Abstract

Background

Grassland conversion to cropland is a prevailing change of land use in traditionally nomadic areas, especially in the Mongolian Plateau. We investigated the effects of grassland conversion followed by continuous cultivation on soil properties and microbial community characteristics in Horqin Sandy Land, a typical agro-pastoral transition zone of Northern China. Soil samples were collected from the topsoil (upper 20 cm) across a 60-year cultivation chronosequence (5, 15, 25, 35 and 60 years) and unconverted native grassland. Soil physico-chemical properties were determined and high-throughput sequencing was used to assess microbial community diversity and composition.

Results

Grassland cultivation resulted in changes to soil properties in both the short and longer term. Initially, it significantly increased soil bulk density (BD), electrical conductivity (EC), soil total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP) and available potassium (AK) concentrations, while reducing soil water content (SWC) and soil organic carbon content (SOC). Over the next 35–55 years of continuous cultivation, the trend for most of these characteristics was of reversion towards values nearer to those of native grassland, except for SOC which remained highly depleted. Cultivation of grassland substantially altered soil microbial communities at phylum level but there was no significant difference in microbial α-diversity between native grassland and any cropland. However, soil bacterial and fungal community structures at phylum level in the croplands of all cultivation years were different from those in the native grasslands. Heatmaps further revealed that bacterial and fungal structures in cropland tended to become more similar to native grassland after 15 and 25 years of cultivation, respectively. Redundancy analysis indicated that SOC, EC and BD were primary determinants of microbial community composition and diversity.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that agricultural cultivation of grassland has considerable effects on soil fertility and microbial characteristics of Horqin Sandy Land. Intensive high-yield forage grass production is proposed as an alternative to avoid further native grassland reclamation, while meeting the grazing development needs in the ethnic minority settlements of eco-fragile regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

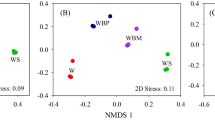

Grasslands occupy more than 40% of the world's land surface and are highly susceptible to anthropogenic activity and climate change (Yang et al. 2022). In addition to supplying dairy products and meat for human consumption, as a major biome in terrestrial ecosystem, they have a role in resisting desertification, regulating the climate change, and maintaining biodiversity (White et al. 2000; Wang et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2022), and they are sensitive to changes in their environment (Maron et al. 2018; Ren et al. 2019). Therefore, changes in soil physico-chemical properties resulting from land use and management can have an impact on the composition and structure of the microbial communities (Ferreira et al. 2016; Hu et al. 2021). Emerging studies on the impact of crop** have revealed that conversion to arable crops could alter the proportion of copiotrophs and oligotrophs and generally increase soil microbial diversity, as a result of fertilization, irrigation and tillage (Fierer et al. 2012; He et al. 2017; Dos Santos et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). On the other hand, tillage and continual fertilization in barren drylands may have opposite effects on the species composition of soil microbes (Wang et al. 2010b; Zhou et al. 2016). Even though much previous work has focused on the impacts of human activities on semi-arid ecosystems with harsh environmental conditions around the world (Li et al. The study was carried out in Ulanaodu village, Wengniute County, near the Desertification Ecological Experimental Station of the Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, located in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (43°02′ N, 119°39′E, 480 m a.s.l). The experimental area is situated at the southwestern fringe of Horqin Sandy Land, in an ecotone between typical cultivation and husbandry in China. It has a temperate continental climate, with a mean annual temperature (1980–2017) of 7.3 °C, representing a brief hot summer but a long cold winter. The average annual precipitation is 318 mm, with nearly 70% falling between June and August during the growing season. The annual potential evaporation is c. 2200 mm. The average wind velocity is 3.6 m s−1, with the prevailing direction northwest in the spring and winter, and southwest in the summer and autumn. The soil is classified as an aeolian sandy soil according to the soil taxonomy system of China and as an Orthi-sandic Entisol according to the FAO–UNESCO classification. It is characterized by susceptibility to wind erosion due to its coarse texture (Cao et al. 2008). The undulating landscape supports native grassland with sparsely distributed trees of Ulmus pumila. The indigenous vegetation comprises a typical Mongolian flora of relatively high diversity. Dominant species include the shrubs Caragana microphylla and Salix flavida, and annual and perennial herbs, such as Chenopodium acuminatum, Artemisia scoparia, Artemisia wudanica and Bassia dasyphylla. The vegetation cover is 40–85% with 150–250 g m−2 average standing dry biomass. Maize (Zea mays L.) most commonly has been cultivated as a monoculture since native grassland was converted to cropland. Seeds have been generally sown in early May using a mechanical drill, with plants spaced at 0.50 m between rows and 0.30 m between plants. Chemical fertilizer and water irrigation have been applied during the growing season since 1990. Between 1990 and 2005, annual fertilizer application included 150 kg ha−1 of urea, 75 kg ha−1 of diammonium phosphate and 35 t ha−1 of sheep and cattle manure; after 2005, 350 kg ha−1 compound fertilizer (N 18% - P2O5 6% - K2O 6%) and 75 kg ha−1 of urea and 20 t ha−1 of manure were employed. Before 1990, extensive cultivation with no chemical fertilizer or manure as well as irrigation had been adopted. Fertilizers were applied simultaneously with maize sowing. Annual irrigation of 1800 m3 ha−1, pumped from groundwater, was applied to alleviate drought at the seedling, tasseling and spinning stages. Herbicide and pesticide applications were required for the control of weeds and pests. Maize cobs were harvested and nearly all of the stalks were removed for fodder at the beginning of October every year. In the control native grasslands, grazing was not permitted during the growing season from May to September, and around 70% of the aboveground biomass was harvested at the end of October each year for hay feed. No fertilizers, pesticides or irrigation were employed there. More details of the annual agricultural management in grassland and farmlands are shown in Table 1. Historically, the land of Ulanaodu village was 700 ha of intact native grassland with uniform soil conditions. Due to the farmland expansion around this village, grassland has been converted and subsequently cultivated continuously. A mosaic of areas with different cultivation histories was chosen for space-for-time substitution analysis. Areas with specific cultivation durations of farmlands 5, 15, 25, 35 and 60 years, respectively (CUL5, CUL15, CUL25, CUL35 and CUL60) were identified by fieldwork and consultation with local pastoralists and staff from adjacent experimental station. Precise reclamation and continuity of cultivation history had been meticulously recorded by annual survey since the station establishment and the organization of local desertification combating. Areas of native grassland (CUL0) were also taken as controls. Six areas were identified to represent each cultivation duration treatment, and a 1 ha plot was located randomly within each. In order to be representative as possible, the distance between replicates within a landscape mosaic of 300 ha farmland was at least 500 m. Thus, there were 36 plots (6 treatments × 6 replicates) in total in the experiment.

Soil samples were collected from each plot at a depth of 0–20 cm in late October 2020. Six soil cores were obtained using a spade at randomly selected locations at least 50 m apart and 20 m from the boundary (to prevent edge effects) in each plot. After manually removing surface debris, they were combined into one bulk sample. Subsequently samples were separated into two parts. The first was stored and transported in a sterile polyvinyl chloride pipe on ice, for high-throughput sequencing. The remainder was transported in a zip-top plastic bag to the lab, where it was air dried, visible roots and litter were removed, and then it was passed through a 2-mm sieve before chemical analysis. Twelve additional undisturbed bulk soil samples were taken from the same depth in each treatment using customized stainless-steel cutting rings. Half of these samples were used to determine bulk density, while the remainder were used to measure soil water content. Soil bulk density was measured using the cores of known volume (Blake and Hartage 1986). Soil water content was determined by oven drying at 105 °C. Soil pH and electrical conductivity (EC) were measured in a soil–water aqueous extract (1:2.5 by mass) after 30 min shaking at low speed (Orion Star 310p, Thermo, USA). Soil organic carbon was determined by an external heating method using potassium dichromate (Carter and Gregorich 2007). The total N was determined by titration of distillates after Kjeldahl digestion (Lu 1999). The molybdenum–antimony anti-colorimetric method and flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry, respectively, were used to determine soil available phosphorus (AP) and potassium (AK) (Lu 1999). Soil DNA extraction, purification and labeling were performed as described by Zhang et al. (2022). DNA from soil samples was extracted using an OMEGA Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and then stored at − 20 °C. A spectrophotometer (NanoDrop NC2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1 percent agarose gel electrophoresis were used to measure the extracted DNAs. All DNA samples were stored at – 80 °C prior to PCR amplification and sequencing. The bacterial V3–V4 region of 16S rRNA was amplified with forward primer 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and reverse primer 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). PCR amplification targeting the fungal ITS-V1 region was carried out using the forward primer ITS5 (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′) and the reverse primer ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′) (Tang et al. 2022). The amplicons were analyzed by paired-end sequencing based on the Illumina platform by the Personal Biotechnology Company, Shanghai, China. With minor modifications, microbiome bioinformatics were carried out using QIIME 2 2019.4 in accordance with the official tutorials (https://docs.qiime2.org/2019.4/tutorials). The quality of raw high-throughput sequences was evaluated. Trim-paired primer sequence fragments and mismatched primer sequences were eliminated using cutadapt. Selected sequences were quality-filtered, denoised, merged, and chimeras were eliminated through the use of Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 (DADA2) techniques (Callahan et al. 2016). DADA2 deduces the sequences and produces amplicon sequence variations (ASVs) that are identical. Only de-replication or grou** based on 100% similarity was performed for DADA2. At that sequencing depth, each sample and its relative abundance would predict ASVs. The SILVA Release 132 (http://www.arb-silva.de) and UNITE Release 8.0 (https://unite.ut.ee) databases were used to classify ASVs as bacteria or fungi (Bokulich et al. 2018). Sequences were rarefied for data analyses. Raw sequencing files were deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with the accession number “PRJNA885802”. The ASV table in QIIME 2 was used to calculate the microbial alpha-diversity parameters including Chao1 richness, Observed species, Shannon diversity index, and Simpson index. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), based on Bray–Curtis distance and hierarchical clustering, was carried out using the Vegan package within the statistical software R 3.6.1 to examine the similarity and variation of community composition across different treatments. Soil properties and microbial community characteristics were tested for significant differences by one-way ANOVA with the Holm–Bonferroni test, or by the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test, depending on whether data were normally distributed or not. Redundancy analysis was employed to assess the relationships between soil properties and microbial characteristics using Canoco 5.0 software. Additional statistical tests were performed and graphs visualized using OriginPro 2019b (Origin Lab Inc., Northampton, MA, USA). The chronosequence showed that cultivation of the grassland considerably changed soil properties, in both the short and longer terms (Table 2). The initially low bulk density (BD) in native grassland (CUL0) increased significantly after the first 5 years of cultivation and then declined steadily to become not significantly different from its original value after 60 years. Electrical conductivity (EC) peaked after 15 years, but it had also returned to near its initial value after 60 years. Soil water content (SWC) showed the inverse trend, drop** rapidly after 5 years and then progressively increasing again. Soil pH varied little ranged from 7.73 to 8.06, with no obvious trend over time. The most striking effect on nutrient status was a reduction in soil organic carbon (SOC) by 60% after 5 years of cultivation (Fig. 1A). It reached a minimum after 25 years and subsequently showed a trend of slow recovery. In contrast, total nitrogen (TN), available phosphorus (AP) and available potassium (AK) contents had increased after 5 years, dramatically by 179% in the case of AK (Fig. 1B–D). The content of all three of these essential nutrients had dropped again sharply after 15 years of cultivation; subsequently there was another slow increase with cultivation period, which resulted in TN and AP approaching the values in uncultivated grassland again after 60 years. However, the content of AK with 60 years of cultivation was about twice the value in uncultivated native grassland (Fig. 1D). Across all soil samples, bacterial communities at phylum level were dominated by Actinobacteria, which accounted for 28–45% of relative abundance, followed by Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria (Fig. 2A and Additional file 1: Table S1). When grasslands were transformed into croplands, the mean relative abundances of Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria significantly decreased. After 5 years of cultivation, they were reduced by 23% and 19%, respectively. Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria reached a minimum after 35 years and 15 years, respectively. There were no appreciable changes in the mean relative abundance of Proteobacteria in the chronosequence. Native grassland (CUL0) had the lowest representations of Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, Gemmatimonadetes and Bacteroidetes, at 7.6%, 1.7%, 2.9% and 2.0%, respectively. All cultivation treatments increased the proportions of these phyla to varying degrees. The treatment with 60 years of cultivation yielded the highest values of Chloroflexi and Gemmatimonadetes, significantly higher than CUL0 and CUL5, whereas Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes were greatest after 15 years, only significantly higher than CUL0. The phylum Ascomycota dominated the fungal community in the soil samples, accounting for 70–88% of relative abundance across all cultivation periods, with Basidiomycota the next most abundant (Fig. 2B and Additional file 2: Table S2). The relative abundance of Ascomycota was significantly increased by cultivation, with abundances after 5 and 60 years greater by 26% and 19%, respectively. The mean relative abundance of Mortierellomycota also increased significantly as a result of cultivation, reaching a maximum of 4.1% after 60 years. Cultivation decreased the relative abundance of Basidiomycota, although there was no significant difference among treatments with various cultivation years. There was no statistically significant difference among any index of alpha diversity along the chronosequence for either bacteria or fungi (Table 2). However, nearly all of the diversity indices tended to be lower after cultivation than in the native grassland soils. Fungi were more sensitive to the effects of grassland cultivation than bacteria. For fungi, the Shannon and Chao1 indices in the CUL5 treatment were lower by 15.8% and 6.4%, respectively, than for native grassland (CUL0). The lowest Pielou index value for fungi was obtained after 35 years of cultivation, whereas the minimum Simpson index value was after 5 years of cultivation (Table 3). The beta diversity of bacteria and fungi was represented in NMDS ordinations, with stress values of 0.0955 and 0.112, respectively (Fig. 3). For both groups, the first axis clearly differentiated the communities observed in native grassland from those of various cultivation periods. Plots with the same cultivation period tended to cluster together, but there was no clear trend with cultivation duration. Heatmaps further revealed that soil bacterial structures at phylum level in the uncultivated grassland were most similar to those after 15 years of cultivation and least similar to those after 25 years of cultivation (Fig. 4A). For fungal community structures, uncultivated grassland was most similar to those after 25 years and least similar to those after 60 years of cultivation (Fig. 4B). Redundancy analysis revealed that the composition of the soil bacterial community at phylum level and all the alpha diversity indices were strongly linked with SOC (p = 0.002), EC (p = 0.006), and BD (p = 0.01), accounting for 19.7%, 7.8%, and 8.8% of the total community variation, respectively (Fig. 5A). The first and second ordination axes explained 26.7% and 15.4% of the overall variation, respectively. SOC and AK were significantly and positively related to the abundance of Actinobacteria and Pielou index, while BD and EC were significantly and positively correlated with Proteobacteria and Simpson index. Fungal alpha diversity indices and main community composition at the phylum level were closely linked to BD and SOC, accounting for 13.0% and 10.1% of variation, respectively. The first and second axes, respectively, described 29.7% and 11.5% of the entire variation in the fungal community, collectively accounting for 41.2% of it (Fig. 5B). SOC and AK were significantly, positively related to the abundance of Basidiomycota, whereas BD and SWC were similarly associated with Ascomycota, and EC with Mortierellomycota. An increasing number of farmers and nomads have chosen to reclaim grasslands, woodlands, bare lands and even desert lands to expand crop production areas and meet their food demands, worldwide (Szoboszlay et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2002; Tang et al. 2020a). Agricultural conversion of grassland promoted the proportions of Ascomycota and Mortierellomycota, which suggested that this land-use change provided soil organic matter and nutrient availability for specific microbial species. Pathogenic fungal species that cause crop disease are typically found among Basidiomycota (Li et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2021). Compared to natural grassland, cultivation decreased the abundance of Basidiomycota. Possible explanations for this include the changes of C/N ratio and SOC. Microbial community composition and its proportional representation determine microbial diversity (Ferreira et al. 2016; Francioli et al. 2016), and more stable ecosystems are frequently associated with higher levels of microbial diversity (Maron et al. 2018). Our results suggested that grassland cultivation merely altered microbial community composition but had little effect on alpha diversity. Li et al. (2018) found that farming in the desert did not always lead to an increase in the diversity of the microbial community but did cause changes in the abundant species, which was similar to our findings. Earlier research had indicated that long-term farming might affect soil microbial community structure (Li et al. 2014, 2019) demonstrated that SOC controlled the composition of the bacterial population in semi-arid agricultural ecosystems. Moreover, BD was significantly positively correlated with Proteobacteria and Ascomycota, while negatively with Actinobacteria. This might be accounted for by the fact that tillage and irrigation altered soil macro-aggregation and compaction, which in turn might have affected dominant bacterial proliferation by modulating soil oxygen availability (Kihara et al. 2012; Lu et al. 2019). The dominant microbial phyla and alpha diversity indices were shown to be significantly correlated, and their correlations with SOC and BD further demonstrated the significance of these soil factors as key determinants in sha** microbial community structure. Intensive agricultural practices yield relatively high aboveground biomass for feeding livestock and human food demands when grassland is converted to arable land, albeit at the expense of massive inputs of water, chemical fertilizer, and pesticides. SOC and other nutrient changes were expected to occur primarily during the initial decade following grassland cultivation (Tang et al. The data generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author. Abegaz A, Winowiecki LA, Vagen TG, Langan S, Smith JU (2016) Spatial and temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon in landscapes of the upper Blue Nile Basin of the Ethiopian Highlands. Agric Ecosyst Environ 218:190–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2015.11.019 Bao YY, Jan J, Guo ZY, Chen RR, Wu M, Li ZP, Lin XG, Feng YZ (2021) Important ecophysiological roles of non-dominant Actinobacteria in plant residue decomposition, especially in less fertile soils. Microbiome 9:84. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-021-01032-x Blake GR, Hartage KH (1986) Bulk density. In: Methods of Soil Analysis. ASA and SSSA, Madison,WI Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Ram RJ, Matthew D, Evan B, Rob K, Huttley GA, Gregory CJ (2018) Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome 6:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z Callahan BJ, Mcmurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson A, Holmes SP (2016) DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods 13:581–583. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3869 Cao CY, Jiang DM, Teng XH, Jiang Y, Liang WJ, Cui ZB (2008) Soil chemical and microbiological properties along a chronosequence of Caragana microphylla Lam. plantations in the Horqin sandy land of Northeast China. Appl Soil Ecol 40:78–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2008.03.008 Carter MR, Gregorich EG (2007) Soil sampling and methods of analysis. CRC Press, Boca Raton Chen HH, Dai ZM, Veach AM, Zheng JQ, Xu JM, Schadt CW (2020) Global meta-analyses show that conservation tillage practices promote soil fungal and bacterial biomass. Agric Ecosyst Environ 293:106841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106841 Cheng ZB, Chen Y, Zhang FH (2019) Effect of crop** systems after abandoned salinized farmland reclamation on soil bacterial communities in arid northwest China. Soil Tillage Res 187:204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.12.015 Ding F, Hu YL, Li LJ, Li A, Shi SW, Lian PY, Zeng DH (2013) Changes in soil organic carbon and total nitrogen stocks after conversion of meadow to cropland in Northeast China. Plant Soil 373:659–672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1827-5 Dos Santos UJ, De Medeiros EV, Duda GP, Marques MC, de Souza ES, Brossard M, Hammecker C (2019) Land use changes the soil carbon stocks, microbial biomass and fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) in Brazilian semiarid area. Arch Agron Soil Sci 65:755–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2018.1523544 Du Y (2019) Analysis of land cover change and driving factors in Horqin Sandy Land in recent 20 years. Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai Ferreira ACC, Leite LFC, de Araujo ASF, Eisenhauer N (2016) Land-use type effects on soil organic carbon and microbial properties in a semi-arid region of Northeast Brazil. Land Degrad Dev 27:171–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2282 Fierer N, Lauber CL, Ramirez KS, Zaneveld J, Bradford MA, Knight R (2012) Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J 6:1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.159 Francioli D, Elke S, Guillaume L, Tesfaye W, François B, Thomas R (2016) Mineral vs. organic amendments: microbial community structure, activity and abundance of agriculturally relevant microbes are driven by long-term fertilization strategies. Front Microbiol 7:289. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01446 Gilbert JA, Field D, Swift P, Newbold L, Oliver A, Smyth T, Somerfield PJ, Huse S, Joint I (2010) The seasonal structure of microbial communities in the Western English Channel. Environ Microbiol 11:3132–3139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02017.x Gongbuzeren LYB, Li WJ (2015) China’s rangeland management policy debates: what have we learned? Rangel Ecol Manag 68:305–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2015.05.007 Guo LB, Gifford RM (2002) Soil carbon stocks and land use change: a meta analysis. Glob Chang Biol 8:345–360. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1354-1013.2002.00486.x He YT, Xu MG, Qi YC, Dong YS, He XH, Li JW, Liu XC, Sun LJ (2017) Differential responses of soil microbial community to four-decade long grazing and cultivation in a semi-arid grassland. Sustainability 9:128. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010128 Hu YG, Wang ZR, Zhang ZS, Song NP, Zhou HK, Li YK, Wang YN, Li CS, Hale L (2021) Alteration of desert soil microbial community structure in response to agricultural reclamation and abandonment. Catena 207:105678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105678 Kihara J, Martius C, Bationo A, Thuita M, Lesueur D, Herrmann L, Amelung W, Vlek PLG (2012) Soil aggregation and total diversity of bacteria and fungi in various tillage systems of sub-humid and semi-arid Kenya. Appl Soil Ecol 58:12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2012.03.004 Li FR, Zhao WZ, Liu JL, Huang ZG (2009) Degraded vegetation and wind erosion influence soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation in sandy grasslands. Plant Soil 317:79–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9789-8 Li XG, Ding CF, Zhang TL, Wang XX (2014) Fungal pathogen accumulation at the expense of plant-beneficial fungi as a consequence of consecutive peanut monoculturing. Soil Biol Biochem 72:11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.01.019 Li FR, Liu JL, Ren W, Liu LL (2018) Land-use change alters patterns of soil biodiversity in arid lands of northwestern China. Plant Soil 428:371–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3673-y Li XB, He HB, Zhang XD, Yan XX, Six J, Cai ZC, Barthel M, Zhang JB, Necpalova M, Ma QQ, Li ZA (2019) Distinct responses of soil fungal and bacterial nitrate immobilization to land conversion from forest to agriculture. Soil Biol Biochem 134:81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.03.023 Li F, Zhang SQ, Wang Y, Li Y, Li PP, Chen L, Jie XL, Hua DS, Feng B, Yue K, Han YL (2020a) Rare fungus, Mortierella capitata, promotes crop growth by stimulating primary metabolisms related genes and resha** rhizosphere bacterial community. Soil Biol Biochem 151:108017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.108017 Li JB, Liu GM, Kwak JH, Chang SX, Gao HC, Wu QC, Yang JS, Chen JL (2020b) Reclamation of desert land to continuous cotton crop** affects soil properties and microbial communities in the desert-oasis ecotone of **njiang, China. J Soils Sediments 20:862–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02469-2 Lu RK (1999) Soil and agro-chemical analysis methods. China Agricultural Science and Technology Press, Bei**g Lu J, Qiu KC, Li WX, Wu Y, Ti JS, Chen F, Wen XY (2019) Tillage systems influence the abundance and composition of autotrophic CO2-fixing bacteria in wheat soils in North China. Eur J Soil Biol 93:103086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2019.103086 Luneberg K, Schneider D, Siebe C, Daniel R (2018) Drylands soil bacterial community is affected by land use change and different irrigation practices in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico. Sci Rep 8:1413. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19743-x Maron PA, Sarr A, Kaisermann A, Leveque J, Mathieu O, Guigue J, Karimi B, Bernard L, Dequiedt S, Terrat S, Chabbi A, Ranjard L (2018) High microbial diversity promotes soil ecosystem functioning. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e02738-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02738-17 Mendes R, Kruijt M, Bruijn DI, Dekkers E, Voort MVD, Schneider JHM, Piceno YM, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Bakker PAHM, Raaijmakers JM (2011) Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science 332:1097–1100. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1203980 Miao RH, Liu YZ, Wu LQ, Wang D, Liu YC, Miao Y, Yang ZL, Guo MX, Ma J (2022) Effects of long-term grazing exclusion on plant and soil properties vary with position in dune systems in the Horqin Sandy Land. Catena 209:105860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.105860 Navarrete AA, Kuramae EE, de Hollander M, Pijl AS, van Veen JA, Tsai SM (2013) Acidobacterial community responses to agricultural management of soybean in Amazon forest soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 83:607–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/1574-6941.12018 Okolo CC, Gebresamuel G, Zenebe A, Haile M, Eze PN (2020) Accumulation of organic carbon in various soil aggregate sizes under different land use systems in a semi-arid environment. Agric Ecosyst Environ 297:106924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.106924 Qiao N, Xu XL, Cao GM, Ouyang H, Kuzyakov Y (2015) Land use change decreases soil carbon stocks in Tibetan grasslands. Plant Soil 395:231–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2556-8 Ren CJ, Liu WC, Zhao FZ, Zhong ZK, Deng J, Han XH, Yang GH, Feng YZ, Ren GX (2019) Soil bacterial and fungal diversity and compositions respond differently to forest development. Catena 181:104071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2019.104071 Rozema J, Flowers T (2008) Crops for a salinized world. Science 322:1478–1479. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1168572 Sarathchandra SU, Ghani A, Yeates GW, Burch G, Cox NR (2001) Effect of nitrogen and phosphate fertilisers on microbial and nematode diversity in pasture soils. Soil Biol Biochem 33:953–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00245-5 Schmidt SK, Nemergut DR, Darcy JL, Lynch R (2014) Do bacterial and fungal communities assemble differently during primary succession? Mol Ecol 23:254–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12589 Six J, Elliott TE, Paustian K, Doran JW (1998) Aggregation and soil organic matter accumulation in cultivated and native grassland soils. Soil Sci Soc Am J 62:1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1998.03615995006200050032x Szoboszlay M, Dohrmann AB, Poeplau C, Don A, Tebbe CC (2017) Impact of land-use change and soil organic carbon quality on microbial diversity in soils across Europe. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 93:146. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fix146 Tang J, Davy AJ, Jiang DM, Musa A, Wu DF, Wang YC, Miao CP (2016) Effects of excluding grazing on the vegetation and soils of degraded sparse-elm grassland in the Horqin Sandy Land, China. Agric Ecosyst Environ 235:340–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2016.11.005 Tang SM, Guo JX, Li SC, Li JH, **e S, Zhai XJ, Wang CJ, Zhang YJ, Wang K (2019) Synthesis of soil carbon losses in response to conversion of grassland to agriculture land. Soil Tillage Res 185:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.08.011 Tang J, Yin JZ, Davy AJ, Pan FF, Han X, Huang SN, Wu DF (2022) Biogas slurry as an alternative to chemical fertilizer: changes in soil properties and microbial communities of fluvo-aquic soil in the North China Plain. Sustainability 14:15099. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215099 Wang Q, Zhang L, Li L, Bai YH, Cao J, Han XG (2010a) Changes in carbon and nitrogen of Chernozem soil along a cultivation chronosequence in a semi-arid grassland. Eur J Soil Sci 60:916–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.2009.01174.x Wang Y, Xu J, Shen JH, Luo YM, Scheu S, Ke X (2010b) Tillage, residue burning and crop rotation alter soil fungal community and water-stable aggregation in arable fields. Soil Tillage Res 107:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2010.02.008 Wang F, Liang YT, Jiang YJ, Yang YF, Xue K, **ong JB, Zhou JZ, Sun B (2015) Planting increases the abundance and structure complexity of soil core functional genes relevant to carbon and nitrogen cycling. Sci Rep 5:14345. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14345 Wang ZR, Liu YB, Zhao LN, Zhang WL, Liu LC (2019) Change of soil microbial community under long-term fertilization in a reclaimed sandy agricultural ecosystem. PeerJ 7:e6497. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6497 Wang C, Li LH, Yan YC, Cai YR, Xu DW, Wang X, Chen JQ, **n XP (2021) Effects of cultivation and agricultural abandonment on soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in a meadow steppe in eastern Inner Mongolia. Agric Ecosyst Environ 309:107284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2020.107284 Whalen JK, Willms WD, Dormaar JF (2003) Soil carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in modified rangeland communities. J Range Manage 56:665–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/4003944 White R, Murray S, Rohweder M, Prince S, Thompson K (2000) Pilot analysis of global systems: Grassland Ecosystems. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC Xu N, Tan GC, Wang HY, Gai XP (2016) Effect of biochar additions to soil on nitrogen leaching, microbial biomass and bacterial community structure. Eur J Soil Biol 74:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.02.004 Yang Y, Shi Y, Sun WJ, Chang JF, Zhu JX, Chen LY, Wang X, Guo YP, Zhang HT, Yu LF, Zhao SQ, Xu K, Zhu JL, Sheng HH, Wang YY, Peng YF, Zhao X, Wang XP, Hu HF, Chen SP, Huang M, Wei XF, Wang SP, Zhu B, Niu SL, Tang ZY, Liu LL, Fang YT (2022) Terrestrial carbon sinks in China and around the world and their contribution to carbon neutrality. Sci China Life Sci 65:861–895. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11427-021-2045-5 Zhang L, Xue TT, Yuan L, Gao FF, Hao XY, Yang CL, Wang L, Han YL, Li H, Wang H (2022) The effect of vineyard reclamation on soil properties and microbial communities in desertified land in Hongsibu, Ningxia. Catena 211:106002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2021.106002 Zhao L, Xu H, Liu JH, Li H, Men J, Yang XS (2020) Changes in soil properties and crop yields of farmland over a 20-year reclamation period from grassland in the hilly areas of Hebei, China. Arch Agron Soil Sci 67:594–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/03650340.2020.1741552 Zhou J, Jiang X, Zhou BK, Zhao BS, Ma MC, Guan DW, Li J, Chen SF, Cao FM, Shen DL, Qin J (2016) Thirty four years of nitrogen fertilization decreases fungal diversity and alters fungal community composition in black soil in northeast China. Soil Biol Biochem 95:135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.12.012 Zucca C, Canu A, Previtali F (2010) Soil degradation by land use change in an agropastoral area in Sardinia (Italy). Catena 83:46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2010.07.003 Special thanks are given to Yongming Luo, Hongmei Wang for their valuable help in field soil sampling. Sequencing service was provided by Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd Shanghai, China. This research was supported by Key Project of Chinese National Programs for Research and Development (2016YFC0500803) and Foundation of Scientific Research of Henan Institute of Science and Technology (208010617009). JT and FP analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. JY collected soil samples and ADJ revised the original draft. RM and XH conducted the experiment, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Not applicable. Not applicable. The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. : Table S1. Mean abundances of measured soil bacterial communities at phylum level in response to different periods of continuous cultivation. : Table S2. Mean abundances of measured soil fungal communities at phylum level in response to different periods of continuous cultivation. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Tang, J., Yin, J., Davy, A.J. et al. Changes in soil fertility and microbial communities following cultivation of native grassland in Horqin Sandy Land, China: a 60-year chronosequence.

Ecol Process 12, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-023-00431-2 Received: Accepted: Published: DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-023-00431-2Materials and methods

Research site and soil sampling

Measurements of soil characteristics

Soil DNA extraction and microbial high-throughput sequencing

Statistical analysis

Results

Changes in soil properties after cultivation

Changes in microbial community after cultivation

Relationships between soil properties and microbial characteristics

Discussion

Soil properties in response to grassland conversion

Implications of grassland reclamation in traditional pastoral regions

Availability of data and materials

References

Acknowledgements

Funding

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Competing interests

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

Additional file 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keywords