Abstract

Background

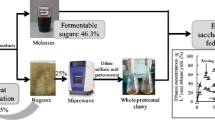

The mixed-feedstock fermentation is a promising approach to enhancing the co-generation of cellulosic ethanol and methane from sugarcane bagasse (SCB) and molasses. However, the unmatched supply of the SCB and molasses remains a main obstacle built upon binary feedstock. Here, we propose a cellulose–starch–sugar ternary waste combinatory approach to overcome this bottleneck by integrating the starch-rich waste of Dioscorea composita Hemls. extracted residue (DER) in mixed fermentation.

Results

The substrates of the pretreated SCB, DER and molasses with varying ratios were conducted at a relatively low solids loading of 12%, and the optimal mixture ratio of 1:0.5:0.5 for the pretreated SCB/DER/molasses was determined by evaluating the ethanol concentration and yield. Nevertheless, it was found that the ethanol yield decreased from 79.19 ± 0.20 to 62.31 ± 0.61% when the solids loading increased from 12 to 44% in batch modes, regardless of the fact that the co-fermentation of three-component feedstock was performed under the optimal condition defined above. Hence, different fermentation processes such as fed-batch and fed-batch + Tween 80 were implemented to further improve the ethanol concentration and yield at higher solids loading ranging between 36 and 44%. The highest ethanol concentration of 91.82 ± 0.86 g/L (69.33 ± 0.46% of theoretical yield) was obtained with fed-batch + Tween 80 mode during the simultaneous saccharification and fermentation at a high solids loading of 44%. Moreover, after the ethanol recovery, the remaining stillage was digested for biomethane production and finally yielded 320.72 ± 6.98 mL/g of volatile solids.

Conclusions

Integrated DER into the combination of SCB and molasses would be beneficial for ethanol production. The co-generation of bioethanol and biomethane by mixed cellulose–starch–sugar waste turns out to be a sustainable solution to improve the overall efficacy in biorefinery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Today, the world’s transport system is still heavily dependent upon fossil fuels supply despite the rapid growth of alternative technologies such as electric vehicles (EVs), compressed natural gas (CNG) cars or biofuels including both bioethanol and biodieselFootnote 1 [1]. The use of fossil fuels has brought about a series of problems, such as environment concerns, depletion of conventional crude oil reserves and regional conflicts of resource control [2, 3]. Biofuels, as alternative energy resources, can relieve those constraints, of which bioethanol plays an important role and accounts for more than 90% of total biofuel utilization [4, 5]. IPCC (2018) has clearly indicated the necessity of transitioning world energy system rapidly to the negative emissions pathways to achieve the global 1.5–2 °C target by the middle of the twenty-first centuryFootnote 2 [6], wherein biofuels are destined to play an increasingly important role in decarbonizing the transport sector over the next decades [7]. This is particularly relevant in many develo** countries such as China who are faced with a double challenge of ensuring food and energy security. Currently, nearly 70% of Chinese oil consumption depends on imports and over half of them goes to the transport sector in 2017 [1, 8]. There is thus an urgent need to accelerate domestic noncrop resources-based bioethanol and biofuel production technologies in the nation.

China has introduced a series of biofuel targets and relevant policy support since 2001, such as the production of bioethanol and utilization of E10 automobile fuel, and has become the third largest producer and consumer of bioethanol, just behind the USA and Brazil [9, 10]. However, bioethanol production based on food crops is being widely criticized since it causes the diversion of edible crops and the increase in food prices [11, 12]. The development of noncrop-based feedstock for bioethanol production has been considered an urgent policy agenda by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the main body of China’s energy policy making [13]. Currently, lignocellulosic bioethanol production has aroused great research interest as the feedstocks are cheap and abundant while avoiding the competition with food sources [14, 15]. However, the commercial production of bioethanol still remains at a nascent stage due to high enzyme costs and low efficacy of generation (both titers and yields) [16].

More recently, the concept of mixed feedstocks, i.e., combining two or more different substrates, has been proposed and investigated to improve the production of lignocellulosic ethanol [3]. The selection of substrates should be based on the requirement of avoiding extra nutrient supplementation, the proximity of the different feedstocks to the collection center or processing facility, and the overall economic viability in term of the relative abundance and low cost of feedstock [3, 17]. Moreover, the selection of mixture components in the current literature mainly referred to the combinations of diverse lignocellulosic biomass or the integration of sugar and or starch-based component into lignocellulosic feedstock [18]. The mixture of different lignocellulosic materials has been researched by combining the substrates classified either as the same category (e.g., mixed hardwood [19], grasses mixtures [20]) or different category (sugarcane bagasse + sugarcane straw [21], rice straw + wheat bran [22]). Meanwhile, the integration of sugar or starch-based component into lignocellulosic ethanol production has also been investigated, wherein the mix component included first-generation biomass feedstock (e.g., wheat meal [23], corn kernel [24]) and starch/sugar-rich waste (e.g., Dioscorea composita Hemls. extracted residue (DER) [25], molasses [26]). This process allows us to reduce the production cost and to increase the lignocellulosic ethanol generation [27].

Our previous work [26] integrated molasses into SCB-based ethanol production which enhanced final ethanol generation and demonstrated that the optimal ratio of sugarcane bagasse and molasses for fermentation was 1:1. Nevertheless, the annual productions of molasses and sugarcane bagasse (SCB) in China’s sugar industry is 4 million and 36 million tons, respectively [28]. This output ratio discrepancy makes molasses incapable of meeting the requirement of SCB-based bioethanol production. To overcome this feedstock imbalance issue, cassava and DER are considered to replace a part of the molasses because they are both starch rich and cultivated worldwide in subtropical and tropical regions. However, cassava, as one of the main materials for starch production in industry, is also consumed as staple food in some regions such as South Asia and Latin America [29], which therefore rules out its large application for biofuel production as feedstock.

So, this paper attempts to integrate DER, a starch-rich supplement, into the combination of SCB and molasses for ethanol production, as D. composita Hemls., a robust energy and medicine plant adapted to local climate and soils in southern China, can be grown at large scale and processed with sugarcane in the same region, and its abundant DER can be easily harvested with SCB at the same time [25]. The three feedstocks can serve as ideal substrates for bioethanol generation due to their advantages of guaranteed availability (they are abundant carbohydrates which can be produced and collected at the same place) and accessibility at low cost (industry waste).

As an abundant and renewable lignocellulosic biomass, SCB is mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin; the latter has been identified as the major factor of inhibiting cellulase hydrolysis, due to its irreversible and non-productive adsorption to cellulase [30]. To effectively remove the recalcitrant component, alkali pretreatment was carried out to disrupt the ether and ester bonds in the lignin units and break the linkages among lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose [31].

The simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) have been widely used to reduce the operational process and cost. In addition, high solids loading fermentation was employed to gain higher ethanol concentration (≥ 40 g/L) and meet the economic production requirement [32]. However, some technical challenges were also brought about with high biomass loading, such as the difficulties of stirring and mixing, the limitation of mass transmission, and the prolonged fermentation time [33]. Fed-batch mode has been proved to hold a good potential for solving those difficulties and improving the ethanol production. Moreover, previous literature indicated that supplementing Tween 80 presented positive influence on the enzymatic hydrolysis and SSF fermentation process [33]. Several studies of combining Tween 80 with SSF had been applied to increase ethanol production [25, 34]; however, the comparison of three modes of batch, fed-batch, and fed-batch + Tween 80 at high solids loading with SSF has rarely been reported.

The sequential production of bioethanol and biomethane proposed in this study has been employed as a sustainable approach given that it can generate higher energy yields compared with a single product, while minimizing the environmental impacts caused by the stillage in the ethanol production [35, 36]. Biomethane production by anaerobic digestion is a complex process, which is significantly influenced by substrate characteristics, fermentation condition, and equipment design [37]. Therefore, materials with a high organic content, optimal pH level, and temperature as well as favorable anaerobic environment were necessary to meet the nutritional requirement of the microbes during the entire production process. Also, the high content of organic matter in the distilled waste feedstocks generated during the ethanol production can be successfully degraded by bacteria, which is conducive to the increase in bioethanol output. In most of the previous studies, the remaining residues following the ethanol recovery were applied to anaerobic digestion to generate environmental benefits such as a significant reduction of COD (around 70–95%).

In this article, DER is used to replace a part of molasses to satisfy the molasses/SCB ratio requirement for ethanol production. This new framework of noncrop plant and biomass waste-based feedstock mixture is then applied to ethanol production and methane recuperation. The optimal designs are characterized by ternary mixed feedstock combinations of DER, SCB, and molasses. After evaluating the optimal ratio of dilute alkali-pretreated SCB, molasses, and DER at a relatively low solids loading of 12%, the co-fermentation of ternary mixed feedstocks with the optimal ratio was performed at solids loading from 12 to 44% in batch mode. Furthermore, batch, fed-batch, and fed-batch + Tween 80 with SSF were performed to assess a more efficient ethanol conversion at higher solids loading (> 32%). Specifically, the stillage was subsequently digested for biomethane production as an effective way to improving the overall efficiency of the biorefinery.

Results and discussion

Chemical analysis of materials

As shown in Table 1, molasses, as the sugar-rich residue of sugar processing, contained 9.02 ± 0.40% fructose, 6.04 ± 0.20% glucose, and 23.04 ± 0.70% sucrose (w/w). DER used in this study is mainly composed of 9.81 ± 0.21% of cellulose, 44.70 ± 0.56% of starch, 15.10 ± 0.11% of xylan, and 11.02 ± 0.52% of acid-insoluble lignin (AIL). The cellulose in pre-saccharified DER was also hydrolyzed to produce ethanol due to the existing cellulase in the co-fermentation condition. The raw SCB mainly consisted of 37.93 ± 0.43% cellulose, 23.25 ± 0.33% xylan, 26.03 ± 0.21% AIL, and 6.34 ± 0.31% acid-soluble lignin (ASL). After dilute alkali pretreatment, the lignin (including AIL and ASL) content in the remaining solids decreased to 10.05 ± 0.05% and 4.01 ± 0.03%, whereas the contents of cellulose and xylan in pretreated SCB increased to 53.01 ± 0.70% and 29.36 ± 0.30%, respectively. The delignification during dilute alkali pretreatment would break down the intact structure of raw SCB, and the decreased content of lignin would reduce the enzymolysis barrier caused by lignin. Meanwhile, these changes would make cellulose partially exposed to enzyme and present a positive effect on the enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation [38].

The experiment of optimizing mix ratios of feedstocks on SSF

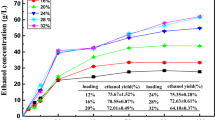

To overcome the ratio imbalance of molasses and SCB output during sugar processing, this study integrated DER into the ethanol production of SCB and molasses. Determining the appropriate materials ratio is necessary to make it better applied into the process of high solids fermentation. Firstly, to increase the input of SCB, the ratios of pretreated SCB/DER/molasses were set at 1:0.5:0.5, 2:0.5:0.5, 3:0.5:0.5, 4:0.5:0.5, and 5:0.5:0.5 (dry weight) with a solid loading of 12%. Figure 1 shows the ethanol concentration at different fermentation times and ethanol yield at the end of fermentation (120 h). The change of all ethanol concentrations has a similar trend that sharply increased in the first 24 h then rose gradually to steady until 120 h. Because the fermentable sugar obtained from molasses and pre-saccharified DER in the slurry can be directly fermented by the yeast, significant differences of fermentation rates were found in the initial 12 h between the control and the mixtures. Compared to single SCB fermentation, the addition of DER and molasses can accelerate the rate of ethanol formation, especially in the first 12 h. High fermentation rates for the mixtures during the first 12 h (1.33–1.66 g/L/h) were observed, whereas the control of pure pretreated SCB showed slow ethanol productivity of only 0.99 g/L/h at the same time. The ethanol production became slow after 24 h and the final ethanol concentrations from 28.89 ± 0.32 to 26.76 ± 0.24 g/L were achieved for the ratio of 1:0.5:0.5, 2:0.5:0.5, 3:0.5:0.5, 4:0.5:0.5, and 5:0.5:0.5 (pretreated SCB/DER/molasses), respectively. Meanwhile, fermentation concentration of 26.19 ± 0.39 g/L could be obtained from pure SCB. The highest ethanol concentration (28.89 ± 0.32 g/L) and yield (79.19 ± 0.20%) were obtained with the ratio of 1:0.5:0.5 for pretreated SCB/DER/molasses. This may be explained by the fact that starch was easier to be hydrolyzed than cellulose, and a greater amount of molasses and pre-saccharified DER provided more favorable nutrients for the yeast growth and fermentation [39]. Moreover, further experiment should be conducted to optimize the appropriate proportion of DER and molasses.

Based on the ratio of 1:0.5:0.5 for pretreated SCB/DER/molasses, a greater amount of pre-saccharified DER was used to replace molasses with the ratio of 1:0.5:0.5, 1:0.6:0.4, 1:0.7:0.3, 1:0.8:0.2, 1:0.9:0.1. As shown in Fig. 1b, the fermentation rate increased with the greater amounts of molasses, because the fermentation of fermentable sugar in molasses is usually faster and can be completed within 24 h. However, the saccharification of starch and cellulosic hydrolysis from DER requires longer time. Although significant differences could not be found among the ethanol concentrations, the ethanol yield was significantly increased when a greater amount of molasses was added [26]. These results were attributed to the higher sugar content from the starch and cellulose in DER. As a result, the optimal ratios of 1:0.5:0.5 for the pretreated SCB/DER/molasses were determined based on the highest ethanol concentration and yield.

The experiment of increasing ethanol concentration at high solids loading

Fermentation with high solids loading was an effective way to increase ethanol concentration [40], hence, in this section, different substrates loading of 12–44% with the optimal ratio of 1:0.5:0.5 for the pretreated SCB/DER/molasses were investigated to explore their influence on SSF. Figure 2 depicts the time course of ethanol concentration and a final ethanol yield after 120 h during SSF. As shown, solids loading of substrates presented an obvious influence on ethanol productivity. It was observed that all ethanol titers increased sharply in the first 24 h and then slowly rose to the highest value. At the low solids loading from 12 to 24%, the ethanol concentration exhibited insignificant variations after 24 h. However, when solids loading were increased from 28 to 44%, it needed more time (120 h) to produce ethanol because high sugar content would take more time for yeast to convert into ethanol [25]. Furthermore, the fermentation rate increased as the increment of solid loading at 12 h reached the highest rate of 3.25 g/L/h with 32% solids loading. However, when the solid loading exceeded 32%, the fermentation rate started to decline instead of increasing further. It can be concluded that the limited system liquidity at a high solid loading led to inadequate stir and ineffective hydrolysis and fermentation at the initial time. Similar findings have been reported in previous literature [25, 41].

The final ethanol concentrations with 12–44% solids loading was 28.89 ± 0.32 g/L, 35.98 ± 0.96 g/L, 43.86 ± 0.39 g/L, 52.24 ± 0.44 g/L, 63.04 ± 1.40 g/L, 68.84 ± 0.21 g/L, 72.55 ± 0.96 g/L, 77.20 ± 0.40 g/L, and 80.56 ± 0.84 g/L, respectively. When the solid loading was over 16%, the ethanol concentrations were higher than 40 g/L, reaching the economical distillation titers. However, the ethanol yield decreased from 79.19 ± 0.20 to 62.31 ± 0.61% for 12–44% solids loading, indicating that many substrates could not be utilized during high solids fermentation. A low ethanol yield with high solids loading could be explained by the low hydrolytic efficiency of cellulase due to non-productive adsorption on lignin and decreased sensitivity of yeast because of the accumulation of inhibitors at high solids loading [42]. Although ethanol concentration significantly increased with an increasing solid loading, the final ethanol yield decreased when more substrates were used into fermentation in batch mode, which made the process costs increase and the economic efficiency reduce [43]. Hence, it was necessary to discuss the influence of different fermentation experiments (fed-batch and fed-batch + Tween 80) on ethanol concentration and yield.

The experiment of improving ethanol concentration and yield at high solids loading

Fed-batch mode is considered as a favorable way to increase cell contents and facilitate the ethanol concentration accumulation [44, 45]. The fed-batch and fed-batch + Tween 80 have been chosen as an instrument to conduct the following experiments of gradually feeding biomass into the fermentation tank to reduce the above-mentioned negative effect of batch mode at high solids loading. During fed-batch SSF, the feeding mode of substrates, yeast, and enzymes have great effect on the entire reaction process. Liu et al. found that all the addition of yeast at the beginning of SSF achieved higher ethanol productivity [46]. Gao et al. evaluated that all cellulase added at 0 h was more favorable to the fermentation process [47]. In this study, all enzymes and yeast were added at the start of SSF and the optimal substrates feeding methods are shown in Table 2. Because pre-saccharified DER required a certain amount of water, partial SCB and all DER were added at 0 h to make a minimum initial solid loading. With the initial solids loading of 21.2%, 22.9%, and 24% for the solids loading of 36% (Fig. 3a), 40% (Fig. 3b) and 44% (Fig. 3c), respectively, the fermentation rates were higher than that of batch mode at the first 8 h due to the increment of system liquidity and exposing more available catalytic sites [48].

However, the ethanol concentration did not show significant differences between the batch mode and fed-batch mode with solids loading of 36%, 40% and 44% at 24 h, it may be explained that the substrates fed has not be completed and the fermentation system have not reached the final solids loading before collected samples were determined at 24 h. There was a significant increase of fed-batch mode compared with batch mode after 24 h, because the addition of molasses at 24 h showed superior fermentation efficiency in fed-batch mode and insufficient mixing and deficient enzymatic accessibility sites in batch mode. Thereafter, the ethanol titers increased gradually until 120 h and the final ethanol concentrations were 72.55 ± 0.96 g/L (75.55 ± 1.22 g/L), 77.20 ± 0.40 g/L (80.69 ± 1.62 g/L), and 80.56 ± 0.84 g/L (86.33 ± 1.49 g/L) for the batch (fed-batch) mode at the solids loading of 36%, 40% and 44%, respectively. The ethanol yields were improved from 66.90 ± 0.36 to 69.61 ± 0.66% (36% of solids loading), 64.10 ± 0.32% to 67.02 ± 0.71% (40% of solids loading), and 62.31 ± 0.61% to 65.22 ± 0.70% (44% of solids loading), respectively. During the fed-batch process, the solid loading was always kept in low condition, leading to the high ratio of cellulase and yeast to substrates, which improved the ethanol concentration and yield.

Tween 80 as a kind of surfactant was added to the fed-batch SSF to further improve the fermentation efficiency [49]. The feeding method of fed-batch + Tween 80 was the same as that for the mode of fed-batch except for the addition of Tween 80 (100 mg/g substance) at the beginning of the experiment, and the fermentation results are shown in Fig. 3. Their fermentation rates were higher than those of the fed-batch and batch mode in the total fermentation process; this phenomenon can be explained intwo ways: the first was Tween 80 could reduce the surface tension of the liquid and thus increase the reactive contact between substances; the second was the combination of Tween 80 and lignin could reduce the unproductive absorption of lignin on cellulase [49]. The final high ethanol concentrations of 80.56 ± 0.84 g/L, 86.33 ± 1.49 g/L and 91.82 ± 0.86 g/L were achieved at the loading of 36%, 40% and 44%, respectively. Although the ethanol concentration increased gradually from 36 to 44%, the ethanol yield decreased from 72.43 ± 0.47 to 69.33 ± 0.46%. This is likely to be the accumulation of by-production and the non-productive adsorption at a higher solids loading [26, 42]. Compared to the batch mode, the fed-batch + Tween 80 mode could generate the highest ethanol concentration of 91.82 ± 0.86 g/L with conversion yield of 69.33 ± 0.46%. It could be concluded that fed-batch + Tween 80 was an efficient way to improve the ethanol productivity at high solids loading fermentation process.

The experiment of anaerobic digestion of the residual stillage

The experiment of biomethane production was continuously conducted after recovering ethanol by evaporation in fed-batch + Tween 80 mode at 44% solids loading. Previous literature reported that the residual sugars and some fermentation by-products were popular for the inoculum to convert methane [36, 50]. As shown in Fig. 4a, the inoculum showed a good methanogenic activity which was deduced from the positive control experiment using microcrystalline cellulose as the substrate with BMP value of 315.65 ± 5.35 mL/g VS. It was observed that the maximum methane yield of 320.72 ± 6.98 mL/g VS was produced after 30 days of digestion from the residual stillage. Similarly, our previous research evaluated the sequential biofuel production by integrating molasses into sugarcane bagasse and obtaining 312.14 mL/g VS methane. A higher methane productivity was achieved in this study because of the three ternary mixture characteristics and relatively low ethanol fermentation efficiency, which left more residual organic contents. In addition, in the fermentation process, the NH3-N values of experimental, control, and blank groups were steady, and they were between the range of (500 and 700) mg/L, which will not inhibit the production of methane in Fig. 4b [51]. The final COD removal efficiency of 82.14 ± 0.75% with an initial concentration of 20,000 mg/L and VS degradation yield of 94.30 ± 0.63% further suggested that most of the fermentation residuals could be converted to biomethane.

It was reported that every liter ethanol produced would generate 7.8 L of stillage [50]. These vinasse can be treated by incineration or conversion into animal feed [52]. However, this method of incineration would generate more cost and energy consumption due to the high content of moisture. Conversion into animal feed cannot match the required protein and fiber content. Therefore, the anaerobic digestion of stillage was developed as an efficient and environmentally friendly method. The combined experiments of bioethanol and biomethane were also performed in a final 1 L of total liquor volumes at 44% of total solids loading to analyze the feasibility of cellulose to glucose to ethanol conversion, apparent viscosity, and the production of biofuel thermal value. For the 1 L liquor volume experiment, the thermal value obtained from the generated ethanol of 90.83 g was 2724.90 kJ, and the produced 37.19 L methane released 1335.12 kJ based on the heat values of ethanol (30.0 kJ/g) and methane (35.9 kJ/L) [36]. Comparative research of biofuel (bioethanol and methane) co-production from different substrates based on high solids fermentation has been summarized in Table 3. Overall, the results obtained in this study lie in the same range as those found in other studies. It was observed that higher energy values were achieved in the co-production process than ethanol fermentation alone. This indicated that sequential biofuel co-production would be a more favorable alternative for comprehensive utilization of biomass.

Conclusions

This article used the starch-rich waste of D. composita Hemls. to substitute a part of molasses to improve SCB-based ethanol production. The ternary combination of cellulose–starch–sugar waste allows overcoming the unmatched supply of molasses and SCB output during sugar processing. At the optimal ratio of 1:0.5:0.5 for the pretreated SCB/DER/molasses, the solids loading was adjusted from 12 to 44% to increase the final ethanol concentration in batch mode. However, the ethanol yield (in terms of ratio of real output to theoretical yield) declined due to the limited system liquidity under high solids loading. Fed-batch and fed-batch + Tween 80 (100 mg/g substance) were applied to further improve the ethanol concentration and yield at higher solids loading ranging between 36 and 44%. Applying Tween 80 to gradual feeding of substrates allowed the ethanol production efficiency to increase as a result of the moderating effect of yeast sensitivity to high concentrated sugars and system viscosity at high solids loading (> 32%). The maximum ethanol concentration of 91.82 ± 0.86 g/L with a theoretical yield of 69.33 ± 0.46% was obtained after 120 h fermentation under fed-batch + Tween 80 mode. After distillation, the residual stillage was converted to methane by anaerobic digestion, and daily methane production reached a plateau a week after and generated an accumulative yield of 320.72 ± 6.98 mL/g VS for 30 days. In conclusion, the technical roadmap of multi-feedstock biofuels production proposed in the present research has significantly improved the bioethanol generation efficiency by increasing ethanol concentration. It can also overcome the obstacles of low solids loading associated with single raw material and insufficient proportion between SCB and molasses during the co-fermentation process. Furthermore, co-generation of bioethanol and biomethane provides a new perspective of achieving higher energy efficiency and product diversity in industry-scale biomass resources utilization.

Methods

Materials

The SCB, molasses, and DER were all obtained from Maoyuan Sugar Co., Ltd., in Shaoguan, Guangdong, China. Pre-milled and screened (< 1 mm lengths) SCB was stored at room temperature, and molasses was kept in a refrigerator at 4 °C. The chemical composition contents of raw and pretreated SCB were analyzed according to the method developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [53]. The starch content of DER was determined by a two-step enzymatic hydrolysis method with 20% dry matter after drying at 60 °C for 12 h: liquefaction using amylase enzyme with 150 U/g dry matter (DM) at 85 °C, pH 5.5, for 3 h and saccharification using glucoamylase with 20 U/g DM at 60 °C, pH 4.5, for 24 h [23]. After the enzymatic hydrolysis, the glucose in the supernatant was analyzed using HPLC and the other compositions in the solid residue were determined using the previously mentioned method provided by NREL [53].

Cellulase (Cellic CTec2) with an activity of 164 FPU/mL was used for SSF according to the methods provided by NREL [54].

The Saccharomyces cerevisiae used during SSF was provided by Angel Yeast Co., Ltd. (Yichang, China).

Alkaline pretreatment

Alkaline pretreatment was carried out in a round-bottom flask. The weighted biomass samples were pretreated by 0.5 mol/L NaOH at 80 °C for 2 h with a solid/liquid ratio of 1:20. After pretreatment, the liquor and residues in the slurry were separated by vacuum filtration and the residues were washed until a neutral pH. The pretreated SCB was then subject to composition analysis and SSF after dried at 50 °C for 48 h.

Pre-saccharification

The weighted DER mixed with deionized water at 250 g/L (w/v) was preheated to 85 °C when the pH was adjusted to 5.5. Meanwhile, 150 U/g DER of liquefying enzyme was added into the DER slurry for 2 h with 120 rpm. Then, when the temperature of mashes was cooled to 60 °C, the saccharification was conducted by using amyloglucosidase (20 U/g DER) for 2 h before the pH of the slurry was adjusted to 4.5.

Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF)

During the SSF process, various mixtures of calculated weight of alkali-pretreated SCB, DER, and molasses were added into a 250 mL flask under 4.5 pH (adjusted by 1.0 mol/L of sulfuric acid). Before SSF, the inoculated yeast of 6.6 g was firstly activated at 36 °C for 10 min and 34 °C for 60 min in a 2% glucose solution (100 mL) at 120 rpm. 5 mL of activated yeast and 15 FPU/g pretreated SCB of the cellulase were then injected to the reaction system and finally a specified volume of sterile water was supplied to reach 100 mL of liquor. All experiments were performed in a sterile environment. Different from the batch mode, the fed-batch mode is conducted by gradually feeding the substrates to achieve final high solid loading. The fed-batch + Tween 80 mode is the same as the fed-batch mode except for the addition of Tween 80 (100 mg/g substance) to the system at the initial time. SSF was conducted in the shaker at 34 °C and 120 rpm for 120 h in triplicate.

Analytical methods

The fermentation sugar content of molasses and saccharified DER was analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatography system (HPLC, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a refractive index detector (RID) and a cation-exchange column (SUGAR KS-801; 300 mm * 8.0 mm; Shodex™, Japan). Ethanol samples were collected periodically and determined by HPLC after centrifugation and purification by 0.22 mm filter. The HPLC uses a refractive index detector (RID) and a cation-exchange column (SUGAR SH1011; 300 mm * 8.0 mm; Shodex™, Japan), and the mobile phase uses 0.05 M H2SO4 with 1.0 mL/min flow rate at 50 °C. In the SSF, the maximal ethanol yield for glucose (0.51 g/g) could be calculated, and 1.11 g of glucose was produced by 1 g of starch or cellulose. The ethanol yield was calculated by the following formula:

Biomethane production

After ethanol was evaporated from the fermentation medium using a rotary evaporator at 60 °C, the non-fermented residues were subjected to biomethane production using Bioprocess Control AMPTS II (Automatic Methane Potential Test System) in triplicate. Anaerobic digestion was performed in 500 mL sealed batch flasks using a 400 mL working volume at 37 °C for 30 days until no gas was detected with a 1:1 based on VS mixture ratio of substrates and inoculum (7.66 g of total VS) [50].

The inoculum used in this experiment was obtained from the Datansha Sewage treatment plant in Guangzhou, China, and cultivated in a mesophilic anaerobic fermentation tank in our laboratory over a long period, which has a characteristic of total solids (TS) 6.74%, volatile solids (VS) 1.00%, and pH 7.3–7.5. Before biomethane production, the inoculum was pre-incubated at 37 °C for 1 week in a starving condition aiming at the reduction of endogenous biomethane production. Then N2 was purged into the bottles for 3–5 min to guarantee anaerobic conditions. Bottles containing pure inoculum as blank samples as well as microcrystalline cellulose and inoculum as control samples were simultaneously determined.

During biomethane production, samples were withdrawn for determining the value of TS, VS, COD, and ammonium nitrogen (NH3-N) based on the previously reported method [55, 56], and pH values were detected by a pH meter (Five Easy Plus, Mettler-Toledo, Australia).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of standard errors and variance use SPSS version 16.0. Significance was analyzed and used when the p value < 0.05.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- SCB:

-

sugarcane bagasse

- DER:

-

Dioscorea composita Hemls. extracted residue

- SSF:

-

simultaneous saccharification and fermentation

- COD:

-

chemical oxygen demand

- HPLC:

-

high-performance liquid chromatography

- RID:

-

Refractive Index Detector

- BMP:

-

biological methane potential

- AMPTS:

-

Automatic Methane Potential Test System

- TS:

-

total solid

- VS:

-

volatile solid

- AIL:

-

acid-insoluble lignin

- ASL:

-

acid-soluble lignin

References

Agency IE. World energy outlook. Paris: OECD; 2018.

Ge Y, Li L. System-level energy consumption modeling and optimization for cellulosic biofuel production. Appl Energy. 2018;226:935–46.

Oke MA, Annuar MSM, Simarani K. Mixed feedstock approach to lignocellulosic ethanol production—prospects and limitations. Bioenergy Res. 2016;9:1–15.

Shanavas S, Padmaja G, Moorthy SN, Sajeev MS, Sheriff JT. Process optimization for bioethanol production from cassava starch using novel eco-friendly enzymes. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011;35:901–9.

Caspeta L, Caro-Bermúdez MA, Ponce-Noyola T, Martinez A. Enzymatic hydrolysis at high-solids loadings for the conversion of agave bagasse to fuel ethanol. Appl Energy. 2014;113:277–86.

Lawrence MG, Schäfer S. Promises and perils of the Paris agreement science. Science. 2019;364:829–30.

IPCC. Global warming of 1.5 °C: summary for policymakers. Geneva: IPCC; 2018.

Statistics NBo. China statistical yearbook 2018; 2019.

Ding N, Yang Y, Cai H, Liu J, Ren L, Yang J, et al. Life cycle assessment of fuel ethanol produced from soluble sugar in sweet sorghum stalks in North China. J Clean Prod. 2017;161:335–44.

Xu X, Yang Y, **ao C, Zhang X. Energy balance and global warming potential of corn straw-based bioethanol in China from a life cycle perspective. Int J Green Energy. 2018;15:296–304.

Ghosh S, Chowdhury R, Bhattacharya P. Sustainability of cereal straws for the fermentative production of second generation biofuels: a review of the efficiency and economics of biochemical pretreatment processes. Appl Energy. 2017;198:284–98.

Banerjee S, Mudliar S, Sen R, Giri B, Satpute D, Chakrabarti T, et al. Commercializing lignocellulosic bioethanol: technology bottlenecks and possible remedies. Biofuels Bioprod Biorefin. 2010;4:77–93.

Liu H, Huang Y, Yuan H, Yin X, Wu C. Life cycle assessment of biofuels in China: status and challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;97:301–22.

Dong C, Wang Y, Chan K-L, Bhatia A, Leu S-Y. Temperature profiling to maximize energy yield with reduced water input in a lignocellulosic ethanol biorefinery. Appl Energy. 2018;214:63–72.

Cripwell R, Favaro L, Rose SH, Basaglia M, Cagnin L, Casella S, et al. Utilisation of wheat bran as a substrate for bioethanol production using recombinant cellulases and amylolytic yeast. Appl Energy. 2015;160:610–7.

Menon V, Rao M. Trends in bioconversion of lignocellulose: biofuels, platform chemicals & biorefinery concept. Prog Energy Combust Sci. 2012;38:522–50.

Kim KH, Tucker M, Nguyen Q. Conversion of bark-rich biomass mixture into fermentable sugar by two-stage dilute acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. Biores Technol. 2005;96:1249–55.

Baxter L. Biomass-coal co-combustion: opportunity for affordable renewable energy. Fuel. 2005;84:1295–302.

Lim WS, Lee JW. Effects of pretreatment factors on fermentable sugar production and enzymatic hydrolysis of mixed hardwood. Biores Technol. 2013;130:97–101.

Martín C, Thomsen MH, Hauggaard-Nielsen H, Belindathomsen A. Wet oxidation pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis and simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of clover-ryegrass mixtures. Biores Technol. 2008;99:8777–82.

Moutta RDO, Ferreira-Leitão VS, Bon EPDS. Enzymatic hydrolysis of sugarcane bagasse and straw mixtures pretreated with diluted acid. Biocatalysis. 2014;32:93–100.

Qi B, Yao R, Yu Y, Chen Y. Influence of different ratios of rice straw to wheat bran on production of cellulolytic enzymes by Trichoderma viride ZY-01 in solid state fermentation. Elec J Environ Agric Food Chem Title. 2007;6:2341–9.

Erdei B, Barta Z, Sipos B, Réczey K, Galbe M, Zacchi G. Ethanol production from mixtures of wheat straw and wheat meal. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2010;3:16.

Tang Y, Zhao D, Cristhian C, Jiang J. Simultaneous saccharification and cofermentation of lignocellulosic residues from commercial furfural production and corn kernels using different nutrient media. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2011;4:22.

Ye G, Zeng D, Zhang S, Fan M, Zhang H, **e J. Ethanol production from mixtures of sugarcane bagasse and Dioscorea composita extracted residue with high solid loading. Biores Technol. 2018;257:23.

Fan M, Zhang S, Ye G, Zhang H, **e J. Integrating sugarcane molasses into sequential cellulosic biofuel production based on SSF process of high solid loading. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:329.

Xu Y, Wang D. Integrating starchy substrate into cellulosic ethanol production to boost ethanol titers and yields. Appl Energy. 2017;195:196–203.

Na Y, Li T, Sun ZY, Tang YQ, Kida K. Production of bio-ethanol by integrating microwave-assisted dilute sulfuric acid pretreated sugarcane bagasse slurry with molasses. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2017;185:1–16.

Luo H, Li Y, Sun Z, Liang K, Xu W, Lai M. Optimization of fermentation for fuel ethanol production from cassava. Chin J Bioprocess Eng. 2018;16:80–5.

Wang W, Tan X, Yu Q, Wang Q, Qi W, Zhuang X, et al. Effect of stepwise lignin removal on the enzymatic hydrolysis and cellulase adsorption. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;122:16–22.

Li HY, Chen X, Wang CZ, Sun SN, Sun RC. Evaluation of the two-step treatment with ionic liquids and alkali for enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis of Eucalyptus: chemical and anatomical changes. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2016;9:166.

Xu F, Sun J, Konda NVSNM, Shi J, Dutta T, Scown CD, et al. Transforming biomass conversion with ionic liquids: process intensification and the development of a high-gravity, one-pot process for the production of cellulosic ethanol. Energy Environ Sci. 2016;9:1042–9.

Modenbach AA, Nokes SE. The use of high-solids loadings in biomass pretreatment—a review. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:1430–42.

Tsuji M, Yokota Y, Kudoh S, Hoshino T. Improvement of direct ethanol fermentation from woody biomasses by the Antarctic basidiomycetous yeast, Mrakia blollopis, under a low temperature condition. Cryobiology. 2014;68:303–5.

Fuess LT, Garcia ML. Anaerobic digestion of stillage to produce bioenergy in the sugarcane-to-ethanol industry. Environ Technol. 2014;35:333–9.

Kalyani DC, Zamanzadeh M, Müller G, Horn SJ. Biofuel production from birch wood by combining high solid loading simultaneous saccharification and fermentation and anaerobic digestion. Appl Energy. 2017;193:210–9.

Divya D, Gopinath LR, Christy PM. A review on current aspects and diverse prospects for enhancing biogas production in sustainable means. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;42:690–9.

Alvira P, Tomás-Pejó E, Ballesteros M, Negro MJ. Pretreatment technologies for an efficient bioethanol production process based on enzymatic hydrolysis: a review. Biores Technol. 2010;101:4851–61.

Appiahnkansah NB, Saul K, Rooney WL, Wang DH. Adding sweet sorghum juice into current dry-grind ethanol process for improving ethanol yields and water efficiency. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2015;8:97–103.

Kristensen JB, Felby C, Jørgensen H. Yield-determining factors in high-solids enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2009;2:11.

Koppram R, Tomás-Pejó E, **ros C, Olsson L. Lignocellulosic ethanol production at high-gravity: challenges and perspectives. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32:46–53.

Stenberg K, Bollók M, Réczey K, Galbe M, Zacchi G. Effect of substrate and cellulase concentration on simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of steam-pretreated softwood for ethanol production. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;68:204–10.

Svensson E, Lundberg V, Jansson M, **ros C, Berntsson T. The effect of high solids loading in ethanol production integrated with a pulp mill. Chem Eng Res Des. 2016;111:387–402.

Saarela U, Leiviskä K, Juuso E, Kosola A. Modelling of a fed-batch enzyme fermentation process. In: IFAC international conference on intelligent control systems and signal processing Faro, Portugal, April 8–11;2003.

Zheng Y, Yu C, Cheng YS, Lee C, Simmons CW, Dooley TM, et al. Integrating sugar beet pulp storage, hydrolysis and fermentation for fuel ethanol production. Appl Energy. 2012;93:168–75.

Liu Y, Xu JX, Zhang Y, He M, Liang C, Yuan Z, et al. Improved ethanol production based on high solids fed-batch simultaneous saccharification and fermentation with alkali-pretreated sugarcane bagasse. BioResources. 2016;11:2548–56.

Gao Y, Xu J, Yuan Z, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Liang C. Optimization of fed-batch enzymatic hydrolysis from alkali-pretreated sugarcane bagasse for high-concentration sugar production. Biores Technol. 2014;167:41–5.

Gao Y, Xu J, Yuan Z, Jiang J, Zhang Z, Li C. Ethanol production from sugarcane bagasse by fed-batch simultaneous saccharification and fermentation at high solids loading. Energy Sci Eng. 2018;6:810–8.

** W, Chen L, Hu M, Sun D, Li A, Li Y, et al. Tween-80 is effective for enhancing steam-exploded biomass enzymatic saccharification and ethanol production by specifically lessening cellulase absorption with lignin in common reed. Appl Energy. 2016;175:82–90.

Liu YY, Xu JL, Yu Z, Yuan ZH, He MC, Liang CY, et al. Sequential bioethanol and biogas production from sugarcane bagasse based on high solids fed-batch SSF. Energy. 2015;90:1199–205.

Chen Y, Cheng JJ, Creamer KS. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:4044–64.

Wang TT, Sun ZY, Huang YL, Tan L, Tang YQ, Kida K. Biogas production from distilled grain waste by thermophilic dry anaerobic digestion: pretreatment of feedstock and dynamics of microbial community. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2017;184:1–18.

Sluiter A, Hames B, Ruiz R, Scarlata C, Sluiter J, Templeton D, et al. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Lab Anal Proced. 2008;1617:1–16.

Adney B, Baker J. Measurement of cellulase activities. Lab Anal Proced. 1996;6:1996.

American Public Health Association A. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington: American Public Health Association A; 1998.

Li Y, Zhang R, Chen C, Liu G, He Y, Liu X. Biogas production from co-digestion of corn stover and chicken manure under anaerobic wet, hemi-solid, and solid state conditions. Biores Technol. 2013;149:406–12.

Katsimpouras C, Zacharopoulou M, Matsakas L, Rova U, Christakopoulos P, Topakas E. Sequential high gravity ethanol fermentation and anaerobic digestion of steam explosion and organosolv pretreated corn stover. Biores Technol. 2017;244:1129.

Wang Z, Lv Z, Du J, Mo C, Yang X, Tian S. Combined process for ethanol fermentation at high-solids loading and biogas digestion from unwashed steam-exploded corn stover. Biores Technol. 2014;166:282–7.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the funding support from the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province in China (2017B020238005, 2019B110209003 and 2015B020215011), the National Science and Technology Support Project of China (2015BAD15B03 and 2015BAD21B03), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21606091).

Funding

Funding sources have been addressed in the acknowledgements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MF designed and performed the major experiments and analyzed the results. GB, and GY helped with analyzing the data. MF and JL contributed equally to the manuscript. HZ assisted JX in proofing data and giving guidance for formatting the submission of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All the authors consented to the publication of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, M., Li, J., Bi, G. et al. Enhanced co-generation of cellulosic ethanol and methane with the starch/sugar-rich waste mixtures and Tween 80 in fed-batch mode. Biotechnol Biofuels 12, 227 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1562-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1562-0