Abstract

Introduction

In the past several decades, declining incidences of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) have been observed in Chinese populations in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Los Angeles, and Singapore. A previous study indicated that the incidence of NPC in Sihui County, South China remained stable until 2002, but whether age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort affect the incidence of NPC remains unknown.

Methods

Age-standardized rates (ASRs) of NPC incidence based on the world standard population were examined in both males and females in Sihui County from 1987 to 2011. Joinpoint regression analysis was conducted to quantify the changes in incidence trends. A Poisson regression age-period-cohort model was used to assess the effects of age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort on the risk of NPC.

Results

The ASRs of NPC incidence during the study period were 30.29/100,000 for males and 13.09/100,000 for females. The incidence of NPC remained stable at a non-significant average annual percent change of 0.2% for males and −1.6% for females throughout the entire period. A significantly increased estimated annual percent change of 6.8% (95% confidence interval, 0.1%–14.0%) was observed from 2003 to 2009 for males. The relative risk of NPC increased with advancing age up to 50–59 and decreased at ages >60 years. The period effect curves on NPC were nearly flat for males and females. The birth cohort effect curve for males showed an increase from the 1922 cohort to the 1957 cohort and a decrease thereafter. In females, there was an undulating increase in the relative risk from the 1922 cohort to the 1972 cohort.

Conclusions

The incidence trends for NPC remained generally stable in Sihui from 1987 to 2011, with an increase from 2003 to 2009. The relative risks of NPC increased in younger females.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a malignant tumor arising from the epithelial cells that cover the surface and line of the nasopharynx. According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer, NPC is rare in most parts of the world, with an incidence of <1/100,000 person-years for both males and females; however, it is a prevalent malignancy in the Cantonese population in South China (including Hong Kong), with an incidence of >20/100,000 in endemic areas [1]. The incidence varies appreciably in different areas of China; the highest risk areas are in South China, especially in Guangdong Province, whereas low rates are generally observed in North China [2,3]. NPC is more predominant in males, with a male-to-female ratio of >2:1 in most populations [4]. Through much extensive research into the etiology of NPC, epidemiologic evidence suggests that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection and genetic susceptibility are important etiologic factors for the disease [5]. Furthermore, diet and environmental factors might also play significant roles in the pathogenesis of NPC, including the consumption of salted fish and other preserved foods that contain nitrosamines, mutagens, and EBV-reactivating substances [6-9], occupational exposure to formaldehyde [6], and cigarette smoking [10,11].

Primary preventative measures against NPC are difficult because the underlying mechanisms of its development are unclear; therefore, screening, as a secondary preventative measure, is the most effective way by which to prevent NPC in endemic areas. Since 1986, several large-scale, population-based screening programs for NPC have been conducted in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, China using EBV-related antibodies as screening markers [12,13]; however, the effect of screening on the incidence and mortality of the disease has not yet been reported.

In the past several decades, declining incidences of NPC have been observed in Chinese populations in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Los Angeles, and Singapore [14-16]. Some important lifestyle factors such as decreased consumption of salted fish and preserved food and increased westernization of dietary habits might be responsible for the observed decrease in incidence; however, the incidence in South China remained stable [2,17,18]. A previous study indicated that the incidence of NPC in Sihui County remained stable until 2002 [17], but whether age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort affect the incidence of NPC remains unknown.

The purpose of our study was to the determine the secular trend of NPC and to explore the potential effects of age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort on the incidence changes of NPC from 1987 to 2011 in Sihui County, South China.

Methods

Data sources

The data of the local annual population from 1987 to 2011, excluding the migrant population, were obtained from the Sihui Statistics Department. In 1978, the Sihui Cancer Registry was established to collect NPC incidence data on all residents, and since 1987, a full cancer registry system has been developed to collect all cancer incidence data through the three-grade cancer prevention network. Cancer cases were regularly (approximately once a month) reported by local general practitioners to the central hospital of each town. Health specialists assigned by the Sihui Cancer Research Institute collected the reports, recorded the information onto predesigned cards, and checked the quality of the data. Less than 5.0% of the cancer incidence data of Sihui residents who received treatment in hospitals in other cities were obtained from other cancer registries in Guangdong Province. Linkages were made to the local death register system to supplement underreported data when someone who died of cancer was recorded in the death register system but not in the cancer registry system.

The information collected on the cancer reporting cards included name, sex, birth date, cancer site, diagnosis basis, International Classification of Diseases-10th revision (ICD-10) code, date of diagnosis, cause of death, registered identification number, national identification number, and reporting hospital or medical institution.

Statistical methods

NPC cases diagnosed between 1987 and 2011 and their corresponding permanent resident populations in Sihui in each single year were stratified by 5-year age intervals. Sex-specific age-standardized rates (ASRs) of incidence were calculated by the direct method using the world standard population method of Segi (1960) [19].

The Joinpoint Regression Program 4.1.1 (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to fit a series of joined straight lines on a log scale to the trends of annual age-adjusted rates, with the fitted slopes indicating the estimated annual percent change (EAPC) [20]. To quantify the trend over the entire study period, the average annual percent change (AAPC), which is a geometric weighted average of the EAPC trend, was calculated; the weights were equal to the lengths of each segment during a specified fixed interval [21].

Log-linear Poisson regression was performed to investigate the effects of age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort on NPC incidence for each sex. NPC is too infrequent to evaluate before age 30 and after age 75; thus, NPC patients younger than 30 and not younger than 75 were not included in the analysis. NPC cases were categorized into 9 age groups (30–34 to 70–74), 5 period groups (1987–1991 to 2007–2011), and 13 birth cohort groups (1915–1919 to 1975–1979) with a 5-year interval. The birth cohort groups were named by the mid-year of each cohort; for example, the 1915–1919 birth cohort group was named the 1917 cohort. If the variables in the Log-linear Poisson regression were not independent from each other, a non-identifiability problem appeared. To overcome the non-identifiability problem, individual records of cases were used to form a three-way table of age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort [22,23]. Several models—age alone, period alone, cohort alone, age-period, age-cohort, period-cohort, and age-period-cohort (APC)—were generated. The goodness of fit for the specified model was evaluated by the deviance: the closer the deviance was to the degree of freedom, the better the model. The 30–34 age group, the 1987–1991 period group, and the 1942 cohort group were used as the reference groups, given their greater stability compared with other groups. Based on these reference groups, the estimated corresponding relative risks (RRs) could be calculated with the exponentials of regression coefficients of other age, period, and cohort groups; however, because the first and last cohort groups each contained only one datum and the effect estimates were uncertain, the effects for these groups were not presented. The results were considered significant with a two-sided P value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

NPC incidence in Sihui County

Over the 25-year study period (1987–2011), 2,151 new NPC cases were identified (1,494 males and 657 females) in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, China. Of all these NPC cases newly diagnosed between 1987 and 2011, 85.1% of cases were histologically verified, and only 1.9% had death certificates; the mortality to incidence ratio was 0.641. The crude incidences were 22.37/100,000 for the total population, 30.38/100,000 for males, and 13.99/100,000 for females between 1987 and 2011. The corresponding ASRs were 21.73/100,000 for the total population, 30.29/100,000 for males, and 13.09/100,000 for females. The overall male-to-female ratio of the annual ASR of NPC incidence was 2.3:1 (Table 1). Figure 1 shows that the incidence of NPC in Sihui County between 1988 and 2011 was fluctuated within a small range for both sexes.

The age-standardized rates (ASRs) of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) incidence for males and females in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, South China from 1987 to 2011. The ASRs were calculated using the world standard population method of Segi (1960). The NPC incidence in Sihui County fluctuates within a small range for both sexes.

Change tendency of NPC incidence

Figure 2 depicts the annual percent change in NPC incidence stratified by sex in Sihui County between 1987 and 2011. For males, there was a slight increase (EAPC, 2.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], −0.6%–5.8%) from 1987 to 1996. From 2003 to 2009, there was a significant increase, with an EAPC of 6.8% (95% CI, 0.1%–14.0%). The EAPC for females was similar to that of males, but no significant changes were observed in different periods. Throughout the entire 25-year period, the incidence of NPC remained stable; the AAPCs were 0.2% for males and −1.6% for females (P > 0.05).

Annual percent changes in NPC incidence stratified by sex in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, South China from 1987 to 2011 with Joinpoint regression. EAPC, estimated annual percent change. ^, P < 0.05. From 2003 to 2009, the NPC incidence for males significantly increased, with an EAPC of 6.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.1%–14.0%). The EAPCs during other periods for both sexes were not significant.

Age-period-cohort effect on NPC incidence

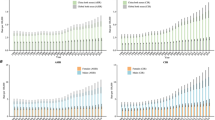

Table 2 shows that the APC model fit better than other models for both males and females because the deviance in this model was the closest to the degree of freedom. The effects of age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort on the risk of NPC for males and females are illustrated in Table 3. Both males and females shared a similar age-effect pattern. The risk of NPC increased with advancing age up to 50–59 and decreased at ages >60 years (Figure 3A). The curves of period effect on the risk of NPC were virtually flat for both sexes (Figure 3B). The curve for males by birth cohort showed that the RRs increased from the 1922 cohort to the 1957 cohort and decreased after the 1957 cohort; for females, the RRs increased with undulation from the 1922 cohort to the 1972 cohort and peaked near the 1972 cohort (Figure 3C).

Age, period, and cohort effects obtained from the Poisson age-period-cohort model of NPC in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, South China from 1987 to 2011. A, both males and females shared a similar age-effect pattern. The risk of NPC increased with advancing age up to 50–59 years and decreased at ages >60 years. B, the curves of period effect on the risk of NPC were virtually flat for both sexes. C, the birth cohort curve for males showed that the relative risks of NPC increased from the 1922 cohort to the 1957 cohort and decreased after the 1957 cohort. For females, the relative risks increased with undulation from the 1922 cohort to the 1972 cohort and peaked near the 1972 cohort.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that the secular trend of NPC incidence remained stable with only slight fluctuation in Sihui County from 1987 to 2011. A similar incidence trend was observed in other regions of Guangdong and Guangxi Provinces, China [2,17]; however, the incidence of NPC has declined steadily in Hong Kong and Taiwan over recent decades [14,24]. The migrant epidemiologic studies conducted in Chinese populations in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Los Angeles showed a rapid reduction in NPC incidence from 1973 to 1997 in both males and females. In Singapore, the incidence of NPC in Chinese populations dropped from 1993 to 1997 in both sexes [15]. The phenomenon of heterogeneous secular trends of NPC incidence among different areas and populations might be partially explained by the diversity of environmental risk factors in different areas.

Some important lifestyle factors for NPC, such as the consumption of salted fish and preserved food and were expected to decrease as environmental changes and the westernization of dietary habits became more prevalent. This is presumed to be the reason for the decline in NPC incidence in Hong Kong and Taiwan [14,24]. During recent decades, with the rapid upward trend in the economy of Sihui County, changing lifestyles, dietary habits, and living conditions were also remarkable; however, we observed that the secular trend in NPC incidence remained stable until 2011. This coincided with the findings of other researchers [2,17,18]. We presumed that this trend might be because the effects of the changes in environmental factors lag behind the incidence of NPC or because some unknown environmental factors still exist in South China.

Our Joinpoint regression data suggested that the incidence of NPC increased from 1987 to 1999 for females and from 1987 to 1996 for males. Another significant increase for males appeared in 2003–2009, but each increase was followed by a decrease. These fluctuations within different periods are partly because of the two population-based NPC screening programs conducted in Sihui County: the first recruited participants from four towns in 1987, 1992 until 1997 [12]; the second was an ongoing screening project, of which the first round was conducted in six towns from 2008 to 2009 [13]. More early-stage NPC cases were detected, which indicated that the incidence increased during the screening period.

The age effect reflects physiologic differences among different age groups in the susceptibility to a given disease. In the present study, we found that the risk of NPC increased with age until 55-59 years and decreased thereafter; this finding was consistent with data from previous studies in endemic areas [25]. The period effect usually reflects the roles of multiple factors on the given disease that equally affect all age groups during a period of time. In our study, the introduction of new diagnostic techniques, changes in environmental factors, and modulation of lifestyles together might result in the unchanged effect by period. The birth cohort effect on NPC might result from different environmental exposure levels in different birth cohorts. The effect of lifestyle factors, which might be fixed early in life, is most likely reflected by the cohort effect [24]. Birth cohort-stratified incidences in males and females showed two trends. In males, the cohort effect is curved, with NPC risks increasing from the earliest cohorts, peaking in the 1957 cohort, and decreasing in younger cohorts from the 1957 cohort to the 1972 cohort; however, the RRs increased with undulation in the 1972 cohort of females. We presumed that the increased NPC risk in the younger female cohort might be due to increased cigarette smoking. A meta-analysis reported that cigarette smoking increased the risk of NPC [11]. Evidence from several studies conducted in Guangdong Province showed that the smoking rate was higher in males than in females but the smoking rate in males has decreased, whereas that in females has increased in recent years [26,27]. Moreover, exposure to secondhand smoke was more prevalent in females than in males [26,27].

There are several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results from this study. With respect to the statistical methods, when using the APC model analysis, the sample size appeared too small to achieve robust estimates; thus, the age, diagnosis period, and birth cohort effects should be interpreted with caution. In addition, our study lacked adequate data to determine the incidence trend by histological subtype because the detailed histological subtype data for each cancer case were not included on the cancer report card in Sihui County. In the future, it might be better to analyze the incidence trend by different histological subtypes of NPC if the relevant data can be collected.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the incidence trends for NPC remained generally stable in Sihui County from 1987 to 2011, with an increase during 2003–2009. The RRs of NPC in younger female birth cohorts increased; the underlying reasons for this will be further explored. Because NPC remains a significant health burden in Sihui County, it is worthwhile to conduct epidemiologic studies on genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and their interactions.

References

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90.

**e SH, Gong J, Yang NN, Tse LA, Yan YQ, Yu IT. Time trends and age-period-cohort analyses on incidence rates of nasopharyngeal carcinoma during 1993–2007 in Wuhan, China. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36:8–10.

Yang WS, Yang C, Zheng JW, Gao J, Zhang W, Zhang ZY, et al. Time trend analysis of incidence rate for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in urban Shanghai. Zhonghua Liu **ng Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2009;30:1171–4 [in Chinese].

Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1765–77.

Chan AT, Teo PM, Johnson PJ. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1007–15.

Guo X, Johnson RC, Deng H, Liao J, Guan L, Nelson GW, et al. Evaluation of nonviral risk factors for nasopharyngeal carcinoma in a high-risk population of southern China. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2942–7.

Gallicchio L, Matanoski G, Tao XG, Chen L, Lam TK, Boyd K, et al. Adulthood consumption of preserved and nonpreserved vegetables and the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1125–35.

Shao YM, Poirier S, Ohshima H, Malaveille C, Zeng Y, de The G, et al. Epstein-Barr virus activation in Raji cells by extracts of preserved food from high risk areas for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 1988;9:1455–7.

Poirier S, Bouvier G, Malaveille C, Ohshima H, Shao YM, Hubert A, et al. Volatile nitrosamine levels and genotoxicity of food samples from high-risk areas for nasopharyngeal carcinoma before and after nitrosation. Int J Cancer. 1989;44:1088–94.

Cheng YJ, Hildesheim A, Hsu MM, Chen IH, Brinton LA, Levine PH, et al. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:201–7.

Xue WQ, Qin HD, Ruan HL, Shugart YY, Jia WH. Quantitative association of tobacco smoking with the risk of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a comprehensive meta-analysis of studies conducted between 1979 and 2011. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:325–38.

Cao SM, Liu Z, Jia WH, Huang QH, Liu Q, Guo X, et al. Fluctuations of Epstein-Barr virus serological antibodies and risk for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a prospective screening study with a 20-year follow-up. PLoS One. 2011;6, e19100.

Liu Z, Ji MF, Huang QH, Fang F, Liu Q, Jia WH, et al. Two Epstein-Barr virus-related serologic antibody tests in nasopharyngeal carcinoma screening: results from the initial phase of a cluster randomized controlled trial in southern China. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177:242–50.

Lee AW, Foo W, Mang O, Sze WM, Chappell R, Lau WH, et al. Changing epidemiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong over a 20-year period (1980–99): an encouraging reduction in both incidence and mortality. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:680–5.

Luo J, Chia KS, Chia SE, Reilly M, Tan CS, Ye W. Secular trends of nasopharyngeal carcinoma incidence in Singapore, Hong Kong and Los Angeles Chinese populations, 1973–1997. Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:513–21.

Sun LM, Epplein M, Li CI, Vaughan TL, Weiss NS. Trends in the incidence rates of nasopharyngeal carcinoma among Chinese Americans living in Los Angeles County and the San Francisco Metropolitan area, 1992–2002. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:1174–8.

Jia WH, Huang QH, Liao J, Ye W, Shugart YY, Liu Q, et al. Trends in incidence and mortality of nasopharyngeal carcinoma over a 20–25 year period (1978/1983-2002) in Sihui and Cangwu counties in southern China. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:178.

Wei K, Xu Y, Liu J, Zhang W, Liang Z. No incidence trends and no change in pathological proportions of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Zhongshan in 1970–2007. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11:1595–9.

Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, Storm H, Ferlay J, Heanue M, et al. Cancer incidence in five continents volume IX. Lyon: IARC Scientific Publications; 2007. p. 99–100.

Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19:335–51.

Clegg LX, Hankey BF, Tiwari R, Feuer EJ, Edwards BK. Estimating average annual percent change in trend analysis. Stat Med. 2009;28:3670–82.

Robertson C, Boyle P. Age, period and cohort models: the use of individual records. Stat Med. 1986;5:527–38.

Robertson C, Boyle P. Age-period-cohort analysis of chronic disease rates. I: Modelling approach. Stat Med. 1998;17:1305–23.

Hsu C, Shen YC, Cheng CC, Hong RL, Chang CJ, Cheng AL. Difference in the incidence trend of nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal carcinomas in Taiwan: implication from age-period-cohort analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:856–61.

**e SH, Yu IT, Tse LA, Mang OW, Yue L. Sex difference in the incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Hong Kong 1983–2008: suggestion of a potential protective role of oestrogen. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:150–5.

Zeng S, Lin L. Study on smoking pattern and related factors among residents aged over 15 years in Guangdong province. Zhonghua Liu **ng Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2000;21:134–6 [in Chinese].

Wang JP, Guo XK. Impact of electronic wastes recycling on environmental quality. Biomed Environ Sci. 2006;19:137–42.

Acknowledgment

We appreciate all staff of the Sihui Cancer Registry for their work on registration and follow-up.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ZLF designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. LYH, LW, and HQH carried out the data collection and follow-up. XSH and CSH contributed to the data check and statistical analysis. LQ and CSM conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Li-Fang Zhang and Yan-Hua Li contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, LF., Li, YH., **e, SH. et al. Incidence trend of nasopharyngeal carcinoma from 1987 to 2011 in Sihui County, Guangdong Province, South China: an age-period-cohort analysis. Chin J Cancer 34, 15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40880-015-0018-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40880-015-0018-6