Abstract

The study of clan paintings reveals a shift in perspective from art aesthetics to cultural connotations to cultural identity, yet literature seldom discusses the relationship between art and kinship culture. Taking the murals of ancestral hall architecture in Guangzhou as an example, this paper utilizes text mining to identify factors influencing its decorative art. It reveals the traditional rites' artistic expression through dimensions of characters' demeanor and the transmission of content values, offering a fresh perspective for heritage value research. Findings: (1) themes and implications are mostly oriented towards positive value transmission, transitioning from idealistic layman life to the realism of lower-class existence, emphasizing humanization; (2) the extroverted portrayal of characters contrasts with the dignified, restrained etiquette of traditional rites, with some characters' portrayal and facial expressions exuding approachability; (3) murals conveying positive emotions are mostly related to longevity, auspiciousness, fortune, and heroic deeds, while those conveying negative emotions mainly involve elderly male figures, reflecting a content bias related to characters; (4) historical allusion murals with complex content reduce the emotional resonance and arousal efficiency of the viewer; (5) incomplete mural content increases negative emotions in perceivers, highlighting the impact of mural preservation on emotional resonance. To delve into the formation of clan painting art, it is essential not only to interpret the diversity of its patterns but also to demonstrate the representation of its social attributes in decorative art. The formation of clan painting decorative art exhibits kinship cultural attributes, epitomizing the essence of traditional ceremonial thought.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formation of the art of painting is the result of the confluence of multicultural influences and historical contexts, reflecting humanity's pursuit of aesthetics and symbolism [1]. As interconnected pieces of art, the cultural formation of architectural mural art represents a combination of historical accumulation and artistic creation, showcasing the resonance of regional characteristics and cultural memory [2]. Serving as the spatial carriers for clan murals, the preservation of cultural heritage related to ancestral hall architecture has become a globally discussed topic, with the heritage value of ancestral hall murals elevated to the dimensions of “identity symbolism and cultural identity” [3]. The “Cultural Heritage Protection Policy” enacted by the Guangdong Provincial Government [4] emphasizes the historical value and urgency of protecting tangible heritage art, encouraging the application of scientific methods and local cultural sensitivity in restoration.

However, the pluralistic development of urban culture presents challenges of cultural loss and homogenization to ancestral hall murals: (1) a discordance between original content and modern restoration methods; (2) the potential for modern materials and techniques to conflict with the original style; (3) the possibility of historical authenticity distortion during the image restoration process. These issues stem from a lack of understanding of the cultural connotations of mural art, leading to a disconnection between protection strategies and cultural values.

The study by Guo and Singyabuth [5] focuses on Shaolin Temple murals, revealing how these works embody traditional Chinese martial arts culture and play a significant role in sha** national ideology. This art form possesses a unique power in conveying cultural values and historical context. Meanwhile, the research by Vucetic et al. [6] on Colombian mural art emphasizes the close relationship between art and politics, suggesting murals may reflect specific socio-political environments. Rolston [7] shifts focus to analyze social issues behind murals, such as inequality issues in Chile, demonstrating how murals can reflect social issues. Źrałka et al. [8] enrich this discussion further, arguing that the fictional elements in murals reflect people's aspirations for an ideal life and serve as carriers for social and cultural identity.

Li et al. [2] explore the changes in human postures in ancestral hall building murals, reflecting cultural shifts, particularly the dilution of ritual concepts and the gradual loss of traditional cultural genes. This finding suggests a transition in the cultural values and social norms reflected in the artworks. Rolston [9] focuses on the symbolic significance of murals in Northern Irish communities, especially their expression of collective memory and peace. Government demolition plans could harm this cultural memory, highlighting the importance of murals in maintaining community identity and historical continuity. Yan [10] shifts the perspective to Guangzhou ancestral hall murals, emphasizing their role as material links between the past and present, showcasing the core position of murals in transmitting and interpreting cultural values. Chen [11] reveals the clan lineage colors in ancient Chinese tomb murals through analysis, and the materials and techniques used symbolize wealth and status, highlighting the role of murals in expressing social hierarchy and clan glory.

Recent studies have primarily focused on the representation of mural art within cultural and political contexts, and how these murals reflect social and cultural identities. There has been a shift in research perspectives from art aesthetics to cultural significance and cultural identity, leading to two scholarly questions: (1) How do murals exhibit regional characteristics, historical contexts, and social changes on a local level? (2) How does mural art contribute to cultural transmission and identity formation within families and communities? Although Li et al. [2], Qi [12], and Shi and Wang [13] have explored the correlation between Chinese mural decoration and Confucian culture, they have not delved into the ritual components influencing decorative arts.

Research on the artistic elements of tangible heritage represents one of the most fundamental aspects of Chinese traditional culture and a cornerstone of national prosperity [14]. Ancestral halls, as crucial carriers of Chinese clan culture, are products of the interplay between regional culture and social history, with the mural art in Guangzhou’s ancestral halls exhibiting distinctive artistic styles and social functions [2]. According to incomplete statistics, approximately 4097 murals have been documented in Guangzhou's ancestral halls [15], with detailed descriptions provided in relevant series [16, 17], which form the foundational data for this study.

Addressing the scholarly inquiry into how kinship influences clan mural decorative art and the representation of traditional rituals in artworks, this study aims to identify the ritual factors impacting the mural art in Guangzhou’s ancestral halls. By analyzing the artistic manifestations of ritual factors through the demeanor and expressions of figures and the thematic content, this research seeks to uncover the cultural formation processes behind clan mural art. The study proposes two hypotheses: (1) Traditional rituals shape the positive thematic content and humanistic value transmission of Guangzhou’s ancestral hall murals, and their decorative art possesses both idealistic and realistic significance; (2) The demeanor and expressions of the figures in the murals reflect both material and spiritual kinship, and the overall narratives and symbolism of the murals are positive. This research provides empirical support for the application of text mining and perceptual evaluation in cultural heritage studies and incorporates traditional rituals as influential factors in the formation of clan mural art, thereby broadening the research perspective in art studies.

Although data mining aids researchers in extracting common features from 521 murals, text-based analysis may have limitations in fully elucidating the correlations between spatial functions and mural themes, content, and decorative elements. This is mainly due to the following reasons: (1) The complexity of spatial functions and artistic expressions. Due to policy impacts, some literature has noted the integration of lecture halls and sacrificial functions during the Ming and Qing dynasties [18], raising questions about whether mural content creation in specific cases was influenced by functional transitions; (2) The diversity of historical and cultural contexts. The changing status of Confucianism in different periods in China may influence clan culture, which could, in turn, affect the ritual components in the creation of ancestral hall mural content. For instance, during periods when Confucianism was highly esteemed, the decorative art in ancestral halls might have emphasized rituals and moral education [19], whereas in other periods, the content might lean towards everyday life or practical themes [20]. Sometimes, visual art may not fully and accurately reflect the underlying cultural meanings [21]. Ao et al. [22] highlighted this point and stressed the importance of integrating multiple perspectives and methods.

Methodology

Research framework

Figure 1 illustrates the research methodology of this paper. Stage 1 (Sect. "Introduction") involves defining the research question by understanding the history and progress of clan paintings through literature review, identifying research gaps to specify research objectives and hypotheses, thereby positioning the study's academic value within the field. Stage 2 (Sect. "Data sources") focuses on extracting, categorizing, and coding textual materials and deriving influencing factors on the formation of clan painting art through descriptive statistics of adjectives and emotional words. Stage 3 (Sect. "Constructing evaluation scales") utilizes the co-occurrence network generated from coded groups to reveal potential interrelations between cluster groups and their elements, refining ‘posture and expressions' and 'character coloring' as two core themes. Stage 4 (Sect. "Results") centers on the analysis and evaluation of clan painting art. It discusses how kinship relationships shape clan painting art and how these two core themes are expressed by analyzing typical painting samples. Additionally, it employs the Semantic Differential Method and factor analysis for perceptual evaluation of Mural Content to validate the results of emotional analysis. Stage 5 (Sect. "Discussions") discusses the results and introduces new academic questions. This stage responds to the research questions, hypotheses, and inferences made in the introduction, compares findings with those of peers, and identifies unresolved issues. It also discusses the potential and technical challenges of applying text mining in the art field and creates an academic contribution map to highlight the study's value. Lastly, it acknowledges limitations and suggests improvements.

The data processing procedure in Stages 2–3 includes [23, 24]: (1) selecting appropriate textual materials, summarizing them in Excel in the form of excerpted sentences, and categorizing and coding these cells for theme analysis; (2) during data cleaning, writing “Force Pick up” and “Force Ignore” scripts to extract compound words and filter out meaningless words, checking for expanded words, and handling singular and plural words in the frequency list; (3) conducting co-occurrence networks analysis based on grouped coded variables. High co-occurrence words in the compiled database are displayed in a network graph, analyzing patterns and similarities between words for theme mining. The thickness of the connecting lines indicates the degree of relevance, numbers represent co-occurrence frequency, and the size of word circles indicates frequency, with nodes having multiple branches typically being thematic due to their centrality.

Data sources

Chinese scholar Liu’s “Guangzhou Ancestral Hall Murals”, volumes one and two, published in 2015, is where the research material for this study came from [16, 17]. These two books were originally intended as a methodical way to go through and examine the distinctive mural painting that may be found in ancestral halls around Guangzhou. Murals are a type of art that is both unique and prone to deterioration, so it is important to preserve and share them through publications like books. The 521 artistically valuable ancestral hall murals were painstakingly arranged by Liu with the goals of cultural preservation, scholarly investigation, and educational popularization. Using a combination of text and imagery, he cataloged the murals’ origins, content, artistic techniques, and qualities, along with their connections to the ancestral halls in which they are located.

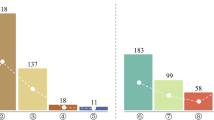

To focus on the theme, only descriptive details about the paintings will be taken out and analyzed. Textual analysis will not consider details from the books, including images, authors, inscription dates, painting names, ancestral hall locations, and scroll specs. This data has been collated by the team into an Excel document that has 521 groups of cell text prior to extraction for analysis. In addition, new list columns were established by information filtering and the mural subjects and tale contents were split into external variables Group A and Group B in preparation for the subsequent coding investigation. The initial subject and material categorization is listed in Table 1. Figure 2 illustrates the number of murals in groups A and B following classification, highlighting the process’s objectivity.

Constructing evaluation scales

The factors affecting an individual’s perception of a material form are complex and include a variety of aspects such as its substance itself, individual experience, environmental factors, non-environmental factors, and sensory abilities [25]. To assess the authenticity of the value transmission in mural content, this paper employs the Semantic Differential Method (SD), factor analysis, and cluster analysis to evaluate murals from the perspectives of emotional perception and value dimensions. The SD method, also known as the sensory recording method, proposed by Osgood [26], is a psychometric technique for assessing participants’ psychological reactions to verbal scales. Utilizing Stratified Sampling Method, this study selects 25 murals with varying themes from a pool of 318 for perceptual evaluation surveys. The evaluation dimensions are built upon the Affective Arousal Theory, which is grounded in cognitive psychology principles and explores the interaction between environmental stimuli and individual emotional states [27]. This theory introduces a multidimensional measurement tool named the Environmental Emotional Response Index (EERI), aimed at quantitatively analyzing the impact of the environment on human emotions. EERI assesses the environment on two main dimensions, pleasure and arousal, measuring both the positivity/negativity of emotions triggered and the level of mental activation. The constructed evaluation scale includes ten pairs of adjectives, six derived from the Affective Arousal Model (happy-unhappy-1, excited-calm-2, relaxed-tense-3, interested-monotonous-4, inspiring-depressed-5, arousing-tedious-6), three from the aesthetic senses of murals (comfortable-uncomfortable-7, warm-desolate-8, harmonious-inharmonious-9), and one pair from the content and value aspect, emphasizing the pursuit of basic material desires versus the aspiration for spiritual ideals such as simplicity, immortality, prosperity, and peace (Materialistic-Spiritual-10). These 10 sets of adjectives were coded using numbers from 1 to 10 to facilitate subsequent analysis.

The assessment is broken down into five indicators, each of which has a separate score: neutral-3, comparably closer to negative adjectives-2, near to negative adjectives-1, neutral-5, and comparatively closer to positive adjectives-4. The evaluative representation of the mural contents is shown in Table 2.

Results

Co-occurrence network based on coded B groups

KH Coder is an AI-based text analysis tool that facilitates discourse analysis by employing artificial intelligence algorithms [28]. Using KH Coder, this study created “co-occurrence” networks for two groups of coded content, comprising “nodes” and the “edges” that connect these nodes. In this network, nodes connected by edges share close relationships, with an increase in edges indicating higher relevance. The Reading Value (RV) at each node is generated based on textual semantics, with the software classifying words into clusters of different colors based on RV and textual relevance. This study extracted words with the Top 100 Term Frequency (TF) for display and outputted the minimum spanning trees (Figs. 3, 4).

Figure 3 illustrates the thematic network formed by Group A’s coding, with thematic clusters differentiated by dashed lines. The central cluster is formed around “Character” and “Floral Plant,” with “Bird and Beast” and “Portfolio Pictures” forming secondary clusters. Due to a lower number of Top 100 vocabulary in the “Scenery” cluster, its core content is not prominently represented, leading to its classification as an ineffective cluster. The connection between “Character” and “Floral Plant” clusters through “Murals” suggests a symbiotic relationship between the two clusters, inferring that floral plants are a primary element in ancestral hall mural decoration [29]. Additionally, the link between “Floral Plant” and "Bird and Beast" clusters through the word “Symbol” and the internal vocabulary of both clusters, such as “Longevity Stone,” “Peony,” “Magpie,” “Fairy Crane,” “Pine,” etc., suggests that floral plants and birds and beasts primarily serve metaphorical and symbolic roles in mural decoration [30]. They collectively underscore the profound implications of the story content, employing the technique of metaphorical representation (highlighted in green vocabulary). The accompanying vocabulary between “Floral Plant” and “Portfolio Pictures” clusters, including words like “happiness,” “beauty,” “wealth,” “couple,” “longevity,” etc., underscores that elements composing mural compositions typically carry consistent implications [31], reflecting a specific societal aspiration for a desirable life.

Figure 4 presents a thematic network based on coding group B. The term “Depiction” serves as a link between the themes “Legendary Story” and “Aspiring Life,” grou** them into clusters while illustrating their separation and symbiotic relationship. Hence, it can be inferred that ancestral hall murals express a beautiful aspiration towards life through the depiction of life stories [32]. Dark green terms highlight the figurative elements referenced in the murals, such as well-known figures like “Lv Dongbin (吕洞宾, RV = 12),” “Zhang Guolao (张果老, RV = 13),” “** mechanisms have led to the expansion of this field into semiotics, sociology, and phenomenology [46], Zhou and Taylor [47], Huang [48] seems to indicate a divergence between the color scheme of Guangzhou ancestral hall murals and the color system advocated in ancient Chinese folklore, leading to further intriguing questions: (1)What are the differences between the Guangzhou ancestral hall murals and the ancient Chinese folk color system; (2) Were the backgrounds and colors used for the figures in the Canton ancestral hall murals influenced by kinship culture? If so, in what ways.

A questionnaire survey involving 24 experts and encompassing 10 evaluation criteria (producing 240 data points per sample) was conducted. This implies that a dataset comprising 76,320 data points will be generated from the 318 mural samples, highlighting the importance of using sampling methods to reduce data processing load, improve analytical efficiency and quality, and ensure the scientific rigor and feasibility of the study [49]. Both random sampling and subjective selection have their respective advantages and disadvantages in statistical methodology. Complete random sampling may result in uneven sample coverage [50], while subjective selection might introduce selection bias [51]. As a compromise, this study employed stratified sampling during the questionnaire design phase, selecting 25 mural samples for perceptual evaluation (totaling 6,000 data points).

The detailed sampling process provides a scientific basis for the results: (1) The 318 murals were categorized into five distinct themes based on imagery and descriptive content (first-level stratification); (2) Further stratification was based on story content (teaching, inspiration, seeking blessings, labor, reunion), decorative elements (mountains, rocks, plants, animals, furniture, books, figures), artists, color schemes, type of ancestral hall (public, family, clan), scale (large, medium, small), and the mural's placement within the hall (lintel, corridor, main hall, central hall); (3) An equal number of samples (5) were drawn from each stratum, ensuring that the selected samples represented the diversity, richness, uniqueness, and variety of the themes. Second, while questionnaire analysis based on a small sample size may have certain limitations [52], the combined use of the SD method, factor analysis, and cluster analysis helps mitigate these limitations and provides persuasive evidence for the validity of small-sample analysis [53]. Additionally, the 24 expert evaluators come from diverse fields within the arts and humanities, ensuring that the evaluation reflects a broad spectrum of perspectives.

Despite providing a rationale for the stratified sampling and combined analytical methods, it must be acknowledged that increasing and diversifying the sample size will enhance the quality of analysis. Increasing the sample size within each secondary stratum will improve the reliability of statistical analysis [54] and enable a more comprehensive explanation of the complexity of mural art. Furthermore, the scope of this work is limited by sample coverage. A total of 269 murals (51.6%) were placed at the entrances of ancestral halls, while the rest were located in worship halls and back halls. The content of the murals often correlates with their placement and spatial function, and the unequal sample coverage may introduce partial bias into the study results.

Recommendations for improvement: (1) Develo** systematic stratified sampling standards, refining sampling methods, and ensuring the typicality and representativeness of selected samples; (2) Increasing the sample size within each secondary stratum to enhance the representativeness and reliability of statistical analysis; (3) Ensuring balanced coverage of murals from different decorative locations and spatial functions to reduce sample bias. Future experiments will consider these aspects in detail.

Conclusions

Findings: (1) the themes and implications of ancestral hall murals in Guangzhou are predominantly oriented towards positive and proactive value transmission. The content transitions from focusing on idealistic hermit life to realistic depictions of the lower strata of society, emphasizing human-centric values; (2) murals conveying positive emotions are mostly named after themes of longevity, auspiciousness, prosperity, and heroic deeds. In contrast, those depicting negative emotions primarily involve elderly male figures, reflecting a content preference related to character depiction; (3) murals with historical allusions have relatively complex content, which diminishes emotional resonance and arousal efficiency among viewers; (4) the content of incomplete murals increases negative emotions in perceivers, highlighting the impact of the preservation state of murals on emotional resonance; (5) murals with materialistic themes are usually related to wealth and are consistent with the results of factor analysis, reflecting the alignment between mural content, implications, and emotional responses; (6) some murals feature extroverted character images that contrast with the dignified and restrained etiquette of traditional rites. Meanwhile, the portrayal and facial expressions of certain characters demonstrate approachability, contrasting with traditional decorum.

As artworks imbued with clan hues, the development of clan painting and decorative arts exhibits kinship cultural attributes and is a concentrated expression of traditional ritualistic thought. The application of text mining and perceptual evaluation to heritage value research holds potential, and this paper provides empirical support. Future research by the team will focus on the relationship between the color palette of clan paintings and traditional color systems.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The data underlying the research for this paper can be found in the appendix 'Sample data.'

References

Rudd A. Painting and presence: why paintings matter. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192856289.001.0001.

Li W, Lv H, Liu Y, Chen S, Shi W. An investigating on the ritual elements influencing factor of decorative art: based on Guangdong’s ancestral hall architectural murals text mining. Herit Sci. 2023;11(1):234. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01069-1.

Carroll CL. 3 The Transculturation of Exile: Visual Style and Identity in the Frescoes of the Aula Maxima at St. Isidore’s (1672). In Exiles in a Global City 2018 (pp. 89–143). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004335172_005

Wu Z, Ma J, Zhang H. Spatial reconstruction and cultural practice of linear cultural heritage: a case study of Meiguan Historical Trail, Guangdong, China. Buildings. 2022;13(1):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13010105.

Guo X, Singyabuth S. Kung Fu Mural Painting at Shaolin Temple, Henan: Chinese traditional fighting culture in the context of pre-modern nation state (Doctoral dissertation, Mahasarakham University). 2022. http://202.28.34.124/dspace/handle123456789/1813

Vucetic S, Ranogajec J, Vujovic S, Pasalic S, van der Bergh JM, Miljevic B. Fresco paintings deterioration: case study of Bodjani monastery. Serbia Microscopy Microanal. 2018;24(S1):2166–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1431927618011315.

Rolston B. ¡ Hasta la victoria!: Murals and resistance in Santiago. Chile Identities. 2011;18(2):113–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289x.2011.609437.

Źrałka J, Radnicka K, Banach M, Ramírez LA, de Ágredos-Pascual ML, Vidal-Lorenzo C, Frühsorge L, Velásquez JL. The Maya wall paintings from Chajul Guatemala. Antiquity. 2020;94(375):760–79.

Rolston B. ‘Trying to reach the future through the past’: Murals and memory in Northern Ireland. Crime Media Cult. 2010;6(3):285–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659010382335.

Yan J. Characteristics of the carving and mural art of the Chen’s academy in Guangzhou. Art J. 2016;3:117–22.

Chen P. Who's Agency? A Study of Burial Murals in Ancient China. The Ethnograph: Journal of Anthropological Studies. 2023;7(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.14288/ejas.v7i1.198300

Qi J. The Functions of Modern Mural Art. Cross-cultural communication. 2017;10(2):25 (in Chinese). https://wwwv3.cqvip.com/doc/journal/937088930

Shi Y, Wang X. A spatial study of the relics of Chinese tomb murals. Religions. 2023;14(2):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14020166.

Liu Z, Chang JA. When the whole-nation system meets cultural heritage in China. Int J Cult Policy. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2023.2249488.

Hu X. Guangzhou traditional architectural mural 'Fisherman, Woodcutter and Cultivator'. China Heritage Journal. 2021:(008):1–2 (in Chinese). https://wwwv3.cqvip.com/doc/newspaper/2885146386

Liu Z. Guangzhou ancestral hall murals-top. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Publishing House; 2015 (in Chinese). https://book.kongfz.com/203004/6266374090

Liu Z. Guangzhou ancestral hall murals-next. Guangzhou: Guangzhou Publishing House; 2016 (in Chinese). https://book.kongfz.com/673986/6933624607

Li W, Gao X, Du Z, Chen S, Zhao M. The correlation between the architectural and cultural origins of the academies and the ancestral halls in Guangdong, China, from the perspective of kinship politics. J Asian Architect Building Eng. 2023: https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2278451

Zhang Y, Li W, Cai X. A cultural geography study of the spatial art and cultural features of the interior of Lingnan ancestral halls in the Ming and Qing dynasties. J Asian Architect Build Eng. 2023;22(6):3128–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2215846.

Charak SD, Billawaria AK. Pahāṛi Styles of Indian Murals. Abhinav Publications; 1998. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130000795114085376

Ao J, Xu Z, Li W, Ji S, Qiu R. Quantitative typological analysis applied to the morphology of export mugs and their social factors in the Ming and Qing dynasties from the perspective of East-West trade. Herit Sci. 2024;12(1):125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01237-x.

Ao J, Ye Z, Li W, Ji S. Impressions of Guangzhou city in Qing dynasty export paintings in the context of trade economy: a color analysis of paintings based on k-means clustering algorithm. Herit Sci. 2024;12(1):77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01195-4.

Higuchi K. A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using Anne of green gables (Part I). Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Rev. 2016;52:77–91.

Higuchi K. A two-step approach to quantitative content analysis: KH coder tutorial using Anne of Green Gables (part II). Ritsumeikan Soc Sci Rev. 2017;53(1):137.

Li W, Liu Y, Lv H, Ma Y, Shi W, Qian Y. Using graphic psychology and spatial design to intervene in balance coordination in patients with balance disorders. J Asian Architect Build Eng. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2300395.

Osgood CE, Suci GJ, Tannenbaum PH. The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois press; 1957. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1958-01561-000

Russell JA, Lanius UF. Adaptation level and the affective appraisal of environments. J Environ Psychol. 1984;4(2):119–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(84)80029-8.

Ylijoki O, Porras J. Conceptualizing big data: analysis of case studies. Intell Syst Accounting Fin Manag. 2016;23(4):295–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/isaf.1393.

Liu G. Creation of flora and fauna and bird and flower paintings in Shanxi temple murals. Art Observ. 2020;02:138–9.

Cao K. Multifaceted integration: rethinking the Tang dynasty tomb mural painting of “gold basin flowers and birds.” Image Historiograph. 2021;02:175–91.

Yu M, Tao Y, Tian W. The Diversity of Mural Painting from the Perspective of Architectural Properties. Art Magazine. 1984:(08):8–11+34 (in Chinese). https://wwwv3.cqvip.com/doc/journal/917832132

Liu T. Study on the Auspicious Allegory of Mural Paintings in Song Dynasty Tombs in Henan Province (Master dissertation, Henan University) (in Chinese). 2013. https://wwwv3.cqvip.com/doc/degree/1870947415

Feng X. On the materia medica and origin of the “trees and figures” theme in tang tomb screen mural paintings. Soc Sci Ningxia. 2015;6:162–7.

Ao J, Li W, Ji S, Chen S. Maritime silk road heritage: quantitative typological analysis of qing dynasty export porcelain bowls from Guangzhou from the perspective of social factors. Heritage Science. 2023;11(1):263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-023-01103-2.

Dragostinov Y, Harðardóttir D, McKenna PE, Robb DA, Nesset B, Ahmad MI, Romeo M, Lim MY, Yu C, Jang Y, Diab M. Preliminary psychometric scale development using the mixed methods Delphi technique. Methods in Psychology. 2022;7: 100103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metip.2022.100103.

Friborg O, Martinussen M, Rosenvinge JH. Likert-based vs. semantic differential-based scorings of positive psychological constructs: A psychometric comparison of two versions of a scale measuring resilience. Personal Individ Differ. 2006;40(5):873–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.08.015.

Bell-Villada GH. Art for art's sake & literary life: how politics and markets helped shape the ideology & culture of aestheticism, 1790–1990. U of Nebraska Press; 1996. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282269556140672

Gathercole S. Art and construction in Britain in the 1950s. Art History. 2006;29(5):887–925. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2006.00527.x.

Welch SC. India: art and culture, 1300–1900. Metropolitan museum of art; 1985. https://doi.org/10.2307/606291

**e Q, Hu L, Wu J, Shan Q, Li W, Shen K. Investigating the influencing factors of the perception experience of historical commercial streets: a case study of Guangzhou’s Bei**g road pedestrian street. Buildings. 2024;14(1):138. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14010138.

Carrabine E. Picture this: criminology, image and narrative. Crime Media Cult. 2016;12(2):253–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741659016637640.

Zubieta LF. The role of rock art as a mnemonic device in the memorisation of cultural knowledge. InRock art and memory in the transmission of cultural knowledge 2022 (pp. 77–98). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96942-4_4

Douglass A, Badham M. Aesthetic systems of participatory painting: playing with paint, dialogic art, and the innovative collective. Public Art Dialogue. 2022;12(1):52–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/21502552.2022.2033916.

Arroyo-Lemus EM. The survival of Maya blue in sixteenth-century Mexican colonial mural paintings. Stud Conserv. 2022;67(7):445–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2021.1913825.

Chicoine D. Enchantment in ancient Peru: Salinar period murals and architecture. World Art. 2022;12(1):67–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2021.1999315.

Su M, Li S, Lu Y, Yang L, Duan Y, ** a digital archive system for imperial Chinese robe in the Qing dynasty. Front Neurosci. 2022;16: 971169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2022.971169.

Zhou J, Taylor G. The language of color in China. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2019. https://www.cambridgescholars.com/product/978-1-5275-1122-4

Huang X. A study of dress culture in guangfu export paintings (master dissertation, bei**g institute of fashion technology). 2021 (in Chinese). https://wwwv3.cqvip.com/doc/degree/2418009909

Zickar MJ, Keith MG. Innovations in sampling: Improving the appropriateness and quality of samples in organizational research. Annu Rev Organ Psych Organ Behav. 2023;10:315–37. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-052946.

Singh G, Chouhan R, Singh J, Kaur N, Mamta M. Prominent sampling techniques analysis in machine learning: bibliometric survey and performance evaluation. In 2022 Seventh International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Grid Computing (PDGC) 2022 (pp. 131–137). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/PDGC56933.2022.10053294

Revilla M, Ochoa C. Alternative methods for selecting web survey samples. Int J Mark Res. 2018;60(4):352–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785318765537.

Chandrasekharan S, Sreedharan J, Gopakumar A. Statistical issues in small and large sample: need of optimum upper bound for the sample size. Int J Comput Theor Stat. 2019;1:1.

Popat SK, Emmanuel M. Review and comparative study of clustering techniques. Int J Comput Sci Inf Technol. 2014;5(1):805–12.

Bujang MA, Sa’at N, Bakar TM. Determination of minimum sample size requirement for multiple linear regression and analysis of covariance based on experimental and non-experimental studies. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.2427/12117.

Acknowledgements

This study acknowledges the time and contributions of 24 experts who gave and contributed to the perceptual assessment of the mural samples.

Funding

This study is funded by the 2022 Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Lingnan Culture Project, titled 'A Study on the Architectural and Cultural Heritage of Cantonese Merchants in Lingnan (Grant No. GD22LN06)'; 2023 Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics Dongfang College Key Institute-Level Project (Grant No. 2023dfyz005); 2023 Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics Dongfang College, College-level Ideological and Political Education Teaching Research Project, entitled ‘Research on Design Education Practice under the Guidance of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty Values (Grant No. 23JK22); Guangzhou Huashang College Research Department (Grant No. 2018HSDS10 and 2019HSXS03); Guangdong Province Education Science Planning Project (Grant No. 2023GXJK612). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L., J.A., W.S., Y.L. and Y.C.; methodology, W.L. and W.S.; software, W.L., S.M. and W.S.; validation, W.L. and W.S.; formal analysis, W.L. and W.S.; investigation, H.L., S.M., Y.L. and J.A.; resources, H.L., Y.L. and S.M.; data curation, W.L. and W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.L. and W.S.; writing—review and editing, W.L. and W.S.; visualization, W.L. and W.S.; supervision, W.L. and W.S.; project administration, W.L. and W.S.; funding acquisition, W.S., J.A. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been ethically approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Science and Technology Management at Zhejiang University of Finance and Economics Dongfang College (No. DFL20231230004), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Ma, S., Shi, W. et al. Artistic heritage conservation: the relevance and cultural value of Guangzhou clan building paintings to traditional rituals from a kinship perspective through perceptual assessment and data mining. Herit Sci 12, 216 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01328-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40494-024-01328-9