Abstract

Background

Prophylactic administration of antipyretics at the time of immunization seems to decrease some side effects, however reduced immune responses have been reported in some studies. This systematic review aimed to investigate the effect of prophylactic use of antipyretics on the immune response following administration of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs).

Methods

A systematic review of randomized controlled trials and observational studies concerning the immune response to PCVs after antipyretic administration was performed up to November 2020 in the electronic databases of Pubmed and Scopus.

Results

Of the 3956 citations retrieved, a total of 5 randomized control trials including 2775 children were included in the review. Included studies were referred to PCV10 (3 studies), PCV7 and PCV13 (one study each). The prophylactic administration of paracetamol decreased the immune response to certain pneumococcal serotypes in all included studies. The effect was more evident following primary vaccination and with immediate administration of paracetamol. Despite the reductions in antibody geometric mean concentrations, a robust memory response was observed following the booster dose. Besides, antibody titers remained above protective levels in 88–100% of participants. The use of ibuprofen, that was evaluated in two studies, did not seem to affect the immunogenicity of PCVs .

Conclusion

Although the reviewed studies had significant heterogeneity in design, paracetamol administration seems to affect the immune response for certain serotypes. The clinical significance of reduced immunogenicity especially before booster dose needs further investigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially in children under 5 years of age, and it was estimated to cause about 294,000 deaths in children aged 1–59 months in 2015 [1, 2]. Pneumococcus is capable of colonizing the nasopharyngeal region; carriage can last from weeks to years [3]. Although colonization with pneumococcal strains is asymptomatic, it can lead to respiratory and systemic disease and is a source of spread within the community [3]. Young children are considered the most important vector for the dissemination of pneumococci within the community because of their high frequency of nasopharyngeal carriage [3].

Pneumococcal conjugated vaccines (PCVs) were licensed in 2000 and their use has a substantial impact on the burden of pneumococcal disease leading to a significant reduction in invasive pneumococcal disease through direct and indirect protection [4,5,6]. Different amounts of pneumococcal antibodies are required to protect against systemic disease and colonization, with higher titers needed for protection against certain serotypes and mucosal colonization [7,8,9].

While the contribution of pneumococcal vaccines to public health is indisputable, their administration is associated with mild adverse events such as decreased appetite, irritability, or local reactions (swelling and pain) in almost half of the recipients [10]. The incidence of some events like febrile seizures seems to occur more frequently when PCVs are co-administered with other routine vaccines [11]. There are concerns, also, that the reactogenicity of PCVs may increase by the insertion of more serotypes in the new conjugated vaccine formulations, created to deal with the “serotype replacement” phenomenon [12,13,14].

Although the adverse events of PCVs are mild and transient, they decrease parents’ acceptance and trust [15, 16]. Antipyretic analgesics are widely used to ameliorate vaccine adverse reactions and decrease parental anxiety, but their use has been associated with blunted vaccine immune responses to specific pneumococcal serotypes [17]. As two new PCVs (15-valent and 20-valent) are currently in phase 3 clinical trials, the effect of antipyretics on the antibody titer to specific serotypes will be crucial [18].

The objective of the present study is to systematically review the existing literature on the effect of prophylactic administration of antipyretics on the immune response of PCVs and provide a recommendation on the use of prophylactic antipyretics around the time of pneumococcal immunization.

Materials and methods

Literature search and study selection

In accordance with PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic review to identify the impact of antipyretic use on the immune response of pneumococcal vaccination [19]. We searched the PUBMED and SCOPUS databases for English-language publications indexed through 1 November 2020. The search strategy was based on the utilization of two major groups of keywords: Paracetamol, Acetaminophen, Ibuprofen, Fever, prophylaxis, Antipyretic (Group 1) and Immune response, Antibody response, Immunity, Immunogenicity, Immunization, Immunization, Vaccination, Vaccine (Group 2). These two categories were combined by the Boolean ‘AND’ and the terms utilized within these search categories were combined by the Boolean ‘OR’. The Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) database was used for the identification of synonyms. After compilation of articles from the database and duplicate deletion, the titles and abstracts of articles were manually screened for topic relevance. A full-text review of the articles and their reference lists were then checked by two investigators. Any discordance was resolved through discussion. The reference lists of all relevant articles originally selected for inclusion in the review and relevant reviews were also searched manually to identify potentially relevant articles that were not identified by the original electronic search.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies in English that evaluated the effect of prophylactic administration of antipyretics (paracetamol and ibuprofen) on the immunogenicity of PCVs (any type) in healthy infants/children ≥2 months by measuring serum anti-pneumococcal IgG concentrations (Geometric mean concentration-GMC) or serotype-specific opsonophagocytic activity (OPA)- Geometric mean titers (GMTs), were selected for inclusion in the present review. Randomized control studies and observational studies were eligible for inclusion as opposed to review papers, clinical guidelines, case reports, and case series. Studies concerning children with comorbidities (immunodeficiency, chronic disorders, chronic use of analgesics, or other medications) or adults were excluded. Moreover, studies where therapeutic use of antipyretics occurred were also excluded.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed for this review to collect general information (authors, setting, publication year, design), participants’ baseline characteristics (number of participants, age, vaccine type and manufacturer, vaccine dosing schedule, time between receipt of vaccine and antibody testing, GMT point estimates), intervention elements (kind of antipyretic, administration schedule-time of administration) and record all significant findings.

Methodological quality assessment

Quality assessment of studies was undertaken using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program Tool for cohort and randomized controlled trials studies (CASP) (Table 1) [20].

Results

Search results

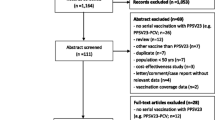

The literature search generated a total of 3956 studies, of which 186 were duplicates. Further, 3728 studies were removed due to the irrelevance of the title and abstract to the topic of the review. A full-text review of the remaining 42 studies led to the exclusion of 37, and the identification of 5 studies which fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Details of the literature search strategy are shown in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the selected studies

Five studies were designed to evaluate the impact of the prophylactic use of antipyretics on the immunogenicity of pneumococcal vaccines in children [17, 21,22,23,24] (Table 2). All studies were randomized control trials (RCT), non-blinded and were performed in European Countries: three in Czech Republic, one in Poland, and one in Romania in the 2009–2017 period.

Included studies had a total of 2775 participants. In four studies, the study population was 2–3 months of age at the time of enrollment and 12–15 months at the time of boosting [21, Although the use of antipyretics, especially paracetamol, at the time of vaccination appears to reduce the side effects of vaccines, there is a decrease in antibody titers for some PCV antigens. This may raise doubts about the practice of antipyretic administration around vaccination time. This effect differs depending on the antipyretic agent used and may have a time-dependent administration component. The clinical significance of these findings is questionable, especially between primary and booster doses where antibody titers wane. However, after the booster doses, most participants developed protective antibody titers against vaccine antigens. The small number of studies included in the above review does not allow us to draw certain conclusions. Especially after the near future possible introduction of 15 and 20-valent PCVs, questions regarding the effect of antipyretics on the immunogenicity of vaccines concerning the dose, frequency, and timing should be clarified. More well-designed future studies need to be conducted to provide clear evidence regarding the underlying mechanism and the possible association of immunogenicity with the type of antipyretics and the time of administration.Conclusions

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- PCV:

-

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccination

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- GMC:

-

Geometric mean concentration

- OPA:

-

Serotype-specific opsonophagocytic activity

- AAP:

-

American Academy of Pediatrics

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ACIP:

-

American Committee on Immunization Practices

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trials

References

Oligbu G, Fry NK, Ladhani SN. The pneumococcus and its critical role in public health. Methods Mol Biol. 1968;2019:205–13.

Wahl B, O'Brien KL, Greenbaum A, Majumder A, Liu L, Chu Y, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e744–e57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X.

Bogaert D, de Groot R, Hermans PWM. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4(3):144–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7.

Berman-Rosa M, O'Donnell S, Barker M, Quach C. Efficacy and effectiveness of the PCV-10 and PCV-13 vaccines against invasive pneumococcal disease. Pediatrics. 2020;145(4):e20190377. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0377.

Moore MR, Link-Gelles R, Schaffner W, Lynfield R, Lexau C, Bennett NM, et al. Effect of use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children on invasive pneumococcal disease in children and adults in the USA: analysis of multisite, population-based surveillance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(3):301–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71081-3.

Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Schuck-Paim C, Lustig R, Haber M, Klugman KP. Effect of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on admissions to hospital 2 years after its introduction in the USA: a time series analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):387–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70032-3.

Lau WC, Murray M, El-Turki A, Saxena S, Ladhani S, Long P, et al. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on childhood otitis media in the United Kingdom. Vaccine. 2015;33(39):5072–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.08.022.

Trotter CL, McVernon J, Ramsay ME, Whitney CG, Mulholland EK, Goldblatt D, et al. Optimising the use of conjugate vaccines to prevent disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b, Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine. 2008;26(35):4434–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.073.

Andrews NJ, Waight PA, Burbidge P, Pearce E, Roalfe L, Zancolli M, et al. Serotype-specific effectiveness and correlates of protection for the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a postlicensure indirect cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):839–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70822-9.

Center for Diseases Control. The Pink Book. 2020.

Tse A, Tseng HF, Greene SK, Vellozzi C, Lee GM, Group VSDRCAIW. Signal identification and evaluation for risk of febrile seizures in children following trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in the vaccine safety Datalink project, 2010-2011. Vaccine. 2012;30(11):2024–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.027.

Sobanjo-ter Meulen A, Vesikari T, Malacaman EA, Shapiro SA, Dallas MJ, Hoover PA, et al. Safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in toddlers previously vaccinated with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34(2):186–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000000516.

Rupp R, Hurley D, Grayson S, Li J, Nolan K, McFetridge RD, et al. A dose ranging study of 2 different formulations of 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV15) in healthy infants. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(3):549–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2019.1568159.

Platt HL, Greenberg D, Tapiero B, Clifford RA, Klein NP, Hurley DC, et al. A phase II trial of safety, tolerability and immunogenicity of V114, a 15-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, compared with 13-Valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in healthy infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(8):763–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002765.

Schechter NL, Zempsky WT, Cohen LL, McGrath PJ, McMurtry CM, Bright NS. Pain reduction during pediatric immunizations: evidence-based review and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1184–98. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-1107.

Hough-Telford C, Kimberlin DW, Aban I, Hitchcock WP, Almquist J, Kratz R, et al. Vaccine delays, refusals, and patient dismissals: a survey of pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20162127. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2127.

Prymula R, Habib A, Francois N, Borys D, Schuerman L. Immunological memory and nasopharyngeal carriage in 4-year-old children previously primed and boosted with 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV) with or without concomitant prophylactic paracetamol. Vaccine. 2013;31(16):2080–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.044.

Masomian M, Ahmad Z, Gew LT, Poh CL. Development of Next Generation Streptococcus pneumoniae Vaccines Conferring Broad Protection. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8.

McInnes MDF, Moher D, Thombs BD, McGrath TA, Bossuyt PM, and the P-DTAG, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Studies: The PRISMA-DTA Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(4):388–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.19163.

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP (Randomized Controlled trials Checklist). 2018. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. Accessed 25 Jan 2021.

Prymula R, Siegrist CA, Chlibek R, Zemlickova H, Vackova M, Smetana J, et al. Effect of prophylactic paracetamol administration at time of vaccination on febrile reactions and antibody responses in children: two open-label, randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1339–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61208-3.

Prymula R, Esposito S, Zuccotti GV, **e F, Toneatto D, Kohl I, et al. A phase 2 randomized controlled trial of a multicomponent meningococcal serogroup B vaccine (I). Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(7):1993–2004. https://doi.org/10.4161/hv.28666.

Falup-Pecurariu O, Man SC, Neamtu ML, Chicin G, Baciu G, Pitic C, et al. Effects of prophylactic ibuprofen and paracetamol administration on the immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the 10-valent pneumococcal non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae protein D conjugated vaccine (PHiD-CV) co-administered with DTPa-combined vaccines in children: an open-label, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(3):649–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1223001.

Wysocki J, Center KJ, Brzostek J, Majda-Stanislawska E, Szymanski H, Szenborn L, et al. A randomized study of fever prophylaxis and the immunogenicity of routine pediatric vaccinations. Vaccine. 2017;35(15):1926–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.02.035.

Das RR, Panigrahi I, Naik SS. The effect of prophylactic antipyretic administration on post-vaccination adverse reactions and antibody response in children: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106629.

Doedee AM, Boland GJ, Pennings JL, de Klerk A, Berbers GA, van der Klis FR, et al. Effects of prophylactic and therapeutic paracetamol treatment during vaccination on hepatitis B antibody levels in adults: two open-label, randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e98175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098175.

Lopez P, Arguedas Mohs A, Abdelnour Vasquez A, Consuelo-Miranda M, Feroldi E, Noriega F, et al. A randomized controlled study of a fully liquid DTaP-IPV-HB-PRP-T hexavalent vaccine for primary and booster vaccinations of healthy infants and toddlers in Latin America. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(11):e272–e82. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000001682.

Sil A, Ravi MD, Patnaik BN, Dhingra MS, Dupuy M, Gandhi DJ, et al. Effect of prophylactic or therapeutic administration of paracetamol on immune response to DTwP-HepB-Hib combination vaccine in Indian infants. Vaccine. 2017;35(22):2999–3006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.03.009.

Long SS, Deforest A, Smith DG, Lazaro C, Wassilak GF. Longitudinal study of adverse reactions following diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine in infancy. Pediatrics. 1990;85:294–302.

Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33(4):451–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008.

Dimova S, Hoet PH, Dinsdale D, Nemery B. Acetaminophen decreases intracellular glutathione levels and modulates cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and type II pneumocytes in vitro. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37(8):1727–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2005.03.005.

Ryan EP, Malboeuf CM, Bernard M, Rose RC, Phipps RP. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition attenuates antibody responses against human papillomavirus-like particles. J Immunol. 2006;177(11):7811–9. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7811.

Jefferies S, Saxena M, Young P. Paracetamol in critical illness: a review. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14(1):74–80.

Doran TF, De Angelis C, Baumgardner RA, Mellits ED. Acetaminophen: more harm than good for chickenpox? J Pediatr. 1989;114(6):1045–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80461-5.

Brandts CH, Ndjave M, Graninger W, Kremsner PG. Effect of paracetamol on parasite clearance time in plasmodium falciparum malaria. Lancet. 1997;350(9079):704–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02255-1.

Kapiotis S, Sengoelge G, Sperr WR, Baghestanian M, Quehenberger P, Bevec D, et al. Ibuprofen inhibits pyrogen-dependent expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on human endothelial cells. Life Sci. 1996;58(23):2167–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(96)00210-X.

Kim HJ, Lee YH, Im SA, Kim K, Lee CK. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors, aspirin and ibuprofen, inhibit MHC-restricted antigen presentation in dendritic cells. Immune Netw. 2010;10(3):92–8. https://doi.org/10.4110/in.2010.10.3.92.

Ryan EP, Pollock SJ, Murant TI, Bernstein SH, Felgar RE, Phipps RP. Activated human B lymphocytes express cyclooxygenase-2 and cyclooxygenase inhibitors attenuate antibody production. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2619–26. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2619.

Bancos S, Bernard MP, Topham DJ, Phipps RP. Ibuprofen and other widely used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit antibody production in human cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;258(1):18–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.007.

Taddio A, Manley J, Potash L, Ipp M, Sgro M, Shah V. Routine immunization practices: use of topical anesthetics and oral analgesics. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):e637–43. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-3351.

Saleh E, Moody MA, Walter EB. Effect of antipyretic analgesics on immune responses to vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(9):2391–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2016.1183077.

(NHS-UK) NHS. MenB vaccine side effects. 2020.

Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors that influence the immune response to vaccination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32(2). https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00084-18.

Chiappini E, Venturini E, Remaschi G, Principi N, Longhi R, Tovo PA, et al. 2016 update of the Italian pediatric society guidelines for Management of Fever in children. J Pediatr. 2017;180:177–83 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.09.043.

Red Book. Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, 31st Edition. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson M, editors. AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases. 2018. p. 31.

Ezeanolue E, Harriman K, Hunter P, Kroger A, Pellegrini C. General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization. Best Practices Guidance of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/downloads/general-recs.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2021.

WHO. Reducing pain at the time of vaccination: WHO position paper, September 2015-Recommendations. Vaccine. 2016;34:3629–30.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EK participated in the methodology, selection of the studies, analysis of the results, and writing of the initial and final manuscript. GK participated in the methodology, statistical analysis, and modification of the final draft. AM conceived the study, participated in its design, coordination, selection of the studies, initial and final draft of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors do not have competing interests. This study is part of EK MSc Thesis for the “Postgraduate Program in Pediatric Infectious Diseases”.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Koufoglou, E., Kourlaba, G. & Michos, A. Effect of prophylactic administration of antipyretics on the immune response to pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in children: a systematic review. Pneumonia 13, 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-021-00085-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41479-021-00085-8