Abstract

Infection (either community acquired or nosocomial) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in critical care medicine. Sepsis is present in up to 30% of all ICU patients. A large fraction of sepsis cases is driven by severe community acquired pneumonia (sCAP), which incidence has dramatically increased during COVID-19 pandemics. A frequent complication of ICU patients is ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP), which affects 10–25% of all ventilated patients, and bloodstream infections (BSIs), affecting about 10% of patients. Management of these severe infections poses several challenges, including early diagnosis, severity stratification, prognosis assessment or treatment guidance. Digital PCR (dPCR) is a next-generation PCR method that offers a number of technical advantages to face these challenges: it is less affected than real time PCR by the presence of PCR inhibitors leading to higher sensitivity. In addition, dPCR offers high reproducibility, and provides absolute quantification without the need for a standard curve. In this article we reviewed the existing evidence on the applications of dPCR to the management of infection in critical care medicine. We included thirty-two articles involving critically ill patients. Twenty-three articles focused on the amplification of microbial genes: (1) four articles approached bacterial identification in blood or plasma; (2) one article used dPCR for fungal identification in blood; (3) another article focused on bacterial and fungal identification in other clinical samples; (4) three articles used dPCR for viral identification; (5) twelve articles quantified microbial burden by dPCR to assess severity, prognosis and treatment guidance; (6) two articles used dPCR to determine microbial ecology in ICU patients. The remaining nine articles used dPCR to profile host responses to infection, two of them for severity stratification in sepsis, four focused to improve diagnosis of this disease, one for detecting sCAP, one for detecting VAP, and finally one aimed to predict progression of COVID-19. This review evidences the potential of dPCR as a useful tool that could contribute to improve the detection and clinical management of infection in critical care medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infection in critical care medicine

Infectious pathology represents a leading cause of admission to the intensive care units (ICU). Sepsis (defined by the presence of a dysregulated host response to infection inducing organ dysfunction) is present in up to 30% of all ICU patients, as recently reported by Sakr et al. in a large study with 10,000 patients from 730 ICUs [1]. One of the leading causes of sepsis is severe community acquired pneumonia (sCAP) of bacterial or viral origin [2]. Current Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemics has largely boosted the cases of sCAP all over the world.

In turn, infection is one of the most frequent complications in patients who are critically ill. Compromise of body’s physical barriers by invasive devices, surgical aggression or traumatic injury, disruption of the mucosa, pressure sores, ventilator-induced lung injury, immune suppression, poor nutritional state, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics which alter the commensal microbiota, combined with the increased exposition to opportunistic (often multi-drug resistant, MDR) pathogens [3], all represent predisposing factors favouring ICU acquired infections [4]. In fact, approximately 19.2% of ICU patients develop infections compared to approximately 5.2% of infections developed by patients staying in all other hospital wards [3, 5]. Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) affects 10–25% of all ventilated patients after at least 48 h on mechanical ventilation [6]. Other frequent nosocomial infections affecting critically ill patients are catheter-associated urinary tract infection, bloodstream infection (BSIs), skin and wound infections, sinusitis, and gastrointestinal infection (often with Clostridium difficile) [4]. Clinical management of these infectious diseases or complications of the critically ill patient faces several challenges, including early diagnosis with microorganism identification, severity stratification, prognosis assessment and treatment guidance. Digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) is a next-generation PCR method that represents an opportunity to address these challenges.

dPCR: technical principles and applications

dPCR has emerged as a promising technology that might fill in the current gaps of other standard or emerging diagnostic technologies employed in microbiology (Table S1 – additional file 1). dPCR is based on the division of the PCR mastermix (all components including DNA or RNA targets) into thousands of partitions. PCR amplification of target genes occurs in each individual partition, acting as an individual microreactor [7]. These partitions can be created using a number of different mechanisms, such as emulsified microdroplets suspended in oil (droplet digital PCR, ddPCR), manufactured microwells, or microfluidic valving [8]. The distribution of target sequences in the partitions is detected by fluorescence at endpoint. Quantification of target genes is estimated based on Poisson’s distribution, by calculating the ratio of positive partitions (presence of fluorescence) over the total number of partitions [9]. This technology has several advantages: i) it is less affected by PCR inhibitors than other standard or real-time PCR (qPCR) methods, as target sequences are concentrated in the microreactors; ii) it also offers a high reproducibility of the results; iii) it provides an absolute quantification of the target sequence without the need for standard curves; and iv) it has an improved analytical sensitivity ideal for detecting microbial genes, for species identification or for genes conferring antimicrobial resistance or higher pathogenicity. dPCR also presents some limitations: i) it is unable to distinguish between viable and non-viable microorganisms (an inconvenient which affects all PCR-based methods); ii) it might have different sensitivity for different types of microorganisms; iii) it needs specialized training; and iv) it has a high cost, particularly to acquire the devices. This represents a major drawback for applications in low or middle income countries, for example during the COVID-19 pandemics [7, 9]. In spite its limitations, the previously mentioned dPCR properties make it an ideal tool for clinical applications in the field of microbiology and infectious diseases [7]. In this article we reviewed the existing evidence on the use of dPCR to improve the clinical management of infection in critical care medicine.

Methods

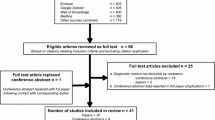

We searched PudMed combining the following MESH terms: “digital PCR”, “digital droplet PCR”, “droplet digital PCR” and “droplet PCR” with “ICU”, “critical AND infection”, “critically ill AND infection”, “severe infection”, “critical care”, “pneumoniae”, “ventilator-associated pneumoniae”, “ventilator”, “ventilation”, “sepsis”, “septic shock”, “bloodstream infections”, “skin and soft tissue infections”, “necrotizing fasciitis”, “peritonitis”, “invasive pulmonary aspergillosis”. We found a total of 487 PubMed articles. Only articles in English were considered. Using PMID we excluded duplicated articles appearing in more than one search, obtaining a total of 198 articles. We screened these articles for relevance and excluded 166 for the reasons mentioned in Fig. 1. Finally, thirty-two articles were included in this review (Table 1). These articles were further divided in two groups, one focused on the pathogens—diagnosis of infection, prognosis and treatment guidance (n = 23)—and the other focused on the host response to infection (n = 9).

Evidence on the use of dPCR for the diagnosis and management of infection in critical care medicine (Fig. 2)

Applications of dPCR targeting microbial genes

The gold standard for the detection of bacterial and fungal pathogens still relies on culture based methods that present a long turnaround time, and often yield low positivity rates [10]. For viral pathogens the reference method is frequently qPCR [11,12,13]. As previously stated, dPCR presents several advantages making it an ideal technique for the detection and quantification of microbial genes (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Bacterial identification in blood or plasma

dPCR has been used in critical care medicine for the detection of different bacterial pathogens in septic patients or patients with a suspected BSI [10, 14,15,16]. Yamamoto et al. successfully diagnosed a septic patient with a Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) disseminated infection by detecting MTB complex-specific sequences in total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) in plasma. dPCR was employed after sputum, urine, and blood samples all tested negative by COBAS TaqMan MTB and MAI tests (Roche Diagnostics) and TSPOT.TB test (Oxford Immunotec) and mycobacterial culture [14]. These results indicate that dPCR is more sensitive than the other molecular and culture methods, and that dPCR could serve as a less invasive diagnostic tool for MTB infections [14]. In two other studies [15, 16] dPCR was used to detect major BSI Gram-negative pathogens in cfDNA isolated from plasma of critically ill patients. Shin et al. [15] developed a dPCR assay able to detect four major Gram-Negative pathogens and four common antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes. Zheng et al. [16] work focused on only two of the most common MDR Gram-Negative pathogens. These assays report a time from sample collection to result of three to four hours and a detection limit of one Colony-forming Unit/ml of bacteria in the blood [15, 16]. The study by Shin et al. indicated that dPCR was also more sensible than qPCR [15]. Hu et al. [10] compared the detection of pathogens and AMR genes by dPCR with metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing (mNGS) and with blood culture using samples from a cohort of septic patients with suspicion of BSIs. dPCR showed a great potential to identify the pathogens most commonly associated with BSIs as well as AMR genes, as it was faster and more sensible than mNGS and blood culture [10]. In these previous studies [10, 15, 16], clinical validation revealed that dPCR method was superior to blood culture in terms of specificity, sensitivity, and turnaround time, representing a promising method for the early and accurate diagnosis of BSIs [10, 15, 16]. Our group has established a ddPCR assay capable of detecting and quantifying the housekee** genes of important nosocomial bacterial species in ICUs, such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [17]. These assays are compatible with duplexing, show low replication variability and very low limit of detection (less than 1 pg of DNA) (Fig. 3). Ongoing work is focused on applying the developed ddPCR assays directly to blood and designing a panel that allows testing as many samples at the same time as possible.

The main limitation of dPCR compared with blood culture or mNGS, but not with qPCR, is that it can only detect the pathogens included in the dPCR panels. Nevertheless, the results obtained support that early identification of MDR pathogens by dPCR can improve treatment outcomes [10, 15, 16].

Fungal identification in blood

dPCR has been also tested for the detection of candidemia [42] quantified bacterial DNA load by dPCR (through 16S rDNA), to evaluate if the bacterial density in an ICU environment influenced the establishment of the microbiome in hospitalized premature infants. The authors showed that bacterial DNA load and diversity varied between surfaces. Room-specific microbiome signatures were detected, suggesting that the microbes seeding ICU surfaces are sourced from reservoirs within the room, possible sha** hospitalized infants gut microbiome [42].

Applications of dPCR targeting host response

Results coming from high-throughput technologies such as microarrays or next-generation sequencing, which are able to analyse the entire human transcriptome, have revealed the existence of specific host response signatures potentially useful to improve diagnosis [43], severity stratification and prognosis assessment [44, 45] of severe infection. dPCR is making real the promise of translating these signatures into the clinical practice. A work from our group was pioneer in exploring the potential use of dPCR to diagnose sepsis, evidencing that the gene expression ratio between the constant region of the mu heavy chain of IgM and CD20 yielded an area under the receiver operating curve (AUROC) of 0.72 to differentiate sepsis from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [46]. In turn, Almansa et al. evidenced that the transcriptomic ratios between matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP8) or Lipocalin 2 (LCN2), which are two genes coding for the proteins contained in the neutrophil granules, with the major histocompatibility complex class II, DR alpha molecule (HLA-DRA), yielded AUROCs > 0.89 to differentiate between sepsis and SIRS [47]. The combination of gene expression profiling by dPCR with standard biomarkers commonly used in the clinical practice is also an exciting avenue of research, already explored in another work from Almansa et al., which evidenced that the combination of procalcitonin and HLA-DRA expression levels outperformed the former biomarker to detect sepsis. In this work, procalcitonin yielded an AUROC of 0.80 and the ratio Procalcitonin/HLA-DRA of 0.85 [48]. In a small study, Link et al. explored the potential of microRNA (miRNA) expression quantification by dPCR to diagnose sepsis. These authors found that miR-26b-5p yielded an AUROC of 0.80 to differentiate critically ill patients with sepsis from those with no sepsis [49]. dPCR has been also employed to evaluate the magnitude of the biological processes occurring during sepsis that are difficult to quantify with the currently available methods. For example, in a cohort of patients with infection, sepsis or septic shock, Martin-Fernandez et al. evidenced a progressive increase in the expression levels of emergency granulopoiesis related genes with severity [50]. Another signature of sepsis and sCAP is the depressed expression of those genes involved in the immunological synapse between antigen-presenting cells and T cells [51]. Menéndez et al. demonstrated that dPCR is an useful method to evidence the depressed expression of three of these genes [HLA-DRA, CD40 Ligand (CD40LG) and CD28] in patients with CAP presenting with organ failure [52], while Almansa et al. evidenced that profiling the expression levels of immunological synapse genes was also useful to identify VAP, yielding AUROCs of 0.82 for CD40LG, 0.79 for inducible T cell costimulator (ICOS), 0.78 for CD28 and 0.74 for CD3E [53]. Regarding prognosis, Busani et al. used dPCR to evidence the potential role of mitochondrial DNA as predictor of mortality in patients with septic shock due to MDR bacteria [54]. In turn, Almansa et al. showed that gene expression levels of HLA-DRA quantified by dPCR were an independent predictor of mortality in sepsis [47]. Cajander et al. had already proposed to use expression levels of this gene to identify those sepsis patients that could benefit from immunostimulatory drugs [55]. More recently, using dPCR, Bruneau et al.revealed that expression levels of a circulating ubiquitous RNA (RNase P) correlated with disease severity, invasive mechanical ventilation status and survival in patients with COVID-19 [40]. Also in severe COVID-19, Sabbatinelli et al. found that low levels in plasma of the inflamm-aging associated miRNA miR-146a were associated with no response to tocilizumab [56]. Metabolomics is a relatively new “-omic” that has demonstrated its use in the management of septic patients (e.g. lactate). The combination of this “-omics” approach with the transcriptomics markers measured by dPCR might be useful to determine patient severity, predict the need for mechanical ventilation and mortality [57].

Conclusions

This review evidences the potential of dPCR as a useful tool that could contribute to improve the diagnosis and clinical management of infection in critical care medicine. Although most of the published works consist of pilot/ exploratory studies, they show the potential of dPCR, supporting the development of further, larger studies aimed to validate the use of this technology in this field.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article (and its additional file).

Abbreviations

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance genes

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating curve

- BSIs:

-

Bloodstream infections

- CD40LG:

-

CD40 Ligand

- cfDNA:

-

Cell-free deoxyribonucleic acid

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- ddPCR:

-

Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- dPCR:

-

Digital polymerase chain reaction

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr Virus

- HLA-DRA:

-

Major histocompatibility complex class II, DR alpha molecule

- ICOS:

-

Inducible T Cell Costimulator

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- LCN2:

-

Lipocalin 2

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistance

- miRNA:

-

Micro ribonucleic acid

- MMP8:

-

Matrix metalloproteinase-8

- mNGS:

-

Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing ()

- MTB:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCT:

-

Procalcitonin

- qPCR:

-

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- rDNA:

-

Ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- sCAP:

-

Severe community acquired pneumonia

- SIRS:

-

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

References

Sakr Y, Jaschinski U, Wittebole X, Szakmany T, Lipman J, Ñamendys-Silva SA, et al. Sepsis in intensive care unit patients: worldwide data from the intensive care over nations audit. Open forum Infect Dis. 2018;5.

Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, Sotgiu G, Restrepo MI. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet (London, England). 2021;398:906–19.

Strich JJR, Palmore TTN. Preventing Transmission of Multidrug-Resistant Pathogens in the Intensive Care Unit. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:535–50.

Martin SJ, Yost RJ. Infectious diseases in the critically ill patients. J Pharm Pract. 2011;24:35–43.

Suetens C, Latour K, Kärki T, Ricchizzi E, Kinross P, Moro ML, et al. Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections, estimated incidence and composite antimicrobial resistance index in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities: results from two European point prevalence surveys, 2016 to 2017. Euro Surveill. 2018;23.

Cillóniz C, Torres A, Niederman MS. Management of pneumonia in critically ill patients. BMJ. 2021;375:e065871.

Salipante SJ, Jerome KR. Digital PCR-an emerging technology with broad applications in microbiology. Clin Chem. 2020;66:117–23.

Sreejith KR, Ooi CH, ** J, Dao DV, Nguyen NT. Digital polymerase chain reaction technology—recent advances and future perspectives. Lab Chip. 2018;18:3717–32.

Quan PL, Sauzade M, Brouzes E. dPCR: a technology review. Sensors (Basel). 2018;18.

Hu B, Tao Y, Shao Z, Zheng Y, Zhang R, Yang X, et al. A comparison of blood pathogen detection among droplet digital PCR, metagenomic next-generation sequencing, and blood culture in critically ill patients with suspected bloodstream infections. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:641202.

Buchan BW, Ledeboer NA. Emerging technologies for the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:783–822.

Walter JM, Wunderink RG. Severe respiratory viral infections: new evidence and changing paradigms. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017;31:455–74.

Jung J, Seo E, Yoo RN, Sung H, Lee J. Clinical significance of viral-bacterial codetection among young children with respiratory tract infections: findings of RSV, influenza, adenoviral infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18504.

Yamamoto M, Ushio R, Watanabe H, Tachibana T, Tanaka M, Yokose T, et al. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-derived DNA in circulating cell-free DNA from a patient with disseminated infection using digital PCR. Int J Infect Dis. 2018;66:80–2.

Shin J, Shin S, Jung SH, Park C, Cho SY, Lee DG, et al. Duplex dPCR system for rapid identification of gram-negative pathogens in the blood of patients with bloodstream infection: a culture-independent approach. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;31:1481–9.

Zheng Y, ** J, Shao Z, Liu J, Zhang R, Sun R, et al. Development and clinical validation of a droplet digital PCR assay for detecting Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae in patients with suspected bloodstream infections. Microbiologyopen. 2021;10.

Zaragoza R, Ramírez P, López-Pueyo MJ. Nosocomial infections in intensive care units. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2014;32:320–7.

Chen B, **e Y, Zhang N, Li W, Liu C, Li D, et al. Evaluation of droplet digital PCR assay for the diagnosis of candidemia in blood samples. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:700008.

Zhou F, Sun S, Sun X, Chen Y, Yang X. Rapid and sensitive identification of pleural and peritoneal infections by droplet digital PCR. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2021;66:213–9.

Simms EL, Chung H, Oberding L, Muruve DA, McDonald B, Bromley A, et al. Post-mortem molecular investigations of SARS-CoV-2 in an unexpected death of a recent kidney transplant recipient. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:2590–5.

Alteri C, Cento V, Antonello M, Colagrossi L, Merli M, Ughi N, et al. Detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 by droplet digital PCR in real-time PCR negative nasopharyngeal swabs from suspected COVID-19 patients. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0236311.

Jiang Y, Wang H, Hao S, Chen Y, He J, Liu Y, et al. Digital PCR is a sensitive new technique for SARS-CoV-2 detection in clinical applications. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;511:346–51.

Blot F, Schmidt E, Nitenberg G, Tancrède C, Leclercq B, Laplanche A, et al. Earlier positivity of central-venous- versus peripheral-blood cultures is highly predictive of catheter-related sepsis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:105–9.

Khatib R, Riederer K, Saeed S, Johnson LB, Fakih MG, Sharma M, et al. Time to positivity in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: possible correlation with the source and outcome of infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:594–8.

Kim J, Gregson DB, Ross T, Laupland KB. Time to blood culture positivity in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: association with 30-day mortality. J Infect. 2010;61:197–204.

Fernández-Cruz A, Marín M, Kestler M, Alcalá L, Rodriguez-Créixems M, Bouza E. The value of combining blood culture and SeptiFast data for predicting complicated bloodstream infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria or Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:1130–6.

Choi SH, Chung JW. Time to positivity of follow-up blood cultures in patients with persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:2963–7.

Hsu MS, Huang YT, Hsu HS, Liao CH. Sequential time to positivity of blood cultures can be a predictor of prognosis of patients with persistent Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:892–8.

Ziegler I, Cajander S, Rasmussen G, Ennefors T, Mölling P, Strålin K. High nuc DNA load in whole blood is associated with sepsis, mortality and immune dysregulation in Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Infect Dis (London, England). 2019;51:216–26.

Ziegler I, Lindström S, Källgren M, Strålin K, Mölling P. 16S rDNA droplet digital PCR for monitoring bacterial DNAemia in bloodstream infections. PLoS One. 2019;14.

Bialasiewicz S, Duarte TPS, Nguyen SH, Sukumaran V, Stewart A, Appleton S, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Capnocytophaga canimorsus septic shock in an immunocompetent individual using real-time Nanopore sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:660.

Dickson RP, Schultz MJ, Van Der Poll T, Schouten LR, Falkowski NR, Luth JE, et al. Lung microbiota predict clinical outcomes in critically Ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:555–63.

Goh C, Burnham KL, Ansari MA, de Cesare M, Golubchik T, Hutton P, et al. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in sepsis due to community-acquired pneumonia is associated with increased morbidity and an immunosuppressed host transcriptomic endotype. Sci Rep. 2020;10.

Veyer D, Kernéis S, Poulet G, Wack M, Robillard N, Taly V, et al. Highly sensitive quantification of plasma SARS-CoV-2 RNA shelds light on its potential clinical value. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;

Chen L, Wang G, Long X, Hou H, Wei J, Cao Y, et al. Dynamics of blood viral load is strongly associated with clinical outcomes in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: a prospective cohort study. J Mol Diagn. 2021;23:10–8.

Bermejo-Martin JF, González-Rivera M, Almansa R, Micheloud D, Tedim AP, Domínguez-Gil M, et al. Viral RNA load in plasma is associated with critical illness and a dysregulated host response in COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:691.

Ram-Mohan N, Kim D, Zudock EJ, Hashemi MM, Tjandra KC, Rogers AJ, et al. SARS-CoV-2 RNAemia predicts clinical deterioration and extrapulmonary complications from COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:218–26.

Tedim AP, Almansa R, Domínguez-Gil M, González-Rivera M, Micheloud D, Ryan P, et al. Comparison of real-time and droplet digital PCR to detect and quantify SARS-CoV-2 RNA in plasma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51:e13501.

Martin-Vicente M, Almansa R, Martínez I, Tedim AP, Bustamante E, Tamayo L, et al. Low anti-SARS-CoV-2 S antibody levels predict increased mortality and dissemination of viral components in the blood of critical COVID-19 patients. J Intern Med. 2022;291:232–40.

Bruneau T, Wack M, Poulet G, Robillard N, Philippe A, Puig P-L, et al. Circulating ubiquitous RNA, a highly predictive and prognostic biomarker in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;

Chanderraj R, Brown CA, Hinkle K, Falkowski N, Woods RJ, Dickson RP. The bacterial density of clinical rectal swabs is highly variable, correlates with sequencing contamination, and predicts patient risk of extraintestinal infection. Microbiome. 2022;10.

Brooks B, Olm MR, Firek BA, Baker R, Geller-McGrath D, Reimer SR, et al. The develo** premature infant gut microbiome is a major factor sha** the microbiome of neonatal intensive care unit rooms. Microbiome. 2018;6.

Sweeney TE, Shidham A, Wong HR, Khatri P. A comprehensive time-course-based multicohort analysis of sepsis and sterile inflammation reveals a robust diagnostic gene set. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7.

Scicluna BP, van Vught LA, Zwinderman AH, Wiewel MA, Davenport EE, Burnham KL, et al. Classification of patients with sepsis according to blood genomic endotype: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:816–26.

Sweeney TE, Perumal TM, Henao R, Nichols M, Howrylak JA, Choi AM, et al. A community approach to mortality prediction in sepsis via gene expression analysis. Nat Commun. 2018;9.

Tamayo E, Almansa R, Carrasco E, Ávila-Alonso A, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Wain J, et al. Quantification of IgM molecular response by droplet digital PCR as a potential tool for the early diagnosis of sepsis. Crit Care. 2014;18.

Almansa R, Ortega A, Ávila-Alonso A, Heredia-Rodríguez M, Martín S, Benavides D, et al. Quantification of immune dysregulation by next-generation polymerase chain reaction to improve sepsis diagnosis in surgical patients. Ann Surg. 2019;269:545–53.

Almansa R, Martín S, Martin-Fernandez M, Heredia-Rodríguez M, Gómez-Sánchez E, Aragón M, et al. Combined quantification of procalcitonin and HLA-DR improves sepsis detection in surgical patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8.

Link F, Krohn K, Burgdorff AM, Christel A, Schumann J. Sepsis diagnostics: intensive care scoring systems superior to MicroRNA biomarker testing. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2020;10.

Martin-Fernandez M, Vaquero-Roncero LM, Almansa R, Gómez-Sánchez E, Martín S, Tamayo E, et al. Endothelial dysfunction is an early indicator of sepsis and neutrophil degranulation of septic shock in surgical patients. BJS open BJS Open. 2020;4:524–34.

Davenport EE, Burnham KL, Radhakrishnan J, Humburg P, Hutton P, Mills TC, et al. Genomic landscape of the individual host response and outcomes in sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:259–71.

Menéndez R, Méndez R, Almansa R, Ortega A, Alonso R, Suescun M, et al. Simultaneous depression of immunological synapse and endothelial injury is associated with organ dysfunction in community-acquired pneumonia. J Clin Med. 2019;8.

Almansa R, Nogales L, Martín-Fernández M, Batlle M, Villareal E, Rico L, et al. Transcriptomic depression of immunological synapse as a signature of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:415–415.

Busani S, De Biasi S, Nasi M, Paolini A, Venturelli S, Tosi M, et al. Increased plasma levels of mitochondrial DNA and normal inflammasome gene expression in monocytes characterize patients with septic shock due to multidrug resistant bacteria. Front Immunol. 2020;11.

Cajander S, Tina E, Bäckman A, Magnuson A, Strålin K, Söderquist B, et al. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction measurement of HLA-DRA gene expression in whole blood is highly reproducible and shows changes that reflect dynamic shifts in monocyte surface HLA-DR expression during the course of sepsis. PLoS One. 2016;11.

Sabbatinelli J, Giuliani A, Matacchione G, Latini S, Laprovitera N, Pomponio G, et al. Decreased serum levels of the inflammaging marker miR-146a are associated with clinical non-response to tocilizumab in COVID-19 patients. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;193.

Evangelatos N, Bauer P, Reumann M, Satyamoorthy K, Lehrach H, Brand A. Metabolomics in sepsis and its impact on public health. Public Health Genomics. 2017;20:274–85.

Funding

This work was funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), (Project Code PI19/00590), co-funded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) · European Social Fund (ESF), "A way to make Europe"/"Investing in your future") (JFBM), and also by a Research Grant 2020 from ESCMID (APT). APT, IM and AF salaries were funded by the Sara Borrell Research Grant (CD18/00123), Río Hortega (CM18/00157) and PFIS (FI20/00278) Research Grants, respectively, from ISCIII and co-funded by ERDF/ESF, "A way to make Europe"/"Investing in your future").

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JFBM designed the review. IM and APT looked for bibliography and wrote the manuscript. APT, IM, AF developed the ddPCR works; MDG and JME collected the strains used for ddPCR pilot study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison of techniques to detect microorganisms that can be employed to diagnose the most common infections affecting critically ill patients. Table containing description of emerging and current techniques to detect microorganism that can be applied to the most common critically ill patients’ infections, including the most important advantages and disadvantages.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Merino, I., de la Fuente, A., Domínguez-Gil, M. et al. Digital PCR applications for the diagnosis and management of infection in critical care medicine. Crit Care 26, 63 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03948-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-03948-8