Abstract

Objective

Cognitive reappraisal (CR), as an adaptive emotion regulation strategy, may play a role in transforming affect in a positive direction during or after exercise, thereby supporting physical activity (PA) adherence. The present study aimed to test the associations among PA, CR frequency, and affective response to PA, and further to examine the role of CR on PA behavior through affective response.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with a sample of 105 adults, 74 of whom were women, with a mean age of 25.91. Self-report scales were used to measure PA, CR, and affective response to PA. Along with scales, demographic questions on age, sex, and education level were included. Data was collected via an online questionnaire.

Results

The frequency of CR use was positively associated with affective response, and affective response with PA behavior. Mediation analysis revealed that affective response mediated the relationship between CR and PA.

Discussion

Results were in the expected direction demonstrating the mediating role of affective response between CR and PA which implies that PA adherence might be facilitated by CR engagement. PA intervention programs should consider implementing CR ability and use frequency improving techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical inactivity has become a major public health problem in the past decades and ranks as the fourth leading risk factor for mortality worldwide [1, 2]. While the relationship between physical activity (PA) and physical and mental health is well established [3, 4], the underlying psychological mechanisms contributing to formation and maintenance of PA habits and the factors associated with physical inactivity still need to be better understood.

As individuals may tend to repeat activities that create pleasure and tend to avoid activities associated with displeasure or pain, affective response to exercise seems to be an important factor for exercise adherence [5,6,7,8]. Previous studies have demonstrated that judging past exercise experiences as pleasant or unpleasant influences future PA [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, positive affective states at the end of the exercise might be beneficial for the formation of exercise habits [8, 11, 12]. However, there is substantial evidence that individuals differ in their affective responses to PA [8, 13]. Previous research revealed that different exercise intensities lead to different affective changes, which varies across individuals [14, 15]. Thus, further explanations are required in order to understand why some individuals engage in moderate-to-vigorous exercise despite the negative affective changes that might arise during PA.

One factor explaining variation in affective responses to different exercise intensities could be the role of emotion regulation processes [16,17,18]. Cognitive reappraisal (CR) is one of the most effective emotion regulation strategies [18] and refers to being able to change one’s cognitions about a situation to reduce the emotional impact of that situation [19]. CR strategies are beneficial for changing one’s appraisal and perspective of an emotion-eliciting situation before fully experiencing it [19, 20], and have been found to be positively linked to subjective well-being [21, 22]. Although research interest in the role of emotion regulation in PA behavior has increased in recent years, to date, research on the relationship between PA and emotion regulation remains relatively scarce [16, 20]. For example, reappraisal of the initial negative affect during moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) could be “It’s only for a few minutes and afterwards I will feel much better than before” or “The discomfort I feel actually shows that my muscles are getting stronger now”. CR is of particular interest because it is an adaptive emotion regulation strategy that can help transform affect during or after exercise into a positive (or less negative) affect [16, 23], which might support PA adherence.

The present study

The aim of the study was to examine the associations between CR and PA as well as the mediating role of AR (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that (1) CR is positively associated with PA behavior. Furthermore, we expected that (2) CR is positively associated with affective response to moderate as well as vigorous PA and (3) that affective response is positively correlated with PA behavior. Finally, it was expected that (4) affective response will act as a mediator between CR and PA.

Methods

Study design and procedure

A cross-sectional design with standardized self-report online questionnaires was employed (Unipark software; Tivian EFS Survey). After giving informed consent, participants filled in questions including socio-demographic information, PA behavior, affective response to PA, and the use of CR. Data collection ran between June and November 2022. Students received course credits in return for participation. To non-student participants no incentive was given.

Participants

Participants (N = 105) were recruited via flyers posted on the university website, an online recruitment platform (SONA system), and social media channels. After the exclusion of outliers (+/- 3 SD), and insufficient or missing data, the final sample consisted of N = 101 participants (73.3% were women; Mage = 25.91; SD = 6.95; range 18–58 years). 60 participants completed secondary education (56.5%), 41 university degree (39.6%), and 4 postgraduate degree (4.0%).

Measures

CR was assessed using the CR subscale of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire [24, German version by 25]. The subscale CR consists of 6 items (e.g. When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation) rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). An average score is calculated, where higher scores indicate greater frequency of using CR. The psychometric properties of the German version of the scale were acceptable; internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the questionnaire was reported as α = 0.74 [25].

Affective response (pleasure-displeasure continuum) to PA was measured using the one-item Feeling Scale [26, German version by 27]. After presenting the definition of moderate and vigorous PA, the participants were asked to rate their affect during moderate and vigorous PA separately, on a 11-point Likert scale ranging from − 5 (very bad) to + 5 (very good), with 0 indicating neutral affect. The convergent validity of the Feeling Scale German version ranges from r = .72 to 0.73 [27].

PA behavior as the dependent variable was measured using four items from the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form [28, German version by 29]. Participants were asked to indicate how many times and for how long (in minutes) on average per occasion they perform (1) moderate and (2) vigorous PA in a regular week. We calculated minutes per week spent with (1) moderate and (2) vigorous PA. A total weekly PA score (minutes/week) for MVPA was calculated by adding up the scores of moderate and vigorous PA. The questionnaire has acceptable measurement properties, with a good test-retest reliability of 0.80 and a fair to moderate criterion validity of rho = 0.30 [28].

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistical Software (SPSS) Version 27 [30]. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were computed. According to Cohen [31] effect sizes of correlations are considered to be small (r = .10), medium (r = .30), and large (r = .50). To test the mediation hypothesis, mediation analyses were conducted based on regression analyses and 10.000 bias corrected bootstraps using the PROCESS macro [32].

Results

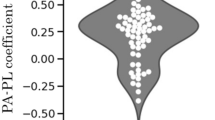

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the study variables are presented in Table 1. In line with hypotheses 1–3, CR was significantly and positively but weakly associated with moderate PA and vigorous PA, and moderately with total MVPA. Furthermore, significant positive correlations were observed between CR and affective response to moderate (moderate effect) and vigorous PA (small effect). Affective response to moderate PA was significantly correlated with moderate and MVPA (both small to moderate effects) but not with vigorous PA, while affective response to vigorous PA was associated with vigorous (small effect) and MVPA (moderate effect) but not with moderate PA.

Results of the mediation models

In order to test hypothesis 4, three mediation models were tested in which the dependent variables were moderate PA, vigorous PA, and MVPA respectively. The results of the mediation analysis for moderate PA revealed that CR was associated with affective response to moderate PA (b = 0.73; p < .001), and that affective response to moderate PA was associated with moderate PA (b = 17.10; p < .05). The indirect effect was significant (b = 12.47; SE = 6.33; 95% CI: 2.16, 26.96) whereas the direct effect, the relationship between CR and moderate PA was no longer significant (b = 13.82; p = .26).

With regard to vigorous PA, CR was significantly associated with affective response to vigorous PA (b = 0.57; p < .05), and affective response to vigorous PA with vigorous PA (b = 15.81; p < .01). The indirect effect was significant (b = 9.04; SE = 5.81; 95% CI: 0.30, 55.28). CR was also significantly associated with vigorous PA (direct effect; b = 28.00; p < .05) while controlling for affective response.

Thirdly, with MVPA as dependent variable and inserting the two mediators (AR to moderate as well as vigorous PA) in parallel to the model, the results showed that CR was significantly associated with affective response to moderate (b = 0.73; p < .001) as well as vigorous PA (b = 0.57; p < .05). CR was associated with MVPA (direct effect; b = 50.20; p < .01). AR to vigorous (b = 23.70; p < .01) PA was associated with MVPA but not moderate PA (b = -0.57; p = .96). Overall, the indirect effect of CR on MVPA through the affective response to vigorous PA was significant (b = 13.54; SE = 8.67; 95% CI: 0.61, 34.33), while the indirect effect for affective response to moderate PA was not (b = -0.41; SE = 8.79; 95% CI: -17.53, 17.58).

Discussion

The current study aimed to explore the role of CR and affective response to PA on PA behavior. Mainly, the correlational relationship among study variables were tested, and it was examined whether affective response mediates the relationship between CR and PA. Documented correlations were in the expected direction; CR was positively associated with affective response to both moderate and vigorous PA, affective response to moderate PA and to vigorous PA were positively correlated with the corresponding PA, and lastly CR was positively correlated with PA. Mediation analyses further revealed that affective response to moderate PA mediated the relationship between CR and moderate PA as affective response to vigorous PA mediated the relationship between CR and vigorous PA. Simply, CR predicted PA through affective response as expected. The more frequently CR was used, the more positive was the affective response to PA, and the more corresponding PA was engaged. These findings were in line with the current literature pointing that pleasantness of the affective response to PA is positively associated with PA [5,6,7,8]. Moreover, emotion regulation also plays an important role in regular PA. Changing the cognitive label that people ascribe to PA-related unpleasantness might help to reduce this unpleasantness, which might enhance the probability of repeating the behaviour. It could be argued that potentially there is a bidirectional relationship between emotion regulation and PA. With the use of CR, as the affective response becomes less negative, it contributes to PA engagement. Also, it has been supported that habitual exercise might enhance emotion regulation, specifically CR [16, 17] along with enhancing mood and cognition.

The results of the present study also showed that when the two mediators (affective response to moderate PA and vigorous PA) examined at once in their association with CR and MVPA, the indirect effect and thus mediation was significant for affective response to vigorous PA but not for moderate PA. In line with the earlier studies reporting that for intensity levels lower than vigorous PA produces improvements in positive affect [33], it can be argued that especially affective response to more intense PA, with the employment of CR strategies are more critical in the prediction of PA behavior. As higher intensity PA is typically associated with relatively less pleasant affective responses [15, 34], CR use could be mostly needed at higher intensity levels of PA. However, our results are at the same time in contrast to assumptions of the dual-mode theory of Ekkekakis [35] and empirical studies showing that cognitive reappraisal might become less effective as PA intensity approaches near-maximal efforts, as higher PA intensities (compared to lower intensities) are associated with lower neural activity in the prefrontal cortex, which is related to neural processes associated with cognitive reappraisal processes [36, 37].

Implications

The results of the study suggest that enhancing the positive affective response to PA using CR strategies might be a beneficial tool in order to increase adherence to PA especially, more intense forms of PA. Studies in other domains showed that with CR interventions, CR ability and the frequency of CR use can be increased [38, 39]. Hence, in the PA domain, CR interventions can be implemented in PA promotion programs, especially for those who are currently inactive. Future research should aim to test the effectiveness of CR interventions in PA domain.

Future longitudinal and experimental research examining moment-by-moment changes in participants’ affect before, during, and after PA and CR engagement is needed to explore and better document the relationship between PA and CR.

Limitations

We acknowledge several significant limitations in our study. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional design restricts our ability to establish causal relationships between CR, affective response, PA behavior. Secondly, the assessment method of study variables poses another limitation, considering self-report subjective ratings. Specifically, the measurement of affect based on typical experiences, rather than during or after bouts of moderate or vigorous PA, may introduce recall bias and limit the accuracy of our findings. Thirdly, conducting mediation analysis with a small sample of cross-sectional data and relying on retrospective self-reported variables pose additional challenges. Lastly, the highly educated and predominantly women sample of the study diminishes the generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

Despite limitations, the current study provided evidence in support of the prediction of PA behavior by CR through affective response. It is encouraged for future research to explore these relationships using longitudinal designs and objective measures of affect and physical activity.

Data availability

Data and materials will be shared upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CR:

-

Cognitive reappraisal

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- PA:

-

Physical activity

References

Meyer SM, Landry MJ, Gustat J, Lemon SC, Webster CA. Physical distancing ≠ physical inactivity. Translational Behav Med. 2021;11:941–4.

World Health Organization. Global status report on physical activity. 2022.

Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Polenakovic M, Bosevski M, Apostolopoulos V. Exercise and mental health. Maturita. 2017;106:48–56.

Wilson MG, Ellison GM, Cable NT. Basic science behind the cardiovascular benefits of exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(2):93–9.

Bok D, Rakovac M, Foster C. An examination and critique of subjective methods to determine exercise intensity: the talk test, feeling scale, and rating of perceived exertion. Sports Med. 2022;52(9):2085–109.

Ekkekakis P, Parfitt G, Petruzzello SJ. The pleasure and displeasure people feel when they exercise at different intensities: decennial update and progress towards a tripartite rationale for exercise intensity prescription. Sports Med. 201;41:641–71.

Ekkekakis P. People have feelings! Exercise psychology in paradigmatic transition. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;16:84–8.

Weyland S, Finne E, Krell-Roesch J, Jekauc D. (How) does affect influence the formation of habits in exercise? Front Psychol. 2020;11.

Edwards MK, Addoh O, Herod SM, Rhodes RE, Loprinzi PD. A conceptual neurocognitive affect-related model for the promotion of exercise among obese adults. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6:86–92.

Williams DM, Dunsiger S, Ciccolo JT, Lewis BA, Albrecht AE, Marcus BH. Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2008;9(3):231–45.

Schneider M, Dunn A, Cooper D. Affect, exercise, and physical activity among healthy adolescents. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31(6):706–23.

Woessner MN, Tacey A, Levinger-Limor A, Parker AG, Levinger P, Levinger I. The evolution of technology and physical inactivity: the good, the bad, and the way forward. Front Public Health. 2021;9:655491.

Ekkekakis P. Pleasure and displeasure from the body: perspectives from exercise. Cognition Emot. 2003;17(2):213–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302292.

Backhouse SH, Ekkekakis P, Biddle SJ, Foskett A, Williams C. Exercise makes people feel better but people are inactive: paradox or artifact? J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29(4):498–517.

Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, Petruzzello SJ. Some like it vigorous: measuring individual differences in the preference for and tolerance of exercise intensity. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2005;27(3):350–74.

Giles GE, Cantelon JA, Eddy MD, Brunyé TT, Urry HL, Mahoney CR, Kanarek RB. Habitual exercise is associated with cognitive control and cognitive reappraisal success. Exp Brain Res. 2017;235(12):3785–97.

Giles GE, Eddy MD, Brunyé TT, Urry HL, Graber HL, Barbour RL, Mahoney CR, Taylor HA, Kanarek RB. Endurance exercise enhances emotional valence and emotion regulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2018;12:398.

Wu J, Zhu L, Dong X, Sun Z, Cai K, Shi Y, Chen A. Relationship between physical activity and emotional regulation strategies in early adulthood: mediating effects of cortical thickness. Brain Sci. 2022;12(9):1210.

Gross JJ. (2013). Emotion regulation: taking stock and moving forward. Emotion. 2013; 13(3):359–365.

Berman CJ, O’Brien JD, Zenko Z, Ariely D. The limits of cognitive reappraisal: changing pain valence, but not persistence, during a resistance exercise task. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(19):3739.

McRae K, Jacobs SE, Ray RD, John OP, Gross JJ. Individual differences in reappraisal ability: links to reappraisal frequency, well-being, and cognitive control. J Res Pers. 2012;46(1):2–7.

Toh WX, Yang H. Common executive function predicts reappraisal ability but not frequency. J Exp Psychol. 2022;151(3):643–64.

Brand R, Kanning M. Sport tut gut?! Bewegung und Wohlbefinden. In Sport in Kultur und Gesellschaft [Sport is good for you?! Physical activity and well-being]. Springer Spektrum, Berlin, Heidelberg. 2021;379–391.

Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2003;85(2):348.

Abler B, Kessler HERQ. Emotion regulation questionnaire [Verfahrensdokumentation und Fragebogen]. Open Test Archive. Trier: ZPID; 2011. Leibniz-Institut für Psychologie (ZPID).

Hardy CJ, Rejeski WJ. Not what, but how one feels: the measurement of affect during exercise. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1989;11:304–17.

Maibach M, Niedermeier M, Sudeck G, Kopp M. Erfassung unmittelbarer affektiver Reaktionen auf körperliche Aktivität [Measuring affective responses to physical activity]. Z für Sportpsychologie. 2020.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, Pratt M, Ekelund U, Yngve A, Sallis JF, Oja P. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–95.

Wanner M, Probst-Hensch N, Kriemler S, Meier F, Autenrieth C, Martin BW. Validation of the long international physical activity questionnaire: influence of age and language region. Prev Med Rep. 2016;3:250–6.

IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge; 2013.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford; 2017.

Reed J, Ones DS. The effect of acute aerobic exercise on positive activated affect: a meta-analysis. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2006;7(5):477–514.

Ekkekakis P, Petruzzello SJ. Acute aerobic exercise and affect: current status, problems and prospects regarding dose-response. Sports Med. 1999;28:337–47.

Ekkekakis P. The dual-mode theory of affective responses to exercise in metatheoretical context: I. initial impetus, basic postulates, and philosophical framework. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;2(1):73–94.

Chang H, Kim K, Jung YJ, Kato M. Effects of acute high-intensity resistance exercise on cognitive function and oxygenation in prefrontal cortex. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2017;21(2):1.

Chang YK, Etnier JL. Exploring the dose-response relationship between resistance exercise intensity and cognitive function. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31(5):640–56.

Rodriguez LM, Dell JB, Lee KD, Onufrak J. Effects of a brief cognitive reappraisal intervention on reductions in alcohol consumption and related problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2019;33(7):637.

Rodriguez LM, Lee KD, Onufrak J, Dell JB, Quist M, Drake HP, Bryan J. Effects of a brief interpersonal conflict cognitive reappraisal intervention on improvements in access to emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms in college students. Psychol Health. 2020;35(10):1207–27.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dilara Jablinski for her help with data collection.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Medical School Hamburg provided open access funding.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CG contributed to the writing of the manuscript. IP contributed to study design, project management and supervision, data analysis, and drafting the paper. JS contributed to recruitment of participants, data collection, and drafting the paper. CG and IP carried out the revisions. All authors read, critically revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was formally approved by the ethics committee of the Medical School Hamburg and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent was received from all the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gürdere, C., Sorgenfrei, J. & Pfeffer, I. Cognitive reappraisal and affective response to physical activity: associations with physical activity behavior. BMC Res Notes 17, 185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06843-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-024-06843-3