Abstract

Background

Age-related dysbiosis of the microbiota has been linked to various negative health outcomes. This study aims to investigate the effects of a newly discovered dietary fiber compound (DFC) on aging, intestinal microbiota, and related metabolic processes. The DFC was identified through in vitro fermentation screening experiments, and its dosage and composition were determined based on a longevity dietary pattern.

Methods

Aged SPF C57BL/6 J mice (65 weeks old) and young mice (8 weeks old) were divided into three groups: a subgroup without dietary fiber (NDF), a low DFC dose subgroup (LDF, 10% DFC), and a high DFC dose subgroup (HDF, 20% DFC). The total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) activity, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity in liver and serum samples of the mice were measured according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The expression levels of characteristic bacterial genera and fecal metabolite concentrations in mice were determined using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and nuclear magnetic resonance hydrogen spectroscopy (1H NMR). Metabolomics analysis was further conducted to identify biological functions and potential pathways related to aging.

Results

After an 8-weeks dietary intervention, DFC supplementation significantly attenuated age-related weight loss, organ degeneration, and oxidative stress. And promoted the growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and inhibited the growth of Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Bacteroides (p < 0.05) in the intestinal tracts of aged mice. Metabolomic analysis identified glycolipid and amino acid metabolic pathway biomarkers associated with aging that were differentially regulated by DFC consumption. Correlation analysis between the identified microbial flora and the biomarkers revealed potential mechanistic links between altered microbial composition and metabolic activity with aging markers.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study revealed an important mechanism by which DFC consumption impacts healthspan and longevity, shedding light on optimizing dietary fiber or develo** fiber-based interventions to improve human health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bama County in Guangxi is a world-renowned longevity town, where the phenomenon of longevity is highlighted [1]. Our research team conducted a lot of research on the dietary characteristics of the longevity population in the early stage, and found that the traditional diet in the Bama area is mainly based on the food intake of plant foods, such as coarse grains (Taro, hemp, corn, cassava, etc.), vegetables (Pumpkin seedlings, sweet potato leaves, water spinach, amaranth, wild rattan, etc.), and fruits (Kumquat, plantain, etc.) and the intake of dietary fiber is relatively high [2, 3], and dietary fiber is closely linked to the formation of longevity phenomenon, and longevity is closely related to the structure of the intestinal microenvironment or intestinal flora [4]. A specific bacterial community pattern and signature taxa of long-lived people were found in long-lived families, such as the enrichment of Enterobacteriaceae in all age groups and the higher abundances of Christensenellaceae, Verrucomicrobiaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, Rikenellaceae, Mogibacteriaceae, and Odoribacteraceae in long-lived elderly [4]. Therefore, exploring the relationship between dietary fiber and aging, intestinal microenvironment, or intestinal flora is of great significance to longevity research. Our team has summarized the dietary pattern reflecting the dietary characteristics of the longevity population and found that this pattern has good anti-aging effects and development potential [5, 6], but the extent to which dietary fiber plays a role in it has not been studied.

Age-related dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, characterized by reduced diversity and altered composition, has been linked to age-related metabolic dysregulation and increased risk for various chronic diseases [7]. Dietary fiber intake is known to benefit gut microbiota and metabolic homeostasis, but the impacts of specific fiber types and combinations on microbiota-related biomarkers of aging are not fully understood [8]. Elucidating the mechanisms by which dietary fiber compounds modulate the gut microbiome and related metabolic changes is of great interest for advancing longevity research. Previous studies have examined the effects of individual dietary fibers or simple combinations on health outcomes. Dietary fiber intake has been shown to lower blood sugar and cholesterol [2: Table S1. Mice (female and male) were raised separately, with 6 in each cage. They were raised under light/dark cycling conditions of 24 ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 55 ± 5%, and 12 h, and were able to freely obtain food and water. Before the dietary intervention, all mice received a libitum diet and water for 1 week. After this acclimatization, the 8-week intervention was initiated. At the intervention end, mice were fasted and dehydrated for 12 h. Following anesthesia, heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, cecum contents, and colon contents were collected and stored in a − 80 °C.

Measurement of body weight and food intake of mice

Fecal samples were collected at week 1 and week 8 by massaging the abdomen. Body weight and food intake were recorded weekly. Fecal samples were stored in a refrigerator at − 80 °C until analysis. Before weighing, mice were fasted for 12 h.

Determination of organ coefficient in mice

The weight of each part of the organs of the mice was weighed and calculated according to the following formula:

m1 is the weight of the organ and m2 is the final body weight of the mouse.

Determination of mouse liver and serum antioxidant capacity

Total antioxidant (T-AOC) capacity, total superoxide dismutase (T-SOD) activity, malondialdehyde (MDA) content, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity were determined in mouse liver and serum samples according to the manufacturer's protocols (Nan**g Jiancheng Institute of Bioengineered Enzymes, Nan**g, China).

Extraction of DNA from mouse feces

Bacterial DNA was extracted from fecal samples using a fecal genomic DNA extraction kit (Solarbio, Bei**g, China). Nucleic acids were obtained from 200 mg of fecal samples and eluted in 90 µL of elution buffer. DNA concentration was quantified using an infinite M200 pro microtiter detector (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland). Extracted DNA samples were stored at − 80 °C until further analysis.

Determination of qPCR

Fecal DNA samples were quantified by qPCR using a Roche Light Cycler 96 qPCR instrument (Roche Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) with 96-well optical plates. Primers used are listed in Table 1. Relative quantification was performed using the comparative Ct method, and the formula is as follows:

Determination of metabolites in mouse feces by 1H NMR

A homogenized 50 mg aliquot was placed into a 2.0 mL safe-lock tube (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Then, 500 μL PBS/D2O buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) was added, containing 10% D2O (v/v) and 0.005% TSP (w/v). The mixture was repeatedly frozen and thawed in liquid nitrogen three times, homogenized for 60 s, and then centrifuged (12,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C). Collect the supernatant and repeat the extraction process. The pooled supernatants were collected and centrifuged (12,000 g, 15 min, 4 °C) and 550 μL was transferred to a 5 mm NMR tube for detection.

1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker Avance 500 MHz NMR spectrometer at 298 K using a water pre-saturated standard one-dimensional NOESYPR 1D pulse sequence (recycle delay − 90° − t1 − 90° − tm − 90°—acquisition) with water suppression. Acquisition parameters were relaxation delay 2.0 s, mixing time 0.1 s, 64 scans, 65,536 data points, spectral width 10,000 Hz. Free induction decays were multiplied by 0.5 Hz exponential line broadening before Fourier transformation. Spectra were referenced to TSP (δ = 0.0 ppm), phase and baseline corrected and integrated over the spectral regions of 0.00–9.00 ppm into 0.001 ppm bins. The water region (4.70–5.10 ppm) was excluded data normalized before analysis.

Metabolomics analysis

Multivariate analysis of NMR data was performed using the metaboanalyst website (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/). Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) was used to examine any intrinsic clustering. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was done in SIMCA 14.1 (Umetrics, Sweden) software to maximize the separation of fecal metabolites between groups after DFC intervention. OPLS-DA models were validated by 200 conditions using the permutation tests. Metabolic pathway enrichment and pathway analysis using the kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) database identified altered pathways based on differential metabolites. Correlation heatmaps and network analysis were generated in the omicstudio website (https://www.omicstudio.cn/tool) to determine associations between the characterized microbiota and metabolites.

Statistical analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for multiple comparisons. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

DFC prevents age-related weight loss and enhances food utilization

Age-related loss of muscle mass contributes significantly to frailty and mortality risk. We therefore firstly tested whether DFC could attenuate weight loss in aged mice with 8 weeks of dietary intervention. There was no significant change in body weight for either YG or AG groups in the first week following DFC intervention (p > 0.05) (Table 2). However, by week 8, the AG-NDF group showed decreased body weight compared to baseline (− 1.60 ± 1.56 g, p < 0.05), indicating age-related weight loss. In contrast, DFC supplementation attenuated this weight loss in a dose-dependent manner, with both AG-LDF (+ 3.10 ± 2.45 g, p < 0.05) and AG-HDF (+ 5.30 ± 2.04 g, p < 0.05) groups showing significantly increased body weight compared to AG-NDF controls. The body weight gains in AG-HDF mice were also significantly higher compared to AG-LDF (p < 0.05).

In young control mice (YG groups), DFC decreased body weight gain relative to YG-NDF controls, with enhancement more pronounced in YG-HDF (− 2.20 ± 1.84 g) versus YG-LDF (− 3.60 ± 2.38 g) groups (p < 0.05). Food intake followed a similar improvement with DFC in both aged and young groups (Fig. 1A, B), indicating food utilization efficiency was increased with DFC supplementation, particularly at higher doses. Overall, these data demonstrate that DFC attenuates age-associated weight loss and improves food utilization in mice.

The impacts of DFC on organ coefficients in aged versus young mice

To assess changes in relative organ mass, organ coefficients (the ratio of organ weight to overall body weight) were determined.. The values of organ coefficients of mice after 8 weeks of DFC intervention were calculated and are shown in Table 3. Compared to YG-NDF controls, the organ coefficients of all examined organs were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in AG-NDF mice. In the YG group, compared with the YG-NDF controls, the liver coefficient decreased significantly in the low-dose and high-dose DFC groups (p < 0.05), but there were no significant changes in other organ coefficients (p > 0.05). In the AG groups, heart, liver, spleen, and lung coefficients exhibited significant increases (p < 0.05) with both low and high-dose DFC versus AG-NDF controls. Kidney coefficients did not significantly differ between any AG subgroups (p > 0.05). These results demonstrate that organ decline occurred in aged mice to a certain extent, and DFC supplementation could increase the organ coefficient of aged mice, and the organ-protective effect of DFC appear somewhat more pronounced in higher doses of AG mice.

Effects of DFC on antioxidant capacity in aged versus young mouse

As oxidative stress plays a key role in the aging process, we hypothesized that DFC intervention might help suppress oxidative stress through increasing antioxidant capacity. Therefore, we examined the effects of DFC on antioxidant capacity in the livers and serum of young versus aged mice by measuring total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC), superoxide dismutase (T-SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) that reflect antioxidant capacity, as well as malondialdehyde (MDA), a biomarker of oxidative stress (Fig. 2) [22, 23].

Compared to YG-NDF controls, T-AOC activities significantly increased in both the liver (76.51%) and serum (45.10%) of YG-HDF mice (p < 0.01). T-SOD activity also increased by 44.91% in YG-HDF serum (p < 0.01). MDA decreased by 77.90% in YG-HDF liver (p < 0.01). Liver GSH-Px increased by 63.26% in YG-HDF (p < 0.01). In AG mice, liver and serum T-AOC showed large significant increases of 95.64% and 115.05% in AG-HDF, respectively (p < 0.01). Liver T-SOD increased by 8.71% in AG-HDF (p < 0.05). Serum T-SOD increased by 77.55% in the AG-HDF (p < 0.01). MDA decreased by 70.76% in AG-HDF liver (p < 0.01) and 12.00% in serum (p < 0.05). Liver GSH-Px activity increased by 60.58% with AG-HDF (p < 0.01), but serum GSH-Px activity had no significant difference (p > 0.05). Collectively, DFC supplementation substantially improved antioxidant capacity in both young and aged mice, especially at high doses. The liver and serum of aged mice showed greater enhancements in T-AOC with DFC compared to young controls.

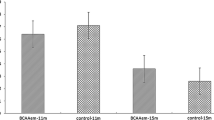

DFC supplementation shifted Characteristic bacterial genera composition

As the gut microbiota plays an important role in health and can be impacted by diet and age, we evaluated the effects of 8 weeks of DFC supplementation on key gut bacterial groups in feces of YG and AG mice (Fig. 3). As we all know, when the amount of E. coli in the intestine is excessive, it will destroy the intestinal barrier and become an opportunistic pathogen [24]. Compared to NDF controls, the E. coli decreased with DFC treatment in both YG and AG groups. In AG mice, E. coli was significantly reduced by 20.84% in the LDF group (p < 0.05) and 45.62% in the HDF group (p < 0.01). In YG mice, it was significantly reduced by 38.66% (p < 0.05) in the LDF group and 63.64% (p < 0.01) in the HDF group. In the contrary, the beneficial genus Lactobacillus was significantly elevated by 128.46% (p < 0.01) in the YG-LDF group and 449.74% (p < 0.01) in the YG-HDF group. It was elevated in the AG groups as well by 79.31% (p < 0.05) in the AG-LDF group and 329.73% (p < 0.01) in the AG-HDF group. Another beneficial gut microbe Bifidobacteria was also elevated in both YG and AG groups upon DFC intervention, which was elevated by 109.05% (p < 0.05) in the YG-LDF group, 341.79% (p < 0.01) in the YG-HDF group, 66.34% (p < 0.05) in the AG-LDF group and 239.75% (p < 0.01) in the AG-HDF group. While being generally considered a beneficial genus of gut bacteria, however, the level of Bacteroides was significantly reduced by 39.22% (p < 0.01) in the YG-LDF group, 45.62% (p < 0.01) in the YG-HDF group, 52.00% (p < 0.05) in the AG-LDF group and 63.42% (p < 0.01) in the AG-HDF. It is known that some species of Bacteroides can become opportunistic pathogens if they spread beyond the gut and cause systemic infection [25]. Therefore, these results indicate that DFC supplementation, significantly increased beneficial bacteria and reduced potential pathogens in both young and aged mice, suggesting DFC may improve characteristic bacterial genera composition in aging.

DFC supplementation alters characteristic bacterial genera composition in young and aged mice. Relative abundance of key gut bacterial genera was determined in the feces of young (YG) and aged (AG) mice after 8 weeks of DFC supplementation. (A) E. coli. (B) Lactobacillus. (C) Bifidobacterium (D) Bacteroides. Data shown as median and SD relative to respective NDF groups, analyzed by Student T-test. Note *P < 0.05 **P < 0.01 vs NDF group

Identification of metabolite changes in mouse feces upon DFC intervention

To investigate the metabolic alterations induced by DFC supplementation, we performed untargeted 1H NMR-based metabolomics analysis on fecal samples from mice after 8 weeks of DFC treatment. A representative metabolite 1H NMR spectrum in feces was shown in Fig. 4. A total of 46 metabolites were identified in mouse fecal samples, with chemical shifts mainly distributed in the range of 0.5–8.5 ppm, spanning diverse chemical classes including sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, organic acids, and others. Assignment of metabolites was confirmed using the human metabolome database (HMDB) (http://www.hmdb.ca/) and biological magnetic resonance bank (BMRB) (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu/), which were calibrated and assigned in conjunction with references [26,27,28], and are summarized in Additional file 3: Table S1. The 1H signal in the 0.8–3.0 ppm region represents amino acids (leucine, valine, alanine, aspartic acid, proline, and lysine, etc.), short chain fatty acids (acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid, etc.), organic carboxylic acids (bile acid, lactic acid, succinic acid, and citric acid, etc.), and other metabolites (dimethylamine, trimethylamine, and N-acetylglycoprotein, etc.). The 1H peak in the 3.0–5.5 ppm range mainly includes sugars (α-Glucose, β-Glucose, α-Galactose, and β-Galactose), amino acids (such as histidine, lysine, threonine, glycine, and serine), and other metabolites (such as choline and methanol). Finally, amino acids (tyrosine), organic acids (formic acid, fumarate), and other metabolites (inosine, uric acid, uracil, xanthine, and hypoxanthine, etc.) were found in the region of around 5.5–8.5 ppm.

To characterize the overall metabolic profile in the feces of each mouse group, PCA was performed on the 1H NMR spectral data. As shown in Fig. 5, The PCA scores plot showed clustering of the samples according to the treatment group, with separation along the first principal component (PC1, 47%) distinguishing the young control, aging model, and DFC-treated aging groups. The second principal component (PC2, 11.6%) revealed the metabolic separation characteristics between the aging model group fed basal diet versus the low and high-dose DFC groups.

Scatter plot of PCA scores of fecal metabolites in mice after DFC intervention. PCA reveals dose-dependent and age-dependent changes in the fecal metabolomic profiles of mice in response to 8 weeks of dietary DFC intervention. Note AN = aging mice group on a no dietary fiber feed (aging control); AL = aging mice group on a low-dose DFC feed; AH = aging mice group on a high-dose DFC feed; YN = young mice group on a no dietary fiber feed group (negative control)

Altered fecal metabolites in mice following DFC intervention

While PCA demonstrated clear metabolic changes between different groups, there was some overlap in the PCA scores clusters. To better discriminate the metabolic variations between groups, OPLS-DA was applied. As shown in Additional file 3: Fig. S1, the R2Y and Q2 values were greater than 0.9 for all pair-wise comparisons between groups: R2Y = 0.994 and Q2 = 0.991 between the AG and YG group; R2Y = 0.994 and Q2 = 0.987 between the LDF and NDF group; R2Y = 0.994 and Q2 = 0.987 between the HDF and NDF group. When these values are greater than 0.5, it is considered a high degree of fitting. The closer the values to 1, the more reliable the OPLS-DA model. Therefore, the above results indicate the OPLS-DA models have excellent predictive ability and can effectively explain the significant differences in fecal metabolites among different mouse groups.

A permutation test was conducted under 200 conditions for further interactive validation, which confirmed the robustness of the OPLS-DA models (as shown in Additional file 3: Fig. S1). Based on the log2Fold Change (log2FC) value combined with variable importance in projection (VIP) > 1 and p < 0.05, differential metabolites and up-regulation ranges were identified (Table 4). Between AG and YG, 9 metabolites were altered including increased uric acid, threonine, inosine, fumarate, leucine, pyruvate, and aspartic acid, and decreased propionic acid and butyric acid in AG. Between LDF and NDF, 12 metabolites changed significantly with propionic acid, butyrate, proline, glutamate, serine, fumarate, and citric acid were elevated in LDF while uridylic acid, trimethylamine, threonine, aspartate, and inosine decreased. Finally, 11 metabolites differed between the HDF and NDF groups, with lactate, butyric acid, succinic acid, and propionic acid upregulated and uric acid, pyruvate, threonine, valine, β-glucose, alanine, and aspartic acid downregulated in HDF.

In summary, the OPLS-DA models identified distinct metabolite signatures differentiating the aging, DFC-treated, and young control groups, providing insight into the metabolic pathways altered by aging and DFC supplementation.

Metabolic pathway analysis of age-related changes and the impact of DFC intake on fecal metabolites

To gain further insights into the metabolic perturbations underlying the observed metabolite changes with DFC treatment and aging, metabolic pathway analysis was performed on potential differential metabolites (Fig. 6). Between AG and YG, the altered metabolites were enriched in pyruvate metabolism and alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism pathways. Between LDF and NDF, 5 pathways were significantly affected including alanine, aspartic acid and glutamate metabolism, arginine biosynthesis, tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), arginine, and proline metabolism, as well as D-glutamine and D-glutamate metabolic pathways. Between HDF and NDF, enriched pathways included pyruvate metabolism, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism. The common enriched pathways across the comparisons highlight dysregulation of energy metabolism (TCA cycle, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis) as well as amino acid metabolism mediated by the microbiome (alanine, aspartate, glutamate pathways) with DFC treatment and aging. Specifically, the TCA cycle and glycolysis pathways suggest modulation of carbohydrate metabolism and cellular respiration. Changes in amino acid pathways indicate altered microbial fermentation and inter-conversion of amino acids. Taken together, the metabolic pathway analysis points to significant effects of DFC and aging on gut microbial activity related to carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism.

Effect of DFC intake on key metabolic pathways altered in fecal metabolites of mice groups. A Metabolic pathways of differential metabolites between AG and YG groups. B Metabolic pathways of differential metabolites between LDF and NDF groups (C) Metabolic pathways of differential metabolites between HDF and NDF groups. Each bubble represents a distinct metabolic pathway. The Bubble color indicates the P-value, and the horizontal axis represents the enrichment factor. Note The larger the enrichment factor, the smaller the P-value, and the more significant the enrichment degree. Altered metabolic pathways were identified by screening for those with P < 0.05 and enrichment factors > 0.1

Correlation between characteristic bacterial genera and major differential fecal metabolites

To further elucidate the interactions between the characteristic bacterial genera and main differential metabolites, Spearman correlation heatmap and correlation network analysis were performed between the characteristic bacterial genera and the main differential metabolites in each intervention group (Fig. 7).

Spearman correlation analysis between characteristic fecal microbiota and main differential metabolites. A Heatmap and network diagram showing correlations for the LDF group. B Heatmap and correlation network diagram showing correlations for the HDF group. The heatmaps display the Spearman correlation coefficient (R) values, with red indicating a positive correlation and blue indicating a negative correlation. Note The network diagrams visualize the correlations, with green lines representing positive correlation, gray lines representing negative correlations, and line thickness proportional to the correlation coefficient. Red circles denote bacteria genera and blue rectangles denote metabolites

In the LDF group, E. coli was positively correlated with inosine and negatively correlated with glutamate. Lactobacillus displayed positive correlations with propionic acid and butyric acid, and negative correlations with aspartic acid, inosine, trimethylamine, and uric acid. Bifidobacterium was positively associated with propionic acid and butyric acid, and negatively related to uric acid and trimethylamine.

In the HDF group, E. coli showed negative correlations with butyric acid, lactic acid, and propionic acid, and was also negatively correlated with alanine. Lactobacillus displayed positive correlations with butyric acid, lactic acid, and propionic acid, while showing negative correlations with threonine, alanine, and aspartic acid. Bifidobacterium was positively correlated with butyric acid, lactic acid, and propionic acid, and negatively correlated with alanine. Bacteroides exhibited positive correlations with β-glucose and pyruvate.

These association patterns suggest the increased Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium with HDF may drive elevations in short-chain fatty acids through carbohydrate fermentation. The decreased E. coli may relieve some of the reductions seen in metabolites like alanine. The higher Bacteroides could contribute to increases in lactate, pyruvate, and glucose.

Discussion

This study utilized a natural aging mouse model to elucidate the regulatory effects of DFC on aging indicators, characteristic bacterial genera, and metabolites. The results demonstrate DFC can delay age-related declines in weight, organ function, and oxidative stress. DFC also promoted the growth of beneficial Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species while inhibiting harmful E. coli bacteria. Metabolomics analysis revealed DFC reduces age-associated metabolic dysregulation of carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids. Correlation analysis explored links between altered metabolites and microbial community changes. Overall, the longevity diet pattern mediated by DFC showed positive regulatory effects on characteristic bacterial genera and metabolites in aging mice, shedding insights into how dietary fiber- characteristic bacterial genera -metabolite interactions impact host health during aging.

Weight is an important indicator of overall health status. Previous studies have shown that mice experience significant memory loss and weight loss decline along with ageing [29]. Yu [24] found that mice fed a standard diet lost significant weight during aging, while mice fed a dietary fiber complex (CDFC) inhibited aging-induced weight loss. In this study, we found the aging control group (AG-NDF) showed a weight loss of 1.60 ± 1.56 g compared to baseline while aging mice fed DFC had reversed the weight loss caused by aging. The high-dose DFC group demonstrated the most substantial effect, indicating DFC alleviated age-related weight loss to maintain health.

Organ coefficient is an important index to evaluate the growth, development, and physiological function of mice. Previous studies have shown that the aging process is characterized by changes in appearance, including a significant decrease in organ coefficients [30]. Here, aging control mice showed reduced organ coefficients, reflecting degeneration. However, 8 weeks of DFC supplementation significantly improved organ coefficients, demonstrating that DFC intake alleviated the rate of organ decline in aging mice.

Antioxidant capacity is an important marker of aging and overall health status. In this study, DFC supplementation did not significantly alter individual antioxidant markers in aging mice. However, overall, there were upward trends in T-AOC, T-SOD, and GSH-Px activities alongside a downward trend in MDA. This suggests DFC may alleviate oxidative stress to some degree, thereby improving overall health levels. DFC's effects on oxidative stress and longevity may be attributable to polyphenols, which are important antioxidants rich in dietary fibers [31, 32]. Our results provide initial evidence that DFC supplementation may mitigate age-related oxidative stress, which is consistent with previous studies. Soluble dietary fiber from passion fruit peel was shown that can prevent oxidative stress induced by DSS in the mouse colon by regulating GSH-Px levels and SOD activity [33]. Similarly, tea residue fiber was reported that increased the levels of SOD and GSH-Px and reduced MDA in diabetes rats [9].

The major impact of DFC supplementation on longevity might be due to a positive regulatory effect on the characteristic bacterial genera. Previous studies have shown dietary fibers can selectively enrich beneficial bacteria. For example, a dietary fiber composite (oat corn konjac, oat bran, skimmed milk, whole kudzu root, pumpkin) selectively enriched beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia, and Rombutzia in obese mice [34]. Chitosan promoted the growth of the Lactobacillus genus while inhibiting the Enterobacterium and Enterococcus [35]. Stachyose α-Oligosaccharides also increased beneficial Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium and inhibited the growth of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae [36]. Similarly, our study showed that 8 weeks of DFC intake increased beneficial Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium genera in aging mice by 329.73% and 239.75% respectively, while decreasing the harmful bacteria E. coli by 45.62%, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium are considered the most typical probiotics [37], producing short chain fatty acids such as acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid to promote intestinal health [38, 39]. In summary, DFC supplementation significantly promoted the growth of advantageous bacteria (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium) in the intestine of aging mice, while suppressing undesirable bacteria (E. coli) and Bacteroides.

The mechanisms by which the DFC intake improved intestinal health and longevity are closely correlated to alterations of metabolic pathways. Compared to young mice, aging mice showed upregulation of seven differential metabolites including uric acid, aspartic acid, threonine, inosine, pyruvate, and fumarate, while downregulation of propionic acid and butyric acid. They are metabolites relating to glycolysis downstream of pyruvate, players involved in the TCA cycle, and lipid and amino acid metabolism pathways. These changes indicated that aging mice may experience dysregulation of energy production, lipid metabolism disorders, and inflammatory reactions. Our study indicated that DFC supplementation could effectively reverse most of the above metabolic changes, demonstrating significant effects on microbial carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism related to aging and gut health.

DFC-induced metabolic changes appear to counteract some of the age-associated disruptions in microbial community function. For example, the upregulation of uric acid and increased fecal short-chain fatty acids like propionic acid and butyric acid are known to be related to the growth of certain intestinal bacteria, which are consistent with previous studies [40, 41]. Pathway analysis further supports DFC modulation of key metabolic processes. As summarized in Fig. 8, alanine, aspartic acid, and glutamate generate pyruvate and fumarate, participating in the TCA cycle to generate energy. Dysregulated glycolysis and glutathione metabolism can lead to lipid accumulation and oxidative stress that contribute to aging [42,43,44,45]. After DFC intervention, the levels of trimethylamine, valine, threonine, and inosine were down regulated, while the levels of fumarate and citric acid were upregulated. Decreased threonine and inosine levels suggest DFC may reduce risks of inflammatory conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBD) and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) [26, 27]. The reduction in valine levels means that DFC may be associated with a reduced risk of diabetes [46]. As trimethylamine is considered a risk marker for cardiovascular disease [47], DFC intervention appears to improve cardiovascular health as well.

Summary of metabolic pathways of the DFC involved in glucose lipid metabolism and amino acid metabolism. Pyruvate and glycolysis/glycolysis pathways are the main pathways regulating glucose metabolism and energy metabolism, and the lactate produced by this pathway can be converted to other short-chain fatty acids such as propionic acid and butyric acid. The alanine, aspartate, and glutamate pathways produce pyruvate and gibberellic acid, respectively, which participate in the citric acid cycle for energy production, with gibberellic acid, citric acid, and succinic acid being intermediates of the TCA cycle. Note Red = upregulated metabolites; Blue = downregulated metabolites

In summary, DFC-induced alterations in TCA cycle intermediates, lipid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism likely counteract age-related metabolic dysfunction, which is mediated through modulation of the microbiome. The complex in vivo metabolic impacts of DFC underscore the intricate interplay between diet, microbiome, and host.

Conclusion

Our multi-dimensional analysis shows DFC supplementation can favorably reshape microbial-host metabolic interactions during aging through specific pathways. The longevity diet pattern established here supplies a framework for optimizing dietary fiber content and composition to benefit the characteristic bacterial genera and host metabolism throughout life. Further research is warranted to build upon these findings and translate them into dietary recommendations and interventions that promote healthy aging in humans. However, this study only investigated the changes in four characteristic bacterial genera. Future research can determine the overall regulation of gut microbiota through high-throughput sequencing technology to further reveal the interaction between dietary fiber, gut microbiota, and host.

Availability of data and materials

The data in this study are available on request from the author.

References

Li H, Ren M, He Q, Gao J, Li Q. Revealing the longevity code of humans with up to extreme longevity in Guangxi based on physical examination indicators and personalized biomarkers of aging. Biomed Res Int. 2022;2022:2810379.

Cai D, Zhao S, Li D, Chang F, Tian X, Huang G, et al. Nutrient intake is associated with longevity characterization by metabolites and element profiles of healthy centenarians. Nutrients. 2016;8(9):564.

Han K, Ma J, Dou J, Hao D, Zhu W, Yu X, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of a dietary pattern on health metrics and fecal metabolites in volunteers with risk of cardiovascular disease. Front Nutr. 2022;9:853365.

Ren M, Li H, Fu Z, Li Q. Succession analysis of gut microbiota structure of participants from long-lived families in Hechi, Guangxi, China. Microorganisms. 2021;9(12):2524.

Huang Y, Mei L, Pan H, Qin L, Rao C, Nie M, et al. Anti-aging effect of bama longevity characteristic dietary patterns in naturally aging mice. Food Sci. 2021;42:137–44.

Song Q, Ai L, Lu H, Hao D, Chen Y, Sun H, et al. Effect of bama longevity dietary patterns on antioxidant stress in a mouse model of aging. Food Sci. 2018;39:147–53.

Crnčević N, Hukić M, Deumić S, Selimagić A, Dozić A, Gavrankapetanović I, et al. Gastrointestinal tract microbiome effect and role in disease development. Diseases. 2022;10(3):45.

Tran TTT, Cousin FJ, Lynch DB, Menon R, Brulc J, Brown JR, et al. Prebiotic supplementation in frail older people affects specific gut microbiota taxa but not global diversity. Microbiome. 2019;7(1):39.

Huang H, Chen J, Chen Y, **e J, Xue P, Ao T, et al. Metabolomics combined with 16S rRNA sequencing to elucidate the hypoglycemic effect of dietary fiber from tea residues. Food Res Int. 2022;155:111122.

Zhang S, Xu X, Cao X, Liu T. The structural characteristics of dietary fibers from Tremella fuciformis and their hypolipidemic effects in mice. Food Sci Human Wellness. 2023;12(02):503–11.

Bai X, He Y, Quan B, **a T, Zhang X, Wang Y, et al. Physicochemical properties, structure, and ameliorative effects of insoluble dietary fiber from tea on slow transit constipation. Food Chem. 2022;X14:100340.

Petra L, Michael S, Duncan SH, Walker AW, Indrani M. Dietary fibre complexity and its influence on functional groups of the human gut microbiota. Proc Nutr Soc. 2021;80(4):386–97.

Hua M, Fan M, Li Z, Sha J, Sun Y. Ginseng soluble dietary fiber can regulate the intestinal flora structure, promote colon health, affect appetite and glucolipid metabolism in rats. J Funct Foods. 2021;83(3209):104534.

Wang G, Zhong D, Liu H, Yang T, Zhang Y. Water soluble dietary fiber from walnut meal as a prebiotic in preventing metabolic syndrome. J Funct Foods. 2021;78:104358.

Cheng W, Lu J, Li B, Lin W, Zhang Z, Wei X, et al. Effect of functional oligosaccharides and ordinary dietary fiber on intestinal microbiota diversity. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1750.

Shi F, Zhou F, Zheng X, Lv J, Yu X, Zhou Y, et al. Effects of dietary fiber compounds on characteristic human flora and metabolites mediated by the longevity dietary pattern analyzed by in vitro fermentation. Nutrients. 2022;14(23):5037.

Cheng Y, Zuo HJ, Liao HY, Chen JY, Zhang TL, Pei XF, et al. Establishment of real-time PCR method for detection of intestinal bacteria. Mod Prev Med. 2014;41:4338–41.

Nelson EA, Palombo EA, Knowles SR. Comparison of methods for the extraction of bacterial DNA from human fecal samples for analysis by real-time PCR. Technol Educ Top Appl Microbiol Microb Biotechnol. 2010;2:1479–85.

Walter J, Hertel C, Tannock GW, Lis CM, Munro K, Hammes WP. Detection of Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Weissella species in human feces by using group-specific PCR primers and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(6):2578–85.

Rinttilä T, Kassinen A, Malinen E, Krogius L, Palva A. Development of an extensive set of 16S rDNA-targeted primers for quantification of pathogenic and indigenous bacteria in fecal samples by real-time PCR. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;97(6):1166–77.

Pang X, Ding D, Wei G, Zhang M, Wang L, Zhao L. Molecular profiling of Bacteroides spp in human feces by PCR-temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;61(3):413–7.

Mousavi SN, Faghihi A, Motaghinejad M, Shiasi M, Imanparast F, Amiri HL, et al. Zinc and selenium co-supplementation reduces some lipid peroxidation and angiogenesis markers in a rat model of NAFLD-fed high fat diet. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2018;181(2):288–95.

Ren Z, Li J, Song X, Zhang J, Wang W, Wang X, et al. The regulation of inflammation and oxidative status against lung injury of residue polysaccharides by Lentinula edodes. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;106:185–92.

Yu X, Liang X, Han K, Shi F, Meng N, Li Q. Anti-aging effect of dietary fiber compound mediated by Guangxi longevity dietary pattern on natural aging mice. Nutrients. 2022;14:3181.

Wexler AG, Goodman AL. An insider’s perspective: bacteroides as a window into the microbiome. Nat Microbiol. 2017;2:17026.

Carvalho DV, Silva LMA, Alves Filho EG, Santos FA, Lima RP, Viana AFSC, et al. Cashew apple fiber prevents high fat diet-induced obesity in mice: an NMR metabolomic evaluation. Food Funct. 2019;10(3):1671–83.

Shao T, He Z, **e Z, Li H, Wang M, Wen C. Characterization of ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis using 1H NMR-based metabolomics of human fecal extracts. Metabolomics. 2016;12:70.

Lee JS, Kim SY, Chun YS, Chun YJ, Shin SY, Choi CH, et al. Characteristics of fecal metabolic profiles in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with predominant diarrhea investigated using 1H-NMR coupled with multivariate statistical analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(6):e13830.

Sun C, Ying ZP. Dihydromyricetin improves cognitive impairments in D-galactose-induced aging mice through regulating oxidative stress, and inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2021;66:e2101002.

Chen P, Chen F, Zhou B. Antioxidative, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects of ellagic acid in liver and brain of rats treated by D-galactose. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1465.

Mézes M, Erdélyi M. Az élelmiszerek rosttartalmának antioxidáns hatása: antioxidant effect of the fibre content of foods. Orv Hetil. 2018;159(18):709–12.

Guo W, Shu Y, Yang X. Tea dietary fiber improves serum, and hepatic lipid profiles in mice fed a high cholesterol diet. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2016;71(2):145–50.

Bueno LR, da Silva Soley B, Abboud KY, França IW, da Silva KS, de Oliveira NMT, et al (2022) Protective effect of dietary polysaccharides from yellow passion fruit peel on DSS-induced colitis in mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 6298662

Huo R, Zhang M, Zhang Y, Bai X, Zhang Y, Guo X. Effects of oat complex high-fiber formula powder on the composition of intestinal microbiota and enzyme activities in mice induced by a high-fat diet. Front Nutr. 2022;9:871556.

Zhang D, **ng Y, Liu LK, Li XL. Prebiotic-like effects of chitosan on the intestinal microflora in mice. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2020;33(3):909–13.

Li T, Lu X, Yang X. Stachyose-enriched α-galacto-oligosaccharides regulate gut microbiota and relieve constipation in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(48):11825–31.

Rather SA, Pothuraju R, Sharma RK, De S, Mir NA, Jangra S. Anti-obesity effect of feeding probiotic dahi containing Lactobacillus casei NCDC 19 in high fat diet-induced obese mice. Int J Dairy Technol. 2015;67(4):504–9.

LeBlanc JG, Chain F, Martín R, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Courau S, Langella P. Beneficial effects on host energy metabolism of short-chain fatty acids and vitamins produced by commensal and probiotic bacteria. Microb Cell Fact. 2017;16(1):79.

Lu S, Williams BA, Flanagan BM, Yao H, Mikkelsen D, Gidley MJ. Fermentation outcomes of wheat cell wall related polysaccharides are driven by substrate effects as well as initial fecal inoculum. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;120(8):106978.

Whiteley HR. Fermentation of amino acids by Micrococcus aerogenes. J Bacteriol. 1957;74(3):324–30.

Nakajima H, Nakanishi N, Miyoshi T, Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Senmaru T, et al. Inulin reduces visceral adipose tissue mass and improves glucose tolerance through altering gut metabolites. Nutr Metab. 2022;19(1):50.

Bhatia H, Pattnaik BR, Datta M. Inhibition of mitochondrial β-oxidation by miR-107 promotes hepatic lipid accumulation and impairs glucose tolerance in vivo. Int J Obes. 2016;40(5):861–9.

Chen R, Wang J, Zhan R, Zhang L, Wang X. Fecal metabonomics combined with 16S rRNA gene sequencing to analyze the changes of gut microbiota in rats with kidney-yang deficiency syndrome and the intervention effect of You-gui pill. J Ethnopharmacol. 2019;244:112139.

Zhang C, Dong L, Wu J, Qiao S, Xu W, Ma S, Zhao B, Wang X. Intervention of resistant starch 3 on type 2 diabetes mellitus and its mechanism based on urine metabolomics by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;128:110350.

Zheng L, Cardaci S, Jerby L, MacKenzie ED, Sciacovelli M, Johnson TI, et al. Fumarate induces redox-dependent senescence by modifying glutathione metabolism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6001.

Palmer ND, Stevens RD, Antinozzi PA, Anderson A, Bergman RN, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Metabolomic profile associated with insulin resistance and conversion to diabetes in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(3):E463–8.

Fennema D, Phillips IR, Shephard EA. Trimethylamine and trimethylamine N-oxide, a Flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3)-mediated host-microbiome metabolic axis implicated in health and disease. Drug Metab Dispos. 2016;44(11):1839–50.

Acknowledgements

Thank all the members of our team for their help in my experiments and the volunteers for their support and assistance in my research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Program of Qilu Institute of Technology (QIT 23TP016), the National Science Foundation of Shandong (ZR2022MC057), and the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0901702).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, WJM and FCS; methodology, FCS; software, YW; validation, QLL and YNZ; formal analysis, DYY; investigation, XYW; resources, QLL and DYY; data curation, FCS; writing—original draft preparation, WJM and FCS; writing-review and editing, YW and FCS; visualization, DYY and YNZ; supervision, XYW and YW; project administration, Ying Wang; funding acquisition, Wen-Jian Ma and Ying Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Guangxi University (approval No: gxdxdwll01 and date of approval 11 October 2019).

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1.

English comparison table of abbreviations of paper terms.

Additional file 3. Table S1.

1H-NMR signal assignment of main metabolites in mouse feces. Fig. S1. OPLS-DA scores plots of fecal metabolites between different mouse groups and cross validation by Permutations tests. (A) OPLS-DA plot of AG versus YG (R2Y = 0.994, Q2 = 0.991) shows distinct clustering and separation of fecal metabolites by age. (B) OPLS-DA plot of LDF and NDF (R2Y = 0.994, Q2 = 0.987) shows separation by diet. (C) OPLS-DA plot of HDF and NDF (R2Y = 0.994, Q2 = 0.987) shows more distinct separation by diet. R2Y and Q2 values > 0.5 indicate a high degree of model fit. Permutations testing shows all blue simulated Q2 values (left) are lower than the original point (right) and the regression line intercept is < 0.5, indicating the OPLS-DA models effectively discriminate between groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, F., Liu, Q., Yue, D. et al. Exploring the effects of the dietary fiber compound mediated by a longevity dietary pattern on antioxidation, characteristic bacterial genera, and metabolites based on fecal metabolomics. Nutr Metab (Lond) 21, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-024-00787-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-024-00787-y