Abstract

Background

One of the most important considerations for acoustic telemetry study designs is detection probability between the transmitter and the receiver. Variation in environmental (i.e., wind and flow) and abiotic (i.e., bathymetry) conditions among aquatic systems can lead to differences in detection probability temporally or between systems. In this study we evaluate the effect of distance, receiver mount design, transmitter depth, and wind speed on detection probabilities of two models of acoustic transmitters in a mid-sized river. InnovaSea V16-6H (hereafter V16) and V13-1L (hereafter V13) tags were deployed in the James River, SD at 0.36 m (deep) and 2.29 m (V16 tag) or 1.98 m (V13 tag; shallow) above the benthic surface downstream of InnovaSea VR2W stationary receivers at distances of 100, 200, or 300 m. We used two receiver mount designs that included a fixed position within a PVC pipe on the downstream side of a bridge piling or a metal frame deployed in the middle of the river channel. Tags were deployed for 72 h at each location, and hourly detections were summarized. We evaluated downstream distance, receiver mount design, tag depth, and wind effects on tag detection using Bayesian logistic regression.

Results

Detection probability decreased as distance increased for all combinations of tag types and mount designs and varied from nearly 100% at 100 m to less than 10% at 300 m. The V16 transmitter had greater detection probability by the receiver mounted in the pipe than in the midriver frame. For both mounts, the deep V16 transmitter had greater detection probability than the V16 shallow transmitter. Detection probability of the V13 transmitter was similar between receiver mounts or transmitter depths. Wind speed had a negative impact on detection probabilities of both transmitter types and depths, except the deep V16 transmitter.

Conclusions

Deploying acoustic receivers in PVC pipes rather than midriver frames provided greater downstream detection probabilities for V16 transmitters under conditions evaluated in this study. In addition, V16 transmitters had greater detection probabilities when positioned deep within the water column rather than near the surface. We also demonstrated that wind speed can have a negative impact on detection probabilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Understanding spatial ecology and behavior of fishes in freshwater and marine environments has long been an area of focus for fisheries biologists. With the advancement of acoustic telemetry technology, researchers are now able to answer a host of questions that would otherwise have been unachievable [1]. There has been a recent increase in the number of acoustic telemetry studies largely due to the increased tag life, transmitting power, and reliability in acoustic equipment available to researchers [2]. Passive telemetry data can be collected continuously throughout the life of an acoustic tag and reduces the labor needed to identify fish locations [3, 4]. Acoustic telemetry has been used to collect a wide variety of ecological information on fish, such as home range size [5], spawning migrations [6, 7], annual survival [8], or interactions with man-made structures [9].

While acoustic telemetry has numerous applications for monitoring fish behavior, there are important considerations when selecting and deploying specific acoustic telemetry equipment. One of the most important considerations is the probability of the transmitter being detected by a receiver [10]. There are numerous factors that can influence tag detection probability including tag power, line of sight limitations between the transmitter and receiver (e.g., bathymetry, sinuosity, bridge pilings), temperature, signal rebounds, tag signal collisions, suspended particles in the water column, and interference via wind and boat noise [11,12,13], and these factors can differ across waterbodies [14]. In addition, conditions within the study system often dictate which mount design can be deployed at a specific site. Often, multiple receiver mount designs and deployment locations are required within the same study to account for different habitat and environmental conditions [15, 16]. Bridge-mounted PVC pipe mount systems and metal frame mount designs are both commonly used for telemetry studies in riverine systems with soft substrates and high flows [17, 18]. Understanding the factors affecting detection probabilities in the study area is vital to selecting the best tag type and power, appropriately deploying receiver arrays, and interpreting detection data.

Most freshwater acoustic telemetry range testing studies conducted have been in open water lentic environments, where receiver grids are used to constantly monitor fish locations in the waterbody [19,20,21]. Range testing studies in lotic systems are sparse, and most range tests were conducted to evaluate the effects of a single factor limiting detections, primarily maximum detection distance [22,23,24]. However, Abeln [25] indicated that maximum detection distance alone is not enough to understand detection probability and other environmental factors may be important to consider. Lotic systems present unique factors that can limit detections such as sinuosity, sediment load, current velocity, and moving debris such as woody structures [26,27,28,29]. In addition, habitat use by fish can influence tag detection probability, particularly within structure [15] and varying depths in the water column [30]. Develo** a better understanding of detection probability under varying conditions in lotic systems could inform species and project-specific study design.

Multiple studies monitoring fish movement have been implemented in lotic systems across North America [18, 31, 32]. However, there is a lack of data on the detection probability of acoustic telemetry systems in lotic systems, such as the Missouri River and its tributaries. Acoustic telemetry range test studies in the Missouri River and its tributaries have been limited to evaluating the effect of distance on detection ranges of transmitters [18]. Given the collaborative nature of acoustic telemetry passive receiver arrays in large, connected systems [33, 34], develo** an understanding of factors influencing detection probabilities in these smaller tributary systems would likely provide insight into maximizing detection probabilities with optimal receiver deployment techniques and transmitter types. Recently in South Dakota, several telemetry projects have been implemented by various universities and state and federal agencies to describe movement trends of various fish species as they move among the Missouri River and its three eastern South Dakota tributaries: Big Sioux, Vermillion, and James rivers. To better understand the performance of passive acoustic telemetry in a tributary system, our objectives were to evaluate the detection probabilities of two acoustic tag models: (1) at various downstream distances from the receiver, (2) for two different receiver mount designs, (3) at two different tag depths, (4) across varying wind speeds.

Methods

Study site

The James River is the largest tributary to the Missouri River in eastern North Dakota and South Dakota. The river originates in central North Dakota and flows approximately 1202 river kilometers (rkm) through glaciated drift prairie to its confluence with the Missouri River near Yankton, South Dakota.

Receiver and tag deployment

We deployed two VR2W (InnovaSea) acoustic receivers on the downstream side of a bridge piling in the James River at 207 river kilometers upstream of its confluence with the Missouri River near Michell, South Dakota (SD) (43.643426, − 97.886842). One receiver was deployed within a 3.05-m long, 0.10-m diameter polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe on the downstream side of the bridge piling to avoid potential damage from floating debris. The PVC pipe was deployed with the bottom of the pipe approximately 18 cm above the benthic surface of the river and was secured to the bridge using two metal bands and a ratchet strap (Fig. 1). The receiver was lowered into the PVC pipe using 3.2-mm galvanized steel cable until the acoustic receiver’s hydrophone was sticking approximately 4 cm out of the bottom of the PVC pipe, attached with cable to the bridge piling, and secured through a cap on top of the PVC pipe to hold it in place at the correct depth. The hydrophone was positioned at a depth of 3.05 m from the surface of the water at the start of the study. The second receiver was deployed at the bottom of the river in a metal frame mount with the receiver bolted into a metal cylinder with the hydrophone facing up (hereafter referred to as frame mount). We secured the second receiver to the upstream bridge piling so it would be in line with the pipe mount using galvanized steel cable and anchored it with a concrete block attached to 2 m of cable on the downstream side (Fig. 2). The receivers placed into the PVC pipe and metal frame are hereafter referred to as the pipe mount and frame mount, respectively.

We used two high-power range test tags (InnovaSea V16-6H (158 dB; hereafter referred to as V16)) to assess detection probability. We tied a 28-cm long, 13-cm diameter buoy to a length of rope approximately 0.3-m longer than the depth of the river at each tag deployment location and held in location by two 4.5-kg anchors at the end of the rope. To simulate fish oriented in the middle water column and benthic surface, two tag depths were evaluated for each tag type. We tied range test tags to the rope 0.36 m (deep) and 2.29 m (shallow) above the benthic surface with a 7-cm length of #18 twisted nylon twine, and two small disc floats were used to keep the tag floating upright (Fig. 3). Assessment of detection probability for acoustic transmitters commonly positions the transmitter at the end of a rope [15, 21], but internally implanted tags may have lower detection probabilities than external tags [35]. We deployed the tags for 72 h at downstream distances of 100, 200, and 300 m downstream of the receivers. After each 72 h period, range test tags were moved to a new distance and cleaned to remove any biofouling that may have occurred. Each V16 tag emitted an acoustic signal every 180 s, and we offset the starting time for the second tag by 1 min to reduce the likelihood of tag collisions. We deployed the frame mount at a depth of 3.35 m during the V16 study. Range testing with the V16 tags occurred from July 11 to 21, 2022, and mean daily water elevation and discharge at the Mitchell, SD U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) monitoring gage station (site number 06478000) ranged from 5.3 to 5.5 m and 81.8 to 100.0 m3/s, respectively (Fig. 4).

We repeated the range testing process using one V13-1L (147 dB; hereafter referred to as V13) low-power tag. Range testing with the V13 tags occurred from August 11 to September 12, 2022. Trials initially began on July 21, but acoustic signals were disrupted during the subsequent 2 weeks of trials by a floating irrigation water pump, resulting in artificially low detection rates. Noise from human sources (such as boat motors or irrigation pumps) is a common cause of decreased detection probability [4]. We also had to repeat testing for the 100 m shallow trial and both 200 m trials due to a large tree moving directly below the receivers and interfering with signal reception. Since we only had one V13 range test tag, we were only able to test one depth at a time. We accounted for lower water elevation when choosing our shallow tag depth by tying the tag 0.36 m (deep) and 1.98 m (shallow) above the benthic surface. The V13 tag emitted an acoustic signal every 30 s. We deployed the frame mount at a depth of 2.78 m during the V13 study. All other test parameters remained the same as for the V16. Mean daily water elevation and discharge ranged from 4.5 to 5.0 m and 48.4 to 70.5 m3/s, respectively.

Data analysis

We summarized detection and wind data hourly to assess detection probability. We calculated the observed proportion of hourly detections as the number of recorded signals in an hour divided by the maximum expected number of detections (20 for V16 tags and 108 for the V13 tag). We excluded a subset of V16 hourly detection counts (n = 15) during periods when perceived tag drift, incremental changes in timing of acoustic signal transmission resulted in overlap of acoustic signals causing failure to correctly record the tag identification number. We excluded 27 h, where no detections were recorded for the V16 tag on the frame receiver at 100 m. We obtained wind data from the Iowa Environmental Mesonet and summarized mean hourly wind speed (kph) using data from the Mitchell, SD Automated Surface Observing System (ASOS). We excluded 4 h from the V16 trial and 9 h from the V13 trial when wind data were not recorded. For expected detection sample sizes across distance, receiver mount, and tag depth, see Table 1.

We evaluated the impact of distance, tag depth, wind speed, and receiver deployment design on the probability of detection for each tag type (V13 or V16) using Bayesian logistic regression. We modeled the probability of detection for each tag type using a binomial probability distribution with a logit link using the following equation:

where D is the number of detections, p is the probability of success (i.e., number of observed detections out of the total number possible within 1 h), N is the total number of possible detections in 1 h, α is the intercept, β Depth[shallow] is the slope prior for the shallow tag depth, β Receiver[pipe] is the slope prior for the pipe receiver, and βx is the slope prior for all remaining beta coefficients. We included interaction terms between distance and depth and between wind speed and depth in our model. We assumed detection probability would be nearly 1.0 at the closest distances to the receiver, that detection probability would be higher for the pipe than the frame mount based on preliminary observations, that tag depth would have no effect, and that distance and wind would have negative influences on detection probability. We ran each model using a Hamiltonian Monte Carlo algorithm with a No-U-Turn sampler, 4 Markov chains, a total of 2000 iterations per chain, and a warm-up phase of 1000 iterations. We evaluated model fits by running posterior probability checks and considered the model to have properly converged if Gelman–Rubin statistics were less than 1.1 [36]. We fit the model using rstan [37] in Program R [38] with the brms package [39]. We then ran a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of our prior selections by doubling the standard deviation values: normal(3, 1) for the intercept, Normal(0,2) for tag depth, Normal(1, 2) for the pipe mount and Normal(− 1, 1) for all remaining beta values.

Following successful model convergence, we sampled from the posterior distribution to estimate the relationship between detection probability and distance, depth, wind speed, and receiver design. When estimating detection probabilities from the posterior, we used the same downstream distances (100, 200, and 300 m), tag depths (shallow or deep), and receiver mount designs (pipe or frame) as those used during the study. We selected three wind speeds (10, 25, and 40 kph) within the range of observed values during our study period to model the impact of wind on detection probability. We summarized our posterior sampling as the mean values with 95% credible intervals for each combination of factors affecting detection.

Results

V16 trial

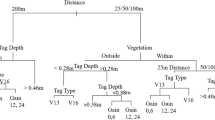

The probability of detecting V16 tags declined with increasing distance from 100 to 300 m (Fig. 5). At 100 m mean posterior estimated detection probabilities ranged from 60.5% to 96.9%. At 200 m mean posterior estimated detection probabilities ranged from 35.8% to 92.7%. At 300 m mean posterior estimated detection probabilities ranged from 16.8% to 83.9%. The variability in mean detection probability at different distances can be attributed to differences in receiver deployment method, transmitter depth, and wind speed.

Overall, detection probability was greater for the pipe mount than the frame mount during the V16 trials. Mean posterior detection probability estimates across all wind speeds and tag depths ranged from at 60.5–89.3% on the frame mount and 85.1–96.9% on the pipe mount at 100 m. At 200 m, mean posterior estimated detection probability across all wind speeds and tag depths ranged from 35.8% to 77.4% on the frame mount and 67.5–92.7% on the pipe mount (Fig. 5). The mean posterior detection probability estimates at 300 m across all wind speeds and tag depths ranged from 16.8% to 58.3% on the frame mount and from 43.0% to 83.9% on the pipe mount (Fig. 5).

Detection probability was greater for the deep tag than the shallow tag at all distances, between both mount designs, and over all wind speeds (Fig. 5). Mean posterior detection probability estimates across all wind speeds and mount designs ranged from at 86.9–96.9% on the deep tag and 60.5–92.1% on the shallow tag at 100 m, 73.1–92.7% on the deep tag and 35.8–80.9% on the shallow tag at 200 m, and 52.6–83.9% on the deep tag and 16.8–60.6% on the shallow tag at 300 m (Fig. 5).

Increasing wind speed resulted in reduced detection probability but had a greater effect on the shallow tag than the deep tag. At 100 m, the difference in posterior estimated mean detection probability declined as wind speed increased from 10 to 40 kph for the deep tag by 0.8% and 2.4% on the pipe and frame mounts and for the shallow tag by 7.0% and 15.2% on the pipe and frame mounts (Fig. 5). At 200 m, the difference in posterior estimated mean detection probability declined as wind speed increased from 10 to 40 kph for the deep tag by 1.7% and 4.3% on the pipe and frame mounts and for the shallow tag by 13.4% and 17.4% on the pipe and frame mounts (Fig. 5). At 300 m, the difference in posterior estimated mean detection probability declined as wind speed increased from 10 to 40 kph for the deep tag by 3.4% and 5.6% on the pipe and frame mounts and for the shallow tag by 17.6% and 12.3% on the pipe and frame mounts (Fig. 5).

V13 trial

The probability of detecting V13 tags declined with increasing distance from nearly 100% at 100 m to nearly 0% at 300 m (Fig. 6). Regardless of receiver mount design, wind speed, or tag depth, mean posterior estimated detection probability was > 98.9% and lower 95% credible limits exceeded 98.8% at 100 m. At 200 m, the mean posterior estimated detection probabilities were more variable but remained > 50% across all conditions. The mean posterior estimated detection probabilities at 300 m fell below 10% across all modeled receiver mount designs, wind speeds, and tag depths.

Overall detectability of the V13 tag was similar between the frame and pipe mounts at 100 and 300 m, but slightly higher for the frame mount at 200 m (Fig. 6). Mean posterior detection probability estimates of frame and pipe mounts were within 1% at 100 m. At 200 m, mean posterior estimated detection probability across all wind speeds and tag depths ranged from 70.1 − 90.4% on the frame mount and 50.7–80.5% on the pipe mount. The mean posterior detection probability estimates at 300 m across all wind speeds and tag depths ranged from 1.4% − 9.7% on the frame mount and from 0.6% − 4.5% on the pipe mount.

Detection probability was similar between tag depths at moderate wind speeds, but detection probability varied more for the deep tag (Fig. 6). Wind effect was limited at 100 and 300 m distances resulting in a lack of overall variability in detection probability. However, at 200 m, mean posterior estimated detection probability for the deep tag was slightly higher at 10 kph wind speed but lower at 40 kph compared to the shallow tag. Mean posterior estimated detection probability of the deep tag was 2.2% higher on the frame mount and 4.0% higher on the pipe mount than the shallow tag at 10 kph but was 6.4% lower on the frame mount and 8.0% lower on the pipe receiver than the shallow tag at 40 kph (Fig. 6).

Model performance

Both the V16 and V13 models performed well, and the posterior estimates predicted the observed data well. Examination of trace plots indicated good mixing of the Markov chains, all \(\hat{R}\) values were < 1.004, and effective sample sizes were large for all parameter estimates. Mean Bayesian R2 values (95% credible interval (CrI)) for the V16 and V13 models were 0.539 (0.522–0.555) and 0.944 (0.942–0.945). Posterior predictive checks, which are used to detect departures between the data and posterior estimates [40], generally replicated the shape of the data used in both models (Fig. 7). Model parameter estimates from the sensitivity analysis were all within 3.3% of the parameter estimates of the original model, and model fits were not substantially changed during the sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

An important aspect of telemetry studies in aquatic systems is to understand factors affecting tag detectability in the study system [11,12,13], including tag detection distance [10]. Often, detection distance is the primary metric assessed prior to the implementation of acoustic telemetry studies in river systems, specifically to determine whether detection distance is greater than or equal to the width of the river [18, 22, 41, 42]. We found that for both V16 and V13 tags, detectability decreased as distance downstream increased. Detection probabilities of V16 tags at 300 m was similar between our study and a recent study conducted in the Missouri River and select Missouri tributaries to the Missouri River [18]. In our study, the detection probability of V13 tags was near 0% at 300 m downstream. Similarly, the maximum detection distance of V13 tags in the Fitzroy River in Western Australia was 350 m [42]. In similar river systems with widths less than 100 m, detection probabilities are likely to remain above 60% across the width of the river channel for V13 or larger tags. If swimming speeds of the study species are considered when setting tag ** rates, detection of tags should remain greater than 60% across the river channel when width is less than 100 m [43].

The type of receiver mount design impacted tag detection probability. During the V16 trial, detection probability was higher for the receiver in the pipe mount than in the frame mount, but detection probabilities were similar for both mount designs in the V13 trial. A possible explanation for the observed difference in detection probabilities between mount types for the V16 trial but not the V13 trial is the impact of discharge. Discharge during the V16 trial was nearly double the discharge in the V13 trial. Increasing river discharge has been linked to reduced detection probability of acoustic tags [26] as a result of increased noise via turbulence and debris [14, 44]. The effect was likely higher on the frame mount, because it was deployed in the middle of the river channel, whereas the pipe mount was protected by the bridge piling. However, because we did not evaluate discharge in this study, the impact of discharge on detectability for multiple receiver mounts remains unstudied.

There are other factors influencing detection probabilities between receiver mount types to consider when deciding which type to deploy. Mounting the PVC pipe on the downstream side of a bridge piling likely reduced the impact of river conditions (i.e., discharge, debris, and turbulence) on tag detectability when compared to the frame mount. Using the PVC mount may protect the receiver from floating debris. The major drawbacks of the PVC mount design are that deployment is restricted to suitable bridge pilings (i.e., downstream detection distance and bathymetry, piling shape, water depth) and that the bridge piling blocks upstream line of sight and prevents upstream detection. The frame mount provides greater deployment flexibility than the pipe mount, because deployment is not limited to bridge pilings. However, large debris moving down river can damage or move mid-channel receiver mounts or disrupt line of sight between the transmitter and receiver resulting in decreased detections [45, 46]. It is important to note that we only assessed downstream detection probabilities for the frame mount, but detectability would likely be greater for the frame mount when not fastened to a bridge piling due to its ability to detect upstream. Other factors that could influence detection probabilities of receiver mount designs and need further evaluation include bathymetry within the detection area, sediment deposition and erosion around the receiver mount, or biofouling on the receiver [47].

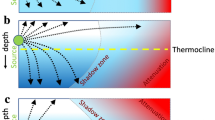

The combination of wind speed and water depth affected the V16 and V13 tags differently. Surface turbulence and wind-induced surface scattering of sound waves has been known to impact acoustic tag detectability [48]. Wind effect appeared to only impact the shallow V16 tag but impacted both the shallow and deep V13 tag. Wind induced noise may have had a greater influence on V13 tags than V16 tags due to lower power output in the V13 tags and shallower water depths. Wind-induced noise impacts a larger portion of the water column at shallower depths [30], and because the river was up to 1 m shallower during the V13 trial, the shallower depth may explain the similar effect of wind on detection probability of the deep and shallow tags. Wind-induced sound reflection from moderate winds (< 15kph) were able to reach depths of 4–5 m in Lake Skrukkebukta, Norway [49]. Due to wind-induced sound reflection impacting the water column, tag detection probabilities for pelagic fish may be more negatively impacted by wind turbulence than benthic fish. In deeper water, benthic-oriented fish may be less impacted by the effect of wind. Similarly, receivers deployed deeper in the water column are likely to be less affected by wind. However, the impact of wind on detection probability at various depths in lotic systems is not well understood.

Because V16 and V13 tags were deployed at different times under different river conditions, we did not make direct comparisons between tag types. However, detection probabilities for the V13 tag were equal or greater than the V16s at 100 and 200 m on the frame mount, which was an unexpected result. Higher tag power may result in increased detection distances [50, 51]. Higher discharge can increase static noise in the system [14] and may have caused the lower detection probabilities during the V16 trial.

Conclusions

This study provides novel information on factors that influence detection probabilities of two types of acoustic transmitters in a mid-sized river. Our results show that detection probability remained greater than 60% at 100 m for both tag types. This study also provides novel information on the differences in receiver mount design on detection probabilities of two types of acoustic transmitters. We found that detection probability was higher for the PVC pipe mount design during a period of high discharge (V16 trial) and offered more protection from debris floating downstream than the frame mount design. Therefore, when possible, we suggest using the pipe mount design over the frame mount design if there is concern about the impact of discharge or debris negatively impacting the receiver. In addition, there appeared to be a strong interaction between tag depth and wind speed when water levels were higher (V16 trial). However, wind effect was similar between the deep and shallow tags when water levels were lower (V13 trial). This study highlights the issues for further studies including the impacts of discharge, depth, and wind on detection probabilities of acoustic tags and receiver mount designs in lotic systems. Results from this study can help inform others conducting acoustic telemetry studies about factors affecting detection probability in similar mid-sized rivers.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets analyzed for the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Code used in statistical analysis available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/tanner-carlson2/Range-Test

Abbreviations

- PVC:

-

Polyvinyl chloride

- rkm:

-

River kilometer

- V16:

-

V16-6H

- V13:

-

V13-1L

- ASOS:

-

Automated surface observing system

References

Payne N, Gillanders B, Webber D, Semmens J. Interpreting diel activity patterns from acoustic telemetry: the need for controls. Mar Ecol Prog Ser. 2010;419:295–301.

Hussey NE, Kessel ST, Aarestrup K, Cooke SJ, Cowley PD, Fisk AT, Harcourt RG, Holland KN, Iverson SJ, Kocik JF, Mills-Flemming JE, Whoriskey FG. Aquatic animal telemetry: a panoramic window into the underwater world. Science. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255642.

Clements S, Jepsen D, Karnowski M, Schreck CB. Optimization of an acoustic telemetry array for detecting transmitter-implanted fish. N Am J Fish Manag. 2005;25:429–36.

Heupel MR, Semmens JM, Hobday AJ. Automated acoustic tracking of aquatic animals: scales, design, and deployment of listening station arrays. Mar Freshw Res. 2006;57:1–13.

Prechtel AR, Coulter AA, Etchison L, Jackson PR, Goforth RR. Range estimates and habitat use of invasive Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix): evidence of sedentary and mobile individuals. Hydrobiologia. 2018;805:203–18.

Aunins A, Olney JE. Migration and spawning of American Shad in the James River. Virginia Trans Am Fish Soc. 2009;138:1392–404.

Smith JA, Flower HJ, Hightower JE. Fall spawning of Atlantic Sturgeon in the Roanoke River North Carolina. Trans Am Fish Soc. 2015;144:48–54.

Colborune SF, Hayden TA, Holbrook CM, Hondorp DW, Krueger CC. Lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens) annual adult survival estimated from acoustic telemetry. J Gt Lakes Res. 2021;47:1814–23.

Coulter AA, Brey MK, Lubejko M, Kallis JL, Coulter DP, Glover DC, Whitledge GW, Garvey JE. Multistate models of bigheaded carps in the Illinois River reveal spatial dynamics of invasive species. Biol Invasions. 2018;20:3255–70.

Kessel ST, Cooke SJ, Heupel MR, Hussey NE, Simpfendorfer C, Vagle S, Fisk AT. A review of detection range testing in aquatic passive acoustic telemetry studies. Rev Fish Biol Fish. 2014;24:199–218.

Klinard NV, Halfyard EA, Matley JK, Fisk AT, Johnson TB. The influence of dynamic environmental interactions on detection efficiency of acoustic transmitters in a large, deep, freshwater lake. Anim Biotelem. 2019;7:1–17.

Krueger CC, Holbrook CM, Binder TR, Vandergoot CS, Hayden TA, Hondorp DW, Nate N, Paige K, Riley SC, Fisk AT, Cooke SJ. Acoustic telemetry observation systems: challenges encountered and overcome in the Laurentian Great Lakes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2018;75:1755–63.

Singh L, Downey NJ, Roberts MJ, Webber DM, Smale MJ, Van den Berg MA, Harding RT, Engelbrecht DC, Blows BM. Design and calibration of an acoustic telemetry system subject to upwelling events. Afr J Mar Sci. 2009;31:355–64.

Medwin H, Clay CS. Fundamentals of Oceanic Acoustics. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1997.

Selby TH, Hart KM, Fujisaki I, Smith BJ, Pollock CJ, Hillis-Starr Z, Lundgren I, Oli MK. Can you hear me now? Range-testing a submerged passive acoustic receiver array in a Caribbean coral reef habitat. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:4823–35.

Tripp SJ, Phelps QE, Hupfeld RN, Herzog DP, Ostendorf DE, Moore TL, Brooks RC, Garvey JE. Sturgeon and paddlefish migration: evidence to support the need for interjurisdictional management. Fisheries. 2019;44:183–93.

Castro-Yerty M, Bettoli PW. Range assessment and detection limitations of bridge-mounted hydroacoustic telemetry arrays in the Mississippi River. Fisheries Report 09-05, USGS Tennessee cooperative fishery research Unit and Tennessee technological University, Cookeville. 2009.

Moore MJ, Paukert CP, Brooke BL, Moore TL. Lake sturgeon seasonal movements in regulated and unregulated Missouri River tributaries. Ecohydrology. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/eco.2362.

James D, Fischer J, Laube J, Spindler M. An accuracy assessment of ultrasonic transmitter locations determined by mobile telemetry in aquatic systems. Fish Manag Ecol. 2014;21:421–5.

Hayden TA, Holbrook CM, Binder TR, Dettmers JM, Cooke SJ, Vandergoot CS, Krueger CC. Probability of acoustic transmitter detections by receiver lines in Lake Huron: results of multi-year field tests and simulations. Anim Biotelem. 2016;4:1–14.

Fincel M, Goble C, Gravenhof D, Morey H. Detection range of two acoustic transmitters in four reservoir habitat types using passive receivers. Anim Biotelem. 2022;10:1–8.

Coulter AA, Bailey EJ, Keller D, Goforth RR. Invasive Silver Carp movement patterns in the predominantly free-flowing Wabash River (Indiana, USA). Biol Invasions. 2016;18:471–85.

Dyer JJ, Brewer SK. Seasonal movements and tributary-specific fidelity of Blue Sucker Cycleptus elongatus in a Southern Plains riverscape. J Fish Biol. 2020;97:279–92.

Frechette DM, Dugdale SJ, Dodson JJ, Bergeron NE. Understanding summertime thermal refuge use by adult Atlantic salmon using remote sensing, river temperature monitoring, and acoustic telemetry. Can J Fish Aquat Sci. 2018;75:1999–2010.

Abeln JL. Environmental drivers of habitat use by bigheaded carps to inform harvest in the Starved Rock Pool of the Illinois River Master’s thesis. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University at Carbondale; 2018.

Bergé J, Capra H, Pella H, Steig T, Ovidio M, Bultel E, Lamouroux N. Probability of detection and positioning error of a hydro acoustic telemetry system in a fast-flowing river: intrinsic and environmental determinants. Fish Res. 2012;125:1–13.

Melnychuk MC. Detection efficiency in telemetry studies: definitions and evaluation methods. In: Adams NS, Beeman JW, Eiler JH, editors. Telemetry techniques: a user guide for fisheries research. Maryland: American Fisheries Society; 2012. p. 339–57.

Shroyer SM, Logsdon DE. Detection distances of selected radio and acoustic tags in Minnesota lakes and rivers. N Am J Fish Manag. 2009;29:876–84.

Winter ER, Hindes AM, Lane S, Britton JR. Detection range and efficiency of acoustic telemetry receivers in a connected wetland system. Hydrobiologia. 2021;848:1825–36.

Huveneers C, Simpfendorfer CA, Kim S, Semmens JM, Hobday AJ, Pederson H, Stieglitz T, Vallee R, Webber D, Heupel MR, Peddemors V, Harcourt RG. The influence of environmental parameters on the performance and detection range of acoustic receivers. Meth Ecol Evol. 2016;7:825–35.

Edwards ML, Balazik MT, Bangley CW, Aguilar R, Ogburn MB. Detection of a mature Atlantic sturgeon in the Patuxent River, Maryland, using passive acoustic telemetry. Northeast Nat. 2020;27:792–802.

Michel CJ, Ammann AJ, Chapman ED, Sandstrom PT, Fish HE, Thomas MJ, Singer GP, Lindley ST, Klimley AP, MacFarlane RB. The effects of environmental factors on the migratory movement patterns of Sacramento River yearling late-fall run Shinook Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha). Environ Biol Fishes. 2013;96:257–71.

Ellis RD, Flaherty-Walia KE, Collins AB, Bickford JW, Boucek R, Burnsed SLW, Lowerre-Barbieri SK. Acoustic telemetry array evolution: from species-and project-specific designs to large-scale, multispecies, cooperative networks. Fish Res. 2019;209:186–95.

Krause JR, Hightower JE, Buckel JA, Turnure JT, Grothues TM, Manderson JP, Rosendale JE, Pessutti JP. Using acoustic telemetry to estimate Weakfish survival rates along the US East Coast. Mar Coast Fish. 2020;12:241–57.

Dance MA, Moulton DL, Furey NB, Rooker JR. Does transmitter placement or species affect detection efficiency of tagged animals in biotelemetry research? Fish Res. 2016;183:80–5.

Brooks SP, Gelman A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J Comput Graph Stat. 1998;7:434–55.

Stan Development Team. RStan: the R interface to Stan. R package version. 2022;2(21):5.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R foundation for statistical computing; 2022.

Bürkner PC. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Softw. 2017;80:1–28.

Berkhof J, van Mechelen I, Hoijtink H. Posterior predictive checks: principles and discussion. Comput Stat. 2000;15:337–54.

Lubejko MV, Whitledge GW, Coulter AA, Brey MK, Oliver DC, Garvey JE. Evaluating upstream passage and timing of approach by adult bigheaded carps at a gated dam on the Illinois River. River Res Appl. 2017;33:1268–78.

Whitty JM, Morgan DL, Peverell SC, Thorburn DC, Beatty SJ. Ontogenetic depth partitioning by juvenile freshwater sawfish (Pristis microdon: Pristidae) in a riverine environment. Mar Freshw Res. 2009;60:306–16.

Starrs T, Starrs D, Lintermans M, Fulton CJ. Assessing upstream invasion risk in alien freshwater fishes based on intrinsic variations in swimming speed performance. Ecol Freshw Fish. 2017;26:75–86.

Theimer K, Lennox RJ, Haugen TO. Influence of dense macrophyte vegetation and total gas saturation on the performance of acoustic telemetry. Anim Biotelem. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-022-00275-1.

Rutz GL, Sholtis MD, Adams NS, Beeman JW. Investigation of methods for successful installation and operation of juvenile salmon acoustic telemetry system (JSATS) hydrophones in the Willamette River, Oregon, 2012. US Geol Survey Rep. 2014;1112:2014.

Titzler PS, McMichael GA, Carter JA. Autonomous acoustic receiver deployment and mooring techniques for use in large rivers and estuaries. N Am J Fish Manag. 2010;30:853–9.

Heupel MR, Reiss KL, Yeiser BG, Simpfendorfer CA. Effects of biofouling on performance of moored data logging acoustic receivers. Limnol Oceanogr-Meth. 2008;6:327–35.

Treverrow MV. Boundary scattering limitations to fish detection in shallow waters. Fish Res. 1998;35:127–35.

Gjelland KØ, Hedger RD. Environmental influence on transmitter detection probability in biotelemetry: develo** a general model of acoustic transmission. Methods Ecol Evol. 2013;4:665–74.

Babin A, Fitzpatrick L, Linnansaari T, Curry RA. Detection range of acoustic receivers in a large hydropower reservoir. Fishes. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes4040060.

Shultz A, Klimah CA, Curtis-Quick J, Claussen R, LaBine J, Ray A. Can you hear me now? Design considerations for large lake, multispecies telemetry projects. In: Bruner JC, DeBruyne RL, editors. Yellow Perch, Walleye, and Sauger: aspects of ecology, management, and culture. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 271–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jason Stahl, Nate Loecker, Jake Larsen, and Keith Schwartz for assistance with construction, deployment, and retrieval of the acoustic telemetry mounts, tags, and equipment. We would also like to thank Tony Sindt for providing a blueprint on which we based our pipe mount systems.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by State Wildlife Grant T-86-R-1 and invasive carp grant F-16-R-1. The South Dakota Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit is jointly supported by the U.S. Geological Survey, South Dakota State University, and South Dakota Department of Game, Fish and Parks.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC, BS, and LL performed field work and analyzed data. All authors read and approval in the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publications

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlson, T.L., LaBrie, L.A.P., Wesner, J.S. et al. Receiver mount design, transmitter depth, and wind speed affect detection probability of acoustic telemetry transmitters in a Missouri River tributary. Anim Biotelemetry 11, 6 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-022-00313-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-022-00313-y