Abstract

Background

Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry models (EEST) are often used to evaluate microbial nutrient use efficiency, but the validity of these models under exogenous nitrogen (N) input has never been clarified. Here, we investigated the effects of long-term N addition (as urea) on microbial N use efficiency (NUE), compared EEST and 18O-labeling methods for determining NUE, and evaluated EEST’s theoretical assumption that the ratios of standard ecoenzymatic activities balance resource availability with microbial demand.

Results

We found that NUE estimated by EEST ranged from 0.94 to 0.98. In contrast, estimates of NUE by the 18O-labeling method ranged from 0.07 to 0.30. The large differences in NUE values estimated by the two methods may be because the sum of β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and leucine aminopeptidase activities in the EEST model was not limited to microbial N acquisition under exogenous N inputs, resulting in an overestimation of microbial NUE by EEST. In addition, the acquisition of carbon by N-acquiring enzymes also likely interferes with the evaluation of NUE by EEST.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that caution must be exercised when using EEST to evaluate NUE under exogenous N inputs that may skew standard enzyme assays.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Microbial nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) describes the proportion of N taken up by microorganisms that is allocated to biomass synthesis, and is a key characteristic of microbial metabolism that plays an important role in soil N cycling (Mooshammer et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2019). NUE has mostly been evaluated by isotope labeling methods. For example, 15N-labeled amino acids have been used to trace the uptake of organic N by microbes (Wild et al. 2013). However, microbes can assimilate other N sources such as inorganic N and amino sugars, apart from amino acids. Hence, this method represents amino acid use efficiency but not a fully integrated NUE (Andresen et al. 2015). Recently, 18O-labeled water has been used to determine microbial growth and NUE, because microbes can assimilate multiple N substrates, and the use of 18O-water avoids substrate addition effects (Zhang et al. 2019). Alternatively, Sinsabaugh et al. (2016) proposed a novel model based on the ecoenzymatic stoichiometric theory (EEST) and on the mass balance principle to evaluate NUE from the elemental stoichiometry of organic matter and microbial biomass, given the ratio of activities of enzymes that target carbon (C) vs. N acquisition. A growing body of studies have used the ecoenzyme model to evaluate microbial resource use efficiency in many ecosystems, including forest, farmland and grassland (Auwal et al. 2023; Chen et al. 2018b; Li et al. 2023; Lv et al. 2022; Shen et al. 2023; Sun et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2022), partly because parameter determination is rapid, relatively inexpensive and easy to evaluate (Schimel et al. 2022).

The ecoenzymatic theory argues that the resource requirements of soil microbes are reflected by the activities of specific extracellular enzymes targeting different resources in organic polymers; i.e., β-1,4-glucosidase (BG) for C acquisition, β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) and leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) for N, and acid/alkaline phosphatase (AP) for phosphorus (P), and predicts that microbes would regulate the ratios of ecoenzymatic activities to compensate for the imbalances between resource availability and microbial demand (Sinsabaugh et al. 2008). However, exogenous N input can affect microbial N-acquiring enzyme activities because microbial use of soluble resources that do not require enzyme action to acquire, including mineral forms of N, can affect resource allocation for extracellular enzyme production (Allison 2005; Moorhead et al. 2023; Schimel et al. 2022). Also, N added such as urea fertilizer would not require the action of standard indicator enzymes (NAG + LAP) and similarly affect estimates of N acquisition unless urease was assayed. Therefore, exogenous N input can skew estimates of NUE by standard ecoenzymatic stoichiometry.

The aim of this study was to test predictions of NUE by the ecoenzyme model under conditions of N addition and to compare these to measurements of NUE based on the 18O-approach. We hypothesized that the ecoenzyme model would be less applicable to estimating NUE with external N input because NAG + LAP would not accurately reflect microbial N acquisition.

Methods

Study site and soil sample collection

The study site is located in the Changbai Mountain Natural Nature Reserve in northeastern China (42.70° N, 127.63° E). This region is characterized by a typical temperate climate, with warm summers and long and cold winters. The mean annual temperature and precipitation are 4 °C and 750 mm, respectively. The ambient atmospheric N deposition rate in this area is about ~ 27 kg N ha−1 year−1. The N addition experiment consists of 12 experimental plots (50 × 50 m) in a Korean pine and broadleaf mixed forest with at least a 20-m buffer zone between plots. The dominant coniferous species are Pinus koraiensis Siebold & Zucc., and Abies holophylla Maxim., and the broad-leaved species are Corylus mandshurica Maxim., Tilia amurensis Rupr., Acer rufinerve Siebold & Zucc., and Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom. in the plots. Starting in 2014, each of these plots was randomly assigned to the following treatments (three replicates per treatment): Control (0 kg N ha−1 year−1), low N treatment (25 kg N ha−1 year−1), medium N treatment (50 kg N ha−1 year−1), and high N treatment (75 kg N ha−1 year−1). Urea was used as N fertilizer, which was spread once annually in May or June on the forest floor (Li et al. 2021). The quantity of N added in the medium N treatment and high N treatment is equivalent to about twofold and threefold of the atmospheric N deposition rate, respectively.

Soil samples were collected at the beginning of June, July, August, September, and October 2021 after eight years of experimental treatment. Before soil samples were collected, soil temperature was determined with a PT100 thermometer. Fifteen subsamples were collected from the surface soil (0–10 cm, 2.5 cm diameter cores) in each plot. Then, the subsamples in each plot were pooled and mixed to form a composite sample and transported to the laboratory in cooling boxes on ice. Each composite sample was sieved (2 mm) and then divided into three subsamples. The subsamples were stored at − 20 °C, 4 °C, or were air-dried, for extracellular enzyme activity analysis, the incubation experiment, and for the analysis of soil physicochemical properties, respectively. The incubation experiment was carried out within one week after sample collection. Soil samples in October were used to analyze soil properties.

Soil gross N mineralization analysis

We conducted two separate incubation experiments to determine microbial growth and gross N mineralization rates. Soil samples collected in June, July, and October were used to evaluate NUE by the 18O-approach. Soil temperatures in June, July, and October were 16, 21, and 7 °C, respectively. For each composite soil stored at 4 °C, we prepared three conical flasks with fresh soil (20 g oven-dry base), two of which were used for the analysis of gross N mineralization and one for determination of microbial growth and microbial biomass C and N. Soil moisture was adjusted to 60% water holding capacity (WHC) and then pre-incubated at the respective in situ soil temperature of the collection month for 24 h. For N mineralization determinations, flasks were amended with 1 ml 15NH4NO3 (at 10 atom% 15N) solution at a rate of 20 μg NH4+-N g−1 soil, respectively, after pre-incubation. These flasks were sealed with parafilm with five pinholes and incubated for 0.5 h and 48 h at the respective in situ soil temperature. Soil extractions then were carried out with 2 M KCl (1:5 (w:v)) for 1 h to terminate isotope pool dilutions assays and to measure the concentrations and 15N enrichments of NH4+-N at 0.5 h (first flask) and 48 h (second flask) after tracer addition.

Microbial growth rate and NUE analysis

After pre-incubation, we determined microbial growth rates and calculated NUE by the 18O-H2O tracer technique (Zhang et al. 2019). For each composite soil, subsamples of 1 g soil from the remaining conical flask were weighed into 2 ml brown chromatographic vials in duplicates. One was amended with 18O-H2O (98 atom%) to reach 20 atom% of 18O in final soil water and the other one was amended with an equal volume of non-labeled water serving as a control. Then, the vials were transferred to 20-ml headspace bottles, closed with butyl rubber stoppers, and incubated at the respective in situ soil temperature for 48 h. After incubation, soil samples were stored at − 20 °C for DNA extraction and 18O abundance analysis. The rest of the pre-incubated soil was used for determination of microbial biomass (see below).

Soil physical and chemical properties

Soil pH was determined by a pH meter in a 2.5:1 (v:w) water to soil ratio. Soil organic matter (SOC), total N, and soil C/N ratio were determined by an elemental analyzer (vario MACRO cube, Germany). Soil texture was assayed by the pipette-sedimentation method. Soil water content was measured gravimetrically after oven drying for three days at 85 °C. Soil water holding capacity was analyzed by repeated saturation of soil in a funnel with filter paper for 2 h and draining for 8 h to approximate the water retained in soil at field capacity. Soil microbial biomass C (MBC) and microbial biomass N (MBN) were measured by the chloroform fumigation method (Vance et al. 1987). MBC and MBN were calculated as the differences in dissolved organic C and total N in extracts between non-fumigated subsamples and fumigated subsamples using conversion factors of 0.54 and 0.45, respectively. Soil NH4+-N content was assayed with a continuous flow analyzer (Skalar Analytical, Breda, The Netherlands) after extracting NH4+-N from soil with a 2 M KCl solution. The 15N abundance of NH4+-N was determined by the diffusion method (Brooks et al. 1989). NH4+-N in the KCl extracts was isolated for 15N abundance measurements by adding MgO. The liberated NH3 was trapped by acidified glass fiber filters wrapped in Teflon tape. The 15N abundance of NH4+-N was evaluated with an Elemental Analyzer (Thermo-Element Flash EA 1112, USA) coupled with an Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (IRMS; Thermo Fisher MAT 253, USA).

Soil extracellular enzyme activities

We determined the activities of β-glucosidase (BG), β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG), leucine aminopeptidase (LAP), and acid phosphatase (AP) according to Saiya-Cork et al. (2002), following modifications by Allison et al. (2009) and German et al. (2011). We used a multi-functional microplate reader (SynergyH4 Hybrid Reader, SynergyH4 BioTek, USA) with 365-nm excitation and 450-nm emission filter to evaluate fluorescence after adding 1 M NaOH to stop the reaction. The (NAG + LAP)/BG ratio indicated the ratio of N-acquiring enzyme activity to C-acquiring enzyme activity.

Soil DNA extraction and 18O abundance analysis

Total DNA in 18O-labeled and non-labeled soils was extracted using a DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantity of extracted DNA was evaluated by the Picogreen fluorescence assay (Quanti-iT™ PicoGreen dsDNA Reagent, Thermo Fisher, USA) using a multi-functional microplate reader (SynergyH4 Hybrid Reader, SynergyH4 BioTek, USA). Then, aliquots (70 μl) of the DNA extracts were added to silver capsules and dried at 45 °C for 5 h. The concentration and abundance of O originating from the DNA were analyzed by a TC/EA-IRMS system (Thermo Scientific, USA).

Calculations

Soil gross N mineralization rates (M) (ng N g−1 soil h−1) were calculated based on Eq. (1) (Kirkham & Bartholomew 1954):

where t1 and t2 represent soil extraction time, Ct1 and Ct2 represent soil NH4+-N content (μg N g−1 soil) at t1 and t2 respectively, and APEt1 and APEt2 represent 15N atom% excess of NH4+-N at t1 and t2, respectively.

The DNA produced (DNAproduced), microbial N growth rate (Ngrowth), and NUE were calculated as follows, with details given in Zhang et al. (2019). The DNA produced (ng) during the 48 h incubation was calculated based on Eq. (2):

where at%excess represents the atom% of 18O in the labeled samples minus the atom% of 18O in control samples, 31.21 is the mean weight% of O in DNA, Ototal represents the O content of the dried DNA extracts (ng), and at%label is 18O atom% of soil water at the beginning of the incubation, which was 20 atom% in this study.

Microbial N growth rate (ng N g−1 soil h−1) was calculated based on Eq. (3):

where t is incubation time (h) and DW is soil dry mass (g). The fDNA represents the conversion factor, which was calculated separately at each site to represent the ratio of MBN to soil DNA content.

NUE was calculated as given below:

We also estimated NUE based on the ecoenzyme model for each soil sample (Sinsabaugh et al. 2016):

where EEAN:C is (NAG + LAP)/BG ratio, BN:C and LN:C are the molar ratios of MBN/MBC and soil TN/SOC, respectively. KC is set to 0.5 and NUEmax is set to 1. SN:C is a scalar that represents the extent to which the allocation of enzyme activities balances the disparity between elemental compositions of available resources and microbial biomass.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures ANOVA followed by a Tukey multiple-comparison test was conducted to evaluate the effect of N addition on NUE, microbial growth rate, gross N mineralization rate, BN:C/LN:C, and EEAN:C across months. A one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey multiple-comparison test was performed to evaluate the effects of N addition on soil properties. Prior to statistical analysis, the homogeneity of variances was checked by Levene’s test and data were transformed if necessary. Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess relationships among variables. P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed in R 4.1.2 (R Core Team 2021). Figures were produced in R with the “ggplot2” package (Valero-Mora 2010).

Results

Soil pH (ranging from 4.67 to 5.02) decreased with N addition (Table 1). The contents of clay (ranging from 22.3% to 35.7%), silt (ranging from 32.3 to 38.6%), and sand (ranging from 26.88 to 45.4%) did not change with N addition. The SOC and TN contents were lowest in the low N treatments, while soil C/N remained constant across N addition treatments.

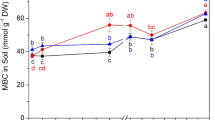

NUE estimated by the ecoenzyme model ranged from 0.94 to 0.98 and did not change with N addition (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table S1). NUE estimated by the 18O-approach ranged from 0.07 to 0.30 and tended to decrease with N addition (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1). Microbial N growth rate showed a weak tendency to decrease with N addition, while gross N mineralization rate did not change (Additional file 1: Fig. S2 and Table S1). EEAN:C and BN:C/LN:C did not change with N addition (Additional file 1: Fig. S1 and Table S1). No relationship was found between EEAN:C and BN:C/LN:C (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

Estimates of soil microbial NUE by the enzyme stoichiometry method for N addition treatments. CK control (0 kg N ha−1 year−1), LN low N addition (25 kg N ha−1 year−1), MN medium N addition (50 kg N ha−1 year−1), HN high N addition (75 kg N ha−1 year−1). Different letters indicate a significant difference among N addition treatments in a specific month. Data presented are mean and standard error (n = 3)

Estimates of soil microbial NUE by the 18O-based method for N addition treatments. CK, control (0 kg N ha−1 year−1); LN low N addition (25 kg N ha−1 year−1), MN medium N addition (50 kg N ha−1 year−1), HN high N addition (75 kg N ha−1 year−1). Different letters indicate a significant difference among N addition treatments in a specific month. Data presented are mean and standard error (n = 3)

Discussion

The NUE values estimated by the 18O-approach (ranging from 0.07 to 0.30) were within the previously reported range of 0.02 to 0.73 in forest ecosystems (Sun et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2019). These reported NUE values likely varied greatly because they are affected by temperature, moisture, soil properties, and other factors (Zhang et al. 2019).

In contrast, the NUE values estimated by the ecoenzyme model were much higher than those estimated by the 18O-approach (Fig. 2). We believe that this difference was the result of reduced contributions of NAG + LAP to microbial N acquisition under N addition, which led to an overestimation of NUE by the EEST method. We found that the ratios of N-acquiring enzyme activity to C-acquiring enzyme activity (EEAN:C) were low (< 0.5) (Additional file 1: Fig. S1), which overestimates NUE by the ecoenzyme model (Eqs. 5 and 6). Possibly other N-acquiring enzymes were important for microbial N acquisition under N addition (such as urease), however, these enzymes were not included in the calculations (Eqs. 5 and 6). These results imply that β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and leucine aminopeptidase activities cannot accurately indicate microbial N acquisition under this external N input which decouples the expected relationships between N:C in microbial biomass and soil resources as balanced by N- to C-acquiring enzyme activities (Additional file 1: Fig. S3) (Sinsabaugh & Follstad Shah 2012). In addition, soluble resources (such as mineral N deposition) can be assimilated directly by microbes without enzyme catalysis, which similarly affects the estimation of microbial NUE by enzyme model. Taken together, we argue that ecoenzyme stoichiometry does not accurately estimate NUE with external N inputs that affect microbial N acquisition outside the framework of the ecoenzyme stoichiometry model based on the standard indicator enzymes (NAG + LAP), consistent with our hypothesis.

N-acquiring enzymes may be produced for C-liberation under exogenous N inputs, which also interferes with the estimation of NUE by the enzyme model. The ecoenzymatic theory predicts that EEAN:C should decrease with N addition because the relative activities of NAG and LAP should decrease compared to BG (Sinsabaugh & Follstad Shah 2012; Sinsabaugh et al. 2008). However, we did not find significant changes in the (NAG + LAP)/BG ratio (EEAN:C) with N addition (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). This is inconsistent with ecoenzyme stoichiometry theory, but reported by previous meta-analyses that N addition had negligible effects on the ratio of total C- to N-acquiring enzyme activities (Chen et al. 2018a; Jian et al. 2016). This may be because microbes can utilize N-acquiring enzymes for acquiring C under C-poor and/or N-rich conditions (Mori 2020). N addition can stimulate microbial activity and growth by increasing the acquisition of C from organic N substrates, that reduces NUE but in turn increases the production of microbial residues containing chitin, peptidoglycans, and proteins (Hu et al. 2022; Liang et al. 2019; Mori et al. 2021; Zheng et al. 2022). As a result, N-acquiring enzymes may be increasingly important to obtain C under N addition.

The 18O-approach estimated microbial growth by tracing the incorporation of 18O from water into DNA; however, the concurrent mortality of growing microorganisms and the growth of cell size (without DNA replication) can cause an underestimation of microbial growth and therefore of element use efficiencies. To decrease the effect of microbial turnover, the 18O-approach is usually applied only over short-term measurement periods (1–3 days). In addition, microbial extracellular products, which may contain C and N or both, are currently not included in estimations of microbial element use efficiencies due to methodological limitations (Geyer et al. 2016). This causes uncertainty in NUE estimation, which needs to be resolved in the future.

Conclusions

NUE values estimated by the ecoenzyme model were significantly higher than those estimated by the 18O-labeling method and did not change with N addition. This is because the NAG + LAP cannot accurately reflect microbial N acquisition under conditions with external N inputs. In summary, our results suggest that the ecoenzyme model should be used with caution in managed ecosystems.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MBC:

-

Microbial biomass carbon

- MBN:

-

Microbial biomass nitrogen

- BN :C :

-

MBN/MBC ratio

- SOC:

-

Soil organic carbon

- TN:

-

Total nitrogen

- LN :C :

-

TN/SOC ratio

- EEST:

-

Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry models

- NUE:

-

Nitrogen use efficiency

- BG:

-

β-Glucosidase

- NAG:

-

β-N-acetylglucosaminidase

- LAP:

-

Leucine aminopeptidase

- EEAN :C :

-

(NAG + LAP)/BG ratio

- Ngrowth :

-

Microbial nitrogen growth rate

- M :

-

Gross nitrogen mineralization rate

References

Allison SD (2005) Cheaters, diffusion and nutrients constrain decomposition by microbial enzymes in spatially structured environments. Ecol Lett 8:626–635

Allison SD, LeBauer DS, Ofrecio MR, Reyes R, Ta A-M, Tran TM (2009) Low levels of nitrogen addition stimulate decomposition by boreal forest fungi. Soil Biol Biochem 41:293–302

Andresen LC, Bode S, Tietema A, Boeckx P, Rütting T (2015) Amino acid and N mineralization dynamics in heathland soil after long-term warming and repetitive drought. Soil 1:341–349

Auwal M, Sun H, Adamu UK, Meng J, Van Zwieten L, Pal Singh B, Luo Y, Xu J (2023) The phosphorus limitation in the post-fire forest soils increases soil CO2 emission via declining cellular carbon use efficiency and increasing extracellular phosphatase. Catena 224:106968

Brooks P, Stark JM, McInteer B, Preston T (1989) Diffusion method to prepare soil extracts for automated nitrogen-15 analysis. Soil Sci Soc Am J 53:1707–1711

Chen H, Li D, Zhao J, **ao K, Wang K (2018a) Effects of nitrogen addition on activities of soil nitrogen acquisition enzymes: a meta-analysis. Agric Ecosyst Environ 252:126–131

Chen L, Liu L, Mao C, Qin S, Wang J, Liu F, Blagodatsky S, Yang G, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Yu J, Yang Y (2018b) Nitrogen availability regulates topsoil carbon dynamics after permafrost thaw by altering microbial metabolic efficiency. Nat Commun 9:3951

German DP, Weintraub MN, Grandy AS, Lauber CL, Rinkes ZL, Allison SD (2011) Optimization of hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme methods for ecosystem studies. Soil Biol Biochem 43:1387–1397

Geyer KM, Kyker-Snowman E, Grandy AS, Frey SD (2016) Microbial carbon use efficiency: accounting for population, community, and ecosystem-scale controls over the fate of metabolized organic matter. Biogeochemistry 127:173–188

Hu J, Huang C, Zhou S, Liu X, Dijkstra FA (2022) Nitrogen addition increases microbial necromass in croplands and bacterial necromass in forests: a global meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem 165:108500

Jian S, Li J, Chen J, Wang G, Mayes MA, Dzantor KE, Hui D, Luo Y (2016) Soil extracellular enzyme activities, soil carbon and nitrogen storage under nitrogen fertilization: a meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem 101:32–43

Kirkham D, Bartholomew WV (1954) Equations for following nutrient transformations in soil, utilizing tracer data. Soil Sci Soc Am J 18:33–34

Li J, Sang C, Yang J, Qu L, **a Z, Sun H, Jiang P, Wang X, He H, Wang C (2021) Stoichiometric imbalance and microbial community regulate microbial elements use efficiencies under nitrogen addition. Soil Biol Biochem 156:108207

Li Q, Shi J, Li G, Hu J, Ma R (2023) Extracellular enzyme stoichiometry and microbial resource limitation following various grassland reestablishment in abandoned cropland. Sci Total Environ 870:161746

Liang C, Amelung W, Lehmann J, Kästner M (2019) Quantitative assessment of microbial necromass contribution to soil organic matter. Glob Change Biol 25:3578–3590

Lv F-l, Zheng W, Zhai B-n, Li Z-y (2022) Cover crop** and chemical fertilizer seasonally mediate microbial carbon and phosphorus metabolisms in an apple orchard: evidence from the enzymatic stoichiometry method. Appl Soil Ecol 178:104579

Moorhead D, Cui Y, Sinsabaugh R, Schimel J (2023) Interpreting patterns of ecoenzymatic stoichiometry. Soil Biol Biochem 180:108997

Mooshammer M, Wanek W, Hämmerle I, Fuchslueger L, Hofhansl F, Knoltsch A, Schnecker J, Takriti M, Watzka M, Wild B, Keiblinger KM, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Richter A (2014) Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon:nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nat Commun 5:3694

Mori T (2020) Does ecoenzymatic stoichiometry really determine microbial nutrient limitations? Soil Biol Biochem 146:107816

Mori T, Aoyagi R, Kitayama K, Mo J (2021) Does the ratio of β-1,4-glucosidase to β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase indicate the relative resource allocation of soil microbes to C and N acquisition? Soil Biol Biochem 160:108363

R Core Team (2021) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Saiya-Cork KR, Sinsabaugh RL, Zak DR (2002) The effects of long term nitrogen deposition on extracellular enzyme activity in an Acer saccharum forest soil. Soil Biol Biochem 34:1309–1315

Schimel J, Weintraub MN, Moorhead D (2022) Estimating microbial carbon use efficiency in soil: Isotope-based and enzyme-based methods measure fundamentally different aspects of microbial resource use. Soil Biol Biochem 169:108677

Shen L, Ye S, Liu H, Deng X, He P, Cheng F (2023) Linkage between leaf-litter-soil, microbial resource limitation, and carbon-use efficiency in successive Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) plantations. Forests 14:357

Sinsabaugh RL, Follstad Shah JJ (2012) Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry and ecological theory. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 43:313–343

Sinsabaugh RL, Lauber CL, Weintraub MN, Ahmed B, Allison SD, Crenshaw C, Contosta AR, Cusack D, Frey S, Gallo ME, Gartner TB, Hobbie SE, Holland K, Keeler BL, Powers JS, Stursova M, Takacs-Vesbach C, Waldrop MP, Wallenstein MD, Zak DR, Zeglin LH (2008) Stoichiometry of soil enzyme activity at global scale. Ecol Lett 11:1252–1264

Sinsabaugh RL, Turner BL, Talbot JM, Waring BG, Powers JS, Kuske CR, Moorhead DL, Shah JJF (2016) Stoichiometry of microbial carbon use efficiency in soils. Ecol Monogr 86:172–189

Sun Y, Wang C, Ruan H (2022) Increased microbial carbon and nitrogen use efficiencies under drought stress in a poplar plantation. For Ecol Manage 519:120341

Sun L, Li J, Qu L, Wang X, Sang C, Wang J, Sun M, Wanek W, Moorhead DL, Bai E, Wang C (2023) Phosphorus limitation reduces microbial nitrogen use efficiency by increasing extracellular enzyme investments. Geoderma 432:116416

Valero-Mora PM (2010) ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. J Stat Softw 35:1–3

Vance ED, Brookes PC, Jenkinson DS (1987) An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol Biochem 19:703–707

Wang X, Wu D, Li S, Chen T, Chen R, Yin L, Yao X, Chen G (2022) Effects of C:N imbalance on soil microbial physiology in subtropical tree plantations associated with ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Geoderma 422:115932

Wild B, Schnecker J, Bárta J, Čapek P, Guggenberger G, Hofhansl F, Kaiser C, Lashchinsky N, Mikutta R, Mooshammer M, Šantrůčková H, Shibistova O, Urich T, Zimov SA, Richter A (2013) Nitrogen dynamics in turbic cryosols from Siberia and Greenland. Soil Biol Biochem 67:85–93

Zhang S, Zheng Q, Noll L, Hu Y, Wanek W (2019) Environmental effects on soil microbial nitrogen use efficiency are controlled by allocation of organic nitrogen to microbial growth and regulate gross N mineralization. Soil Biol Biochem 135:304–315

Zheng H, Vesterdal L, Schmidt IK, Rousk J (2022) Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry can reflect microbial resource limitation, substrate quality, or both in forest soils. Soil Biol Biochem 167:108613

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the editor and the reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0608100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32001174 and 32101378), the Major Program of Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IAEMP202201), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (ZDBS-LY-DQC019), and Project funded by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022M710004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. and C.W. designed the study. L.S., Y.C. and S.L. performed the experiment. L.S., D.M. and W.W. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest or competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Results of repeated-measures analysis of variance (F values) showing effects of N addition and month on microbial metabolism parameters. Fig. S1 Effects of N addition on EEAN:C (A) and BN:C/LN:C (B). EEAN:C, the ratio of enzymatic N (LAP+NAG) vs. C (BG) acquisition activities; BN:C/LN:C, N:C ratio of microbes vs. soil; BG, β-1,4-glucosidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1); NAG, β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1); LAP, leucine aminopeptidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1); CK, control (0 kg N ha-1 year-1); LN, low N addition (25 kg N ha-1 year-1); MN, medium N addition (50 kg N ha-1 year-1); HN, high N addition (75 kg N ha-1 year-1). Different letters indicate a significant difference among N addition treatments in a specific month. Data presented are mean and standard error (n = 3). Fig. S2 Effects of N addition on microbial N growth rate (A) and gross N mineralization rate (B). CK, control (0 kg N ha-1 year-1); LN, low N addition (25 kg N ha-1 year-1); MN, medium N addition (50 kg N ha-1 year-1); HN, high N addition (75 kg N ha-1 year-1). Different letters indicate a significant difference among N addition treatments in a specific month. Data presented are mean and standard error (n = 3). Fig. S3 Relationship between EEAN:C and BN:C/LN:C. EEAN:C, the ratio of enzymatic N (LAP+NAG) and C (BG) acquisition activities; BN:C/LN:C, N:C ratio of microbes vs. soil; BG, β-1,4-glucosidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1); NAG, β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1); LAP, leucine aminopeptidase (nmol g-1 soil h-1).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, L., Moorhead, D.L., Cui, Y. et al. Exogenous nitrogen input skews estimates of microbial nitrogen use efficiency by ecoenzymatic stoichiometry. Ecol Process 12, 46 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-023-00457-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-023-00457-6