Abstract

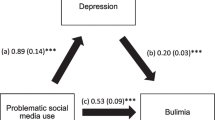

Bulimia, which means a person has episodes of eating a very large amount of food (bingeing) during which the person feels a loss of control over their eating, is the most primitive reason for being overweight and obese. The extended literature has indicated that childhood emotional abuse has a close relationship with adverse mood states, bulimia, and obesity. To comprehensively understand the potential links among these factors, we evaluated a multiple mediation model in which anxiety/depression and bulimia were mediators between childhood emotional abuse and body mass index (BMI). A set of self-report questionnaires, including the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), Beck Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI), was sent out. Clinical data from 37 obese patients (age: 29.65 ± 5.35, body mass index (BMI): 37.59 ± 6.34) and 37 demographically well-matched healthy people with normal body weight (age: 31.35 ± 10.84, BMI: 22.16 ± 3.69) were included in the investigation. We first performed an independent t-test to compare all scales or subscale scores between the two groups. Then, we conducted Pearson correlation analysis to test every two variables’ pairwise correlation. Finally, multiple mediation analysis was performed with BMI as the outcome variable, and childhood emotional abuse as the predictive variable. Pairs of anxiety, bulimia, and depression, bulimia were selected as the mediating variables in different multiple mediation models separately. The results show that the obese group reported higher childhood emotional abuse (t = 2.157, p = 0.034), worse mood state (anxiety: t = 5.466, p < 0.001; depression: t = 2.220, p = 0.030), and higher bulimia (t = 3.400, p = 0.001) than the healthy control group. Positive correlations were found in every pairwise combination of BMI, childhood emotional abuse, anxiety, and bulimia. Multiple mediation analyses indicate that childhood emotional abuse is positively linked to BMI (β = 1.312, 95% CI = 0.482–2.141). The model using anxiety and bulimia as the multiple mediating variables is attested to play roles in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and obesity (indirect effect = 0.739, 95% CI = 0.261–1.608, 56.33% of the total effect). These findings confirm that childhood emotional abuse contributes to adulthood obesity through the multiple mediating effects of anxiety and bulimia. The present study adds another potential model to facilitate our understanding of the eating psychopathology of obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When we consider reasons for overweight and obesity, the early environment is particularly important to address [1]. Eating patterns are often potentially established in childhood and contribute to epigenetic changes and subsequent weight difficulty development [2, 3]. Research has reliably demonstrated associations between childhood maltreatment and body mass index (BMI) [4,5,6]. Stressful and traumatic childhood abuse experiences highly increase the risk of adulthood overweight [7,8,9,10]. The association between childhood traumatic experiences and adulthood obesity has been confirmed [11]. While childhood sexual and physical abuse were also hypothesized to be risk factors in multifactorial models of obesity, the role of emotional abuse gradually gained more attention. Childhood emotional abuse means a sustained, repetitive, inappropriate emotional response to the child’s experience of emotion. Among all kinds of childhood trauma, emotional abuse is highly prevalent and easily occurs since inappropriate emotional responses are instantaneous, less effort is spent by abusers, and the consequence of emotional hurt is insidious and difficult to detect [12]. Childhood emotional abuse is central to understanding the latent effects of child maltreatment, and its potential importance in the etiology of obesity needs further investigation [13].

One possible mediating factor in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and adult obesity is anxiety. Childhood emotional abuse has a long-term effect on psychiatric performance [14,15,16,17]. Specifically, childhood emotional abuse is particularly relevant to the development of anxiety and depression [5, 18,19,20]. Furthermore, the study showed that obese people are worse in indicators of happiness, perceived mental health, life satisfaction, positive affect, negative affect, optimism, feeling loved and cared for, and depression [21]. Obesity may have long-term implications for mental distress at a clinical level over the adult years [22]. Some studies have shown that obesity is associated with an increase in lifetime anxiety disorders [23, 24]. A meta-analysis review of cross-sectional studies confirmed the association between obesity and anxiety and concluded that obesity was also associated with past-year and lifetime anxiety prevalence [25].

Another possible mediating factor between childhood emotional abuse and obesity is bulimia, which is an eating disorder behavior indicated by a tendency to eat a large amount of food in a short time [26]. Bulimia has a similar meaning to bingeing describing a tendency of excessive or uncontrolled indulgence, especially in food or drink. It is also considered a key symptom of the eating disorder. The literature consistently suggests a close association between bulimia and obesity [2, 27,28,29]. Bulimia is the most shared direct risk factor for obesity. Distressing psychological states such as anxiety and depression are also likely to increase indulgent food intake, frequent emotional overeating, and bulimia, which are unhealthy eating behaviors that contribute to high rates of obesity [30]. For example, a study has shown that greater attachment anxiety is predictive of a heavier body mass index [31]. A positive correlation has been examined between social anxiety disorder and binge eating frequency [32, 33]. In weight-loss surgery candidates, higher attachment anxiety is associated with a greater incidence of bulimia [34]. In addition, a systematic literature review indicated that some studies demonstrate an association between depression and binge eating disorder, but carefully designed studies are required [35]. While many studies have suggested a negative emotional effect on bulimia, the role of anxiety may be more important for future research [36]. Therefore, we hypothesize that anxiety is a more important mediating factor in the present study.

The prevailing view is that the relationships between anxiety, overeating, and body mass index can be explained in terms of emotion regulation [37]. The emotion regulation system connects to eating behavior by balancing different mental dimensions. Due to early adverse emotional experiences, individuals tend to be hyperactivated to potentially upsetting/stressful negative social cues. They are relatively poor at managing their emotions and thus more likely to be anxious [38, 39]. Therefore, to ‘soothe’ themselves, some anxious individuals rely on external sources of affect regulation such as food, while others may choose to rely on smoking, substance misuse, etc. [40]. Studies have proven that anxiety is specifically related to emotional eating among weight-loss surgery candidates [41]. Obesity seems to involve higher emotional dysregulation than normal weight conditions [42]. Emotion regulation is essential in the relationship between anxiety and bulimia, as it could represent a risk factor for the worsening of problems related to overeating and excessive body weight [34]. Thus, the importance of the emotion regulation process has been considered in the success of weight-loss treatment and could provide significant clinical information and therefore be part of the obesity diagnostic criteria and therapeutic program [43].

The etiology and maintenance of obesity have been substantially advanced. Based on the preproved potential connections between childhood trauma, adverse mood state, and bulimia, we hypothesize that there are explicit multiple mediation models linking all the possible variables of childhood emotional abuse, anxiety/depression, and bulimia and obesity (body mass index). Here, we sampled some weight-loss surgery candidates at hospitals and well-matched healthy controls to establish multiple mediation models to (1) add an approval of the association between childhood emotional abuse and obesity; (2) reveal the potential pathway between childhood emotional abuse and obesity, in which anxiety/depression could serve as intermediate factors; and (3) compare the model fit to test whether anxiety/depression play an equal main mediating effect in this relationship. The multiple mediation models will help clinicians continue to disentangle interactions of these factors to further facilitate our understanding of eating psychopathology.

Method

Participants

From September 2020 to January 2021, obese patients who were going to have weight-loss surgery at the Department of Bariatric & Metabolic Surgery, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, were informed about the present study. Inclusion criteria for the obesity are (1) meet the indication of bariatric surgery: BMI ≥ 32.5 or BMI between 32.5 to 27.5 with comorbidity of metabolic syndromes; (2) aged above 18 years old; (3) able to read and understand the description of each item of the questionnaire; and (4) voluntarily participated in the survey and signed the informed consent form were invited to participate in the present study to answer a set of clinical scales. Department of Bariatric & Metabolic Surgery, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital handed out healthy control recruitment advertisements in the nearby community. Citizens who were interested in participating in the research would contact the experimenters directly. Inclusion criteria for the healthy controls are (1) with normal figures and do not meet the indication of bariatric surgery; (2) without any eating disorders; (3) demographically matched with obese patients’ characteristics (with similar means of age, education years and similar gender ratio); (4) voluntarily participated in the survey and signed the informed consent. Both participants in obesity and healthy control were first interviewed by a professional psychiatrist. Participants examined with psychiatric disorders would be excluded from the research. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, NO 2020–219-(1). All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Eventually, we analyzed the clinical data from 37 obese patients and 37 healthy people.

Clinical measurement

Basic demographic information (age, years of education, height, weight) and a series of clinical scales (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, CTQ; Beck Anxiety Inventory, BAI; Beck Depression Inventory, BDI; and Eating Disorders Inventory, EDI) were collected. Body mass index (BMI, equal to weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared) was calculated to describe the severity of obesity. All demographic information and clinical scales were presented to participants in the form of an online questionnaire designed by a professional psychologist. Participants answered all online questionnaires using their cell phones in the examination room with the supervision of experimenters. Demographic information on height and weight was self-reported by participants, experimenters would invite them to use the height and weight gauge in the examination room to measure these indexes when they are not sure.

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) [44] is designed for adolescents and adults to obtain a brief, reliable, and valid assessment of traumatic experiences in childhood [45, 46]. It assesses the incidents of abuse and neglect in childhood, including physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect [47]. The total Cronbach’s α of the Chinese version of the CTQ is 0.73 [44]. The CTQ has 28 items, including a minimization–denial subscale of 3 items, and each item adopts a 5-point Likert score from 1 “never” to 5 “always” according to the frequency of the experiences that occurred [46]. Scores for each of the categories include 5 items, ranging from 5 to 25. A higher CTQ score indicates more severe childhood trauma. The total CTQ Cronbach’s α of the present sample is 0.623, and the Cronbach’s α values of the physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect subscales are 0.648, 0.793, 0.641, 0.746, and 0.462, respectively.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory [48, 49] assesses the severity of generalized anxiety symptoms [50]. It has good reliability, validity, internal consistency, and convergence [51, 52]. The total Cronbach’s α of the Chinese version of the BAI is 0.95 [49]. The BAI has 21 items, with each response based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 “not at all” to 3 “severely”. A higher score indicates greater anxiety severity. The total BAI Cronbach’s α of the present sample is 0.920.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [53] version 2 is a widely used clinical instrument to evaluate depression severity in normal populations [54,55,56]. It has good reliability and validity [55]. The total Cronbach’s α of the Chinese version of the BDI is 0.94 [53]. The BDI has 21 items, and each item consists of four self-evaluative statements scored from 0 to 3, with an increasing score indicating greater depression severity. The total BDI Cronbach’s α of the present sample is 0.901.

The Eating Disorder Inventory version 2 (EDI-2) measures eating disorder symptoms and the cognitive and behavioral characteristics of anorexia nervosa and bulimia [65,66,67].

Anxiety is thought to be an important mediator of emotional abuse in childhood and obesity in adulthood. Childhood emotional abuse, involving a repeated pattern of caregiver behavior or a serious incident, transmits negative information to the child that he or she is worthless, flawed, unloved, unwanted, endangered, or only of value in meeting another’s needs [68]. Spurning, intimidating and terrorizing, confining and isolating, exploiting and corrupting, denigrating emotional needs, and neglecting health needs manifest negative impacts on a child’s emotions and daily functionality and seriously undermine a child’s future adaptation [69,70,71]. Mechanisms linking emotional abuse with anxiety include maladaptive self-experience, such as with resilience and self-esteem. Psychological maltreatment reduces children’s psychological resilience, which is a positive resource adolescents can utilize to manage stressful challenges [72,73,74]. Emotional abuse causes low self-esteem, including negative evaluations of oneself [75, 76]. Undeveloped self-experience highly increases susceptibility to develo** anxiety and depression by causing a series of difficulties identifying emotions and emotional awareness and is more likely to induce anxiety in adulthood [77]. These findings may explain the evidence of a higher prevalence of lifetime diagnosed anxiety in obesity [78].

Bulimia symptoms are considered emotionally induced psychosomatic symptoms, and the tendency to bulimia in obese people is closely related to obesity. To further prove the connection sequence of anxiety and bulimia, we built and examined a model in which bulimia was the first multiple mediating variable and anxiety was the second multiple mediating variable (SFig. 1). The model fitting result was less satisfactory than the original model (anxiety was the first multiple mediator variable; see Supplementary material: the regression coefficient of emotional abuse → bulimia → anxiety/depression → BMI was not significant, STables 1 and 2). According to previous studies, anxiety disorders commonly have an onset in childhood and frequently exist before eating disorders [79, 80]. The model fitting and clinical evidence indicated that childhood emotional abuse might primarily lead to anxious traits. The recurring anxious emotional state triggers more bulimic behavior and further leads to obesity.

Depression is thought to be a mediating factor outside of anxiety between childhood emotional abuse and adult obesity. Our study described one indirect pathway of childhood emotional abuse contributing to obesity and demonstrated that anxiety plays an important mediating role in this relationship. This result provides a new perspective for treating obese patients with adverse early life events. Beyond bariatric surgery, psychological intervention is also helpful in reducing the influence of predisposing pathogenic factors. In future treatment, it would be beneficial to offer obese patients psychological therapy to reduce their anxiety and bulimic behavior. Anxiety and obesity are the two most common related health problems [81]. It is highly possible that anxiety disorders would lead to weight gain. For stressed individuals, the dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis contributes to subsequent getting weight [82, 83]. Symptoms of anxiety stimulate a craving for high-sugar and high-fat foods [84,85,86]. Anxiety-related chronic conditions might also have an influence on functional health, which may cause physical inactivity leading to excess weight. Previous studies also reported that anxiety is strongly associated with binge eating and emotional eating [33]. Obese patients eat more when they feel anxious, and the aroused effect is significantly reduced after gluttonous eating [87]. Therefore, anxiety is a critical factor in the childhood emotional abuse–obesity relationship, since the high likelihood of an anxious emotional state triggers bulimic behavior. In contrast, the connection between depression and bulimia is ambiguous. A depressive state does not always increase eating. In a sample of depressed patients, only 14% indicated an increase in appetite, while in 66%, appetite decreased, and in 20%, it showed no change [88]. Bradley M. Appelhans et al. reported that more severe depression is associated with more inferior diet quality [89]. For these reasons, we believe that anxiety plays a vital role in leading these obese patients to perform more bulimic behavior, which could release their anxious impulses but cause excessive fat accumulation.

Many studies have suggested that unhealthy eating habits, including overeating and bulimia, could be the result of a failure to attempt to regulate negative emotions [90,91,92]. Lack of emotion regulation could lead to a breakdown in the autoregulation of other personal areas, including those linked to the control of eating behavior [93, 94]. Emotion regulation is the ability to regulate one’s own positive or negative emotions to diminish, attenuate, maintain, or amplify their content [95]. For obese patients, when their emotions are dysregulated, maladaptive behaviors can be adopted to encourage them to overeat in response to anxiety [94, 96]. The emotionally driven eating model explains inappropriate eating behaviors by suggesting dysfunctional emotional and cognitive processing as causes of overeating [97]. The deficit in the regulation of eating behavior can be attributed to a failure in emotional regulation that can lead to overeating behavior to compensate for an inability to employ proper cognitive strategies to avoid a negative emotional state [92, 98]. Therefore, the ability to regulate anxiety or dysphoric mood is associated with binge eating and emotional eating in overweight individuals and has been considered a critical target to reduce excess body weight [33, 99, 100]. The clinical implications of the proposed multiple mediation models in this research strengthen the obesity treatment idea that improving obese patients’ emotion regulation ability is an effective target to rectify unhealthy bulimia behavior. Some pilot randomized controlled trial studies have achieved some therapeutic effects. For example, Berking and Whitley developed emotion regulation training (EuREKA), which is an innovative intervention program for children and adolescents that aims to examine the effectiveness of emotion regulation training when combined with a multidisciplinary obesity treatment in inpatient-treated 10- to 14-year-old youngsters [101, 102]. Obese youngsters of the EuREKA program exhibited less emotional eating behavior and improved weight loss and weight-loss maintenance, causally proving that emotion regulation intervention can be applied in clinical practice [103].

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the obese participants recruited in the sample are patients seeking bariatric surgery in the hospital, which only presents a subpopulation of the obese. Compared to the obese, candidates for bariatric surgery display advantageous personality features and lower rates of psychopathology [104]. Second, its sample size is relatively small. Future studies need to collect a larger sample to make a firmer conclusion. Third, the present study is a cross-sectional investigation. All participants estimated their childhood experiences based on their retrospective memory. Longitudinal designs and interventional experiments should be adopted in future studies to reveal sequential causality. Finally, the data collection was based on the self-report questionnaire, which inevitably led to reported biases even though we strictly controlled the response quality. More objective indicators of neuroimaging are necessary. Childhood maltreatment reduces left-side hippocampal volumes [105,106,107] and the functional integrity of white matter tracts [108, 109]. Increased insula activation is involved in the neurological processing of food-related stimuli [110, 111]. Diminished frontostriatal activity contributes broadly to emotion, motivation, and movement processes and, importantly, is thought to underlie self-regulatory control [112]. More functional connections between related brain areas need to be confirmed to further substantiate the multiple mediation models of the present study. More evidence from random clinical trial research about emotional regulation training in obesity treatment will also make the current conclusion more stable.

In conclusion, obese patients experienced more childhood emotional abuse and were more anxious, depressive, and bulimic than healthy people. Childhood emotional abuse may contribute to adulthood obesity, potentially mediated by anxiety and bulimia. In obesity treatment, psychological interventions such as emotion regulation training would be helpful to reduce anxious emotions and thus decrease bulimic behavior.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Miller AL, Lumeng JC. Pathways of association from stress to obesity in early childhood. Obesity. 2018;26(7):1117–24.

Berkowitz RI, Moore RH, Faith MS, Stallings VA, Stunkard AJ. Identification of an obese eating style in 4-year-old children born at high and low risk for obesity. Obesity. 2012;18(3):505–12.

Campbell IC, Mill J, Uher R, Schmidt U. Eating disorders, gene–environment interactions and epigenetics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):784–93.

Danese A, Tan M. Childhood maltreatment and obesity: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(5):544–54.

Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T, Tomlinson M. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):1–31.

Shin SH, Miller DP. A longitudinal examination of childhood maltreatment and adolescent obesity: results from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) Study. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(2):84–94.

Richardson AS, Dietz WH, Gordon-Larsen P. The association between childhood sexual and physical abuse with incident adult severe obesity across 13 years of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9(5):351–61.

Smith HA, Markovic N, Danielson ME, Matthews A, Youk A, Talbott EO, Larkby C, Hughes T. Sexual abuse, sexual orientation, and obesity in women. J Womens Health. 2010;19(8):1525–32.

Matthews KA, Chang Y-F, Thurston RC, Bromberger JT. Child abuse is related to inflammation in mid-life women: role of obesity. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:29–34.

Katharine H, Leonie C, Michael D, Sally M, James S, Amanda B. The association between maltreatment in childhood and pre-pregnancy obesity in women attending an antenatal clinic in Australia. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51868.

Amianto F, Spalatro AV, Rainis M, Andriulli C, Lavagnino L, Abbate-Daga G, Fassino S. Childhood emotional abuse and neglect in obese patients with and without binge eating disorder: personality and psychopathology correlates in adulthood. Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:692–9.

Hornor G. Emotional maltreatment. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26(6):436–42.

Viola TW, Salum GA, Kluwe-Schiavon B, Sanvicente-Vieira B, Levandowski ML, Grassi-Oliveira R. The influence of geographical and economic factors in estimates of childhood abuse and neglect using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: a worldwide meta-regression analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;51:1–11.

Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal pathways linking child maltreatment, emotion regulation, peer relations, and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010;51(6):706–16.

Simon NM, Herlands NN, Marks EH, Mancini C, Stein MB. Childhood maltreatment linked to greater symptom severity and poorer quality of life and function in social anxiety disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010;26(11):1027–32.

Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(4):244–52.

Cole DA, Dukewich TL, Roeder K, Sinclair KR, McMillan J, Will E, Bilsky SA, Martin NC, Felton JW. Linking peer victimization to the development of depressive self-schemas in children and adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2014;42(1):149–60.

Bruce LC, Heimberg RG, Blanco C, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Childhood maltreatment and social anxiety disorder: implications for symptom severity and response to pharmacotherapy. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(2):132–9.

Gibb BE, Chelminski I, Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatients. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(4):256–63.

Calvete E. Emotional abuse as a predictor of early maladaptive schemas in adolescents: contributions to the development of depressive and social anxiety symptoms. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(4):735–46.

Roberts RE, Strawbridge WJ, Deleger S, Kaplan GA. Are the fat more jolly? Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):169–80.

Kasen S, Cohen P, Chen H, Must A. Obesity and psychopathology in women: a three decade prospective study. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32(3):558–66.

Scott KM, McGee MA, Wells JE, Oakley Browne MA. Obesity and mental disorders in the adult general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(1):97–105.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, Miglioretti DL, Crane PK, van Belle G, Kessler RC. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):824–30.

Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34(3):407–19.

Schag K, Schönleber J, Teufel M, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Food-related impulsivity in obesity and Binge Eating Disorder – a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2013;14(6):477–95.

Gropper SS, Simmons KP, Connell LJ, Ulrich PV. Changes in body weight, composition, and shape: a 4-year study of college students. Physiol Appl Nutr Metab. 2012;37(6):1118–23.

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Jia G, Story M, Haines J, Eisenberg M. Obesity, disordered eating, and eating disorders in a longitudinal study of adolescents: how do dieters fare 5 years later? J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(4):559–68.

Eddy KT, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Thompson-Brenner H, Herzog DB, Brown TA, Ludwig DS. Eating disorder pathology among overweight treatment-seeking youth: clinical correlates and cross-sectional risk modeling. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2360–71.

Levinson CA, Zerwas S, Calebs B, Forbush K, Kordy H, Watson H, Hofmeier S, Levine M, Crosby RD, Peat C, et al. The core symptoms of bulimia nervosa, anxiety, and depression: a network analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017;126(3):340–54.

Wilkinson LL, Rowe AC, Bishop RJ, Brunstrom JM. Attachment anxiety, disinhibited eating, and body mass index in adulthood. Int J Obes. 2010;34(9):1442–5.

Sawaoka T, Barnes RD, Blomquist KK, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Social anxiety and self-consciousness in binge eating disorder: associations with eating disorder psychopathology. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):740–5.

Ostrovsky NW, Swencionis C, Wylie-Rosett J, Isasi CR. Social anxiety and disordered overeating: an association among overweight and obese individuals. Eat Behav. 2013;14(2):145–8.

Shakory S, Van Exan J, Mills JS, Sockalingam S, Keating L, Taube-Schiff M. Binge eating in bariatric surgery candidates: the role of insecure attachment and emotion regulation. Appetite. 2015;91:69–75.

Araujo DMR, Santos GFDS, Nardi AE. Binge eating disorder and depression: a systematic review. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2–2):199–207.

Rosenbaum DL, White KS. The relation of anxiety, depression, and stress to binge eating behavior. J Health Psychol. 2015;20(6):887–98.

Maunder RG, Hunter JJ, Le TL. Insecure attachment and trauma in obesity and bariatric surgery. In: Sockalingam S, Hawa R, editors. Psychiatric care in severe obesity: an interdisciplinary guide to integrated care. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 37–48.

Banducci AN, Lejuez CW, Dougherty LR, MacPherson L. A prospective examination of the relations between emotional abuse and anxiety: moderation by distress tolerance. Prev Sci. 2017;18(1):20–30.

Cisler JM, Olatunji BO. Emotion regulation and anxiety disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(3):182–7.

Badrinath P, El-Rufaie O, Ghubach R, Moselhy HF, Sabri S, Yousef S, Zoubeidi T. The association of depression and anxiety with unhealthy lifestyle among United Arab Emirates adults. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2012;21(2):213–9.

Taube-Schiff M, Van Exan J, Tanaka R, Wnuk S, Hawa R, Sockalingam S. Attachment style and emotional eating in bariatric surgery candidates: the mediating role of difficulties in emotion regulation. Eat Behav. 2015;18:36–40.

Casagrande M, Boncompagni I, Forte G, Guarino A, Favieri F. Emotion and overeating behavior: effects of alexithymia and emotional regulation on overweight and obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(5):1333–45.

Annesi JJ, Mareno N, Mcewen K. Psychosocial predictors of emotional eating and their weight-loss treatment-induced changes in women with obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2016;21(2):1–7.

ZHANG M. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of CTQ-SF. Chin J Public Health. 2011;27(05):669–70.

Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–90.

Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(8):1132–6.

Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36(3):340–8.

Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Parental detection of youth’s self-harm behavior. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2008;38(1):60–73.

Kin-Wing SC, Chee-Wing W, Kit-Ching W, Heung-Chun GC. A study of psychometric properties, normative scores and factor structure of beck anxiety inventory chinese version. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2002;01:4–6.

Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893–7.

Muntingh AD, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Marwijk HW, Spinhoven P, Penninx BW, van Balkom AJ. Is the Beck Anxiety Inventory a good tool to assess the severity of anxiety? A primary care study in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:66.

Fydrich T, Dowdall D, Chambless DL. Reliability and validity of the beck anxiety inventory. J Anxiety Disord. 1992;6(1):55–61.

Lu ML, Che HH, Chang SW, Shen WW. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Chin Ment Health J. 2011;25(06):476–80.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8(1):77–100.

Kühner C, Bürger C, Keller F, Hautzinger M. Reliability and validity of the Revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). Results from German samples. Nervenarzt. 2007;78(6):651–6.

Whisman MA, Perez JE, Ramel W. Factor structure of the Beck Depression Inventory—Second Edition (BDI-ii) in a student sample. J Clin Psychol. 2000;56(4):545–51.

Zheng Y, Kang Q, Huang J, Jiang W, Liu Q, Chen H, Fan Q, Wang Z, **ao Z, Chen J. The classification of eating disorders in China: a categorical model or a dimensional model. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(6):712–20.

Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord. 1983;2(2):15–34.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol. 2003;88(5):879–903.

Hayes AF. Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. 2013;1:20.

Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press; 2013.

Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van Ijzendoorn MH. The universality of childhood emotional abuse: a meta-analysis of worldwide prevalence. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2012;21(8):870–90.

Hemmingsson E, Johansson K, Reynisdottir S. Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15(11):882–93.

Chamberland C, Fallon B, Black T, Trocmé N. Emotional maltreatment in Canada: prevalence, reporting and child welfare responses (CIS2). Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(10):841–54.

Sun J, Liu Q, Yu S. Child neglect, psychological abuse and smartphone addiction among Chinese adolescents: the roles of emotional intelligence and co** style. Comput Hum Behav. 2019;90(JAN.):74–83.

Chen YL, Liu X, Huang Y, Yu H-J. Association between child abuse and health risk behaviors among Chinese college students. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26(5):1–8.

Huang Q, Zhao X, Lin H. Childhood Maltreat: an investigation among the 335 senior high school students. China J Health Psychol. 2006;14(1):97–9.

Wolfe DA, McIsaac C. Distinguishing between poor/dysfunctional parenting and child emotional maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(10):802–13.

Hamarman S, Bernet W. Evaluating and reporting emotional abuse in children: parent-based, action-based focus aids in clinical decision-making. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(7):928–30.

Hamarman S, Pope KH, Czaja SJ. Emotional abuse in children: variations in legal definitions and rates across the United States. Child Maltreat. 2002;7(4):303–11.

Trickett PK, Mennen FE, Kim K, Sang J. Emotional abuse in a sample of multiply maltreated, urban young adolescents: issues of definition and identification. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(1):27–35.

Sanders J, Munford R, Thimasarn-Anwar T, Liebenberg L, Ungar M. The role of positive youth development practices in building resilience and enhancing wellbeing for at-risk youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;42:40–53.

Flores E, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Predictors of resilience in maltreated and nonmaltreated Latino children. Dev Psychol. 2005;41(2):338.

Arslan G. Psychological maltreatment, emotional and behavioral problems in adolescents: the mediating role of resilience and self-esteem. Child Abuse Negl. 2016;52:200–9.

Zaff JF, Hair EC. Positive development of the self: Self-concept, self-esteem, and identity. In: Well-being: Positive development across the life course. edn. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. p. 235–51.

Karakuş Ö. Relation between childhood abuse and self esteem in adolescence. J Hum Sci. 2012;9(2):753–63.

Goldsmith RE, Freyd JJ. Awareness for emotional abuse. J Emot Abus. 2005;5(1):95–123.

Zhao G, Ford ES, Dhingra S, Li C, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Depression and anxiety among US adults: associations with body mass index. Int J Obes. 2009;33(2):257–66.

Godart NT, Flament MF, Lecrubier Y, Jeammet P. Anxiety disorders in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: co-morbidity and chronology of appearance. Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15(1):38–45.

Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2215–21.

Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. 2019;33(2):72–89.

Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11):887–94.

Dallman MF, Pecoraro NC, la Fleur SE. Chronic stress and comfort foods: self-medication and abdominal obesity. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(4):275–80.

Nieuwenhuizen AG, Rutters F. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal-axis in the regulation of energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2008;94(2):169–77.

Adam TC, Epel ES. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiol Behav. 2007;91(4):449–58.

Yannakoulia M, Panagiotakos DB, Pitsavos C, Tsetsekou E, Fappa E, Papageorgiou C, Stefanadis C. Eating habits in relations to anxiety symptoms among apparently healthy adults. A pattern analysis from the ATTICA Study. Appetite. 2008;51(3):519–25.

Slochower J, Kaplan SP. Anxiety, perceived control, and eating in obese and normal weight persons. Appetite. 1980;1(1):75–83.

Paykel ES. Depression and appetite. J Psychosom Res. 1977;21(5):401–7.

Appelhans BM, Whited MC, Schneider KL, Ma Y, Oleski JL, Merriam PA, Waring ME, Olendzki BC, Mann DM, Ockene IS, et al. Depression severity, diet quality, and physical activity in women with obesity and depression. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):693–8.

Stice KS. Bearman: body-image and eating disturbances prospectively predict increases in depressive symptoms in adolescent girls: a growth curve analysis. Dev Psychol. 2001;37(5):597–607.

Svaldi J, Caffier D, Tuschencaffier B. Emotion suppression but not reappraisal increases desire to binge in women with binge eating disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(3):188–90.

Gianini LM, White MA, Masheb RM. Eating pathology, emotion regulation, and emotional overeating in obese adults with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav. 2013;14(3):309–13.

Zijlstra H, van Middendorp H, Devaere L, Larsen JK, van Ramshorst B, Geenen R. Emotion processing and regulation in women with morbid obesity who apply for bariatric surgery. Psychol Health. 2012;27(12):1375–87.

Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Giel KE. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity–a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:125–34.

Gross JJ, Barrett LF. Emotion generation and emotion regulation: one or two depends on your point of view. Emot Rev. 2011;3(1):8.

Pinaquy S, Chabrol H, Simon C, Louvet J-P, Barbe P. Emotional eating, alexithymia, and binge-eating disorder in obese women. Obes Res. 2003;11(2):195–201.

Ricca V, Castellini G, Sauro CL, Ravaldi C, Lapi F, Mannucci E, Rotella CM, Faravelli C. Correlations between binge eating and emotional eating in a sample of overweight subjects. Appetite. 2009;53(3):418–21.

Nowakowski ME, McFarlane T, Cassin S. Alexithymia and eating disorders: a critical review of the literature. J Eat Disord. 2013;1(1):21.

Wilkinson LL, Rowe AC, Robinson E, Hardman CA. Explaining the relationship between attachment anxiety, eating behaviour and BMI. Appetite. 2018;127:214–22.

Cooper PJ, Bowskill R. Dysphoric mood and overeating. Br J Clin Psychol. 1986;25(2):155–6.

Berking MWB. Affect regulation training. Vol. 2. 2014.

Volkaert B, Wante L, Vervoort L, Braet C. ‘Boost Camp’, a universal school-based transdiagnostic prevention program targeting adolescent emotion regulation; evaluating the effectiveness by a clustered RCT: a protocol paper. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):904.

Debeuf T, Verbeken S, Boelens E, Volkaert B, Van Malderen E, Michels N, Braet C. Emotion regulation training in the treatment of obesity in young adolescents: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):153.

Federico A, Spalatro AV, Giorgio I, Enrica M, Abbate Daga G, Secondo F. Personality and psychopathology differences between bariatric surgery candidates, subjects with obesity not seeking surgery management, and healthy subjects. Eat Weight Disord. 2019;24(4):623–31.

Vermetten E, Schmahl C, Lindner S, Loewenstein RJ, Bremner JD. Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):630.

Frodl T, Reinhold E, Koutsouleris N, Reiser M, Meisenzahl EM. Interaction of childhood stress with hippocampus and prefrontal cortex volume reduction in major depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(13):799–807.

Teicher MH, Anderson CM, Polcari A. Childhood maltreatment is associated with reduced volume in the hippocampal subfields CA3, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(9):E563-572.

Choi J, Jeong B, Rohan ML, Polcari AM, Teicher MH. Preliminary evidence for white matter tract abnormalities in young adults exposed to parental verbal abuse. Biol Psychiat. 2009;65(3):227–34.

Choi J, Jeong B, Polcari A, Rohan ML, Teicher MH. Reduced fractional anisotropy in the visual limbic pathway of young adults witnessing domestic violence in childhood. Neuroimage. 2012;59(2):1071–9.

Schienle A, Schäfer A, Hermann A, Vaitl D. Binge-eating disorder: reward sensitivity and brain activation to images of food. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65(8):654–61.

Brooks SJ, O’Daly OG, Uher R, Friederich HC, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Williams SC, Schiöth HB, Treasure J, Campbell IC. Differential neural responses to food images in women with bulimia versus anorexia nervosa. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22259.

Skunde M, Walther S, Simon JJ, Wu M, Bendszus M, Herzog W, Friederich HC. Neural signature of behavioural inhibition in women with bulimia nervosa. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2016;41(5):E69-78.

Zhang H, Liu Z, Zheng H, Xu T, Liu L, Xu T, Yuan T-F, Han X. The influence of childhood emotional abuse on adult obesity. 2021.

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhang Yi for contributing to the study, Wu Tong for data collection, and all participants who participated in this study. The previous version of this manuscript “The Influence of Childhood Emotional Abuse On Adult Obesity” [113] had been preprinted in the research square.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Department of Bariatric & Metabolic Surgery, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, Shanghai, China. National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82370901): The Neural Mechanism of Amygdala in Food Craving to improve relapse of obesity after bariatric surgery via GLP-1 / GLP-1R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hongwei Zhang: funding acquisition; resources administration. Ziqi Liu: formal analysis; data curation; visualization and writing the original draft. Hui Zheng: conceptualization; methodology and project administration. Ting Xu: data curation and resources. Lin Liu: data curation and resources. Tao Xu: project administration and supervision. Ti-Fei Yuan: project administration; supervision and review and editing. **aodong Han: conceptualization; funding acquisition; project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was supported by a clinical retrospective study of Shanghai Jiaotong University Affiliated Sixth People’s Hospital, “The middle-term efficacy of RYGB and SG in improving metabolic disorders”, Grant Number: YNHG201912. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Sixth People’s Hospital, NO 2020-219-(1). All procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki. All participant had signed the informed consent form.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Liu, Z., Zheng, H. et al. Multiple mediation of the association between childhood emotional abuse and adult obesity by anxiety and bulimia – a sample from bariatric surgery candidates and healthy controls. BMC Public Health 24, 653 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18015-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18015-w