Abstract

Background

The objective of this study is to identify and evaluate the risk factors associated with the development of postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) in elderly patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy under general anesthesia.

Methods

The retrospective study consecutively included elderly patients (≥ 70 years old) who underwent thoracoscopic lobectomy at Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University from January 1, 2018 to August 31, 2023. The demographic characteristics, the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative parameters were collected and analyzed using multivariate logistic regression to identify the prediction of risk factors for PPCs.

Results

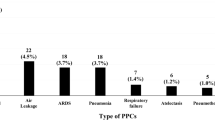

322 patients were included for analysis, and 115 patients (35.7%) developed PPCs. Multifactorial regression analysis showed that ASA ≥ III (P = 0.006, 95% CI: 1.230 ∼ 3.532), duration of one-lung ventilation (P = 0.033, 95% CI: 1.069 ∼ 4.867), smoking (P = 0.027, 95% CI: 1.072 ∼ 3.194) and COPD (P = 0.015, 95% CI: 1.332 ∼ 13.716) are independent risk factors for PPCs after thoracoscopic lobectomy in elderly patients.

Conclusion

Risk factors for PPCs are ASA ≥ III, duration of one-lung ventilation, smoking and COPD in elderly patients over 70 years old undergoing thoracoscopic lobectomy. It is necessary to pay special attention to these patients to help optimize the allocation of resources and enhance preventive efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are highly prevalent complications during the perioperative period, affecting many patients [1, 2]. These complications significantly influence patients’ outcome, prolong hospital stay, and increase perioperative mortality. PPCs, including respiratory infection, pleural effusion, respiratory failure, atelectasis, bronchospasm, pneumothorax and aspiration pneumonitis, can be caused by various factors such as patient health status, surgical trauma and anesthetic effects [3, 4].

PPCs can occur following any type of surgery, but certain surgeries carry higher risk. The incidence of PPCs is particularly high in major abdominal surgery, thoracic surgery, cardiac surgery and spinal surgery, which seriously threatens the perioperative safety of these patients [5, 6]. Previous studies have focused on these high-risk surgeries and identified several independent risk factors for PPCs. However, there still lack of study on PPCs following thoracic surgery, especially on the risk factors for PPCs after pulmonary lobectomy. It is reported that the incidence of PPCs in thoracic surgery can be as high as 20 ∼ 50%, posing a significant threat to patients undergoing high-risk thoracic surgeries [7, 8]. Identifying and mitigating these risk factors is essential for improving outcomes in thoracic patients.

Pulmonary lobectomy is a common surgical treatment for lung diseases such as lung cancer and emphysema. In thoracic surgery, lobectomy involves a large resection range and significant trauma, which can have substantial impacts on pulmonary function [9]. In recent years, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has been widely applied due to its advantages such as less tissue trauma and enhanced postoperative recovery [10, 11]. However, PPCs are still common following VATS lobectomy. These complications range from mild atelectasis and pneumonia to severe respiratory failure and sepsis, posing a considerable threat to the perioperative safety of patients [5]. Previous studies have shown that advanced age is one of the independent risk factors for PPCs [12]. This may be related to the age-related decline in pulmonary function and immune responsiveness in elderly patients [13]. Age-related physiological changes can lead to a decrease in pulmonary function, weakened immune response, reduced tolerance to surgery, and increased risk of PPCs [21]. This may be due to differences in the study population and surgical type in different studies.

In recent years, obesity has become one of the major global epidemics, affecting the health of individuals worldwide. Previous studies have shown that obesity is closely associated with PPCs [22, 23]. Obese patients often face greater surgical challenges and have poorer postoperative recovery of cardiopulmonary function [24]. According to the WHO standards for Asians, BMI ≥ 28 is considered obese. However, there was no significant statistical difference in the incidence of PPCs between the BMI ≥ 28 group and the BMI < 28 group in the current study. The possible reasons may be that the sample size is still relatively small, or there are differences in the surgical types and the studied population. Clinically, obese patients may have the increased risk of PPCs due to impaired oxygen exchange function, elevated risk of hypoxemia and delayed recovery of cardiopulmonary function. Therefore, preoperative assessment and preparation for obese patients are very importance, with a specific focus on maintaining pulmonary function during the perioperative period.

In previous studies, smoking has been identified as a significant risk factor for the development of PPCs [25, 26]. This study also confirms this point. The harmful substances present in tobacco, including tar and nicotine, have the potential to cause damage to the airway epithelium, leading to a reduction in the airway’s ability to clear debris effectively. This damage results in an increase in mucus production and a decrease in lung compliance, ultimately compromising pulmonary function. Furthermore, smokers exhibit shorter and irregularly shaped cilia on the bronchial epithelium, which impairs mucus clearance and predisposes them to postoperative pulmonary infections [27]. Previous study has shown that patients who continue to smoke within two weeks prior to surgery are at a significantly increased risk of develo** postoperative pulmonary infections compared to those who quit smoking at least two weeks prior to surgery [26]. It suggests that smoking cessation prior to surgery may be a feasible strategy to reduce the risk of PPCs and improve outcomes following thoracic surgery. Unfortunately, the detail information relating whether smoking patients had quitted smoking before surgery could not be obtained in our retrospective electronic records. Prospective studies remain to be conducted to further determine the correlation of smoking cessation and PPCs for smoking patients.

Previous studies have investigated the duration of operation and found that longer operation time is closely related to the increase of pulmonary complications [3, 28]. In addition to studying the duration of operation, this study also includes the duration of OLV intraoperatively. The results showed that the duration of operation and the duration of OLV were significantly associated with PPCs in univariate analysis. However, multivariate analysis showed that only the duration of OLV was the independent risk factor for PPCs, while the duration of operation was not. Since the main surgical steps of pulmonary lobectomy are performed under OLV, it seems to indicate that the longer duration of OLV is one of the main causes of intraoperative potential lung injury and PPCs. OLV is a commonly used lung isolation technique in thoracic surgery. OLV often leads to the significant increase in airway pressure and excessive ventilation pressure. Prolonged higher-pressure ventilation time may cause lung contusion, edema, exacerbation of inflammatory reactions and even cause pulmonary hemorrhage. Besides, previous studies have shown that continuous OLV during surgery produces a large amount of oxygen free radicals and the longer the operation time, the longer the OLV time, and the more oxygen free radicals produced [29]. In addition, the potential damage of OLV includes hypoxemia, atelectasis and pulmonary edema [30]. The quality and duration of intraoperative OLV are mainly related to the anesthetic and surgical techniques. Therefore, it is important to develop a rigorous and meticulous surgical plan before surgery and strengthen team cooperation to minimize the duration of OLV. Pulmonary protection strategies during OLV are also topics that require further exploration in the future.

Previous studies have shown that the effect of postoperative analgesia is correlated with the occurrence of PPCs [31]. Moderate to severe postoperative pain may lead to respiratory restrictions for patients. The pain may make patients unwilling to take deep breaths or cough, which may result in the retention of pulmonary secretions, increasing the risk of atelectasis and pulmonary infection. However, there was no statistically significant difference in postoperative analgesia and VAS scores between the PPCs group and the None-PPCs group in the univariate analysis of this study. One of the possible reasons is that the surgeons have administered additional analgesic drugs to relieve their pain for most patients with moderate to severe pain. Patients who experienced moderate to severe pain on the first day after surgery mostly received good pain management subsequently.

In this study, we collected preoperative pulmonary comorbidities including chronic bronchitis, COPD and asthma. The results of regression analysis showed that COPD is one of the independent risk factors for PPCs. This is consistent with previous studies [32, 33]. Elderly patients over 70 years old who undergo thoracic surgery often have multiple comorbidities. The results demonstrate that pulmonary comorbidities have the closest relationship with PPCs compared to other system comorbidities. This is primarily because patients with pulmonary comorbidities may have poorer baseline pulmonary function. Additionally, surgical trauma, anesthesia and mechanical ventilation can all exacerbate ventilatory and gas exchange dysfunction, as well as affect airway mucosal secretions and expectoration [13]. COPD is a prevalent respiratory disorder that is typically marked by persistent airflow limitation, with main symptoms including chronic cough, sputum production and dyspnea. Due to the impaired pulmonary function in patients with COPD, they face the higher risk of PPCs following surgical procedures [34]. Therefore, there is a close relationship between COPD and PPCs. For patients with COPD, preoperative evaluation and postoperative management are crucial.

There are certain limitations of this study. Firstly, this study is a retrospective study conducted in a single center with a relatively small sample size (322 cases), some uncertainty may exist. Secondly, the time and severity of PPCs were not further stratified. The observation indicators of this study were PPCs within 7 days, while short-term pulmonary complications after discharge were not included. This may affect the statistical analysis of the incidence and risk factors of PPCs. The time and severity of pulmonary complications are important for patient prognosis. We can further collect the detailed time and severity of PPCs for deeper analysis in the future. Thirdly, in terms of case data collection, due to the hospital’s electronic case system constraints, some important clinical examination indicators were not fully collected, so they were not discussed in this study. Further conclusions require multi-center, prospective clinical studies for verification.

Conclusions

In summary, PPCs in elderly patients (≥ 70 years old) who undergo VATS lobectomy are affected by multiple factors. The present study has identified ASA ≥ III, duration of OLV, smoking and COPD as potential independent risk factors for PPCs. The analysis of risk factors for PPCs in high-risk individuals provides valuable and reliable indicators for assessing the risk of these complications. This information can assist in identifying high-risk patients in clinical practice and taking targeted preparations and interventions before surgery to proactively prevent PPCs. It is particularly important to perform rigorous and cautious preoperative assessments, personalized perioperative management and multidisciplinary comprehensive treatment for these high-risk patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PPCs:

-

Postoperative pulmonary complications

- VATS:

-

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

- EPCO:

-

European Perioperative Clinical Outcome

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- LOS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- OLV:

-

One-lung ventilation

References

Haines KL, Agarwal S. Postoperative pulmonary Complications-A multifactorial outcome. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(2):166–7.

Kaufmann K, Heinrich S. Minimizing postoperative pulmonary complications in thoracic surgery patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34(1):13–9.

Chandler D, Mosieri C, Kallurkar A, Pham AD, Okada LK, Kaye RJ, Cornett EM, Fox CJ, Urman RD, Kaye AD. Perioperative strategies for the reduction of postoperative pulmonary complications. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2020;34(2):153–66.

Jammer I, Wickboldt N, Sander M, Smith A, Schultz MJ, Pelosi P, Leva B, Rhodes A, Hoeft A, Walder B, et al. Standards for definitions and use of outcome measures for clinical effectiveness research in perioperative medicine: European Perioperative Clinical Outcome (EPCO) definitions: a statement from the ESA-ESICM joint taskforce on perioperative outcome measures. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2015;32(2):88–105.

Miskovic A, Lumb AB. Postoperative pulmonary complications. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):317–34.

Sakatoku Y, Fukaya M, Miyata K, Itatsu K, Nagino M. Clinical value of a prophylactic minitracheostomy after esophagectomy: analysis in patients at high risk for postoperative pulmonary complications. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):120.

Thorpe A, Rodrigues J, Kavanagh J, Batchelor T, Lyen S. Postoperative complications of pulmonary resection. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(11):876. e871-876 e815.

Lusquinhos J, Tavares M, Abelha F. Postoperative pulmonary complications and perioperative strategies: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e38786.

Veronesi G, Novellis P, Perroni G. Overview of the outcomes of robotic segmentectomy and lobectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(10):6155–62.

Martin JL, Mack SJ, Rshaidat H, Collins ML, Whitehorn GL, Grenda TR, Evans Iii NR, Okusanya OT. Wedge Resection Outcomes: A Comparison of Video-Assisted and Robotic-Assisted Wedge Resections. The Annals of thoracic surgery 2024.

Huang L, Kehlet H, Petersen RH. Readmission after enhanced recovery video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery wedge resection. Surgical endoscopy 2024.

Nijbroek SG, Schultz MJ, Hemmes SNT. Prediction of postoperative pulmonary complications. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019;32(3):443–51.

Soma T, Nagata M. Immunosenescence, Inflammaging, and Lung Senescence in Asthma in the Elderly. Biomolecules 2022, 12(10).

**a S, Zhou C, Kalionis B, Shuang X, Ge H, Gao W. Combined Antioxidant, anti-inflammaging and mesenchymal stem cell treatment: a possible therapeutic direction in Elderly patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Aging Dis. 2020;11(1):129–40.

Bevilacqua Filho CT, Schmidt AP, Felix EA, Bianchi F, Guerra FM, Andrade CF. Risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications and prolonged hospital stay in pulmonary resection patients: a retrospective study. Braz J Anesthesiol. 2021;71(4):333–8.

Ma L, Yu X, Zhang J, Shen J, Zhao Y, Li S, Huang Y. Risk factors of postoperative pulmonary complications after primary posterior fusion and hemivertebra resection in congenital scoliosis patients younger than 10 years old: a retrospective study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):89.

Bade BC, Blasberg JD, Mase VJ Jr., Kumbasar U, Li AX, Park HS, Decker RH, Madoff DC, Brandt WS, Woodard GA, et al. A guide for managing patients with stage I NSCLC: deciding between lobectomy, segmentectomy, wedge, SBRT and ablation-part 3: systematic review of evidence regarding surgery in compromised patients or specific tumors. J Thorac Dis. 2022;14(6):2387–411.

Odor PM, Bampoe S, Gilhooly D, Creagh-Brown B, Moonesinghe SR. Perioperative interventions for prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;368:m540.

Schwartz J, Parsey D, Mundangepfupfu T, Tsang S, Pranaat R, Wilson J, Papadakos P. Pre-operative patient optimization to prevent postoperative pulmonary complications-insights and roles for the respiratory therapist: a narrative review. Can J Respiratory Therapy: CJRT = Revue canadienne de la Ther respiratoire : RCTR. 2020;56:79–85.

Canet J, Gallart L. Predicting postoperative pulmonary complications in the general population. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2013;26(2):107–15.

Garutti I, Errando CL, Mazzinari G, Bellon JM, Diaz-Cambronero O, Ferrando C. I pn: spontaneous recovery of neuromuscular blockade is an independent risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery: a secondary analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2020;37(3):203–11.

Covarrubias J, Grigorian A, Schubl S, Gambhir S, Dolich M, Lekawa M, Nguyen N, Nahmias J. Obesity associated with increased postoperative pulmonary complications and mortality after trauma laparotomy. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2020.

Mafort TT, Rufino R, Costa CH, Lopes AJ. Obesity: systemic and pulmonary complications, biochemical abnormalities, and impairment of lung function. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:28.

Huang L, Wang ST, Kuo HP, Delclaux C, Jensen ME, Wood LG, Costa D, Nowakowski D, Wronka I, Oliveira PD, et al. Effects of obesity on pulmonary function considering the transition from obstructive to restrictive pattern from childhood to young adulthood. Obes Rev. 2021;22(12):e13327.

Collaborative ST, Collaborative T. Evaluation of prognostic risk models for postoperative pulmonary complications in adult patients undergoing major abdominal surgery: a systematic review and international external validation cohort study. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(7):e520–31.

Varga JT. Smoking and pulmonary complications: respiratory prehabilitation. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(Suppl 5):S639–44.

Kotlyarov S. The role of smoking in the mechanisms of Development of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(10).

Scholes RL, Browning L, Sztendur EM, Denehy L. Duration of anaesthesia, type of surgery, respiratory co-morbidity, predicted VO2max and smoking predict postoperative pulmonary complications after upper abdominal surgery: an observational study. Aust J Physiother. 2009;55(3):191–8.

Piccioni F, Langiano N, Bignami E, Guarnieri M, Proto P, D’Andrea R, Mazzoli CA, Riccardi I, Bacuzzi A, Guzzetti L, et al. One-lung ventilation and postoperative pulmonary complications after major lung resection surgery. A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2023;37(12):2561–71.

Shum S, Huang A, Slinger P. Hypoxaemia during one lung ventilation. BJA Educ. 2023;23(9):328–36.

Yan G, Chen J, Yang G, Duan G, Du Z, Yu Z, Peng J, Liao W, Li H. Effects of patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone or sufentanil on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing thoracic surgery: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):192.

Marlow LL, Lee AHY, Hedley E, Grocott MP, Steiner MC, Young JD, Rahman NM, Snowden CP, Pattinson KTS. Findings of a feasibility study of pre-operative pulmonary rehabilitation to reduce post-operative pulmonary complications in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease scheduled for major abdominal surgery. F1000Res. 2020;9:172.

Bayable SD, Melesse DY, Lema GF, Ahmed SA. Perioperative management of patients with asthma during elective surgery: a systematic review. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;70:102874.

Wang L, Yu M, Ma Y, Tian R, Wang X. Effect of Pulmonary Rehabilitation on Postoperative Clinical Status in Patients with Lung Cancer and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022, 2022:4133237.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr. Wei Gao for his valuable assistance in the process of data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by the Post-subsidy funds for National Clinical Research Center, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Tianlong Wang: 303-01-001-0272-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: GF and TW. Data acquisition and validation: GF, YJ, and GZ. Statistical analysis and data management: GF and TW. Manuscript editing: GF and YJ. Manuscript reviewing: FM and TW. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University (2022 No.028). Since this is a retrospective study, informed consent from patients is not required.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, G., Jia, Y., Zhao, G. et al. Risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications in elderly patients undergoing video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy under general anesthesia: a retrospective study. BMC Surg 24, 153 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02444-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02444-w