Abstract

Background

Tick-borne rickettsioses are considered important emerging zoonoses worldwide, but their etiological agents, rickettsiae, remain poorly characterized in northeastern China, where many human cases have been reported during the past several years. Here, we determined the characteristics of Rickettsia spp. infections in ticks in this area.

Methods

Ticks were collected by flagging vegetation from Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces of northeastern China followed by morphological identification. The presence of Rickettsia spp. in ticks was detected by PCR targeting the 23S-5S ribosomal RNA intergenic spacer, citrate synthase (gltA) gene, and 190-kDa outer membrane protein gene (ompA). The newly-generated sequences were subjected to phylogenetic analysis using the software MEGA 6.0.

Results

The overall infection rate of Rickettsia spp. was 6.12 %. Phylogenetic analyses based on the partial gltA and ompA genes demonstrated that rickettsiae detected in the ticks belong to four species, including “Candidatus Rickettsia tarasevichiae”, Rickettsia heilongjiangensis, Rickettsia raoultii, and a potential new species isolate. The associated tick species were also identified, i.e. Dermacentor nuttalli and Dermacentor silvarum for R. raoultii, Haemaphysalis concinna and Haemaphysalis longicornis for R. heilongjiangensis, and Ixodes persulcatus for “Ca. R. tarasevichiae”. All Rickettsia spp. showed significantly high infection rates in ticks from Heilongjiang when compared to Jilin Province.

Conclusion

Rickettsia heilongjiangensis, R. raoultii and “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” are widely present in the associated ticks in northeastern China, but more prevalent in Heilongjiang Province. The data of this study increase the information on the distribution of Rickettsia spp. in northeastern China, which have important public health implications in consideration of their recent association with human diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tick-transmitted diseases have become an increasing public health problem [1–3]. Tick-borne rickettsioses are considered important emerging zoonoses worldwide, due to tick distribution alterations, shifting climates, and accelerating urbanization [4, 5]. These diseases share characteristic clinical features, including fever, asthenia, anorexia, nausea, headache, rash and occasional eschar formation at the site of the tick bite.

At least nine species or subspecies of tick-borne rickettsiae have been identified during the past 30 years in China, including Rickettsia heilongjiangensis, Rickettsia sibirica sp BJ-90, Rickettsia raoultii and “Candidatus Rickettsia tarasevichiae” [6–9]. Rickettsia heilongjiangensis was primarily identified in Suifenhe and Luobei of Heilongjiang Province in 1984, and isolated from the blood of a tick-bitten patient in the same place ten years later [10–12]. Since then, this organism has been detected or isolated in other countries, including Russia, Japan and Thailand [13–15]. Rickettsia heilongjangensis was first proven responsible for human disease in 1996, and 34 human cases have been reported [3]. Rickettsia sibirica strain BJ-90 was primarily detected in Dermacentor sinicus ticks from Bei**g, and had not been considered as a pathogenic agent for humans until 2012 when an old farmer from Mudanjiang of Heilongjiang Province was diagnosed with infection of this organism [7]. Rickettsia raoultii, initially detected in Russia in 1999 and considered a novel species in 2008, is prevalent in various regions of Asia and Europe [16–19]. In 2009, R. raoultii was determined as a human pathogen in France [20]. In China, DNA of this bacterium was first detected in Jilin Province in 2008 [21]. Recently, R. raoultii has been found prevalent in Heilongjiang, **njiang and Tibet provinces [22–25]. However, the first human case of R. raoultii infection in China was reported in the northeast in 2014 [9]. “Ca R. tarasevichiae”, belonging to the so-called ancestral group that was traditionally considered nonpathogenic, was first detected in Ixodes persulcatus ticks collected from various regions of Russia, and subsequently recorded in a wide territory from Estonia to Japan [26–28]. In 2013, specific DNA of “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” was detected in blood samples of five misdiagnosed patients in northeastern China [8].

More than 500 human cases have been reported in China in the past 13 years, mostly in the northeastern region of the country, suggesting an increasing risk of Rickettsia infection. We therefore conducted this study to detect and characterize the rickettsiae in ticks collected in northeastern China.

Methods

Collection of ticks

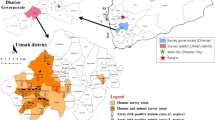

During April and May 2015, ticks were collected by flagging vegetation in nine regions of northeastern China, including Jilin (42°39′–43°20′N, 126°12′–127°23′E), Dunhua (42°27′–43°2′N, 129°50′–130°44′E) and Hunchun (42°47′–43°6′N, 130°6′–130°12′E) located in Jilin Province, and Yichun (47°24′–48°3′N, 128°23′–129°37′E), Jiamusi (46°43′–47°11′N, 133°12′–133°56′E), Shuangyashan (46°27′–46°58′N, 131°12′–131°23′E), Tongjiang (47°43′–48°3′N, 133°29′–133°44′E), Hulin (45°33′–45°54′N, 132°49′–133°23′E) and Suifenhe (44°23′N, 131°9′E) situated in Heilongjiang Province (Fig. 1). The tick species were identified following morphological criteria as described previously or using molecular biology tools after PCR targeting the 16S ribosomal RNA gene with the forward primer TickHF (5′-GGT ATT TTG ACT ATA CAA AGG TAT TG-3′) and the reverse primer TickHR (5′-TTA TTA CGC TGT TAT CCC TAG AGT ATT-3′) [29].

Detection of rickettsiae

The sampled ticks were pooled, approximately 15 ticks per pool, based on the tick species and sampling sites. After washing with 70 % ethanol and double distilled water, the pooled ticks were homogenized in 1 ml sterile PBS. DNA was extracted from 200 μl tick homogenates using TIANamp Genomic DNA Purification System (TIANGEN, Bei**g, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The tick pools were initially screened for the presence of Rickettsia spp. by amplifying the 23S-5S rRNA intergenic spacer by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers RCK/23-5-F and RCK/23-5-R as described previously [30]. Double-distilled water and a previously determined positive sample were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

The positive pools were subsequently analyzed by amplifying the partial citrate synthase (gltA) gene and outer membrane protein A (ompA) gene of Rickettsia spp. by PCR with the primers CS2d and CSEndr for gltA targeting a 1289 bp fragment, and Rr190.70p and Rr190.602n for ompA targeting a 533 bp fragment [8, 31]. The PCR products were cloned into pMD18-T vector (Takara, Dalian, China) and sequenced.

Phylogenetic analysis

The newly-generated sequences were aligned exclusively, or together with those retrieved from the GenBank database using the software ClustalW 2.0. Phylogenetic trees were generated in a Maximum Likelihood analysis using the software Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) version 6.0 [11].

Statistical analysis

The infection rates of Rickettsia spp. in ticks were calculated using the software PooledInfRate version 4.0 (By Biggerstaff, Brad J., a Microsoft® Office Excel© Add-In to compute prevalence estimates from pooled samples. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2009). The software provides three computing methods for infection rate estimation, including bias-corrected maximum likelihood estimation (Bias-corrected MLE) and minimal infection rate (MIR). The former exhibits better accuracy than the latter, but requires that not all the pools are positive. Statistical significance was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test and Chi-square test; P < 0.05 is considered significant.

Results

A total of 2928 ticks, including 2813 adults and 115 nymphs, were collected from Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces of northeastern China (Fig. 1). In particular, the nymphs were exclusively collected from **gxin town (42°30′N, 130°38′E) in Jilin Province. The species of ticks were morphologically determined as Dermacentor nuttalli (n = 253), Dermacentor silvarum (n = 204), Haemaphysalis concinna (n = 412), Haemaphysalis longicornis (n = 390, 275 adults and 115 nymphs) and Ixodes persulcatus (n = 1669). Based on species and sampling site, the identified ticks were subsequently assigned into 204 pools, of which 201 were adults and three were nymphs (detailed in Additional file 1: Table S1). In order to ensure the accuracy of identification of tick species, we also analyzed the partial sequence of 16S ribosomal RNA gene of a portion of ticks using BLAST. The sequences (354 nt, GenBank accession no. KX305956) derived from five tick pools which were morphologically determined as I. persulcatus were genetically identical to one another and presented 100 % similarity to that of I. persulcatus isolate Irk5m (accession no. JF934741.1). The partial 16S rRNA gene sequences (252 nt, accession no. KX305957) obtained from D. nuttalli pools were also identical to each other but differed at two nucleotide positions from that of the nearest tick species (D. nuttalli isolate XJ088, accession no. JX051114.1). The three pools of nymphs and the adult H. longicormis ticks shared the same partial nucleotide sequence (127 nt, accession no. KX305958) of the 16S rRNA gene that was most related (99 % similarity) to the sequence of H. longicormis isolate YN07 (accession no. JX051064.1). With the exception of H. concinna absent in samples from Jilin, all these tick species were found in both provinces. Dermacentor species were more prevalent (Pearson Chi-square test; χ 2 = 564.0, df = 1, P < 0.0001) in Jilin (37.4 %) in comparison with Heilongjiang (4.0 %), where I. persulcatus was the predominant tick species (Table 1).

To investigate the presence of Rickettsia spp. in tick samples, molecular screening was first performed using the universal primer set. In total, 122 tick pools out of 2928 (6.12 %) ticks were found positive for Rickettsia spp. To identify the Rickettsia spp. in these positive samples, partial gltA (1289 bp) and ompA (533 bp) gene sequences were further obtained and sequenced. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that these sequences could be clustered into four clades (Additional file 2: Figure S1). After BLAST on the NCBI website, sequences in the GenBank database most similar to the query sequences were retrieved and used for phylogenetic analysis, revealing that clades 1, 2 and 4 were corresponding to “Ca. R. tarasevichiae”, R. heilongjiangensis and R. raoultii, respectively (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). Two identical sequences obtained from H. longicornis collected in **gxin town of Hunchun city constituted the clade 3. The affirmatory species of Rickettsia most-related to clade 3 was “Candidatus Rickettsia vini” which shared 96.6 % nucleotide similarity of ompA sequence and 99.7 % of gltA sequence. Current criteria for sequence-based classification of a Rickettsia species as a new “Candidatus Rickettsia” species requires the sequence similarity of the newly identified species with the established Rickettsia spp. should be: < 99.9 % for gltA and < 98.8 % for ompA [11]. Phylogenetic analyses based on gltA and ompA sequence showed the clade 3 as an independent clade (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). These results suggest that species in the clade 3 could be a potential new Rickettsia species. We propose to provisionally designate it as “Candidatus Rickettsia **gxinensis”.

Phylogenetic trees based on partial sequences of gltA (1289 bp) gene. Sequences of the Rickettsia species detected in the present study were aligned with those retrieved from the GenBank database. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Maximum Likelihood method and trees were tested by bootstrap** (1000 pseudoreplicates). Rickettsia bellii was used as the outgroup. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions (Kimura 2-parameter model) per site. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions (Kimura 2-parameter model) per site. Sequences for species detected in the present study are indicated by geometric shapes and colours

Phylogenetic tree based on partial sequences of ompA (533 bp) gene. Sequences of the Rickettsia species detected in the present study were aligned with those retrieved from the GenBank database. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Maximum Likelihood method and trees were tested by bootstrap** (1000 pseudoreplicates); Rickettsia felis was used as the outgroup. The scale-bar indicates the number of substitutions (Kimura 2-parameter model) per site. Sequences for species detected in the present study are indicated by geometric shapes and colours

The overall infection rate of rickattsiae in Dermacentor ticks in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces (4.42–5.16 % and 10.30–10.64 %, respectively) were higher than those of the other tick species (0–3.12 % and 5.42–7.95 %, respectively). The infection rate of rickettsiae in ticks from Heilongjiang were significantly higher than that of Jilin (Pearson Chi-square test; χ 2 = 5.355, df = 1, P = 0.0207) (Table 1).

Rickettsia raoultii was detected with comparable infection rate in both D. nuttalli and D. silvarum with infection rate strikingly higher in Heilongjiang (10.30–10.64 %) as compared to Jilin (4.42–5.16 %) (Fisher’s exact test; χ 2 = 6.595, df = 1, P = 0.017). Haemaphysalis longicormis from Jilin Province was also detected positive (1.58 %) for R. raoultii (Table 1). The potential new Rickettsia species “Ca. R. **gxinensis” was merely found in two tick pools of nymphs of H. longicormis from **gxin in Jilin Province with an infection rate of 0.92 %. DNA of R. heilongjiangensis was exclusively detected in Haemaphysalis ticks from Heilongjiang Province with infection rate of 4.96 % in H. concinna and 5.42 % in H. longicormis. “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” DNA was only present in I. persulcatus with one exception in H. longicormis collected from Shuangyashan of Heilongjiang Province (Fig. 1).

The representative partial sequences of gltA and ompA gene in the present study have been deposited to Genbank (see accession numbers in Table 2).

Discussion

To date, twenty-one tick species of seven genera have been reported in northeastern China [32]. In the present study, we only collected five tick species, including D. nuttalli, D. silvarum, H. concinna, H. longicornis and I. persulcatus. We also demonstrated that the tick population in Jilin Province is different from that of Heilongjiang Province. For example, Dermacentor species are predominant in Jilin, compared with Heilongjiang Province. Haemaphysalis concinna had been reported in Hunchun and Dunhua (Jilin Province) [32], but it was not found in this study. The possible reasons may come from the limitation of sampling period and regions, and altered tick population induced by the interruption of nature balance [33].

All of the tick species identified in our study can function as vectors that could transmit various pathogens to humans and animals. For instance, H. longicornis is a vector for R. heilongjiangensis, “Candidatus Rickettsia hebeiii”, Ehrilchia chaffeensis, Borrelia garinii and Babesia mircroti [3]. In northeastern China, Rickettsia spp. spread by human-bitten ticks could be a serious public health problem, and several Rickettsia spp. have been identified or isolated from ticks or patients, including R. heilongjiangensis, Rickettsia sibrica, Rickettsia japonica, R. raoultii and “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” during the past 30 years [3]. In the current study, three Rickettsia spp., including R. heilongjiangensis, R. raoultii, “Ca. R. tarasevichiae”, and a potential new species “Ca. R. **gxinensis”, were detected in ticks, with an overall infection rate of 6.12 %. Previous reports showed that Rickettsia infection rates ranged from 1.53 to 32.25 % in a certain species, or a certain vector, or a certain origin of northeastern China [21, 34]. Intriguingly, the infection rates of rickettsiae in Heilongjiang Province were found to be strikingly higher than those of Jilin Province in the present study. The geography-based dissimilarity of Rickettsia presence provides new insight for the prevention and control of tick-borne rickettsioses. In northeastern China, R. heilongjiangensis was detected in three counties of Heilongjiang with an infection rate of 4.7 % [15]. Rickettsia heilongjiangensis was initially detected in D. silvarum and Haemaphysalis ticks [12], but only found in the latter in this study, which confirmed the previous finding that Haemaphysalis ticks were the major vector of R. heilongjiangensis [35]. Despite the presence of R. heilongjiangensis in Jilin Province was proven in rodent animals and humans [15], we only detected it in ticks from Heilongjiang Province in the current study. This result suggests R. heilongjiangensis could be more prevalent in Heilongjiang Province. At the China-Russia border, R. raoultii was considered to be the predominant Rickettsia in D. silvarum; this was confirmed in the present study [22]. Furthermore, we also demonstrated that in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces, R. raoultii appeared to be predominant in D. nuttalli, as already shown in a study in Mongolia [36]. Although R. raoultii was detected in other tick species, such as Haemaphysalis erinacei and I. persulcatus, we did not amplify DNAs of this Rickettsia species from ticks except for Dermacentor species, suggesting that Dermacentor species may be the major vector for R. raoultii, as stated in the previous studies [22, 23]. “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” was recently found in patients and I. persulcatus in Heilongjiang Province in China, renewing the old concept that members of the ancestral group of Rickettsia were nonpathogenic [8, 34]. In this study, the presence of “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” was extended from Heilongjiang to Jilin Province. For the first time, we detected “Ca. R. tarasevichiae” in H. longicornis in China, which confirmed the presence of this organism in tick species besides I. persulcatus, as reported in Russia [37].

In addition, we also detected a new variant “Ca. R. **gxinensis”. Phylogenetic analyses based on both ompA and gltA gene sequences indicated this may be a new species. However, additional studies are required to verify this possibility. “Ca. R. **gxinensis” is closely related to “Ca. Rickettsia vini” and “Ca. Rickettsia davousti”. Although the Candidatus species have not been identified as human or animal pathogens despite a wide geographic distribution, we could not exclude the potential threat for humans and animals [38, 39].

Our study had some limitations. First, our investigation was subjected to bias because the infection rates were calculated in pooled samples, and we could not exclude the possibility of various strains in each pool. Therefore, the actual infection rates might be higher than stated above. Second, since our interests mainly focused on the infection rates in different areas and tick species in northeastern China, we did not identify the sex of the ticks. Thus, it is impossible to ascertain the precise infection rate of Rickettsia spp. based on the vector gender in this study.

Conclusion

We determined that D. nuttalli, D. silvarum, H. concinna, H. longicornis and especially I. persulcatus were the major tick species, and acting mainly as vectors for R. raoultii, R. heilongjiangensis and “Ca. R. tarasevichiae”, respectively, in northeastern China. These rickettsiae were more prevalent in Heilongjiang as compared to Jilin Province. These data increase the information on the distribution of rickettsiae in northeastern China, which have important public health implications in consideration of their recent association with human diseases.

Abbreviations

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal RNA

- gltA :

-

Citrate synthase gene

- ompA :

-

190-kDa outer membrane protein gene

References

Liu Q, He B, Huang SY, Wei F, Zhu XQ. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, an emerging tick-borne zoonosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):763–72.

Gong SS, He B, Wang ZD, Shang LM, Wei F, Liu Q, et al. Nairobi sheep disease virus RNA in ixodid ticks, China, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(4):718–20.

Fang LQ, Liu K, Li XL, Liang S, Yang Y, Yao HW, et al. Emerging tick-borne infections in mainland China: an increasing public health threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(12):1467–79.

Dantas-Torres F, Chomel BB, Otranto D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a One Health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28(10):437–46.

Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):719–56.

Wu XB, Na RH, Wei SS, Zhu JS, Peng HJ. Distribution of tick-borne diseases in China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:119.

Jia N, Jiang JF, Huo QB, Jiang BG, Cao WC. Rickettsia sibirica subspecies sibirica BJ-90 as a cause of human disease. New Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1176–78.

Jia N, Zheng YC, Jiang JF, Ma L, Cao WC. Human infection with Candidatus Rickettsia tarasevichiae. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(12):1178–80.

Jia N, Zheng YC, Ma L, Huo QB, Ni XB, Jiang BG, et al. Human Infections with Rickettsia raoultii, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(5):866–68.

Wu YM, Zhang ZQ, Feng L. Rickettsia heilongjiangii and Heilongjiangii tick-borne spotted fever. J Microbiol. 2005;6(25):95–97 (in Chinese).

Fournier PE, Dumler JS, Greub G, Zhang J, Wu Y, Raoult D. Gene sequence-based criteria for identification of new Rickettsia isolates and description of Rickettsia heilongjiangensis sp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(12):5456–65.

Luo D, Wu YM, Wang B, Liu GD, Li JZ. A new member of the spotted fever group of rickettsiae – Rickettsia heilongjiangii. Chin J Microbiol Immunol. 1985;7(5):250–53 (in Chinese).

Ando S, Kurosawa M, Sakata A, Fujita H, Sakai K, Sekine M, et al. Human Rickettsia heilongjiangensis infection, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(8):1306–08.

Shpynov SN, Fournier PE, Rudakov NV, Samoilenko IE, Reshetnikova TA, Yastrebov VK, et al. Molecular identification of a collection of spotted fever group rickettsiae obtained from patients and ticks from Russia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74(3):440–43.

Wu YM, Zhang ZQ, Wang HJ, Yang Q, Feng L, Wang JW. Investigation on the epidemiology of Far-East tick-borne spotted fever in the Northeastern area of China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2008;29(12):1173–75 (in Chinese).

Rydkina E, Roux V, Fetisova N, Rudakov N, Gafarova M, Tarasevich I, et al. New rickettsiae in ticks collected in territories of the former Soviet Union. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5(6):811–14.

Mediannikov O, Matsumoto K, Samoylenko I, Drancourt M, Roux V, Rydkina E, et al. Rickettsia raoultii sp. nov., a spotted fever group rickettsia associated with Dermacentor ticks in Europe and Russia. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008;58(Pt 7):1635–39.

Portillo A, Santibanez S, Garcia-Alvarez L, Palomar AM, Oteo JA. Rickettsioses in Europe. Microbes Infect. 2015;17(11–12):834–38.

Orkun O, Karaer Z, Cakmak A, Nalbantoglu S. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks in Turkey. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5(2):213–18.

Parola P, Rovery C, Rolain JM, Brouqui P, Davoust B, Raoult D. Rickettsia slovaca and R. raoultii in tick-borne rickettsioses. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(7):1105–08.

Cao WC, Zhan L, De Vlas SJ, Wen BH, Yang H, Richardus JH, et al. Molecular detection of spotted fever group Rickettsia in Dermacentor silvarum from a forest area of northeastern China. J Med Entomol. 2008;45(4):741–44.

Wen J, Jiao D, Wang JH, Yao DH, Liu ZX, Zhao G, et al. Rickettsia raoultii, the predominant Rickettsia found in Dermacentor silvarum ticks in China-Russia border areas. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014;63(4):579–85.

Guo LP, Mu LM, Xu J, Jiang SH, Wang AD, Chen CF, et al. Rickettsia raoultii in Haemaphysalis erinacei from marbled polecats, China-Kazakhstan border. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:461.

Sun X, Zhang GL, Liu R, Liu XM, Zhao Y, Zheng Z. Molecular epidemiological study of Rickettsia raoultii in ticks from **njiang, China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2013;34(7):756–57 (in Chinese).

Wang Y, Liu Z, Yang J, Chen Z, Liu J, Li Y, et al. Rickettsia raoultii-like bacteria in Dermacentor spp. ticks, Tibet, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(9):1532–34.

Shpynov S, Fournier PE, Rudakov N, Raoult D. “Candidatus rickettsia tarasevichiae” in Ixodes persulcatus ticks collected in Russia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;990:162–72.

Katargina O, Geller J, Ivanova A, Varv K, Tefanova V, Vene S, et al. Detection and identification of Rickettsia species in Ixodes tick populations from Estonia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6(6):689–94.

Hiraoka H, Shimada Y, Sakata Y, Watanabe M, Itamoto K, Okuda M, et al. Detection of rickettsial DNA in ixodid ticks recovered from dogs and cats in Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67(12):1217–22.

Cheng WY, Zhao GH, Jia YQ, Bian QQ, Du SZ, Fang YQ, et al. Characterization of Haemaphysalis flava (Acari: Ixodidae) from Qingling subspecies of giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca qinlingensis) in Qinling Mountains (Central China) by morphology and molecular markers. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69793.

Jado I, Escudero R, Gil H, Jimenez-Alonso MI, Sousa R, Garcia-Perez AL, et al. Molecular method for identification of Rickettsia species in clinical and environmental samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(12):4572–76.

Regnery RL, Spruill CL, Plikaytis BD. Genotypic identification of rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(5):1576–89.

Liu GP, Ren QM, He SX, Wang F, Yang J. Distribution and medical importance of ticks in three provinces of northeast China. Chin J Hyg Insect & Equip. 2008;14(1):39–42 (in Chinese).

Moyer MW. Tick trouble. Nature. 2015;524(7566):406–08.

Sun Y, Jiang HR, Cao WC, Fu WM, Ju WD, Wang X. Prevalence of Candidatus Rickettsia tarasevichiae-like bacteria in ixodid ticks at 13 Sites on the Chinese-Russian border. J Med Entomol. 2014;51(6):1304–07.

Mediannikov OY, Sidelnikov Y, Ivanov L, Mokretsova E, Fournier PE, Tarasevich I, et al. Acute tick-borne rickettsiosis caused by Rickettsia heilongjiangensis in Russian Far East. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(5):810–17.

Speck S, Derschum H, Damdindorj T, Dashdavaa O, Jiang J, Kaysser P, et al. Rickettsia raoultii, the predominant Rickettsia found in Mongolian Dermacentor nuttalli. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012;3(4):227–31.

Socolovschi C, Mediannikov O, Raoult D, Parola P. The relationship between spotted fever group Rickettsiae and ixodid ticks. Vet Res. 2009;40(2):34.

Matsumoto K, Parola P, Rolain JM, Jeffery K, Raoult D. Detection of “Rickettsia sp. strain Uilenbergi” and “Rickettsia sp. strain Davousti” in Amblyomma tholloni ticks from elephants in Africa. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:74.

Palomar AM, Portillo A, Crespo A, Santibanez S, Mazuelas D, Oteo JA. Prevalence of ‘Candidatus Rickettsia vini’ in Ixodes arboricola ticks in the North of Spain, 2011–2013. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:110.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–29.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Science & Technology Pillar Program during the Twelfth Five-year Plan Period (2013BAD12B04), the Military Medical Health project in China (13CXZ024), the National Key Research Program during the Thirteenth Five-year Plan Period (2016YFC1201602) and the Science and Technology Basic Work Program from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2013FY113600). The funders of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the paper. The corresponding authors had access to the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in the article and its Additional files 1 and 2. Sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under accession numbers KT899076–KT899091 and KX305956–KX305958.

Authors’ contributions

Project designing: QL, SW and ZW; sample collection: QL, ZL and MS; data acquisition: HL, XZ, SW, ZL and Q-HL; data analysis: QL, SW, ZW, FW and Q-HL; manuscript preparation: SW and QL; manuscript revision: QL, SW, FW, MS and Q-HL. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Ticks and tick-borne Rickettsia spp. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Phylogenetic analysis of the partial ompA (533 bp) sequences obtained in this study. Targeted fragments of ompA gene of all of the positive samples were analyzed through the Maximum Likelihood method using MEGA 6.0 [40]. Phylogenic tree was tested by bootstrap** (1000 pseudoreplicates). Sequences in the tree are identified by sample number, tick species, and sampling site. (TIF 5444 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Li, Q., Zhang, X. et al. Characterization of rickettsiae in ticks in northeastern China. Parasites Vectors 9, 498 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1764-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1764-2