Abstract

Background

The dropout rate is an important determinant of outcomes in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and should be carefully controlled. This study explored the current dropout rate in studies of Korean medicine (KM) interventions by systematic evaluation of RCTs conducted in the past 10 years.

Methods

Three clinical trial registries (Clinical Research Information Service, ClinicalTrials.gov, and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) were searched to identify RCT protocols for KM interventions, such as acupuncture, herbal medicine, moxibustion, or cup**, and studies of mixed interventions, registered in Korea from 2009 to 2019. The PubMed, Embase, and OASIS databases were searched for the full reports of these RCTs, including published journal articles and theses. Dropout rates and the reasons for drop** out were analyzed in each report. The risk of bias in each of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. The risk difference for drop** out between the treatment and control groups was calculated with the 95% confidence interval in a random effects model.

Results

Forty-nine published studies were included in the review. The median dropout rate was 10% in the treatment group (interquartile range 6.7%, 17.0%) and 14% in the control group (interquartile range 5.4%, 16.3%) and was highest in acupuncture studies (12%), followed by herbal medicine (10%), moxibustion (8%), and cup** (7%). Loss to follow-up was the most common reason for drop** out. The risk difference for drop** out between the intervention and control groups was estimated to be 0.01 (95% confidence interval − 0.02, 0.03) in KM intervention studies.

Conclusions

This review found no significant difference in the dropout rate between studies according to the type of KM intervention. We recommend allowance for a minimum dropout rate of 15% in future RCTs of KM interventions.

Review protocol registration

PROSPERO CRD42020141011

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dropout in the context of a clinical trial refers to a state in which observation is suspended or lost because a study participant cannot or does not attend the scheduled visits required by the research plan [1]. In most clinical trials, data are collected longitudinally. When data are collected repeatedly over a period of time, a proportion of the data will be lost if participants drop out of the study [2]. Drop** out is more common in subjects receiving interventions with potentially negative effects and might lead to incorrect estimation of the true effects of an intervention [3]. Loss of study data due to dropouts potentially introduces a risk of bias, so reducing the dropout rate is essential for a successful clinical trial. Furthermore, it is important to calculate an adequate sample size when designing a clinical trial in terms of research ethics while maintaining power and minimizing the exposure of patients to unnecessary risk [4, 5]. In terms of the quality, duration, and financial and ethical aspects of a clinical trial, understanding the relevant features of dropout is essential in the planning stages [6].

According to the Yearbook of Traditional Korean Medicine, updated in 2019, clinical research in the field of Korean medicine (KM) has been steadily increasing in the past two decades [7, 8]. Considering this growth, it is timely to consider improving the quality of clinical trials. In this context, it is important to understand the potential for dropouts and to be able to prepare a good management plan in future clinical studies of KM interventions. Previous analyses of factors related to dropouts in Korean clinical trials [6, 9] have only included data from institutional review board reports involving limited numbers of institutions and clinical trials. These studies were unable to provide general information on key dropout-related factors, estimates of overall dropout rates, or differences in dropout rates between various KM interventions.

The aims of this systematic literature review and meta-analysis were to identify factors affecting the likelihood of dropout in RCTs of KM interventions over a 10-year period and to estimate the potential dropout rate in such studies. It is hoped that this information could be used when planning future clinical research in the field of KM.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of studies

Given that the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) was established in Korea in 2010, the plan was to include all RCTs of KM interventions that were conducted in Korea from 2009 to March 2019. No restrictions on the blinding methodology used were imposed at the time of selection. Non-randomized clinical trials, clinical trial protocols, and as yet unpublished studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Subjects who had been randomly assigned to a KM intervention in a clinical study conducted in Korea and then deviated from the study time points before the end of treatment or evaluation after screening were included. No specific restrictions were placed in terms of the type of disease for which patients were receiving KM or their symptoms.

Types of intervention

The KM interventions used in the RCTs included acupuncture, moxibustion, cup** and embedding of catgut, and administration of extracts, herbal medicine, chuna, electroacupuncture, pharmaco-acupuncture, and bee venom. No specific restrictions were imposed regarding the use of each intervention, number of treatments, or treatment methods. If a KM intervention was used in combination with conventional therapy, it was classified as a mixed intervention. Studies that included three or more interventions were excluded.

Comparison of interventions

Any type of comparative intervention was included with no specific limitations.

Outcome measures

There were no specific restrictions on the types of outcome variables used in individual studies or on the timing of evaluation.

Search strategy

The literature search was performed in two stages. In the first stage, all RCTs planned in Korea as of March 2019 were identified using the CRIS, ClinicalTrials.gov, and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) clinical trial registries. These RCTs had to be identified one by one because there is no established method for searching for KM interventions in these registries under the tag of country or RCT for each type of KM intervention (acupuncture, moxibustion, cup**, embedding of catgut, administration of extracts, herbal medicine, chuna, electro-acupuncture, pharmaco-acupuncture, or bee venom therapy). The search strategy used is outlined in Supplementary File 1. In the second stage, each study identified by the initial screening was searched for in the PubMed, Ovid Embase, and Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System (OASIS) databases by title, author, and research registration number to check if it was published. No language restrictions were imposed. Relevant dissertations and articles published in journals from 2009 to March 2019 were included.

Study selection

One researcher (SRJ) conducted the literature search, and two researchers (THK and DWN) assessed the eligibility of the studies identified for inclusion in the analysis. The individual research results corresponding to the list extracted from the clinical research registries and the original text of the published papers were checked.

Data extraction and management

Two researchers (SRJ and DWN) extracted data from the included studies, and any disagreement was resolved by discussion. The data extracted from these studies included the first author, year of publication, type of institution, number of participating institutions, blinding methodology, and number of subjects in the treatment group and control group, as well as the total number of subjects, study design, type of intervention used in the KM group and control group, diseases or conditions treated, total number of treatments, frequency of assessment, and source of research funding. The reason for dropout was classified as withdrawal of consent, occurrence of an adverse event or serious adverse event, loss to follow-up, intervention discontinued, violation of eligibility criteria, protocol deviation, or others. The total number of dropouts from the treatment group and from the control group in each study was extracted.

Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (SRJ and DWN) independently assessed the risk of bias in each study using the Cochrane Handbook criteria. In the event of disagreement between the reviewers, the final decision was made by a third reviewer (THK). The risks of bias were evaluated in seven domains, including sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of research personnel, blinding of study participants, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting of outcomes, and other biases. The results of this evaluation were graded as “high risk of bias,” “low risk of bias,” or “unclear risk of bias” [10, 11].

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

Primary analysis

The number and percentage of dropouts, reasons for dropout, and comparative dropout rates were analyzed according to the type of intervention in a narrative fashion. The proportion of overall dropouts to intervention-specific dropouts was calculated as the median and interquartile range (IQR) using the RStudio software (version 5.3.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

The risk difference (RD) was calculated to obtain a summary estimate of dropouts between the groups. The reason for using RD as a summary estimate was that the risk ratio or odds ratio was assumed to be unavailable because there could be a group without any dropouts in the included studies [11]. In this review, a random effects model was used for the meta-analysis because significant clinical heterogeneity between the individual studies had been expected due to considerable differences in the study design and performance. The meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager (version 5.3.5 for Windows; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014).

Subgroup analysis

A subgroup analysis was performed according to the intervention used (acupuncture, herbal medicine, moxibustion, cup**, and mixed). A sensitivity analysis was conducted according to whether the study was blinded or open and whether it was single-center or multicenter to identify the factors influencing the summary effect estimates.

Analysis of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was evaluated using the chi-square test and the I2 statistic. In the chi-square test, a significance level of 0.10 was used. For the evaluation of the I2 statistic, the following criteria were used: 0% ≤ I2 ≤ 40%, “heterogeneity may not be important”; 30% ≤ I2 ≤ 60%, “may have moderate heterogeneity”; 50% ≤ I2 ≤ 90%, “may be actual heterogeneity”; and 75% ≤ I2 ≤ 100%, “significant heterogeneity” [10, 11].

Publication bias

We planned to assess a funnel plot visually to determine whether there was publication bias if more than 10 studies could be included in the meta-analysis [11].

Results

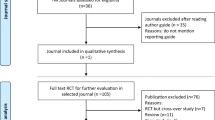

The search of the clinical trial registries initially yielded 174 studies of interest. After screening, 49 studies (2943 participants) were eligible for inclusion in this review (Fig. 1) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60]. The relevant details of these studies are summarized in Table 1.

Thirty-four of the 49 RCTs were performed at a single center [14, 15, 17, 19,20,21, 23,24,25,26,27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42,43,44,45, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53, 57,58,59,60], and 15 were multicenter [12, 13, 16, 18, 22, 28, 30, 33, 36, 38, 41, 46, 54,55,56]. Twenty RCTs were performed in a double-blind manner [20, 21, 25, 30, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, 52, 54,55,56, 58], and 14 were single-blind [12, 14, 15, 17,18,19, 23, 24, 27, 29, 45, 47, 51, 53]. Fifteen studies were performed without any blinding of participants or researchers [13, 16, 22, 26, 28, 31, 43, 44, 46, 48,49,50, 57, 59, 60]. Thirty-nine studies had a parallel design with a single control group [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, 25,26,27, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51, 53, 55, 56], six included three or more parallel intervention groups [23, 24, 42, 52, 54, 58], and two had a crossover design [57, 59]. Acupuncture was the most frequently investigated KM and was assessed in 21 studies (n = 195) [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Herbal medicines were investigated in 17 studies (n = 132) [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44, 54,55,56,57,58], moxibustion in four (n = 25) [45,46,47, 59], cup** therapies in two (n = 5) [48, 49], and mixed interventions in five (n = 12) [50,51,52,53, 60] (Supplementary File 2). Forty-four studies received funding support from the government, research institutions, or schools [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 58]. Only one study was not supported by any external funding [16]. Four studies did not provide any information on funding [33, 57, 59, 60] (Supplementary File 3).

The treatment duration in the studies ranged from 2 to 24 weeks. The median treatment duration was 4 weeks after the exclusion of four studies that did not mention the treatment duration [20, 27, 53, 57].

Seven of the 49 studies eligible for inclusion in the review were excluded from the meta-analysis because no dropouts could be confirmed (n = 3), the study included more than three groups (n = 2), or it had a crossover design (n = 2). Data for the remaining 42 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Risk of bias in the included studies

A majority of the included studies showed a low risk of bias in most domains. Sequence generation was conducted appropriately using a random number table or by coin tossing, and allocation concealment was achieved adequately in the studies using sealed opaque envelopes. However, in the open trials, the risk of bias was evaluated as high or unclear in the domains concerning blinding of research personnel and participants [12, 13, 16, 22, 26, 28, 29, 31, 43, 44, 46, 48,49,50, 57]. Selective outcome reporting and other domains showed a low risk of bias in most studies (Supplementary Files 4 and 5).

Analysis of dropouts

The total number of dropouts in all studies was 369, with the highest number in studies of acupuncture. There were 188 dropouts in the treatment groups, 80 (43%) of which were from studies of acupuncture, 74 (39%) were from herbal medicine studies, 25 (13%) were from studies of moxibustion, three (2%) were from cup** studies, and six (3%) were from mixed interventions. Of the 181 dropouts from the control groups, 102 (56%) were from acupuncture studies, 58 (32%) were from herbal medicine studies, 13 (7%) were from moxibustion studies, two (1%) were from cup** studies, and six (3%) were from mixed intervention studies.

The reported overall dropout rate was 10% (IQR 6.7%, 17.0%) in the treatment group, 12% (IQR 7.9%, 16.5%) in the control group, and 12% (IQR 7.9%, 16.5%) in all groups. When classified by type of intervention, the median dropout rate was 12% (IQR 10.8%, 21.3%) for acupuncture studies, 10% (IQR 7.2%, 14.0%) for herbal medicine studies, 8% (IQR 8.1%, 19.9%) for moxibustion studies, 7% (IQR 6.1%, 8.3%) for cup** studies, and 4% (IQR 2.5%, 7.1%) for mixed intervention studies (Table 2).

Loss to follow-up was the most common reason for dropouts overall. When examined by type of intervention, loss to follow-up was the most common reason for dropout in studies using acupuncture, herbal medicine, and cup** whereas withdrawal of consent was the most frequent reason in the moxibustion and other studies (Supplementary Files 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10).

Meta-analysis on the dropout rates

The RD in dropout rates between the intervention and control groups was estimated to be 0.01 (95% confidence interval [CI] − 0.02, 0.03) in the 42 studies regardless of the type of intervention, suggesting no significant difference in the dropout rate. Moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 39%) was observed in the meta-analysis of studies of different interventions. The RD was estimated to be less than 0.01 (95% CI − 0.05, 0.06) in the acupuncture studies, 0.01 (95% CI − 0.02, 0.04) in the herbal medicine studies, 0.17 (95% CI − 0.14, 0.49) in the moxibustion studies, less than 0.01 (95% CI − 0.11, 0.12) in the cup** studies, and less than 0.01 (95% CI − 0.10, 0.09) in the studies with mixed interventions (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis and publication bias

There was no significant difference in the RD for dropout according to whether the study design was blinded or open, whether it was single-center or multicenter, or whether or not the number of treatments administered was more than eight (the median number of visits in the included studies) (Table 3). Visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated no significant publication bias in the meta-analysis (Supplementary File 11).

Discussion

This systematic review investigated the status of dropouts from 49 RCTs of KM interventions between 2009 and 2019. The most common intervention was acupuncture (21 studies), followed by herbal medicine (17 studies), mixed interventions (five studies), moxibustion (four studies), and cup** (two studies). The estimated median dropout rate was 12% (IQR 7.9%, 16.5%) across the treatment and control groups. The most common reason for drop** out was loss to follow-up in the studies of acupuncture, herbal medicine, and cup** and withdrawal of consent in the moxibustion and other studies. A meta-analysis of all studies found no statistically significant RD in the dropout rate between the treatment and control groups; this finding remained the same when the data were analyzed by type of intervention, methodology (whether the study was blinded or not), and setting (single-center or multicenter).

The dropout rates identified in this review are slightly lower than those previously reported in the literature [8, 61, 62]. Moreover, the main reason cited for drop** out in a previous review was non-compliance with treatment [9], whereas we found loss to follow-up and withdrawal of consent to be the most common reasons. This inconsistency may reflect differences in the interventions used in the studies included in the different reviews. In a previous report, only studies using acupuncture were evaluated, whereas our review included various interventions.

This research has several strengths. First, it is the only systematic review and meta-analysis of dropouts from RCTs in the KM field. The reasons for drop** out were classified by the type of KM intervention, and the median dropout rates were estimated accordingly. A previous systematic review of studies that investigated structural outcomes in patients with rheumatic diseases found a dropout rate of more than 20%, which raises doubt regarding the validity of its findings [63]. Reasonable data for assuming a potential dropout rate are critical when calculating the sample size. Second, our systematic review included studies performed at different institutions in Korea; therefore, our findings could be generalized to all of Korea. It would be impossible to determine the overall status of dropouts from RCTs by simply analyzing research documents at specific institutions. However, this study differs from the previous studies in that the reasons for dropouts in the individual studies were classified and compared with the ratio of dropouts by interventions and the risk of dropouts between the treatment group and the control group through a systematic evaluation of previously published literature. Therefore, our present findings would be helpful when estimating the likely dropout rate for each type of KM intervention in future clinical studies.

There are also some limitations to this review. First, it analyzed secondary data extracted from previously published reports and did not include unpublished studies (i.e., gray literature). Second, many studies did not provide clear reasons for dropouts, which were categorized as unknown in this study. In these studies, the exact reason for the dropouts could not be confirmed, which precluded the drawing of a definite conclusion. Third, this research was preliminary in nature and the only such study ever conducted in Korea, so may not reflect the real-world situation in other countries, where the findings for other types of KM intervention may be different. Fourth, the analysis according to the type of intervention might have been affected by the number of included studies. For example, our finding that RCTs of acupuncture had the highest dropout rates may simply reflect the fact that our study included a large number of acupuncture studies. Moreover, there could have been factors or predictors related to the dropouts in the KM intervention trials that we could not identify. This possibility should be evaluated in the future.

Several findings of this research warrant further discussion. First, adverse events were not found to be a common reason for drop** out of the KM intervention trials. The dropout rate due to adverse events was found to be 5% in this study. Second, the type of intervention used in control subjects might not be an important determinant of the risk of drop** out. Non-compliance is widely thought to indicate dissatisfaction with treatment. However, in the studies that included a sham control group, the median dropout rate was estimated to be 11% (IQR 9.3%, 15.4%) across the treatment and control groups and was not significantly different from that in studies that used other types of control interventions (the estimated median dropout rate for all studies included in this review was 12% [IQR 7.9%, 16.5%]). When planning an RCT, investigators should consider specific design factors likely to affect the dropout rate, including frequency of visits, follow-up assessments, and type of intervention. The inclusion of a sham control group might not be an important factor in terms of an increased dropout rate. Finally, only 49 of the 174 potentially eligible KM studies entered into the clinical trial registries in the past 10 years have been published, suggesting a publication rate of about 28%. However, our search strategy may not have identified the exact number of relevant studies, which might have introduced a degree of bias. Nevertheless, it is clear that a substantial amount of research in the field of KM have not been formally published.

In this research, we examined methodological factors that might increase the dropout rate, such as blinding, whether or not the study was single-center or multicenter, and treatment frequency, but could not identify any such factors. It is uncertain whether this negative result reflects a lack of studies; moreover, it is unclear whether they are actually relevant. Dropout-related factors should be examined in a more extensive review that includes a larger number of clinical studies in the future or alternatively by surveys of actual dropouts in the clinical trials presently underway.

Conclusions

This review and meta-analysis of RCTs in which KM interventions were used revealed a dropout rate of less than 15% over a 10-year period and found no statistically significant difference in the dropout rate between the treatment and control groups. These data can be used to calculate the likely dropout rate when designing a clinical trial using KM. Further studies are needed to develop a strategy for reducing the factors affecting dropout rates.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials supporting the conclusions of this research are included in the article.

Abbreviations

- KM:

-

Korean medicine

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- CRIS:

-

Clinical Research Information Service

- WHO ICTRP:

-

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform

- ROB:

-

Risk of bias

- RD:

-

Risk difference

- OASIS:

-

Oriental Medicine Advanced Searching Integrated System

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- SAE:

-

Serious adverse event

References

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. Medical clinical trial analysis statistical guideline: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2016.

Lee KH. Sample size calculations with dropouts in clinical trials. Commun Korean Stat Soc. 2008;15(3):353–65.

Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, Montori V, Gøtzsche PC, Devereaux PJ, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869.

Collyar DE. The value of clinical trials from a patient perspective. Breast J. 2000;6(5):310–4.

Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research: CRC press; 1990.

Kim HJ. Analysis of predictors of drop-out on medical clinical trial. KR: Catholic University of Korea; 2009.

Ministry of Food and Drug Safety. National Institute of Food and Drug Safety Evaluation Herbal Medicinal Products Division Herbal Medicine Investigational New Drug Application status by year: Ministry of Food and Drug Safety; 2018.

Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine. Yearbook of traditional Korean medicine: Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine; 2019.

Kim AR, Lee MS, Hong JY. Factors related to dropout in clinical trials of acupuncture and moxibustion. J Korean Oriental Med. 2011;32(4):128–38.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; [updated March 2011]. Available form www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed Mar 2019.

Kim SY, Park JE, Seo HJ, Lee YJ, Jang BH, Son HJ, Suh HS, Shin CM. NECA’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews and meta-analyses for intervention: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency; 2011.

Choi SM. Effects of acupuncture on hot flashes in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women--a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Menopause (New York, NY). 2010;17(2):269–80.

Choi SM. Acupuncture for treating dry eye: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;88(8):e328–33.

Choi SM. Adjacent, distal, or combination of point-selective effects of acupuncture on temporomandibular joint disorders: a randomized, single-blind, assessor-blind controlled trial. Integr Med Res. 2012;1(1):36–40.

Choi SM. Acupuncture lowers blood pressure in mild hypertension patients: a randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded pilot trial. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23(5):658–65.

Choi SM. Acupuncture for chronic fatigue syndrome and idiopathic chronic fatigue: a multicenter, nonblinded, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:314.

Choi SM. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for functional constipation: a randomised, sham-controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):186.

Choi SM. Electroacupuncture for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a multicenter, randomized, assessor-blinded. Controlled Trial Diabetes Care. 2018;41(10):e141–e2.

Han CH. Efficacy and safety of thread embedding acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):680.

Jung WS. Intradermal acupuncture on shen-men and nei-kuan acupoints improves insomnia in stroke patients by reducing the sympathetic nervous activity: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Chinese Med. 2009;37(6):1013–21.

Kim KS. Efficacy of pharmacopuncture using root bark of Ulmus davidiana Planch in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Acupuncture Meridian Stud. 2010;3(1):16–23.

Kim SM. Effects of electroacupuncture on the muscle cramps of liver cirrhosis patients: a randomized controlled study. J Intern Korean Med. 2018;39(4):511–9.

Lee MS. Acupuncture for hot flushes in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a randomised, sham-controlled trial. Acupunct Med. 2011;29(4):249–56.

Lee JH. The effect of East-West Collaborative Medicine on Chronic Cervical Pain. Acupuncture. 2013. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01205958. Accessed Mar 2019.

Lee SH. Intradermal acupuncture along with analgesics for pain control in advanced cancer cases: a pilot, randomized, patient-assessor-blinded, controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(4):1137–43.

Nam HJ. A comparative study on the effects of systemic manual acupuncture, periauricular electroacupuncture, and digital electroacupuncture to treat tinnitus: a randomized, paralleled, open-labeled exploratory trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):85.

Park KM. Pain and sensory detection threshold response to acupuncture is modulated by co** strategy and acupuncture sensation. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2014;14:324.

Park JW. Individualized acupuncture for symptom relief in functional dyspepsia: a randomized controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med (New York, NY). 2016;22(12):997–1006.

Shin BC. Electroacupuncture as a complement to usual care for patients with non-acute pain after back surgery. 2018. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01966250. Accessed Mar 2019.

Song MY. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a multicenter, randomized, patient-assessor blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Spine. 2013;38(7):549–57.

Yang GY. Acupuncture for lumbar spinal stenosis. In: Yang GY, editor. 2013. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1136/acupmed-2015-010962: https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01987622. Accessed Mar 2019.

Yoo HS. Effect of acupuncture for radioactive-iodine-induced anorexia in thyroid cancer patients: a randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14(3):221–30.

Chang GT. Effects of Astragalus extract mixture HT042 on height growth in children with mild short stature: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Phytother Res. 2018;32(1):49–57.

Jung IC. The effect of Bunsimgi-eum on Hwa-byung: randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144(2):402–7.

Kim HJ. Efficacy and adverse events of Bangpungtongseong-san (Bofutsusho-san) and Bangkihwangki-tang (Boiogiot-tang) by oriental obesity pattern identification on obese subjects: randomized, double blind. Placebo-controlled Trial. J Oriental Rehab Med. 2011;21(2):265–78.

Kim JS. The effects of Banha-sasim-tang on dyspeptic symptoms and gastric motility in cases of functional dyspepsia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, and two-center trial. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:265035.

Kim HJ. The effects of co-administration of probiotics with herbal medicine on obesity, metabolic endotoxemia and dysbiosis: a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(6):973–81.

Kim JS. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a traditional herbal formula, Yukmijihwang-tang in elderly subjects with xerostomia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2016;182:160–9.

Kim HJ. Efficacy and safety of Codonopsis lanceolata (S. et Z.) Trautv. Extract on the improvement of the hypersensitivity reaction in allergic rhinitis patients. Kor. J. Herbology. 2019;34(1):13–21.

Ko SG. Corrigendum to “Efficacy and safety of Sipjeondaebo-tang for anorexia in patients with cancer: a pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial”. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;2018:6162106.

Nah SS. The clinical efficacy and safety of Gumiganghwal-tang in knee osteoarthritis: a phase II randomized double blind placebo controlled study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;2018:3165125.

Son CG. Antifatigue effects of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. PloS one. 2013;8(4):e61271.

Yoon SW. Bojungikki-tang for cancer-related fatigue: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9(4):331–8.

Yoon SW. Efficacy and safety of the traditional herbal medicine, Gamiguibi-tang, in patients with cancer-related sleep disturbance: a prospective, randomized, wait-list-controlled, pilot study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2018;17(2):524–30.

Choi SM. The effectiveness of moxibustion for the treatment of functional constipation: a randomized, sham-controlled, patient blinded, pilot clinical trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:124.

Choi SM. Moxibustion treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a multi-centre, non-blinded, randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness and safety of the moxibustion treatment versus usual care in knee osteoarthritis patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101973.

Yoo HS. A feasibility study of moxibustion for treating anorexia and improving quality of life in patients with metastatic cancer: a randomized sham-controlled trial. Integr Cancer Ther. 2017;16(1):118–25.

Choi BI. The effectiveness of wet cup** on persistent non-specific low back pain. 2011. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00925951. Accessed Mar 2019.

Hong KE. Cup** for treating neck pain in video display terminal (VDT) users: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Occup Health. 2012;54(6):416–26.

Kim JW. Anxiety and anger symptoms in Hwabyung patients improved more following 4 weeks of the emotional freedom technique program compared to the progressive muscle relaxation program: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015.

Kim JS. The effect of clove-based herbal mouthwash on radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer: a single-blind randomized preliminary study. OncoTargets Ther. 2016;9:4533–8.

Park SU. Efficacy of combined treatment with acupuncture and bee venom acupuncture as an adjunctive treatment for Parkinson’s disease. J Altern Complement Med. 2018;24(1):25–32.

Yoon SW. The efficacy and safety of Jaungo, a traditional medicinal ointment, in preventing radiation dermatitis in patients with breast cancer: a prospective, single-blinded, randomized pilot study. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;2016:9481413.

Jung IC. The comparative clinical study of efficacy of Gamisoyo-San (Jiaweixiaoyaosan) on generalized anxiety disorder according to differently manufactured preparations: multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;158 Pt A:11–7.

Kim JS. An herbal medicine, Yukgunja-tang is more effective in a type of functional dyspepsia categorized by facial shape diagnosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;2018:8546357.

Kim JW. Effects of a herbal medicine, Yukgunja-tang extract granule, on functional dyspepsia patients by Sasang constitution: placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. J Sasang Constitutional Med. 2018;30(2):42–54.

Kwon YD. Safety of Ojeok-san extract powder and soft extract in healthy male volunteers, single center, randomized controlled, cross-over study. J Korean Med Rehabil. 2019;29(1):63–73.

Park JW. Effect of korean herbal medicine combined with a probiotic mixture on diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2013;2013:824605.

Kwon JN. The effect and safety of moxibustion therapy for overactive bladder patients. 2018. https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02271607. Accessed Mar 2019.

Kim YB. Anti-inflammatory effect of Keigai-rengyo-to extract and acupuncture in male patients with acne vulgaris: a randomized controlled pilot trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(5):501–8.

Oostenbrink JB, Al MJ, Rutten-van Mölken MP. Methods to analyse cost data of patients who withdraw in a clinical trial setting. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21(15):1103–12.

Yin C, Seo B, Park H-J, Cho M, Jung W, Choue R, et al. Acupuncture, a promising adjunctive therapy for essential hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Neurol Res. 2007;29(sup1):98–103.

Baron G, et al. Violation of the intent-to-treat principle and rate of missing data in superiority trials assessing structural outcomes in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheumatism. 2005;52(6):1858–65 2018;10(6):591-613.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the Traditional Korean Medicine R & D Program funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) (HB16C0048-010016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SRJ, THK, and DWN developed the study concept and design, performed the data acquisition and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

: Search strategy used for the Clinical Research Information Service, ClinicalTrials.gov, and World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform registries.

Additional file 2.

: Number of included studies listed by type of intervention.

Additional file 3.

: Summary of the included randomized controlled trials.

Additional file 4.

: Risk of bias assessment.

Additional file 5.

: Risk of bias assessment summary for the individual studies.

Additional file 6.

: Reasons for drop** out in the 21 studies of acupuncture.

Additional file 7.

: Reasons for drop** out in the 12 studies of herbal medicine.

Additional file 8.

: Reasons for drop** out in the three studies of moxibustion.

Additional file 9.

: Reasons for drop** out in the two studies of cup**.

Additional file 10.

: Reasons for drop** out in the four studies of mixed interventions.

Additional file 11.

: Funnel plot assessing publication bias.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, Sr., Nam, D. & Kim, TH. Dropouts in randomized clinical trials of Korean medicine interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trials 22, 176 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05114-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05114-x