Abstract

Background

To describe epidemiologists’ experience of team dynamics and leadership during emergency response, and explore the utility of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) tool during future public health emergency responses. The TEAM tool included categories for leadership, teamwork, and task management.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey between October 2019 and February 2020 with the global applied field epidemiology workforce. To validate the TEAM tool for our context, we used exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis.

Results

We analysed 166 completed surveys. Respondents included national and international emergency responders with representation of all WHO regions. We were unable to validate the TEAM tool for use with epidemiology teams involved in emergency response, however descriptive analysis provided insight into epidemiology emergency response team performance. We found female responders were less satisfied with response leadership than male counterparts, and national responders were more satisfied across all survey categories compared to international responders.

Conclusion

Functional teams are a core attribute of effective public health emergency response. Our findings have shown a need for a greater focus on team performance. We recommend development of a fit-for-purpose performance management tool for teams responding to public health emergencies. The importance of building and supporting the development of the national workforce is another important finding of this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated the importance of an effective emergency response epidemiology workforce. Public health emergencies, like COVID-19, are expected to increase in frequency and severity due to factors such as climate change and urbanisation [1]. We must heed this evidence to ensure an optimal response.

The epidemiology emergency response workforce aims to reduce the impact of a crisis on affected populations [2]. The effectiveness of response teams is critical to mitigating this impact. In this study, we consider a team as a group of people who work together to achieve a set outcome, and an effective team as one who collaborates, produces a desired result, and are collectively competent [3, 4]. This study focused on the experience of the epidemiological workforce within multi-disciplinary emergency response teams [5].

Team dynamics underpin team effectiveness. Tuckman’s seminal work on teams identified five stages of a team lifecycle [6]. The initial stage, ‘forming’, is where initial relationships are developed. ‘Storming’ is reported to be a more turbulent stage, where the team challenge each other and can conflict on issues and in team relationships. ‘Norming’ is where the team develop standards, roles, and feel more comfortable sharing opinions. ‘Performing’ is when the team relationships are stable, roles are clear, and the team are able to focus on tasks and solve problems together. Over time, and through these stages, the team learn become more effective until the end of the team lifecycle, ‘Adjourning’ [6].

Team effectiveness is also influenced by team competence and team management. Team competence is established through delineation of clear roles, clarification of expectations, and development of a shared understanding of skills, knowledge, and motivation [7]. Team management in response is hampered by short deployment periods, high staff rotation, limited standardisation of epidemiology training or skills, and challenges associated with leadership and communication [4, 8,9,10,11]. The combined impact of team dynamics, team confidence and team management during emergency response influence the teams effectiveness [12].

Valid and reliable teamwork assessment tools may highlight factors requiring intervention to strengthen individual and team performance. Numerous tools are available to assess teams during a crisis, however, they have largely been developed for clinical settings and are not routinely used during public health emergency response events [13]. A systematic review of teamwork measurement tools during crises compared 13 tools [13]. One of those 13 tools was the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM). The TEAM was originally developed for use in hospitals to evaluate team performance during resuscitation events, and was found to provide valid and reliable team performance assessment with respect to leadership, teamwork, and task management during emergency response in the hospital environment (Table 1) [4]. The generalisability of this tool to alternate emergency response environments has not been assessed [13,14,15,16,17,18]. We selected the TEAM tool for our survey as the ‘elements’ (Table 1) reflected issues raised by our key informant interviewees,[4] and to test the generalisability of the tool in an epidemiology emergency response setting.

Methods

Study design

We developed and distributed a cross sectional survey to investigate epidemiologists’ experience of team dynamics and leadership during emergency responses. This survey was part of a larger study, conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic [4, 5, 8].

Study population

The global applied epidemiology workforce was the target population for this survey. We defined this workforce as any person working in an applied or field epidemiology role or acute public health responder role. For this analysis, we analysed responses of participants who indicated experience in responding to emergencies in an epidemiology role.

Recruitment

We applied purposive and snowballing sampling techniques to identify potential participants [21, 22]. We collaborated with TEPHIConnect, an online platform of international Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) alumni, to distribute our survey to 1700 registered members (September 2019). We ran a social media campaign and advertised the survey at international epidemiology conferences in both English and French over a three-month period, October 2019 – February 2020.

Data collection

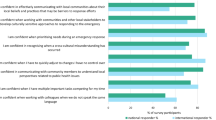

The survey was self-administered online via REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). We selected the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) tool (Table 1) [19] as it aligned with needs identified during key informant interviewees [4]. Questions 1–11 used a Likert scale format with a five-point scale ranging from 0 (never/hardly ever) to 4 (always/nearly always). These questions covered three overarching categories; leadership, teamwork, and task management. The final TEAM question used a scale from 0 to 10 for participants to rate the team’s overall performance [20]. We did not change the wording of the questions, however we made minor wording adjustments to the question prompts to ensure appropriateness to the epidemiologist context. We added one additional open ended question to obtain individual perspectives on team functionality during emergency response. Participants were asked to answer the questions reflecting on their most recent emergency response prior to survey completion.

Data analysis

To calculate the overall score, we used the TEAM tool rating scale [19, 20]. According to the TEAM tool, a total performance score on the first 11 questions of 33 or less was considered “poor”, 34–39 was “good” and 40–44 was “excellent” [19]. In the final question, participants were asked to provide an overall ‘global’ rating of team performance. An overall rating of 8–10 was considered “excellent”, 7 or less was “poor” [19].

We defined those who reported their most recent emergency response within a national setting as ‘national responders’, and those who reported their most recent emergency response within an international setting as ‘international responders’.

Survey data was analysed using Microsoft Excel (2016) and Stata15 (TX:StataCorp). To explore differences between responder types (international or national) and self-identified gender we conducted either the Student t-test or Kruskal–Wallis test depending on the nature of the data, results are shown as t-test. We considered differences significant if they fell outside the 95% confidence interval. Content analysis was used to analyse responses to open-ended questions.

To investigate the usefulness of the TEAM tool for this context, we first conducted an exploratory factor analysis. We measured internal consistency of items using Cronbach’s alpha, where a value of > 0.7 was considered consistent [23,24,25,26]. We then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis assuming three factors. Factor loadings are the correlation between an item and a factor, we considered factor loadings > 0.5 to be interpretable [24].

Consent and ethics

This survey was approved by The Australian National University Human Research Ethics Committee, ID 2019–068.

Results

Demographics

We analysed 166 completed surveys. The median age of respondents was 39 years (range: 23–77 years), and 51% (n = 85/166) identified as female. All World Health Organization (WHO) regions were represented (Table 2).

The survey asked about the respondents’ experience during their most recent emergency response; 96 (59%) reported they had responded within their own country, 66 (41%) had been deployed internationally.

The team emergency assessment measure (TEAM)

The mean overall score in this survey was 32 of a possible 44 (range 0–44), with a standard deviation of 7.4. The mean score for national responders was 34 (range 8–44), and international responders was 29.5 (range 0–44) (p = 0.001) (Table 2).

Comparing the three tool categories, ‘task management’ scored the highest overall rating and ‘leadership’ scored the lowest, however, there was little variation between the final assessment scores (Table 3).

National responders reported statistically higher satisfaction in all survey questions compared to international responders, with the exception of question eight: ‘monitoring and assessing the situation’ (Table 3). No statistical difference was found between epidemiology experience, epidemiology training type, or years of epidemiology experience (data not shown).

Leadership

Participants were asked about the leadership direction and perspective during their last response. The average leadership score across both questions and all respondents was 2.8 of a possible 4. For both leadership questions, respondents of national teams reported statistically significant higher satisfaction on average than those of international teams (p = 0.003). Male respondents rated leadership more highly than females (p = 0.03) (Table 3).

The first question on leadership direction addressed whether team leaders were clear about their direction and command, and whether the team knew what was expected. National responders reported higher satisfaction in leadership direction (p = 0.001). Similarly, male respondents were more satisfied with leadership direction and command (p = 0.005) (Table 3).

The second leadership question asked whether the team leader maintained a ‘global perspective’. National responders reported higher satisfaction with leadership perspective than international responders (p = 0.05) (Table 3).

In free text responses, respondents reported needing more leadership training. Respondents indicated that people with strong technical skills were often placed in positions of leadership, but had limited skills in this role. “It is critical for the team leader to have operational and logistics training and experience. It's not always about the science, but surviving the environment around the science.”

Gaps in leadership during response were frequently reported where team members needed to unofficially step up into the role. “We did not have a lead epi[demiologist] the entire time I was there. So the epi[demiology] team just managed ourselves together” and “we had a very poor leader, however, the team was very strong and had worked through similar outbreak responses together so there were pseudo-leaders who were able to step up and lead the team.”

Teamwork

Participants were asked seven questions related to teamwork; communication, cooperation, coordination, team climate, adaptability, situation awareness regarding perception and projection. The teamwork mean rating was 2.9/4, and national responders reported a higher rating than international responders (p = 0.004).

For each of the seven questions national responders reported higher satisfaction than international responders. With the exception of question eight (monitoring and assessing situation), there was a statistically significant difference of teamwork ratings between national and international responders for each question (p = < 0.05). “Team membership changes a lot, lots of different people cycling through with limited direction provided. It was difficult for the external team and home country team to have so much change and lack of consistency.”

The highest rating within teamwork was in working together to complete tasks in a timely manner. Males reported high satisfaction relating to communication and collaboration (p = < 0.05). Effective communication was one of the most discussed teamwork topics. “Our group was good, but communication and direction from those above us was not well coordinated. Roles and expectations often not clear,” and “Communication and collaboration is the key”.

The lowest scores within the teamwork category were regarding morale and anticipating actions. One responder stated “some team members were not committed and some lacked confidence and capabilities so needed to constantly be supervised” and another commented on the need for laughter “surviving and laughing about the austere conditions and very long hours.”

Timely completion of work was raised as an issue, with one responder stating “I feel it was more kind of damage control exercise, if we have acted more swiftly we could have done better.”

Task management

Task management was considered in two categories; prioritisation of tasks and following standards and guidelines. National responders once again reported significantly higher satisfaction than international responders (p = 0.003).

Respondents highlighted the cyclical nature of emergency response teams as a challenge for both teamwork as well as task management, “[I] saw things being repeated unnecessarily.”

Overall ‘non-technical’ rating

The final question provided a scale from 0 to 10 for participants to rate the overall performance of their epidemiology team [19]. Of those who answered (n = 138/166), the mean and median scores were both 7/10 (range 0–10). The TEAM tool states a score of 7 or less is considered ‘poor’; 70% (97/138) of participants in this survey gave an overall rating of 7 or less (Fig. 1). There was no statistical difference in scores between national and international responders for this question.

TEAM tool verification and reliability

The TEAM tool comprised three latent variables (inferred rather than directly observed variables); leadership, teamwork, and task management. Our exploratory factor analysis identified only two latent themes, with the original teamwork and task management being highly correlated (Table 4). The Cronbach alpha for the two identified factors indicated acceptable internal consistency for two factors (Table 4). Our confirmatory factor analysis found that the factor loading on most questions was under 0.5 (Fig. 2), therefore not reflecting the three latent variables identified in the original tool [19]. Although face validity appears to be supported by the two factor solution, the confirmatory factor analysis findings indicate that the questionnaire does not measure its intended concepts in our survey and study population.

Discussion

We described epidemiologists’ experiences of team dynamics and leadership, and tested the utility of the TEAM tool for use during public health emergency response. Unfortunately, the tool tested in this study did not satisfactorily perform in our emergency response setting, we were unable to verify the three themes of leadership, teamwork, and task management through either confirmatory or exploratory factor analysis. Although the face validity of the TEAM tool appears to suitably address the identified latent variables, the confirmatory factor analysis findings indicate that the questionnaire did not measure its intended concepts in our survey and study population. Despite being unable to validate the TEAM tool in this setting, we gained important insights into emergency response team performance from the perspective of epidemiologists.

Performance management

The effectiveness of emergency response teams is critical to mitigating the impact of an emergency response on an affected population. Performance management of individuals and teams is an important issue to improve and monitor the quality of emergency response. Performance management through such tools as after action reviews and outbreak response debriefs have been shown to improve team performance by 20–25% [27]. Implementation of these tools, however, are often conducted after the response.

Research has identified that emergency response setting has multiple challenges that directly affect teams and their performance. These challenges include the identification, availability, and selection of suitable individuals, high staff rotation and short contracts, minimal understanding of roles, and limited collective competence amongst teams [4, 12, 28]. Considering Tuckman’s team lifecycle within the context of these challenges, monitoring of human resources during emergency response is needed [6]. Teams need support to form and better collaborate as a team during a high stress, fast moving event. Performance management of individuals and the team as a whole may support this progress.

Given the unusual environment and known team dynamic challenges within emergency response settings, teams would benefit from the development and implementation of a real time (or close to it), customised team performance tool.

Leadership and team effectiveness

Managing emergency response settings requires leadership and collaboration [13]. The impact of team dynamics, team confidence, and team management during emergency response influence the team effectiveness, and in turn impact the effectiveness of response [12, 13]. The stress of a crisis, however, often makes teamwork and collaboration difficult to sustain [29, 30].

Tuckman’s team lifecycle is important to consider in regards to leadership also [6]. Emergency response leaders need skills in managing a fluctuating team through a high stress, fast moving event. Due to the identified team challenges, response leaders need to acknowledge that their team are unlikely to progress to, or maintain a high level of performance. For this reason, response leaders need strategies to better lead a team through the early team phases identified in Tuckman’s team phases.

Strong and clear leadership is critical for team functionality. However, our findings indicate leadership is often lacking in the emergency response setting for public health response. Our study identified consistent differences in the perception of leadership by gender. We also identified that national responders consistently rated their team performance and leadership as higher than the international responders in the survey, across all categories. Leadership and team interaction are often culturally and contextually bound [31]. Satisfaction in leadership is relative to expectations of leadership, this is an important finding to test in future studies. Different styles of leadership have been shown to have a positive impact on individuals as well as team satisfaction, this would be an important element to review in future studies also [32, 33].

An important aspect of teamwork identified in this study was enjoyment. Emergency response is often conducted under difficult conditions, with enormous time pressures, and high risk for the impacted community as well as the response team. The ability to laugh and keep morale high was reported by participants as needed and appreciated to keep team morale high.

Given the complexity of emergency response, any future team performance tool will need to look beyond leadership, teamwork, and task management. The dynamic nature of team composition adds a level of complexity which those three themes do not capture. Any future performance tool would need to take these issues into consideration. Our research identified that an effective team is collectively competent, with a mix of experience, skills, and perceptions. Clear roles and communication are essential, as is a sense of belonging and purpose [34, 35]. A team needs a mix of people with experience in emergency response, to enable mentorship, learning, and direction [36]. An emergency response team also require team resilience and ‘productive divergence’, with differences of opinion to help energise a team [7]. Critically, team effectiveness during emergencies relies on strong and clear leadership. Our findings on leadership corroborate previous research that indicates team effectiveness and innovation improve when leadership is agile to team needs and clear with team roles [4, 7, 12, 37]. Table 5 outlines our findings in this paper against Tuckman’s team lifecycle [6].

Limitations

This survey was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, however the findings are equally as relevant now. A study limitation was obtaining an accurate denominator for the target population as the number of responders and scale of emergencies change from year-to-year with workforce shifting according to need and organisational funding.

There were varying timeframes between emergency response and survey completion amongst survey participants. Participants may therefore have different levels of recall, and people with extremely negative or positive response experiences may remember differently. Participants may have had differing levels of expectation of their team and leadership, this was unable to be tested in this study.

There was a potential for selection bias as it was self-administered online. We attempted to lessen the impact of this bias by using multiple pathways to recruit participants and collaborated closely with emergency response partners. As the survey was available in French and English, this aimed to increase representation from a variety of people and contexts, however this may have missed valuable information from other language groups.

Conclusion

Our study provides further evidence that collective competence is needed and leadership skills are vital for teams to effectively respond to emergencies. We recommend further research to understand the gender differences identified in this study. We also recommend development of a team performance tool for simple continuous mid-response assessment, to ensure issues can be addressed proactively and for leaders to better understand and manage the team dynamics especially within international teams.

Availability of data and materials

All data relevant to this manuscript are included within the manuscript tables, figurers and/or reference links.

Abbreviations

- FETP:

-

Field Epidemiology Training Program

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TEAM:

-

Team Emergency Assessment Measure

- TEPHIConnect:

-

Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network alumni

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Carlson CJ, Albery GF, Merow C, Trisos CH, Zipfel CM, Eskew EA, et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature. 2022;28:1–1.

Griffith MM, Parry A, Housen T, Stewart T, Kirk M. COVID-19: A lesson for investing in applied epidemiology. Bull World Health Organ. 100(7):415-415A.

Boreham N. A Theory of Collective Competence: Challenging The Neo-Liberal Individualisation of Performance at Work. Br J Educ Stud. 2004;52(1):5–17.

Parry AE, Kirk MD, Durrheim DN, Olowokure B, Colquhoun S, Housen T. Emergency response and the need for collective competence in epidemiological teams. Bull World Health Organ. 2021;99(5):351–8.

Parry AE, Kirk MD, Durrheim DN, Olowokure B, Housen T. Study protocol: building an evidence base for epidemiology emergency response, a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(6):e037326.

Tuckman BW. Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63(6):384–99.

Lingard L, Sue-Chue-Lam C, Tait GR, Bates J, Shadd J, Schulz V. Pulling together and pulling apart: influences of convergence and divergence on distributed healthcare teams. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(5):1085–99.

Parry A, Kirk M, Durrheim D, Olowokure B, Colquhoun S, Housen T. Sha** applied epidemiology workforce training to strengthen emergency response: a global survey of applied epidemiologists, 2019–2020. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):58.

Olu O, Usman A, Kalambay K, Anyangwe S, Voyi K, Orach CG, et al. What should the African health workforce know about disasters? Proposed competencies for strengthening public health disaster risk management education in Africa. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):60.

Holding M, Ihekweazu C, Stuart JM, Oliver I. Learning from the Epidemiological Response to the 2014/15 Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2019;9(3):169–75.

Rexroth, U D M, Peron E, Winter, C, and der Heiden, M, Gilsdorf, A. Ebola response missions: To go or not to go? Cross-sectional study on the motivation of European public health experts. Eurosurveillance;December 2014. Available from: https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.12.21070.[Cited 13 Aug 2019].

Parry AE, Kirk MD, Colquhoun S, Durrheim DN, Housen T. Leadership, politics, and communication: challenges of the epidemiology workforce during emergency response. Hum Resour Health. 2022;20(1):33.

Boet S, Etherington C, Larrigan S, Yin L, Khan H, Sullivan K, et al. Measuring the teamwork performance of teams in crisis situations: a systematic review of assessment tools and their measurement properties. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(4):327–37.

Cooper S, Cant R, Connell C, Sims L, Porter JE, Symmons M, et al. Measuring teamwork performance: Validity testing of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) with clinical resuscitation teams. Resuscitation. 2016;1(101):97–101.

Cooper S, Cant R, Porter J, Sellick K, Somers G, Kinsman L, et al. Rating medical emergency teamwork performance: Development of the Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM). Resuscitation. 2010;81(4):446–52.

Maignan M, Koch FX, Chaix J, Phellouzat P, Binauld G, CollombMuret R, et al. Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM) for the assessment of non-technical skills during resuscitation: Validation of the French version. Resuscitation. 2016;1(101):115–20.

Cant RP, Porter JE, Cooper SJ, Roberts K, Wilson I, Gartside C. Improving the non-technical skills of hospital medical emergency teams: The Team Emergency Assessment Measure (TEAM™). Emerg Med Australas EMA. 2016;28(6):641–6.

McKay A, Walker ST, Brett SJ, Vincent C, Sevdalis N. Team performance in resuscitation teams: Comparison and critique of two recently developed scoring tools. Resuscitation. 2012;83(12):1478–83.

Cooper, Simon. Emergency Teamwork Assessment (The TEAM Tool). Available from: http://medicalemergencyteam.com/

Simon Cooper. TEAM – The TeamTM is a valid, reliable and feasible measure of teamwork in medical emergencies. Available from: http://medicalemergencyteam.com/. [Cited 10 Nov 2020].

Deborah K. Padget. SAGE Publications: Qualitative and Mixed Methods in Public Health; 2012.

Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed Methods Sampling: A Typology With Examples. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1(1):77–100.

Taber KS. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Develo** and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res Sci Educ. 2018;48(6):1273–96.

Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using Multivariate Statistics: Pearson New International Edition PDF EBook. Harlow, UNITED KINGDOM: Pearson Education, Limited; 2013. Available from: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/anu/detail.action?docID=5175291. [Cited 15 Sept 2021].

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ. 1997;314(7080):572.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;27(2):53–5.

Tannenbaum SI, Cerasoli CP. Do Team and Individual Debriefs Enhance Performance? A Meta-Analysis Hum Factors. 2013;55(1):231–45.

Greiner AL, Stehling-Ariza T, Bugli D, Hoffman A, Giese C, Moorhouse L, et al. Challenges in Public Health Rapid Response Team Management. Health Secur. 2020;18(S1):S8-13.

Tannenbaum SI, Traylor AM, Thomas EJ, Salas E. Managing teamwork in the face of pandemic: evidence-based tips. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(1):59–63.

Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the Health Care Workforce During the COVID-19 Global Epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1439–40.

Plaister-Ten J. Transpersonal Leadership Series: white paper four. Leading Across Cultures, develo** leraders for gloabl organisations. UK: LeaderShape Global. https://www.leadershapeglobal.com/whitepapers.

Saleem H. The Impact of Leadership Styles on Job Satisfaction and Mediating Role of Perceived Organizational Politics. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2015;172:563–9.

Joanne Lyubovnikova, Alison Legood, Nicola Turner, and Argyro Mamakouka. How Authentic Leadership Influences Team Performance: The MediatingRole of Team Reflexivity. Aston University; Available from: https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/25675/1/Authentic_leadership_influences_team_performance_mediating_role_of_team_reflexivity.pdf

McLeod SA. Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. 2022. https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html.

Ko Y, Lee H, Hyun SS. Airline Cabin Crew Team System’s Positive Evaluation Factors and Their Impact on Personal Health and Team Potency. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):10480.

Parry A, Colquhoun S, Brownbill A, Lynch B, Housen T. Navigating Uncertainty: Evaluation of a COVID-19 Surge Workforce Support Program, Australia 2020–2021. Glob Biosecurity. 2021 Nov 24;3(1). https://jglobalbiosecurity.com/articles/10.31646/gbio.124. https://doi.org/10.31646/gbio.124.

Peralta CF, Lopes PN, Gilson LL, Lourenço PR, Pais L. Innovation processes and team effectiveness: The role of goal clarity and commitment, and team affective tone. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2015;88(1):80–107.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the participants of the survey for sharing your knowledge and experience. Thank you also to TEPHIconnect, FETP programme directors, and TEPHINET networks, for distributing the survey to members and for support with survey recruitment.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. AP received Commonwealth and ANU science merit scholarships, along with funding from the Australian National Health Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response (APP1107393). MDK was supported by an NHMRC fellowship (APP1145997) and received funding from the NHMRC for Integrated Systems for Epidemic Response. The funders did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP wrote the manuscript, conducted analysis, and led the study; TH, DD, MK supported study design development, TH, DD, MK, SC, AR supported data analysis interpretation and revised the manuscript critically. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All activities were approved by the Science and Medical Delegated Ethics Review Committee at the Australian National University (protocol number 2019–068). All participants provided consent prior to accessing online survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Parry, A.E., Richardson, A., Kirk, M.D. et al. Team effectiveness: epidemiologists’ perception of collective performance during emergency response. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 149 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09126-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09126-y