Abstract

Background

There are currently no models for the transition of patients with metabolic bone diseases (MBDs) from paediatric to adult care. The aim of this project was to analyse information on the experience of physicians in the transition of these patients in Spain, and to draw up consensus recommendations with the specialists involved in their treatment and follow-up.

Methods

The project was carried out by a group of experts in MBDs and included a systematic review of the literature for the identification of critical points in the transition process. This was used to develop a questionnaire with a total of 48 questions that would determine the degree of consensus on: (a) the rationale for a transition programme and the optimal time for the patient to start the transition process; (b) transition models and plans; (c) the information that should be specified in the transition plan; and (d) the documentation to be created and the training required. Recommendations and a practical algorithm were developed using the findings. The project was endorsed by eight scientific societies.

Results

A total of 86 physicians from 53 Spanish hospitals participated. Consensus was reached on 45 of the 48 statements. There was no agreement that the age of 12 years was an appropriate and feasible point at which to initiate the transition in patients with MBD, nor that a gradual transition model could reasonably be implemented in their own hospital. According to the participants, the main barriers for successful transition in Spain today are lack of resources and lack of coordination between paediatric and adult units.

Conclusions

The TEAM Project gives an overview of the transition of paediatric MBD patients to adult care in Spain and provides practical recommendations for its implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The process of transition from paediatric to adult care has acquired considerable interest in recent years in patients with childhood-onset chronic diseases [1]. The lack of coordination between specialists and paediatric and adult services, which is well documented in the literature, and the lack of proper training in the transition process, make clinical management of adolescent patients more difficult, and may have a negative impact on their disease [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Consultation with the patient during the transition period requires designating the necessary time to foster mutual respect, promote independence in the management of their disease, strengthen the doctor-patient relationship, and thus treat not only the patient’s underlying condition, but also important health-related aspects beyond the disease itself [4, 8, 10,11,12].

Process planning coordinated between paediatric and adult specialists—widespread in diseases such as diabetes or arthritis, but in its infancy in some metabolic bone diseases (MBDs) [13]—has been shown improve quality of care, although further studies are still needed to assess the quality and effectiveness of transition programmes [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. There is therefore a broad consensus that this planning should be considered in patients with any chronic disease [1]. In fact, the need to develop transition programmes for adolescents with chronic diseases to prevent deterioration in their health is defined in different regulations in United Kingdom, Canada and the United States [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

Nevertheless, despite the fact that physicians agree on the need for transition programmes [3], they are rarely applied in clinical practice [37, 38], and fewer than 15% of adolescents who could be included actually participate in these schemes [39].

Although different scientific societies have developed consensus documents, guidelines and recommendations in recent years to guide the rollout of transition units, there are still not defined transition models for patients with MBDs, from the most common entities such as secondary osteoporosis or osteogenesis imperfecta, to the rarest such as acquired and congenital hypophosphataemic rickets or X-linked hypophosphataemia (XLH).

In the specific case of XLH, because there is no clear consensus on how to make the transition from paediatric to adult-oriented care, many questions remain to be answered in future guidelines or recommendations. One of these questions concerns the right age to begin the transition process from paediatric to adult care. In this respect, Dahir et al. suggest that preparation for transition can begin when patients with XLH are around 12 years old, and continue until transfer to care by adult clinicians at approximately 18–26 years [13]. Consensus, furthermore, needs to be reached on how this transition should be approached and managed in a multidisciplinary manner by the medical/care team, due to the multisystemic nature of XLH [40, 41]. Some recently published European consensus documents and guidelines on the management of patients with XLH have highlighted the need to implement and anticipate a multidisciplinary approach to transition [42,43,44]. In the Belgian setting, similar to Spain in that the treatment of MBD does not fall under the umbrella of a specific medical specialty recognized as such, it has been suggested that several specialties should be involved, either in the routine follow-up or as possible interdepartmental consultation. These should be both paediatric and adult specialties, including endocrinologists, nephrologists, rheumatologists, orthopaedics specialists, neurosurgeons, radiologists, geneticists, specialists in physical medicine and rehabilitation, dentists, orthodontists and maxillofacial surgeons, and even urologists, otorhinolaryngologists and ophthalmologists [42]. However, it should be noted that more barriers or difficulties than usual may be encountered in managing the transition in patients with XLH, due to a lack of knowledge about the disease among many of the specialists potentially involved in it.

The objective of the TEAM Project (Transición a la Edad Adulta de pacientes con enfermedades Metabólicas óseas, Transition to adult care of patients with metabolic bone diseases) was to seek the views and experience of physicians regarding the existing transition units in Spain for patients with MBD or similar disease processes, in order to identify and define areas for improvement, and to develop practical recommendations for patient management in the transition to adult care that are presented in this document.

Methods

Study design and ethical standards

A committee of nine experts in MBD in children (paediatric rheumatology, nephrology and endocrinology) and adult specialists (rheumatology and internal medicine) was selected in base of their expertise and scientific background in bone metabolism. The objectives of the committee were:

-

To analyse the information from a systematic literature review on transition units, and, more specifically, in patients with MBD. For this review, a systematic review protocol was designed to identify consensus-type articles, guidelines, and systematic reviews in Spanish and English, following PRISMA guidelines [45]. The websites of various international institutions with information on transition programmes for children and adolescents with different diseases were also consulted. The experts committee discussed on networking the systematic review documents to be discussed in next steps.

-

To define the indicators that would be submitted to a Delphi consensus process. One face-to-face meeting was completed to select 48 questions grouped into five survey sections (Additional file 1). The survey was checked out by the experts and their local teams. After one online meeting, the final survey was obtained. The survey was distributed to medical specialists from eight scientific societies on a website that met the CHERRIES quality standards for electronic questionnaires [46].

-

To develop a series of recommendations for the management of patients with MBD during the transition period, based on the results of the consensus. Two online experts’ meetings were needed for the recommendation’s consensus.

The action in patients with XLH was specifically asked about, since this is considered to be the MBD entity with the greatest effect on different organs and systems, and the one that requires more intense clinical follow-up at the transition age.

The TEAM Project was authorized by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí de Sabadell (Spain) on 28-07-2020 (Reference 2020/695). Data were collected from 1 June to 10 December 2021.

Participants

The questionnaire was completed by physicians involved in the management of patients with MBD during the period of transition to adult care. Physicians were members of one of the scientific societies that endorsed the project: AECOM (Spanish Association for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism), AENP (Spanish Association of Paediatric Nephrology), SEEN (Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition), SEEP (Spanish Society of Paediatric Endocrinology), SEIOMM (Spanish Society of Bone and Mineral Metabolism Research), SEMI (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), SEN (Spanish Society of Nephrology) and SERPE (Spanish Society of Paediatric Rheumatology).

Statistical methods

The questionnaire included four types of questions: multiple choice, quantitative response, free text, and questions to indicate the degree of agreement on a scale of 1–10 points, where the value 1 represents “no agreement” and the value 10 represents “total agreement” with the statement of the question. The results of the multiple-choice questions are shown as the number and proportion of participants who chose each answer. Free text questions were coded into categories and described in the same way as above. Quantitative questions are shown as number of responses, mean value, and 95% confidence interval (CI). The results of the questions about the degree of agreement with a statement were analysed quantitatively, expressing the mean score of the degree of agreement, and the proportion of participants who responded to each category from 1 to 10 was calculated. Consensus was considered to have been reached on each statement when at least 70% of the participants rated their agreement at ≥ 7 points. IBM-SPSS 27.0 software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

A total of 86 physicians from 53 hospitals located in 23 Spanish provinces participated, with representation from most autonomous regions of the country.

Almost all the respondents (97.7%) had experience in managing patients with MBD, with 52.3% being part of a transition unit, clinic or programme. The mean age of participants was 47 years and 55.8% were women. Half were paediatricians (52.3%) and 40.7% were adult physicians working in public hospitals (87.2%). The most common specialty of the physicians surveyed was nephrology (43%), followed by endocrinology (20.9%), rheumatology (16.3%), paediatric medicine (12.8%) and internal medicine (7%). Doctors had an average of 18 years of experience in their specialty, and 23.1% (95% CI 15.1–31) of patients in their clinics had been diagnosed with MBD.

Consensus was reached in a single round of the Delphi questionnaire. Table 1 describes the results of the consensus questions on the implementation and timing of the transition. Consensus was reached on all but two statements: “It is appropriate to start the transition programme at 12 years of age in patients with MBD", which obtained a mean score of 5.42 (95% CI 4.8–6), with agreement reached in 36% of physicians; and the statement “It is feasible to start the transition programme at 12 years of age in patients with MBD”, with a mean score of 5.1 (95% CI 4.5–5.7), and agreement was reached in 29.4% of participants.

Table 2 shows the consensus results on the indicators for the model and transition plan, where consensus was reached on all but one question: “Is the transition model you selected as your preferred model feasible in your setting?” A mean score of 7.1 (95% CI 6.6–7.6) was obtained and consensus was reached in 68.6% of participants.

Consensus was reached on all statements regarding the information needed in the transition program (Table 3).

With regard to the statements on the documents needed and training on transition, consensus was reached on all the questions posed (Table 4).

Discussion

Rationale for the transition programme and start time

Today, the need for successful healthcare transition is recognized in most chronic diseases, including MBDs. There is evidence that the process of transition to adult care in children/adolescents with chronic diseases is associated with a deterioration in their health [2, 4,5,6,7, 47, 48]. Furthermore, if the disease is diagnosed during adolescence, it will have a great physical and psychological impact on the adolescent [49]. Several surveys of adolescents with different chronic diseases and their parents highlight the need for interventions that minimize the risk of deteriorating the health status of children when they access adult services [37, 47, 50, 51]. Likewise, patients with bone diseases are monitored by different paediatric and adult specialists, depending on the disease and/or hospital, further complicating successful transition.

As described in other consensus documents [52, 53], there is also agreement among the physicians surveyed on the need for a transition programme, since the majority (97.7%) believe that they understand what a transition unit or programme is, and the same proportion consider it necessary to create a care transition programme for children with MBD. However, the percentage of agreement decrease to 75.6% when participants are asked whether it is feasible to establish a transition programme in children with MBD in their setting (Table 1).

One of the most controversial questions surrounding the transition process was the age at which it should begin. The answer is difficult, since it is a dynamic process that begins in early adolescence and ends when the patient is fully integrated into an adult unit. Most transition guidelines suggest that the process should begin when the patient is 13 or at most 14 years old [54], so that they can familiarize themselves with the adult unit prior to transfer and improve their readiness for it. In the consensus paper by Pérez-Lopez et al. in patients with inborn errors of metabolism, the authors concluded that the transition should be made at the age of 16–18 years, when the disease is in a stable phase, while taking into account the patient's level of development [55].

Although the American scientific literature considers 12 years as the recommended age for transition [56], the physicians surveyed considered that this age was neither appropriate nor feasible in Spain. For them, the most appropriate average age for initiating the transition of patients with MBD is 14.7 years, similar to that suggested for patients with XLH (14.6 years). We believe that the age of initiation should be flexible and appropriate to adolescent’s level of development and dependence. In this regard, it has been observed that doctors often consider that the patient is ready to be seen independently at an earlier age than the parents believe; therefore, a consensual decision should be sought, and the adolescent should be evaluated to determine if they are ready for transfer [9, 57,58,59].

Sometimes, a dependency relationship is created between the patient and parents and the paediatrician, which undermines the autonomy that the patient should be acquiring. This is because both the patient and their family perceive care in the adult unit to be of lower quality and tend to distrust it [60].

We found no references to the age of transition associated with the adolescent's gender. Physical maturation is reached 2–3 years earlier in females, and may also be accompanied by greater psychological maturity that could make transition at a younger age more viable than in males.

There was agreement on the need to use validated scales to evaluate whether the adolescent is ready to start their follow-up in adult specialties, both in the literature [61, 62] and among the physicians consulted in the survey (73.3%). However, there are few scales available to measure this variable, so the psychologist support should be desirable at this point.

Recommendations

-

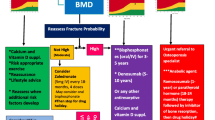

Parents and patients should be informed about the start of the transition process at age 12, and the process should begin at the age of 14 (Fig. 1).

-

The adolescent and their family should be assessed to determine whether they are ready to begin the transition.

-

Transition should begin when the patient’s metabolic bone disease is in a stable phase.

Transition model and transition plan

The survey found that 65% of respondents did not have a transition model or plan at their facility (Table 2), although 97.7% believed it necessary (Table 1).

Different transition models have been described, depending on whether the patient transfer is done directly (paediatric and adult medicine function independently and the patient is transferred with a medical report), gradually (there is a shared period between paediatric and adult medicine, which can involve joint or overlap** visits between paediatrics and the adult service), or models in which the same paediatrician manages the patient continuously throughout their paediatric and adult care. In all models, the possibility of interaction and collaboration between services is maintained once the transfer is complete (Fig. 2) [9, 63]. Most participating physicians (88.4%) preferred the transition model that consists of a gradual transfer to the adult specialist, with multidisciplinary paediatric-adult consultation during the transition. However, when asked if this model would be feasible in their hospital, the average agreement score was 7.1 points (95% CI 6.6–7.6), and only 68.6% of doctors rated their agreement above 7 points; thus, there was considered to be no agreement on this statement.

In the systematic review of the different transition models, the results were inconclusive on the differential benefit between them [1], due to various limitations: it was based on four small studies, with a limited number of clinical disorders, and follow-up of less than 12 months; moreover, the studies did not report on the specific clinical outcome resulting from use of the model in the disorder. Therefore, one model was not proven to be better than another.

Although there was agreement on the question of whether there should be a transition manager, with 95.3% of the participants rating their agreement above 7 points, a smaller proportion of doctors (74.4%) believed that it would be feasible to appoint such a person in their setting (Table 2). The existence of a contact person has been associated with higher transition success rates in patients with chronic diseases [20].

Ideally, transition units should be made up of a multidisciplinary group of healthcare professionals who coordinate and accompany the adolescent's transition to adult care. When participating physicians were asked whether multidisciplinary working groups should be created for the management of adolescents with metabolic diseases, there was consensus on the statement (mean agreement score of 9.1), with 95.3% of physicians scoring their agreement above 7 points. However, the proportion of physicians who believe it is feasible to create such groups in their setting was smaller (81.4%).

Therefore, there is a perceived need to set up multidisciplinary teams and appoint transition programme managers or case managers to facilitate the process, even though 8 out of 10 physicians feel it is not feasible in their setting. One of the reasons could be that specialists may be practising in different hospitals that may not share the patient's electronic record, complicating coordination between specialists, but respondents felt that the issue was mainly a lack of economic and human resources (Fig. 3).

Although the current literature on transition for chronic diseases is quite extensive in general, so far only a few hospitals have created specific programmes to ensure that transitional care for adolescents and young adults is offered in a coordinated, formalized, and standardized manner [54, 64,65,66]. An MBD team is defined as a core multidisciplinary group, consisting of a paediatrician/adult physician, specialized nurse and/or case manager, metabolic dietician, and a physical and rehabilitative medicine specialist, that has access to other specialists such as psychologists and social workers. Each of these various members must contribute towards providing complete information to the patient and their family, facilitated by close contact with the specialist nurse together with a detailed and comprehensive clinical report for the new team.

The ideal situation would be to ensure that, during the transition, all young people receive uninterrupted, comprehensive and accessible care within their community, so that their health does not deteriorate during this period.

Recommendations

-

The most suitable transition model for monitoring the patient's disease should be studied and confirmed to be feasible in the particular setting.

-

A case manager should be assigned to coordinate the different appointments that the patient must attend during their follow-up.

-

The creation of multidisciplinary teams consisting of specialists relevant to the patient's disease is recommended. In the case of patients with MBD, this could be paediatricians and adult nephrologists, endocrinologists, rheumatologists, internal medicine and rehabilitation specialists in bone metabolism, specialized nurses and/or case managers, metabolic dieticians, physical and rehabilitative medicine specialists, psychologists and social workers.

Information that should be specified in the transition programme

A patient who is informed about their disease and about their clinical follow-up and therapeutic alternatives will have greater decision-making capacity and will be more willing to comply with treatment. Patients want to know more about their disease, its symptoms, treatments and prognosis, but also about what other people in their situation do and feel, and they use any means at their disposal to achieve this, including information found on the internet, which can often create greater confusion.

With the right information, patients and families acquire training, empower themselves, and take full responsibility for the disease. To this end, an appropriate, gradually implemented transition programme is critical, and both families and the patient should be aware of it from the time of diagnosis (Fig. 1, point 1). The consensus on this point was 73.3% (Table 3), but this may be due to the fact that the diagnosis of some genetic diseases is made very early in life, and both the paediatrician and the family go through a difficult time, the professional in communicating information, and the family in coming to terms with a chronic disease diagnosis that may have a course and prognosis that are not always predictable. In this context, it is not surprising that the transition programme may be pushed into the background, awaiting a more stable situation. Patients should be informed and accompanied step-by-step as they gradually move from paediatric care in which physicians and caregivers are responsible for the patient in all aspects ranging from making medical appointments to administering medication, to adult care, in which the patient is aware of all recommendations, precautions and treatments needed to control their disease and avoid preventable complications and deterioration. These factors have been examined in a small study carried out in relatives and patients with rheumatic diseases [67].

Accordingly, in the initial phase of diagnosis and planning, both parents and patient should be informed (Fig. 1, point 1). The next step is to move on to a phase of training and further evaluation of the knowledge acquired for self-management (Fig. 1, points 2 and 3).

In this second phase, we recommend providing material, either written or digital, for both the parents and the adolescent (Fig. 1, point 4). Thus, the survey (Table 3) found 83.7% consensus on the need for a written report for the parents, and 81.4% for the adolescent, and a greater consensus (91.9%) that the report should contain information on names and contact details of the nurse, social worker, case manager and patient associations (Fig. 1, points 4 and 7). There was also consensus that the report should specify the visit and test schedule, the distinctive characteristics of treatment in adults (Fig. 1, point 5), information on the epidemiology, diagnosis and prognosis of the disease, and healthy lifestyle recommendations (Fig. 1, point 4). There was 83.7% consensus on the need for a personalized card for possible emergencies (Fig. 1, point 6), and 95.3% consensus on the importance of identifying specific indicators of disease control and treatment adherence.

The survey confirmed agreement on the need to plan adolescent consultations without parents (84.9%). Likewise, the ability to understand the disease and its treatments should be assessed (95.3%), as well as the satisfaction of the adolescent (91.9%), who should be encouraged to become an expert patient, well acquainted with his/her disease and of any new developments that may arise, and one who actively participates in decision-making. The adolescent’s satisfaction should be assessed periodically (at least annually) with validated scales [68], and it would also be desirable to assess the degree of training of the patient and their family in relation to disease management. The role of nursing (93%) and social work (74.4%) was highly valued for the success of the transition programme.

Recommendations

-

It is recommended that a written transition plan be created, facilitating communication between the patient, parents and case manager with the specialist during the transition period and throughout the patient's follow-up.

-

It is recommended that documents be created for the patient and their parents or guardians that contain information specific to the patient’s disease, as well as contact details for those responsible for the patient’s care during the transition.

-

Templates should be created for documents such as the clinical report for transfer from paediatrics to adult specialists and a guide for action in case of emergencies and acute decompensation.

Transition plan documents and expert training

To make the clinical transition to adult care, there was consensus among the respondents that a unifying document should be prepared that includes the materials that will be given to parents and patients, the main milestones in the history of the patient's MBD, and sufficient information to provide parents and patients with access to all the professionals involved in their care. It is important to have a standardized model that lists the documents and data summarized in Fig. 1. Some good examples for the preparation of these materials can be found in a series of websites that contain information and resources for the development of clinical transition programmes from paediatric to adult care (Table 5).

A key component of transitional care is the availability of appropriately trained personnel with skills and knowledge in the area. In fact, some studies suggest that the determinants of satisfaction among adolescents in transition include the availability of qualified staff, rather than the characteristics of the physical setting and problems during the process [9]. Unfortunately, however, professionals with knowledge of the transition process are not always available in many hospitals, and most respondents (Table 4) emphasized the need for training of paediatricians and adult specialists in the transition (95.3%), even in the form of regulated accreditation, although a lower degree of consensus was reached on this point (79.1%). It is understood that training should include both theoretical foundation training and care experience in functional transition units.

Training of a qualified team can not only help facilitate the patient’s transition, but can also serve to as a point of reference in the process, unifying referral, evaluation and follow-up criteria. It brings in not only specialist doctors and/or nurses, but also other figures such as psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons, and others whose participation is necessary in MBDs, and, in general, in any chronic disease that may involve some degree of disability/adaptation at such a critical stage as adolescence [53]. When planning a new transition unit, it may be useful to identify professionals who may be interested in transitional care and support them in their training, or find services located within the same hospital or referral hospital with already formed transition units [8].

Recommendations

The following materials should be included in the transition programme (Fig. 1):

-

A letter of information for parents to be given at the time of diagnosis, or when the child is still under 12 years of age (Fig. 1, point 1), informing them about the future transition programme.

-

A letter of information about the transition programme for the parents and another for the adolescent to be given when the child is between the ages of 12 and 18 (Fig. 1, points 2 and 3).

-

The letter should include a summary of information about the disease for the patient and their family that includes general information about their disease, the general testing schedule and frequency of visits based on age, and access to medical societies and patient associations (Fig. 1, point 4).

-

A clinical and progress report of the patient initiated by the paediatrician that will be transferred to the adult specialist (Fig. 1, point 5).

-

A medical emergency card (Fig. 1, point 6) to be given to the patient.

-

A contact card (Fig. 1, point 7) with the name and contact details of the case manager, paediatric and adult specialists, nurse manager and social worker.

Barriers and evaluation of the effectiveness of the programme

For the development and implementation of a transition programme for patients with MBD, it is essential to identify any barriers that hinder this process and analyse how to address them [68].

The main barriers according to our survey are: (1) lack of resources (43.3%); (2) poor coordination and communication between paediatrics and adult services (19.3%); (3) some factors related to the low prevalence of MBD (12.9%); and (4) other barriers related to the adult specialty (11.2%) (Fig. 3).

To address the main barrier, human resources, administrative support, time dedicated to the transition, a suitable space, materials and adequate funding are required.

The poor coordination between paediatric and adult specialists may be explained by differences in patient management. The chronic paediatric patient receives supervised and monitored care. However, adult care involves multiple specialists that are usually poorly coordinated, generating “fragmented care”, which leads to a loss of confidence by the patient. A poorly coordinated transition results in confusion, lack of therapeutic compliance, emergency admissions and dependence on external caregivers [68]. A coordinated and gradual transition will build the adolescent’s confidence in the new team.

A central professional figure (nurse or case manager) capable of coordinating and acting as a link between specialists is important, guaranteeing continuity of care and prompt and effective information for the patient [64].

To address factors related to the low prevalence of MBD, training activities for professionals, patients and family members should be promoted, and specific clinical guidelines should be developed.

Regarding factors related to the adult specialty, the adult specialist often has limited knowledge of rare congenital MBDs, and their patients may arrive without a personalized plan or complete medical report from paediatrics. They may also lack skills for communicating with adolescents [3].

These difficulties are very similar to those reported in a study of internal medicine specialists on transition in general, the most relevant being the lack of training/knowledge of chronic childhood diseases [69]. We therefore believe that a transition programme should be established in coordination with the management teams, and that they should be provided with the necessary resources for implementation.

Once the transition programme has been created, it will be necessary to define quality and effectiveness indicators, and to gather this information periodically in order to carry out adequate quality control and continuous improvement [4, 8, 70].

The 2016 Cochrane review of the effectiveness of transition interventions recommended the evaluation of disease-specific patient outcomes as the primary outcome and, as secondary outcomes, the patient's readiness for the process, their satisfaction, treatment adherence, health-related quality of life, disease-related knowledge, self-advocacy skills, improvement in their safety, and healthcare resource use and costs [1, 68].

The effectiveness of the transition process should be evaluated by a dedicated questionnaire for patients and families in close collaboration with the coordinator. The satisfaction of the patient with the program as well as the trust in the whole team needs to be assessed by the coordinator and/or the specialised nurse or case manager. In addition, the program itself must put in place the mechanism to assess the compliance with the follow-up plan and the adherence to treatment until the transition is completed, a fact that must be highly individualized.

Recommendations

-

Barriers in the hospital to implementing a transition programme should be identified, the most common being lack of resources, lack of coordination between paediatricians and adult physicians, lack of knowledge about rare diseases and lack of skills for communicating with the adolescent.

-

Indicators or parameters should be designed to assess the effectiveness of the programme: complete documents that help the adult specialist to provide proper follow-up, patient support measures, identification of results that point to worsening of disease control, patient satisfaction survey and assessment of health-related quality of life.

Conclusions

Despite growing interest in the transition of patients with chronic diseases from paediatric to adult care, few programmes are described in detail in the literature [64, 71,72,73,74]. The aim of the TEAM Project was to analyse the critical points during the transition process and to provide practical recommendations for creating a transition plan for children with MBD.

The limitations of the project were related to the number of doctors who eventually participated in the consensus, which was hampered by the emergence in 2020 of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, although the high degree of consensus obtained on the vast majority of the questions posed strengthens the findings. It would have been desirable to have the participation of other professionals involved in the transition process, such as nurses, psychologists and social workers, who were considered essential by physicians who responded to the survey. Likewise, obtaining information from families and patients would have complemented the opinion and needs of all those involved. The implication of the patient’s associations should also have been very relevant. The work carried out among the professionals responsible for this area could be an important initial step in setting up a comprehensive transition project that substantially takes into account the opinion of all stakeholders.

After creating the essential materials needed to establish a transition plan, the pertinent professionals must be informed of their availability and encouraged to use them. Facilitating the administrative process for parents and patients, giving priority to adolescent appointments during the transition period and avoiding duplication of visits and testing will contribute to the success of the programme and better patient care.

Twelve reviews assessing the effectiveness of transition programmes were identified: six focused on specific diseases such as diabetes [14, 15], palliative care [16], mental health [17], and spina bifida [18, 19], one review looked at chronic diseases [20], three reviews included studies in which patients had a range of medical needs or disabilities [21,22,23], and two reviews summarized evidence from qualitative studies on patients' perspectives [24, 25]. All reviews concluded that to reach valid conclusions, studies evaluating interventions require better designs that feature quantifiable quality and effectiveness indicators to demonstrate the extent of their benefits for patients and society, determined before and after starting the intervention programme.

The TEAM Project provides an overview of the transition of young patients with MBD to adult care in Spain and provides practical recommendations for implementing a transition model. However, before implementing this transitional approach, the endorsement of the patient's associations will be desirable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission from Kyowa Kirin Farmacéutica Data are located in controlled access data storage at E-C-BIO (https://www.ecbio.net).

References

Campbell F, Biggs K, Aldiss SK, O’Neill PM, Clowes M, O’Neill PM, et al. Transition of care for adolescents from paediatric services to adult health services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009794.pub2.

Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, Ackland FM, Brown RS, Fox CT, et al. Current methods of transfer of young people with Type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet Med. 2002;19(8):649–54.

McDonagh JE, Southwood TR, Shaw KL. Unmet education and training needs of rheumatology health professionals in adolescent health and transitional care. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:737–43.

Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, Sananes R, Ritvo PG, Siu SC, et al. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e197-205.

Watson AR. Problems and pitfalls of transition from paediatric to adult renal care. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20(2):113–7.

Busse FP, Hiermann P, Galler A, Stumvoll M, Wiessner T, Kiess W, et al. Evaluation of patients’ opinion and metabolic control after transfer of young adults with type 1 diabetes from a paediatric diabetes clinic to adult care. Hormone Res Paediatr. 2007;67(3):132–8.

Yeung E, Kay J, Roosevelt GE, Brandon M, Yetman AT. Lapse of care as a predictor for morbidity in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2008;125(1):62–5.

Castrejón I. Unidades de transición para pacientes con patología reumática: revisión de la literatura. Reumatol Clin. 2012;8:20–6.

Calvo I, Antón J, Bustabad S, Camacho M, de Inocencio J, Gamir ML, et al. Consensus of the Spanish society of pediatric rheumatology for the transition management from pediatric to adult care in rheumatic patients with childhood onset. Rheumatology. 2015;35:1615–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3273-6.

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Bridging the gap: health care for adolescents. Royal College of Psychiatrists Council Report CR114. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2003. Available at: www.rcpch.ac.uk.

Klostermann BK, Slap GB, Nebrig DM, Tivorsak TL, Britto MT. Earning trust and losing it: adolescents’ views on trusting physicians. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:679–87.

Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Young people‘s satisfaction of transitional care in adolescent rheumatology in the UK. Child Care Health Dev. 2007;33:368–79.

Dahir K, Dhaliwal R, Simmons J, Imel EA, Gottesman GS, Mahan JD, et al. Health care transition from pediatric- to adult-focused care in X-linked hypophosphatemia: expert consensus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(3):599–613. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab796.

Fleming E, Carter B, Gillibrand W. The transition of adolescents with diabetes from the children’s health care service into the adult health care service: a review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(5):560–7.

Findley MK, Cha E, Wong E, Spezia Faulkner M. A systematic Review of transitional care for emerging adults with diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:e47–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.019.

Doug M, Adi Y, Williams J, Paul M, Kelly D, Petchey R, et al. Transition to adult services for children and Young people with palliative care needs: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2011;1(2):167–73.

Paul M, Street C, Wheeler N, Singh SP. Transition to adult services for young people with mental health needs: a systematic review. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;20(3):1–22.

Binks JA, Barden WS, Burke TA, Young NL. What do we really know about the transition to adult-centered health care? A focus on cerebral palsy and spina bifida. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(8):1064–73.

Kelly MS, Thibadeau J, Struwe S, Ramen L, Ouyang L, Routh J. Evaluation of spina bífida transitional care practices in the United States. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2017;10:275–81. https://doi.org/10.3233/PRM-170455.

Chu PY, Maslow GR, von Isenburg M, Chung RJ. Systematic review of the impact of transition interventions for adolescents with chronic illness on transfer from pediatric to adult healthcare. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30:e19-27.

Bloom SR, Kuhlthau K, Van Cleave J, Knapp AA, Newacheck P, Perrin JM. Health care transition for youth with special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51:213–9.

Crowley R, Wolfe I, Lock K, McKee M. Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(6):548–53.

Forbes A, While A, Ullman R, Lewis S, Mathes L, Griffiths. A multi-method review to identify components of practice which may promote continuity in the transition from child to adult care for young people with chronic illness or disability. Report for the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). 2002;1–109.

Fegran L, Hall EO, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H, Ludvigsen MS. Adolescents’ and young adults’ transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: a qualitative metasynthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(1):123–35.

Lugasi T, Achille M, Stevenson M. Patients’ perspective on factors that facilitate transition from child-centered to adult centered health care: a theory integrated metasummary of quantitative and qualitative studies. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(5):429–40.

AAP. American Academy of Family Physicians and American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine. A consensus statement on health care transitions for young adults with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2002;2002(110):1304–6.

CPS. Canadian Paediatric Society. Care of adolescents with chronic conditions. Paediatr Child Health. 2006;11(1):43–8.

CSCI. Commission for Social Care Inspection. Growing up matters: better transition planning for young people with complex needs. Available from: http://www.yorkshirefutures.com/what˙works/growing-mattersbetter-transition-planning-young-people-complex-needs. London: Commission for Social Care Inspection; 2007.

DH. Department of Health, Department for Education and Skills. National service framework for children, young people and maternity services. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH˙4089101. Department of Health; 2004.

DH. Department of Health, child health and maternity services. transition: getting it right for young people. Improving the transition of young people with long-term conditions from children’s to adult health services. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH˙4132145. London: Department of Health Publications; 2006.

DH. Department for Children, Schools and Families & Department of Health/Children’s Mental Health Teams. Kee** children and young people in mind—the Government’s full response to the independent review of CAMHS. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH˙110785 January 2010.

DH, 2013. Department of Health. Improving Children and Young People’s Health Outcomes: a system wide response. Available from: http://bit.ly/10PSvjR February 2013.

RCN Adolescent Health. Royal College of Nursing Adolescent Health Forum. Adolescent transition care. Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/data/assets/pdf˙file/0011/78617/002313.pdf. Royal College of Nursing; 2004.

RCN. Royal College of Nursing. Lost in transition: moving young people between child and adult health services. Available from: http://www.rcn.org.uk/data/assets/pdf˙file/0010/157879/003227.pdf. Royal College of Nursing; 2008.

RCPCH. Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Bridging the gaps: health care for adolescents. Available from: http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/sites/default/files/bridgingthegaps.pdf. London: RCPCH; 2003.

RCPE. Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Transition Steering Group. Think transition: develo** the essential link between paediatric and adult care. Available from: http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/clinical-standards/documents/transition.pdf. Edinburgh: Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh; 2008.

Lotstein DS, McPherson M, Strickland B, Newacheck PW. Transition planning for youth with special health care needs: results from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1562–8.

Scal P, Ireland M. Addressing transition to adult health care for adolescents with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1607–12.

Haffner D, Emma F, Eastwood DM, Duplan MB, Bacchetta J, Schnabel D, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of X-linked hypophosphataemia. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019;15(7):435–55.

McPherson M, Weissman G, Strickland BB, Van Dyck PC, Blumberg SJ, Newacheck PW. Implementing community-based systems of services for children and youths with special health care needs: How well are we doing? Pediatrics. 2004;113:1538–44.

Giannini S, Bianchi ML, Rendina D, Massoletti P, Lazzerini D, Brandi ML. Burden of disease and clinical targets in adult patients with X-linked hypophosphatemia. A comprehensive review. Osteoporos Int. 2021;32(10):1937–49.

Laurent MR, De Schepper J, Trouet D, Godefroid N, Boros E, Heinrichs C, et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and management of X-linked hypophosphatemia in Belgium. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;19(12):641543.

Bacchetta J, Rothenbuhler A, Gueorguieva I, Kamenicky P, Salles JP, Briot K, et al. X-linked hypophosphatemia and burosumab: practical clinical points from the French experience. Joint Bone Spine. 2021;88(5):105208.

Al Juraibah F, Al Amiri E, Al Dubayee M, Al Jubeh J, Al Kandari H, Al Sagheir A, et al. Diagnosis and management of X-linked hypophosphatemia in children and adolescent in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. Arch Osteoporos. 2021;16(1):52.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement.

Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet e-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34.

Moons P, Hilderson D, Van Deyk K. Congenital cardiovascular nursing: preparing for the next decade. Cardiol Young. 2009;19(Suppl 2):106–11.

Nakhla M, Daneman D, To T, Paradis G, Guttmann A. Transition to adult care for youths with diabetes mellitus: findings from a Universal Health Care System. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):e1134–41.

Adam V, St-Pierre Y, Fautrel B, Clarke AE, Duffy CM, Penrod JR. What is the impact of adolescent arthritis and rheumatism? Evidence from a national sample of Canadians. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:354–61.

Latzman RD, Majumdar S, Bigelow C, Elkin TD, Smith MG, Megason GC, et al. Transitioning to adult care among adolescents with sickle cell disease: a transitioning clinic based on patient and caregiver concerns and needs. Int J Child Health Adolesc Health. 2011;3(4):537–45.

Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Develo** a programme of transitional care for adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a postal survey. Rheumatology. 2004;43(2):211–9.

Shaw KL, Southwood TR, McDonagh JE. Transitional care for adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a Delphi study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:1000–6.

Clemente D, León L, Foster H, Carmona L, Minden K. Transitional care for rheumatic conditions in Europe: current clinical practice and available resources. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2017;15:49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s1269-017-0179-8.

Willis ER, McDonagh JE. Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services (NICE Guideline NG43). Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2018;103(5):253–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313208.

Pérez-López J, Cebeiro-Hualde L, García Morillo JS, Grau-Junyent JM, Hermida Ameijeiras A, López-Rodríguez M, et al. Proceso de transición de la asistencia pediátrica a la adulta en pacientes con errores congénitos del metabolismo. Documento de consenso. Med Clin (Barc). 2016;147:506.e1-506.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2016.09.018.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Academy of Family Physicians, and American College of Physicians, Transitions Clinical report Authoring Group. Clinical report-Supporting the Health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics. 2011;128:182–200. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-0969.

Geenen SJ, Powers LE, Sells W. Understanding the role of health care providers during the transition of adolescents with disabilities and special health care needs. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32:225–33.

Tuchman LK, Slap GB, Britto MT. Transition to adult care: experiences and expectations of adolescents with a chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:557–63.

McDonagh JE, Kaufman M. The challenging adolescence. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:872–5.

Reiss JG, Gibson RW, Walker LR. Health care transition: youth, family, and provider perspectives. Pediatrics. 2005;115:112–20.

Zhang LF, Ho JS, Kennedy SE. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of transition readiness assessment tools in adolescents with chronic disease. BMC Pediatr. 2014;9(14):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-4.

Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, White M, Gill N, Colbourne G, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2014;26(2):159–74. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2013-0512.

While A, Forbes A, Ullman R, Lewis S, Mathes L, Griffiths P. Good practices that address continuity during transition from child to adult care: synthesis of the evidence. Child Care Health Dev. 2004;30:439–52.

Ariceta G, Camacho JA, Fernández-Obispo M, Fernández-Polo A, Gámez J, García-Villoria J, et al. A coordinated transition model for patients with cystinosis: from pediatrics to adult care. Nefrologia. 2016;36(6):616–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nefro.2016.05.012.

Chabrol B, Jacquin P, Francois L, Broué P, Dobbelaere D, Douillard C, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in adolescents with hereditary metabolic diseases: specific guidelines from the French network for rare inherited metabolic diseases (G2M). Arch Pediatr. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2018.05.009.

Stepien KM, Kieć-Wilk B, Lampe C, Tangeraas T, Cefalo G, Belmatoug N, et al. Challenges in transition from childhood to adulthood care in rare metabolic diseases: results from the first multi-center European survey. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:652358. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.652358.

Jiang I, Major G, Singh-Grewal D, Teng C, Kelly A, Niddrie F, et al. Patient and parent perspectives on transition from paediatric to adult healthcare in rheumatic diseases: an interview study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e039670. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039670.

Lemke M, Kappel R, McCarter R, D’Angelo L, Tuchman LK. Perceptions of health care transition care coordination in patients with chronic illness. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173168. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3168.

Peter NG, Forke CM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF. Transition from pediatric to adult care: internists’ perspectives. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):417–23.

McDonagh JE, Farre A. Transitional care in rheumatology: a review of the literature from the past 5 years. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2019;21:57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-019-0855-4.

McDonagh JE, Shaw KL, Southwood TR. Growing up and moving on in rheumatology: development and preliminary evaluation of a transitional care programme for a multicentre cohort of adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Child Health Care. 2006;10:22–42.

McDonagh JE, Southwood TR, Shaw KL. The impact of a coordinated transitional care programme on adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:161–8.

Tucker LB, Cabral DA. Transition of the adolescent patient with rheumatic disease: issues to consider. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2005;52:641–52.

Rettig P, Athreya BH. Adolescents with chronic disease. Transition to adult health care. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4:174–80.

Acknowledgements

The collaboration of the scientific societies that endorsed the project is gratefully acknowledged: AECOM (Spanish Association for the Study of Inborn Errors of Metabolism), AENP (Spanish Association of Paediatric Nephrology), SEEN (Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition), SEEP (Spanish Society of Paediatric Endocrinology), SEIOMM (Spanish Society of Bone and Mineral Metabolism Research), SEMI (Spanish Society of Internal Medicine), SEN (Spanish Society of Nephrology) and SERPE (Spanish Society of Paediatric Rheumatology).

We would like to thank the following specialists for their participation: TEAM study group (alphabetical order):

Pilar Aguado Acín; María Teresa Alarcón Alacio; Cristina Alfaro Iznaola; María Rosa Alhambra Expósito; Rosa Arboiro Pinel; Francisco Arrieta Blanco; Verónica Ávila Rubio; Mª Pilar Bahíllo Curieses; Amaya Belanger-Quintana ; María del Pilar Bernabeu Gonzalvez; Cristina Julia Blázquez Gómez; Jordi Bosch Muñoz; Beatriz Bravo Mancheño; Yolanda Calzada Baños; Jorge Cancio Fanlo; Atilano Carcavilla Urquí; Marta Cecilia Carrasco Hidalgo-Barquero; Ana Castellano Martinez; Mar Espino Hernández; Laura Espinosa Román; Nuria Espinosa Segui; Angustias Fernandez Escribano; Mónica Furlano ; Leonor García Maset; Araceli García Pose; Ana María García Prieto; Mª Amelia Gómez Llorente; Yussel González Galván; Juan David González Rodríguez; Gema Grau Bolado; Julio Hernández Jaras; M. Alba Herreros Garcia; Emilia Hidalgo-Barquero del Rosal; Miguel Hueso Val; Elvira Izquierdo García; Marta Jiménez Moreno; Pedro López Mondéjar; Luis Carlos López Romero; María Isabel Luis Yanes; Javier Lumbreras Fernández; Alvaro Madrid Aris; Berta Magallares López; Maria Concepción Mir Perelló; Manuel Muñoz Torres; Francisco Antonio Nieto Vega; Carmen Ordas Calvo; Flor Angel Ordóñez Álvarez; Manel Perelló Carrascosa; Maria Vanessa Perez Gomez; Alvaro Perez Gomez; Pilar Peris Bernal; María Piedra León; Agustin Pijierro Amador; Francisco Pita Gutiérrez; Pablo Prieto Matos; Adriana Puente Garcia; M. C. Lourdes Rey Cordo; Jose A Riancho Moral; Isolina Riaño Galán; Nicolas Roberto Robles Pérez-Monteoliva; Diana Rodríguez Espinosa; Minerva Rodríguez García; Virginia Roldán Cano; Yolanda Romero Salas; Felipe Rubio Rodríguez; Judith Sánchez Manubens; Rosario Sánchez Martínez; Jaime Sanchez Del Pozo; Lucia Sentchordi Montané; Oscar Torregrosa Suau; Vicenç Torrente Segarra; Elena Urbaneja Rodríguez; Esther Valero Tena; Carmen Vicente Calderón; Ana Weruaga Rey; Andrea Zacarias Crovato.

Funding

This study was sponsored by KYOWA KIRIN FARMACÉUTICA, S.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC, CGA, GPM, RBT, ACBB. JVT, JJBM, PAS, SCB, YOI and BSL contributed to the design, data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. EC, CGA, GPM, RBT, ACBB. JVT, JJBM, PAS, SCB, YOI and BSL approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Medicinal Products of Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí of Sabadell, Spain (28-July-2020; Reference 2020/695). The study was guided by the basic ethical principles contained in the Declaration of Helsinki in its most recent version where it was applicable, and was completed following the international guidelines of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE) Good Epidemiology Practices and applicable national and European standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable to this study.

Competing interests

Yoko Olmedilla is an employee of Kyowa Kirin Farmaceutica, S.L. Begoña Soler was engaged to carry out the design, monitoring, statistical analysis and management of any publications derived from the study. Guillem Pintos received fees from Kyowa Kirin Farmacéutica, S.L. for coordination of the study, for consulting and as a speaker. José Jesús Broseta received fees for presentations and consulting from Kyowa Kirin. The other authors received fees from Kyowa Kirin Farmaceutica, S.L. for coordination of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Questionnaire for specialist consensus. Questionnaire used for specialist consensus.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Casado, E., Gómez-Alonso, C., Pintos-Morell, G. et al. Transition of patients with metabolic bone disease from paediatric to adult healthcare services: current situation and proposals for improvement. Orphanet J Rare Dis 18, 245 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02856-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-023-02856-6