Abstract

Background

Access to fertility treatments is considered a reproductive right, but because of the quarantine due to the coronavirus pandemic most infertility treatments were suspended, which might affect the psychological and emotional health of infertile patients. Therefore, this study was conducted to review the mental health of infertile patients facing treatment suspension due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Methods

This study was conducted based on the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guideline. The Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane library databases were searched by two independent researchers, without time limitation until 31 December 2022. All observational studies regarding the mental health of infertile patients facing treatment suspension including anxiety, depression, and stress were included in the study. Qualitative studies, editorials, brief communications, commentaries, conference papers, guidelines, and studies with no full text were excluded. Quality assessment was carried out using Newcastle–Ottawa Scale by two researchers, independently. The random effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence of mental health problems. Meta-regression and subgroup analysis were used to confirm the sources of heterogeneity.

Results

Out of 681 studies, 21 studies with 5901 infertile patients were systematically reviewed, from which 16 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The results of all pooled studies showed that the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress in female patients was 48.4% (95% CI 34.8–62.3), 42% (95% CI 26.7–59.4), and 55% (95% CI 45.4–65), respectively. Additionally, 64.4% (95% CI 50.7–76.1) of patients wished to resume their treatments despite the coronavirus pandemic.

Conclusion

Treatment suspension due to the coronavirus pandemic negatively affected the mental health of infertile patients. It is important to maintain the continuity of fertility care, with special attention paid to mental health of infertile patients, through all the possible measures even during a public health crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infertility is a worldwide health concern, affecting approximately 168 million people of reproductive age, globally [1]. Infertility is defined as the inability to consume a child after 12 or more months of unprotected intercourse [1]. Involuntary childlessness can be considered a life crisis with a great impact on physical, social, emotional, and psychological aspects of life [1,2,3,4]. Social stigma, domestic violence, divorce, decrease in self-esteem, stress, anxiety, and depression are amongst the adverse psychosocial effect of infertility [1, 4,5,6]. Even though fertility treatments have evolved during the past decades, these procedures often cause patients physical and or mental distress [2, 5, 7]. The emotional tension experienced by infertile women may lead to changes in endocrine system regulation and probably result in adverse pregnancy outcomes [5, 6, 8].

A pandemic occurs when a disease spread worldwide, passing international borders and infecting a large number of people [9]. Pandemics and the measures that are taken to control or suppress them such as patient isolation, social distancing, and quarantine can increase mental distress and perceived risk of disease, which leads to psychological consequences including stress, anxiety, depression, delirium, and even post-traumatic stress disorder [10].

In December 2019, cases of infection with the new coronavirus were reported in Wuhan, China [11]. Soon after, the virus was spread across the world, and in May 2020 it was declared a pandemic by World Health Organization [12, 13]. The majority of people infected with this virus through droplet transmission have mild to moderate symptoms, but in some cases, the severity of symptoms may lead to death [13]. Until now 767,984,989 people were infected by the virus and more than 6.9 million people lost their lives [14]. In addition to physical effects, coronavirus can affect the psychological well-being of individuals [11, 24,25].

The results of systematic reviews indicate that treatment suspension or postponement has a negative effect on patients' mental health. In a systematic review on the mental health and treatment impacts of covid-19 on neurocognitive disorders, an increase in mental health disorders in patients whose treatments were suspended due to the coronavirus pandemic was reported [26]. Similarly, another systematic review reported a negative relationship between mental health and treatment suspension in cancer patients [27].

As it was mentioned, both infertility and the coronavirus pandemic have negative mental outcomes, so that if the impact of treatment suspension is added, the severity of adverse mental health effects on infertile patients would be increased. Although different studies have been conducted regarding the relationship between treatment suspension due to the coronavirus pandemic and the mental health of infertile patients; to the best of our knowledge, no systematic review has been conducted in this relation. It is noteworthy that two systematic reviews have been published with respect to fertility treatment during the Covid-19 pandemic. One systematic review examined the challenges of oncofertility and fertility preservation treatment and the importance of telemedicine during the Covid-19 pandemic [28]. Another systematic review was conducted on the psychological impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on fertility care, and its finding suggested that the covid-19 pandemic causes negative psychological impacts on fertility care [29]; but because of the heterogeneity of studies, the researchers were not able to perform a meta-analysis. In their review, patients were also heterogeneous, with some studies conducted on patients receiving treatment, and some on patients whose treatment was halted or postponed.

Based on the studies conducted prior to the Covid-19 pandemic [2, 30, 31], it is clear that infertile patients suffer from psychological disorders resulted from their infertility. Also, as it was mentioned, systematic reviews on patients other than those who undergo fertility care, suggest that suspension or postponement of treatment has a negative effect on patients' mental health [26, 27]. Therefore, it seems that infertile patients who face treatment suspension or postponement can be at higher risk for mental disorders. Consequently, the mental health status of an infertile patient, who is undergoing fertility treatment might be different from those who experienced treatment postponement. This difference can affect their quality of life and satisfaction with treatment. Therefore, it was decided to conduct a systematic review in this regard. On the other hand, since meta-analyses help with improvement in precision by summarizing and synthesizing of quantitative data from independent yet comparable studies included in a systematic review [32,33,34,35], it will be easier and more practical for the audiences to grasp the results of different studies by viewing the results of meta-analysis. In order to reach a precise, clear and summarized result from the findings of the reviewed studies, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to assess the mental health of infertile patients facing treatment suspension due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

To do this study, MOOSE Guidelines for Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Observational Studies was followed [35]. The protocol is registered in PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) under the code of CRD42023399725. Also, the study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (Code of ethics: IR.MUMS.NURSE.REC.1401.056).

Search strategy and data sources

Two researchers (EI, AY), independently, searched PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, Embase, and Cochrane library databases using keywords including coronavirus, covid-19, sars-cov-2, infertility, assisted reproductive technique, psychological distress, stress, anxiety, depression, psychological status, psychological problems/issues, mental health, suspension, and postponement with no time limit until 31 December 2022 (see Additional File 1). Search results of each database was imported to a library created by Endnote reference management software version 9. The software was also used to manage the studies, including identification and removal of duplicated studies, and screening of the titles and abstracts. References of articles which met the inclusion criteria were also searched manually. Since all the relevant articles found by manual search were already included in the study, no records were added by manual search.

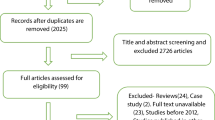

Using appropriate keywords, the search of different databases was conducted. At first, duplicate articles were removed. In the next step, the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were carefully reviewed and the irrelevant articles were excluded. Then the full text of the remaining articles was sought, and articles without access to the full text were excluded. It must be noted that before the exclusion of articles with no access to the full text (n = 1), the corresponding author was reached and she provided us with the full text. Finally, the full text of the remaining articles was reviewed, and those articles that met our inclusion criteria were reviewed in the data extraction process. Two researchers (EI, AY), independently, assessed inclusion and exclusion criteria for each study.

Inclusion criteria

-

Observational studies including cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort studies regarding the mental health of infertile patients facing treatment suspension,

-

Studies published in the English language

-

PECO was as follows:

-

Participants: Infertile patients seeking treatment

-

Exposure: Treatment suspension due to the Covid-19 pandemic

-

Comparator: None

-

Outcomes: Mental health of infertile patients including anxiety, depression, and stress.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

No access to the full text of the articles

-

Secondary research including systematic reviews, narrative reviews, sco** and rapid reviews as well as other types of articles including qualitative research reports, commentaries and letters to the editor

-

Theses or conference abstracts as well as guidelines

-

Observational studies which did not follow PECO criteria such as studies on infertile couples with ongoing treatment or infertile couples experiencing pregnancy during the Covid-19 pandemic, or studies which assessed outcomes other than those specified in PECO.

-

Languages other than English

Quality assessment

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used for the quality assessment of the studies. The scale is consisted of three sections including selection, comparability, and outcome (exposure in case–control studies). The maximum score for the scale is nine stars, and for each sections including selection, comparability, and outcome respectively is four, two, and three stars [36, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Also, 16 studies were included in the meta-analysis [52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60, 61, 63,64,65,66, 68, 70, 71]. The process of study selection is seen in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

There was diversity in the region of the studies. Seven studies were from Europe (France [56], Italy [52, 68, 71], Portugal [25], Serbia [59], and Spain [65]); four were from Asia (China [67, 70] and India [54, 55]); four studies were from the Middle East (Iran [60], Israel [63], and Turkey [61, 64]) and six studies were conducted in Canada and/or USA [53, 57, 58, 62, 66, 69]. Except for the study of Dong et al. (2021) and Rasekh Jahromi et al. (2022), which were case–control studies [60, 70], all of the studies had cross-sectional designs. All the participants (n: 5901) were infertile patients seeking treatment during the covid-19 pandemic and their treatment plans were either halted or postponed; the majority of whom were females (90 Percent, n: 5306); and 8.5 percent (n: 504) of the participants were male. Also, 91 participants (1.5 percent) did not mention their gender (Table 1).

Due to the social distancing practice, except for two studies [55, 70], all of the studies were conducted as online surveys [25, 52,53,54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69, 71]. Also, eight studies used Google forms [52, 58, 60, 61, 63, 65, 68, 69], two used REDCap [62, 66], and two used the SurveyMonkey.com platform [57, 71]. Others did not specify the online measures [25, 53,54,55,56, 59, 64, 67, 70]. In terms of data collection tools, except for two studies that used self-structured questionnaires [55, 68], 19 studies used validated instruments [25, 52,53,54, 56, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, 69,70,71]. Regarding using specific tools for Covid-19, only two studies used covid-19 related questionnaires, including the Fear of Covid-19 Scale (FCV-19S) and the Covid-19 Anxiety Score [63, 64] (Table 1).

Using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale, seven studies were considered of high quality [52, 57, 60, 65, 67, 69, 71], and 14 studies were of moderate quality [25, 53,54,55,56, 58, 59, 61,62,63,64, 66, 68, 70] and In regards to quality assessment of cross-sectional studies, all articles (n = 19) [25, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59, 61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69, 71] achieved maximum score (three stars) in outcome section. While 74% of articles (n = 14) [52,53,54, 56,57,58, 62, 63, 65,66,67,68,69, 71] achieved maximum score in comparability section and only 10.5% (n = 2) [52, 69] received maximum score in selection section. As for case–control studies (n = 2) [60, 70], only one study achieved maximum score in Comparability and Exposure section (two and three stars respectively) [60], and both [60, 70] achieved three out of four in selection section. (see Additional File 3).

Based on the findings of this review, the rate of anxiety in infertile women whose treatment was suspended or postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic ranged from 11 to 72 percent. Also, the prevalence of depression varied from 14 to 77 and the prevalence of stress ranged from 38.9 to 64 percent, which is discussed in more detail. Also, it is important to note that, since the majority of the studies under review did not include male patients in their analysis, meta-analysis could not be performed on male anxiety, depression, and stress due to lack of data.

Anxiety

Anxiety was the outcome, which was measured in 15 studies [25, 52, 54,55,56,57,58, 62, 64,65,66,67,68, 70, 71]. Different tools including General Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI, STAI-5, and STAI-6), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 Items (DASS-21) were used in order to measure infertile patients' anxiety. Although Galhardo et al. (2021) found no significant differences regarding anxiety scores between infertile patients with treatment suspension during the coronavirus pandemic and an infertility reference sample [25], Lablanche et al. (2022) reported that the rate of anxiety was much higher than those expected in the infertile population [56]. Two studies reported an increase in anxiety rate in patients who were in confinement [65, 67]. Fear of covid-19 infection and exposure to covid-19 related news were reported to have a negative effect on patients' anxiousness [52, 54]. Being female [52, 71], having previous IVF cycles [52, 67], and older age [52, 54, 64] were also found to increase the anxiety score.

The pooled prevalence of anxiety in infertile women

Out of the 15 studies mentioned above, twelve studies reported either the number or percentage of women affected with anxiety during the treatment suspension period. The prevalence of anxiety varied from study to study and it was reported from a low percent of 11 to a high percent of 72. The estimated pooled prevalence was 48.4% (95% CI, 34.8–62.3) (Fig. 2). The I2 index was 98.01, which indicated high heterogeneity. Meta-regression was conducted and the sample size was considered as the source of heterogeneity (p < 0.001). Publication bias was not observed (Egger test p-value: 0.30).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of anxiety

The highest pooled prevalence estimate was calculated across the two studies using the STAI (40, 51), which was 72.1% (95% CI, 68.7–75.4). The lowest estimate was calculated for the three studies using the GAD-7 (32, 39, 45), which was 51.3% (95% CI 48.2–54.4). The heterogeneity was not significant between subgroups (P = 0.64) (Table 2).

Depression

Depression was measured in 10 studies [25, 52, 53, 55, 57, 60, 61, 65, 66, 70]. Different tools including Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8 and PHQ-9), Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 Items (DASS-21) were used in order to measure infertile patients' depression. Although Galhardo et al. (2021) found no significant differences regarding depression scores between infertile patients with treatment suspension during the coronavirus pandemic and an infertility reference sample [25], Dillard et al. (2022) reported that depressive symptoms were greater during the pandemic [69] and Biviá-Roig et al. (2021) reported an increase in depression score in patients who were in confinement [65]. Also, Rasekh Jahromi et al. (2022) reported that infertile women whose treatment was delayed were more depressed than those who were not under treatment[60]. It was reported that women were more depressed than men [52, 71]. Rasekh Jahromi et al. (2022) and Sahin et al. (2021) both reported a positive correlation between depression and hopelessness [60, 61]; in contrast to Sahin et al. (2021) who found that women with secondary infertility had higher mean depression score [61], Rasekh Jahromi et al. (2022) reported that women with primary infertility were more depressed [60].

The pooled prevalence of depression in infertile women

Out of the 10 studies, nine reported either the number or percentage of women affected with depression during the treatment suspension period. The prevalence of depression varied from study to study and it was reported from a low rate of 14 to a high rate of 77 percent. The estimated pooled prevalence was 42% (95% CI, 26.7–59.4) (Fig. 3). The I2 index was 97.70, which indicated high heterogeneity. Meta-regression was conducted and sample size and mean age were considered as the source of heterogeneity (p < 0.001). Publication bias was not observed (Egger test p-value: 0.09).

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of depression

To assess depression, PHQ-9 (32,39,41) with a pooled prevalence of 37.4 (95% CI, 23.8–53.3) was used by three studies. Also, BDI (48, 49) and HADS (34,35) respectively with a pooled prevalence of 62.9 (95% CI, 43.2–79) and 28.2 (95% CI, 14.8–47.2) were used by two studies. Furthermore, PHQ-8 (45) and researcher-made tool (43) each were used in one study. The subgroup analysis suggested evidence of differential prevalence estimates between tools used to assess depression (P = 0.001) (Table 3).

Stress

Eleven studies reported stress in infertile patients whose treatments were either suspended or postponed [25, 54, 56,57,58,59, 62, 63, 69,70,71]. Perceived stress scale (PSS-10, PSS-4), Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R), and Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 Items (DASS-21) were used to assess stress. Dillard et al. (2022) and Galhardo et al. (2021) reported the mean score of the perceived stress scale-10 in their studies as 19.9 and 20.9 respectively [25, 69]. Three studies reported the prevalence of stress [56, 57, 63]. Higher levels of stress were observed in patients whose treatments were suspended or postponed due to the covid-19 pandemic [69, 70]. Even though two studies reported no significant relationship between demographic characteristics of the patients and stress [58, 69], others reported that age [56, 57, 63], duration of infertility [54, 57], anxiety levels of the patients [56, 58, 62], support system [54, 59], and co** strategies [57, 59] are associated with a higher level of stress.

The pooled prevalence of stress in infertile women

Out of the 11 studies, three reported either the number or percentage of women affected with stress during the treatment suspension period. The prevalence of stress varied from study to study and it was reported from a low rate of 50 to a high rate of 64 percent. The estimated pooled prevalence was 55% (95% CI, 45.4–65) (Fig. 4). The I2 index was 90.99, which indicated high heterogeneity. Publication bias was not observed (Egger test p-value: 0.25). Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were not undertaken because of the small number of studies (n:3) [72].

Other findings

The pooled prevalence of patients who wished to resume treatment

Ten studies reported either the number or percentage of patients who wished to resume infertility treatment [52, 54,55,56,57,58, 63, 64, 66, 71]. The prevalence varied from study to study and it was reported from a low rate of 33 to a high rate of 98 percent. The estimated pooled prevalence was 64.4% (95% CI, 50.7–76.1) (Fig. 5). The I2 index was 97.89, which indicated high heterogeneity. Meta-regression was conducted and the sample size was considered as the source of heterogeneity (p < 0.001). Publication bias was not observed (Egger test p-value: 0.21).

Discussion

The results of this review showed that treatment suspension due to the coronavirus pandemic increased the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress in female patients. Based on the findings, the rate of anxiety in infertile women whose treatment was suspended or postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic ranged from 11 to 72 percent. This wide range may be due to variations in tools and cut-off points that were used to measure infertile women's anxiety. A systematic review on the mental health of the general population during the coronavirus pandemic; reported anxiety rates of 6.33%. This finding in comparison to ours, suggests that infertile patients who faced treatment suspension during the covid-19 pandemic had higher rates of anxiety [59, 64, 66, 68, 69, 75]. In one study a positive relationship was reported between mental distress and the time spent on the coronavirus-related news in infertile patients facing treatment postponement [52]. This positive relationship was also observed in the general population [59, 66, 69, 75]. Many infertile patients felt that treatment suspensions were unfair and made them angry [55, 58, 64]. Closure of fertility treatment centers also decreased the quality of life of patients [53, 65, 68]; this is aligned with the findings of a systematic review on the general population [77]. Delay or suspension of treatment due to the coronavirus pandemic was found to be related to increased levels of mental health problems in other patients too. A systematic review reported an increase in mental disorders in patients with neurocognitive disorders whose treatments were suspended [26]. A negative relationship between mental health and treatment suspension in cancer patients was also reported in another systematic review [27]. Maintaining social relationships, receiving support, kee** fit, and having a daily routine could help infertile patients to cope with this situation better [24, 62, 63].

Based on our results 64.4% percent of infertile patients wished to resume their treatment despite the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. Reports of one study showed that only 6% of infertile patients agreed with delaying their treatment [74]. A cross-sectional study also reported that only 28% of infertile patients were concerned about maternal–fetal transmission of the virus in case of infection during treatment [78]. Based on these findings and in accordance with studies on providing fertility care during covid-19 pandemic [79, 80], it is important to maintain the continuity of fertility care, with special attention paid to mental health of infertile patients, through all the possible measures including virtual care and telemedicine. To substitute the cancelled appointments and ensure patient satisfaction, fertility treatment centers could arrange virtual appointments.

The main limitation of this study was the significant degree of heterogeneity across the studies, which should be taken into account when interpreting the data. The other limitation was that due to the lack of sufficient quantitative data in the reviewed studies, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis on the relationship between treatment suspension and mental health of infertile patients. Further research with a larger sample size using validated tools is recommended. Also, the short-term and long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic and treatment suspension on the mental health of infertile patients need to be investigated further.

One of the strengths of this study was that not only it measured the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress in infertile women whose treatment were postponed or suspended, but also compared those results in relation to the pre covid-19 pandemic mental health status of infertile women and those of general public during covid-19 pandemic. Also provided quantitative data on the prevalence of patients who wished to resume their treatment. Another strength of this study was the diversity in the included studies in geographical, and socio-economic terms.

Conclusion

Treatment suspension due to coronavirus pandemic can negatively affect the mental health of infertile patients. Personalized planning could improve infertile patients' mental health. It is important to maintain the continuity of fertility care, with special attention paid to mental health of infertile patients, through all the possible measures including virtual care. Fertility healthcare providers must involve patients in the decision-making process about their treatments even in a public health crisis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Assisted Reproductive Technology

- ASRM:

-

American society of reproductive medicine

- BDI:

-

Beck's Depression Inventory

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- DASS-21:

-

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 Items

- ESHRE:

-

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology

- FCV-19S:

-

Fear of Covid-19 Scale

- GAD-7:

-

General Anxiety Disorder

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- IES-R:

-

Impact of Event Scale-Revised

- IVF:

-

In Vitro Fertilization

- MHI:

-

Mental Health Inventory

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- STAI:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

References

world health organization Infertility. https://www.who.int/health-topics/infertility#tab=tab_1. Accessed 24 Sep 2021.

Ying L, Wu LH, Loke AY. The effects of psychosocial interventions on the mental health, pregnancy rates, and marital function of infertile couples undergoing in vitro fertilization: a systematic review. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:689–701.

Bright K, Dube L, Hayden KA, Gordon JL. Effectiveness of psychological interventions on mental health, quality of life and relationship satisfaction for individuals and/or couples undergoing fertility treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036030.

Abdollahpour S, Taghipour A, Mousavi Vahed SH, Latifnejad Roudsari R. The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy on stress, anxiety and depression of infertile couples: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;42:188–97.

Frederiksen Y, Farver-Vestergaard I, Skovgård NG, Ingerslev HJ, Zachariae R. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for psychological and pregnancy outcomes in infertile women and men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2014-006592.

Katyal N, Poulsen CM, Knudsen UB, Frederiksen Y. The association between psychosocial interventions and fertility treatment outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reproductive Biology. 2021;259:125–32.

Ebrahimzadeh Zagami S, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Janghorban R, Mousavi Bazaz SM, Amirian M, Allan HT. Infertile couples’ needs after unsuccessful fertility treatment: a qualitative study. J Caring Sci. 2019;8:95–104.

Hassanzadeh Bashtian M, Latifnejad Roudsari R, Sadeghi R. Effects of acupuncture on anxiety in Infertile women: a systematic review of the literature. J Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2017;5:842–8.

Phina NF. The classical definition of a pandemic is not elusive. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:540.

Huremovic D. Psychiatry of Pandemics: A Mental Health Response to Infection Outbreak, 1st ed. Psychiatry of Pandemics 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15346-5.

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, Vaisi-Raygani A, Rasoulpoor S, Mohammadi M, Rasoulpoor S, Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12992-020-00589-W.

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157–60.

World Health Organization Coronavirus. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1. Accessed 16 Aug 2022.

World Health Organization WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19). Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 16 Jun 2023.

**ong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64.

Sharifi F, Larki M, Latifnejad Roudsari R. COVID-19 outbreak as threat of violence against women. J Midwifery Reproductive Health. 2020;8:2376–9.

Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:531.

Anifandis G, Messini CI, Daponte A, Messinis IE. COVID-19 and fertility: a virtual reality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:157–9.

Alviggi C, Esteves SC, Orvieto R, et al. COVID-19 and assisted reproductive technology services: repercussions for patients and proposal for individualized clinical management. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18:45.

Larki M, Sharifi F, Manouchehri E, Latifnejad Roudsari R. Responding to the essential sexual and Reproductive Health needs for women during the COVID-19 pandemic: a Literature Review. Malaysian J Med Sci. 2021;28:8–19.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Patient management and clinical recommendations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic Patient management and clinical recommendations during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic *. 1–9. 2020.

The ESHRE COVID-19 Working group, Hambartsoumian E, Nouri K, et al. A picture of medically assisted reproduction activities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020:1–8.

Trinchant RM, Cruz M, Marqueta J, Requena A. Infertility and reproductive rights after the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:151–3.

Boivin J, Harrison C, Mathur R, Burns G, Pericleous-Smith A, Gameiro S. Patient experiences of fertility clinic closure during the COVID-19 pandemic: appraisals, co** and emotions. Hum Reprod. 2020;35:2556–66.

Galhardo A, Carolino N, Monteiro B, Cunha M. The emotional impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in women facing infertility. Psychol Health Med. 2021;1–7.

Dellazizzo L, Léveillé N, Landry C, Dumais A. Systematic review on the mental health and treatment impacts of COVID-19 on neurocognitive disorders. J Personalized Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/JPM11080746.

Dhada S, Stewart D, Cheema E, Hadi MA, Paudyal V. Cancer services during the COVID-19 pandemic: systematic review of Patient’s and Caregiver’s experiences. Cancer Manage Res. 2021;13:5875–87.

Voultsos PP, Taniskidou A-MI. Fertility treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Afr J Reprod Health. 2021;25:161–78.

Kirubarajan A, Patel P, Tsang J, Prethipan T, Sreeram P, Sierra S. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fertility care: a qualitative systematic review. Hum Fertility. 2021;1–8.

Kiani Z, Simbar M, Hajian S, Zayeri F, Shahidi M, Saei Ghare Naz M, Ghasemi V. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms in infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility Res Pract. 2020;6:7.

Kiani Z, Simbar M, Hajian S, Zayeri F. The prevalence of depression symptoms among infertile women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertility Res Pract. 2021;7:6.

Deeks J, Higgins JP, Altman D. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ WV, editor Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane, 2021;pp 1–649.

Barker TH, Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Falavigna M, Aromataris E, Munn Z. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: a guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21:189.

Schwarzer G, Rücker G. Meta-analysis of proportions. In: Evangelou E, Veroniki AA, editors. Meta-research. Methods in Molecular Biology. New York, NY: Humana; 2022. p. 159–72.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of Observational studies in Epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008.

Wu XY, Han LH, Zhang JH, Luo S, Hu JW, Sun K. The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12: e0187668.

Xu S, Wan Y, Xu M, Ming J, **ng Y, An F, Ji Q. The association between obstructive sleep apnea and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2015;15:105.

Jawad M, Vamos EP, Najim M, Roberts B, Millett C. Impact of armed conflict on cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Heart. 2019;105:1388–94.

Jenkins RH, Vamos EP, Taylor-Robinson D, Millett C, Laverty AA. Impacts of the 2008 Great recession on dietary intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activity. 2021;18:1–20.

Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Navarro-Santana M, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Cuadrado ML, García-Azorín D, Arendt-Nielsen L, Plaza-Manzano G. Headache as an acute and post-COVID-19 symptom in COVID-19 survivors: a meta-analysis of the current literature. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3820–5.

Hariyanto TI, Halim DA, Jodhinata C, Yanto TA, Kurniawan A. Colchicine treatment can improve outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;48:823–30.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synthesis Methods. 2010;1:97–111.

Saha S, Chant D, Mcgrath J. Meta-analyses of the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia: conceptual and methodological issues. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:55–61.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58.

Pacheco JPG, Bunevicius A, Oku A, et al. Pooled prevalence of depressive symptoms among medical students: an individual participant data meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:251.

Kiani Z, Fakari FR, Hakimzadeh A, Hajian S, Fakari FR, Nasiri M. Prevalence of depression in infertile men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:1972.

Pilania M, Yadav V, Bairwa M, Behera P, Gupta SD, Khurana H, Mohan V, Baniya G, Poongothai S. Prevalence of depression among the elderly (60 years and above) population in India, 1997–2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:832.

Hawcroft C, Hughes R, Shaheen A, Usta J, Elkadi H, Dalton T, Ginwalla K, Feder G. Prevalence and health outcomes of domestic violence amongst clinical populations in arab countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:315.

Chau SWH, Wong OWH, Ramakrishnan R, et al. History for some or lesson for all? A systematic review and meta-analysis on the immediate and long-term mental health impact of the 2002–2003 severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:670.

Ayano G, Shumet S, Tesfaw G, Tsegay L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of bipolar disorder among homeless people. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:731.

Barra F, La Rosa VL, Vitale SG, Commodari E, Altieri M, Scala C, Ferrero S. Psychological status of infertile patients who had in vitro fertilization treatment interrupted or postponed due to COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2020;0:1–8.

Gordon JL, Balsom AA. The psychological impact of fertility treatment suspensions during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0239253.

Jaiswal P, Mahey R, Singh S, Vanamail P, Gupta M, Cheluvaraju R, Sharma JB, Bhatla N. Psychological impact of suspension/postponement of fertility treatments on infertile women waiting during COVID pandemic. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2022;65:197–206.

Kaur H, Pranesh G, Rao K. Emotional impact of delay in fertility treatment due to COVID-19 pandemic. J Hum Reproductive Sci. 2020;13:317.

Lablanche O, Salle B, Perie M-A, Labrune E, Langlois-Jacques C, Fraison E. Psychological effect of COVID-19 pandemic among women undergoing infertility care, a French cohort – PsyCovART psychological effect of COVID-19: PsyCovART. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2022;51: 102251.

Lawson AK, McQueen DB, Swanson AC, Confino R, Feinberg EC, Pavone ME. Psychological distress and postponed fertility care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38:333–41.

Marom Haham L, Youngster M, Kuperman Shani A, Yee S, Ben-Kimhy R, Medina-Artom TR, Hourvitz A, Kedem A, Librach C. Suspension of fertility treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: views, emotional reactions and psychological distress among women undergoing fertility treatment. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;42:849–58.

Mitrović M, Kostić JO, Ristić M. Intolerance of uncertainty and distress in women with delayed IVF treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of situation appraisal and co** strategies. J Health Psychol. 201;135910532110499.

Rasekh Jahromi A, Daroneh E, Jamali S, Ranjbar A, Rahmanian V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on depression and hopelessness in infertile women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2022;43:495–501.

Şahin B, Şahin B, Karlı P, Sel G, Hatırnaz Ş, Kara OF, Tinelli A. Level of depression and hopelessness among women with infertility during the outbreak of COVID-19: a cross-sectional investigation. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2021;48:594.

Seifer DB, Petok WD, Agrawal A, Glenn TL, Bayer AH, Witt BR, Burgin BD, Lieman HJ. Psychological experience and co** strategies of patients in the Northeast US delaying care for infertility during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2021;19:66.

Ben-Kimhy R, Youngster M, Medina-Artom TR, Avraham S, Gat I, Marom Haham L, Hourvitz A, Kedem A. Fertility patients under COVID-19: attitudes, perceptions and psychological reactions. Hum Reprod (Oxford England). 2020;35:2774–83.

Tokgoz VY, Kaya Y, Tekin AB. The level of anxiety in infertile women whose ART cycles are postponed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2020;0:1–8.

Biviá-Roig G, Boldó-Roda A, Blasco-Sanz R, Serrano-Raya L, DelaFuente-Díez E, Múzquiz-Barberá P, Lisón JF. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyles and Quality of Life of Women with fertility problems: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2021;9:1–10.

Bortoletto P, Applegarth L, Josephs L, Witzke J, Romanski PA, Schattman G, Rosenwaks Z, Grill E. Psychosocial response of infertile patients to COVID-19-related delays in care at the epicenter of the global pandemic. Minerva Obstet Gynecol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-606X.21.04852-1.

Cao L-B, Hao Q, Liu Y, Sun Q, Wu B, Chen L, Yan L. Anxiety level during the second localized COVID-19 pandemic among quarantined infertile women: a cross-sectional survey in China. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:1–9.

Cirillo M, Rizzello F, Badolato L, De Angelis D, Evangelisti P, Coccia ME, Fatini C. The effects of COVID-19 lockdown on lifestyle and emotional state in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology: results of an Italian survey. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50:102079.

Dillard AJ, Weber AE, Chassee A, Thakur M. Perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic among women with infertility: correlations with Dispositional Optimism. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19: 2577.

Dong M, Wu S, Tao Y, Zhou F, Tan J. The impact of postponed fertility treatment on the sexual health of infertile patients owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.730994.

Esposito V, Rania E, Lico D, et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological status of infertile couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reproductive Biology. 2020;253:148–53.

Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyse. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2011.

Deng J, Zhou F, Hou W, Silver Z, Wong CY, Chang O, Huang E, Zuo QK. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: a meta-analysis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2021;1486:90.

Vaughan DA, Shah JS, Penzias AS, Domar AD, Toth TL. Infertility remains a top stressor despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:425–7.

Gupta M, Jaiswal P, Bansiwal R, Sethi A, Vanamail P, Kachhawa G, Kumari R, Mahey R. Anxieties and apprehensions among women waiting for fertility treatments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2021;152:441–3.

Qu P, Zhao D, Jia P, Dang S, Shi W, Wang M, Shi J. Changes in Mental Health of women undergoing assisted Reproductive Technology Treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in **’an, China. Front Public Health. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.645421.

Melo-Oliveira ME, Sá-Caputo D, Bachur JA, Paineiras-Domingos LL, Sonza A, Lacerda AC, Mendonça V, Seixas A, Taiar R, Bernardo-Filho M. Reported quality of life in countries with cases of COVID19: a systematic review. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2021;15:213–20.

Peivandi S, Razavi A, Shafiei S, Zamaniyan M, Orafaie A, Jafarpour H. (2020) Evaluation of attitude among infertile couples about continuing assisted reproductive technologies therapy during novel coronavirus outbreak. medRxiv 2020.09.01.20186320.

Rosielle K, Bergwerff J, Schreurs AMF, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on infertility patients and endometriosis patients in the Netherlands. Reprod Biomed Online. 2021;43:747–55.

Grens H, de Bruin JP, Huppelschoten A, Kremer JAM. Fertility workup with video consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic: pilot quantitative and qualitative study. JMIR Formative Research. 2022;6: e32000.

Acknowledgements

The protocol of the study was registered in PROSPERO (International prospective register of systematic reviews) under the code of CRD42023399725, Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023399725.

Funding

This study was funded by the Vice president for Research, at Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EI and AY performed the database search and study selection and prepared Fig. 1 and Additional File 1. EI and EMG performed the quality assessment of the studies and prepared Additional Files 2 and 3. EI and MM performed the data extraction from the studies and prepared Table 1, and Additional File 4. EI, RLR and AT performed analysis and interpretation of data for meta-analysis and prepared Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 and Tables 2, 3. RLR supervised the database search, study selection, quality assessment of the studies, and data extraction from the studies. EI and RLR wrote the main manuscript text. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Local Research Ethics Committee, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (Code of ethics: IR.MUMS.NURSE.REC.1401.056).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search Strategy for each database.

Additional file 2.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Additional file 3.

Quality assessment of the studies based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Additional file 4.

Data extraction table.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Iranifard, E., Yas, A., Mansouri Ghezelhesari, E. et al. Treatment suspension due to the coronavirus pandemic and mental health of infertile patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMC Public Health 24, 174 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17628-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17628-x