Abstract

Background

Elevated serum uric acid is commonly associated with high triglyceride. However, the relation of triglyceride and hyperuricemia in different gender and age groups is currently not well understood. This study aimed to evaluate age- and gender-related association of high triglyceride with hyperuricemia in a subgroup of Chinese population.

Methods

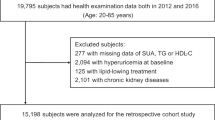

We retrospectively analyzed physical examination data of 24,438 subjects (12,557 men and 11,881 women) in Kaifeng, China. The alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride and serum uric acid were measured in all subjects. The triglyceride was categorized into < 1.21, 1.21 ~, 1.7 ~, 2.83 ~ and > 5.6 mmol/L subgroups, and odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of hyperuricemia were calculated by logistic regression analysis.

Results

Univariate and age-adjusted analyses showed that high triglyceride was positively associated with hyperuricemia (p < 0.01). Further age-stratified analysis showed that the positive association was significant in the 20 ~, 30 ~, 40 ~, 50 ~, 60 ~ and 80 ~ age groups in men. In women, no statistically significant was found in 60 ~ and 70 ~ age groups.

Conclusion

High triglyceride is positively associated with hyperuricemia in both men and women, and this association is age-related, especially in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hyperuricemia is widely considered as a key risk factor for metabolic syndrome, including dyslipidemia, in which hypertriglyceridemia is the most common lipid abnormality [1,2,3,4,5,6]. High uric acid (UA) levels were associated with increased triglyceridemia, independently of metabolic syndrome [7]. A survey of the prevalence of obesity in China during 2004 to 2008 showed that all rural areas had a low prevalence of obesity except in Henan, probably because of differences in diet [17]. A Kuwait study further supported the close relation in dyslipidemic patients, a group already at high coronary artery disease risk [18]. Nevertheless, whether age and gender differences mediate the association between serum UA levels and TG is still controversial. In present study, we demonstrated that after adjustment with age (Model 2) and other confounding factors (Model 3), the OR still increased with the increase in TG. These results suggest that TG levels independently affect the incidence of hyperuricemia. However, in multivariate logistic regression analysis, the positive association between hyperuricemia and TG showed a gender and age differences and the positive association was the lowest in the 50~ age group. Whether decreasing level of estrogen after menopause is responsible for the differences needs further studies.

Stelmach et al. investigated 607 Polish adults with hyperuricemia and demonstrated that the upper tertile of serum uric acid levels had higher TG values in males but not in females [19]. In contrast, Lippi et al. retrospectively enrolled a large cohort of unselected adult outpatients and showed that triglycerides were independently associated with serum UA in women but not in men [20]. Notably, in this study our data showed that high TG level was positively associated with the incidence of hyperuricemia in both men and women. This is consistent with a prospective study which demonstrated that hypertriglyceridemia in men might strengthen the effect of serum UA on the development of gout [21]. Chinese diet is characterized with a high-fat diet, particularly the overconsumption of cooking oil may be a significant risk factor for obesity [22, 23].

To investigate lipid abnormalities in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients, Wei et al. retrospectively analyzed 1213 AMI patients in East China and showed a significant difference in triglycerides for male but not for female AMI patients [24]. Xu et al. found that older Chinese people had moderate and high levels of unbalanced diets [25]. Significant differences were influenced by many factors, such as gender, marital status, work status, education levels. These findings highlight complex interaction between hyperuricemia and TG. Differences in dietary patterns such as the proportion of carbohydrate or fat may be responsible for the variability in the relationship between serum uric acid and triglyceridemia.

TyG index is proposed as a marker of moderate insulin resistance. Therefore, we analyzed the association of TyG with hyperuricemia. We found that TyG could be a better index of hyperuricemia in females than in males. However, a recent study indicated that TyG index presented the significant risks for chronic kidney disease in both men and women [26]. The reason for the disparities is unclear and need additional investigations.

Our study has two main limitations. First, our study was conducted in a special group, so the generalizability of our findings to other population needs confirmation in future studies. Second, confounding factors such as diet patterns and health concerns among people of different ages were not included in our analysis, which may have an impact on the results. Further studies are required to elucidate the association between triglyceride and hyperuricemia in different gender and age groups.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that high triglyceride was positively associated with hyperuricemia in both men and women, and this association was age-related, especially in women.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material are available upon request.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SCr:

-

Serum creatinine

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- UA:

-

Uric acid

- γ-GT:

-

γ-glutamyl transpeptidase

References

Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Giovannini M, Grandi E, D'Addato S, Borghi C. Brisighella heart study group. Interaction between low-density lipoprotein-cholesterolaemia, serum uric level and incident hypertension: data from the Brisighella heart study. J Hypertens. 2019;37:728–31.

Cicero AFG, Fogacci F, Giovannini M, Grandi E, Rosticci M, D'Addato S, Borghi C. Serum uric acid predicts incident metabolic syndrome in the elderly in an analysis of the Brisighella heart study. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11529.

Kim HJ, Kim JE, Jung JH, Kim ER, Hong SN, Chang DK, Son HJ, Rhee PL, Kim JJ, Kim YH. Uric acid is a risk Indicator for metabolic syndrome-related colorectal adenoma: results in a Korean population receiving screening colonoscopy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;66:202–8.

Carminati SA, Barbosa MC, Fader CM. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) induces autophagy in osteoblast precursor 3T3-L1. Biocell. 2018;42:13–6.

Zhang X, Meng Q, Feng J, Liao H, Shi R, Shi D, Renqian L, Langtai Z, Diao Y, Chen X. The prevalence of hyperuricemia and its correlates in Ganzi Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17:235.

Pinto X, Corbella E, Valdevielso P, Mostaza J. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in hypertriglyceridaemic patients: higher than it may appear. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:233–4.

Keenan T, Blaha MJ, Nasir K, Silverman MG, Tota-Maharaj R, Carvalho JA, Conceicao RD, Blumenthal RS, Santos RD. Relation of uric acid to serum levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and to hepatic steatosis. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1787–92.

Wang L, Lyu J, Guo Y, Bian Z, Yu C, Zhou H, Tan Y, Pei P, Chen J, Chen Z, Li L. Regional specific differences in prevalence of overweight/obesity in China: findings from China Kadoorie biobank study in 10 areas in China. Zhonghua Liu **ng Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2015;36:1190–4.

Di Angelantonio E, Sarwar N, Perry P, Kaptoge S, Ray KK, Thompson A, Wood AM, Lewington S, Sattar N, Packard CJ, Collins R, Thompson SG, Danesh J. Major lipids, apolipoproteins, and risk of vascular disease. JAMA. 2009;302:1993–2000.

Braga F, Pasqualetti S, Ferraro S, Panteghini M. Hyperuricemia as risk factor for coronary heart disease incidence and mortality in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54:7–15.

Gazi E, Temiz A, Altun B, Barutcu A, Bekler A, Gungor O, Yener AU, Kurt T, Ozcan S, Gazi S. The association between serum uric acid level and heart failure and mortality in the early period of ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2014;42:501–8.

Gandhi PK, Gentry WM, Ma Q, Bottorff MB. Cost-effectiveness analysis of allopurinol versus febuxostat in chronic gout patients: a U.S. payer perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:165–75.

Liou TL, Lin MW, Hsiao LC, Tsai TT, Chan WL, Ho LT, Hwu CM. Is hyperuricemia another facet of the metabolic syndrome? J Chin Med Assoc. 2006;69:104–9.

Baliarsingh S, Sharma N. Serum uric acid level is an indicator of total cholesterol and low density lipoprotein cholesterol in men below 45 years in age but not older males. Clin Lab. 2012;58:545–50.

Feldman EB, Wallace SL. Hypertriglyceridemia in gout. Circulation. 1964;29(SUPPL):508–13.

Berkowitz D. Blood lipid and uric acid interrelationships. JAMA. 1964;190:856–8.

Conen D, Wietlisbach V, Bovet P, Shamlaye C, Riesen W, Paccaud F, Burnier M. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and relation of serum uric acid with cardiovascular risk factors in a develo** country. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:9.

Al-Meshaweh AF, Jafar Y, Asem M, Akanji AO. Determinants of blood uric acid levels in a dyslipidemic Arab population. Med Princ Pract. 2012;21:209–16.

Stelmach MJ, Wasilewska N, Wicklund-Liland LI, Wasilewska A. Blood lipid profile and BMI-Z-score in adolescents with hyperuricemia. Ir J Med Sci. 2015;184:463–8.

Lippi G, Montagnana M, Luca Salvagno G, Targher G, Cesare Guidi G. Epidemiological association between uric acid concentration in plasma, lipoprotein(a), and the traditional lipid profile. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:E76–80.

Chen JH, Pan WH, Hsu CC, Yeh WT, Chuang SY, Chen PY, Chen HC, Chang CT, Huang WL. Impact of obesity and hypertriglyceridemia on gout development with or without hyperuricemia: a prospective study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:133–40.

Astrup A, Dyerberg J, Selleck M, Stender S. Nutrition transition and its relationship to the development of obesity and related chronic diseases. Obes Rev. 2008;9(Suppl 1):48–52.

Hu G, Pekkarinen H, Hanninen O, Tian H, ** R. Comparison of dietary and non-dietary risk factors in overweight and normal-weight Chinese adults. Br J Nutr. 2002;88:91–7.

Wei Y, Qi B, Xu J, Zhou G, Chen S, Ouyang P, Liu S. Age- and sex-related difference in lipid profiles of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction in East China. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:562–7.

Xu X, Hall J, Byles J, Shi Z. Assessing dietary quality of older Chinese people using the Chinese diet balance index (DBI). PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121618.

Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Hamaguchi M, Obora A, Kojima T, Fukui M. Triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor of incident chronic kidney disease: a population-based longitudinal study. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01729-2 [Epub ahead of print].

Acknowledgements

We thank all of participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific and Technological Project of Henan Province (No. 201502017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GC and YL designed the study. LZ, QW, YZ, JX, CY, YM, MX, RH collected the data. YL and XZ analyzed the data. LZ and GC wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Huaihe Hospital of Henan University and all subjected provided written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Wan, Q., Zhou, Y. et al. Age-related and gender-stratified differences in the association between high triglyceride and risk of hyperuricemia. Lipids Health Dis 18, 147 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1077-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-019-1077-5