Abstract

The rapid advancement of wearable biosensors has revolutionized healthcare monitoring by screening in a non-invasive and continuous manner. Among various sensing techniques, field-effect transistor (FET)-based wearable biosensors attract increasing attention due to their advantages such as label-free detection, fast response, easy operation, and capability of integration. This review explores the innovative developments and applications of FET-based wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Beginning with an introduction to the significance of wearable biosensors, the paper gives an overview of structural and operational principles of FETs, providing insights into their diverse classifications. Next, the paper discusses the fabrication methods, semiconductor surface modification techniques and gate surface functionalization strategies. This background lays the foundation for exploring specific FET-based biosensor designs, including enzyme, antibody and nanobody, aptamer, as well as ion-sensitive membrane sensors. Subsequently, the paper investigates the incorporation of FET-based biosensors in monitoring biomarkers present in physiological fluids such as sweat, tears, saliva, and skin interstitial fluid (ISF). Finally, we address challenges, technical issues, and opportunities related to FET-based biosensor applications. This comprehensive review underscores the transformative potential of FET-based wearable biosensors in healthcare monitoring. By offering a multidimensional perspective on device design, fabrication, functionalization and applications, this paper aims to serve as a valuable resource for researchers in the field of biosensing technology and personalized healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The popularity of wearable biosensors has been increasing with the development of smartphones and other mobile devices, offering the remarkable capability of continuous and real-time collection of physiological data, thereby providing valuable insights into individuals’ performance and health [1, 2]. These biosensors, which incorporate biological recognition elements into their design, hold great potential in managing chronic conditions and supporting remote monitoring. This capability was not possible before with traditional analytical methods. Despite their high sensitivity and complexity, lab-based approaches often lack real-time and point-of-care capabilities. For instance, mass spectrometry [3, 4] can detect a wide range of biomarkers simultaneously. However, its reliance on laboratories, trained technicians, high cost, and time-consuming procedures makes it impractical from a decentralized clinical perspective. Similarly, ELISA [5, 6], which is extensively used in laboratory environments for clinical diagnosis of biochemical species, suffers from lengthy analysis time, limited usability outside traditional diagnostic laboratories, reliance on bulky analytical instruments [7], and the requirement for larger sample sizes [8].

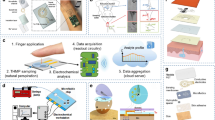

To date, considerable efforts have been dedicated to the development of next-generation wearable biosensors. Early studies focusing on the non-invasive and dynamic measurement of biomarkers available in biofluids (e.g. interstitial fluid, saliva, tear, sweat). These wearable biosensors have been demonstrated for analytes collected from head-to-toe application sites, Fig. 1 [9]. Approaches for detecting biomolecules are for isntance electrochemical, micro-cantilever, fluorescence, colorimetric, chemoresistive and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) techniques, which have their respective advantages and disadvantages [10, 11]. These sensors offer high specificity and can detect substances at low concentration, making them suitable for early detection and real-time analysis. Electrochemical based immunosensors, including amperometric, impedimetric and potentiometric, have demonstrated novel and unique detection platform [12, 13]. Among these sensors, FETs have gained significant interest due to their advantages such as quick sample screening, label-free detection, wide dynamic range, and cost-effective fabrication processes, particularly on flexible substrates surpassing the capabilities of existing methods [14, 15].

Wearable FET biosensors for diagnostics and health monitoring applications. Clockwise from top: Contact-lens biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [16] Copyright 2019 Wiley); Smart patch biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [1] Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society); Smart Watch biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [17] Copyright 2022 Science); Smart array biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [18] Copyright 2020 Elsevier); Passive Microfludic Sweat Analyzer biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [19] Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society); Smart textile biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [20] Copyright 2016 Wiley); Saliva test biosensor (reprinted with permission from Ref. [21] Copyright 2019 Elsevier)

Classical field effect transistors (FET) have been the backbone of modern electronic devices with gate-controlled current flowing through semiconducting channels. State-of-the-art micro/nanofabrication technologies make it possible to jam pack billions of transistors in a chip with size smaller than a human finger. This degree of miniaturization has led to a substantial increase in processing power, but at the same time a reduction in power consumption, and production cost. A few outstanding reviews exist on wearable FET sensors in different aspects. Li et al. [22] reviewed the recent advances in wearable devices based on flexible field-effect transistors including sensors for pressure, temperature, chemical, and biological analytes. Chen et al. [23] provided critical evaluation on multidisciplinary technical details, including sensing mechanism in detecting biomolecules, response signal type, sensing performance optimization, and the integration strategy. Dai et al. [24] review the recent advances of field-effect transistor sensors based on 2D materials, from the material, operating principles, fabrication technologies, proof-of-concept applications, and prototypes, to the challenges and opportunities for their commercialization.

The present review provides a comprehensive overview on FET-based wearable biosensors from various perspectives including sensing mechanisms, classification of device according to gating mode, materials, geometry, recognition elements and sampling. Next, we describe fabrication and surface modification techniques of FET biosensors. Furthermore, we outline the various principles of probe that can selectively detect the specific biological elements in terms of enzyme, antibody/nanobody, aptamer and ion-selective membrane. Additionally, we discuss physiological relevance of monitoring key biomarkers with wearable biosensors. Finally, we critically review and discuss challenges that greatly affect the future development of wearable FET biosensor.

Structure and working principle of FETs

Field-effect transistor-based sensors (FET) are analytical devices that can selectively detect the concentration of a biological molecules. FET sensors typically comprise: a dielectric insulating layer, a semiconductor layer, and three electrodes (drain, source, and gate), Fig. 2.

Illustration of a biological and chemical FET sensor platform. From top to bottom: Devices are fabricated and packaged by micromachining processes; Sensing surfaces are functionalized with probes to capture biomarkers; Charged biomarkers causes potential changes in sensing channels, then various electrical characteristics are measured; Analog signals are collected, transformed to digitals then logged to "cloud” data services for remote accesses

The flow of current (IDS) between drain and source electrodes of a FET is regulated by a variable voltage (VGS) applied between the gate and source electrodes [22]. This applied voltage prompts a redistribution of the electric field within the dielectric layer, leading to the creation of a dual-electric layer. Consequently, charge carriers can move through the semiconductor layer close to the interface adjacent to the dielectric layer [25, 26]. The conductive behaviors displayed by these charge carriers vary depending on the relationship in energy levels between the semiconductor and the drain/source electrodes. More specifically, either holes (h+) or electrons (e−) can act as charge carriers in the semiconductor layer. In an n-type FET, when a positive voltage is applied to the gate, a channel is generated, allowing electrons to travel from the source to the drain, i.e., conduction [27]. Conversely, if a negative gate voltage is applied, the n-type channel is sealed off, preventing conduction by the carriers. With a p-type FET, the scenario unfolds in reverse, wherein a positive (negative) gate voltage deactivates (activates) the transistor.

Charged molecules that bind to the active layer, whether that be a gate electrode or a semiconductor channel, can cause the charges within the semiconductor material to redistribute, thereby modifying the conductance of the FET channel. When the target analyte interacts with the functionalized sensing layer of the FET device—typically either a semiconducting or a dielectric layer—it alters the electrical characteristics of this active layer at the molecular level. Consequently, the distribution of charge carriers within this layer changes, resulting in fluctuations in the output current of the FET. These fluctuations which can be measured as electrical signals, can either indicate the presence of the target analyte or changes of its concentration [22].

The Debye screening length, also called Debye length (λD), is a physical distance where the charged analyte is electrically screened by the ions in the solution, strongly influences the sensitivity of immunosensor or electrochemical devices in high ionic strength media. The Debye length (λD) in an electrolyte is given as [28]:

Where ε0 corresponds to the vacuum permittivity; εr is the relative permittivity of the medium; kB is the Boltzmann constant; T is the absolute temperature; NA is the Avogadro number; q is the charge on an electron; and I is the ionic strength of the solution. According to this Debye theory, an increase in ion concentration reduces the Debye length due to charge screening by counter-ions, lowering the sensitivity of the device.

Classification of device

Figure 3 demonstrates different classification systems for FET biosensors according to architecture, material, geometry, recognition and sampling.

Architecture

This classification method divides the gate architecture of FET biosensors into single gating (top-gate, back-gate, liquid-gate, side-gate) or complex-gating (dual-gate, floating-gate, extended-gate), Fig. 4. Additionally, FETs can be divided into top-contact and bottom-contact types according to the contact positions of the semiconductor and source/drain electrodes. Source/drain electrodes are deposited on an insulating layer in the top-contact type, whereas the source/drain electrodes are positioned above semiconductor layers in the bottom-contact type [29]. Generally, top-contact structures have a lower contact resistance and a higher mobility due to the technology used to fabricate the sensors. However, the bottom-contact types tend to have shorter channels.

Typically, top-gate biosensors are effective detectors as the top gate can also be used as the sensing component instead of semiconductor channel, Fig. 4a. Additionally, producing top-gate biosensors is relatively simple, requiring only contact lithography patterning and metal lift-off technology during the fabrication process [30]. For instance, Chu et al. [31] developed an electric-double-layer FET that can directly detect various proteins in physiological high ionic strength solutions. The gold top gate in this device is separated from the active channel. The probe is immobilized on the gate, resulting in sensitive detection of the analyte with a concentration as low as 1 fM.

Compared to top-gate configuration, back-gate biosensors often have a larger sensing area, Fig. 4b. In this type of sensor, the silicon substrate is commonly employed as the back gate, and silicon dioxide serves as the dielectric layer for the gate [30]. Guo et al. [32] developed a MoS2 FET, employing a basic back-gate configuration directly fabricated onto a SiO2/Si substrate through the standard nanofabrication process. This high-performance MoS2 transistor is large in area and ultrathin, making it relatively easy to integrate into a soft, smart contact lens where photodetectors, glucose sensors, and temperature sensors monitor the tear fluid.

The liquid-gate (also called solution-gate) is the most common type of FET as it presents the best simulation of the human physiological environment for binding biomolecules, Fig. 4c. When the FET operates in an electrolyte solution, reference electrodes are immersed in a solution, which provides bias voltage through a liquid gate. An electric field establishes at the interface between the electrolytes and the semiconductor. As a result, an electric double layer (EDL) forms, and modulates the potential and conductivity of the channel [24]. This EDL at the semiconductor interface not only makes the devices highly sensitive to a range of analytes, but it also allows for operation at low gate potentials. Wang et al. [17] developed a wearable liquid gate In2O3-FET, which relies on aptamers to measure cortisol level in sweat. An Ag/AgCl reference electrode on the chip is fabricated simply by depositing Ag/AgCl ink, which supports linear gate-source sweep voltage biasing.

Another FET architecture is side gate (or co-planar gate). In this type, the gate is placed in the same plan as the channel layer (Fig. 4d). In this case, the side gate can simultaneously bias several nearby semiconductor channels for multi-functional biosensing. For instance, simultaneous monitoring of temperature, pH, and neurotransmitters (dopamine and serotonin) was achieved in a multiplexed platform using this architecture [33].

In a dual-gate FET, two insulated gates (bottom-gate and top-gate electrodes, or bottom-gate and liquid gate electrodes) offer two different VGS for independent modulation, Fig. 4e. This configuration increases the sensor’s response, improves signal-to-noise ratio, and reduces signal drift and hysteresis [34]. Capua et al. [35] developed a SiNW FET using this configuration to detect C-reactive protein. The sensor has excellent stability, low hysteresis, great sensitivity, and a negligible shift over time. These properties are highly advantageous in applications, where the biomarkers in body fluids need to be continuously monitored.

Floating-gate type FET sensors are designed to work in solutions, and are a relatively recent development. An additional metal floating control gate electrode is electrically isolated between the original top-most gate (now called the control gate) and the channel, creating a floating node in direct current. This floating node can store the charge and control the channel’s conductivity, Fig. 4f. An oxide layer surrounding the floating gate keeps the electrons trapped such that the device can store an electric charge for an extended period of time without needing to connect to a power supply. Liang et al. developed a wafer-scale uniform floating-gate carbon nanotube FET system [36]. An ultrathin Y2O3 high-κ dielectric layer in the floating-gate structure increases the sensitivity and amplifies the response of the FET, as compared to counterparts without a Y2O3 layer. The improvement is attributed to a dominant chemical gate-coupling effect in the response mechanism of the sensor [36]. The theoretical LOD is as low as 6 particles/mL.

Extended-gate FET (EG-FET) expands the gate electrode off-chip to enforce separate wet and dry environments, Fig. 4g. Only the detector portion is immersed into the solution, while the transducer remains in a completely dry environment. The sensor electrode is linked to a MOSFET gate and elongated with a metal signal line. The advantage of this setup is that the majority of the electrical signals is isolated from the measurement environment, making it a straightforward and dependable encapsulation approach. This configuration also minimizes environmental interference, including light-induced drift [37]. Fabricating this device is also substantially simple, allowing post-processing steps. In this category, Yang et al. [38] developed a low-cost and flexible ITO/PET EG-FET with roll-to-roll fabrication. The extended gate in this device has a simple enzyme functionalization for the detection of urea.

Semiconductor materials

Various semiconductor materials have been used to fabricate FET, including silicon [35], metal oxides [18], III-V materials [39], transition metal dichalcogenides [39], organic semiconductors [40], graphene [2], carbon nanotubes [41], and black phosphorous [42]. Several criteria need to be considered for selecting the semiconductor for a bioFET sensor. These include the electrical and mechanical stability of the measurement environment, the sensitivity of the material to light and temperature, the availability of the material in commercial quantities, and the compatibility is with large-scale fabrication on flexible substrates [43]. Table 1 provides a summary of the potential impact of material properties on biosensors.

FET-based wearable devices have been successfully applied to materials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, silicon, In2O3, MoS2, ZnO, zinc titanium oxide, and organic semiconductors. These materials are compatible with substrates such as Si/SiO2, polyimide, polyester PET, poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS), polyethylenenaphthalate (PEN). When selecting a substrate, one must consider the processing temperature involved in the device fabrication, along with other physical properties of the substrate such as the glass transition temperature, flexural modulus, Young’s modulus, optical transparency, thermal expansion, and adhesion to active materials.

Semiconductor geometry

Nanoscale semiconductor materials have typically a thickness of a single atom or perhaps a few atoms. Measuring less than 5 nm deep, their lateral size can range from sub-micrometers to centimeters [24]. Table 2 summarizes the strengths and weaknesses of some of the common nanoscale materials.

Other classifications

Another way to categorize FET sensors is based on the substance used to recognize the analyte. For example, if a FET is designed to detect an analyte through an enzymatic reaction, the sensor is called an enzyme-FET or an EnFET. Other categories include ISFETs, aptaFETs, immunological FETs, and DNA-FETs. For wearable devices, several recognition elements also known as probes have been used to monitor biomarkers in body fluids. Finally, wearable FET device can be classified based on the biofluid samples, such as sweat, tear, saliva, ISF. Further details about recognition element and samples will be discussed in other sections of this paper.

Fabrication of semiconductor materials

The main function of semiconductors in FET sensors is to facilitate the flow of current, which critically impacts the sensitivity [43]. Various approaches can be employed to fabricate FET sensors, including top-down machining techniques, bottom-up synthesis techniques, and assembly strategies. Figure 5 summarized common fabrication techniques of thin films along five qualitative parameters, including cost, quality, repeatability, scale, and ease of processing [24].

Qualitative comparison of common fabrication techniques of thin films. Repaint with permission from Ref. [24].

The top-down approach is a process of breaking down the bulk materials into smaller, micro and nanoscale structures. For silicon nanowire (SiNW)-FET sensors, top-down machining is well established with advanced lithography and microfabrication techniques to make microdevices in batch in a controlled setting, allowing both cost-effective and easily scalable to produce large quantities [45]. Commencing with a silicon-on-isolator (SOI) substrate, the SiNW sensor structure is designated using pattern transfer methodologies, including electron-beam lithography, nanoimprint lithography, or sidewall transfer lithography. The subsequent etching process encompasses reactive ion etching, wet chemical etching, or a hybrid approach integrating both techniques, facilitating the transfer of the designed structure onto the uppermost silicon layer of the SOI substrate. Further microfabrication techniques are then employed to finalize the devices with source drain, ohmic contact establishment, gate dielectric layer implementation, and passivation layer. For top-down machining of materials other than silicon, mechanical/liquid exfoliation is a common technique. Mechanical exfoliation is reported to produce exceptional quality with minimal defects by peeling-off atomically thin layers from a bulk material [46, 47]. Graphene, the first 2D materials discovered in a laboratory, was prepared by this method [48], simply with adhesive tapes. However, the process is time-consuming and labour-intensive, especially when aiming to obtain large area of thin flakes [45]. It is also hard to get uniform samples as there are lots of flakes with different number of layers randomly dispersed on the substrates [49]. Mechanical exfoliation is one of the most used top-down techniques for producing metal oxide nanosheets with high quality and degree of crystallinity [50]. Recently, Zhang et al. reported a novel mechanical exfoliation process to prepare MoS2 nanoflakes with thermal treatment to improve the size and yield of material [51]. Liquid phase exfoliation, on the other hand, offers an alternative replacement to isolate and disperse thin layers of nanomaterials from their bulk crystals in a liquid medium. The technique involves breaking down the bulk crystals of the material into thinner layers by applying mechanical or ultrasonic forces. The resulting nanosheets or nanoparticles can be easily dispersed in a liquid solvent to form a stable colloidal suspension [52]. Liquid exfoliation typically produces materials with high yield, good quality and rather low cost [49]. This technique has been applied to a wide range of material including carbon nanotube [53], graphene [54, 55], and black phosphorus [56, 57].

Bottom-up synthesis involves assembling and growing materials from atomic or molecular precursors to form desired structures. Following this approach, SiNWs were vertically grown on a silicon substrate using various methods such as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [58], oxide assisted growth [59] or metal-assisted chemical etching [60]. In the case of metal oxides, various structural forms such as nanoribbons, nanowires, nanorods, nanobelts, and nano thin films, can be created using vapor-phased techniques, which include depositing chemical vapors and physical vapors [43]. While CVD synthesizes nanostructures through chemical reactions in the vapor phase with the assistance of a noble metal catalyst. In contrast, physical vapor deposition (PVD) produces nanostructures by either thermal evaporation or plasma. CVD is also especially useful for transition metal dichalcogenides such as MoS2 [61], as large-scale materials can be grown on different substrates by CVD, and the materials can be easily transferred to other substrates [62]. However, this method needs an accurate control of experimental conditions, so it is still too complicated and expensive for mass-production [49]. Molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE) is a physical vapor deposition technique that can grow thin films of single crystals from various materials, including gallium nitride [63], zinc oxide [64] and organic semiconductor [65]. This sophisticated technique offers atomic-level precision over the growth of crystalline materials in an ultra-high vacuum environment. However, MBE has high equipment and operation costs, and may face challenges in scaling up due to its relatively slow growth rate [66]. Similar to CVD, atomic layer deposition (ALD) is a thin film deposition technique relying on surface chemical reactions of gaseous precursors, but these surface reactions occur through self-saturating gas-surface reaction mechanisms [67]. ALD offers the capacity for layer-by-layer deposition with exceptional control over film thickness, outstanding uniformity, and unparallel conformal coverage on nanostructured surfaces [68], albeit at the expense of its high cost and slow deposition rate [69]. Solution-phase synthesis routes, such as sol–gel and hydrothermal synthesis, can be employed to produce many metal oxide nanostructures and thin films [43]. These solution-based methods provide a cost-effective approach to create a diverse array of metal oxide nanostructures with controllable properties [29].

Assembly strategies are used to arrange and position nanomaterials onto specific locations of the FET sensor. For example, the floating-coffee-ring driven assembly takes advantage of the self-assembly behavior of nanoparticles in evaporating liquid droplets, resulting in a ring-like pattern of the deposited nanoparticles [70]. Dynamic-template-assisted meniscus-guided coating is another assembly strategy where the controlled motion of a template or meniscus is used to guide the deposition of materials onto desired areas of the sensor surface [71, 72].

These fabrication techniques contribute to the versatility and functionality of FET sensors, allowing for tailored sensor design and performance optimization in various applications. It is important to note that these techniques are not exhaustive. Advancements in nanotechnology and material science continue to expand the repertoire of fabrication methods for FET sensors.

Functionalization techniques of semiconductor surface

Surface functionalization or immobilization involves attaching biological receptors onto a matrix or support, either on the surface or within it. This attachment can occur through physical or chemical means, through direct or indirect techniques, as long as ultimately the bioreceptors are coupled to the active layer of the sensor [73].

Regardless of the specific method used for immobilization, the technique should be straightforward to perform, highly reproducible, effective at preventing non-specific bindings, and robust to extreme environmental conditions [74]. Additionally, following the immobilization, the biomolecules should remain both easily accessible and chemically inert to the host structure. This will ensure the biosensor remains both functional and stable over time.

Physical adsorption

The simplest method of immobilizing biomolecules on a surface is physical adsorption (physisorption). This process involves attaching the biomolecules to the surface using weak and noncovalent binding or deposition forces, such as electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding interactions between the sensor surface and the target analyte (Fig. 6a) [75]. In the physisorption process, biomolecules are typically immobilized on an electrode/semiconductor surface by immersing the surface into a solution containing the biomolecules and allowing them to bind to the surface during a fixed incubation period. A minimum bulk receptor concentration of 1 µM is required for a typical incubation time of 1 h to guarantee maximum surface coverage [76]. Subsequently, the surface is washed with a buffer solution to remove any unbound biomolecules [75].

However, there are certain limitations associated with physisorption. Due to the weak and noncovalent nature of the interactions, the performance, stability, and reusability of the sensor can be significantly affected by factors such as temperature, pH, concentration, and ionic strength. As a result, this method has not received extensive attention. One major drawback of immobilization through physisorption is the possibility of desorption of the bioreceptors from the surface during measurements, leading to decreased sensitivity. Additionally, non-specific adsorption of interfering molecules on the sensor surface is another issue that can negatively impact the sensor's accuracy and specificity [75].

In particular, Guo et al. [32] fabricated a MoS2 FET immobilized with glucose oxidase via physical adsorption. The measured glucose concentration in phosphate buffer was from 0.1 mM to 0.6 mM, which is within the typical range of human tear’s glucose level. Similarly, Zong et al. [44] developed a glucose sensor with ZnO FET. The FET sensor is fabricated via hydrothermal growth of semiconducting ZnO nanorods between source and drain microelectrodes. Following the fabrication process, the semiconductor was incubated with glucose oxidase solution overnight to maximize the adsorption. This approach was able to detect glucose with an LOD of 1 μM.

Chemical modification

Chemical approaches offer a solution to address the limitations of physisorption and generally achieve better performance. These approaches involve creating a strong and stable attachment between biomolecules and the electrode surface through covalent bonding, crosslinking, and bioconjugation affinity using the functional groups present on the surface [73].

In the case of FET sensors, the surface is functionalized with a chemical agent that uses covalent bonds to immobilize specific bioreceptors. Covalent immobilization provides a stable and permanent attachment of the bioreceptor to the FET surface, enhancing the device’s sensitivity and specificity. This approach ensures a reliable and efficient biosensing system capable of accurately detecting the target analyte [43].

Prior to functionalization, the semiconductor surface should be activated with either UV-ozone, oxygen plasma [38] or an ammonia/hydrogen peroxide mixture. These treatments create − OH or − COOH groups on the surface, making it more receptive to a reaction with any organosilanes during the subsequent functionalization step.

When it comes to metal oxide semiconductors, organo-silanization is a commonly used technique for immobilizing biomolecules on the surface of oxides such as SiO2 and various forms of glass. This process involves functionalizing the oxide surface with specific organosilane compounds. Two frequently used alkoxysilanes for this purpose are 3-aminopropyl-triethoxysilane (APTES) and 3-glycidyloxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GOPTS). Other alkoxysilanes like 3-mercaptopropyltrimethoxysilane and 3-trimethoxysilyl propyl aldehyde may also be used. Following APTES functionalization, the amine functional groups can be further reacted with a linker such as m-Maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (MBS, Fig. 6b) or glutaraldehyde (GA, Fig. 6c). These linkers introduce functional groups that can be covalently bound to various molecular thiol- or amine- containing probes, such as nucleotide probes, aptamers, antibodies, nanobodies, proteins, or enzymes. For instance, Liu et al. [33] functionalized In2O3 FET platform with thiolated aptamer using APTES and MBS linker. The platform was able to simultaneously detect neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and dopamine, in real-time with a detection range from 10 fM to 1 μM. Similarly, Hayashi et al. [77] used APTES and GA linker to immobilize Jacalin into the surface of SiO2 bioFET. The device could specifically detect secretory immunoglobulin A in sweat at concentrations ranging from 0.1 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL. These studies demonstrated the utility of FET biosensors in monitoring condition on mental health to prevent depression.

Approaches with phosphonate chemistry offer some advantages over organosilanes [43, 78]. First, they can be applied to a broader range of metal oxides compared to silane chemistry, making phosphonate chemistry applicable to a wider variety of surfaces. Secondly, phosphonic acid-based monolayers are less sensitive to moisture than organosilanes. This characteristic is important for practical use such as storage, because the stability of a monolayer is less affected by the humidity of the environment. Furthermore, phosphonate chemistry is less prone to self-condensation. In other words, phosphonic-acid-based reagents should minimize the amount of undesirable byproducts compared to organosilanes, leading to more predictable and controllable biofunctionalization processes [29]. In particular, Li et al. [79] submerged In2O3 nanowire into 3-phosphonopropionic acid, resulting in binding of the phosphonic acid into the surface of the semiconductor. Next, the carboxylic group was activated by carbodiimide chemistry, which served as the anchor for amine-containing probe such as monoclonal antibody (Fig. 6d). Real-time detection in solution has also been demonstrated for analyte down to 5 ng/mL.

In terms of carbon nanotube channel, the surface can be functionalized with 1-pyrenebutyric acid (PBA). PBA contains a pyrene group that can be attached to carbon nanotube via π-π* stacking, while the carboxyl group can be used to covalently anchor to amine-containing probe using carbodiimide chemistry, which typically involves EDC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride) /NHS (N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide) coupling reaction, Fig. 6e. During this coupling process, the EDC creates a reactive O-acylisourea ester, rendering the surface temporarily unstable. This O-acylisourea ester then reacts with the NHS to form an amine-reactive NHS ester, while the surface remains semi-stable. Next, amine group from probe reacts with the amine-reactive NHS ester to form a stable amide bond that immobilizes the probe onto the NHS present on the surface of carbon nanotubes. Filipiak et al. [80] employed this strategy to functionalize SWCNT-FET with nanobody receptor such that the device can detect antigen with high selectivity and sub-picomolar detection limit with a dynamic range exceeding 5 orders of magnitude. Long-term stability measurements reveal a low drift of SWCNTs of 0.05 mV/h, making it promising for continuous real-time monitoring of biomarkers.

Similarly, for graphene semiconductors, the central macrocycle of Tetrakis (4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (TCPP) can be attached to the graphene’s honeycomb carbon network via π-π* stacking. Subsequently, amine-containing probe could be immobilized via EDC/NHS coupling to the carboxyl groups surrounding the macrocycle of TCPP (Fig. 6f). Zhang et al. [81], for example, used this approach to functionalize a GFET with a cortisol aptamer for salivary cortisol tests. Notably, this TCPP decoration not only enhances the sensitivity of liquid gate-GFETs to cortisol but also shields the oxygen-containing groups, thereby reducing any response to pH variations in the samples [81].

Alternatively, a graphene channel can be biochemically functionalized by using 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (PBSE). PBSE contains a pyrene group that interacts with graphene through π-π stacking, at the other end, it has an ester group that reacts with primary amines. Next, a probe containing NH2 can be directly linked to the PBSE by forming amide bonds without EDC/NHS chemistry (Fig. 6g). Zhuang Hao et al. [82] followed this approach to functionalize a GFET involving an aptamer to monitor insulin. Initially, the sensor was submerged in a PBSE solution. It was then washed with dimethylformamide (DMF) to eliminate any unbound PBSE. Next, the device was rinsed with PBS and exposed to an aptamer solution. After PBS rinsing, ethanolamine was applied to the graphene channel to deactivate and block any excess reactive groups left on the graphene surface. The authors, later on, continued with this procedure for the immobilization of IL-6 aptamer to monitor cytokine level in saliva [83].

Another technique for activating the surface of graphene channel with a carboxylate group is utilizing ultraviolet ozone (UVO). However, prolonged exposure to UVO can excessively degrade the graphene's resistance, so UVO exposure is typically limited to two minutes [2]. Once UVO has been applied, amine-containing probe can be immobilized through an EDC/NHS coupling reaction, Fig. 6h. In particular, Ku et al. [2] used this method to functionalize a GFET platform with cortisol monoclonal antibody. The platform was able to measure cortisol concentrations in real time with a detection limit of 10 pg/mL.

Gate surface functionalization techniques

Using a gate as an active layer is another common approach for FETs. In some cases, the surface of the gate electrode is functionalized with probes.

For example, thiol-containing probes such as antibodies and aptamers can readily be used to functionalize top-gate gold electrodes through strong S–Au covalent binding to detect proteins [84], Fig. 7a. Proteins binding to these functionalized electrodes result in a drop in gate voltage, which redistributes the charge density locally around the gate. This induces a change in charge density of the active channel. More importantly, this detection method does not require any dilution or washing processes to reduce ionic strength, yet it remains highly sensitive. The entire detection process only takes about 5 min.

a Surface functionalization/immobilization on top-gate gold electrode with antibody via thiol-gold adsorption (reprinted with permission from Ref. [84] Copyright 2017 Springer Nature). b Cross-sectional view of the 3D-EMG-ISFET sensor functionalized with ion selective membranes sensing (reprinted with permission from Ref. [1] Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society). c Schematic of enzyme immobilization on indium tin oxide films on flexible polyethylene terephthalate substrates (reprinted with permission from Ref [38. Copyright 2013 Elsevier). d Antibody-Embedded polymer coupled to extended gate (reprinted with permission from Ref. [85] Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society)

Zhang et al. [1] introduced a Three-Dimensional Electrode-Metal-Gate Ion-Sensitive FET (3D-EMG-ISFET) for monitoring electrolytes in sweat, Fig. 7b. An efficient functionalization material for electrolyte-sensing is the ion-selective membrane (ISM). ISM has specific embedded ion receptor, known as an ionophore, in a polyvinyl chloride-based membrane ((PVC)/bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS)). This membrane is drop-casted onto the top of the 3D-EMG-ISFET sensing dielectric. The ionophore in the membrane interacts poorly with interfering ions while selectively interacting with target ion. Through these interactions, a junction potential is created, which changes the gate bias of ISFETs and is directly correlated with the ion activity at the liquid-to-ISM interface. In this particular study, three types of membranes were deposited for sensing, resulting in the creation of 3D-EMG-(Na+, K+, Ca2+) sensitive FETs [1].

Yang et al. [38] developed indium tin oxide (ITO) films on flexible polyethylene terephthalate substrates using different NH3 plasma treatment conditions. These ITO films serve as sensing electrodes for extended-gate FETs, Fig. 7c. An NH3 plasma treatment was then introduced to create amine groups on the ITO sensing membranes; thus, offering a simpler alternative to the complex procedures of inducing covalent bonding. Following the NH3 plasma treatment, a glutaraldehyde solution and urease were dripped separately onto the ITO membrane for further functionalization.

An alternative approach involves embedding the probe within a polymer, which is then coupled to the extended gate. Along these lines, Jang et al. [85] used an antibody-embedded PSMA sensing gate to detect cortisol, Fig. 7d. Incorporating the receptor into the polymer structure helped to bind the cortisol molecules in proximity to the membrane-substrate interface, effectively overcoming the problems associated with the Debye length (λD). The reported LOD was 1 pg/mL in phosphate buffer saline, where λD is 0.2 nm.

Probe

Enzyme (EnFET)

Enzyme-modified FET operates based on enzymatic reaction, where the enzyme catalyzes the conversion of a substrate into its product. This enzymatic reaction occurs within the enzyme membrane, leading to the change in accumulated charged carriers on the gate surface, directly proportional to the amount of analyte present in the sample [86]. As a result, protons are either generated or consumed, coupled with a change in pH levels. This change in pH can be measured using a pH-electrode as a reference electrode [87]. Therefore, EnFET biosensors can quantify the presence of the target analyte by correlating the changes in pH with the concentration of the analyte.

For instance, Guo et al. [32] used glucose oxidase (GOD) as the bio-enzyme for creating a MoS2 FET-based serpentine mesh sensor system to detect glucose on artificial eyeballs. To enhance glucose recognition and improve conductance, the team employed a large contact area with tear fluid to absorb and immobilize the enzyme. Initially, GOD (β-D-glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger) is immobilized onto the surface of MoS2 [88, 89], Fig. 8a. The subsequent charge transfer mechanism occurs because the glucose is oxidized by the GOD to form H2O2, which then reacts with oxygen, generating hydrogen ions (H+) and electrons (e−):

a Illustration of the sensing mechanism of the device with oxidation of glucose (reprinted with permission from Ref. [32] Copyright 2021 Elsevier). b Tyrosine sensing mechanism of organic electrochemical transistor functionalized with laccase (reprinted with permission from Ref. [94] Copyright 2017 Elsevier). c Lactate detection with extended-gate organic FET functionalized with lactate oxidase and osmium-redox polymer (reprinted with permission from Ref. [95] Copyright 2019 Springer Nature)

This reaction generates free electrons, leading to an increase in device current due to the behavior of the n-type FET. GOD has a demonstrated high selectivity for glucose, with fully or quasi-reversible glucose conversion. Moreover, it is readily obtainable and has been proven to withstand conditions of extreme pH, ionic strength, and temperature [90,91,92]. This serpentine mesh sensor device can be placed directly onto the lenses for direct contact with tears, in contrast to conventional sensors and circuit chips embedded within the lens substrate. This design offered high detection sensitivity, mechanical robustness, and does not interfere with blinking or vision. Additionally, in-vitro cytotoxicity tests have shown good biocompatibility, making it a promising candidate for the next-generation of soft electronics in healthcare applications.

In a similar study, Kim et al. [93] developed a wearable contact lens capable of selectively and sensitively detecting glucose. To achieve this, the authors immobilized GOD on a graphene channel using a pyrene linker through π-π stacking interactions. GOD is attached to pyrene linker by forming an amide bond resulting from the nucleophilic substitution of N-hydroxysuccinimide. In their experiments, the authors demonstrated in-vivo glucose detection capability on a rabbit eye in real-time as well as wireless in-vitro monitoring of the intraocular pressure of a bovine eyeball. This innovative wearable contact lens holds significant potential for biomedical applications.

Moreover, Battista et al. [94] presented a textile wearable organic electrochemical transistor where the semiconducting polymer was fabricated on cotton fibers (the yarn). Recombinant fungal POXA1b laccase was immobilized by surface adsorption to detect Tyrosine (L-Tyr) (Fig. 8b). Lactate is a class of enzyme catalyzing the single-electron oxidation of phenolic compounds with associated four-electron reduction of oxygen to water. This direct electron transfer without mediator allows for the sensitive detection of Tyrosine in aqueous solutions. This approach allows for detecting Lactate with an LOD of 10 nM, making it a promising extensive utilization in sports, healthcare, and working safety.

Similarly, Minamiki et al. [95] developed an organic field-effect transistors using extended-gate electrode modified with a lactate oxidase on an osmium-redox polymer [69], Fig. 8c. The biosensing capability of the OFET is investigated through real-time measurement of lactate concentration in an aqueous environment. The results showed a limit of detection of 10 mM for sweat, which falls within the range of lactate levels typically found in sweat. In another example, Joshi et al. [96] introduced a novel glucose/lactate FET sensing platform by immobilizing enzymes on a polyimide substrate [97]. In this approach, semiconductor material was made from carbon nanotubes, which randomly sprayed onto a Kapton membrane [98]. The drain current (IDS) for the p-type CNTFET increased as the concentration of lactate or glucose rised [99]. The devices exhibited good shelf life and the ability to withstand repetitive mechanical deformations, making it promising for non-invasive monitoring of biomarkers on wearable devices.

Antibody and nanobody (immunoFET)

Antibodies are essential protective proteins secreted by B-lymphocytes. They are characterized by their “Y” shape and play a crucial role in the immune response of mammals. Furthermore, Antibodies exhibit a remarkable ability to bind to specific antigens with high selectivity, making them valuable for detecting target-specific analytes/antigens [93,94,95]. The recognition between antibodies and antigens will generate an electric field as they are both charged molecules. This electric field alters the flow of carrier between the source and the gate, creating a signal that can be detected electrically [100, 101]. Therefore, the concentration of the analyte can be measured through changes in conductivity resulting from the interaction of antigen–antibody bonds [102], making it promising for clinical diagnosis applications. However, antibodies still have limitations due to its reach over Debye length (λD), which can lead to decreased sensitivity. Jang et al. [85] made significant advancements in overcoming the issue of λD by fabricating FET- based sensor using antibody- embedded poly (styrene-co-methacrylic acid) (PSMA) sensing gate to detect cortisol, Fig. 9a. The embedded structure of the receptor in the polymer allowed cortisol molecules to bind near the membrane-substrate interface, effectively overcome the constraints posed by λD. The authors compared its sensing efficacy with the traditional approach of antibody functionalization on the PSMA surface. With the aim of evaluating the performance of PSMA integrated with embedded antibodies. The antibody-embedded PSMA achieved a limit of detection (LOD) of 1 ng/mL in slightly buffered artificial sweat, demonstrating the potential to overcome the limitation imposed by λD. The effectiveness of antibody-embedded PSMA was subsequently verified through a sandwich ELISA. This study is the first demonstration of FET-based cortisol sensing, where cortisol is electrically detected using polymers on a remote flexible gate platform. This creates opportunities for the detection of cortisol in saliva or sweat within a clinical setting.

a Presumed schematic image of cortisol antibody-embedded geometric in the PSMA polymer matrix (reprinted with permission from Ref. [85] Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society). b Schematic image of the graphene FET device functionalized with cortisol antibody on the surface of graphene channel (reprinted with permission from Ref. [2] Copyright 2020 American Association for the Advancement of Science). c Representative carbon nanotube FET functionalized with nanobody (reprinted with permission from Ref [80] Copyright 2018 Elsevier)

Similarly, Chu et al. [103] developed a new type of FET biosensor using monoclonal antibodies (anti-CEA and anti-NT-pro BNP) to directly detect proteins beyond the discernable Debye length. Protein CEA was effectively detected by using antibodies immobilized on high-electron-mobility transistors (HEMTs). Initially, 2-Mercaptoethylamine (MEA) was utilized to break the disulfide bond in the heavy chain of the IgG antibody. The resulting cleaved thiol group then attached to the gold surface, aligning the antibody with a specific orientation. This coupling exposed the binding site upwards and reduced the distance between the binding and the gate electrode [84]. This approach managed to counteract the significant charge-screening effect caused by the high ionic strength in the solution. Because sensing is not dependent on charge of target proteins, it can detect both charged and neutral proteins. More importantly, this process does not require dilution or washing, making it simpler and more efficient. The practical approaches including evaluating designs, measurement methodologies, and the working mechanism of enzyme FET promise direct protein detection in diagnostics.

Ku et al.[2] fabricated GFET biosensors for cortisol detection by using monoclonal antibody (C-Mab) chemically bonded to the surface of graphene. Figure 9b depicts FET biosensors integrated with contact lenses to noninvasively monitor tears in real time. In their study, graphene serves as a transducer to turn the antibody-cortisol interaction into electrical signals. This approach was able to detect cortisol with an LOD of 10 pg/ml, which is within the typical range of human tear’s cortisol level from 1 to 40 ng/ml [104].

More recently, a novel approach to immunoFETs has emerged, where nanobodies are used to overcome the limitations of the Debye length (λD). Nanobodies are stable and easily producible biological probes, characterized by their remarkably short length of less than 3 nm, which sets them apart from typical antibodies (15 nm) and even antibody fragments (7–8 nm). Their short length means these nanobodies can support analyte binding in proximities much closer to the surface of the sensor. Moreover, nanobodies exhibit impressive physicochemical stability under diverse conditions. As a result, researchers have integrated nanobody receptors into carbon nanotube transistors, giving rise to highly sensitive, selective, and label-free protein detection in physiological solutions [105]. Even though nanobodies possess distinct attributes, they have not been widely employed as probes in FET-based biosensors [106]. Among the few to use them, Filipiak et al. [80] proposed a novel surface modification approach to develop FET sensor by using a very short nanobody receptors combined with a polyethylene glycol layer to overcome the issue of the Debye length, Fig. 9c. Nanomaterial-based FETs with green fluorescent protein was used as the model antigen. FET sensors after being functionalized exhibited exceptional efficiency, sensitive, selective, and label-free protein detection across a wide range of concentrations. This capability remains consistent even in physiological solutions with a high ionic strength (100 mM).

Aptamer

Aptamers are short single-stranded oligo-nucleotide sequences of 15–40 nucleotides in length that have been engineered through a selection process to exhibit an exceptional binding affinity in a manner similar to antibodies and nanobodies [107]. One of the key advantages of aptamers is their small size, which is approximately one-tenth that of an antibody. This makes them potentially ideal for overcoming the Debye length limit when they interact with the target, enhancing sensitivity and lower detection limits, Fig. 10.

Aptamers offer several superior advantages over antibodies as catch probes. First, they are synthesized in vitro, reducing the variation between batches. Furthermore, aptamers can be designed to display varying degrees of affinity for a targeted molecule [108, 109]. Moreover, they demonstrate greater resilience to temperature fluctuations and remain stable during long-term storage [110, 111]. Furthermore, aptamers can be covalently immobilized on most surfaces by modifying either the 5′- or 3′-end [112].

Aptamers provide an additional advantage to apta-FET compared to immuno-FET. Unlike traditional bio-FETs that require target molecules to be charged, aptasensors can accommodate electroneutral targets through conformational changes in the aptamer's negatively charged phosphodiester backbones near the semiconductor channel surface. Target binding induces a secondary conformational shift, causing the aptamer to adopt a more compact structure that positions the negative charges closer to the semiconductor surface, resulting in a negative top gating effect on the device [113].

While the sensing mechanism of aptamer-FETs hinges on altering aptamer conformations due to target-induced surface charge redistribution (aptaswitch), gate voltage manipulation can also influence aptamer configurations [32]. This allows for the modulation of aptamer states to release targets and to achieve effective biosensor regeneration for continuous analyte monitoring. [114, 183]. By implementing standardization, researchers and developers can improve the consistency, comparability, and reliability of FET biosensors to advance practical applications in a range of fields.

Another challenge with epidermal electronics is that they typically involve complicated data processing circuits and need to communicate wirelessly, which are both difficult to implement [183]. One promising solution on the horizon are microwave sensors, which are based on changes in the electromagnetic properties of the sensing materials at ultrahigh frequencies (ca. > 1 GHz). Furthermore, novel bioenergy solutions are essential to transition from conventional laboratory-based sensing to efficient wearable biosensing. These may include self-powered wearable biosensing systems integrated with biofuel cells or battery-free options utilizing NFC technology [13].

Biological challenges

There are several challenges associated with analyzing biofluid with a small volume, which tends to evaporate quickly. Furthermore, there is a great risk of contamination, particularly when saliva is involved and may be mixed with food or drink residues. Additionally, the variability in collection time poses a challenge [9]. To address these issues, microfluidic systems have emerged, which not only offer precise control over sample manipulation but also reducing evaporation. Furthermore, incorporating permselective protective sensor coatings can help prevent the presence of macromolecules on the sensor surface.

Tear, saliva, sweat, interstitial fluids typically have lower concentrations of analytes than in blood samples, thereby requiring ultrasensitive biosensors to ensure accurate detection. It is also crucial to consider the biocompatibility of materials incorporated in these biosensors, particularly when dealing with tear and saliva samples, to ensure their safety for use in the human body. Finally, it may be necessary to undertake a comprehensive study involving a large number of clinical samples to validate the results in non-traditional fluids [184].

Challenges in system integration and hardware

The development and implementation of wearable FET biosensor devices involves integrating various components, including sensors, signal processors, data transmitters, and some form of power management, with the ultimate goal of enabling non-invasive, continuous, and accurate monitoring of biochemical markers in biofluids. Several approaches have been taken to build reliable, comfortable, and user-friendly wearable biosensor systems, such as flexible printed circuit boards, stretchable interconnects, wireless communication modules, and energy harvesting or storage devices [24]. However, there are several challenges and trade-offs that need to be addressed to achieve the desired reliability, comfort, and user-friendliness of wearable biosensor systems. First, a balance is needed between the size, weight, power consumption, and performance of the device components. This involves optimizing the design and selecting the components to ensure an optimal balance between these factors. Second, ensuring the biocompatibility and durability of the materials and sensors used in wearable biosensor systems is crucial. The materials should be compatible with the human body to prevent any adverse reactions, while also being durable enough to withstand everyday use and potential environmental factors. Third, maintaining the stability and accuracy of biosensing signals in different environmental and physiological conditions is a challenge. Wearable biosensor systems should be able to provide reliable measurements regardless of variations in temperature, humidity, motion, and other factors that may affect the signals. Lastly, ensuring the security and privacy of the data transmission and processing is of the utmost importance. Wearable biosensor systems should incorporate robust encryption and authentication measures to safeguard the transmitted data and protect the user's privacy [184].

Challenges in device stretchability

When it comes to develo** wearable biosensors, a key aspect to consider is the mechanical mismatch between rigid active materials and soft human tissues/skin. Lyu et al. [12, 13] have provided a comprehensive review on soft wearable devices, highlighting two main strategies for achieving stretchable devices: deformable architectures and intrinsically stretchable materials. Deformable architectures involve designing structures that can deform or buckle under strain. Some examples of deformable architectures include buckling, microbelts, serpentine, holey, nanomesh, and kirigami. These designs allow the device to stretch and conform to the shape of the human body. On the other hand, intrinsically stretchable materials are materials that possess inherent stretchability. Commonly used stretchable materials for wearable devices include PDMS (polydimethylsiloxane), eco-flex, polyurethane, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), and polyimide. Leveraging deformable architectures and intrinsically stretchable materials, researchers and engineers can develop wearable biosensors that are flexible, comfortable to wear, and capable of accurately monitoring various physiological parameters.

Commercialization challenges and opportunities

Commercial sensors are expected to meet a range of demands, including sensitivity, reliability, scalability, affordability, data security, and real-time communication capability [24]. These factors are essential for the successful adoption and commercialization of sensors across various industries. In addition, future prospects of wearable FET biosensor devices in terms of commercialization depends on the existing products and companies involved in their development. It plays a significant role in advancing wearable FET biosensor technologies and translating them into commercial markets. Regulatory approval is a crucial hurdle that must be overcome to ensure compliance with relevant regulations and standards. Clinical validation is also critical to demonstrate the accuracy and effectiveness of wearable FET biosensors in clinical settings, and to gain acceptance from healthcare professionals and regulatory bodies. User acceptance is another important consideration, as wearable FET biosensors should be designed with user-friendly interfaces and comfortable form factors to promote engagement and adherence to monitoring protocols. Effective data management strategies are necessary to handle the substantial volume of data generated by wearable FET biosensors, while at the same time ensuring data privacy, integrity, and accessibility. Moreover, the wearable biosensor market is highly competitive. Companies need to differentiate themselves through unique features, superior performance, and competitive pricing to gain a foothold and thrive in the market. In conclusion, wearable biosensors hold great potential to revolutionize healthcare and wellness [24]. However, their successful integration and widespread adoption necessitate multidisciplinary collaboration and innovation to overcome technical, clinical, and commercial barriers. By addressing these challenges and leveraging emerging opportunities, wearable FET biosensors can drive transformative advancements in healthcare, contributing to improved patient outcomes and overall well-being.

Perspective and conclusion

Wearable field-effect transistor (FET) biosensors represent a promising avenue for the future of healthcare monitoring. Our comprehensive review examined the recent progress made in FET sensor technology and explored its potential applications in diagnostics. By enabling non-invasive monitoring biomarkers in sweat, tears, saliva, and interstitial fluid, these devices provide real-time health insights that are easy to access, reliable, and cost-effective. Over time, these devices have been developed with various technologies including gating, material enhancements, semiconductor layers, and functionalization methods. These innovations have improved sensor sensitivity, reduced detection limits, and expanded the range of conditions they can address. We also present fabrication techniques as well as sensing probes including enzyme, antibody/nanobody, aptamer and ion-selective membrane. The ongoing development of continuous and non-invasive health monitoring holds the promise of increased accessibility and usability for individuals, with heightened accuracy, available anytime and anywhere.

Despite their numerous advantages and the corresponding potential, current research studies largely remain confined to laboratory settings. However, there is an expectation that these developments will eventually transition into practical applications. We anticipate that with further development and refinement, these biosensors will become integral parts of our daily lives. As these devices become more user-friendly and accessible, individuals will have the power to monitor their health continuously, enabling early detection of health issues and timely interventions. In the near future, the advances in novel probe technologies such as aptamers and nanobodies holds the promise of detection of diverse diseases with improved sensitivity and detection limits. Moreover, the integration of multifunctional FET biosensors with predictive machine learning technologies such as time-series analytics [185,186,187], has the potential to elevate sensing capabilities. This integration will not only improve the accuracy and timeliness of disease assessments but also enable personalized health predictions. Additionally, the seamless integration of electronics components such as amplifier and analog/digital coverter links sensors with wireless devices such as wristwatches, smartphones, iPads and laptops. This integration will result in a more user-friendly and intuitive interface, allowing users to effortlessly access and interpret their health data. In this regard, addressing ethical and privacy concerns will be paramount. Striking the right balance between data collection and individual privacy is a challenge that needs ongoing attention. Researchers, policymakers, and technology companies must collaborate to establish clear guidelines and standards for data security and privacy in the context of wearable health monitoring.

In conclusion, wearable FET biosensors have the potential to revolutionize healthcare and wellness by providing real-time, non-invasive monitoring of biomarkers. Addressing the challenges discussed here through multidisciplinary collaboration will be key to achieve this goal.

Fundings

T.T.H. Nguyen acknowledges funding from Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering. N.T. Nguyen and M.A. Huynh acknowledge funding from Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project (DP220100261) and Laureate Fellowship (FL230100023). T.K. Nguyen acknowledges funding from Griffith University Postdoctoral Fellowship and DE240100408. M.C.N acknowledges funding from Griffith University Higher Degree Research Scholarship.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Zhang J, et al. Sweat biomarker sensor incorporating picowatt, three-dimensional extended metal gate ion sensitive field effect transistors. Acs Sensors. 2019;4(8):2039–47.

Ku M, et al. Smart, soft contact lens for wireless immunosensing of cortisol. Science Adv. 2020;6(28):eabb2891.

Yu Y, et al. Proteomic and peptidomic analysis of human sweat with emphasis on proteolysis. J Proteomics. 2017;155:40–8.

Delgado-Povedano MM, et al. Metabolomics analysis of human sweat collected after moderate exercise. Talanta. 2018;177:47–65.

Katchman BA, et al. Eccrine Sweat as a biofluid for profiling immune biomarkers. Proteom Clin Appl. 2018;12(6):1800010.

Orro K, et al. Development of TAP, a non-invasive test for qualitative and quantitative measurements of biomarkers from the skin surface. Biomarker Research. 2014;2(1):20.

Yu Y, et al. Flexible electrochemical bioelectronics: the rise of in situ bioanalysis. Adv Mater. 2020;32(15):1902083.

Arduini F, et al. Electrochemical biosensors based on nanomodified screen-printed electrodes: recent applications in clinical analysis. TrAC, Trends Anal Chem. 2016;79:114–26.

Kim J, et al. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(4):389–406.

Villena Gonzales W, Mobashsher AT, Abbosh A. The progress of glucose monitoring—a review of invasive to minimally and non-invasive techniques, devices and sensors. Sensors. 2019;19(4):800.

Syahir A, et al. Label and label-free detection techniques for protein microarrays. Microarrays. 2015;4(2):228–44.

Lyu Q, et al. Soft wearable healthcare materials and devices. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2021;10(17):2100577.

Lyu Q, et al. Soft, disruptive and wearable electrochemical biosensors. Curr Anal Chem. 2022;18(6):689–704.

Caras S, Janata J. Field effect transistor sensitive to penicillin. Anal Chem. 1980;52(12):1935–7.

Mao S, et al. Two-dimensional nanomaterial-based field-effect transistors for chemical and biological sensing. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(22):6872–904.

Wang Z, et al. An ultraflexible and stretchable aptameric graphene nanosensor for biomarker detection and monitoring. Adv Func Mater. 2019;29(44):1905202.

Wang B, et al. Wearable aptamer-field-effect transistor sensing system for noninvasive cortisol monitoring. Sci Adv. 2022;8(1):eabk0967.

Liu Q, et al. Flexible multiplexed In2O3 nanoribbon aptamer-field-effect transistors for biosensing. Iscience. 2020;23(9):101469.

Garcia-Cordero E, et al. Three-dimensional integrated ultra-low-volume passive microfluidics with ion-sensitive field-effect transistors for multiparameter wearable sweat analyzers. ACS Nano. 2018;12(12):12646–56.

Kim HM, et al. Metal–insulator–semiconductor coaxial microfibers based on self-organization of organic semiconductor: polymer blend for weavable, fibriform organic field-effect transistors. Adv Func Mater. 2016;26(16):2706–14.

Bao C, Kaur M, Kim WS. Toward a highly selective artificial saliva sensor using printed hybrid field effect transistors. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2019;285:186–92.

Li M-Z, Han S-T, Zhou Y. Recent advances in flexible field-effect transistors toward wearable sensors. Adv Intell Syst. 2020;2(11):2000113.

Chen S, et al. Review on two-dimensional material-based field-effect transistor biosensors: accomplishments, mechanisms, and perspectives. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):1–32.

Dai C, Liu Y, Wei D. Two-dimensional field-effect transistor sensors: the road toward commercialization. Chem Rev. 2022;122(11):10319–92.

Lussem B, et al. Doped organic transistors. Chem Rev. 2016;116(22):13714–51.

Ren Y, et al. Gate-tunable synaptic plasticity through controlled polarity of charge trap** in fullerene composites. Adv Func Mater. 2018;28(50):1805599.

Vu C-A, Chen W-Y. Field-effect transistor biosensors for biomedical applications: recent advances and future prospects. Sensors. 2019;19(19):4214.

Russel WB, et al. Colloidal dispersions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

Gao Q, et al. Applications of transistor-based biochemical sensors. Biosensors. 2023;13(4):469.

Chao L, et al. Recent advances in field effect transistor biosensor technology for cancer detection: a mini review. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2021;55(15): 153001.

Chu C, H Sarangadharan I, Regmi A, Chen YW, Hsu C‐P, Chang W‐H, Lee G‐Y, Chyi J‐I, Chen C‐C, Shiesh S‐C, Lee G‐B., Wang Y‐L, Sci. Rep, 2017. 7: p. 5256.

Guo S, et al. Integrated contact lens sensor system based on multifunctional ultrathin MoS2 transistors. Matter. 2021;4(3):969–85.

Liu Q, et al. Flexible multiplexed In2O3 nanoribbon aptamer-field-effect transistors for biosensing. Iscience. 2020;23(9): 101469.

Go J, Nair PR, Alam MA. Theory of signal and noise in double-gated nanoscale electronic pH sensors. J Appl Phys. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4737604.

Capua L, et al. Label-free C-reactive protein Si nanowire FET sensor arrays with super-Nernstian back-gate operation. IEEE Trans Electron Devices. 2022;69(4):2159–65.

Liang Y, et al. Wafer-scale uniform carbon nanotube transistors for ultrasensitive and label-free detection of disease biomarkers. ACS Nano. 2020;14(7):8866–74.

Chi L-L, et al. Study on extended gate field effect transistor with tin oxide sensing membrane. Mater Chem Phys. 2000;63(1):19–23.

Yang C-M, et al. Low cost and flexible electrodes with NH3 plasma treatments in extended gate field effect transistors for urea detection. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2013;187:274–9.

Liu Y, et al. A novel AlGaN/GaN heterostructure field-effect transistor based on open-gate technology. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22431.

Ohshiro K, et al. Oxytocin detection at ppt level in human saliva by an extended-gate-type organic field-effect transistor. Analyst. 2022;147(6):1055–9.

Petrelli M, et al. Flexible, planar, and stable electrolyte-gated carbon nanotube field-effect transistor-based sensor for ammonium detection in sweat. in 2022 IEEE International Flexible Electronics Technology Conference (IFETC). 2022. IEEE.

Chen Y, et al. Field-effect transistor biosensors with two-dimensional black phosphorus nanosheets. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89:505–10.

Amen MT, et al. Metal-oxide FET biosensor for point-of-care testing: overview and perspective. Molecules. 2022;27(22):7952.

Zong X, Z Zhang, and R Zhu. Ultra-miniaturized glucose biosensor using zinc oxide nanorod-based field effect transistor. in 2017 IEEE SENSORS. 2017. IEEE.

Tintelott M, et al. Process variability in top-down fabrication of silicon nanowire-based biosensor arrays. Sensors. 2021;21(15):5153.

Zhang L, Dong J, Ding F. Strategies, status, and challenges in wafer scale single crystalline two-dimensional materials synthesis. Chem Rev. 2021;121(11):6321–72.

Geim AK, Novoselov KS. The rise of graphene. Nat Mater. 2007;6(3):183–91.

Novoselov KS, et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science. 2004;306(5696):666–9.

Huo C, et al. 2D materials via liquid exfoliation: a review on fabrication and applications. Science Bulletin. 2015;60(23):1994–2008.

Das A, et al. Metal oxide nanosheet: synthesis approaches and applications in energy storage devices (batteries, fuel cells, and supercapacitors). Nanomaterials. 2023;13(6):1066.

Zhang Y, et al. Facile exfoliation for high-quality molybdenum disulfide nanoflakes and relevant field-effect transistors developed with thermal treatment. Front Chem. 2021;9: 650901.

Yu H-D, et al. Chemical routes to top-down nanofabrication. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42(14):6006–18.

Smith Jr, J., et al., Dispersion of single wall carbon nanotubes by in situ polymerization under sonication. 2002.

Wang Z, Jia Y. Graphene solution-gated field effect transistor DNA sensor fabricated by liquid exfoliation and double glutaraldehyde cross-linking. Carbon. 2018;130:758–67.

Hernandez Y, et al. High-yield production of graphene by liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3(9):563–8.

Yasaei P, et al. High-quality black phosphorus atomic layers by liquid-phase exfoliation. Adv Mater. 2015;27(11):1887–92.

Brent JR, et al. Production of few-layer phosphorene by liquid exfoliation of black phosphorus. Chem Commun. 2014;50(87):13338–41.

Ho T-W, Hong FC-N. A novel method to grow vertically aligned silicon nanowires on Si (111) and their optical absorption. J Nanomater. 2012;2012:64–64.

Lee S, et al. Oxide-assisted semiconductor nanowire growth. MRS Bull. 1999;24(8):36–42.

Bai F, et al. One-step synthesis of lightly doped porous silicon nanowires in HF/AgNO3/H2O2 solution at room temperature. J Solid State Chem. 2012;196:596–600.

Li H, et al. Epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered transition-metal dichalcogenides: growth mechanism, controllability, and scalability. Chem Rev. 2017;118(13):6134–50.

Li H, et al. A universal, rapid method for clean transfer of nanostructures onto various substrates. ACS Nano. 2014;8(7):6563–70.

Jeffries A, et al. Gallium nitride grown by molecular beam epitaxy at low temperatures. Thin Solid Films. 2017;642:25–30.

Özgür, Ü., V. Avrutin, and H. Morkoç, Zinc oxide materials and devices grown by molecular beam Epitaxy, in Molecular Beam Epitaxy. 2018, Elsevier. p. 343-375

Nakayama Y, Tsuruta R, Koganezawa T. ‘Molecular beam epitaxy’on organic semiconductor single crystals: characterization of well-defined molecular interfaces by synchrotron radiation X-ray diffraction techniques. Materials. 2022;15(20):7119.

Nunn W, Truttmann TK, Jalan B. A review of molecular-beam epitaxy of wide bandgap complex oxide semiconductors. J Mater Res. 2021;36:1–19.

Mackus AJ, Merkx MJ, Kessels WM. From the bottom-up: toward area-selective atomic layer deposition with high selectivity. Chem Mater. 2018;31(1):2–12.

George SM. Atomic layer deposition: an overview. Chem Rev. 2010;110(1):111–31.

Oviroh PO, et al. New development of atomic layer deposition: processes, methods and applications. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2019;20(1):465–96.

Neupane GP, et al. 2D organic semiconductors, the future of green nanotechnology. Nano Mater Sci. 2019;1(4):246–59.

Kafle P, et al. Printing 2D conjugated polymer monolayers and their distinct electronic properties. Adv Func Mater. 2020;30(12):1909787.

Kim JH, et al. Green-sensitive phototransistor based on solution-processed 2D n-type organic single crystal. Adv Electron Mater. 2019;5(10):1900478.

Eswaran M, et al. A road map toward field-effect transistor biosensor technology for early stage cancer detection. Small Methods. 2022;6(10):2200809.

Mello HJNPD, Mulato M. Enzymatically functionalized polyaniline thin films produced with one-step electrochemical immobilization and its application in glucose and urea potentiometric biosensors. Biomed Microdev. 2020;22:1–9.

Sandhyarani N. Surface modification methods for electrochemical biosensors, in Electrochemical biosensors. 2019, Elsevier. p. 45-75

Nair PR, Alam MA. Theory of “Selectivity” of label-free nanobiosensors: a geometro-physical perspective. Journal of applied physics. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3310531.

Hayashi H, et al. Tetrameric jacalin as a receptor for field effect transistor biosensor to detect secretory IgA in human sweat. J Electroanal Chem. 2020;873: 114371.

Ren H, et al. Field-effect transistor-based biosensor for pH sensing and map**. Adv Sensor Res. 2023;2:2200098.

Li C, et al. Complementary detection of prostate-specific antigen using In2O3 nanowires and carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(36):12484–5.

Filipiak MS, et al. Highly sensitive, selective and label-free protein detection in physiological solutions using carbon nanotube transistors with nanobody receptors. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2018;255:1507–16.

Zhang R, Jia Y. A disposable printed liquid gate graphene field effect transistor for a salivary cortisol test. ACS sensors. 2021;6(8):3024–31.

Hao Z, et al. Real-time monitoring of insulin using a graphene field-effect transistor aptameric nanosensor. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(33):27504–11.

Hao Z, et al. Graphene-based fully integrated portable nanosensing system for on-line detection of cytokine biomarkers in saliva. Biosens Bioelectron. 2019;134:16–23.

Chu C-H, et al. Beyond the Debye length in high ionic strength solution: direct protein detection with field-effect transistors (FETs) in human serum. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):5256.

Jang H-J, et al. Electronic cortisol detection using an antibody-embedded polymer coupled to a field-effect transistor. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(19):16233–7.

Nguyen HH, et al. Immobilized enzymes in biosensor applications. Materials. 2019;12(1):121.

Lee C-S, Kim SK, Kim M. Ion-sensitive field-effect transistor for biological sensing. Sensors. 2009;9(9):7111–31.

Shan J, et al. High sensitivity glucose detection at extremely low concentrations using a MoS 2-based field-effect transistor. RSC Adv. 2018;8(15):7942–8.

Wu S, et al. High visible light sensitive MoS2 ultrathin nanosheets for photoelectrochemical biosensing. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;92:646–53.

Bankar SB, et al. Glucose oxidase—an overview. Biotechnol Adv. 2009;27(4):489–501.

Sha R, Bhattacharyya TK. MoS2-based nanosensors in biomedical and environmental monitoring applications. Electrochim Acta. 2020;349: 136370.

Bobrowski T, Schuhmann W. Long-term implantable glucose biosensors. Curr Opin Electrochem. 2018;10:112–9.

Kim J, et al. Wearable smart sensor systems integrated on soft contact lenses for wireless ocular diagnostics. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14997.

Battista E, et al. Enzymatic sensing with laccase-functionalized textile organic biosensors. Org Electron. 2017;40:51–7.

Minamiki T, Tokito S, Menami T. Fabrication of a flexible biosensor based on an organic field-effect transistor for lactate detection. Anal Sci. 2019;35(1):103–6.

Joshi S, et al. Flexible lactate and glucose sensors using electrolyte-gated carbon nanotube field effect transistor for non-invasive real-time monitoring. IEEE Sens J. 2017;17(14):4315–21.

Boero C, et al. Highly sensitive carbon nanotube-based sensing for lactate and glucose monitoring in cell culture. IEEE Trans Nanobiosci. 2011;10(1):59–67.

Abdelhalim A, et al. Fabrication of carbon nanotube thin films on flexible substrates by spray deposition and transfer printing. Carbon. 2013;61:72–9.

Yoon H, Ko S, Jang J. Field-effect-transistor sensor based on enzyme-functionalized polypyrrole nanotubes for glucose detection. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112(32):9992–7.

Yin PT, et al. Prospects for graphene–nanoparticle-based hybrid sensors. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2013;15(31):12785–99.

Pumera M. Graphene in biosensing. Mater Today. 2011;14(7–8):308–15.

Ramnani P, Saucedo NM, Mulchandani A. Carbon nanomaterial-based electrochemical biosensors for label-free sensing of environmental pollutants. Chemosphere. 2016;143:85–98.