Abstract

Forecasting changes in stock prices is extremely challenging given that numerous factors cause these prices to fluctuate. The random walk hypothesis and efficient market hypothesis essentially state that it is not possible to systematically, reliably predict future stock prices or forecast changes in the stock market overall. Nonetheless, machine learning (ML) techniques that use historical data have been applied to make such predictions. Previous studies focused on a small number of stocks and claimed success with limited statistical confidence. In this study, we construct feature vectors composed of multiple previous relative returns and apply the random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and long short-term memory (LSTM) ML methods as classifiers to predict whether a stock can return 2% more than its index in the following 10 days. We apply this approach to all S&P 500 companies for the period 2017–2022. We assess performance using accuracy, precision, and recall and compare our results with a random choice strategy. We observe that the LSTM classifier outperforms RF and SVM, and the data-driven ML methods outperform the random choice classifier (p = 8.46e−17 for accuracy of LSTM). Thus, we demonstrate that the probability that the random walk and efficient market hypotheses hold in the considered context is negligibly small.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stock market forecasting is extremely challenging given the nonlinear and non-stationary variations observed in stock market data. The problem is further complicated by external factors such as economic circumstances, political events, and investor sentiment. The random walk hypothesis proposed by Fama (1995) assumes that stock price changes are basically stochastic; therefore, attempts to accurately predict future stock prices will fail. Similarly, the efficient market hypothesis (Malkiel 1989) states that future changes in stock prices cannot be predicted from previous data. However, many economists and stock market participants believe that stock prices are at least partially predictable because price changes tend to repeat themselves due to investors’ collective and systematic activities (Shah et al. 2019; Chong et al. 2017).

Previous studies apply machine learning (ML)-based methods to predict stock prices. For example, a study (Kumar et al. 2016) predicts a 1-day ahead closing price direction for 12 stock indices using a variety of technical indicators as inputs to a proximal support vector machine (PSVM). The authors of Aloraini (2015) predict the daily opening price direction for 11 companies listed in Saudi Arabia’s stock market. The study (Nayak et al. 2021) forecasts close price percentage changes in two Indian benchmark indices using a combined method, i.e., SVM with a rough set model. The authors show that the hybrid method outperforms a decision tree, Naive Bayes, and artificial neural networks (ANN) in terms of accuracy using the selected datasets. In Ruxanda and Badea (2014), ANNs are built using lagged prices and macroeconomic indicators to forecast 1-day ahead values for the Romanian BET index.

These studies attempt to predict the direction of future stock prices. We identify two deficiencies in this approach: (1) the studies focus on stock price movements rather than relative returns, and (2) they analyze a relatively small number of companies, which is not sufficient to provide statistically meaningful conclusions.

In this study, we investigate a relative stock return classification problem that would allow stock selection based on time series price data over the period from 2017 to 2022 for all of the stocks in the S&P 500 index. We compare the effectiveness of our ML-based approach with that of random stock picking.

This remainder of this study is organized as follows. "Related work" section presents a review of previous related work. In "Data and methods" section, we define the problem and specify the input features, class labels, and machine learning (ML) predictive models used in our analysis. The experimental results and findings for the S&P 500 stocks are presented in "Results" section along with a comparison with a random choice (RC) classifier. "Conclusions" section concludes the study.

Related work

In general, stock market analyses can be divided into two categories based on the type of data used: fundamental and technical analysis. In a fundamental analysis (Heo and Yang 2016), a stock price is estimated based on the company’s earnings, revenues, dividends, and other measures of the company’s financial performance. Chen et al. (2017) use financial indicators such as operating income, return on assets, and pretax income to choose stocks in the Taiwan stock market. Another study (Li et al. 2022) predicts 1-day-ahead closing prices of stocks trading on the Shanghai stock exchange using 35 features including four fundamental indicators, namely price-to-earnings ratio, price-to-book ratio, price-to-sales ratio, and price-to-cash flow ratio. Another study (Yuan et al. 2020) applies various fundamental indicators including net profit, dividends, and return on equity, to predict stock returns in China’s A-shares market using support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and artificial neural network (ANN) methods.

A technical analysis (Nazario et al. 2017) uses indicators computed from historical market data, such as prices and volumes, to forecast stock prices. Several studies (AI-Shamery and AI-Shamery 2018; Lin 2018; Patel et al. 2015) use technical indicators such as exponential moving average (EMA), relative strength index (RSI), stochastic oscillator, and rate of change to predict the direction of various stock markets. In Picasso et al. (2019), ten common technical indicators are used to generate buy and sell signals for a trading strategy involving 20 companies in the NASDAQ 100 index. Dai et al. (2020) introduces and applies new technical indicators based on an EMA and RSI to improve the predictability of certain trading strategies.

Some of the most basic forecasting methods used in making stock market predictions are statistical models such as the autoregressive moving average (ARMA) (Lv et al. 2022), which are widely applied to predict changes in stock market indexes from stationary time series data. For short-term stock market predictions, the integrated model known as autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) (Jarrett and Schilling 2008) is also popular. One study applies ARIMA in combination with the artificial bee colony (ABC) (Kumar et al. 2022) algorithm for one-step ahead and multi-step ahead predictions of prices for stock trading on India’s National Stock Exchange (NSE) and Bombay Stock Exchange. SVM has become a popular ML technique for both regression and classification problems. The authors in Nabi et al. (2019) use classifiers to predict the direction of monthly closing prices of 10 stocks that trade on the NASDAQ exchange and find that SVM performs best for binary classifications, based on average accuracy across their sample. Another study (Siddique and Panda 2019) applies SVM as a regressor to forecast the next-day closing prices of TaTa Motors. In Chen and Hao (2017), the authors apply SVM to predict the direction of two Chinese stock market indices for the next 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 days based on nine technical indicators. They examine the relative importance of each indicator using the information gain approach and conclude that the SVM method is robust and has the strong predictive capability for their chosen indices. The authors of Kou et al. (2021) apply four feature selection methods, including the information gain approach, to determine the optimal subset of features to use in predicting bankruptcies among small- and medium-sized enterprises. They discuss the importance of the feature selection process in improving the performance of the prediction model. Using popular technical indicators as inputs to the SVM model, the authors of Henrique et al. (2018) predict the prices of various stocks in the Brazilian, U.S., and Chinese markets. The results show that SVM with a linear kernel performs better than other types of kernels. Another study (Nti et al. 2020) combines SVM with genetic algorithms (GAs) to examine the performance of two stocks from the Ghana stock market over the last 11 years in forecasting 10-day ahead stock price movements.

The future direction of stock price movements has also been predicted using tree-based ensemble methods (Basak et al. 2019). Several ensemble methods, including RF, XGBoost, bagging, AdaBoost, extra trees, and voting classifiers (Ampomah et al. 2020), have been applied to predict the prices of stocks trading on the NYSE, NASDAQ, and NSE. Extra trees provides the greatest average F1 score for all stocks in the sample, although each classifier achieves varying accuracy values for different stocks.

Among the various tree-based approaches, RF (Breiman 2001) has received considerable attention because it displays low variance, provides feature importance scores, and is applicable in both regression and classification problems. Based on 10 years of data on four companies, the authors of Patel et al. (2015) examine the overall performance of four prediction models, ANN, SVM, RF, and Naive Bayes, and find that RF outperforms the other models in terms of trend predictions. Another study (Hong**ng et al. 2022) applies a wide range of ML models to the highly volatile Pakistan stock market using 13 years of data and concludes that RF is best suited for nonlinear approximations.

RF can also be used as a feature selection technique, resulting in higher accuracy for price and return predictions. The study (Labiad et al. 2016) uses the mean decrease in impurity and mean decrease in accuracy provided by RF to select features to use in forecasting very short-term variations, i.e., 10 min in advance of the Moroccan stock market. The authors of Kumar et al. (2016) apply four feature selection techniques including RF to choose the best features among 55 technical indicators to use with PSVM to predict 1-day ahead closing prices. For all selected datasets, RF-PSVM is the only hybrid model that outperforms the PSVM model in terms of accuracy. As a result, the RF model has consistently been a top predictive model in numerous stock market applications. Alternative feature selection methods are applicable to stock market prediction and other financial sectors. In Xu et al. (2024), the authors apply the wrapper method and GAs to select features in assessing both profits and risks of credit scoring models for North American banks.

Another study applies a convolutional neural network (CNN) (Chandar 2022) method based on price charts converted from ten technical indicators extracted from historical data. The authors evaluate performance in terms of accuracy and F1 measures for companies listed on the NASDAQ and NYSE. To forecast short-term stock prices using price charts and stock fundamentals, the study (Liu et al. 2022) uses a deep neural network (DNN) and concludes that price trends outweigh fundamental factors such as the price-to-earnings ratio in predicting future price movements. In Aasi et al. (2021), the authors apply a long short-term memory (LSTM) model to predict Apple’s closing stock price 1 week in advance using nine sentiment analysis features, including Google trends, tweets, and comments from SeekingAlpha’s news.

Hybrid models are among the most widely used ML techniques for forecasting stock prices because they produce more accurate results compared to individual approaches. Instead of using a single data set, the authors of study (Chen et al. 2022) clusters stock prices of 16 listed banks using K-means clustering to find banks with similar price patterns. They then train an LSTM model based on the clustered data. Their results show that the hybrid model of K-means and LSTM yields lower error values than the LSTM model with a single bank of data. The study (Srivinay et al. 2022) also proposes a hybrid stock prediction model using the prediction rule ensembles (PRE) technique, which creates a set of prediction rules to produce various decision trees based on logical statements and the DNN method. The authors use moving average technical indicators as inputs and the average values from the PRE and DNN prediction models as the final predictions. They obtain lower RMSE values for the Indian stock market and conclude that the proposed hybrid model is superior to the DNN and ANN individual models.

A previous study (Chen et al. 2020) compares the RF, SVM, and ANN methods in predicting the return of the S&P 500 index. The authors use 10 technical indicators as inputs and apply each ML method to make predictions. Of the three approaches, RF produces the best results with respect to both daily returns and cumulative returns over the entire sample period, 2014 to 2018. Another study (Krauss et al. 2017) applies RF, gradient-boosted-trees, DNN, and an ensemble of these models to perform a binary classification of 1-day ahead simple returns of all stocks in the S&P 500. The authors train each model using 1-year lagged returns for each stock in the index, then predict their 1-day ahead returns. They find the proposed ensemble approach outperforms all of the individual models in terms of accuracy. The authors of Fischer and Krauss (2018) apply LSTM to a binary classification problem in forecasting 1-day ahead returns for all of the stocks in the S&P 500. Using data from 1992 to 2015, they compare LSTM to other ML methods including DNN, logistic regression classifier, and RF. In Gaspareniene et al. (2021), the authors predict the monthly value of the S&P 500 index using the decision tree, RF, and feedforward neural network methods. They find that RF is 19% more accurate than a baseline model that uses linear regression. By combining fundamental and technical data, one study (Singh Khushi 2021) predicts the direction of changes in closing prices for the S&P 500 stocks by 1% up to 10 days in the future.

The majority of existing studies attempt to predict closing prices or simple returns on an hourly, daily, weekly, or monthly basis, applying a variety of forecasting models, datasets, and evaluation criteria. We observe that with respect to applying ML predictive models to stock markets, RF and SVM are the most widely applied forecasting methods because of their flexibility in both classification and regression problems. RF is one of the most popular methods as it performs well in terms of prediction results due to its favorable characteristics including generalizability, simplicity, robustness, and low variance. In this study we focus on predicting relative returns, i.e., the difference between the return for an individual stock and the return of the market index, rather than absolute prices or returns. Therefore, we examine how well an ML method can forecast future relative returns using previous relative returns as inputs to the ML model. We show that ML-based classification is superior to random stock selection using all S&P 500 companies for the period 2017–2022.

Data and methods

Problem definition

We describe a two-class classification problem in which we aim to identify stocks that will generate a relative return above a certain threshold (2%) within a certain period of time (ten trading days, referred to as the horizon). We train stock-specific and time-specific classifiers using feature vectors composed of relative returns. Then, we use each classifier to predict whether the corresponding stock will experience a relative return greater above the 2% threshold over the following ten days (class 1), or not (class 0).

Definitions and computation of features and feature vectors

We obtain daily closing prices for the 505 stocks in the US S&P 500 index for the 5-year period from January 01, 2017 to January 01, 2022 from Yahoo Finance (https://finance.yahoo.com/). We used 494 stocks in our experiments because our data source did not offer prices for 11 stocks before 2020. Examples of S&P 500 companies in different sectors are shown in Table 1. The original datasets include the date, the open, high, low, and closing prices, and trading volume. Previous studies (Rana et al. 2019; Al Wadi et al. 2018) show that closing price is the most significant among these inputs, and we also use closing prices to compute features in our study.

In stock market forecasting, different types of inputs have been used, including previous price values, technical indicators derived from those previous price values, and fundamental indicators. Deciding which type of input to use is a key aspect of making successful predictions. In this study, we explore how effectively previous relative returns over various time periods, such as a day, week, month, quarter, and year, can predict future relative returns. We define and compute the returns of an individual stock at time i relative to time i − k as follows:

where P (i) is the closing price of the stock at time i (current day) and P (i − k) is the closing price of the same stock at some previous day i − k, k = 260, 180, 150, 120, 100, 80, 60, 40, 20, 15, 10, 5, and 1.

We also use Eq. 1 to compute the returns of the S&P 500 index, RSP (i,k). To relate changes in the returns of individual stocks to the rest of the market, we compute relative returns X (i,k) as the differences between stock and index returns:

We use 13 relative returns of a stock to form a 13-dimensional feature vector that characterizes this stock at time i for each value of k: X (i, 260), X (i, 180), X (i, 150), X (i, 120), X (i, 100), X (i, 80), X (i, 60), X (i, 40), X (i, 20), X (i, 15), X (i, 10), X (i, 5), and X (i, 1). Table 2 shows examples for one stock. We use such feature vectors as inputs to a trainable classifier for a stock using a machine learning approach.

Definition and computation of the class labels

We assign a binary class label to each feature vector depending on the relative returns of the given stock over the 10 trading days following the current day. If one of the relative returns over the next 10 days is larger than the specified threshold d, we set the class label y(i) to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0:

Table 3 shows the proportion of class 1 labels assigned for various stocks using various values of threshold d. We use the average value of the observed proportion of class 1’s across all stocks and all trading days as an approximation of the probability p(1) of class 1. We observe that p(1) decreases as d increases. For example, for d = 0.3%, p(1) = 0.77, while for d = 10%, p(1) = 0.06. For d = 2%, the two classes are roughly balanced, with p(1) = 0.49 and p(0) = 0.51. Therefore, to avoid machine learning problems typically associated with unbalanced classes, we use the value d = 2%.

The economic rationale for using a positive threshold d is to find a way to select stocks that outperform the index. Correctly predicting the class for a given stock on day t can be used as a signal to buy the stock if it is predicted to belong to class 1, to obtain a relative return d (d > 0) during the subsequent ten trading days. An investor who follows this rule may decide to sell the stock and lock in the relative return d as soon as the threshold d is reached, or keep the stock if it is again predicted to belong to class 1 on the day its relative return reaches the threshold d. Assuming the same fixed amount is invested in each stock predicted to belong to class 1, a system that always gives correct predictions would yield a total relative return across all stocks over a period of 10 days equal to the product p(1)d of p(1) and d. For example, if d = 0.3% and p(1) = 0.77, p(1)d = 0.231%, in this example, the proportion of investable stocks, i.e., p(1), is high but the relative return d per stock is low. In contrast, for d = 10% and p(1) = 0.06, p(1)d = 0.6%, the relative return per stock is high but the proportion of investable stocks is low. For d = 2% and p(1) = 0.49, p(1)d = 0.98%. The total relative return peaks around the value of d for which an approximate class balance is achieved, in our case d = 2%.

The value d for which an approximate class balance is reached is related to the time horizon, i.e., the number of trading days considered. The larger the number of trading days over which the stock must reach a relative return threshold d, the larger the threshold d needed to achieve a class balance. In our study, the threshold value d = 2% for which an approximate class balance is achieved is determined by the number of trading days we chose (i.e., 10 days).

Sliding window approach to training and testing

We divide the dataset into training and test sets using a sliding window approach (Fig. 1). For each stock, we use 12 consecutive months (253 consecutive trading days) to train a classifier. After a gap of ten trading days, we use the following month (21 trading days) to test that classifier’s performance. Data from 2017 are used to compute the feature vectors and the first training period is from January 16, 2018 to January 16, 2019. The class labels depend on the relative returns over the next 10 days. Therefore, the first day of each test period starts 10 days after the last day of the corresponding training period. The first test period is from February 01, 2019 to March 04, 2019. After that, the window is shifted by 1 month and a new classifier is trained and then tested. This process is repeated 23 times, resulting in 483 predictions (= 21 * 23) for each stock in the S&P 500.

Random forest (RF) classifier

We use RF as a classifier, constructed as follows. For each training set, we generate multiple bootstrapped datasets, each one the same size as the training set, but using feature vectors randomly selected from the training set by row sampling with replacement. For each individual bootstrapped dataset, we grow a decision tree using that dataset and applying a random subset of features at each split until the tree is fully grown or a stop** criterion is reached. For each RF we train, we use 1000 trees, with a maximum of 13 features and a maximum depth of 5 per decision tree. We implemented the RF classifier in the scikit-learn environment (Pedregosa et al. 2011) in Python 3.7. For each stock, we train 23 random forests corresponding to the 23 positions of the sliding window. After training an RF for a given stock and position of the sliding window, we test its performance for the corresponding test set. The class assigned to a certain feature vector by the RF is computed by a majority vote among the individual trees in the RF.

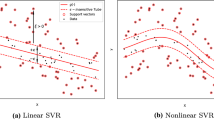

Support vector machines (SVM) classifier

We also apply an SVM as a classifier. For each training set, we construct an SVM classifier using the scikit-learn environment (Pedregosa et al. 2011). After training an SVM classifier for a given stock and position in the sliding window, we evaluate its performance for a corresponding test set. We test SVM classifiers based on different kernel functions, including linear, radial basis function (RBF), and polynomial with a regularization parameter C = 1.0. We find that the kernel RBF produces the best results (higher accuracy values) for most of the stocks in our sample.

Long short-term memory (LSTM) classifier

To consider the temporal sequence of the data, we apply the LSTM method as a classifier using the same training and test datasets used for the RF and SVM classifiers. To configure our LSTM network, we tune several important hyperparameters, including the number of units or hidden dimensions, LSTM layers, batch sizes, and the number of epochs (iterations). Our initial LSTM network setup consisted of a single layer with a small number of units and iterations. Subsequently, through a series of experiments and fine-tuning based on overall performance across all 494 stocks, we achieve the highest accuracy, precision, and recall by configuring the network with three LSTM layers (each comprising 260 units), two dropout layers with a dropout rate of 0.2, one Dense layer, a batch size of 64, an Adam optimizer, and a sigmoid activation function, training it for 200 epochs. We develop the LSTM classifier using Keras, which is built on top of the Google TensorFlow library (https://www.tensorflow.org/).

Results

We use accuracy, precision, and recall to measure classification performance:

where TP = number of true positives, TN = number of true negatives, FP = number of false positives, FN = number of false negatives.

We compute values for A, P, and R for each stock, based on the 483 trading days used for testing and the 23 classifiers (RF, SVM, or LSTM) trained for that stock for the 21 different positions of the sliding window. We compare the classification performance for RF and SVM and find that the two classifiers perform similarly for most stocks. We apply single-sided paired t tests to the set of values for ARF − ASVM, PRF − PSVM, and RRF − RSVM obtained for different stocks to test whether their means are positive. We obtain t = − 1.93, p = 0.054 for accuracy, t = 2.2, p = 0.03 for precision, and t = 3.5, p = 0.0005 for the recall values. Regarding accuracy and precision, the p values are not small enough to conclude that either of the two methods performs better than the other. RF outperforms SVM in terms of recall (p = 0.0005). Therefore, we next compare RF’s classification performance to LSTM and apply single-sided paired t-tests to the set of values of ALSTM − ARF, PLSTM − PRF, and RLSTM − RRF obtained for each stock to test whether their means are positive. We obtain t = 2.88, p = 0.004 for accuracy, t = 4.05, p = 5.8e−05 for precision, and t = 8.37, p = 6.04e−16 for recall values. Therefore, across all three metrics (accuracy, precision and recall), the LSTM classifier demonstrates superior performance compared to both RF and SVM classifiers. We present the accuracy, precision, and recall values of the best classifier, LSTM, in the columns labeled ALST M, PLST M, and RLST M in Tables 6, 7, and 8, respectively.

Next, we compare the LSTM classification approach with a random choice (RC) classifier. For an RC classifier with probability p(1) of class 1, we can show that

where n is the number of trading days used for testing.

Substituting Eqs. 7–10 for TPRC, TNRC, FPRC, and FNRC in Eqs. 4–6, we obtain:

For p(1) = 0.49, we obtain:

Our sample period covers both 2019 (the year before the COVID pandemic), and 2020 and 2021 (during the COVID pandemic). Therefore, we measure the performance of the LSTM classification and the RC classifier independently for each year to analyze different market conditions and periods. We determine the values of p(1) for each of these years separately, as shown in Table 4.

Similarly, we determine values for accuracy, precision, and recall for each of these years (Table 5). The LSTM classifier achieves the highest values for 2020 and the lowest values for 2019. For the entire sample period from 2019 to 2021, the LSTM classification approach outperforms the RC classifier in terms of all mean values for accuracy, precision, and recall.

Tables 6, 7, and 8 show the mean values for accuracy, precision, and recall computed across all stocks as well as the “pooled values” computed from the values of TP, TN, FP, and FN across all stocks. The pooled values of ALSTM, PLSTM, and RLSTM across all stocks and test periods are larger than their counterparts ARC, PRC, and RRC for a random choice classifier. The same is true for the mean values of accuracy, precision, and recall.

To determine whether we can reliably claim that the LSTM classification approach outperforms the random choice classifier, we apply single-sided paired t tests to the sets of values of ALSTM − ARC, PLSTM − PRC, and RLSTM − RRC obtained for individual stocks. We find that the means of these differences are positive with t = 8.63, p = 8.46e−17 for accuracy, t = 2.64, p = 0.008 for precision, and t = 12.57, p = 1.29e−31 for recall. Thus, we can claim with very high confidence that the LSTM classification approach outperforms random choice classification regarding all performance measures (accuracy, precision and recall).

In Figs. 2, 3, and 4, box-whisker plots and histograms illustrate the distribution of accuracy, precision, and recall differences between an LSTM and a RC classifier across all stocks.

Conclusions

In this study, we use multiple historical relative returns as input features of RF, SVM, and LSTM classifiers to identify stocks that will generate relative (to the S&P 500 index) returns that exceed a certain threshold (2%) within a certain period of time (time horizon of ten trading days). Our experimental results, obtained using data for 494 of the S&P 500 stocks from January 2017 to January 2022 show that

-

RF and SVM provide similar classification accuracy and precision. RF outperforms SVM in terms of recall (p = 0.0005).

-

The LSTM classifier performs better than RF and SVM based on the mean values of accuracy, precision, and recall over all stocks.

-

The LSTM classifier also outperforms a random choice classifier in terms of the mean values of accuracy, precision, and recall over all stocks, with corresponding t-statistics and p-values of t = 8.63, p = 8.46e−17 for accuracy, t = 2.64, p = 0.008 for precision, and t = 12.57, p = 1.29e−31 for recall.

-

The extremely small p-values for accuracy, precision, and recall show the probability that the random walk hypothesis and efficient market hypothesis being true in the considered problem is negligibly small.

-

ML classifiers that use previous relative returns as inputs offer advantages for stock picking over random selection.

In future research, we will use different types of features, including various technical indicators, in our analysis. We also intend to explore the impact of different training and test periods. Furthermore, we will extend our forecasting analysis to cover various training window sizes, time horizons, and return thresholds.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are publicly available and included in this article.

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Accuracy

- ABC:

-

Artificial bee colony

- ANN:

-

Artificial neural network

- ARIMA:

-

Autoregressive integrated moving average

- ARMA:

-

Autoregressive moving average

- CNN:

-

Convolutional neural network

- DNN:

-

Deep neural network

- EMA:

-

Exponential moving average

- EMH:

-

Efficient market hypothesis

- FFNN:

-

Feedforward neural network

- FN:

-

Number of false negatives

- FP:

-

Number of false positives

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithms

- GBT:

-

Gradient boosted trees

- LOG:

-

Logistic regression classifier

- LSTM:

-

Long short term memory

- ML:

-

Machine learning

- NSE:

-

National stock exchange

- P:

-

Precision

- PRE:

-

Prediction rule ensembles

- PSVM:

-

Proximal support vector machine

- R:

-

Recall

- RBF:

-

Radial basis function

- RC:

-

Random choice

- RF:

-

Random forest

- ROA:

-

Return on assets

- RSI:

-

Relative strength index

- SVM:

-

Support vector machine

- TN:

-

Number of true negatives

- TP:

-

Number of true positives

References

Aasi B, Imtiaz SA, Qadeer HA, Singarajah M, Kashef R (2021) Stock price prediction using a multivariate multistep LSTM: a sentiment and public engagement analysis model. In: IEMTRONICS, pp 1–8

Al Wadi S, Almasarweh M, Alsaraireh AA (2018) Predicting closed price time series data using ARIMA model. Mod Appl Sci 12(11):181–185

Aloraini A (2015) Penalized ensemble feature selection methods for hidden associations in time series environments case study: equities companies in Saudi stock exchange market. Evol Syst 6:93–100

Al-Shamery E, Al-Shamery AA (2018) Enhancing prediction of NASDAQ stock market based on technical indicators. J Eng Appl Sci 13:4630–4636

Ampomah EK, Qin Z, Nyame G (2020) Evaluation of tree-based ensemble machine learning models in predicting stock price direction of movement. Information 11:332

Basak S, Kar S, Saha S, Khaidem L (2019) Predicting the direction of stock market prices using tree-based classifiers. N Am J Econ Finance 47:552–567

Breiman L (2001) Random forests. Mach Learn 45:5–32

Chandar SK (2022) Convolutional neural network for stock trading using technical indicators. Autom Softw Eng 29:1–14

Chen Y, Hao Y (2017) A feature weighted support vector machine and K-nearest neighbor algorithm for stock market indices prediction. Expert Syst Appl 80:340–355

Chen YJ, Chen YM, Lu CL (2017) Enhancement of stock market forecasting using an improved fundamental analysis-based approach. Soft Comput 21:3735–3757

Chen C, Chen C, Liu T (2020) Investment performance of machine learning: analysis of S&P 500 index. Int J Econ Financ Issues 10:59–66

Chen Y, Wu J, Wu Z (2022) China’s commercial bank stock price prediction using a novel K-means-LSTM hybrid approach. Expert Syst Appl 202:117370

Chong E, Han C, Park FC (2017) Deep learning networks for stock market analysis and prediction: methodology, data representations, and case studies. Expert Syst Appl 83:187–205

Dai Z, Dong X, Kang J, Hong L (2020) Forecasting stock market returns: new technical indicators and two-step economic constraint method. N Am J Econ Finance 53:101216

Fama EF (1995) Random walks in stock market prices. J Financ Anal 51(1):75–80

Fischer T, Krauss C (2018) Deep learning with long short-term memory networks for financial market predictions. Eur J Oper Res 270:654–669

Gaspareniene L, Remeikiene R, Sosidko A, Vebraite V (2021) Modelling of S&P 500 index price based on U.S. economic indicators: machine learning approach. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Eng Econ 32:362–375

Henrique BM, Sobreiro VA, Kimura H (2018) Stock price prediction using support vector regression on daily and up to the minute prices. J Finance Data Sci 4:183–201

Heo J, Yang JY (2016) Stock price prediction based on financial statements using SVM. J Hybrid Inf Technol 9(2):57–66

Hong**ng Y, Naveed HM, Answer MU, Memon BA, Akhtar M (2022) Evaluation optimal prediction performance of MLMs on high-volatile financial market data. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 13

Jarrett JE, Schilling J (2008) Daily variation and predicting stock market returns for the frankfurter borse (stock market). J Bus Econ Manag 9:189–198

Kou G, Xu Y, Peng Y, Shen F, Chen Y, Chang K, Kou S (2021) Bankruptcy prediction for SMEs using transactional data and two-stage multiobjective feature selection. Decis Support Syst 140:113429

Krauss C, Do XA, Huck N (2017) Deep neural networks, gradient-boosted trees, random forests: statistical arbitrage on the S&P 500. Eur J Oper Res 259:689–702

Kumar D, Meghwani SS, Thakur M (2016) Proximal support vector machine based hybrid prediction models for trend forecasting in financial markets. J Comput Sci 17:1–13

Kumar R, Kumar P, Kumar Y (2022) Multi-step time series analysis and forecasting strategy using ARIMA and evolutionary algorithms. Int J Inf Technol 14:359–373

Labiad B, Berrado A, Benabbou L (2016) Machine learning techniques for short term stock movements classification for moroccan stock exchange. In: 11th SITA, Mohammedia, Morocco, 2016

Li G, Zhang A, Zhang Q, Wu D, Zhan C (2022) Pearson correlation coefficient-based performance enhancement of broad learning system for stock price prediction. IEEE Trans Circuits Syst II 69:2413–2417

Lin Q (2018) Technical analysis and stock return predictability: an aligned approach. J Financ Mark 38:103–123

Liu Q, Tao Z, Tse Y, Wang C (2022) Stock market prediction with deep learning: the case of China. Finance Res Lett 46:102209

Lv P, Wu Q, Xu J, Shu Y (2022) Stock index prediction based on time series decomposition and hybrid model. Entropy 24:146

Malkiel BG (1989) Efficient market hypothesis. In: Finance. Springer, pp 127–134

Nabi RM, Ab S, Saeed M, Harron HB, Fujita H (2019) Ultimate prediction of stock market price movement. J Comput Sci 15(12):1795–1808

Nayak RK, Tripathy R, Mishra D, Burugari VK, Selvaraj P, Sethy A, Jena B (2021) Indian stock market prediction based on rough set and support vector machine approach. In: Intelligent and cloud computing, smart innovation, systems and technologies, vol 153

Nazario RTF, Silva JL, Sobreiro VA, Kimura H (2017) A literature review of technical analysis on stock markets. Q Rev Econ Finance 66:115–126

Nti K, Adekoya AF, Weyori BA (2020) Efficient stock-market prediction using ensemble support vector machine. Open Comput Sci 10(1):153–163

Patel J, Shah S, Thakkar P, Kotecha K (2015) Predicting stock and stock price index movement using trend deterministic data preparation and machine learning techniques. Expert Syst Appl 42:259–268

Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B (2011) Scikit-learn: machine learning in python. J Mach Learn Res 12:2825–2830

Picasso A, Merello S, Ma Y, Oneto L, Cambria E (2019) Technical analysis and sentiment embeddings for market trend prediction. Expert Syst Appl 135:60–70

Rana M, Uddin MM, Hoque MM (2019) Effects of activation functions and optimizers on stock price prediction using LSTM recurrent networks. In: CSAI, Bei**g, China, 2019, pp 354–358

Ruxanda G, Badea LM (2014) Configuring artificial neural networks for stock market predictions. Technol Econ Dev Econ 20:116–132

Shah D, Isah H, Zulkernine F (2019) Stock market analysis: a review and taxonomy of prediction techniques. Int J Financ Stud 7:26

Siddique M, Panda D (2019) A hybrid forecasting model for prediction of stock index of tata motors using principal component analysis, support vector regression and particle swarm optimization. I J Eng Adv Tech 9:3032–3037

Singh J, Khushi M (2021) Feature learning for stock price prediction shows a significant role of analyst rating. Appl Syst Innov 4:17

Srivinay, Manujakshi BC, Kabadi MG, Naik N (2022) A hybrid stock price prediction model based on PRE and deep neural network. Data 7, 51

TensorFlow. https://www.tensorflow.org/.

Xu Y, Kou G, Peng Y, Ding K, Ergu D, Alotaibi FS (2024) Profit- and risk-driven credit scoring under parameter uncertainty: a multiobjective approach. Omega 125:103004

Yahoo Finance. https://finance.yahoo.com/.

Yuan X, Yuan J, Jiang T, Ain QU (2020) Integrated long-term stock selection models based on feature selection and machine learning algorithms for china stock market. IEEE Access 8:22672–22685

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Groningen and Prospect Burma organization for their supports.

Funding

This research work is funded by The University of Groningen and Prospect Burma organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HH collected, generated the data, and constructed the feature vectors. HH performed formal analysis, ML methods selection, implementation of the program, training and test data selection, investigation of the results and findings. HH wrote the original draft of the work. NP defined the objective and scope of the study, gave the definitions of the feature vectors, the class labels and the random choice classifier for comparison purposes; recommended ML methods, the performance comparison method and test and the results presentation form; wrote parts of the text and acquired funding for HH; NP and MB reviewed and edited the manuscript, supervised the research work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Htun, H.H., Biehl, M. & Petkov, N. Forecasting relative returns for S&P 500 stocks using machine learning. Financ Innov 10, 118 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-024-00644-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-024-00644-0