Abstract

Background

Enteric infections caused by Salmonella spp. remain a major public health burden worldwide. Chickens are known to be a major reservoir for this zoonotic pathogen. The presence of Salmonella in poultry farms and abattoirs is associated with financial costs of treatment and a serious risk to human health. The use of bacteriophages as a biocontrol is one possible intervention by which Salmonella colonization of chickens could be reduced. In a prior study, phages Eϕ151 and Tϕ7 significantly reduced broiler chicken caecal colonization by S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium respectively.

Methods

Salmonella-free Ross broiler chickens were orally infected with S. Enteritidis P125109 or S. Typhimurium 4/74. After 7 days of infection, the animals were euthanased, and 25cm2 sections of skin were collected. The skin samples were sprayed with a phage suspension of either Eϕ151 (S. Enteritidis), Tϕ7 phage suspension (S. Typhimurium) or SM buffer (Control). After incubation, the number of surviving Salmonellas was determined by direct plating and Most Probable Number (MPN). To determine the rate of reduction of Salmonella numbers on the skin surface, a bioluminescent S. Typhimurium DT104 strain was cultured, spread on sections of chicken breast skin, and after spraying with a Tϕ11 phage suspension, skin samples were monitored using photon counting for up to 24 h.

Results

The median levels of Salmonella reduction following phage treatment were 1.38 log10 MPN (Enteritidis) and 1.83 log10 MPN (Typhimurium) per skin section. Treatment reductions were significant when compared with Salmonella recovery from control skin sections treated with buffer (p < 0.0001). Additionally, significant reduction in light intensity was observed within 1 min of phage Tϕ11 spraying onto the skin contaminated with a bioluminescent Salmonella recombinant strain, compared with buffer-treated controls (p < 0.01), implying that some lysis of Salmonella was occurring on the skin surface.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that phages may be used on the surface of chicken skin as biocontrol agents against Salmonella infected broiler chicken carcasses. The rate of bioluminescence reduction shown by the recombinant Salmonella strain used supported the hypothesis that at least some of the reduction observed was due to lysis occurred on the skin surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salmonellosis is one of the most commonly reported food borne diseases worldwide and remains a costly public health burden in many countries [1]. The World Health Organization estimates show Salmonella as a frequent cause of foodborne illness worldwide; responsible for 7.6 million cases in 2010, being Salmonella enterica accounted for 59, 000 and Salmonella Typhi for 52, 000 deaths [1].

Over 45, 000 cases of human salmonellosis were reported in the US in 2016 [2], and over 90, 000 cases reported in the EU in 2017 [3]. In 2013, the United States Department of Agriculture estimated the total cost of human salmonellosis in the US at over $3,6 billion [4]. The most recent FoodNet 2015 annual report shows that the number of hospitalized patients due to a Salmonella infection was almost twice that of Campylobacter, and comparable to all the hospitalizations due to infections caused by Campylobacter, Listeria, Shigella, E. coli, Vibrio or Yersinia combined [5].

Poultry, and particularly chickens, are widely accepted as a major source of Salmonella entering the human food chain [6, 7]. Improved cleaning and disinfection, biosecurity and the use of vaccines for breeding and laying flocks have helped to reduce the prevalence of Salmonella in chickens [8]. However, comprehensive biosecurity on farms is expensive and difficult to maintain and is a viable option only when there is a high value product and the consequences of Salmonella transmission are severe [9]. Even if good biosecurity is maintained on the farm, broiler chickens may become colonised with Salmonella if they are transported to the abattoir in contaminated crates [10].

Approximately 13.1% of chicken carcasses sampled in the EU tested positive for Salmonella [11]. The options for reducing contamination at this stage are limited by EU legislation. In the United States, contaminated broiler chicken carcasses can be washed in water containing chlorine. However, Salmonella is known to attach firmly to the skin of broiler chickens [12] and may not be readily accessible to free chlorine, or be relatively unaffected by it [13, 14]. Other chemical treatments e.g. trisodium phosphate, organic acids, sodium hydroxide, sodium metabisulphite and hydrogen peroxide have been used to reduce Salmonella counts on chicken skin, typically by 1–2 log10 CFU [15]. However, some studies suggest that the concentrations of these chemicals required to significantly reduce Salmonella contamination can result in an unacceptable deterioration in the organoleptic quality of the treated carcasses [15]. In the EU, regulation 853/2004 provides that no substance other than water (either potable or clean) can be used to remove surface contamination from foods of animal origin. This being the case, other means of controlling Salmonella in poultry processing are needed [10].

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is one method of reducing microbial contamination which has gained prominence over the years [16, 17]. Phages are natural parasites of bacteria and are ubiquitous in the environment at estimated levels of 1030 to 1032 PFU in the biome [18, 19]. The use of host-specific phage has been promoted as a cost-effective and adaptable approach to control zoonotic bacteria [20, 21]. Phages have unique advantages when compared with antibiotics [21]. For example, they replicate only in a targeted subset of bacteria, avoiding the imbalance of commensal flora (dysbiosis) often caused by the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. Additionally, they will only replicate as long as the targeted bacterium is present and so are naturally self-limiting [22]. Phages have been used to reduce the numbers of Campylobacter jejuni in commercial broilers by up to 5.0 log10 CFU g− 1 caecal contents [23]. Significant reductions in Salmonella numbers colonizing broiler chickens by using phage have also been reported [24, 25]. Both Campylobacter and Salmonella phages can be isolated readily from poultry excreta and the poultry farm environment [26,27,28] and as such would not introduce any new biological entity into the food chain if used therapeutically in poultry production.

The emergence of bacteriophage insensitive mutants (BIMs) has long been perceived as a major limitation of phage therapy [22]. Unlike chemotherapeutic agents such as antibiotics, phage constantly evolve to circumvent their host’s defences and resistant bacteria are often less fit or less virulent than their phage-sensitive counterparts [29]. However, the recolonization of animals with BIMs following phage treatment has been reported for several genera of zoonotic pathogens [23, 24, 30]. Ideally, phage should be applied in such a way as to restrict the opportunities for the emergence and spread of BIMs into the environment. In situations where phage greatly outnumber their hosts, the adsorption of many phage onto a single cell can cause death by “lysis from without” [31]. If this is carried out at the end of the processing line quickly followed by refrigeration, conceptually the emergence of BIMs would be greatly limited. Phage treatment in this instance would be arguably more easily optimised and controlled than phage therapy of live animals on a farm. A washed carcass surface, whilst providing some protection to resident bacteria [32, 33], is not the viscous matrix containing many potential decoys which may be encountered in the intestinal lumen of animals [34]. As such, phage treatment of carcasses may be more efficient than medicating live animals on the farm. Here we describe the use of Salmonella phages to reduce the numbers of two Salmonella serovars (Enteritidis and Typhimurium) on the surface of broiler chicken skin. We also use a bioluminescent Salmonella Typhimurium DT104 strain to determine how quickly this reduction may take place on the skin surface.

Methods

Sources and preparation of phage

All of the phages used in this study (Eϕ151, Tϕ10 and Tϕ11) were isolated from poultry excreta and abattoir effluent as reported previously [24]. All of these phage exhibited a clear plaquing phenotype on their respective host strains of Salmonella used in this study, indicating a lytic lifecycle on these strains. A lytic spectrum for phage Tϕ11 is presented in Supplementary Table 1, and electron micrographs of this phage are presented in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2. Phages were propagated on their host strains in nutrient broth (NB, CM0001, Oxoid, Basingstoke, UK) using a modification of a previously described protocol [35]. Briefly, a volume of fresh overnight culture of the host strain (0.1 ml) was added to 10 ml of pre-warmed NB (37 °C) in a 30 ml tube. To this was added 0.1 ml of a 106 PFU ml− 1 suspension of phage. The suspension was incubated statically at 37 °C for up to 8 h until lysis was apparent (compared with an uninfected control culture). The lysate was then filtered through a 0.22 μm pore-size filter (Millipore) and the phage titer determined using the method described below. Phage stocks were stored at 4 °C until required, but for no longer than 48 h before application. Phages in crude liquid lysates were concentrated and purified using PEG precipitation, as described previously [36]. Phage titres were determined by decimally diluting the phage suspension in SM buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4.7H2O, 0.01% w/v gelatin, reagents from Sigma) then adding duplicate 100 μl volumes of each dilution to equal volumes of approximately 8.0 log10 CFU ml− 1 of an overnight NB culture of Salmonella host strain and incubating for 15 min at 37 °C. Each of these suspensions was then added to 5 ml of molten overlay agar (NB containing 0.5% w/v bacteriological agar LP0011, Oxoid), gently shaken, and poured over pre-warmed (37 °C, 30 min) nutrient agar plates (NA, CM0003, Oxoid). After allowing the overlay to set, the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before examining for plaques.

Experimental birds

Salmonella-free Ross broiler chickens (36 days old, n = 36) were obtained from a commercial supplier (Lloyd Maunder, Devon, United Kingdom). Upon arrival at the University, the birds were separated into two equal groups and housed in groups of three in floor boxes in a controlled environment under strict conditions of biosecurity. To ensure that the experimental birds remained free of naturally-occurring Salmonella infection, faeces were collected periodically and screened for Salmonella by an enrichment step in modified Rappaport-Vassiliadis Soya peptone broth (RVS, CM0669, Oxoid), followed by streaking onto Brilliant Green Agar (BG, CM0329, Oxoid). Faecal (and later, caecal) samples were also collected to determine if any pre-existing Salmonella phages were present using the enrichment method for the environmental samples described previously [24]. On the day of arrival the birds were orally inoculated with 0.3 ml of an 8.0 log10 CFU ml− 1 suspension of either S. Enteritidis P125109 (group 1, n = 18), or S. Typhimurium 4/74 (group 2, n = 18). Both of these Salmonella strains were resistant to sodium nalidixate (20 μg ml− 1). All of the birds were killed by cervical dislocation 7 days after Salmonella challenge. The birds were hand plucked (without scalding or washing) and then two sections of skin (each 25 cm2) were carefully excised from the breast skin using sterile scissors and a disposable template, and placed into separate sterile Petri dishes. After the skin sections were collected from the birds and removed to a separate laboratory, the abdominal cavity was opened and the caeca were removed. This procedure was followed to ensure that there would be no possibility of gut contents contaminating the surface of the skin. The contents of the caecal lumen were collected in sterile universal tubes for Salmonella and phage enumeration using the same methods described above.

Phage treatment of skin

A total of 36 birds were used in the experiment, half of which were orally infected with S. Enteritidis and half with S. Typhimurium (see above). Two sections of skin were collected from each bird (72 skin samples total). One section of skin from each bird was sprayed with 1 ml (0.5 ml per side) of SM buffer (control) using a hand-operated plant spray, with the nozzle positioned approximately 10 cm from the surface of the skin and delivering 0.5 ml of liquid per spray. The other section was sprayed in an identical manner with 1 ml of a 9.0 log10 PFU ml− 1 of phage Eϕ151 (group 1), or Tϕ10 (group 2) for birds challenged with S. Enteritidis or S. Typhimurium respectively. After allowing 20 min to dry in a Class II biological safety hood, each skin section was transferred into a stomacher bag containing 50 ml of maximum recovery diluent (MRD, CM0733, Oxoid) and stomached for 1 min. Salmonellas in the stomachate were enumerated using two parallel methods. For the first method, decimal dilutions of the stomachate were prepared in MRD. Volumes (100 μl) of each dilution were then spread-plated onto BG agar containing 25 μg ml− 1 sodium nalidixate (BG nal) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h before examining for typical Salmonella colonies. The second method used the Most Probable Number technique (MPN) [37] using Rappaport Vassiliadis broth as the enrichment medium and BG nal agar for the plating medium.

Determining the rate of lysis in situ

In order to determine the rate of reduction of Salmonella numbers on the skin surface, a series of experiments were performed using a bioluminescent Salmonella host strain. The strain used was S. Typhimurium DT104 transformed with the pBBR1MCS5-LITE lux plasmid as described previously [38]. A linear relationship between photon and viable counts has previously been demonstrated for the plasmid construct when expressed in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (r2 = 0.982) [39] and in the S. Typhimurium DT104 used in this study (r2 = 0.9856) [40]. S. Typhimurium DT104 pBBR1MCS-5-LITE has been used successfully to assess the impact of in situ rapid heating and cooling on food surfaces, showing a strong correlation between bioluminescence and cell numbers (r2 = 0.97) [41, 42].

Sections of chicken breast skin were inoculated with 100 μl of a 106 CFU ml− 1 suspension of an overnight NB culture of the bioluminescent Salmonella strain, which had been washed twice and resuspended in MRD. The inoculum was spread evenly over the surface of the skin and then left to dry at 20 °C for 1 h in a Class II biological safety hood. After this time, two 25 cm2 sections were excised from the same piece of skin for each trial. The first section of skin (control) was sprayed with 0.5 ml of MRD; the second skin section (treated) was sprayed with 0.5 ml of a 109 PFU ml− 1 suspension of phage Tϕ11. The skin surfaces were viewed within 1 min of spraying, in a dark room with an ICCD 225 photon counting camera (Photek Ltd., St Lenards-on-Sea, East Sussex, TN38 9NS, UK). Photons were counted for 1 min at set intervals for up to 24 h at 20 °C. Each trial was repeated five times.

Statistical treatment of data

All statistical tests were performed on log10 transformed data. The D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test was used to determine if the data had an underlying normal distribution as this is a prerequisite for the use of parametric statistical tests. Where a normal distribution could not be determined, the median counts of Salmonella recovered from control and phage-treated skin sections were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test. The proportion of control and phage-treated skin sections that were culture positive for Salmonella were compared using Fisher’s Exact Test. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS® 14.0 for Microsoft Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA.

Results

Phage treatment of chicken skin

Data showing the recovery of S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium from chicken skin following treatment with phage is presented in Table 1. Salmonella and their phage were not recovered from any of the faecal samples taken from birds prior to experimental inoculation. No Salmonella phage could be isolated from the caecal content samples taken from the birds of the control group after slaughter. However, Salmonella spp. was recovered from the caeca of all birds used for the skin disinfection trials. The mean level of colonisation for birds infected with S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium (as determined from colony counts) was 4.0 ± 1.3 and 3.5 ± 1.0 log10 CFU g− 1 caecal contents respectively. When recovering Salmonella from some of the skin sections, all of the tubes inoculated for the MPN enumeration method tested positive for Salmonella. These samples were given a value of ≥3.04 log10 MPN per skin section (the upper detection limit of the MPN method used here). In addition, as the exact number of Salmonella in these samples was unknown, the mean and standard deviation could not be calculated accurately. As such, the median values and range are presented here. All of the control skin sections treated with buffer tested positive for Salmonella using the MPN method. The phage treatment of S. Enteritidis-contaminated skin sections resulted in a significant (p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U Test) median reduction of 1.38 log10 MPN per skin section compared with the control. Moreover, S. Enteritidis could not be recovered from 13/18 of the phage-treated skin sections, which was also significantly lower than the control group (p < 0.0001, Fisher’s Exact Test). Phage treatment of S. Typhimurium-contaminated skin sections led to similar results. The median recovery of S. Typhimurium was reduced significantly (p < 0.0001) by 1.83 log10 MPN per skin section compared with the control group. The proportion of Salmonella-positive skin sections following phage treatment (11/18, 61.1%) was also significantly lower than the control group (p = 0.0076).

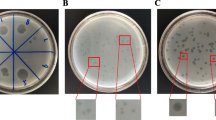

Demonstration of lysis on the skin surface

Photographs showing the photon counts from chicken skin sections experimentally inoculated with a bioluminescent strain of S. Typhimurium before and after spray treatment with a buffer or phage suspension are presented in Fig. 1. The mean photon count from the skin sections before buffer or phage treatment was 4.3 log10 RLU per skin section. The photon count for the skin treated with buffer increased slightly to 4.4 log10 RLU per skin section after spraying but this increase was not significant (p > 0.1). The mean photon count from the skin sections treated with phage fell from 4.3 to 4.1 log10 RLU which was a modest but statistically significant reduction compared with the control skin sections (p < 0.01). Following incubation for 24 h at room temperature (20 °C), the mean photon counts increased for the control skin sections (6.1 log10 RLU). The mean photon counts also increased for the phage-treated skin sections but reached a level significantly lower (p < 0.05) than the control skin sections (5.2 log10 RLU).

Negative image of control (C) and phage-treated (P) skin sections before spray treatment (1) and 2 min after spray treatment (2). A negative image of the logarithmic colour palette used by the Photek IFS32 software is presented on the right of the figure. Each colour represents the log10 number of photons collected at a given time point (1 min). The numbers on the right represent powers of ten (e.g. 2 = 102 photons). All images were processed identically using Adobe® Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, USA) on a Viglen Genie XL280 PC running Microsoft Windows XP

Discussion

The use of phages to control bacterial contamination of foods is an area of continuing interest and development. Since the FDA approved the limited use of phage to control Listeria in fresh foods, commercial interest in this area has increased considerably [43]. Several studies from around the world have highlighted the potential benefits of using phage to control zoonotic pathogens and food spoilage bacteria [44,45,46,47]. Salmonella continues to be a major global public health problem and many cases of human salmonellosis can be linked to the consumption of contaminated poultry products. It is widely accepted that poultry and associated products are a major source of entry into the human food chain for this pathogen. The entry of live birds contaminated with Salmonella into the abattoir can lead to widespread dissemination of this pathogen along the processing line and may lead to contamination of the final product [48]. Moreover, commercial cleaning procedures may not be sufficient to remove all Salmonellas from the processing line [49].

The numbers of both S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium were significantly reduced following phage treatment compared with the controls (p < 0.0001). Over 70% of the S. Enteritidis contaminated sections were culture-negative for Salmonella following phage treatment which suggests that this approach could be used in poultry processing plants to reduce the numbers of this zoonotic pathogen in the human food chain. If the chickens that arrive at the abattoir are carrying Salmonella, they will almost inevitably produce contaminated carcasses. In the present study, the use of commercial chickens experimentally colonised with Salmonella would be expected to result in a more realistic distribution of the pathogen across the carcass surface than, for example, sections of skin inoculated with a suspension of bacteria, which are models which have been used in previous studies [50, 51].

In the present study, median reductions of between 1.38 and 1.83 log10 MPN were achieved following phage treatment for skin contaminated with S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium respectively. These reductions largely agree with those recorded previously [44, 52, 53], and are similar to, or greater than reductions (~ 0.81 log10 CFU cm− 2) obtained following the chemical treatment of chicken skin with agents such as peroxyacetic acid, lactic acid and dichloroisocyanurate [50]. Indeed, this last study found that the reductions in Salmonella following phage treatment were not significantly different from those obtained using conventional chemical treatments at commercial levels of application. Another study found that reductions in various Salmonella serotypes of up to 5.0 log10 CFU ml− 1 could be achieved in vitro by combining phage and chemical treatments such as cetylpyridinium chloride and lauric arginate [53]. However, these reductions fell to between 1.6 and 2.5 log10 CFU cm− 2 when applied to chicken skin and meat surfaces.

A previous study concerning a Quantitative Risk Assessment (QRA) model of the link between the level of Salmonella contamination on broiler chicken carcasses and human infection indicated that a 50% reduction in chicken breast contamination at retail is predicted to reduce the probability of human infection by 40% [54]. Interestingly, the contamination levels used in this model ranged from ≤0.3 to 100 MPN g− 1 which is similar to levels recorded in the present study for naturally-contaminated chicken skin. This may suggest our findings are more directly relevant to existing models of Salmonella in the poultry meat supply chain and could be incorporated into future models examining the potential impact of such interventions on human disease. A separate QRA concluded that chemical decontamination agents such as chlorine could be powerful tools for decreasing Salmonella levels at the abattoir, these reductions were generally short-lived and negated by further processing steps [14]. As such, biocontrol agents such as phage which may retain some ability to infect Salmonella for some time after their application could produce a more sustained reduction in contamination than chemical agents. There is some experimental evidence that phage treatment can lead to sustained reductions of Salmonella numbers on the surface of chicken skin over 48 h at 4 °C [44]. An additional benefit of this would be that refrigerating the carcasses at 4 °C following phage treatment would not permit the regrowth of BIMs of Salmonella, which may not be the case if the phage were applied at farm level in live animals. Whether these effects can be replicated under commercial conditions has yet to be determined, however.

The use of a high titer phage suspension increases the probability of ‘lysis from without’, especially for a pathogen such as Salmonella which is generally present in low numbers on carcasses [55]. The speed of the reduction in Salmonella numbers, as seen on the surface of chicken skin, suggests that at least some lysis from without rather than active replication on the skin or lysis during the counting procedure. This may also be considered as an additional step towards reduction of BIMs emergence. Moreover, the time-lapse photographs of bioluminescent Salmonella on the skin surface (Fig. 2) demonstrate that regrowth of Salmonella following phage treatment is significantly slowed when compared with the control, even when in a favourable food matrix and incubation temperature. This observation suggests that the benefits of phage treatment may extend beyond the processing plant, into the transport chain and possibly all the way to consumers’ kitchens, hel** to reduce the risks of cross contamination during food preparation.

Time-lapse negative images of Salmonella growth on chicken skin following treatment with buffer (C) and phage (P) after 2 min, 3 h and 6 h, incubated at room temperature (~ 20 °C). A negative image of the logarithmic colour palette used by the Photek IFS32 software is presented on the right of the figure. Each colour represents the log10 number of photons collected at a given time point (1 min). The numbers on the right represent powers of ten (e.g. 2 = 102 photons). All images were processed identically using Adobe® Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, USA) on a Viglen Genie XL280 PC running Microsoft Windows XP

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that phages can be used to significantly reduce the surface contamination of chicken skin infected with S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium. The use of an autobioluminescent Salmonella strain supported the hypothesis that at least some of this reduction was due to lysis from without and occurred on the skin surface rather than in subsequent culture. The results of this study are promising, although further work needs to be done in order to optimise and adapt these phage treatments to an in-situ poultry industry setting.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BIM:

-

Bacteriophage insensitive mutants

- CFU:

-

Colony forming units

- MPN:

-

Most probable number

- PFU:

-

Plaque forming units

- PT:

-

Phage therapy

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases (foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015). 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/199350.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). National enteric disease surveillance: salmonella annual report, 2016. 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/pdfs/2016-Salmonella-report-508.pdf.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2017. EFSA J. 2018;16:5500 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/zoonoese-food-borne-outbreaks-surveillance-2017-updated.pdf.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Cost estimates of foodborne illnesses. 2014. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/cost-estimates-of-foodborne-illnesses.aspx5. Accessed 31 May 2020.

Foodborne Disease Active Surveillance Network 2015 Surveillance Report (Final Data). 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/foodnet/pdfs/FoodNet-Annual-Report-2015-508c.pdf. [Cited 2019 Feb 11].

Cogan TA, Humphrey TJ. The rise and fall of Salmonella Enteritidis in the UK. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94(Suppl):114S–9S. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.94.s1.13.x.

Cox NA, Richardson LJ, Bailey JS, Cosby DE, Cason JA, Musgrove MT. Bacterial contamination of poultry as a risk to human health. In: Mead G, editor. Food safety control in the poultry industry. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; 2005. p. 21–33.

Corry JE, Allen VM, Hudson WR, Breslin MF, Davies RH. Sources of Salmonella on broiler carcasses during transportation and processing: modes of contamination and methods of control. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:424–32. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01543.x.

Davies RH. Pathogen populations on poultry farms. In: Mead G, editor. Food safety control in the poultry industry. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; 2005. p. 101–35.

Byrd JA. Improving slaughter and processing technologies. In: Mead G, editor. Food safety control in the poultry industry. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; 2005. p. 310–32.

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Analysis of the baseline survey on the prevalence of Campylobacter in broiler batches and of Campylobacter and Salmonella on broiler carcasses, in the EU. EFSA J. 2010;8:1503. https://doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1503.

Lillard HS. Factors affecting the persistence of Salmonella during the processing of poultry. J Food Prot. 1989;52:829–32. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-52.11.829.

Lillard HS. Bactericidal effect of chlorine on attached salmonellae with and without sonification. J Food Prot. 1993;56:716–7. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-56.8.716.

Jeong J, Chon JW, Kim H, Song KY, Seo KH. Risk assessment for salmonellosis in chicken in South Korea: the effect of Salmonella concentration in chicken at retail. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour. 2018;38:1043–54. https://doi.org/10.5851/kosfa.2018.e37.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Risk assessments of Salmonella in eggs and broiler chickens. 2002. http://www.fao.org/3/a-y4392e.pdf.

Sulakvelidze A, Alavidze Z, Morris JG Jr. Bacteriophage therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:649–59. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.45.3.649-659.2001.

Summers WC. Bacteriophage therapy. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:437–51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.437.

Boyd EF, Brussow H. Common themes among bacteriophage-encoded virulence factors and diversity among the bacteriophages involved. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:521–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02459-9.

Rohwer F, Edwards R. The phage proteomic tree: a genome-based taxonomy for phage. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4529–35. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.184.16.4529-4535.2002.

Mangen MJ, Havelaar AH, Poppe KP, de Wit GA. Cost-utility analysis to control campylobacter on chicken meat: dealing with data limitations. Risk Anal. 2007;27:815–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2007.00925.x.

Sulakvelidze A, Barrow P. Phage therapy in animals and agribusiness. In: Kutter E, Sulakvelidze A, editors. Bacteriophages: biology and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2005. p. 335–80.

Connerton PL, Connerton IF. Microbial treatments to reduce pathogens in poultry meat. In: Mead G, editor. Food safety control in the poultry industry. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; 2005. p. 414–27.

Loc Carrillo C, Atterbury RJ, el-Shibiny A, Connerton PL, Dillon E, Scott A, Connerton IF. Bacteriophage therapy to reduce campylobacter jejuni colonization of broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:6554–63. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.11.6554-6563.2005.

Atterbury RJ, Van Bergen MA, Ortiz F, Lovell MA, Harris JA, De Boer A, Wagenaar JA, Allen VM, Barrow PA. Bacteriophage therapy to reduce salmonella colonization of broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:4543–9. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00049-07.

Borie C, Albala I, Sanchez P, Sanchez ML, Ramirez S, Navarro C, Morales MA, Retamales AJ, Robeson J. Bacteriophage treatment reduces Salmonella colonization of infected chickens. Avian Dis. 2008;52:64–7. https://doi.org/10.1637/8091-082007-Reg.

Connerton PL, Loc Carrillo CM, Swift C, Dillon E, Scott A, Rees CE, Dodd CE, Frost J, Connerton IF. Longitudinal study of campylobacter jejuni bacteriophages and their hosts from broiler chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3877–83. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.7.3877-3883.2004.

El-Shibiny A, Connerton PL, Connerton IF. Enumeration and diversity of campylobacters and bacteriophages isolated during the rearing cycles of free-range and organic chickens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:1259–66. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.71.3.1259-1266.2005.

Grajewski BA, Kusek JW, Gelfand HM. Development of a bacteriophage ty** system for campylobacter jejuni and campylobacter coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22:13–8.

Smith HW, Huggins MB. Effectiveness of phages in treating experimental Escherichia coli diarrhoea in calves, piglets and lambs. J Gen Microbiol. 1983;129:2659–75. https://doi.org/10.1099/00221287-129-8-2659.

O'Flynn G, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Coffey A. Evaluation of a cocktail of three bacteriophages for biocontrol of Escherichia coli O157: H7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3417–24. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.70.6.3417-3424.2004.

Delbruck M. The growth of bacteriophage and lysis of the host. J Gen Physiol. 1940;23:643–60. https://doi.org/10.1085/jgp.23.5.643.

Chantarapanont W, Berrang ME, Frank JF. Direct microscopic observation of viability of campylobacter jejuni on chicken skin treated with selected chemical sanitizing agents. J Food Prot. 2004;67:1146–52. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-67.6.1146.

Kim KY, Frank JF, Craven SE. Three-dimensional visualization of Salmonella attachment to poultry skin using confocal scanning laser microscopy. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1996;22:280–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-765x.1996.tb01161.x.

Weld RJ, Butts C, Heinemann JA. Models of phage growth and their applicability to phage therapy. J Theor Biol. 2004;227:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5193(03)00262-5.

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Preparing stocks of bacteriophage lambda by small-scale liquid culture. In: Sambrook J, Russell AD, editors. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, vol. 1. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. p. 2.38–9.

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Precipitation of bacteriophage lambda particles from large-scale lysates. In: Sambrook J, Russell AD, editors. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, vol. 1. 3rd ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2001. p. 2.43–4.

Collins CH, Lyne PM, Grange JM. Microbiological methods. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995.

Baldwin A, Nelson SM, Lewis RJ, Dowman A, Alloush HM, Salisbury V. Development of a range of bioluminescent food borne pathogens for assessing in-situ heat inactivation and recovery of bacteria during heat treatment of foods. In: Tsuji A, Maeda M, Matsumoto M, Kricka LJ, Stanley P, editors. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescence, progress and perspectives. Singapore: World Scientific Publishers; 2005. p. 369–72. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812702203_0087.

Thorn RM, Nelson SM, Greenman J. Use of a bioluminescent Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain within an in vitro microbiological system, as a model of wound infection, to assess the antimicrobial efficacy of wound dressings by monitoring light production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3217–24. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00302-07.

Turner D. Characterisation of three bacteriophages infecting serovars of Salmonella enterica. PhD thesis: University of the West of England; 2013. https://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/secure/22112/.

Lewis RJ, Baldwin A, O'Neill T, Alloush HA, Nelson SM, Dowman T, Salisbury V. Use of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 expressing lux genes to assess, in real time and in situ, heat inactivation and recovery on a range of contaminated food surfaces. J Food Eng. 2006;76:41–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.05.023.

Lewis RJ, Robertson K, Alloush HM, Dowman T, Salisbury V. Use of bioluminescence to evaluate the effects of rapid cooling on recovery of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 after heat treatment. J Food Eng. 2006;76:49–52.

Leverentz B, Conway WS, Alavidze Z, Janisiewicz WJ, Fuchs Y, Camp MJ, Chighladze E, Sulakvelidze A. Examination of bacteriophage as a biocontrol method for Salmonella on fresh-cut fruit: a model study. J Food Prot. 2001;64:1116–21. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-64.8.1116.

Goode D, Allen VM, Barrow PA. Reduction of experimental Salmonella and campylobacter contamination of chicken skin by application of lytic bacteriophages. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:5032–6. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.69.8.5032-5036.2003.

Goodridge LD, Bisha B. Phage-based biocontrol strategies to reduce foodborne pathogens in foods. Bacteriophage. 2011;1:130–7. https://doi.org/10.4161/bact.1.3.17629.

Hudson JA, Billington C, Carey-Smith G, Greening G. Bacteriophages as biocontrol agents in food. J Food Prot. 2005;68:426–37. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028x-68.2.426.

Moye ZD, Woolston J, Sulakvelidze A. Bacteriophage applications for food production and processing. Viruses. 2018;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040205.

Lillard HS. The impact of commercial processing procedures on the bacterial-contamination and cross-contamination of broiler carcasses. J Food Prot. 1990;53:202–4. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X-53.3.202.

Olsen JE, Brown DJ, Madsen M, Bisgaard M. Cross-contamination with Salmonella on a broiler slaughterhouse line demonstrated by use of epidemiological markers. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;94:826–35. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01911.x.

Hungaro HM, Mendonça RCS, Gouvêa DM, Vanetti MCD, Pinto CL. Use of bacteriophages to reduce Salmonella in chicken skin in comparison with chemical agents. Food Res Int. 2013;52:75–81.

Milho C, Silva MD, Melo L, Santos S, Azeredo J, Sillankorva S. Control of Salmonella Enteritidis on food contact surfaces with bacteriophage PVP-SE2. Biofouling. 2018;34:753–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927014.2018.1501475.

Petsong K, Benjakul S, Chaturongakul S, Switt AIM, Vongkamjan K. Lysis profiles of Salmonella phages on Salmonella isolates from various sources and efficiency of a phage cocktail against S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium. Microorganisms. 2019;7. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7040100.

Sukumaran AT, Nannapaneni R, Kiess A, Sharma CS. Reduction of Salmonella on chicken meat and chicken skin by combined or sequential application of lytic bacteriophage with chemical antimicrobials. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;207:8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.04.025.

Smadi H, Sargeant JM. Quantitative risk assessment of human salmonellosis in Canadian broiler chicken breast from retail to consumption. Risk Anal. 2013;33:232–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01841.x.

Russell SM, Cox NA, Bailey JS. Sampling poultry carcasses and parts to determine bacterial levels. J Appl Poult Res. 1997;6:234–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ann Cornish and Jill Harris from the University of Bristol for technical assistance. From the University of the West of England we thank Vyvyan Salisbury, Robin Thorn and Thomas Vattakaven for their assistance with the bioluminescence studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/M028399/1 Title: A bacteriophage-based approach to reducing infections caused by antibiotic resistant Escherichia coli; and the European Union FP6 project SUPASALVAC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RA and GR designed the experiments; RA, MR and GR performed the experiments; RA and PB analysed the data; RA, VMA and AMG wrote the paper/ contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The current work approval and licence (30/2069) was granted by the UK Home Office under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and following local ethical approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Lytic spectra of Salmonella bacteriophage Tφ11 determined on 35 Salmonella strains. Results were recorded as follows: +++, confluent lysis; ++, semiconfluent lysis; +, individual plaques, −, no lysis.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 1.

Transmission Electron Micrograph of phage Tφ11.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Figure 2.

Transmission Electron Micrograph of phage Tφ11.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Atterbury, R.J., Gigante, A.M., Rubio Lozano, M. et al. Reduction of Salmonella contamination on the surface of chicken skin using bacteriophage. Virol J 17, 98 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01368-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-020-01368-0