Abstract

The authors of the work numerically studied the aerodynamic coefficients of the sail blade, during which the patterns of three-dimensional flow around airflow and the pressure distribution field were obtained. The triangular sail blade is used as the power element of wind turbines. The sail blade modeling was based on the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations (RANS) using the ANSYS FLUENT computer program. A flow pattern is obtained, which gives a physical explanation of the nature of the airflow around the sail blade and the pressure distribution field. Comparative analyses of theory and experiment are given. In the range of Reynolds numbers from 0.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104, the change in the drag force coefficient is from 1.04 to 0.54, and the difference in the lift force coefficient is from 0.52 to 0.33.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Back in 3000 BC in Egypt, people first used wind energy in the form of sailing boats. Using the energy of the wind, the sails contributed to the boat’s movement. In 2000 BC in ancient Babylon, the first mills for grinding grain, powered by sails, appeared. Starting from the 1000s, the European crusaders, after campaigns in the Middle East, brought the concept of a Dutch-type windmill [1, 2].

In 1887, Professor James Blyth of Anderson College built the first wind turbine with sail blades in Scotland. With this significant event, a new era of develo** wind turbines with sail blades begins [3].

As a result of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which developed many fluid flow modeling techniques in the 1950s and 1960s, CFD research based on the Navier–Stokes equations began. Proof of this is the first work published by John Hess and A.M.O. Smith in 1967 on 3D flow computation [4].

In 1950–1960, research was carried out for a two-dimensional sail using numerical and experimental methods [5]. Then, in 1970, researchers experimentally investigated wind turbines with vertical and horizontal sail blades [6, 7].

Starting from the 1990s, a new era begins, the development of numerical methods for studying sails using modern computer programs. In the last two decades, numerical and experimental advances in the aerodynamics of sails have contributed to a new understanding of their behavioural patterns and improved design [8]. The authors of [9] performed a numerical simulation of a triangular sail using the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations, measuring the pressure distributions on the sails. A holistic view of the aerodynamics of leeward sails is presented in [10] using experimental and numerical studies. Data on distributed pressure and aerodynamic forces were obtained. In [11], tests were carried out to determine the aerodynamic coefficients of the sail in a wind tunnel based on a stable wind field and a simulated natural wind field. The results show that for a more accurate analysis of the aerodynamic characteristics of the sail, one cannot neglect the natural variations of the wind speed and the wind profile in the atmospheric boundary layer. Moreover, interesting numerical and experimental results were obtained on the pressure distribution on the sail at different angles [12]. The authors of [13] developed a system to study the aerodynamics of sails using real time measurements of pressure and sail shape in full size.

In [14], the authors carried out a numerical analysis of the aerodynamic characteristics of 2D winged sails and optimization of their shape and operating conditions in terms of angle of attack, flap length and deflection angle in different wind directions. Optimal design variables have been obtained that maximize the average thrust characteristics of several sail wings relative to the wind direction.

In [15], a 3D-printed rigid sail with a Reynolds number 104, was tested. It was found that on the leeward side of the sail (the suction side), the flow separates at the leading edge, again joining downstream and forming a stable vortex of the leading edge (LEV).

However, results such as the distribution of velocity and pressure vectors and the comparison of the aerodynamic coefficients of leeward sails and their inherent flow structures still need to be investigated.

Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes modelling (RANS) is the oldest approach to modelling turbulence. It involves solving a hierarchy of flow equations that introduce new apparent stresses known as Reynolds [16, 17]. In this work, the authors used the k-ε turbulence model with two equations, which provides a general description of turbulence with two transport equations for the turbulent kinetic energy k and the turbulent energy dissipation rate ε [18, 19]. Essentially, the magnitude and direction of the aerodynamic forces on the sail depend on its position relative to the airflow, which is characterised by the attack angle [20,21,22,23,24].

The aim of this work is to numerically simulate the aerodynamic coefficients of a triangular blade using software and to conduct a comparative analysis of theory and experiment.

2 Task formulation

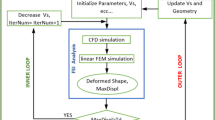

A sail mesh model with dimensions was developed for the numerical CFD. The computational analysis was carried out using the general purpose programme Fluent 14 CFD.

For the numerical modelling of a sail blade, the blade geometry was created with the following dimensions in the KOMPAS 3D programme (Table 1).

For a three-dimensional representation of the problem, the dimensions of the computational domain were taken in accordance with the dimensions of the wind tunnel.

3 Numerical simulation

3.1 Calculation grid

The computational domain is a parallelepiped with a model inside it (Fig. 1). The dimensions of the computational domain are identical to those of the working domain of the experimental wind tunnel T-1-M.

In order to determine the influence of the size of the differential grid (the number of cells) on the determination of the resistance force of the sail, calculations were carried out with the model used for three differential grids: 1 – 224,745, 2 – 500,680, 3 – 1,005,863 nodes.

Table 2 shows the drag forces obtained for low wind speeds in the range from 3 to 15 m/s. The value of C1 corresponds to the drag force received from the model used on the grid at 224,745, C2 – 500,680, and C3 – 1,005,863 nodes.

As could be seen from Table 2, the discrepancy between C2 and C3 is minimal. In further calculations we will take C2 – 500,680 because it requires relatively few energy and time resources.

To proceed to the next step, the resulting geometric model was exported to the Ansys Meshing programme. Based on this model, a finite difference model was created with a mesh of 500,680 cells. The mesh quality was checked and the boundaries of the computational domain were defined, for which the boundary conditions will apply in the future. Subsequently, the calculation grid was exported to the Fluent programme.

Modelling in Ansys Fluent is based on solving the Navier–Stokes equations, energy and continuity. For a much more practical approach, the standard k-ε turbulence model [13] is used to minimise the unknowns and present a set of equations that can be applied to a wide range of turbulent applications. The considered flow is turbulent.

The system of equations describing the gas flow is presented in the form:

Where, \(\frac{\partial V}{\partial t}\) denotes the speed change over time, \(\left(V\nabla \right)V\) denotes the component speed change, \(-\frac{1}{\rho }\nabla p\) denotes the component change pressure, \(\mathrm{\vartheta }{\nabla }^{2}V\) is the viscosity component; and \(F\) are the components characterizing the effect exerted on the liquid.

3.2 Turbulence model k-ε

The equation for turbulent kinetic energy k is written as:

Where ui are averaged components of the velocity vector in the Cartesian coordinate system, k is the kinetic energy of turbulence, \({\it{\sigma} }_{k}\) is a parameter that provides the desired dimension, \(\it E_{ij}\) is the component of the deformation rate, and \({\mu }_{t}\) is the vortex viscosity.

The equation for the dissipation of turbulent energy ε is written as:

Where, \({u}_{i}\) is the velocity component in the corresponding direction, \({E}_{ij}\) is the strain rate component, and \({\mu }_{t}\) is the eddy viscosity, \({\mu }_{t} = {\rho C}_{\mu }\frac{{k}^{2}}{\varepsilon }\).

The equations also consist of some adjustable constants \({\it\sigma }_{k}\), \({\it\sigma }_{\varepsilon }\), \({C}_{1\varepsilon }\), and \({C}_{2\varepsilon }\). The values of these constants were obtained due to numerous iterations of data fitting for a wide range of turbulent flows. They are as follows:

3.3 Boundary conditions

Sticking and non-leaking conditions are

\({\varepsilon}_{\rho}=\frac{{C}_{\mu }^{3/4}{k}_{P}^{3/2}}{{ky}_{P}}\) is Karman’s constant, where index P refers to the center of the near-wall cell of the difference grid.

Boundary conditions at the inlet are

Turbulent flow parameters are determined by setting the intensity of turbulent pulsations I of the hydraulic diameter Dhyd.

Boundary condition at the exit boundary [16] is:

4 Experimental part

4.1 Experimental model

Based on mathematical modelling and the selection of optimal geometric parameters for experimental research, a sail blade was assembled and tested. The experiments with the sail blade were carried out in the “Aerodynamic Measurements” laboratory of the “Alternative Energy” Research Centre of E.A. Buketov Karaganda University.

The experimental model of the sail is made in the form of a triangle with dimensions of 0.48 m, 0.45 m, and 0.35 m. The experiments were carried out at Reynolds numbers from 0.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104.

When studying the effect of wind on a sail, a whole set of forces arise, including aerodynamic force. The magnitude of the force, as well as the point of application of the resultant, strongly depends on the angle at which the sail (its chord) is to the wind α — this angle is called the angle of attack, as well as on the bending of the sail (Fig. 2).

Suppose we decompose the aerodynamic force into two components: parallel to X and perpendicular to the wind Y. In that case, we can estimate how much the sail will strive with the wind and move perpendicular to the wind. In this case, the Y component is called the lift (because this force causes the blade to rise when the blade is in a horizontal position), and the X component is called the drag force of the sail.

The dimensionless coefficients of drag Cx, lifting force Cy, and the following formulas determine the Reynolds number criterion:

Where, \({F}_{x}\) is the drag force, \({F}_{y}\) is the lift force, \(\rho\) is the air density, \(u\) is the flow rate, \(S\) is the midlength [midship] section area, \(l\) is the length of the lever arm, and \(L\) is the characteristic size of the sail.

The clogging coefficient is as follows:

Where, \({A}_{s}\) denotes the projected area of the sail (m2), and \({A}_{t}\) denotes the test section area of the wind tunnel (m2).

Pope and Harper (1966) [25] proposed a method for correcting the blocking effect at low wind speeds, which can be easily obtained by multiplying the input wind speed by the correction factor expressed in Eq. (12). The correction factor εt for an arbitrary shape can be determined from formula (13).

Where, \({U}_{c}\) is the adjusted wind speed (m/s), and \({\varepsilon }_{t}\) is the correction factor.

In our case, the clogging coefficient was 0.35%, which is acceptable according to the results of the work [26].

The angle of attack of the sail blade was measured by comparison with rigid control (model) instruments: angle measures and protractors.

4.2 Wind tunnel T-1-M

An experimental study of the sail blade was conducted in the T-1-M wind tunnel. According to the concept, a wind tunnel is a channel in which an artificial air flow is generated with the assistance of a fan. In this work, a wind tunnel with a closed air flow was used.

The T-1-M wind tunnel includes a working part, a diffuser, a fan, a transition channel, turning blades, leveling grids, a prechamber, and a collector (nozzle). A wind tunnel with an open test section was used in the experiments. Parameters of the working part are: diameter — 0.5 m; length — 0.8 m. The measurement error is 0.5 – 1%.

The drag and lift forces were measured with a three-component balance (Fig. 3).The flow velocity varied from 3 to 15 m/s. The velocity of the incoming airflow was measured with a Skywatch Atmos cup anemometer.

In an experimental study, a transition from a laminar flow to a turbulent one takes place in a wind tunnel. In particular, the boundary layer formed on the walls of the working part of the wind tunnel generates acoustic disturbances in the flow field, which reach the surface of the model under study and have a significant effect on the phenomenon of transition from laminar flow to turbulent one.

4.3 Measurement uncertainty analysis

In accordance with the standard [27], an analysis of the measurement uncertainty was carried out.

In our case, the measured value of the drag force and lift force is not measured directly (Y) but is determined through N other values X1, X2, X3, and XN using the functional dependence ƒ:

For each value Xi included in the model equation, it is necessary to determine the estimate xi and the standard uncertainty u(xi). Estimates of input values (x1, x2…xn) are their mathematical expectations. The standard uncertainty u(xi), associated with the estimate xi, of the measured quantity xi, is its standard deviation. In this case, each input estimate xi and the associated standard uncertainty u(xi) are obtained from the probability distribution of the input value Xi. Depending on the available information about the value of Xi, the standard uncertainty estimation methods can be type A and type B. The type A standard uncertainty estimate is obtained from a probability density function based on the observed frequency distribution. The type B standard uncertainty estimate is based on assigning a probability distribution function based on the available quantity information.

Type A standard uncertainty is calculated using the formula (15):

Where \({F}_{i}\) is the regular force measurement, \(n\) is the number of measurements, \(\overline{F }\) is the arithmetic mean, and is equal to \(\overline{F }=\frac{\sum_{n-1}^{n}{F}_{i}}{n}.\)

Using the standard uncertainty of type B, the reliability of measurements is assessed based on non-statistical information (16):

Where, \(\pm \Delta F\) are limits of permissible instrumental error, and as the force’s value, we take the force’s average value, taking into account the error of 0.5% of the three-component aerodynamic scale.

The total standard uncertainty of the measurement result simultaneously considers the influence of random and known uncertainty factors. It summarizes all uncertainty factors, considering their contribution to the measurement result. Calculated using the following formula (17):

Where, \({u}_{i}\) is the i-th uncertainty factor, \({k}_{i}\) is its weight, and \(n\) is the number of uncertainty factors.

Aerodynamic force coefficients and Reynolds number were calculated using formulas (10). The results of the analysis of the uncertainty of the coefficient of drag and lift are presented in Figs. 4 and 5, and Tables 3 and 4.

As seen from the figures, the uncertainty for both the drag force coefficient and the lift coefficient are shown as vertical bars, but they are omitted in the subsequent figures for clarity. The obtained experimental data of the drag force coefficient is approximated by a linear dependence: y = -0.2902x + 1.1411. Likewise, the experimental data of the lift force coefficient is matched by a linear dependence of the type: y = -0.0568x + 0.4771.

5 Research results

In the numerical simulation, the velocity fields and the pressure distribution in the plane of symmetry were determined for the angle of attack α = 0° at inflow velocities of 5 m/s, 10 m/s and 15 m/s.

The sail, which has a curved profile (“belly”), has the apparent wind flowing around it from two sides. The belly is one of the most important features of the sail design, affecting its quality and ability to deliver proper traction in the right direction [18]. Therefore, calculations were made to determine the fullness of the sail (pot belly), which was 10 cm.

The characteristics of the distribution of the airflow velocities are shown in Fig. 6 (a, b, c).

Figure 6 (b, c) shows that two vortex zones form behind the blade and the value of the velocities in the area in front of the sail is low; their maximum value falls on the tips of the blade. It can be seen that after flowing around the blade, the velocity decreases, the minimum flow velocity is reached behind the blade, and the maximum velocity falls on the area in front of the sail.

The characteristics of the distribution of the pressure field as it flows around the sail are shown in Fig. 7 (a, b, c). As you can see from the figures, pressure and drag increase as the speed of the airflow increases. The presence of an increased pressure in front of the sample and a vacuum behind it leads to the appearance of air resistance, which is called pressure resistance. At an inflow velocity of 15 m/s, the values of static pressure (pst = p − patm) varied from -302.6 to 186.6 Pa.

From an aerodynamic point of view, the effective angle of attack is determined to determine the ability of a sail blade to generate lift with optimal drag. In our case, the most advantageous angle of attack was α = 15°, which corresponds to the maximum aerodynamic quality of the sail blade.

Figure 8 shows the dependence of the aerodynamic quality on the angle of attack.

Aerodynamic quality is an indicator of the ratio of the lift force to the drag force at a given angle of attack: Кa = Fl/Fd.. As seen in Fig. 8, the maximum value of the lift-to-drag ratio was obtained at an angle of attack α = 15° in the experiment Кa = 0.53 and the numerical study method Кa = 0.38. Based on this, further studies of the aerodynamic coefficients of the sail blade were carried out at an angle of attack α = 15°.

Figures 9 and 10 show comparative graphs of drag and lift coefficients versus Reynolds numbers.

Figure 9 shows that an increase in the Reynolds number calculated from the flow velocity leads to a decrease in the lift force coefficient Cy of the sail blade. This is explained by the fact that the zone of high pressure is observed with an increase in Reynolds number.

Figure 10 shows a graph of a sailing blade’s drag force coefficient Cx versus the Reynolds number Re.

Graph 10 shows that the drag coefficient decreases with increasing Reynolds number, which corresponds to the physical laws of aerodynamics. These numerical and experimental studies and their comparative analysis showed satisfactory agreement.

As a result of establishing the dependences of dimensionless aerodynamic parameters on similarity criteria, in this case on the Reynolds number, universal dependencies could be used to create a real operating installation.

The obtained aerodynamic dependencies of the drag coefficient and the lift coefficient on the Reynolds number are universal, both for a small layout and for windmills of sufficiently large sizes.

The result of the numerical simulation (Fig. 9) is well approximated by the linear dependence of the reliability coefficient (R2), which explains the positive result of this calculation:

Also, according to the results of the dependence of the drag coefficient (Fig. 10), it was determined that the reliance is decreasing in nature and satisfactory agreement with the experimental data. The dependence is described by a linear dependence:

It is determined that the dependences of the aerodynamic coefficients are decreasing in nature and are in good agreement with the experimental data.

6 Conclusion

A three-dimensional model of a sailing blade has been created in the form of a triangle with dimensions of 0.48 m, 0.45 m, and 0.35 m; the experiments were carried out at Reynolds numbers from 0.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104.

A flow pattern is obtained that provides a physical explanation for the nature of the airflow around the sail blade and the pressure distribution field. It was found that zones of increased pressure form on the walls of the computational domain and at the tops of the blade, and a rarefaction zone forms behind the blade, and the greater the distance to it, the greater the increase in pressure. Two circulation zones also form behind the sail. The upper circulation zone is smaller than the lower one and its center lies much closer to the top of the blade. The disturbances from the circulation zone go beyond the integration area; as a result, the formation of reverse flows is observed.

The numerical dependences of the aerodynamic coefficients of the blade for various Reynolds numbers are established. In the range of Reynolds numbers from 0.5 × 104 to 2.5 × 104, the change in the drag force coefficient is from 1.04 to 0.54, and the difference in the lift force coefficient is from 0.52 to 0.33.

A comparative analysis of theory and experiment was carried out, which showed agreement.

The significance of this study is to increase the efficiency of using wind energy due to the optimal area of the blade, improving its aerodynamic profile and increasing the coefficient of aerodynamic thrust, reducing the initial and operating wind speed, as well as increasing the reliability of its operation. Due to the improvement of the aerodynamic characteristics of the sail and the growth of the working area of the sail blade, the wind energy utilization factor is also increased.

The patterns of changes in aerodynamic parameters obtained by the authors could help to understand the complex aerodynamic design of turbulent airflow around airfoils. Furthermore, the obtained universal dependencies of the aerodynamic coefficients could be used in engineering calculations of sail-type wind turbines with sails.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Bowen RL Jr (1960) Egypt’s earliest sailing ships. Antiquity 34(134):117–131

Stowers A (1955) Observations on the history of water power. Trans Newcomen Soc 30(1):239–256

Hardy C (2010) Renewable energy and role of Marykirk’s James Blyth, In: The courier. DC Thomson & Co Ltd, Dundee

Hess JL, Smith AMO (1967) Calculation of potential flow about arbitrary bodies. Prog Aerosp Sci 8:1–138

Feldman L (1989) XERXES: a sail bladed wind turbine. In: Proceedings of the 24th intersociety energy conversion engineering conference, Washington DC, 1989

Newman BG, Ngabo TM (1978) The design and testing of a vertical-axis wind turbine using sails. Energy Convers 18(3):141–154

Taylor DA (1986) The design and testing of a horizontal axis wind turbine with sailfoil blades. Dissertation, The Open University

Souppez JBRG, Arredondo-Galeana A, Viola IM (2019) Recent advances in downwind sail aerodynamics. Paper presented at the SNAME 23rd Chesapeake sailing yacht symposium, Annapolis, 15-16 March 2019

Viola IM, Bot P, Riotte M (2013) Upwind sail aerodynamics: A RANS numerical investigation validated with wind tunnel pressure measurements. Int J Heat Fluid Flow 39:90–101

Bayati I, Muggiasca S, Vandone A (2019) Experimental and numerical wind tunnel investigation of the aerodynamics of upwind soft sails. Ocean Eng 182:395–411

Zeng X, Zhang H (2018) Experimental study of the aerodynamics of sail in natural wind. Polish Marit Res 25(s2):17–22

Richards PJ, Lasher W (2008) Wind tunnel and CFD modelling of pressures on downwind sails. Paper presented at the BBAA VI international colloquium on bluff bodies aerodynamics & applications, Milano, 20-24 July 2008

Bergsma F, Motta D, Le Pelley D et al (2012) Investigation of shroud tension on sailing yacht aerodynamics using full-scale real-time pressure and sail shape measurements. Paper presented at the 22nd international HISWA symposium on yacht design and yacht construction, Amsterdam, 12-13 November 2012

Jo Y, Lee H, Choi S (2013) Aerodynamic design optimization of wing-sails. Paper presented at the 31st AIAA applied aerodynamics conference, San Diego, 24-27 June 2013

Arredondo-Galeana A, Viola IM (2018) The leading-edge vortex of yacht sails. Ocean Eng 159:552–562

Jones P, Korpus R (2001) International America’s cup class yacht design using viscous flow CFD. Paper presented at the SNAME 15th Chesapeake sailing yacht symposium, Annapolis, 26 January 2001

Lasher W (1999) On the application of RANS simulation for downwind sail aerodynamics. Paper presented at the SNAME 14th Chesapeake sailing yacht symposium, Annapolis, 29-30 January 1999

Launder BE, Spalding DB (1974) The numerical computation of turbulent flows. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 3(2):269–289

Kusaiynov K, Tanasheva NK, Min’kov LL et al (2016) Numerical simulation of a flow past a triangular sail-type blade of a wind generator using the ANSYS FLUENT software package. Tech Phys 61(2):299–301

Tanasheva NK, Tleubergenova AZ, Shaimerdenova KM et al (2021) Investigation of the aerodynamic forces of a triangular wind turbine blade for the low wind speeds. Eurasian Phys Tech J 18(4):59–64

Alibekova AR, Kusaiynov KK, Kambarova ZT et al (2015) Experimental tests of an experimental wind power plant in natural wind under different climatic conditions. Bull Karaganda Univ Phys Ser 78(2):44–48

Kusaiynov K, Kambarova ZT, Tanasheva NK et al (2015) Flow past the sail blade of a wind turbine. J Eng Phys Thermophys 88(2):497–503

Sakipova SE, Tanasheva NK, Kivrin VI et al (2016) Study of aerodynamic characteristics of the model of a wind turbine with rotating cylinders. Eurasian Phys Tec J 13(2):111–116

Tanasheva NK, Kunakbaev TO, Dyusembaeva AN et al (2017) Effect of a rough surface on the aerodynamic characteristics of a two-bladed wind-powered engine with cylindrical blades. Tech Phys 62(11):1631–1633

Pope A, Harper JJ (1966) Low-speed wind tunnel testing. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Al-Obaidi ASM, Madivaanan G (2022) Investigation of the blockage correction to improve the accuracy of Taylor’s low-speed wind tunnel. J Phys Conf Ser 2222:012008

International Organization for Standardization (2008) ISO/IEC Guide 98–3:2008 Uncertainty of measurement — Part 3: Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement (GUM:1995). https://www.iso.org. Accessed 24 Jan 2023

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank engineer Nurlan Botpayev from E.A. Buketov Karaganda University for his suggestion on the experimental sail blade model design.

Funding

The work was carried out with the financial support of the Science Committee of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (IRN AP14870066 “Development and creation of an energy-efficient combined vertical-axial wind power plant using a gearless low-speed electric generator”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research output comes from joint efforts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tleubergenova, A.Z., Tanasheva, N.K., Shaimerdenova, K.M. et al. Mathematical modeling of the aerodynamic coefficients of a sail blade. Adv. Aerodyn. 5, 14 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42774-023-00140-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42774-023-00140-6