In contrast, some studies stated that no statistically significant association between the risk of autism and socioeconomic status [6, 33]. Others found that maternal socioeconomic class did not significantly associate with having an ASD diagnosis nor displaying severe autistic traits [45].

The inconsistency of these results to ours may be due to these studies not comparing between healthy and schizophrenic parents as in our study; also, the difference may be due to the parents in our case group having a serious mental illness unlike parents of those studies who did not suffer from any mental illness.

Regarding education and occupation of the parents

In this study, there was no significant statistical difference regarding the relationship between the severity of autistic traits in the children and the education and the occupation of their parents in the case and control group.

In agreement with our study, Salah El-Deen and Mahdy [49] reported that there was no statistical difference relation between the severity of autistic traits in the children and the education and the occupation of schizophrenic parents. Other studies that carried on ASD children of non-psychiatric parents revealed that the risk of ASD was not associated with education or occupation of the parents [6, 42] or maternal education [33].

On the other hand, Rai et al. [42] mentioned in their study that children of parents with manual occupations were at higher risk of ASD. This is inconsistent with the results of our study maybe because of the cultural differences and this study was applied in Sweden, a country that has routine screening for developmental problems, free universal healthcare, and thorough protocols for diagnoses of autism.

Regarding correlation of illness duration of schizophrenic parents and autism quotient (AQ) scores of their offspring

In this study, there is a weak positive correlation between duration of illness of schizophrenic parents and AQ meaning AQ scores will increase when the duration of schizophrenia illness increase but this correlation is with no statistical significance (Table 7). This non-significance may be due to the small sample size of our study this point can be overcome in the future research. Unfortunately, we did not find any study that approached this point of correlation.

Conclusions

Our study provides that there was a significant increase in the prevalence and severity of autistic traits among children of schizophrenic parents when we compared them with the children of normal parents. There is a significant association between low family income and low social class and higher incidence of autistic traits, but not with other sociodemographic data and clinical characteristics of schizophrenic parents. No significant association was found between sociodemographic characteristics among the control group and autistic traits.

Limitations

-

1.

The small sample size in the case and control groups

-

2.

The data taken through the Autism Spectrum Quotient Questionnaire were obtained from the parents, but no additional reports could be obtained by teachers.

-

3.

More than three fourths of the participants are of low socioeconomic status, and the rest are of moderate level, as they are the patients’ follow-up in university hospitals.

Recommendation

-

1.

Increasing the sample size for better relationships

-

2.

Follow-up of these children especially those with a high score, and apply the diagnostic tools of ASD

-

3.

The sample of the participants should involve all socioeconomic levels for better findings

-

4.

Moreover, screening for psychiatric comorbidities that may be associated with severe autistic traits is recommended.

-

5.

More studies focused on autistic traits should be done for early detection and proper approach and putting them in a suitable program for the best quality of life.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AQ:

-

Autism quotient

- AQ-Child:

-

Autism Spectrum Quotient-Children’s version

- ASC:

-

Autism spectrum condition

- ASDs:

-

Autistic spectrum disorders

- AS:

-

Asperger syndrome

- ASSQ:

-

Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire

- ATs:

-

Autistic traits

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CITA:

-

Italian Center for Translation

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5

- DSM-IV-TR:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4e) text revision

- HFA:

-

High function autism

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ID:

-

Intellectual disability

- Q-CHAT:

-

Quantitative version of Checklist for Autism in Toddlers

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- χ 2 :

-

Chi-square test

- *:

-

statistically significant

References

Allison C, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Charman T, Richler J, Pasco G, Brayne C (2008) The Q-CHAT (Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers) a normally distributed quantitative measure of autistic traits at 18–24 months of age: a preliminary report. J Autism Dev Disord 38(14):14–1425

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC

American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890423349

Anckarsäter H, Stahlberg O, Larson T et al (2006) The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament, character, and personality development. Am J Psychiatry 163(7):1239–1244. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1239

Auyeung B, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Allison C (2008) The Autism-Spectrum Quotient: Children’s Version (AQ-Child). J Autism Dev Disord. 38:1230–1240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0504-z

Ayoub MD, Virginie E, Dana K et al., (2015): Socioeconomic disparities and prevalence of autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability Published: November 5.

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E (2001) The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. J Autism Dev Disord 31(1):5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653411471

Billeci L, Calderoni S, Conti E et al (2016) The Broad Autism (Endo) Phenotype: neurostructural and neurofunctional correlates in parents of individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Front Neurosci. 10:346

Bölte S, Knecht S, Poustka F (2007) A case-control study of personality style and psychopathology in parents of subjects with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 37(2):243–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0165-3

Burbach JP, Van der Zwaag B (2009) Contact in the genetics of autism and schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci 32(2):69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2008.11.002

Burrows EL, Hannan AJ (2013) Decanalization mediating gene-environment interactions in schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders with neurodevelopmental etiology. Front Behav Neurosci. 7:157

Carmassi C, Corsi M, Bertelloni CA, Carpita B, Gesi C, Pedrinelli V, Massimetti G, Peroni D, Bonuccelli A, Orsini A, Dell’Osso L (2018) Mothers and fathers of children with epilepsy: gender differences in post-traumatic stress symptoms and correlations with mood spectrum symptoms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 14:1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S158249

Carroll LS, Owen MJ (2009) Genetic overlap between autism, schizophrenia and, bipolar disorder. Genome Med 1:Article number: 102

Chisholm K, Lin A, Abu-Akel A, Wood SJ (2015) The association between autism and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a review of eight alternate models of co-occurrence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 55:173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.012

Constantino JN (2011) The quantitative nature of autistic social impairment. Pediatr Res 69(5 Pt 2):55R–62R

Constantino JN, Todd RD (2003) Autistic traits in the general population: a twin study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(5):524–530. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.524

Croen LA, Najjar DV, Fireman B, Grether JK (2007) Maternal and paternal age and risk of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 161(4):334–340. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.334

Daniels JL, Forssen U, Hultman CM, Cnattingius S, Savitz DA, Feychting M et al (2008) Parental psychiatric disorders associated with autism spectrum disorders in the offspring. Pediatrics 121:e1357–e1362

Dell’Osso L, Dalle Luche R, Carmassi CA (2015) New perspective in post-traumatic stress disorder: which role for unrecognized autism spectrum? Int J Emerg Ment Health 17:436–438

Dell’Osso L, Gesi C, Massimetti E et al (2017) Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS Spectrum): validation of a questionnaire investigating subthreshold autism spectrum. Compr Psychiatry 73:61–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.11.001

Dell’Osso L, Luche RD, Gesi C, Moroni I, Carmassi C, Maj M (2016) From Asperger’s Autistischen Psychopathen to DSM-5 Autism Spectrum Disorder and Beyond: a subthreshold autism spectrum model. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 12(1):120–131. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901612010120

Dell’Osso L, Muti D, Carpita B et al (2018) The Adult Autism Subthreshold Spectrum (AdAS) model: a neurodevelopmental approach to mental disorders. J Psychopathol 24:118–124

Dell’Osso L, Carpita B, Cremone IM et al (2019) The mediating effect of trauma and stressor-related symptoms and ruminations on the relationship between autistic traits and mood spectrum. Psychiatry Res 279:123–129

Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Newschaffer CJ, Lee L, CunniffBCM DJL, Kirby RS, Leavitt L, Miller L, Zahorodny W, Schieve LA (2008) Advanced parental age and the risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am J Epidemiol 168(11):1268–1276

Happé F, Frith U (2009) The beautiful otherness of the autistic mind. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 364(1522):1346–1350. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0009

Hoeffding LK, Trabjerg BB, Olsen L, Mazin W, Sparsø T, Vangkilde A, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Werge T (2017) Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals with the 22q11.2 deletion or duplication: a Danish nationwide, register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry 74(3):282–290. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3939

Hoekstra RA, Bartels M, Verweij CJ, Boomsma DI (2007) Heritability of autistic traits in the general population. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(4):372–377. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.4.372

Holtmann M, Bölte S, Poustka F (2007) Autism spectrum disorders: sex differences in autistic behaviour domains and coexisting psychopathology. Dev Med Child Neurol 49(5):361–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00361.x

Hultman CM, Sparén P, Cnattingius S (2002) Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology 13(4):417–423. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001648-200207000-00009

Ingersoll B, Meyer K, Becker MW (2011) Increased rates of depressed mood in mothers of children with ASD associated with the presence of the broader autism phenotype. Autism Res 4:143–148

Jokiranta E, Brown AS, Heinimaa M, Cheslack-Postava K, Suominen A, Sourander A (2013) Parental psychiatric disorders and autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res 207(3):203–211

Kelly B, Williams S, Collins S, Mushtaq F, Mon-Williams M, BWD M, Wright J (2017) The association between socioeconomic status and autism diagnosis in the United Kingdom for children aged 5–8 years of age: findings from the Born in Bradford cohort. Autism 23(2):136236131773318

Larsson HJ, Eaton WW, Madsen KM, Vestergaard M, Olesen AV, Agerbo E, Schendel D, Thorsen P, Mortensen PB (2005) Risk factors for autism: perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am J Epidemiol 161(10):916–925. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwi123

Liu X, Li Z, Fan C, Zhang D, Chen J (2017) Genetics implicate common mechanisms in autism and schizophrenia: synaptic activity and immunity. J Med Genet. 54(8):511–520. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-104487

Losh M, Adolphs R, Poe MD, Couture S, Penn D, Baranek GT, Piven J (2009) Neuropsychological profile of autism and the broad autism phenotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66(5):518–526. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.34

Malhotra S, Chakabarti S, Gupta N (2003) Pervasive developmental- disorders and its subtypes: socioeconomic and clinical profile. German J Psychiatry 6:33–39

Mandic-Maravic V, Pejovic-Milovancevic M, Mitkovic-Voncina M, Kostic M, Aleksic-Hil O, Radosavljev-Kircanski J, Mincic T, Lecic-Tosevski D (2015) Sex differences in autism spectrum disorders: does sex moderate the pathway from clinical symptoms to adaptive behavior? Sci Rep 5(1):10418. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep10418

Manzouri L, Yousefian S, Keshtkari A, Hashemi N (2019) Advanced parental age and risk of positive autism spectrum disorders screening. Int J Prev Med 10(1):135. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_25_19

Mouridsen SE, Rich B, Isager T, Nedergaard NJ (2007) Psychiatric disorders in the parents of individuals with infantile autism: a case-control study. Psychopathology 40(3):166–171. https://doi.org/10.1159/000100006

Pilowsky T, Yirmiya N, Shulman C, Dover R (1998) The Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale: differences between diagnostic systems and comparison between genders. J Autism Dev Disord 28(2):143–151

Posserud MB, Lundervold AJ, Gillberg C (2006) Autistic features in a total population of 7-9-year-old children assessed by the ASSQ (Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire). J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(2):167–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01462.x

Rai D, Lewis G, Lundberg M, Araya R, Svensson A, Dalman C, Carpenter P, Magnusson C (2012) Parental socioeconomic status and risk of offspring autism spectrum disorders in a Swedish population-based study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(5):467–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.012

Reichenberg A, Gross R, Weiser M, Bresnahan M, Silverman J, Harlap S, Rabinowitz J, Shulman C, Malaspina D, Lubin G, Knobler HY, Davidson M, Susser E (2006) Advancing paternal age and autism. Archpsyc. 63(9):1026–1032

Roid GH (2003) Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th edn. Riverside Publishing, Rolling, Meadow

Russell G, Steer C, Golding J (2011) Social and demographic factors that influence the diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46(12):1283–1293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0294-z

Rutter M (2005) Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning. Acta Paediatr 94(1):2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08035250410023124

Ruzich E, Allison C, Chakrabarti B, Smith P, Musto H, Ring H, Baron-Cohen S (2015a) Sex and STEM occupation predict autism-spectrum quotient (AQ) scores in half a million people. PLoS One 10(10):e0141229. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0141229

Ruzich E, Allison C, Smith P, Watson P, Auyeung B, Ring H, Baron-Cohen S (2015b) Measuring autistic traits in the general population: a systematic review of the autismsSpectrum quotient (AQ) in a nonclinical population sample of 6,900 typical adult males and females. Mol Autism 6(1):2. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-6-2

Salah El-Deen GM, Mahdy RS (2017) Autistic traits in offspring of schizophrenic patients. A cross-sectional study. Egypt J Psychiatry 38(3):164–171. https://doi.org/10.4103/ejpsy.ejpsy_18_17

Sandin S, Hultman CH, Kolevzon A, Gross R, MacCabe JH, Reichenberg A (2012) Advancing maternal age is associated with increasing risk for autism: a review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 51(5):477–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.02.018

Skylark WJ, Baron-Cohen S (2017) Initial evidence that non-clinical autistic traits are associated with lower income. Mol Autism 8(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0179-z

St Pourcain B et al (2017) ASD and schizophrenia show distinct developmental profiles in common genetic overlap with population-based social communication difficulties. Mol Psychiatry 00:1–8

Sullivan PF, Magnusson C, Reichenberg A, Boman M, Dalman C, Davidson M, Fruchter E, Hultman CM, Lundberg M, Långström N, Weiser M, Svensson AC, Lichtenstein P (2012) Family history of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as risk factors for autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69(11):1099–1103. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.730

Justine D (2013) Interpreting AQ test (Autism Spectrum Quotient) results. Available at: http://aspergerstest.net/interpreting-aq-test-results

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the study participants.

Funding

Nil.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SA acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation, and shared in the drafting of the article. GM designs the work and substantively revised and shared in drafting of the article. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Official permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at the Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University Hospitals (ZU-IRB#6099/31-5-2020).

Official permission was obtained from the psychiatry department at the same university.

Written informed consent was voluntarily sought from the participants, after clarifying of the aim of the study, methods, and duration of the study.

Confidentiality of data was ensured and data was only accessed by the researcher.

Study participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without giving reasons and without negatively affecting their medical care.

Consent for publication

A written informed consent was voluntarily sought from the participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amin, S.I., Salah EL-Deen, G.M. Autistic traits in offspring of schizophrenic patients in comparison to those of normal population: a case-control study. Middle East Curr Psychiatry 28, 24 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00100-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43045-021-00100-0