Abstract

Background

Adolescents in low- and middle-income countries in need of mental health care often do not receive it due to stigma, cost, and lack of mental health professionals. Culturally appropriate, brief, and low-cost interventions delivered by lay-providers can help overcome these barriers and appear effective at reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety until several months post-intervention. However, little is known about whether these interventions may have long-term effects on health, mental health, social, or academic outcomes.

Methods

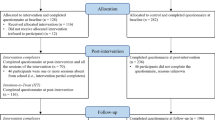

Three previous randomized controlled trials of the Shamiri intervention, a 4-week, group-delivered, lay-provider-led intervention, have been conducted in Kenyan high schools. Shamiri teaches positively focused intervention elements (i.e., growth mindset and strategies for growth, gratitude, and value affirmation) to target symptoms of depression and anxiety and to improve academic performance and social relationships, by fostering character strengths. In this long-term follow-up study, we will test whether these mental health, academic, social, and character-strength outcomes, along with related health outcomes (e.g., sleep quality, heart-rate variability and activity level measured via wearables, HIV risk behaviors, alcohol and substance use), differ between the intervention and control group at 3–4-year follow-up. For primary analyses (Nanticipated = 432), youths who participated in the three previous trials will be contacted again to assess whether outcomes at 3–4-year-follow-up differ for those in the Shamiri Intervention group compared to those in the study-skills active control group. Multi-level models will be used to model trajectories over time of primary outcomes and secondary outcomes that were collected in previous trials. For outcomes only collected at 3–4-year follow-up, tests of location difference (e.g., t-tests) will be used to assess group differences in metric outcomes and difference tests (e.g., odds ratios) will be used to assess differences in categorical outcomes. Finally, standardized effect sizes will be used to compare groups on all measures.

Discussion

This follow-up study of participants from three randomized controlled trials of the Shamiri intervention will provide evidence bearing on the long-term and health and mental health effects of brief, lay-provider-delivered character strength interventions for youth in low- and middle-income countries.

Trial registration

PACTR Trial ID: PACTR202201600200783. Approved on January 21, 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Administrative information

Note: the numbers in curly brackets in this protocol refer to SPIRIT checklist item numbers. The order of the items has been modified to group similar items (see http://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/spirit-2013-statement-defining-standard-protocol-items-for-clinical-trials/).

Title {1} | Long-term health outcomes of adolescent character strength interventions: three-to four-year outcomes of three randomized controlled trials of the Shamiri program |

Trial registration {2a and 2b}. | Pan African Clinical Trials Registry: PACTR202201600200783 |

Protocol version {3} | 1.0 |

Funding {4} | Primary funding for this trial was provided by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, grant #TWCF0633. Secondary funding for this trial was provided by Alchemy Pay. |

Author details {5a} | 1Shamiri Institute, Nairobi, Kenya & Allston, MA, USA 2Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 3Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA 4Competence Center for Empirical Research Methods, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria 5African Mental Health Research & Training Foundation, Nairobi, Kenya 6Department of Psychiatry, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya 7Department of Psychology, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya |

Name and contact information for the trial sponsor {5b} | Templeton World Charity Foundation Phone: 2423624904 |

Role of sponsor {5c} | This study was primarily funded by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, located at Bayside Executive Park, Bldg. #2, West Bay Street and Blake Rd., PO Box N-7776, Nassau, Bahamas. Secondary funding was received from Alchemy Pay, located at Novelty TechPoint 0502, 27 New Industrial Road, Singapore. The study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication are the sole responsibilities of the authors. |

Introduction

Background and rationale {6a}

Recently, there has been increasing recognition of mental health as an essential component of health, with the World Health Organization (WHO) declaring that health cannot exist without mental health [1]. Reports of mental health issues among children and adolescents are increasing globally, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic [2], with around 20% of children and adolescents having a mental health condition, and most mental health disorders originating between the ages of 12 and 24 [3, 4]. Poor mental health is associated with many additional concerns for health and development among young people, including lower educational achievement, substance use problems, risk of experiencing and perpetrating violence, relationship problems, poor reproductive and sexual health, and suicide risk [4,5,6,7,8].

School-going adolescents in many parts of the world, particularly in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) such as those in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), are in urgent need of innovative ways to address mental health burdens, as they face several barriers to accessing care. Such barriers include a dearth of trained mental health clinicians and stigma associated with mental health conditions and care [9, 10]. Additionally, the duration and cost of most mental health treatments—many of which were not designed for use in SSA [11]—are prohibitive to many youths and families [4, 12].

These barriers to care have led researchers to test low-cost, low-stigma, and scalable mental health solutions in SSA, some of which could be considered character strength interventions (i.e., interventions to build character strengths and apply them to one’s life) [13] and wise interventions (i.e., brief, precise interventions targeting specific psychological processes that influence meaning-making about the self and the world) [14]. One intervention drawing from this literature, Shamiri, meaning “Thrive” in Kiswahili, is delivered in a group setting by near-peer high school graduate lay-providers, and is designed to change the way high-school-aged youths view themselves and the world [15, 16]. Shamiri takes four hours to implement over the course of four weeks, and has three components: growth mindset [17] and strategies for growth, gratitude [18], and value affirmation [19].

Previous research on Shamiri in Kenya has shown promising improvements in youth mental health, psychosocial, and academic outcomes at post-intervention and seven-months follow-up [17, 20]. In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of Shamiri with 51 Kenyan adolescents with clinically elevated depression and/or anxiety symptoms, we found improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms, academic performance, and perceived social support from friends when compared to an active study skills control group immediately post-intervention [15]. In a well-powered (N = 413), preregistered replication of this study [16], youths in the Shamiri intervention exhibited improvements in depression and anxiety symptoms over time, and when compared to the active study skills control group. These improvements were maintained at 7 months post-intervention [20]. This study also indicated that Shamiri is feasible and acceptable to Kenyan youths. A third ongoing trial is intended to investigate the effects of each of the three components of the Shamiri intervention against the full Shamiri protocol and an active study skills control group [21].

Our previous work which focused on develo** and testing Shamiri suggests that this short character strength intervention has the potential to improve social, academic, and mental health outcomes of youth in Kenya. An important next step is to evaluate Shamiri’s potential for improving these and other related health outcomes in the long-term. Therefore, in this proposed study, we will investigate the Shamiri intervention’s effects, relative to the active control condition’s effects, on a wider variety of health, wellbeing, and social outcomes at 3–4-year follow-up of participants in our three prior RCTs. To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study to test the effects of character strength interventions on such a rich range of health outcomes over such an extended period.

Objectives {7}

This study has four goals. Our primary goal is to compare the effects of the Shamiri intervention and control condition on the primary outcomes (depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, academic performance, and social support) in the long-term. We hypothesize that the intervention group will outperform the active control on each of our primary outcomes. Secondarily, we aim to compare the effects of each group on secondary outcomes (described below in {12}). We also aim to explore for whom these interventions are most effective in the long-term. Finally, in an exploratory fashion, we wish to compare effects for the intervention groups that received a single component of the Shamiri intervention against the group that received the full Shamiri intervention and the active control group.

Trial design {8}

This study is a parallel-group randomized comparative effectiveness trial with five arms: (1) the Combined Shamiri Intervention (consisting of a growth element, a gratitude element, and a value affirmation element), (2) the Growth Intervention, which encompasses content related to growth mindset and strategies for growth, (3) the Gratitude Intervention, which incorporates content to build feelings of gratitude and expression of gratitude, (4) the Values Intervention, which incorporates content to help students identify, affirm, and better act on their personal values and sense of purpose, and (5) a Study Skills Control, an active control group teaching students study skills that may be useful to them as students. Each condition is described further in section {11a}. All participants in this trial have already completed intervention in these conditions in three previous RCTs. The first and second RCT had two conditions, the Combined Shamiri Intervention, and the Study Skills control, and these interventions were administered with a 1:1 ratio, or equal probability for assignment to each of the two conditions. In the third RCT, participants were allocated within each school to the five conditions with a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio or equal probability for assignment to each of the five conditions. Each arm required 4-h-long sessions spanning 4 weeks and was delivered in a group of 8–15 students by a local lay provider, aged between 18 and 24. Measures of mental health, wellbeing, and character strengths were collected in the three previous RCTs at baseline, 2-week midpoint, 4-week endpoint, and 1-month, 3-month, 7-month, and 9-month follow-up. For this long-term follow-up, measures of mental health, wellbeing, character strengths, stress, health behaviors, socioeconomic and health status will be collected at 3–4 years follow-up. Academic data was collected in the three previous RCTs for the school terms before, during, and immediately after the intervention. For the current trial, academic data will be collected for the last year of secondary school. De-identified trial data will be available upon request.

Methods: participants, interventions, and outcomes

Study setting {9}

This study will be conducted with participants who attended secondary school in Kiambu and Nairobi counties in Kenya. For participants under 18 or still in school, we will visit their schools to conduct data collection. Data collection for adults no longer in school will take place in the Nairobi area at the African Mental Health Research and Training Foundation (AMHRTF) offices. Adult participants will present themselves to AMHRTF for self-reports and assessment by a clinician. These participants will also visit Kenyatta National Hospital’s Voluntary Counselling & Testing Centre if they wish to know their HIV status.

Eligibility criteria {10}

All participants who have taken part in three previous RCTs [15, 20, 21] of the in-person, group-based, 4-week Shamiri intervention, and had elevated symptoms of depression or anxiety at baseline of the previous RCTs (defined as scores of 10 or over on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD) and 15 or over on the Patient Health Questionnaire-8 (PHQ-8)) are eligible for enrolment in this long-term follow-up study. Participant consent or assent, and in the case of minors, guardian consent, will also be required for participation. No additional exclusion criteria will be applied.

Who will take informed consent? {26a}

A member of the study team who is from and living in Kenya will seek informed consent and assent prior to collecting follow-up measures. We will provide participants with a digital consent form (see supplementary materials for the model consent form to be used). Then, a member of the study team with appropriate ethical training and Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval will walk the participants through the consent form and clarify any questions they may have. They will emphasize the voluntary nature of participation in the study.

While we hope to seek permission/consent from parents of minors who wish to participate in our study, following local customs of boarding schools in Kenya, where students do not have direct access to their parents, as well as the logistical difficulty in obtaining written consent from parents disbursed throughout the country with limited access to timely postal communication, we will work with the school administration to obtain consent from the parents of minors. Specifically, we will work with school administrators to obtain informed consent on behalf of parents using the customary methods of the school (i.e., sending text messages or calling parents). The participants who are minors will also be asked to provide informed assent on site.

Additional consent provisions for collection and use of participant data and biological specimens {26b}

We will seek additional consent prior to taking physical measures of health from participants. They will be informed that these measures are voluntary and that they may opt out of them at any time as they wish. We will also seek additional consent from participants over 18 years old who are not in school and wish to attend Kenyatta National Hospital’s Voluntary Counselling & Testing Center for an HIV test and inform participants that if they wish to be tested for HIV, we will pay for the test, and if they wish, they may report the result of the test back to the study team, but that they are not required to do so.

This trial does not involve collection, storage, or analysis of biological specimens.

Interventions

Explanation for the choice of comparators {6b}

For primary analyses, the Shamiri intervention will be compared to a Study Skills active control condition of equal duration and highly similar format. As detailed further in a protocol for one of the three RCTs [21] from which participants will be drawn for this study, the Study Skills active control condition was selected as a comparator for several reasons. First, active control conditions typically provide a more robust comparison than no-treatment or waitlist control conditions [22]. Second, because students in Kenyan high schools report pressure to succeed academically at high rate and severity [23], improving study skills may be practically useful and may help reduce stress and anxiety for students. Third, past research has shown that symptoms of mental health problems may indeed be somewhat alleviated by the Study Skills control condition [15]. Finally, those in the Study Skills control condition participated in weekly small group sessions led by a lay-provider; this regular contact may have helped lower barriers to requesting needed support from a lay-provider.

Intervention description {11a}

Participants in three RCTs have previously completed their participation in the intervention and control conditions. Each condition consisted of four sessions, lasting 1 h per session for a duration of 4 weeks. The intervention and control conditions were delivered by a near-peer lay provider to groups of approximately 8–15 students. Participants will not participate in the intervention or control condition again as part of this study but instead will complete follow-up measures to assess the long-term effects of these interventions. These interventions are further detailed in the intervention descriptions of our previous three RCTs [15, 20, 21]. Each condition consisted of an equal dose of total intervention time: four 1-h weekly sessions that focused on teaching and reinforcing the knowledge and application of the active ingredient of the condition. Each single-element intervention (i.e., growth only, gratitude only, or values only intervention) included the elements related to this one element in the combined Shamiri condition, along with additional related activities to teach and practice the same principles. Sample intervention protocols can be found in the supplementary materials for a previous article on Shamiri [21]. The general format for each intervention was as follows:

-

In session 1, participants completed baseline measures, were introduced to the guidelines for the group and completed group activities to introduce themselves. They learned through educational discussions and simple, fun activities about the scientific literature of their assigned intervention and how the intervention might help them in their life. Session 1 typically ended with a group discussion about the active ingredient.

-

In session 2, participants heard stories and anecdotes related to the active ingredient of their assigned condition. Participants also completed a writing exercise to digest information from this session. Mid-point measures were collected at the end of session 2.

-

In session 3, participants completed evidence-based exercises related to the active ingredient which taught participants how to apply what they have learned to solve real-life problems. Participants were also typically asked to apply these techniques to a hypothetical scenario.

-

Session 4 summarized what participants had learned about the active ingredient through discussion and group activities. Participants completed endpoint measures at the end of this session. The active ingredients which participants were previously randomized to are described below:

Combined Shamiri intervention

Participants who received this condition completed modules related to the active ingredients described below: growth, gratitude, and values. The first two sessions focused on growth mindset, the third session focused on gratitude, and the final session focused on values. These sessions incorporated a mixture of lecture, discussion, and group exercises.

Gratitude intervention only

Some participants received only the gratitude intervention, which taught them how to intentionally notice, communicate, and appreciate feelings of gratitude. Participants also learned how to practice gratitude on a daily basis in their lives. Group leaders emphasized the importance of verbalizing and consciously thinking about what we are grateful for, as well as the benefits this has on wellbeing. Group exercises included how to better express gratitude and incorporate it into everyday life.

Values intervention only

In this condition, participants learned about identifying and living according to their core values. Participants shared their understanding of values with their group and the values that were most relevant to their lives. Participants then chose personal values and wrote about how they have demonstrated those values. They completed activities such as considering how they could live more in accordance with their values, telling stories of inspiring role models, and making goals for applying their values to their lives.

Growth intervention only

Participants who received the growth condition only learned about neuroplasticity, which is the ability of the brain to grow and change over time and with effort. In groups, participants completed activities such as a saying-is-believing exercise, wrote personal growth stories, heard testimonials, and discussed and considered how to apply strategies for solving problems and growing.

Study skills control

This control condition was developed in collaboration with Kenyan experts in research and education. Participants who received this condition learned skills designed to improve abilities to study and ultimately academic performance. As part of this condition, participants learned tips related to skills such as note taking, critical reading, and essay writing, as well as how to implement a “study cycle:” studying throughout the year instead of cramming right before exams.

Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions {11b}

Because no interventions will be delivered during this trial, there are no criteria for discontinuing or modifying interventions. As for the outcome measurement protocol, participants will be informed that they may refuse to answer any questions asked as part of outcome measures collected by the study team and that they may withdraw their consent to participate in the study at any time.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions {11c}

Because no interventions will be delivered during this trial, no strategies for improving adherence to interventions are necessary. As for the outcome measurement protocol, adherence to that will be ensured via extensive training and monitoring of outcome assessors, as detailed under Data Collection and Management below.

Relevant concomitant care permitted or prohibited during the trial {11d}

Participants were not prevented from seeking care outside of the study during the 3–4 years since participating in the Shamiri intervention trials. However, because of a paucity of trained mental health care providers [9] and elevated stigma associated with mental illness and mental health care in Kenya [10], it is unlikely that many participants in the Shamiri trials have received formal mental health care in the years since participating in the Shamiri intervention trials.

Provisions for post-trial care {30}

We do not anticipate harm caused by participating in this study, and thus have no plans for compensation in case of harm. For those participants who present with elevated risk of harm to self or others, or who report need for continued support or care for other reasons (e.g., substance use, abuse, need for essential resources such as food), the study team and primary care clinician will collaboratively implement an emergency protocol (located in supplementary materials) and will provide all adult participants who have completed school with a resource sheet including relevant local resources. For participants who are still minors and/or in school, the study team and primary care clinician will collaborate with guardians including school officials to provide necessary resources and care according to local customs.

Outcomes {12}

As part of the three RCTs from which we will recruit participants for this trial, many of the outcomes below have been previously collected from participants. In each measure below, it is indicated whether it was collected in previous trials. All outcomes below will be collected from participants in this RCT once, at 3–4 years follow-up.

For full details of planned analyses, see {20} below. In addition to these analyses, summary statistics of central tendency (e.g., averages) and measures of dispersion/variability (e.g., standard deviations), and when relevant, 95% confidence intervals for scores of each outcome measure will be calculated and reported.

Primary outcome measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-8

The PHQ-8 will be used to assess the severity of symptoms of depression [24, 25]. PHQ-8 is an 8-item version of the PHQ-9 that excludes the final item which asks about suicidal ideation. Local Kenyan experts, including researchers and school officials, have instructed us to exclude this item due to the stigma associated with suicidal ideation, which could be harmful and off-putting to participating and potential schools and students. PHQ-8 scores have been shown to be highly correlated with PHQ-9 scores; hence, the same scores can be used to determine severity of depression [24, 26]. The PHQ-8 has been used to classify depression among Kenyan adolescents [20, 27, Methods for additional analyses (e.g., subgroup analyses) {20b} In secondary, exploratory analyses, we will compare long-term outcomes in the growth-only, gratitude-only, and sense of purpose-only interventions to long-term outcomes in the control group and in the Shamiri Intervention group. For these analyses, we will use the same model types as described above but using the corrections for multiple testing to keep the family-wise error rate. Additional analyses (e.g., mediator and moderator analyses, or analyses of baseline data) will be conducted in an exploratory fashion rather than as part of main analyses described in this protocol. Such exploratory analyses will be disseminated in separate publications from main analyses. Prior to analysis, univariate, bivariate, multivariate, distributional, and missing data characteristics of the data will be examined, with subsequent models adjusted (e.g., using robust estimators and inference, appropriate error distributions, non-parametric approaches) to ensure data-analytic assumptions are met. Missing item-level data will be accommodated using full information maximum likelihood or multiple imputation methods if the assumption (missing at random; MAR) for these mitigations are met; in some cases, missing subject-level data will be omitted from analyses because, for many physical health outcomes of interest, we will not have baseline data [71, 72]. The full information maximum likelihood (FIML)/imputation procedures will permit the inclusion of all participants for whom we have at least partially completed outcome assessments. If there is indication of non-ignorable missing data patterns, we plan to gauge the potential bias incurred thus and check the feasibility of statistical approaches (selection models, pattern-mixture models) that can mitigate the bias. All intervention sessions will have already taken place; thus, no procedures are necessary in this present follow-up study to ensure intervention protocol adherence. Those administering measures will be carefully trained and supervised to ensure measurement protocol adherence (see {18a} above). The authors plan to grant full public access to study protocol materials and to statistical code for main analyses, as well as access upon request to de-identified participant data. The Shamiri Institute headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya will act as the coordinating center. The headquarters are in a secure, locked building with secure, locked rooms inside of which the study team may safely store data. The AMHRTF headquarters, also a secure building with secure data storage locations, in Nairobi, Kenya, will serve as another study center. The trial steering committee consists of the study PIs (KVC, a doctoral student in clinical psychology and co-founder and scientific director of Shamiri Institute and TO, co-founder and CEO of Shamiri Institute), a number of professors of psychology and psychiatry (JW, EP, DN), a professor of statistics (TR), and the master-level research manager of Shamiri Institute (NJ). Members of the trial steering committee meet approximately weekly to plan and manage the trial and discuss issues as they arise; they also exchange frequent emails. The trial steering committee will plan the trial protocol, oversee collection and entry of data, supervise study staff during protocol implementation, oversee participant recruitment, and review and address potential adverse events and cases of risk as they occur. An external, independent Data Safety and Monitoring Board will not be recruited for this trial for several reasons. First, many members of the study team (e.g., EP, JW, CW, DN, VM, CM) have doctoral degrees in clinical or counseling psychology or degrees in psychiatry, and most of these individuals have many years of experience working with Kenyan youths specifically. Relatedly, several on-the-ground supervisors and a primary care clinician on the study team have degrees and clinical experience in psychology or medicine and are qualified to address emergencies and study issues. Second, the intervention was already delivered to all participants, thus, no intervention will be trialed or delivered during this study, thus, there will be no need to stop delivery of the intervention or remove people from it. Therefore, data and participant safety will instead be monitored by the highly qualified team of scientists and practitioners on the study team. There are no interventions being delivered during this trial, so there will be no collection necessary of intervention-related adverse events. In order to abide by local customs and preferences of guardians, participants who are minors or in schools will not be asked directly about suicidality, IPV, HIV risk, or pregnancy and children unless a school explicitly approves these questions for their students; participants who are adults and no longer in high school will be asked about these topics directly. If, during the course of outcome collection, adult participants reveal risk of harm to self or others, current IPV victimization or perpetration, or other high-risk circumstances or behaviors, they will receive risk assessment and management per the emergency protocol (see supplementary materials) and will be referred to appropriate resources identified by local experts on the study team. If minors incidentally (i.e., without being prompted) reveal or say something that suggests potential risk of harm to self or others, current substance abuse, current IPV victimization or perpetration, or other high-risk circumstances or behaviors, they too will receive risk assessment and management. Per the emergency protocol and as outlined in previous literature [73], this risk assessment and management will involve consultation with members of the study team who are professional practitioners with experience working in Kenya (see supplementary materials); however, for adolescents, coordination of referrals must be mediated by guardians (e.g., school officials or parents), instead of provided directly to participants. Additionally, cases identified as high risk on which IRB consultation is necessary and any adverse events occurring during the study implementation will be reported to the IRB of record. This trial does not involve intervention delivery, and the study procedures are highly unlikely to result in adverse events; thus, the trial will be monitored only by the study team, by the IRB of record (Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee), and by the trial sponsor, the Templeton World Charity Foundation, all of which will require frequent updates on trial proceedings. If any of these parties have concerns about trial conduct, the study team may ask an independent auditor to help identify and resolve these concerns. Protocol amendments will be communicated first to the study team through email or routine meetings. Then, as the investigators judge it necessary, these amendments will be communicated to the relevant parties such as the IRB of record (Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee), the trial sponsor, and the public via the study’s Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry (PACTR) registration page. Additionally, if the IRB and study team deem it appropriate, the participants may be notified of protocol changes via phone, email, and/or school announcements. Findings of this study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journal articles, conference presentations, and sharing of code, protocols, and potentially manuscripts and data on open-access platforms such as Open Science Foundation (OSF). The authors also plan to share findings in popular media outlets when possible (e.g., through blogs, podcasts, and online articles). The authors aim to make all published materials open access. Reporting of trial results will occur across several articles because of the many outcomes of interest in this study and the secondary and exploratory analyses that may be completed with the data collected.Methods in analysis to handle protocol non-adherence and any statistical methods to handle missing data {20c}

Plans to give access to the full protocol, participant level-data, and statistical code {31c}

Oversight and monitoring

Composition of the coordinating center and trial steering committee {5d}

Composition of the data monitoring committee, its role and reporting structure {21a}

Adverse event reporting and harms {22}

Frequency and plans for auditing trial conduct {23}

Plans for communicating important protocol amendments to relevant parties (e.g., trial participants, ethical committees) {25}

Dissemination plans {31a}

Discussion

This article includes a thorough description of the design of an RCT evaluating the long-term health effects of a brief, positively focused school-based mental health intervention delivered by peer lay-providers. Through this study, we will assess whether this intervention produces a long-term effect, over and above that of an active control group, on depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, perception of social support, and academic performance. We will also assess the effects of this intervention on a wide range of secondary health and behavioral outcomes, such as activity and heart rate variability, overall physical health, and substance use. This will be the first study to test the effects of character strength interventions on such a rich range of health outcomes over such an extended period.

Previous studies of the Shamiri intervention have shown promise for improvement of adolescent depression and anxiety [15, 20], and now, we would like to investigate if these effects hold over the long-term. The knowledge garnered from this trial (i.e., which health and behavioral outcomes are influenced by Shamiri) will directly inform efforts to disseminate this and other simple, low-cost, and stigma-free mental health interventions in low-resource settings.

The results from this study will add to the evidence base for character strength interventions. If we find that the Shamiri intervention impacts some of these health, academic and wellbeing outcomes in the long-term (3–4 years later), that may indicate that character strength interventions could provide a low-cost, stigma-free, and scalable solution to improve long-term health and behavioral outcomes of youth and adults in low-resource settings. This evidence may be of interest to policy makers, adolescent mental health practitioners, educators, and non-governmental organizations aiming to provide effective, scalable, and culturally appropriate care for young people in low-resource settings.

The trial’s results are subject to consideration of some scientific and practical limitations. First, the naturalistic setting of the schools which many of our participants attend leave us with less control over the study setting. As a result, there may be certain threats to internal validity. For instance, the time point of measure is likely to differ between the three RCT cohorts we will contact for follow-up. For reasons out of our control, such as the Kenyan general election cycle and KCSE examination period at schools, we will take follow-up measures between 3- and 4-years post-intervention. It is our position that threats such as these are counterbalanced by external validity provided by our naturalistic setting [74]. Second, contacting participants 3–4 years later may result in a biased sample of participants, as we may be more able to re-contact certain participants for follow-up. For instance, those participants that are still in school may be easier to reach through the school than those that have already graduated. Finally, certain health and behavioral measures, such as HIV status and pregnancy, are not considered appropriate for youths who are still in school, and this will limit our sample size for these analyses. Our study team has conducted three RCTs in a similar setting in Kenya and will apply best practices learned from our previous work [75].

Future research will be needed to identify additional low-cost, scalable, and stigma-free solutions to target mental disorders among youth in low-resource settings. For example, future research could collect long-term follow-up measures of participants in Shamiri digital, a single-session remote intervention which showed promising reductions in depressive symptoms over the long-term [69]. This study could also compare the long-term effects of Shamiri digital to digital cognitive behavioral therapy [76].

Our multicultural and multidisciplinary team is aware that a multitude of efforts will be needed to address global mental health challenges. We hope that this trial will provide a well-powered test of the effects of brief, lay-provider-delivered, positively focused interventions on a variety of health and wellbeing outcomes, thus informing research, policy, and practice in Kenya and potentially beyond.

Trial status

Protocol version 1.0 (January 12, 2022)

Recruitment has not yet started, and we anticipate completion of recruitment on approximately October 26, 2024.

Availability of data and materials {29}

A de-identified dataset used for the analyses of the effects of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes will be made publicly available upon request from the authors once the trial is concluded and all data has been analyzed as planned by the authors. This dataset will remain available at least three years following the conclusion of the study.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- LMICs:

-

Low-and middle-income countries

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- AMHRTF:

-

African Mental Health Research and Training Foundation

- GAD:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener

- PHQ-8:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- KCSE:

-

Kenyan Certificate of Secondary Education

- MSPSS:

-

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- SWEMBS:

-

Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale

- WEMBS:

-

Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale

- EPOCH:

-

Engagement, Perseverance, Optimism, Connectedness, Happiness Measure of Adolescent Wellbeing

- PILS:

-

Purpose in Life Scale

- GQ-6:

-

Gratitude Questionnaire-6

- PCSC:

-

Perceived Control Scale for Children

- SCSC:

-

Secondary Control Scale for Children

- ASWS:

-

Adolescent Sleep-Wake Scale

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- ASSIST:

-

Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

- VAWI:

-

Violence Against Women Instrument

- HRV:

-

Heart rate variability

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- KES:

-

Kenyan Shillings

- KoBo:

-

KoBo Toolbox

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criterion

- MAR:

-

Missing at random

- FIML:

-

Full information maximum likelihood

- PACTR:

-

Pan-African Clinical Trial Registry

- OSF:

-

Open Science Foundation

References

Promoting mental health. Concepts, emerging evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Otto C, Adedeji A, Devine J, Erhart M, et al. Mental health and quality of life in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic—results of the Copsy study. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2020;117(48):828–9. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0828.

Global Health Data Exchange. GBD Results tool. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2019. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool [updated 2021; cited 28 Dec 2021]

Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369(9569):1302–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7.

Degenhardt L, Saha S, Lim CCW, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, et al. The associations between psychotic experiences, and substance use and substance use disorders: findings from the World Health Organisation World Mental Health Surveys. Addiction. 2018;113(5):924–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14145 Abingdon Engl.

Bertha EA, Balázs J. Subthreshold depression in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22(10):589–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-013-0411-0.

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2.

Ndetei DM, Mutiso VN, Weisz JR, Okoth CA, Musyimi C, Muia EN, et al. Socio-demographic, economic and mental health problems were risk factors for suicidal ideation among Kenyan students aged 15 plus. J Affect Disord. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.055.

Global Health Observatory data repository | Human resources - Data by country. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHHR?lang=en [updated 2019; cited 24 Dec 2021]

Ndetei DM, Mutiso V, Maraj A, Anderson KK, Musyimi C, McKenzie K. Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among primary school children in Kenya. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(1):73–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1090-6.

Osborn TL, Wasil AR, Weisz JR, Kleinman A, Ndetei DM. Where is the global in global mental health? A call for inclusive multicultural collaboration. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(6):e100351. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100351.

Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Little treatments, promising effects? Meta-analysis of single-session interventions for youth psychiatric problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(2):107–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.007.

Niemiec RM. Character strenghts interventions: a field guide for practitioners: Hogrefe Publishing; 2017.

Walton GM. The new science of wise psychological interventions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(1):73–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413512856.

Osborn TL, Wasil AR, Venturo-Conerly KE, Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Group intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: outcomes of a randomized trial with adolescents in Kenya. Behav Ther. 2020;51(4):601–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.09.005.

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasil AR, Rodriguez M, Roe E, Alemu R, et al. The Shamiri group intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of a lay-provider-delivered, school-based intervention in Kenya. Trials. 2020;21(1):938. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04732-1.

Schleider JL, Weisz JR. A single-session growth mindset intervention for adolescent anxiety and depression: 9-month outcomes of a randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2018;59(2):160–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12811.

Emmons RA, Stern R. Gratitude as a psychotherapeutic intervention. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(8):846–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22020.

Cohen GL, Garcia J, Purdie-Vaughns V, Apfel N, Brzustoski P. Recursive processes in self-affirmation: intervening to close the minority achievement gap. Science. 2009;324(5925):400–3. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170769.

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Arango GS, Roe E, Rodriguez M, Alemu RG, et al. Effect of Shamiri layperson-provided intervention vs study skills control intervention for depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents in Kenya: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(8):829–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1129.

Venturo-Conerly K, Osborn TL, Wasil AR, Le H, Corrigan E, Wasanga C, et al. Testing the effects of the Shamiri intervention and its components on anxiety, depression, wellbeing, and academic functioning in kenyan adolescents: study protocol for a five-arm randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):829. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05736-1.

Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Ng MY, Eckshtain D, Ugueto AM, Vaughn-Coaxum R, et al. What five decades of research tells us about the effects of youth psychological therapy: a multilevel meta-analysis and implications for science and practice. Am Psychol. 2017;72(2):79–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040360.

Catherine WW. Performance determinants of Kenya certificate of secondary education (KCSE) in mathematics of secondary schools in Nyamaiya division, Kenya. Asian Soc Sci. 2011;7(2):107.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32(9):509–15. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06.

Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114(1–3):163–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026.

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasil AR, Schleider JL, Weisz JR. Depression and anxiety symptoms, social support, and demographic factors among Kenyan high school students. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(5):1432–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01646-8.

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly K, Gan J, Rodriguez M, Alemu R, Roe E, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms in Kenyan adolescents: prevalence, psychosocial correlates and sociodemographic factors in a nationally representative sample: PsyAr**v; 2020. https://psyarxiv.com/ze8tf/download

Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Gan J, Rodriguez M, Alemu RG, Roe E, et al. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms Amongst Kenyan Adolescents: Psychometric Properties, Prevalence, Sociodemographic Factors, and Psychological Wellbeing. PsyAr**v. 2021. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ze8tf.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Ng Fat L, Scholes S, Boniface S, Mindell J, Stewart-Brown S. Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): findings from the Health Survey for England. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(5):1129–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8.

Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R, Platt S, Joseph S, Weich S, et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-63.

Koushede V, Lasgaard M, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Nielsen L, Rayce SB, et al. Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan;1(271):502–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.003.

Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chong SA, Sambasivam R, Seow E, Jeyagurunathan A, et al. Psychometric properties of the short Warwick Edinburgh mental well-being scale (SWEMWBS) in service users with schizophrenia, depression and anxiety spectrum disorders. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0728-3.

Shah N, Cader M, Andrews WP, Wijesekera D, Stewart-Brown SL. Responsiveness of the Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS): evaluation a clinical sample. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):239. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-1060-2.

Wu Q, Ge T, Emond A, Foster K, Gatt JM, Hadfield K, et al. Acculturation, resilience, and the mental health of migrant youth: a cross-country comparative study. Public Health. 2018;162:63–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.006.

Kern ML, Benson L, Steinberg EA, Steinberg L. The EPOCH measure of adolescent well-being. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(5):586–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000201.

Crea G. The psychometric properties of the Italian translation of the Purpose in Life Scale (PILS) in Italy among a sample of Italian adults. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2016;19(8):858–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1277988.

Froh JJ, Sefick WJ, Emmons RA. Counting blessings in early adolescents: an experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. J Sch Psychol. 2008;46(2):213–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005.

Froh JJ, Fan J, Emmons RA, Bono G, Huebner ES, Watkins P. Measuring gratitude in youth: assessing the psychometric properties of adult gratitude scales in children and adolescents. Psychol Assess. 2011;23(2):311–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021590.

Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, McCarty CA. Control-related beliefs and depressive symptoms in clinic-referred children and adolscents: Developmental differences and model specificity. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.97.

Weisz JR, Francis SE, Bearman SK. Assessing secondary control and its association with youth depression symptoms. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(7):883–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9440-z.

Huber NL, Nicoletta A, Ellis JM, Everhart DE. Validating the adolescent sleep wake scale for use with young adults. Sleep Med. 2020;(69):217–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2020.01.021.

Zhang J, Paksarian D, Lamers F, Hickie IB, He J, Merikangas KR. Sleep patterns and mental health correlates in US adolescents. J Pediatr. 2017;182:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.007.

LeBourgeois MK, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Wolfson AR, Harsh J. The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(Supplement_1):257–65. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0815H.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addict Abingdon Engl. 1993;88(6):791–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x.

Nadkarni A, Garber A, Costa S, Wood S, Kumar S, MacKinnon N, et al. Auditing the AUDIT: a systematic review of cut-off scores for the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) in low- and middle-income countries. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;(202):123–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.04.031.

Ndetei DM, Khasakhala LI, Ongecha-Owuor FA, Kuria MW, Mutiso V, Kokonya DA. Prevalence of substance abuse among patients in general medical facilities in Kenya. Subst Abus. 2009;30(2):182–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897070902802125.

Gryczynski J, Kelly SM, Mitchell SG, Kirk A, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Validation and performance of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) among adolescent primary care patients. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2015;110(2):240–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12767.

McMaster L, Connolly J, Pepler D, Craig W. Peer to peer sexual harassment in early adolescence: a developmental perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2002;(14):91–105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230085.

Kidman R, Kohler H-P. Emerging partner violence among young adolescents in a low-income country: perpetration, victimization and adversity. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230085.

Nybergh L. Exploring intimate partner violence among adult women and men in Sweden [dissertation on the internet]. Sweden: University of Gothenburg; 2014. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/2077/35956 [cited 21 Jan 2022]

Mulawa M, Kajula LJ, Yamanis TJ, Balvanz P, Kilonzo MN, Maman S. Perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence among young men and women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Interpers Violence. 2018;33(16):2486–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515625910.

Orindi BO, Maina BW, Muuo SW, Birdthistle I, Carter DJ, Floyd S, et al. Experiences of violence among adolescent girls and young women in Nairobi’s informal settlements prior to scale-up of the DREAMS Partnership: Prevalence, severity, and predictors. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231737.

Puffer ES, Meade CS, Drabkin AS, Broverman SA, Ogwang-Odhiambo RA, Sikkema KJ. Individual- and family-level psychosocial correlates of HIV risk behavior among youth in rural Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(6):1264–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9823-8.

Shiferaw Y, Alemu A, Assefa A, Tesfaye B, Gibermedhin E, Amare M. Perception of risk of HIV and sexual risk behaviors among University students: implication for planning interventions. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:162. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-162.

Kim C, Woo J. Comparison of smart watch based pulse rate variability with heart rate variability. J Biomed Eng Res. 2018;39(2):87–93. https://doi.org/10.9718/JBER.2018.39.2.87.

Kim H-G, Cheon E-J, Bai D-S, Lee YH, Koo B-H. Stress and heart rate variability: a meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investig. 2018;15(3):235–45. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2017.08.17.

Goroso DG, Watanabe WT, Napoleone F, da Silva DP, Salinet JL, da Silva RR, et al. Remote monitoring of heart rate variability for obese children. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2021;66:102453. https://doi.org/10.3390/e23050540.

Moshe I, Terhorst Y, Opoku Asare K, Sander LB, Ferreira D, Baumeister H, et al. Predicting symptoms of depression and anxiety using smartphone and wearable data. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:625247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.625247.

Umair M, Chalabianloo N, Sas C, Ersoy C. HRV and stress: a mixed-methods approach for comparison of wearable heart rate sensors for biofeedback. IEEE Access. 2021;9:14005–24. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3052131.

Gradl S, Wirth M, Richer R, Rohleder N, Eskofier BM. An overview of the feasibility of permanent, real-time, unobtrusive stress measurement with current wearables. In: Proceedings of the 13th EAI International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 360–5. https://doi.org/10.1145/3329189.3329233.

Lee Y, Lee K-S. Associations between history of hospitalization for violence victimization and substance-use patterns among adolescents: a 2017 Korean National Representative Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15071543.

Kantor BN, Kantor J. Mental health outcomes and associations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional population-based study in the United States. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569083. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569083.

Karatas M, Saylan S, Kostakoglu U, Yilmaz G. An assessment of ventilator-associated pneumonias and risk factors identified in the intensive care unit. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32(4):817–22. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.324.10381.

Spybrook J, Bloom H, Congdon R, Hill C, Martinez A, Raudenbush S, et al. Optimal design plus empirical evidence: documentation for the “Optimal Design” software. William T Grant Found. 2011;5:2012.

Phang P, Vinck P. KoBo Toolbox. Harvard Humanitarian Initiative; 2005. Available from: https://www.kobotoolbox.org/kobo/

Osborn TL, Rodriguez M, Wasil AR, Venturo-Conerly KE, Gan J, Alemu RG, et al. Single-session digital intervention for adolescent depression, anxiety, and well-being: outcomes of a randomized controlled trial with Kenyan adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2020;88(7):657–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000505.

Venturo-Conerly KE, Osborn TL, Alemu R, Roe E, Rodriguez M, Gan J, et al. Single-session interventions for adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms in Kenya: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2022:104040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104040.

Van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data: CRC press; 2018.

Buuren van S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(1):1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasil AR, Osborn TL. Designing culturally and contextually sensitive protocols for suicide risk in global mental health: lessons from research with adolescents in Kenya. In Revisions.

Weisz JR, Ugueto AM, Cheron DM, Herren J. Evidence-based youth psychotherapy in the mental health ecosystem. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2013;42(2):274–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.764824.

Wasil A, Osborn TL, Venturo-Conerly KE, Wasanga CM, Weisz JR. Conducting global mental health research: lessons learned from Kenya. Glob Ment Health. 2021;8(8). https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2021.7.

Wasil AR, Osborn TL, Weisz JR, DeRubeis RJ. Online single-session interventions for Kenyan adolescents: study protocol for a comparative effectiveness randomised controlled trial. Gen Psychiatry. 2021;34(3):e100446. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100446.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Pascalyne Namai, Rosine Baseke, Brenda Ochuku, Okoth Paul Okoth, Kalori Wesonga, and Sunehra Arif for their assistance with coordinating this trial.

Funding

Primary funding for this trial was provided by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, grant # TWCF0633. These funds will provider for implementation costs of the study. Secondary funding was received from Alchemy Pay, a blockchain organization with the mission to bridge fiat and crypto currencies. Alchemy Pay is providing funding for the use of wearable fitness trackers to physically measure participant wellbeing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VC, TO, JW, EP, DN, CW, and TR devised the study concept and study design. NJ and KVC drafted the initial manuscript, and they along with TO, JW, EP, TR, VM, CM, and DN edited the manuscript. KVC, TO, JW, and CW developed intervention protocols. NJ will lead on the ground study implementation. All authors read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate {24}

This study was reviewed and approved by Kenyatta University’s Ethical Review Committee (PKU/2392/E1528). Informed consent/assent to participate will be obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Parents or legal guardians of child participants will also be contacted to provide consent according to local customs.

Consent for publication {32}

There are no details included here which identify participants. Model study consent and assent forms are available in supplementary materials.

Competing interests {28}

NJ, KVC, TO, and CW are affiliated with Shamiri Institute, a 501(c)3 non-profit which develops mental health interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. JW is affiliated as a science board member of Shamiri Institute. DN’s affiliated non-governmental organization, African Mental Health Research and Training Foundation, is a partner funded to implement this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Venturo-Conerly, K.E., Johnson, N.E., Osborn, T.L. et al. Long-term health outcomes of adolescent character strength interventions: 3- to 4-year outcomes of three randomized controlled trials of the Shamiri program. Trials 23, 443 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06394-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06394-7