Abstract

Competencies ensure public health students and professionals have the necessary knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours to do their jobs effectively. Public health is a dynamic and complex field requiring robust competency statements and frameworks that are regularly renewed. Many countries have public health competencies, but there has been no evidence synthesis on how these are developed. Our research aim was to synthesize the extent and nature of the literature on approaches and best practices for competencies statement and framework development in the context of public health, including identifying the relevant literature on approaches for develo** competency statements and frameworks for public health students and professionals using a sco** review; and, synthesizing and describing approaches and best practices for develo** public health competency statements and frameworks using a thematic analysis of the literature identified by the sco** review. We conducted a sco** review and thematic analysis of the academic and grey literature to synthesize and describe approaches and best practices for develo** public health competency statements and frameworks. A systematic search of six databases uncovered 13 articles for inclusion. To scope the literature, articles were assessed for characteristics including study aim, design, methods, key results, gaps, and future research recommendations. Most included articles were peer-reviewed journal articles, used qualitative or mixed method design, and were focused on general, rather than specialist, public health practitioners. Thematic analysis resulted in the generation of six analytical themes that describe the multi-method approaches utilized in develo** competency statements and frameworks including literature reviews, expert consultation, and consensus-building. There was variability in the transparency of competency framework development, with challenges balancing foundational and discipline-specific competencies. Governance, and intersectoral and interdisciplinary competency, are needed to address complex public health issues. Understanding approaches and best practices for competency statement and framework development will support future evidence-informed iterations of public health competencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Competencies are defined as the knowledge, skills, values, and behaviours required to perform well within a profession and an organization [1]. Knowledge can be acquired through education and experience [1]. Skills result from the repeated application of knowledge, and behaviours reflect how individuals perform in various contexts [1]. Attitudes and values form the context in which competencies are practiced and are the beliefs that motivate people to act in different ways [2]. Competencies required for professional practice depend on many factors including an individual’s position within an organization and an organization’s needs [1, 3]. Within education, curriculum and pedagogical approaches provide students with opportunities to advance their knowledge and skills through didactic and experiential training [4, 5]. For both professional development and education, defining the competencies needed and creating development opportunities explicitly linked to them is essential.

There are various conceptualizations of competencies, including behavioural, performance continuum, and integrated or holistic approaches. Each conceptualization has strengths and weaknesses based on the complexity and interconnectedness of the approach, its focus on tasks or job performance, and how competencies are developed within individuals during their careers [6]. The holistic approach to competence conveys the interrelationship of knowledge, skills, behaviours, and attitudes/values [6, 7]. Frameworks and approaches to competencies are context-dependent and developmental, where there is progressive interaction between an individual’s tasks, abilities, and the systems and environments in which they perform [6]. Thus, establishing an integrated competency framework for any discipline or sector, including public health, provides clarity and professional standards, promotes reflective practice, and requires a clear understanding of the interconnectedness of the attributes required.

Competency statements for public health ensure students and practitioners have the necessary knowledge, skills, behaviours, and values to effectively perform [2, 8]. This promotes standardization in the field and provides a benchmark for capable personnel, allowing for a consistent approach to organizational planning and performance measurement, which in turn improves the quality of public health programs and services [5]. Competency frameworks define a set of competency statements and support their implementation through describing public health practice expectations and informing workforce planning and development [9]. There are a number of frameworks for public health competencies around the world, including the Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada [2], the United States (US) Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals [8], the WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region [10], the Public Health Competencies and Impact Variables for Low- and Middle-Income Countries [11], the Asia-Pacific Academic Consortium for Public Health Competency Framework [12], and the Core Competencies for Public Health: A Regional Framework for the Americas [13].Although each framework consists of different conceptualizations of competencies for different countries and sociopolitical regions, they are all based on a need for a tool that facilitates development of a knowledgeable and skilled public health workforce able to effectively address complex public health challenges [4].

Current public health challenges include multiple crises including climate change [14], mental health [15], and opioid use disorder [16], which overlap many sectors and disciplines. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing global health issues including health inequities, mental health, social isolation, and addictions [17, 18]. Additionally, declining trust in public health resulted from ineffective crisis communication and management [19], and a complex information ecosystem where mis/disinformation is widely circulating [20]. More than ever, public health needs competency frameworks that reflect the current multifaceted and overlap** public health challenges to ensure the workforce is adequately equipped to address them.

Core competency frameworks in public health are usually developed through collaboration with a range of public health experts and professionals. Public health competency frameworks are developed at various levels including the country level, organizational level, and discipline-specific public health practice to support workforce development planning, professional development, and improved public health action. For example, within Canada, the Core Competencies for Public Health were released in 2008 by the Public Health Agency of Canada in collaboration and consultation with public health practitioners, government, and experts [2]. Similarly in the US, the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals are developed and updated through extensive consultation and revision with the public health and population health sectors across the country [21]. This work also occurs on an organizational level within academia to develop programs and curriculum matched to public health competency frameworks [22], as well as for specific disciplines within public health such as implementation science [5], public health preparedness and response [23], and environmental public health [24].

The field of public health is dynamic and complex; thus, competency frameworks must be regularly updated to remain relevant. Approaches for develo** public health competency statements and frameworks must be optimized and mobilized to ensure they are relevant and have impact within public health [25]. Renewal of public health competency frameworks varies globally, with some countries regularly updating their competencies, such as the US (considers renewal three years after the prior release), while others, such as Canada, do not currently have a systematic approach to updating competencies, though there are calls for renewal and efforts are underway to revisit this. Identifying and describing approaches for the development of public health competency statements and frameworks will support future evidence-informed iterations, but no previous evidence synthesis has been conducted.

To address this gap, our goal is to synthesize the extent and nature of the literature on approaches and best practices for public health competencies statement and framework development. The objectives are:

-

1.

Identify relevant literature on approaches for develo** competency statements and frameworks for public health students and professionals using a sco** review; and,

-

2.

Synthesize and describe approaches and best practices for develo** public health competency statements and frameworks using a thematic analysis of the literature identified in the sco** review.

Methods

Review approach and team

The sco** review methods were based on the framework outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [26] and updated by Levac et al. [27]. A research team with expertise in the subject matter and methods was established to develop and guide the sco** review protocol and thematic analysis [26, 27]. A specialist research librarian with expertise in public health and research synthesis was consulted for the sco** review protocol. This sco** review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement for sco** reviews [28].

Review scope

Articles were included if they were published in English. There were no geographic or date restrictions. Peer-reviewed journal articles with qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed methods study designs, dissertations, and grey literature were included. Literature was included when it focused on develo** competency statements and frameworks for public health students and practitioners. Competency development in other disciplines (e.g., medicine, dentistry, etc.) was excluded unless it was explicitly public health focused (e.g., public health nursing).

Search strategy

In collaboration with the research team and a specialist research librarian, the search strategy was developed by exploring the relevant literature for keywords and controlled vocabulary. Originally, our review intended to focus on communication-related competencies for public health specifically, so controlled vocabulary and keywords were included to reflect this focus. During the screening process, it became apparent there was not enough literature focused on public health communication. The search strategy was expanded to focus across all competencies relevant to public health, including communication.

The search strategy was tested in Ovid via MEDLINE and refined to ensure the results were relevant to the review scope. The search strategy was then translated for use in other databases by modifying syntax, as needed. The final search was carried out on November 24, 2022, in the following databases: Ovid via MEDLINE (Table 1), PsycINFO, Web of Science, Communication and Mass Media Complete, ERIC, and CAB Direct. These databases were selected to provide a comprehensive coverage of public health, education, and communication sources.

To supplement the database search, we hand-searched the following journals: Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, American Journal of Public Health, Journal of Health Communication, Health Promotion Practice, and Health Communication. The journals were identified by examining the most frequently cited journals in the database search results. Additional peer-reviewed articles were also identified during the grey literature search. Grey literature was searched using Google through appropriate combinations of concepts (e.g., “core competencies” AND “public health”) and pages 1–10 were screened for relevant results.

Relevance screening

The results of the search were imported into DistillerSR review software [29] to facilitate screening by independent reviewers and track all steps. Deduplication of results occurred in DistillerSR after all relevant citations were imported from Mendeley [30]. Title and abstract, and full-text screening were also conducted in DistillerSR. Reviewers (MM and CF) pilot tested ten random articles to ensure understanding of the inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers (MM and CF) screened the title and abstract of each article using a screening form and any conflicts were resolved through discussion. Kappa was 0.81 for title and abstract screening, indicating high agreement [31].

The full text of articles deemed potentially relevant during the title and abstract screening were obtained and screened independently by the same two reviewers. Steps were taken to obtain the full text of all articles including searching within the University of Guelph Library, using Google and Google Scholar, and contacting the author directly through ResearchGate or their publicly available institutional email. A screening form was developed in collaboration with the research team and pre-tested before implementation. The form assessed each article’s eligibility for inclusion in the review by the following criteria: literature type, language, population, and measurement, evaluation, or detailed report of competency statement or framework development in public health students and/or the workforce. After completion of full-text screening, Kappa was 0.80, indicating high agreement [31]. Conflicts were resolved through discussion to the point of reaching agreement for inclusion or exclusion in the review.

Data extraction

Two researchers conducted data extraction for the included articles (MM and CF). Each researcher acted as the primary data extractor for half of the dataset and validated the other half as the secondary data extractor. Key information was extracted using an Excel form developed in collaboration with the research team [32]. The following information was extracted from each included article: title, author(s), year, article type, country of origin, study design, study aim, methods, theories or frameworks included, institutions involved in develo** competency statements, existing competency frameworks included, focus of competency framework (e.g., general or discipline-specific), process used to develop competency statements or framework, level of competency development focus (e.g., nation-wide, organizational, etc.), target population (e.g., graduate student, general public health practitioner), transparency of the process, lessons learned, implementing and adoption of competency statements or framework, evaluation of the process, bias identified, and future research directions.

The results of the data extraction were thematically analyzed following the method outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [26] and updated by Levac et al. [27]. First, the research team developed key areas to capture results for data extraction to answer objective 2, including transparency of methods and results, evaluation of the process, lessons learned, and implementation/adoption of the competencies. One researcher (MM) coded the extracted data line-by-line, as well as revisited the full text articles, to develop an initial thematic framework that described approaches and best practices for develo** competency frameworks in public health. Codes were inductively created based on the key areas of data extraction outlined above and refined into larger concepts where data overlapped to generate initial themes. Significant outliers were captured in the coding and incorporated into themes where appropriate. Approaches for develo** competency statements and frameworks described any methods undertaken and/or key recommendations for generating competency statements for public health that outline the values, knowledge, skills, and behaviours needed to effectively perform in various public health roles. Best practices describe areas of significant overlap in the data that reported successful methods or recommendations for develo**, implementing, and/or evaluating competency statements and frameworks for public health. The research team collaboratively discussed and refined the themes to provide perspective and triangulation of results, ultimately develo** six analytical themes. The research team also identified any areas of ambiguity during discussion and/or revisions and MM revisited the extracted and coded data, as well as full text articles, to add detail. The research team then collaboratively discussed, refined, and finalized the analytical thematic framework.

Results

Search and selection of articles

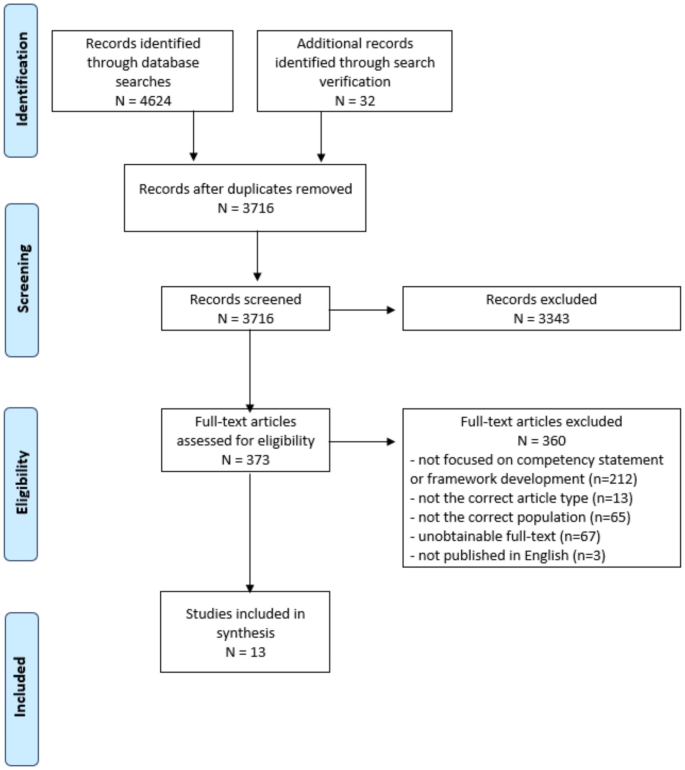

A total of 3,716 articles were screened at the title and abstract stage following deduplication. Next, 373 full-text articles were reviewed for relevance, with 13 studies identified for inclusion. Figure 1 depicts the PRISMA flow diagram of the article screening and inclusion process.

Characterization of Articles included

Most included articles were peer-reviewed journal articles, used qualitative or mixed method design, and were targeted towards generalist public health practitioners (Table 2). See Supplementary Table 1 for the data extraction results.

Thematic analysis

Six themes were generated to describe the approaches and best practices for develo** competency statements and frameworks for public health. The themes related to the approaches include initial methods used, building consensus, and transparency in reporting. Themes related to best practices include governance and coordination and a multifaceted approach for addressing complex public health challenges. The theme describing develo** foundational and discipline-specific competencies and those that apply to varying levels of expertise included approaches and best practices.

Initial competency statements are developed using literature reviews and expert consultations

Literature reviews [33,34,35,36,37], expert consultation [38,39,40,41], or a combination of both [35, 36, 42, 35], and for health literacy for public health professionals [34]. Grey literature, including existing country-level public health competencies (e.g., USA, Europe, Canada, New Zealand, Spain), existing competency frameworks (e.g., Emergency Preparedness Core Competencies for Public Health Workers), textbooks, and public health education curricula was frequently included in literature reviews for competency list development [33, 35, 37, 39, 37], public health epidemiology [44], and for senior public health officials [39]. Additional methods for getting started included conducting an environmental scan, which was used to develop Indigenous public health core competencies [36].

As a second step, expert consultations took place using interviews and surveys to gather information relevant to competency framework development, including feedback on competency statements, contextual factors, and responsibilities of and gaps in the workforce, including at various levels of public health practice [42, 35]. Exemplar practitioners who demonstrate the competencies within well-established practices can model the knowledge, skills, and abilities required within a particular context [40, 41]; however, expert consultations are not an appropriate first step when the area of practice is emerging and there is no history of exemplar practitioners [34, 40]. Representation is important for expert consultations: Indigenous peoples’ leadership in creating an Indigenous competency framework ensured their beliefs, values, and knowledge were central [36]. Context, including culture, geography, experience, and education must be considered when identifying evidence and theory for competency list development [37].

While some of the included literature identified potential challenges in gathering and synthesizing diverse expert opinions within their methods [34, 36, 39, 41], no insights on how these were addressed during the research were shared in the results or discussion. One exception was that participants of a consensus-building process with less expertise had some difficulty understanding more complex competencies [41]. The authors did not elaborate on how this may have impacted the results or how they addressed this issue during the research, other than recommending that further research in this area is needed.

Public health competency statement development is consensus-driven with practitioners and researchers

Expert consultation and validation by experts and practitioners must be included to increase the impact of competency frameworks [34, 40,41,42,34].

Purposive sampling of experts to gather various levels of experience and expertise within various public health disciplines was frequently used [34, 37, 41,42,35, 37, 40, 42] of competencies. Likert scales were used, including a 4-point scale of importance ranging from 1 (very important) to 4 (not important) [34], a 5-point scale of importance ranging from 0 (not used at all) to 4 (essential) [42], and a 5-point agreement scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) [44]. Competency statement acceptance, rejection, or clarification based on feedback through surveys were sometimes reported [34, 44].

Transparency of consensus-building processes for develo** competency frameworks varied

Reporting transparency regarding how consensus on competency frameworks was reached varied. Some studies were very detailed [34, 39, 41, 42] while others less so [35, 38, 45].

Studies often reported response rates and agreement for all competency items included [34, 35, 39, 44]. Statistical analysis, usually as associations between agreement ratings, and agreement levels for included competency statements, were also reported [39, 42,46], making it more difficult to assess agreement or importance during consensus-building [34, 44].

Foundational competencies to address systemic factors related to colonialism and incorporate non-Western knowledge and Indigenous governance structures in public health are also necessary [36]. For example, community health workers are excluded from needing to have all the core competencies in the Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada 1.0 release [36]. However, these public health practitioners play a central role in Indigenous health and lack of proficiency in all the competencies can significantly impact Ingenious health [36].

Discipline-specific competencies define the roles within public health and guide professional development and education within the specialty [39,40,41,42,38] and the work is not duplicated [40]. Various formats for competency frameworks were used, including Tables (33,34,39,42,43), lists [35, 37, 38, 41], visual models [36, 39, 40]. New and revitalized frameworks should be mapped against job descriptions in public health to identify gaps [39]. Practitioners were apprehensive around competency frameworks being used for accreditation and performance evaluation [44]. Training programs should be designed and assessed to ensure they are able to develop the competencies that are outlined within frameworks [39,40,41,42]. Professional development for the current public health workforce must be integrated within the development and implementation of public health competency frameworks [34, 39, 41, 42, 44, 45].

Values underpin and support competency frameworks to enable public health to address complex public health challenges

Values should be reflected in competency statements, although these are the most difficult to develop and measure [36, 38, 35, 36, 38, 42].

Although many frameworks highlight the importance of reducing health inequities (e.g., in the preamble), they varied in terms of the emphasis placed within competency statements on reducing health inequities and culturally appropriate approaches to public health [36, 39]. Competencies for providing culturally appropriate public health and healthcare for Indigenous peoples are vital and can contribute to overcoming misunderstanding, discrimination, and racism [36]. The explicit recognition of Indigenous peoples, colonialism and the impact on health, and related health inequities throughout the public health core competencies, including integration within definitions in the glossary and practice examples, is necessary [36].

Public health competencies are necessary to facilitate shared understanding of expectations and actions required to address complex public health issues that are intersectoral and interdisciplinary [38, 41, 45]. The ability to influence policy and develop partnerships can be negatively influenced by predominant culture and requires political will and in some cases governmental reform to ensure competencies to address complex public health issues are included in public health frameworks and practice [36, 38, 41, 3). In Table 3, the content within the Actions to Achieve Recommendation column summarizes key aspects of the results and discussion that relate to the success and impact of the approaches and best practices for develo** competency statements and frameworks identified. We compare and contrast our findings to similar literature in veterinary medicine and healthcare to put the recommendations into a wider context and body of knowledge.

A strong evidence-informed foundation for develo** competency statements bridges the research-practice interface. The quality of the evidence used to generate findings is key to the reliability and validity of the resulting competency frameworks [47, 48]. Literature reviews, expert consultations, review of existing competency frameworks, and environmental scans can be used as a first step to gather evidence [48, 49] that can close the gap between research and practical knowledge and provides contextual evidence about the public health system in Canada. Within healthcare, a similar process is used where literature reviews [50], surveys [51], and interviews [52] were used to develop the initial list of competency statements for further consensus-building [49]. This approach is consistent with the steps outlined in the Delphi and modified Delphi techniques [48, 49].

Multi-step processes for consensus-building, including expert consultation and iterative methods, increase the validity of results through the incorporation expert knowledge and research findings [49]. Expert consultation is a key step in the consensus-building process to ensure a strong basis in the evidence [47, 48]. Practitioners and researchers are most often included in consensus-building processes in the included public health literature and within healthcare [50,51,52] and veterinary medicine [53, 54]. Consensus-building processes to develop competency frameworks in the included literature were most often academia-led and conducted via expert consultations, surveys, and modified Delphi technique with public health academics and practitioners. However, public health goes beyond the public health sector and the consensus-building process should include community-based organizations, government, and other stakeholders to ensure community needs and values are being met [45]. The inclusion of other actors ensures competencies are reflective of collaborative, intersectoral, community-based public action.

Transparent and comprehensive reporting of the methods and results of consensus-building processes for public health competencies and frameworks is needed so that the research can be repeated, or similar processes can be implemented, and understood. The details of the consensus-building process were lacking in some studies – a similar trend has found for competency framework development in the healthcare [50,51,52] and veterinary medicine [53, 54]. This is also true across health research in general where lack of transparent reporting makes interpreting the methods, evaluating the reliability and validity of results, and comparing to the wider body of knowledge difficult [55]. Research with low transparency has implications for use including possible harms and unintended consequences and reducing the possibility of benefits, contributing to lower overall public health impact [56]. Competency theory and validated instruments that guide consensus-building and ensure reliable and accurate results were identified as lacking by included studies. A threshold for agreement has also not been validated, making it difficult for studies to select an a priori level of agreement [34, 39]. The focus on validated instruments within competency framework research tends to be for measuring perceived competence development in education [57] or professional development [58] rather than the process itself of develo** consensus when building competency frameworks. Pilot testing of instruments for measuring agreement during consensus-building can help to ensure validity before the process begins. The CONFRED-HP (COmpeteNcy FramEwork Development in health professions) recommendations for reporting provides researchers with clear descriptions of vital areas for reporting the development of competency frameworks to increase the transparency and trustworthiness of the research and allow for informed decision-making around its use [59]. The EQUATOR (Enhancing the Quality and Transparency Of health Research) Network guidelines can be used for increasing the transparency and trustworthiness of research on building competencies in public health students and practitioners [55]. Reporting guidelines are important tools that support best practices in research reporting, contributing to increased transparency and research impact [56].

Public health effectiveness relies on how practitioners combine their individual values, knowledge, skills, and behaviours to address community needs. The effectiveness of a public health team and workforce results from this combination across individuals, levels, and disciplines [60], although interdisciplinary teamwork is difficult [61]. Foundational competencies lay the groundwork for a common understanding of what is required to do good work in public health. Discipline-specific competencies allow for public health practitioners to have opportunities to learn and build on foundational competencies for additional mastery [62]. Despite this, diversity of competency frameworks and levels of competencies (expert and foundational vs. specialized) are key challenges in develo** competency frameworks [63]. The diversity in competencies and the subsequent difficulties have implications for workforce planning and development and education [63]. Frameworks that combine different ways of knowing, including theory and practice-based knowledge, and practical examples can help contextualize the competencies [63] to different expertise levels and specializations within public health. Competencies related to communication and interdisciplinarity can assist with the challenges of multiple levels of expertise and foundational and discipline-specific competencies as well [25, 60, 64].

Integrating competency frameworks into practice requires governance and coordinated efforts, as identified by the included literature. Governance of public health core competencies is necessary to ensure competency frameworks are up-to-date, appropriately resourced, and reflective of current public health needs and values. Within a governance structure, funding, standards and quality assurance, and a comprehensive framework rollout plan were also identified as necessary. A lack of resources and infrastructure to support the development, implementation, evaluation, and ongoing refresh of competencies are key contextual factors influencing the success of competency frameworks [46]. This complements findings from another review indicating that a comprehensive and coordinated implementation strategy, including resources, governance, and collaboration, is associated with the use and impact of competency frameworks [25].

Design and readability of competency frameworks impacts their use and effectiveness. Competency statements should be written in clear language and be reasonable in number, and frameworks should be user-friendly, use tables, and be translated where applicable [25, 65,66,67]. Although there were a range of presentations in the included literature, most did not evaluate the usefulness of the design, with the exception of Shickle et al. [41], which found clear language was preferred.

Finally, a multifaceted approach to develo** and measuring competencies is needed to address complex public health challenges. Complex public health issues including climate change, global health, health inequities, and racism/discrimination must be addressed, reflected, and integrated into public health competencies. Values that guide our research, practice, and community interactions must also be reflected in competency statements and frameworks to address these complex issues. Values are most often geared at individual practitioners but should also be extended to organizational values, as these create a culture and context for individual values to guide practice [68]. In the context of Indigenous health and reconciliation, it is imperative to explicitly integrate decolonization, anti-racist, and culturally appropriate public health practice into the public health competencies [36]. Within other disciplines, including midwifery [69] and healthcare [70], core competencies have been proposed to guide providers working to address health disparities and ensure culturally safe and effective services for Indigenous Peoples. Structural factors, including power dynamics, current and historical relationships, and needs and resources of marginalized groups must be incorporated into competency frameworks and directly influence use [25, 46]. Competency frameworks should be flexible enough to serve as practice guidelines that can be adapted to suit the specific context, complexity, and population requirements in which it is being applied [25].

Limitations

Within the current study, the results could be limited by the selection of databases; however, we used a number of diverse databases and supplemented the search by hand searching and grey literature. Further, our research intended to focus on health communication, but found the literature to be greatly lacking, rendering a more focused review impossible. The inclusion of health communication as a key concept within the search strategy may have limited the results to those public health competency frameworks that included communication. Communication is identified across many disciplines, including public health, as a key competency, so this aspect may not have had a great impact on the results. The results may also be limited by language bias as studies were only included if they were published in English. Although we had no date or geographic restrictions, this language bias may have limited articles globally, especially those that are low or low-middle income countries, impacting the overall generalizability of results.

Biases created by study design of the included articles also result in limitations, including participant recruitment and the methods used to understand their perspectives. Information bias was present as most studies employ purposive sampling to select consensus-building groups [34, 35, 37, 41, 44]. There is also no established target number of participants for consensus-building processes for develo** competency frameworks (Coleman et al., 2013) and sample sizes can be small [35, 41, 42]. The nature of participant experience and breadth of perspective could also be limited by the sampling [34, 37, 39, 41, 42, 44]. Further, many studies relied on expert knowledge and the literature to develop competency frameworks, but many areas of public health are rapidly expanding and changing [34] and/or lack the theoretical underpinning necessary to ensure reliable and valid results [34, 39, 41]. Some studies reported an a priori cut-off point for agreement [34, 39]; however, this threshold is not validated in the research [34, 39].

Future research directions

Research is needed to distinguish between competencies required for core public health roles versus those for specialized roles. Research specific to the various disciplines, including public health communication, is needed to determine best practices for develo**, implementing, and evaluating competency frameworks. Research reporting on the implementation and evaluation of foundational and discipline-specific competency frameworks is needed to help understand best practices and challenges in harmonizing varying competency frameworks in practice. The creation and implementation, reliability, and validity of a competency assessment instrument should also be explored. Some areas of literature related to competency statements and frameworks, such as health literacy, are heavily skewed towards healthcare and medicine, and more work is needed centring different topics within public health so that the focus is at the population level rather than the patient/individual level. Research to strengthen the connection between competency frameworks and the learning outcomes of public health graduate training and professional development would be valuable. Finally, research is needed to evaluate consensus-building processes from the perspective of participants and the utility and impact of the final framework, including design considerations. Literature in this area is largely focused on competency framework development and not on the evaluation of the process of development, implementation, use, or impact of the frameworks in practice.

Conclusion

The review scopes and analyzes the literature on develo** competency statements and frameworks for public health. The findings highlight the similarities in approaches for develo** competency statements and frameworks across studies, including using a multi-step process that involves literature reviews, expert consultations, and consensus-building. Foundational and discipline-specific competency frameworks, as well those that are role- and expertise-specific, including for students, new practitioners, and leaders, are needed. Variation in transparency of reporting the process of develo** competency statements and frameworks exists, with some studies including very detailed methods and results while others only high-level overviews. High transparency and multi-step processes are necessary to ensure the validity, reliability, and utility of competency statements and frameworks. Governance and comprehensive plans for implementation and renewal are necessary to ensure integration of competencies into professional standards and professional development. Values that reflect culture and social justice when addressing complex public health needs must be integrated into public health competency statements and frameworks.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

National Institutes of Health. Office of Human Resources. 2017 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. What are competencies? Available from: https://hr.nih.gov/about/faq/working-nih/competencies/what-are-competencies.

Public Health Agency of Canada. Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada. Government of Canada [Internet]. Government of Canada. 2008. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/public-health-practice/skills-online/core-competencies-public-health-canada/cc-manual-eng090407.pdf.

Public Health Association of BC. Public Health Core Competency Development [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://phabc.org/public-health-core-competency-development/.

Hunter MB, Ogunlayi F, Middleton J, Squires N. Strengthening capacity through competency-based education and training to deliver the essential public health functions: reflection on roadmap to build public health workforce. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(3):e011310.

Schultes MT, Aijaz M, Klug J, Fixsen DL. Competences for implementation science: what trainees need to learn and where they learn it. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(1):19–35.

Belita E. Development and Psychometric Assessment of the Evidence-Informed Decision-Making Competence Measure for Public Health Nursing [Internet]. [Hamilton, Ontario, Canada]: McMaster University; 2020. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11375/25765.

Cheetham G, Chivers G. The reflective (and competent) practitioner: a model of professional competence which seeks to harmonise the reflective practitioner and competence-based approaches. J Eur Industrial Train. 1998;22(7):267–76.

Public Health Foundation. PHF. 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals: Domains. Available from: https://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/Core_Competencies_Domains.aspx.

Batt A, Williams B, Rich J, Tavares W. A Six-Step Model for Develo** Competency Frameworks in the Healthcare Professions. Frontiers in Medicine [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 May 4];8. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.789828.

World Health Organization. WHO-ASPHER Competency Framework for the Public Health Workforce in the European Region [Internet], Copenhagen. Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Available from: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/444576/WHO-ASPHER-Public-Health-Workforce-Europe-eng.pdf.

Zwanikken PA, Alexander L, Huong NT, Qian X, Valladares LM, Mohamed NA, et al. Validation of public health competencies and impact variables for low- and middle-income countries. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):55.

Karunathilake IM, Liyanage CK. Accreditation of Public Health Education in the Asia-Pacific Region. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(1):38–44.

Pan American Health Organization. Pan American Health Organization. 2013 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. Core Competencies for Public Health: A Regional Framework for the Americas - PAHO/WHO. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/core-competencies-public-health-regional-framework-americas.

World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. Climate change. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health.

Kuehn BM. WHO: Pandemic sparked a push for global Mental Health Transformation. JAMA. 2022;328(1):5–7.

Americas TLRH. Opioid crisis: addiction, overprescription, and insufficient primary prevention. The Lancet Regional Health – Americas [Internet]. 2023 Jul 1 [cited 2023 Oct 23];23. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(23)00131-X/fulltext.

Canada PHA. of. aem. 2020 [cited 2020 Nov 3]. From risk to resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19 – The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html?utm_source=Canadian+Public+Health+Assocation&utm_campaign=cedbc06deb-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_10_30_02_02&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_1f88f45ba0-cedbc06deb-181652396.

Health TLP. COVID-19 pandemic: what’s next for public health? The Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(5):e391.

Leslie J, Council on Foreign Relations. 2023 [cited 2023 Oct 23]. The Crisis of Trust in Public Health | Think Global Health. Available from: https://www.thinkglobalhealth.org/article/crisis-trust-public-health.

Illari L, Restrepo NJ, Johnson NF. Rise of post-pandemic resilience across the distrust ecosystem. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):15640.

Public Health Foundation. PHF. 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. 2021 Revision of the Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals. Available from: http://www.phf.org/programs/corecompetencies/Pages/2021_Revision_of_the_Core_Competencies_for_Public_Health_Professionals.aspx.

Calhoun JG, Ramiah K, Weist EM, Shortell SM. Development of a core competency model for the Master of Public Health Degree. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(9):1598–607.

Ablah E, Elizabeth McGean Weist MA, John E, McElligott MPH, Laura A, Biesiadecki M, Audrey R, Gotsch D, William Keck C. Public health preparedness and response competency model methodology. Am J Disaster Med. 2013;8(1):49–56.

Wallar LE, McEwen SA, Sargeant JM, Mercer NJ, Papadopoulos A. Prioritizing professional competencies in environmental public health: a best–worst scaling experiment. Environ Health Rev. 2018;61(2):50–63.

Lebrun-Pare F, Malai D, Gervais MJ. Advisory on the Use of Competency Frameworks in Public Health: Literature Review, Exploratory Interviews and Courses of Action [Internet]. Quebec: INSPQ Center for Expertise and Reference in Public Health; 2021. Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/publications/2827.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Sco** studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Sco** studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for sco** reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

DistillerSR [Internet], Ottawa C. 2023. Available from: https://www.distillersr.com/.

Mendeley. Mendeley Reference Manager [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://www.mendeley.com/reference-management/reference-manager.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–82.

Microsoft Corporation. Microsoft Excel [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://office.microsoft.com/excel.

Baseman JG, Marsden-Haug N, Holt VL, Stergachis A, Goldoft M, Gale JL. Epidemiology Competency Development and Application To Training for Local and Regional Public Health Practitioners. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(1suppl):44–52.

Coleman CA, Hudson S, Maine LL. Health Literacy Practices and Educational Competencies for Health professionals: a Consensus Study. J Health Communication. 2013;18(sup1):82–102.

Hagopian A, Spigner C, Gorstein JL, Mercer MA, Pfeiffer J, Frey S, et al. Develo** competencies for a Graduate School Curriculum in International Health. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(3):408–14.

Hunt S, Review of Core Competencies for Public Health. An Aboriginal Public Health Perspective [Internet]. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal health; 2015. Available from: https://www.nccih.ca/docs/context/RPT-CoreCompentenciesHealth-Hunt-EN.pdf.

Olson D, Hoeppner M, Larson S, Ehrenberg A, Leitheiser AT. Lifelong Learning for Public Health Practice Education: a Model Curriculum for Bioterrorism and Emergency Readiness. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(2suppl):53–64.

Allegrante JP, Barry MM, Airhihenbuwa CO, Auld ME, Collins JL, Lamarre MC et al. Domains of Core Competency, Standards, and Quality Assurance for Building Global Capacity in Health Promotion: The Galway Consensus Conference Statement. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):476–82.

Bhandari S, Wahl B, Bennett S, Engineer CY, Pandey P, Peters DH. Identifying core competencies for practicing public health professionals: results from a Delphi exercise in Uttar Pradesh, India. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1737.

Gebbie KM. Competency-To-Curriculm Toolkit [Internet]. Columbia University School of Nursing and Association for Prevention Teaching and Research; 2008 Mar. Available from: https://www.phf.org/resourcestools/Documents/Competency_to_Curriculum_Toolkit08.pdf.

Shickle D, Stroud L, Day M, Smith K. The applicability of the UK Public Health Skills and Knowledge Framework to the practitioner workforce: lessons for competency framework development. J Public Health. 2019;41(1):e109–17.

Park SY, Harrington NG, Crosswell LH, Parvanta C. Competencies for Health communication specialists: Survey of Health communication educators and practitioners. J Health Communication. 2021;1–21.

Shi L, Fan L, **ao H, Chen Z, Tong X, Liu M, et al. Constructing a general competency model for Chinese public health physicians: a qualitative and quantitative study. Eur J Pub Health. 2019;29(6):1184–91.

Bondy SJ, Johnson I, Cole DC, Bercovitz K. Identifying Core Competencies for Public Health Epidemiologists. Can J Public Health. 2008;99(4):246–51.

Wright J, Rao M, Walker K. The UK Public Health Skills and Career Framework—could it help to make public health the business of every workforce? Public Health. 2008;122(6):541–4.

Battel-Kirk B, Barry MM. Has the Development of Health Promotion Competencies Made a difference? A sco** review of the literature. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(5):824–42.

Barrett D, Heale R. What are Delphi studies? Evid Based Nurs. 2020;23(3):68–9.

Staykova MPS. Rediscovering the Delphi Technique: A Review of the Literature. 2019 Jan 31 [cited 2023 Mar 28];6(1). Available from: http://scholarpublishing.org/index.php/ASSRJ/article/view/5959.

Arifin MA. Applying modified e-Delphi technique: Guideline for HR researchers and practitioners for develo** competency profiles during Covid-19 pandemic. IJARBSS. 2021;11(9):Pages746–754.

Mitsuyama T, Son D, Eto M, Kikukawa M. Competency lists for urban general practitioners/family physicians using the modified Delphi method. BMC Prim Care. 2023;24(1):21.

Taylor RM, Feltbower RG, Aslam N, Raine R, Whelan JS, Gibson F. Modified international e-Delphi survey to define healthcare professional competencies for working with teenagers and young adults with cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e011361.

Janke KK, Kelley KA, Sweet BV, Kuba SE. A modified Delphi process to define competencies for Assessment leads supporting a doctor of Pharmacy Program. AJPE. 2016;80(10):167.

Bell MA, Cake MA, King LT, Mansfield CF. Identifying the capabilities most important for veterinary employability using a modified Delphi process. Veterinary Record [Internet]. 2022 Apr [cited 2023 Mar 22];190(7). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1002/vetr.777.

Duijn CCMA, ten Cate O, Kremer WDJ, Bok HGJ. The development of Entrustable Professional activities for Competency-Based Veterinary Education in Farm Animal Health. J Vet Med Educ. 2019;46(2):218–24.

Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med. 2010;8(1):24.

Nicholls SG, Langan SM, Benchimol EI, Moher D. Reporting transparency: making the ethical mandate explicit. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):44.

Chan CKY, Luk LYY. Development and validation of an instrument measuring undergraduate students’ perceived holistic competencies. Assess Evaluation High Educ. 2021;46(3):467–82.

Miranda FBG, Mazzo A, Alves Pereira-Junior G. Construction and validation of competency frameworks for the training of nurses in emergencies. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet]. 2018 Oct 25 [cited 2023 Mar 22];26(0). Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-11692018000100368&lng=en&tlng=en.

Batt AM, Tavares W, Horsley T, Rich JV, Williams B, Collaborators CONFERD-HP, et al. CONFERD-HP: recommendations for reporting COmpeteNcy FramEwoRk Development in health professions. Br J Surg. 2023;110(2):233–41.

Kozlowski SWJ, Ilgen DR. Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2006;7(3):77–124.

Zumstein-Shaha M, Grace PJ. Competency frameworks, nursing perspectives, and interdisciplinary collaborations for good patient care: delineating boundaries. Nurs Philos. 2023;24(1):e12402.

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health. Do public health discipline-specific competencies provide guidance for equity-focused practice? [Internet]. Antigonish, NS: St Francis Xavier University. 2015. Available from: https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/do-public-health-discipline-specific-competencies-provide-guidance-for-equi.

Coombe L, Severinsen CA, Robinson P. Map** competency frameworks: implications for public health curricula design. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2022;46(5):564–71.

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework [Internet]. University of British Columbia. 2010 Feb. Available from: https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf.

Burnett E, Curran E, Loveday H, Kiernan M, Tannahill M. The outcome competency framework for practitioners in Infection prevention and control: use of the outcome logic model for evaluation. J Infect Prev. 2014;15(1):14–21.

Cotter C. Review of the Public Health Skills and Knowledge Framework (PHSKF) Report on a series of consultations [Internet]. London, England: Public Health England; 2015. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/449309/PHSKF_Review_spring_2015.pdf.

Nash RE, Chalmers L, Stupans I, Brown N. Knowledge, use and perceived relevance of a profession’s competency standards; implications for Pharmacy Education. Int J Pharm Pract. 2016;24(6):390–402.

Standford N. Designing competency frameworks [Internet]. Naomi Stanford. 2020 [cited 2023 May 5]. Available from: https://naomistanford.com/2020/06/30/designing-competency-frameworks/.

Lavallee B, Neville A, Anderson M, Shore B, Diffey L, First Nations, Inuit. Métis Health CORE COMPETENCIES [Internet]. Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada and the Association of Faculties of Medicine Canada; 2009 Apr. Available from: www.ipac-amic.org; www.afmc.ca/social-aboriginal-health-e.php.

Baba L. Cultural Safety in Frist Nations, Inuit and Metis Public Health. Price George, BC: National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health; 2013.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) in the form of a CIHR Catalyst Grant (FRN 184647).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M., J.E.M., L.E.G., and A.P.; methodology, M.M., J.E.M.,; formal analysis, M.M., J.E.M, and C.F.; investigation, M.M., C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M., C.F., L.E.G., J.E.M., and A.P.; supervision J.E.M.; validation; M.M. and J.E.M.; visualization; M.M.; project administration, J.E.M.; funding acquisition, J.E.M., M.M., L.E.G., and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

MacKay, M., Ford, C., Grant, L.E. et al. Develo** public health competency statements and frameworks: a sco** review and thematic analysis of approaches. BMC Public Health 23, 2240 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17182-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17182-6