Abstract

Background

To realize the clinical characteristics of long QT syndrome (LQTS) caused by antiseizure medicines (ASMs), and to improve the prevention and management of ASM-acquired QT syndrome.

Case presentation

A case of ASM-acquired QT syndrome was diagnosed and relevant literature was reviewed. The case was a 7-year-old boy who presented with a sudden onset of panic followed by changes in consciousness, with or without convulsions, lasting from tens of seconds to 3 min. The patient then received antiepileptic treatment with valproic acid, levetiracetam and oxcarbazepine and was seizure free for about a year. However, on August 12, 2021, his illness flared up again. Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed the background activity was slow, and no obvious epileptic discharge was detected. But electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a surprisingly prolonged QT interval (770 ms). Torsades de Pointes was found during Holter monitoring, while electrolyte levels were normal. The ECG recordings gradually returned to normal after stop** ASMs. For literature search, only 21 related papers were obtained after reading titles and full-texts of 105 English-language papers retrieved using keywords "acquired QT interstitial syndrome/acquired Long QT Syndrome (aLQTS)" and "anti-epileptic seizure drugs/ASMs", in the databases of Wanfang, CNKI, Pubmed, and other databases, from publication year 1965 to October 26, 2021. There are 12 types of drug-acquired LQTS caused by ASMs, most of which are Na+ blockers, but LQTS caused by oxcarbazepine had not been reported previously.

Conclusions

ASMs such as oxcarbazepine can cause acquired LQTS. When Na+ or K+ channel blockers are used clinically, ECG should be reviewed regularly and abnormal ECG should be intervened in time to reduce iatrogenic accidents in patients with epilepsy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) is a rare and often preventable cause of sudden cardiac death in young adults. Its prevalence is about 1/2500 [1]. According to the Practice Guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology, the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in children is 0.22/1000 [2], accounting for 7%-17% of the mortality of patients with epilepsy. QT prolongation has been identified as one of the main mechanisms of SUDEP, as it is associated with fatal arrhythmias. This condition may be further aggravated by antiepileptic treatment. Although the exact pathophysiological mechanism of SUDEP remains uncertain, there are growing concerns on the impairment of cardiac function, including arrhythmias caused by seizures. In addition, the potential role of antiepileptic seizure medicines (ASMs) has been proposed [3]. Although clinical data suggest that the use of most antiepileptic drugs does not cause an additional risk of QT prolongation, there is a lack of sufficient evidence that these drugs are completely risk-free for all patients [4]. At present, about 10 types of ASMs have been reported to induce acquired LQTS [5,6,7]. However, LQTS caused by oxcarbazepine has not been reported before, and there is no consensus on ASMs associated with ECG changes and an arrhythmia risk. To advance the understanding of the ASM-acquired LQTS and improve the management of this condition, we report a case of oxcarbazepine-induced LQTS, combined with a review of related literature.

Case presentation

General information

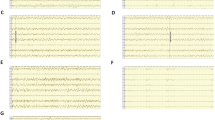

The patient was a 13-year-old boy. In November 2015 at the age of 7, he experienced the first seizure, manifested as a sudden fear-like performance without an obvious cause in the awake state, followed by systemic rigidity, accompanied by limb twitching, which lasted for about 2–3 min, and the attack relieved naturally. Then the patient was sent to the local hospital, but the specific treatment was not clear. On March 9, 2016, the patient had a similar seizure. The presentation was the same as before, sometimes accompanied by secondary generalized tonic–clonic seizures. He was diagnosed as epilepsy (focal motor seizures with impaired awareness and focal progression to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures). On March 25, 2016, valproic acid treatment was given, with the dose gradually increasing to 5 ml, q12h (24 kg, 16 mg/kg per day). On July 20, 2016, seizures still occurred, and the therapy was changed to valproic acid + levetiracetam. On May 13, 2017, seizures occurred again, with condition of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Valproic acid (same as before) + oxcarbazepine (0.075, q12h initial dose, gradually increased to 0.15, q12h) treatment was given to the patient. This therapy continued for 1 year and 3 months till August 2018, when the patient’s family refused to adjust the drug dose for the fear of side effects, but the patient still had one seizure every 5-12 months. On August 12, 2021, the clinical attack appeared again, showing sudden unconsciousness. The patient denied vomiting, chest tightness, chest pain or other symptoms before and after the attack. ECG recording in a third-level grade-A hospital in ** ASMs, a time significantly longer than the 5–7-h half-life (5–9 h in children) of the ASMs. This may be associated with valproic acid. On the 10th day, ECG showed normal activity, which indicates that the diLQTS caused by ASMs was reversible.

Conclusions

Although the diLQTS caused by ASMs is extremely rare, there is still a high clinical risk and medical risk; therefore, during the diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy, we should pay more attention to identifying LQTS and analyzing its relationship with seizures. ASMs such as oxcarbazepine can cause acquired long QT syndrome. ECG should be reviewed regularly particularly when Na+ or K+ channel blockers are used, and abnormal ECG should be intervened in time to reduce iatrogenic accidents in patients with epilepsy.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASMs:

-

Antiepileptic seizure medicines

- diLQTS:

-

Drug-induced LQTS

- LQTS:

-

Long QT Syndromes

- TdP:

-

Torsade de pointes

- VSD:

-

Voltage sensor domain

References

Lahrouchi N, Tadros R, Crotti L, Mizusawa Y, Postema PG, Beekman L, et al. Transethnic genome-wide association study provides insights in the genetic architecture and heritability of long QT syndrome. Circulation. 2020;142(4):324–38.

Abdel-Mannan O, Taylor H, Donner EJ, Sutcliffe AG. A systematic review of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) in childhood. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;90:99–106.

Christidis D, Kalogerakis D, Chan TY, Mauri D, Alexiou G, Terzoudi A. Is primidone the drug of choice for epileptic patients with QT-prolongation? a comprehensive analysis of literature. Seizure. 2006;15(1):64–6.

Feldman AE, Gidal BE. QTc prolongation by antiepileptic drugs and the risk of torsade de pointes in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;26(3):421–6.

Yager N, Wang K, Keshwani N, Torosoff M. Phenytoin as an effective treatment for polymorphic ventricular tachycardia due to QT prolongation in a patient with multiple drug intolerances. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015209521 (Published 2015).

Ciszowski K, Szpak D, Jenner B. The influence of carbamazepine plasma level on blood pressure and some ECG parameters in patients with acute intoxication. Przegl Lek. 2007;64(4–5):248–51.

Dixon R, Job S, Oliver R, Tompson D, Wright JG, Maltby K, et al. Lamotrigine does not prolong QTc in a thorough QT/QTc study in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(3):396–404.

Li CL, Liu WL, Gao YF. Current status of diagnosis and treatment of congenital and acquired long QT syndrome. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;42(5):385–91.

Barsheshet A, Dotsenko O, Goldenberg I. Genotype-specific risk stratification and management of patients with long QT syndrome. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2013;18(6):499–509.

Baracaldo-Santamaría D, Llinás-Caballero K, Corso-Ramirez JM, Restrepo CM, Dominguez-Dominguez CA, Fonseca-Mendoza DJ, et al. Genetic and molecular aspects of drug-induced QT interval prolongation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(15):8090.

Verrier RL, Pang TD, Nearing BD, Schachter SC. The epileptic heart: concept and clinical evidence. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;105: 106946.

Nishiguchi M, Shima M, Takahashi Y, Matsuoka H, Fujimoto S, Taira K, et al. A boy with occipital lobe epilepsy showing prolonged QTc in the ictal ECG. No To Hattatsu. 2002;34(6):523–7.

Medford BA, Bos JM, Ackerman MJ. Epilepsy misdiagnosed as long QT syndrome: it can go both ways. Congenit Heart Dis. 2014;9(4):E135–9.

Galtrey CM, Levee V, Arevalo J, Wren D. Long QT syndrome masquerading as epilepsy. Pract Neurol. 2019;19(1):56–61.

Zaccara G, Lattanzi S. Comorbidity between epilepsy and cardiac arrhythmias: implication for treatment. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;97:304–12.

Wilton NC, Hantler CB. Congenital long QT syndrome: changes in QT interval during anesthesia with thiopental, vecuronium, fentanyl, and isoflurane. Anesth Analg. 1987;66(4):357–60.

Uçar HK, Arhan E, Serdaroğlu A, Aydın K, Kazancıoğlu A, Akkuzu E, et al. First description of QTc prolongation associated with clonazepam overdose in a pediatric patient. Am J Ther. 2018;25(5):e558–61.

Crockford D. Re: lorazepam-induced prolongation of the QT interval in a patient with schizoaffective disorder and complete AV block. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(3):184–5.

Rojano Martín B, Maroto Rubio M, Bilbao Ornazabal N, Martín-Sánchez FJ. Elderly patient with acquired long QT syndrome secondary to levetiracetam. Neurologia. 2011;26(2):123–5.

Kwon S, Lee S, Hyun M, Choe BH, Kim Y, Park W, et al. The potential for QT prolongation by antiepileptic drugs in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;30(2):99–101.

Auerbach DS, Biton Y, Polonsky B, McNitt S, Gross RA, Dirksen RT, et al. Risk of cardiac events in Long QT syndrome patients when taking antiseizure medications. Transl Res. 2018;191:81-92.e7.

Guo JH. Interpretation of prevention and treatment suggestions for acquired long QT interval syndrome. Chin J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;39(4):289–92.

Antunes NJ, van Dijkman SC, Lanchote VL, Wichert-Ana L, Coelho EB, Alexandre Junior V, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of oxcarbazepine and its metabolite 10-hydroxycarbazepine in healthy subjects. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2017;109S:S116–23.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the patient and his family for their support and understanding of the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY was responsible for data sorting and document compilation, Professor JZ was responsible for guiding and revising the literature, HC revised the paper, and other authors were responsible for data collection. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This case report complied with the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Jiangxi Children's Hospital (JXSETYY-YXKY-20220064). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s guardian.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the legal guardian of the child, and the informed consent for publication form was signed.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Zha, J., Yi, Z. et al. Case report of antiseizure medicine-induced long QT syndrome and a literature review. Acta Epileptologica 4, 39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42494-022-00102-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42494-022-00102-3