Abstract

In this study, we manifest a new class of map**s that satisfy Geraghty–Ćirić-type contractive conditions in the context of b-metric spaces and prove a theorem on the existence and uniqueness of fixed points. Our results unify and generalize the results of Geraghty; Ćirić; Dukic, Kadelburg, and Radenović; and Shu-fang Li, Fei Hi, and Ning Lu in the setting of b-metric spaces. Furthermore, we provide examples to verify the correctness and applicability of our results. We also utilize our findings to show the existence of a unique solution for a nonlinear integral equation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and preliminaries

Fixed point theory is one of the fundamental and most significant areas in the advancement of mathematics and nonlinear analysis. This theory has been used extensively in numerous scientific disciplines, including computer science, engineering, chemistry, biology, economics, medical sciences, and telecommunication. One of the key findings of traditional functional analysis, known as the Banach contraction principle, was initially presented by Banach [9] in 1922. This principle is a well-known and widely recognized result of fixed point theory. Since its initial proposal and successful demonstration, numerous mathematicians have extended and generalized the Banach contraction map** concept in several intriguing ways.

Geraghty [18] demonstrated a significant extension of the Banach contraction principle in 1973 by using an auxiliary function instead of a constant and establishing a fixed point result for these map**s in the setting of complete metric spaces. Geraghty [18] stated and proved the following result:

Theorem 1

([18])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d)\) be a complete metric space and \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a map** satisfying

for all \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\), where \(\beta \in \mathcal{S} = \{ \beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,1) | \lim_{n \to \infty} \beta (\zeta _{n}) = 1 \implies \lim_{n \to \infty} \zeta _{n} = 0 \}\). Then, \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*}\) in \(\mathcal{M}\).

Later on, many researchers have generalized and extended the result obtained by Geraghty in diverse ways, see [4, 5, 7, 14, 15, 17, 19] and the references therein.

Ćirić [10, 11] established the famous Ćirić-type fixed point theorem in the context of metric spaces, which is regarded as one of the most well-known findings that generalizes the Banach contraction principle. An important generalization of the Banach contraction principle obtained by Ćirić is as follows:

Theorem 2

([11])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d)\) be a complete metric space and \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a map**. If there exists a \(\lambda \in [0,1)\) satisfying

for all \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\), then \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*}\) in \(\mathcal{M}\).

Over the past few decades, fixed point theorems of the Ćirić kind have been generalized and extended in various ways by several authors. In 2013, Kumam et al. [23] reported one of the most interesting results and established a new fixed point theorem, which is a generalization of the Ćirić fixed point theorem. Karapınar [21] explored a Ćirić-type nonunique fixed point result in the framework of Branciari metric spaces and generalized the Ćirić-type fixed point theorem.

Recently, some authors studied fixed point theorems that incorporate Geraghty and Ćirić type contraction conditions in the framework of complete metric spaces. In 2019, Alqahtani et al. [2] introduced the notion of Ćirić-type φ-Geraghty contraction map**s and investigated under which conditions such map**s possess a unique fixed point in complete metric spaces.

In 2022, Shu-fang Li et al. [25] unified Geraghty and Ćirić type contractive map**s and obtained a fixed point for such map**s in a complete metric space. Shu-fang Li et al. [25] defined Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction as follows:

A self-map \(\mathcal{T}\) on a metric space \((\mathcal{M},d)\) is said to be a Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map** if there exists \(\beta \in \mathcal{S}\) such that, for all \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\),

where

Theorem 3

([25])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d)\) be a complete metric space and \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction with some \(\beta \in \mathcal{S}\). Then \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*} \in \mathcal{M}\).

Notation 1

Throughout the paper, we use the following notations:

-

(i)

ℜ stands for the set of all real numbers;

-

(ii)

\(\Re ^{+}\) stands for the set of all nonnegative real numbers;

-

(iii)

\(\mathbb{N}\) stands for the set of all positive integers;

-

(iv)

\(\mathbb{N}_{0}\) stands for the set of all nonnegative integers;

-

(v)

\(\mathcal{M}\) and \(\mathcal{T}\) denote a nonempty set and a self-map** on \(\mathcal{M}\), respectively.

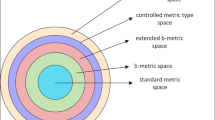

The notion of a b-metric space was introduced by Bakhtin [8] and Czerwik [12] as a generalization of metric space, and they demonstrated fixed point results for contractive map**s in such spaces. Subsequently, several papers on the fixed point theory for different classes of map**s satisfying various contractive conditions have been published in b-metric spaces. Karapinar et al. [22] obtained a fixed point theorem of Ćirić type in b-metric spaces. In 2016, Pant and Panicker [27] introduced Geraghty and Ćirić type fixed point theorems and obtained fixed point results for admissible map**s in the setting of b-metric spaces. In 2019, Mlaiki et al. [26] discussed the fixed point results given by Pant and Panicker [27] and improved some related fixed point theorems in b-metric spaces. For some recent significant developments in the area of b-metric spaces and their extensions with various contractive conditions, we refer to the work of Karapinar [20], Afshari et al. [1], Ding et al. [13], Latif et al. [24], Faraji et al. [17], Eshraghi et al. [16], Amirbostagi and Asad [3], Asadi and Afshar [6], Erhan [15], and the references therein.

The concept of a b-metric space was defined independently by Bakhtin [8] and Czerwik [12] as follows:

Definition 1

A map** \(d : \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) is said to be a b-metric if it satisfies the following three conditions:

-

(i)

\(d(x,y)=0\) if and only if \(x=y\) for any \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\);

-

(ii)

\(d(x,y)=d(y,x)\) for any \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\);

-

(iii)

there exists a real number \(\nu \geq 1\) such that \(d(x,y) \leq \nu [d(x,z)+d(z,y)]\) for any \(x, y, z \in \mathcal{M}\).

In this case, the triplet \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) is called a b-metric space.

Remark 1

([1])

Every metric is a b-metric with \(\nu = 1\) but not conversely. Thus, the class of b-metrics is effectively larger than that of metrics.

We illustrate the above remark by using the following two examples.

Example 1

([1])

Let \(\mathcal{M} = [0, 1]\) be a set and \(d : \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) be a function given by \(d(x,y)=|x-y|^{2}\) for all \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\). For any \(x, y, z \in \mathcal{M}\), we have

So, d is a b-metric with \(\nu = 2\). But d is not a metric. In fact, if we take \(x = 0\) and \(y = 1\), we obtain

Example 2

([20])

Given a set \(\mathcal{M} = \{ 0, 1, 2 \}\). Define the function \(d : \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) by

Letting \(x = 2\) and \(y = 0\), we get

However, for all \(x, y, z \in \mathcal{M}\), we have

Therefore, d is a b-metric with \(\nu = \frac{3}{2}\) but not a metric.

Definition 2

([12])

Let \(\{ x_{n} \}\) be a sequence on a b-metric space \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) with \(\nu \geq 1\). Then

-

(i)

\(\{ x_{n} \}\) is called b-convergent if there exists \(x \in \mathcal{M}\) such that \(d(x_{n},x) \to 0\) as \(n \to \infty \). In this case, we write \(\lim_{n \to \infty} x_{n} = x\).

-

(ii)

\(\{ x_{n} \}\) is called b-Cauchy if and only if \(\lim_{n, m \to \infty} d(x_{n},x_{m}) = 0\), that is, if for every \(\epsilon > 0\) there exists \(n_{0} \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(d(x_{n},x_{m}) < \epsilon \) for all \(n, m \geq n_{0}\).

Definition 3

([12])

A b-metric space \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) with \(\nu \geq 1\) is said to be complete if every Cauchy sequence in \(\mathcal{M}\) is b-convergent in \(\mathcal{M}\).

Remark 2

([12])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and \(\{ x_{n} \}\) is a b-convergent sequence in \(\mathcal{M}\). Then, the sequence \(\{ x_{n} \}\) has a unique limit and it is b-Cauchy.

In 2011, Dukic et al. [14] obtained fixed points for Geraghty-type map**s in b-metric spaces by considering the class of functions

where \(\nu \geq 1\). For instance, the function \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{\nu})\) defined by \(\beta (\zeta )=\frac{1}{\nu}e^{-\zeta}\) for \(\zeta > 0\) and \(\beta (0) \in [0,\frac{1}{\nu})\) is in \(\mathcal{S}_{\nu}\).

Theorem 4

([14])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a complete b-metric space with \(\nu > 1\). Suppose that a map** \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) satisfies

for all \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\) and for some \(\beta \in \mathcal{S}_{\nu}\). Then \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*} \in \mathcal{M}\).

In 2019, Faraji et al. [17] established a fixed point theorem satisfying Geraghty-type contractive conditions in b-metric spaces by defining a class of function \(\mathcal{S}_{\nu}^{*}\), for \(\nu \geq 1\), as

Theorem 5

([17])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a b-complete b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and let \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a self-map**. If there exists \(\beta \in \mathcal{S}_{\nu}^{*}\) such that

where

then \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point.

The aim of this paper is to introduce a new class of map**s satisfying Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction condition in the context of b-metric spaces and prove a theorem on the existence and uniqueness of fixed points for the map**s introduced. Our result generalize, include, and unify the results defined by Geraghty [18], Ćirić [11], Dukic et al. [14] and Shu-fang Li et al. [25], and also various existing results on the topic in the corresponding literature. Furthermore, we provide examples to illustrate the validity of our main result and apply our findings in establishing the existence and uniqueness of a solution of a nonlinear integral equation.

The following lemma is useful in proving our main result.

Lemma 1

([24])

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and let \(\{ x_{n} \}\) and \(\{ y_{n}\}\) be b-convergent to \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\), respectively. Then, the following inequality holds:

In particular, if \(x=y\), we have \(\lim_{n \to \infty}d(x_{n}, y_{n}) = 0\). Moreover, for each \(z \in \mathcal{M}\), we have

2 Main results

In this section, we introduce Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map**s and study fixed point results for such map**s in the setting of b-metric spaces.

Here, we use a comparison function \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{\nu})\), where \(\nu \geq 1\), satisfying the condition

We denote the set of all functions β satisfying the above condition by \(\mathcal{F}\).

The main result in this paper is based on the following contractive condition.

Definition 4

A map** \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) on a b-metric space \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) with \(\nu \geq 1\) is called a Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map** if there exists \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\) such that

where

Lemma 2

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and let \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a self-map**. Let \(x_{0} \in \mathcal{M}\) be given and \(\{ x_{n} \}\) be a sequence in \(\mathcal{M}\) such that \(x_{n} = \mathcal{T}x_{n-1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Consider the sequence defined by

for \(n \in \mathbb{N}_{0}\). If \(\mathcal{T}\) satisfies the contractivity condition in (1), then \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is bounded.

Proof

Let \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) be arbitrary and fixed. Then, for any \(p, q \in \mathbb{N}\) with \(1 \leq p,q \leq n\), using (1), we have

As a result, \(\max \{ d(x_{p},x_{q}) | 1 \leq p, q \leq n; p, q \in \mathbb{N}_{0} \} < A_{n}\). From this, we conclude that there is \(\omega _{n} \in \mathbb{N}\) with \(1 \leq \omega _{n} \leq n\) such that

Observe that \(0 \leq A_{n} \leq A_{n+1}\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}_{0}\). We aim to show that the sequence \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is bounded. Assume, to the contrary, that \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is unbounded. Then, since \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is an increasing sequence of nonnegative real numbers, we have \(\lim_{n \to \infty} A_{n} = +\infty \).

Now, applying b-triangle inequality on the term \(d(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n}})\) and using (1), we get

where

Since the sequences

are real-number sequences, there is a subsequence \(\{ \mathcal{L}(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n_{k} - 1}}) \}\) of \(\{ \mathcal{L}(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n - 1}}) \}\) that is equal to one of the following five terms:

So, we have five cases to consider:

Case 1. Suppose that

Rearranging the terms in the second inequality of (5) yields

Since \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \), we can see that \(\lim_{k \to \infty} ( \frac{1}{\nu}- \frac{d(x_{0},x_{1})}{A_{n_{k}}} ) = \frac{1}{\nu}\). Hence \(\limsup_{k \to \infty} \beta (d(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n_{k} - 1}})) = \frac{1}{\nu}\). This implies that \(\lim_{k \to \infty}d(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n_{k} - 1}}) = 0\) since \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\). Taking the limit on both sides of (5), we obtain

This contradicts our assumption \(\lim_{k \to \infty} A_{n_{k}} = + \infty \).

Case 2. Suppose that

By means of (3) and (6), we have

This contradicts \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \).

Case 3. Suppose that

Combining (3) and (7), we obtain

It follows from the second inequality in (8) that

As \(k \to +\infty \), we have \(( \frac{1}{\nu}-\frac{d(x_{0},x_{1})}{A_{n_{k}}} ) \to \frac{1}{\nu}\) and hence \(\beta (d(x_{\omega _{n_{k} - 1}},x_{\omega _{n_{k}}})) \to \frac{1}{\nu}\). Since \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\), we obtain \(\lim_{k \to \infty} d(x_{\omega _{n_{k} - 1}},x_{\omega _{n_{k}}}) = 0\). Letting \(k \to \infty \) on both sides of the inequality in (8), we get

This contradicts our assumption \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \).

Case 4. Suppose that

Substituting (9) into (3), we get

From the second inequality in (10) it follows that

Since \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \), then \(\lim_{k \to \infty} ( \frac{1}{\nu}- \frac{d(x_{0},x_{1})}{A_{n_{k}}} ) = \frac{1}{\nu}\) and hence \(\limsup_{k \to \infty}\beta (d(x_{0}, x_{\omega _{n_{k}}})) = \frac{1}{\nu}\). Since \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\), we have \(\lim_{k \to \infty} d(x_{0},x_{\omega _{n_{k}}}) = 0\). Letting \(k \to \infty \) in (10), we obtain

This contradicts \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \).

Case 5. Suppose that

Putting (11) into (3), we have

The second inequality in (12) yields that

Following similar argument as in case 4, we have that \(d(x_{1},x_{\omega _{n_{k - 1}}}) \to 0\) as \(k \to \infty \) and using (12), we obtain

This contradicts our assumption \(A_{n_{k}} \to +\infty \) as \(k \to \infty \).

The contradictions in all the cases considered above guarantee that \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is a bounded sequence. □

Theorem 6

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a complete b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and let \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a map** satisfying Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction condition in (1). Then, \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*} \in \mathcal{M}\).

Proof

Let \(x_{0} \in \mathcal{M}\) be arbitrary. Construct a sequence \(\{ x_{n} \}\) in \(\mathcal{M}\) by

Step 1. We show that \(\{ x_{n} \}_{n \in \mathbb{N}_{0}}\) is a b-Cauchy sequence in \(\mathcal{M}\). Consider a sequence defined by

Using Lemma 2, there exists \(K > 0\) such that \(A_{n} \leq K\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Since \(\{ A_{n} \}\) is an increasing sequence, we have \(\lim_{n \to \infty} A_{n} \leq K\).

Define a sequence \(\{ \varUpsilon _{n} \}\) on a b-metric space \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) by

From this, we can see that

Thus, \(\{ \varUpsilon _{n} \}\) is a decreasing and bounded sequence of nonnegative real numbers, so that it converges to some \(r \geq 0\), that is, \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \varUpsilon _{n} =r\). Then there exist two subsequences \(\{ x_{p_{k}} \}\) and \(\{ x_{q_{k}} \}\) of \(\{ x_{n} \}\) with \(q_{k} > p_{k} \geq k\) for \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) such that

We claim that \(r = 0\). Assume that \(r > 0\). Putting \(x = x_{p_{k} - 1}\) and \(y = x_{q_{k} - 1}\) in (1), we have

where

Thus, \(\mathcal{L}(x_{p_{k} - 1},x_{q_{k} - 1}) \) equals to one of the five terms on the right-hand side, so that we have five cases to consider.

First, consider the case \(\mathcal{L}(x_{p_{k} - 1},x_{q_{k} - 1}) = \beta (d(x_{p_{k} - 1},x_{q_{k} - 1}))d(x_{p_{k} - 1},x_{q_{k} - 1})\) for all \(k \in \mathbb{N}\). Then, condition (14) becomes

Taking the upper limit as \(k \to \infty \) on both sides of (15), it follows that

and, using (13), we have

Since \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\), we have \(\lim_{k \to \infty} d(x_{p_{k} - 1},x_{q_{k} - 1}) = 0\). Using (13) and the first inequality of (15), we get

This contradicts our assumption \(r >0\). Hence, \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \varUpsilon _{n} =r=0\).

The other four cases can be handled similarly. Therefore, we have \(r = \lim_{n \to \infty} \varUpsilon _{n} = 0\).

Now, let \(m, n \in \mathbb{N}_{0}\) with \(m > n\). Then we get

Hence, \(\{ x_{n} \}\) is a b-Cauchy sequence in \(\mathcal{M}\). By completeness of \(\mathcal{M}\), the sequence \(\{x_{n}\}\) converges to some \(x^{*} \in \mathcal{M}\).

Step 2. We show that \(x^{*}\) is a fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\).

Assume that \(\mathcal{T}x^{*} \neq x^{*}\), that is, \(d(\mathcal{T}x^{*}, x^{*})>0\). Letting \(x = x_{n}\) and \(y = x^{*}\) in (1), we have

where

We consider the following five cases:

Case 1. Suppose that \(\mathcal{L}(x_{n},x^{*})= \beta (d(x_{n},x^{*}))d(x_{n},x^{*})\). Then, from (16), we have

Taking the upper limit as \(n \to \infty \) on both sides of the above inequality together with Lemma 1 and noting that \(\lim_{n \to \infty} d(x_{n},x^{*}) = 0\), we have

Consequently, we get \(d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*})= 0\). This contradicts our assumption \(d(\mathcal{T}x^{*}, x^{*}) > 0\).

Case 2. Suppose that \(\mathcal{L}(x_{n},x^{*})= \beta (d(x_{n},x_{n+1})) d(x_{n},x_{n+1})\). In a similar way as above, using (16) and Lemma 1 together with \(\lim_{n \to \infty} d(x_{n},x_{n+1}) = 0\), we have

This implies \(d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*})= 0\), contradicting our assumption \(d(\mathcal{T}x^{*}, x^{*}) > 0\).

Case 3. Suppose that \(\mathcal{L}(x_{n},x^{*})= \beta (d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*}))d(x^{*}, \mathcal{T}x^{*})\). Then, using (16) and Lemma 1, we have

which is a contradiction.

Case 4. Suppose that \(\mathcal{L}(x_{n},x^{*})= \beta (d(x_{n},\mathcal{T}x^{*}))d(x_{n}, \mathcal{T}x^{*})\). Then, using (16), we have

Applying b-triangle inequality on \(d(x_{n},Tx^{*})\), we have

which is equivalent to

Taking the upper limit as \(n \to \infty \) on both sides of the above inequality, we obtain

That is,

Using Lemma 1, we have \(0 < \frac{1}{\nu} d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*}) \leq \limsup_{n \to \infty} d(x_{n+1},\mathcal{T}x^{*}) \leq \nu d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*})\), so that

From this, it follows that

Since \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\), we get \(\lim_{n \to \infty} d(x_{n},\mathcal{T}x^{*}) = 0\). That is, \(\lim_{n \to \infty} x_{n} = \mathcal{T}x^{*}\). By the uniqueness of limit of a b-convergent sequence, we have \(x^{*} = \mathcal{T}x^{*}\). This contradicts our assumption \(x^{*}\neq \mathcal{T}x^{*}\).

Case 5. Suppose that \(\mathcal{L}(x_{n},x^{*})= \beta (d(x^{*},x_{n+1}))d(x^{*},x_{n+1})\). Similarly, using (16) and Lemma 1 together with \(\lim_{n \to \infty} d(x^{*},x_{n+1}) = 0\), we have

This implies \(d(x^{*},\mathcal{T}x^{*})= 0\) and it contradicts the assumption \(d(\mathcal{T}x^{*}, x^{*}) > 0\).

Therefore, from cases 1 to 5, we deduce that \(x^{*} = \mathcal{T}x^{*}\) and hence \(x^{*}\) is a fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\).

Step 3. Now, we show the uniqueness of the fixed point.

Assume \(u \in \mathcal{M}\) is another fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) such that \(x^{*} \neq u\) (or \(d(x^{*},u) >0\)). Then, by means of (1), we get

which is a contradiction. Therefore, \(x^{*}=u\) and hence \(x^{*}\) is the only fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) in \(\mathcal{M}\). □

The following corollary is an immediate consequence of Theorem 6.

Corollary 1

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a complete b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\). Suppose \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) is a self-map** and \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\) satisfies the following condition for any \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\):

where \(\mathcal{N}(x,y) = \max \{ d(x,y),d(x,\mathcal{T}x),d(y,\mathcal{T}y),d(x, \mathcal{T}y),d(y,\mathcal{T}x) \}\). Then \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point \(x^{*} \in \mathcal{M}\).

Proof

For any \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\), the value of \(\mathcal{N}(x,y)\) is always equal to at least one of the terms \(d(x,y)\), \(d(x,\mathcal{T}x)\), \(d(y,\mathcal{T}y)\), \(d(x,\mathcal{T}y)\), or \(d(y,\mathcal{T}x)\). It follows that

All the assumptions of Theorem 6 are satisfied, and we deduce that \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point in \(\mathcal{M}\). □

Remark 3

Let \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) be a complete b-metric space with \(\nu \geq 1\) and let \(\mathcal{T}: \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) be a self-map**. Since \(\beta (d(x,y))d(x,y) \leq \mathcal{L}(x,y)\) for all \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\), then we conclude that Theorem 4 is a special case of Theorem 6.

The following example illustrates the validity of our result in Theorem 6.

Example 3

Let \(\mathcal{M} = \{ 1,\frac{1}{2},\frac{1}{3}, \dots \} \cup \{ 0 \}\) and let the function \(d: \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) be defined by

Define the map**s \(\mathcal{T} : \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) and \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{\nu})\), respectively, by

where \(\Gamma =\{ \frac{\kappa}{\omega}| \text{ for some } \kappa , \omega \in \mathbb{N}, \kappa \text{ is odd}, \gcd(\kappa , \omega )=1 \}\).

We show that all the conditions of Theorem 6 are fulfilled to conclude the existence of a unique fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\), whereas condition (17) in Corollary 1 is not with the \(\beta (\zeta )\).

Proof

Clearly, d is a b-metric with \(\nu = 2\) and hence \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) is a complete b-metric space. Also, \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\).

To show that the conditions in Theorem 6 are satisfied, it is sufficient to prove that (1) holds with β.

In case of \(x = y\) for any \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\), from (1) we have \(d(\mathcal{T}x,\mathcal{T}y)=0 \leq L(x,y)\), so that all the conditions in Theorem 6 are satisfied.

Thus, we suppose that \(x \neq y\). Without loss of generality, assume that \(x > y\). Now, we consider the following two cases:

Case 1. Suppose \(y=0\). Let \(x=\frac{1}{a}\), for some \(a \in \mathbb{N}\). Then,

Case 2. Suppose \(x = \frac{1}{a}\) and \(y =\frac{1}{b}\) for some \(a, b \in \mathbb{N}\). Since \(x > y\), then \(b > a\).

Here we consider the following two subcases:

Case 2.1. Suppose a is odd and b is even, or vice versa. In this case, \(b-a\) is odd. Then,

and since \((b-a)^{2}\) is odd, we have

Now, using the values of \(d(x,y)\) and \(\beta (d(x,y))\) obtained above, we have

Case 2.2. Suppose both a and b are even (or odd). In both cases, \(b^{2}+1-a\) is odd. Then,

and

Observe that, since \(b > a\), we have \((b^{2}-a^{2})^{2} \leq (b^{2} + 1 - a)^{2}\) and \((a^{2} + 1)^{2} \geq 2a^{2} + 1\).

Thus,

Therefore, from cases 1 and 2 all the conditions of Theorem 6 are satisfied and \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point in \(\mathcal{M}\). Thus, 0 is the only fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) in \(\mathcal{M}\).

To show that condition (17) of Corollary 1 fails with this β, let us take \(x=\frac{1}{j+1}\) and \(y=\frac{1}{j+2}\), for \(j \in \mathbb{N}_{0}\). Then,

Since \(j^{2}+3j+4\) is even for all \(j \in \mathbb{N}_{0}\), from the definition of β, we obtain

Thus,

In particular, if \(x=\frac{1}{2}\) and \(y=\frac{1}{3}\), then

From the definition of β, we obtain

Thus,

Therefore, from this example we can see that condition (17) of Corollary 1 is not satisfied with the \(\beta (\zeta )\) and hence Corollary 1 is not applicable to show the existence and uniqueness of the fixed point. □

The following example indicate that our result is an actual generalization of Theorem 4.

Example 4

Let \(\mathcal{M} = \{ x_{1},x_{2},x_{3},x_{4} \}\). Define \(d: \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) by

Clearly, \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) is a complete b-metric space with \(\nu = \frac{4}{3}>1\). Define a map** \(\mathcal{T} : \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) by

and define a function \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{\nu})\) by \(\beta (\zeta ) = \frac{1}{\nu +\zeta}\) for \(\zeta >0\) and \(\beta (0) = 0\).

We show that all the conditions of Theorem 6 are satisfied and conclude that \(x = x_{1}\) is the unique fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\), but the conditions in Theorem 4 are not satisfied.

Proof

As \(d(x_{2},x_{4}) = 1 > \frac{3}{4} = \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{2} = d(x_{2},x_{1})+d(x_{1},x_{4})\), the function d is not a metric on \(\mathcal{M}\).

The condition in Theorem 4 is fulfilled if, with the \(\beta \in \mathcal{F,}\) the inequality

holds. Since \(\beta (\zeta )< \frac{1}{\nu}\) for \(\zeta > 0\), we have \(d(\mathcal{T}x,\mathcal{T}y) < d(x,y)\) for all \(x, y \in \mathcal{M}\). Let us take \(x = x_{1}\) and \(y = x_{3}\). Then, we have

and this contradicts \(d(\mathcal{T}x_{1},\mathcal{T}x_{3}) \leq \beta (d(x_{1},x_{3})) d(x_{1},x_{3})\). So, the inequality in (18) does not hold for all \(x_{i}, x_{j} \in \mathcal{M}\), and hence Theorem 4 is not applicable to conclude the existence of fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) with the \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\).

On the other hand, for all \(x_{i},x_{j} \in X\), where \(i,j=1,2,3,4\),

To see this, observe that

Thus,

Therefore, all the conditions of Theorem 6 and Corollary 1 are satisfied with the β defined above and \(x_{1}\) is the only fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\). □

3 Applications to nonlinear integral equations

In this section, we discuss an existence result for the solution to a nonlinear integral equation using Theorem 6. We developed this application inspired by [17].

Let \(\mathcal{M} = C[\alpha ,\gamma ]\) be the set of all continuous real-valued functions defined on \([\alpha ,\gamma ]\), where \(0 \leq \alpha < \gamma \). Let \(d: \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) be defined by

Clearly, \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) is a complete b-metric space with \(\nu = 2\).

Our aim is to find a function \(x(t) \in \mathcal{M}\), \(t \in [\alpha ,\gamma ]\), such that for \(f: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \to \Re \), \(g: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \times [\alpha , \gamma ] \to \Re\) and \(\mathcal{A}: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \times [ \alpha ,\gamma ] \times \Re \to \Re \), it satisfies the nonlinear integral equation

Theorem 7

The nonlinear integral equation (20) has a unique solution in \(\mathcal{M}\) provided that the following hypotheses hold:

-

(i)

the functions \(f: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \to \Re \), \(g: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \times [\alpha , \gamma ] \to \Re\) and \(\mathcal{A}: [\alpha ,\gamma ] \times [ \alpha ,\gamma ] \times \Re \to \Re \) are continuous on \([\alpha ,\gamma ]\), \([\alpha ,\gamma ]^{2}\), and \([\alpha ,\gamma ]^{2} \times \Re \), respectively.

-

(ii)

for all \(t,\tau \in [\alpha ,\gamma ]\) and for all \(x,y \in \mathcal{M}\), there exists \(\phi : \mathcal{M} \times \mathcal{M} \to \Re ^{+}\) such that

$$\begin{aligned} \bigl\vert \mathcal{A}\bigl(t,\tau ,x(\tau )\bigr)-\mathcal{A}(t,\tau ,y(\tau ) \bigr\vert \leq \phi (x, y) \sqrt{\ln \Bigl( 1 + \max_{\alpha \leq \tau \leq \gamma} \bigl\vert x(\tau )-y(\tau ) \bigr\vert ^{2} \Bigr)}. \end{aligned}$$ -

(iii)

for all \(t,\tau \in [\alpha ,\gamma ]\),

$$\begin{aligned} \max_{\alpha \leq t \leq \gamma} \int _{\alpha}^{\gamma} \bigl\vert g(t,\tau ) \phi (x, y) \bigr\vert ^{2} \,d\tau \leq \frac{1}{\nu (\gamma - \alpha )}. \end{aligned}$$

Proof

Define a map** \(\mathcal{T} : \mathcal{M} \to \mathcal{M}\) by

The existence of a unique solution of the nonlinear integral equation (20) is equivalent to the existence of a fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) in (21).

Now, we prove that \(\mathcal{T}\) is a Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map**. From conditions (ii) and (iii), we have

Then, by (19),

Define \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{2})\) by \(\beta (\zeta )=\frac{\ln (1+\zeta )}{2\zeta}\) for \(\zeta > 0\) and \(\beta (0) \in [0,\frac{1}{2})\). Then, \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\) and

Thus, for all \(t \in [\alpha ,\gamma ]\) and for all \(x,y \in C[\alpha ,\gamma ]\), we have \(d(\mathcal{T}x,\mathcal{T}y) \leq \mathcal{L}(x,y)\). Hence, \(\mathcal{T}\) is a Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map** with \(\beta (\zeta )=\frac{\ln (1+\zeta )}{2\zeta}\) for \(\zeta > 0\) and \(\beta (0) \in [0, \frac{1}{2})\).

Therefore, by Theorem 6, \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point in \(\mathcal{M} = C[\alpha ,\gamma ]\). Hence, the nonlinear integral equation (20) has a unique solution in \(\mathcal{M} = C[\alpha ,\gamma ]\). □

Example 5

Consider \(\mathcal{M} = C[0,1]\) the space of real-valued continuous functions on \([0,1]\). Assume that for any \(x \in \mathcal{M}\), we have \(x(t) > 0\) for all \(t \in [0,1]\). Let \(d: C[0,1] \times C[0,1] \to \Re ^{+}\) be a b-metric given by

for all \(x, y \in C[0,1]\). Consider a nonlinear integral equation

for \(x \in C[0,1]\). We show that, by using Theorem 6, the nonlinear integral equation (22) has a unique solution.

Proof

We can easily verify that \((\mathcal{M},d, \nu )\) is a b-metric space with \(\nu = 2\). Define \(\mathcal{T} : C[0,1] \to C[0,1]\) by

for \(x \in C[0,1]\). The existence of a unique fixed point of \(\mathcal{T}\) in (23) is equivalent to the existence of a unique solution of the nonlinear integral equation (22).

Observe that (22) is a particular case of (20) with \(f(t)=\frac{1}{2}t\), \(g(t,\tau )=t \tau \) and \(\mathcal{A}(t,\tau ,x(\tau ))=\frac{e^{-t}x(\tau )}{1+x(\tau )}\). Also, the functions \(f(t)\) and \(g(t,\tau )\) are continuous on \([0,1]\), and \(\mathcal{A}(t,\tau ,x(\tau ))\) is integrable with respect to τ on \([0,1]\).

For every sequence \(\{ t_{n} \} \subset [0,1]\), we have \(t \in [0,1]\) such that \(\lim_{n \to \infty} t_{n} =t\). Then, for any \(x \in C[0,1]\), we get

Letting \(n \to \infty \), we have \(|\mathcal{T}x(t_{n})-\mathcal{T}x(t)| \to 0\). That is, \(\lim_{n \to \infty} \mathcal{T}x(t_{n}) = \mathcal{T}x(t)\). Hence, \(\mathcal{T}x \in C[0,1]\) for all \(x \in C[0,1]\). Then, for all \(t, \tau \in [0,1]\) and for all \(x, y \in C[0,1]\), we have

and

Let \(\phi (x, y) = 1\) for all \((x, y) \in C[0,1] \times C[0,1]\). Then

Define \(\beta : \Re ^{+} \to [0,\frac{1}{2})\) by \(\beta (\zeta )=\frac{\ln (1+\zeta )}{2\zeta}\) for \(\zeta > 0\) and \(\beta (0) \in [0,\frac{1}{2})\). Then \(\beta \in \mathcal{F}\). Thus,

Thus, for all \(t \in [0,1]\), we have \(d(\mathcal{T}x,\mathcal{T}y) \leq \mathcal{L}(x,y)\). Therefore, by Theorem 6, we see that \(\mathcal{T}\) has a unique fixed point in \(\mathcal{M} = C[0,1]\). Hence, the nonlinear integral equation (22) has unique solution in \(\mathcal{M} = C[0,1]\). □

4 Conclusion

In this manuscript, we introduced a new fixed point theorem for a self-map** satisfying Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction conditions in the framework of b-metric spaces. We established the existence and uniqueness of fixed points for such map**s. The presented main theorem unifies and generalizes some fixed point results in the related literature. We have provided an example to demonstrate the superiority of our results compared to some corresponding fixed point results. In addition, we presented the applicability of our primary finding to show the existence of a unique solution to a nonlinear integral equation.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Afshari, H., Aydi, H., Karapinar, E.: Existence of fixed points of set-valued map**s in b-metric spaces. East Asian Math. J. 32(3), 319–332 (2016)

Alqahtani, B., Fulga, A., Karapınar, E.: On Ćirić type φ-Geraghty contractions. Thai J. Math. 17(1), 205–216 (2019)

Amirbostaghi, G., Asadi, M.: m-Convex structure on b-metric spaces. Filomat 35(14), 4765–4776 (2021)

Arshad, M., Hussain, A.: Fixed point results for generalized rational α-Geraghty contraction. Miskolc Math. Notes 18(2), 611–621 (2017)

Arshad, M., Hussain, A., Azam, A.: Fixed point of α-Geraghty contraction with applications. UPB Bull. Sci. 78(2), 67–78 (2016)

Asadi, M., Afshar, M.: Fixed point theorems in the generalized rational type of C-class functions in b-metric spaces with application to integral equation. 3C Empresa. Invetig. Pensam. Crit. 11(2), 64–74 (2022)

Aydi, H., Karapinar, E., Erhan, I.M., Salimi, P.: Best proximity points of generalized almost ψ-Geraghty contractive non-self map**s. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2014, 32 (2014)

Bakhtin, I.A.: The contraction map** principle in almost metric space. Funct. Anal. Appl. 30, 26–37 (1989)

Banach, S.: Sur les operations dans les ensembles abstraits et leur applications aux equations integrales. Fundam. Math. 3, 133–181 (1922)

Ćirić, L.B.: Generalized contractions and fixed-point theorems. Publ. Inst. Math. 12(26), 19–26 (1971)

Ćirić, L.B.: A generalization of Banach’s contraction principle. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 45(2), 267–273 (1974)

Czerwik, S.: Contraction map**s in b-metric spaces. Acta Math. Inform. Univ. Ostrav. 1(1), 5–11 (1993)

Ding, H., Imdad, M., Radenović, S., Vujaković, J.: On some fixed point results in b-metric, rectangular and b-rectangular metric spaces. Arab J. Math. Sci. 22, 151–164 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajmsc.2015.05.003

Dukic, D., Kadelburg, Z., Radenović, S.: Fixed points of Geraghty-type map**s in various generalized metric spaces. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2011, Article ID 561245 (2011)

Erhan, I.M.: Geraghty type contraction map**s on Branciari b-metric spaces and applications. Adv. Theory Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 1(2), 147–160 (2017)

Eshraghi Samani, M., Vaezpour, S.M., Asadi, M.: New fixed point results with \(\alpha _{qs^{p}}\)-admissible contractions on b-Branciari metric spaces. J. Inequal. Spec. Funct. 9(4), 101–112 (2018)

Faraji, H., Savić, D., Radenović, S.: Fixed point theorems for Geraghty contraction type map**s in b-metric spaces and applications. Axioms 8(1), 34 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/axioms8010034

Geraghty, M.: On contractive map**s. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 40, 604–608 (1973)

Karapinar, E.: α–ψ-Geraghty contraction type map**s and some related fixed point results. Filomat 28(1), 37–46 (2014)

Karapinar, E.: A short survey on the recent fixed point results on b-metric spaces. Constr. Math. Anal. 1(1), 15–44 (2018)

Karapınar, E., Agarwal, R.P.: A note on Ćirić type non-unique fixed point theorems. Fixed Point Theory Appl. 2017, 20 (2017)

Karapinar, E., Mitrović, Z.D., Öztürk, A., Radenović, S.: On a theorem of Ćirić in b-metric spaces. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo 70, 217–225 (2021)

Kumam, P., Dung, N.V., Sitthithakerngkiet, K.: A generalization of Ćirić fixed point theorems. Filomat 29(7), 1549–1556 (2013)

Latif, A., Parvaneh, V., Salimi, P., Al-Mazrooei, A.E.: Various Suzuki type theorems in b-metric spaces. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 8(4), 363–377 (2015)

Li, S., Hi, F., Lu, N.: A unification of Geraghty type and Ćirić type fixed point theorems. Filomat 36(8), 2605–2616 (2022)

Mlaiki, N., Dedovic, N., Aydi, H., Gardašević-Filipović, M., Bin-Mohsin, B., Radenović, S.: Some new observations on Geraghty and Ćirić type results in b-metric spaces. Mathematics 7(7), 643 (2019)

Pant, R., Panicker, R.: Geraghty and Ćirić type fixed point theorems in b-metric spaces. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 9(11), 5741–5755 (2016)

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. and K.K. involved in conceptualization, methodology. K.K. contributed in supervision and editing the manuscript. A.G. and H.E. contributed in formal analysis. H.E. contributed in revising and proof reading of the manuscript. All authors contributed equally. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalo, A.G., Tola, K.K. & Yesuf, H.E. Fixed point results for Geraghty–Ćirić-type contraction map**s in b-metric space with applications. Fixed Point Theory Algorithms Sci Eng 2024, 8 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-024-00764-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13663-024-00764-3