Abstract

Objective

Researchers sought patient feedback on a proposed randomized controlled trial (RCT) in which gynecological cancer patients would modify their diets with intermittent fasting to gain insight into patients’ perspectives, receptivity, and potential obstacles. A convenience sample of 47 patients who met the inclusion criteria of the proposed RCT provided their feedback on the feasibility and protocols of the RCT using a multi-method approach consisting of focus groups (n = 8 patients) and surveys (n = 36 patients).

Results

Patients were generally receptive to the concept of intermittent fasting, and many expressed an interest in attempting it themselves. Patients agreed that the study design was feasible in terms of study assessments, clinic visits, and biospecimen collection. Feedback on what could facilitate adherence included convenient appointment scheduling times and the availability of the research team to answer questions. Regarding recruitment, patients offered suggestions for study advertisements, with the majority concurring that a medical professional approaching them would increase their likelihood of participation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the research community undergoes a “revolutionary” paradigm shift from viewing patients as “subjects” to “experts,” new projects can involve patients in the research lifecycle, from study design to data translation [1,2,3]. Patients are responsible for many developments of interest, such as identifying research priorities [3], and hel** recruit and retain participants [4,5,6]. Patients benefit via new access to scientific information, a place to process their experiences, and a sense of purpose from making a difference [7].

The present study leverages lived experiences of current and former gynecologic cancer patients to understand the feasibility and compliance concerns of a proposed randomized control trial (RCT), Intermittent Fasting to Restrict Cancer (iFIRE-C), in which gynecological cancer patients in remission or undergoing chemotherapy/radiation treatment will be randomly assigned to eat regularly (control group) or perform intermittent fasting (IF).

Methods

Strategy

A mixed-methods strategy involving focus groups (FGs) and a brief online survey was employed to gain patient perspectives. The Institutional Review Board of Henry Ford Health (HFH) granted ethical approval (#15521-31) for this study.

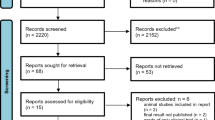

Recruitment of participants

The sample pool consisted of HFH patients 18 years of age or older who currently have or previously had gynecologic cancer such as cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar. Potential participants were ascertained using a convenience sample of patients from HFH’s electronic medical records system, and a targeted email list of gynecological oncology patients at HFH’s Cancer Center. Nonprobability purposeful snowball sampling [8] was also used by HFH’s Patient Engaged Research Center [9] to identify potential participants. Potential participants received recruitment assets via email. Interested and eligible participants received a digital consent form via REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) [2, 10]. Prior to the FG, consented participants were emailed iFIRE-C’s purpose, duration, procedures, and the “Fasting & Food Log.”

To collect additional perspectives, the Patient Engaged Research Center staff emailed prospective patients, excluding those who had already participated in FGs, to complete a brief online survey.

Data generation

Focus groups

Virtual FGs were conducted via Webex (Cisco Systems, Inc., San Jose, CA); consent was reconfirmed. FGs were facilitated by Patient Engaged Research Center staff trained in qualitative research methodologies. A four-section moderator guide [11] was utilized. In section one, the facilitator and patients introduced themselves. The second section described the goal of gaining the patient perspective on iFIRE-C. Section three contained key questions regarding dieting experiences, opinions on IF, the study title and design, and recruitment. In the fourth section, the facilitator summarized the discussion and asked patients for further clarifications or outstanding questions. Patients were compensated for their time.

Survey

Similar queries as in the FGs were posed in a 24-question survey developed by investigators for this study specifically, including a mix of open- and closed-ended questions about recruitment methods, communication preferences, and intervention feasibility for iFIRE-C (Supplementary file).

Data analysis

Focus groups

The FG transcripts were analyzed using deductive coding, with initial codes developed based on aspects of iFIRE-C and the moderator guide’s main questions, resulting in 6 topic areas (Table 1). This deductive analysis conceptualized patients’ perspectives across the FGs regarding the feasibility of the proposed study components, within the context of their lived cancer experiences.

Survey

The survey data was analyzed using SPSS Statistics (Version 26; IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics were generated for all closed-ended questions, and open-ended questions were summarized qualitatively.

Results

Focus Groups

After 5 weeks of advertising, 20 individuals responded, but not all signed a consent form. Eventually, 8 individuals participated across 3 FGs between June 20, 2022 and July 6, 2022. FG size ranged from 1 to 4 and lasted between 20 and 50 min. Results are presented by topic area below.

Patients’ past experiences with dieting

Patients had attempted WeightWatchers (WW International, New York, NY) (n = 4), IF (n = 3), and ketogenic diet (n = 1), with varying degrees of success. One individual who practices IF has been successfully maintaining it for the past 2–3 years, whereas the individual who tried a ketogenic diet could not sustain the restrictions.

Patients’ understanding and attitude toward IF

Most patients knew about IF and knew someone who had tried it. Regarding their perspectives on IF as cancer patients, 2 patients mentioned asking their respective doctors about IF recently, and while both were told that more scientific evidence is required, one patient stated, “I would do it in a heartbeat if I knew it would be helpful either for survival statistics or feeling better.” Other positive emotions centered around weight management and long-term health.

Some patients explained that receiving chemotherapy would be a barrier. Concerns included needing to take advantage of opportunities to keep food down and losing too much weight, and facilitators included the sometimes irregular “schedule” of life during treatment.

One response addressed the “information overload” experienced by cancer patients, illustrated by the quote, “As a cancer patient, you have so much getting thrown at you…so many treatment options and doctor’s appointments and other worries, work and family and things like that. I don’t know if someone presented me with an intermittent fasting diet, like, why would you want to put me on a diet? I’m going through cancer. It would have to be explained in such a way to show me the benefits of how is this helpful to me as someone who is going through cancer treatment.”

When asked how long patients might be able to fast, most responses ranged between 8 and 12 h. The primary concern about adherence was social relationships: eating with loved ones at home and outside. Holidays and vacations were of special concern (n = 3 mentions).

Thoughts on the proposed RCT title (iFIRE-C)

Participants liked the study moniker, iFIRE-C, calling it “catchy” (n = 5) and “easy to understand,” and agreed they would not alter it. One person stated that the title evokes action, and “doing something positive.” Another person said they were a bit “hung up on” the word restrict, wondering if it referred to restricting active cancer or cancer in remission.

Thoughts on iFIRE-C design and assessments: The patients reviewed relevant documents prior to the FGs and provided input on aspects of iFIRE-C’s RCT design. Their perspectives are outlined in Table 2.

Thoughts on the iFIRE-C supports

Here, patients focused on engagement with study team members, nutrition support, and compensation. Patients indicated that supports required to remain engaged in the study may differ by person. Calls, emails, and text messages were mentioned as methods to check in, and patients considered it important to use a tailored approach based on individual preference. Additionally, patients agreed that having study support available to address patient questions would be advantageous.

The moderator inquired if nutrition support from a registered dietician would encourage study compliance. Patients liked the concept, with one patient expanding that the “general population doesn’t know the best foods, the healthiest ones that keep you full longer, or foods to eat at certain times of the day.“

Feedback on iFIRE-C’s gratuity of $50 per 45–60-minute visit/sample collection included references to currently high gas prices and the necessity to travel to study appointments. A patient explained that while this amount would not motivate an uninterested person, cancer patients and survivors would be motivated by the possibility of improving their own condition or the condition of future patients.

Patient suggestions foriFIRE-Crecruitment and advertisement: Patients concurred that they would be most likely to participate if approached by a medical professional. Patient recruitment ideas included having someone present at a cancer support group and contacting people/leaving them with a callback number.

The patients also provided feedback on the drafted study flyer. They suggested flyers should include a catchy tagline requesting assistance and improve aesthetics by minimizing text. Patients believed that highlighting the benefits of participation and providing straightforward communication regarding time commitment would be relevant additions. They supported the use of both electronic and paper flyers.

Survey

All 36 respondents were female, and the majority identified as white race. They were primarily not Hispanic or Latino, and the majority (n = 28) were 45 years of age or older.

Patients reported being most receptive to emails (n = 16), texts (n = 12), or in-person interventions (n = 13), and less receptive to telephone calls and social media approaches. The in-person approach by a medical professional would increase their likelihood of enrolling (n = 26).

Concerning communication with the study team, patients favored email (n = 15), and many were willing to receiving weekly (n = 9) or bi-monthly (n = 16) communications.

To determine the feasibility of iFIRE-C, present eating habits were assessed. Most patients endorsed eating 2–3 times (n = 21) or 4–5 times (n = 12) per day. There were mixed responses regarding nausea during chemotherapy (14 had nausea; 13 said they did not, and 9 did not respond). A total of 15 patients responded to a free-text query about the side effects of chemotherapy on their appetite. The responses centered on alterations in taste (food tastes “like metal”), a lack of appetite, and nausea. Regarding fasting, 23 patients had previous personal experience with fasting, and 25 indicated that their work/lifestyle would not interfere with their ability to adhere to a fasting regimen. Many patients (n = 19) agreed that they would be more likely to adhere to a fasting diet if they were permitted to consume water, coffee, or herbal tea (sans sugar/artificial sweeteners) during their fasting period. Finally, when asked if they would be interested in participating in a study doing IF for 12 h or more/day over a span of 12 + weeks, 16 patients indicated they would be interested.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility of iFIRE-C, with the goal of incorporating patient feedback. Key patient perspectives were gathered in a multi-pronged approach, which included virtual FGs and an online survey. Overall, our analyses show that the patients were receptive to the concept of IF if it would help the disease outcome.

A recent review notes that various short-term RCTs have shown that fasting may impact cancer risk factors, but long-term trials have not shown significant improvements, and further research is required [12]. Thus, given the paucity of research on IF in cancer prevention, and the importance of including patient perspective in RCT design, iFIRE-C seeks to fill a critical gap in cancer clinical trial research.

Cancer is associated with emotional distress [13,14,15], which may be caused by fear of recurrence, lifestyle changes, and familial and financial concern. Patients had reported their primary concerns peaked at 6 months after the cancer diagnosis and centered on their illness, treatment, and the potential outcomes of their illness [14]. In the present study, it was evident that patients, at various stages of post-diagnosis and treatment, remained concerned about cancer prevention in the future, not only for themselves, but also for others with cancer, highlighting the altruistic attitudes of the participants.

This study revealed that patients had tried diet modifications in the past, and all had some knowledge about IF and would be willing to try it. They perceived a clinical trial in that area as feasible and appeared interested in fasting for weight management. Patients deemed the proposed study design to be feasible as well. Notably, the gradual increase of the fasting window and the availability of support were viewed as especially positive. Feedback regarding the study assessments centered on the convenience of all aspects of clinic visits and sample collections. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that patient convenience can support intervention adherence [16,17,18].

Regarding recruitment, both FG participants and survey respondents appreciated being approached by a medical professional. Previous research has emphasized the importance of the patient-provider relationship in recruitment [19], and communication between patient and provider increases adherence to study protocols [18].

Conclusions

Our study identified key themes pertinent to the design of cancer RCTs. Utilizing patient voices during the study design phase improves feasibility and provides opportunities for patient centered RCTs.

Limitations

-

One FG had only 1 patient, which did not allow for any patient-to-patient interaction and hampered the patient’s ability to construct social context for the discussion.

-

We did not distinguish between the types of gynecologic cancer, which limit the applicability of the feasibility analysis to each category of gynecologic cancer.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FG:

-

Focus groups

- HFH:

-

Henry Ford Health

- IF:

-

Intermittent fasting

- iFIRE-C:

-

Intermittent Fasting to Restrict Cancer

- RCT:

-

Randomized control trial

References

Johansson V. From subjects to experts–on the current transition of patient participation in research. Am J Bioeth. 2014;14:29–31.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208.

Rouleau G, Bélisle-Pipon J-C, Birko S, Karazivan P, Fernandez N, Bilodeau K, et al. Early career researchers’ perspectives and roles in patient-oriented research. Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4:35.

Chhatre S, Jefferson A, Cook R, Meeker CR, Kim JH, Hartz KM, et al. Patient-centered recruitment and retention for a randomized controlled study. Trials. 2018;19:205.

Edwards V, Wyatt K, Logan S, Britten N. Consulting parents about the design of a randomized controlled trial of osteopathy for children with cerebral palsy. Health Expect. 2011;14:429–38.

Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T, Wang Z, Nabhan M, Shippee N, et al. Patient engagement in research: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89.

Thompson J, Bissell P, Cooper CL, Armitage CJ, Barber R. Exploring the impact of patient and public involvement in a cancer research setting. Qual Health Res. 2014;24:46–54.

Parker C, Scott S, Geddes A. Snowball sampling. In: Atkinson P, Delamont S, Cernat A, Sakshaug JW, Williams RA, editors. SAGE research methods foundations. SAGE Publishing; 2019. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526421036831710.

Olden HA, Santarossa S, Murphy D, Johnson CC, Kippen KE. Bridging the patient engagement gap in research and quality improvement utilizing the Henry Ford Flexible Engagement Model. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2022;9:35–45.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–81.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1990.

Clifton KK, Ma CX, Fontana L, Peterson LL. Intermittent fasting in the prevention and treatment of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:527–46.

Fallowfield L, Ratcliffe D, Jenkins V, Saul J. Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1011–5.

Booth K, Beaver K, Kitchener H, O’Neill J, Farrell C. Women’s experiences of information, psychological distress and worry after treatment for gynaecological cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:225–32.

Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Rush R, Cargill A, Storey D, et al. Emotional distress in cancer patients: the Edinburgh Cancer Centre symptom study. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:868–74.

Zheng W, Chang B, Chen J. Improving participant adherence in clinical research of traditional chinese medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:376058.

King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL, Debusk RF. Strategies for increasing early adherence to and long-term maintenance of home-based exercise training in healthy middle-aged men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1988;61:628–32.

Cao HJ, Li X, Li XL, Ward L, **e ZG, Hu H, et al. Factors influencing participant compliance in acupuncture trials: an in-depth interview study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0231780.

Howerton MW, Gibbons MC, Baffi CR, Gary TL, Lai GY, Bolen S, et al. Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109:465–76.

Acknowledgements

We thank Janine Hussein for moderating the focus groups.

Funding

This study was supported by Henry Ford Cancer Team Science Award to RR, Ruth McVay Philanthropic Funds. RR is also supported by NIH/NCI R01CA249188. The funding body had no role in the design of the study or collection or analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR cleaned the focus group data, created the analysis plan, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. SS contributed to study design, interpreted the data, and substantively revised the manuscript. DM contributed to study design and created and distributed the survey. MPU was involved in initial discussions of the study and edited the manuscript. AM was involved in initial discussions of the study and edited the manuscript. MH was involved in initial discussions of the study and edited the manuscript. RR designed the study, interpreted the data, and substantively revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Board of Henry Ford Health granted ethical approval (#15521-31) for this study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Participants provided signed informed consent prior to participation, using an e-consent form.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Redding, A., Santarossa, S., Murphy, D. et al. A patient perspective on applying intermittent fasting in gynecologic cancer. BMC Res Notes 16, 190 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06453-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06453-5