Abstract

Background

A considerable number of individuals infected with COVID-19 experience residual symptoms after the acute phase. However, the correlation between residual symptoms and psychological distress and underlying mechanisms are scarcely studied. We aim to explore the association between residual symptoms of COVID-19 and psychological distress, specifically depression, anxiety, and fear of COVID-19, and examine the role of risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty in the association.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted by online questionnaire-based approach in mid-January 2023. Self-reported demographic characteristics, COVID-19-related information, and residual symptoms were collected. Depression, anxiety, fear, risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty were evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), COVID-19 Risk Perception Scale and Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 (IUS-12), respectively. Linear regression analyses were conducted to explore the associations. A moderated mediation model was then constructed to examine the role of risk perception of COVID-19 and intolerance of uncertainty in the association between residual symptoms and psychological distress.

Results

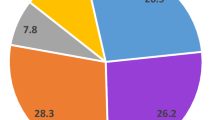

1735 participants effectively completed the survey. 34.9% of the patients experienced residual symptoms after acute phase of COVID-19. Psychological distress was markedly increased by COVID-19 infection, while residual symptoms had a significant impact on psychological distress (Ps < 0.001), including depression (β = 0.23), anxiety (β = 0.21), and fear of COVID-19 (β = 0.14). Risk perception served as a mediator between residual symptoms and all forms of psychological distress, while intolerance of uncertainty moderated the effect of risk perception on depression and anxiety.

Conclusion

A considerable proportion of patients experience residual symptoms after acute phase of COVID-19, which have a significant impact on psychological distress. Risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty play a moderated-mediation role in the association between residual symptoms and depression/anxiety. It highly suggests that effective treatment for residual symptoms, maintaining appropriate risk perception and improving intolerance of uncertainty are critical strategies to alleviate COVID-19 infection-associated psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The novel coronavirus pneumonia has spread globally since 2020 [1], resulting in almost 701 million infections and approximately 6.9 million deaths by early 2024 [2]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has significant detrimental effects on the global economy [3], physical health (severe acute syndrome [4] and sequelae [5]), as well as people’s daily lives [6, 7]. The waves of COVID-19 pandemic marked by the emergence of new variants and vaccination, e.g., the outbreak of the Omicron variant and Delta variant [17]. It indicates that psychological distress and associated factors may vary at different stages of the peri-infection period. Previous studies focus on the psychological distress either among general population or among patients with Long COVID-19 [5, 13,24].

Risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty (IU), two major factors involving in disease-associated psychological distress, may contribute to the effect of residual symptoms on psychological distress [25,26,27]. Risk perception of COVID-19 refers to an individual’s cognitive response, assessment, experience, and subjective feelings toward the risk associated with COVID-19 [28]. Residual symptoms following acute COVID-19 syndrome may indicate a prolonged negative impact on health [29], potentially leading to an increased perception of severity and persistence of COVID-19. The elevated levels of risk perception and appraisal may link to increased psychological distress [30]. Moreover, IU is a personal psychological trait that reflects a person’s inability to endure aversive responses, leading to negative reactions toward unpredictable situations or uncertain events, regardless of the probability of occurrence [31, 32]. For example, IU was a significant predictor of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic [33]. It suggests that IU may potentially influence the connection between risk perception and psychological distress.

This study aimed to examine the psychological distress of individuals during the COVID-19 infection process, from high risk to contact the virus to infected within 1 month. Moreover, the effect of residual symptoms on psychological distress was examined, which fills the research gap between acute phase of COVID-19 and Long COVID. Furthermore, the moderated mediating effect of risk perception and IU on the relationship between residual symptoms and psychological distress was explored. Three hypotheses were proposed to achieve these objectives: (1) The level of psychological distress varies among individuals at different stages of COVID-19 infection; (2) Individuals with residual symptoms are more likely to experience more severe psychological distress; (3) The relationship between residual symptoms and psychological distress is mediated by risk perception and moderated by IU.

Methods

Study design and recruitment

This was a cross-sectional, descriptive and correlational study. Participants were categorized into different stages based on COVID-19 infection status, ranging from never being infected to fully recovery. The survey was conducted from January 12 to January 21, 2023. Most patients have recovered from acute phase of COVID-19 infection within this time window [34].

Convenience sampling was utilized in this study due to the unique nature of emergencies. Online recruitment was conducted in the form of Quick Response (QR) code through electronic questionnaires powered by “Questionnaire Star” (https://www.wjx.cn/). Participants were recruited using social media: WeChat and WeChat Moments. All participants were presented with study-related information and asked about consent preferences. The Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Kangning Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University approved this study (Approval Code: YJ-2023-16-01) following the Helsinki Declaration.

Participants

A total of 1800 individuals completed the questionnaires. The questionnaires were individually checked by two investigators to eliminate those with extremely short filling times (less than 200s) or obvious random filling. Individuals who had been infected with COVID-19 for more than one month were excluded. 1735 completed questionnaires were included in the study. The exclusion rate was 3.61%.

Measurements

Demographic factors and COVID-19-related information

Demographic factors were collected, including age, gender, religiosity, family financial situation, and physical health. COVID-19-related information was collected, including COVID-19 vaccination status, medicines preparation, financial losses during the pandemic and after lifting the COVID-19 policy, infection of relatives and friends, individual’s infection status and time of infection, recovery status, and any residual symptoms experienced after acute remission and nucleic acid turned negative.

Proposed stages of COVID-19 infection

The whole COVID-19 infection process was categorized into three stages based on the individual’s infection status (Supplementary Figure S1). The infection status was determined by asking, “Have you ever been infected with COVID-19?”, with three possible responses: (1) never, and do not exhibit any symptoms related to the virus such as fever, sore throat, cough, etc.; (2) never, but display suspicious symptoms related to the virus; and (3) have been infected with COVID-19 confirmed by a nucleic acid or antigen test. Participants who answered (1), (2), and (3) were categorized as stage 1, 2, and 3 groups, respectively. For participants who answered (3), an additional question “When were you first infected with COVID-19?” was asked. The response options were (1) within 1 week, (2) from 1 week to 1 month, and (3) over 1 month. Participants with answer (1) and (2) were clustered into ‘acute phase’ (stage 3a) and ‘chronic phase’ (stage 3c) of stage 3, respectively (Supplementary Figure S1). Participants with answer (3) were excluded from the current study.

Residual symptoms

COVID-19 related symptoms during the acute remission (within 1 month) were defined as residual symptoms, which differentiate from Long COVID (over 1 month). Residual symptoms should satisfy three criteria: (1) Individuals have been diagnosed with COVID-19 by nucleic acid or antigen detection; (2) Individuals have recovered from the acute syndrome and nucleic acid or antigen detection is negative; (3) COVID-19-related symptoms are still present within one month of infection.

To measure residual symptoms among participants who answered “have been recovered from COVID-19 acute syndrome and nucleus acid or antigen tests were negative”, the item ‘Do you still have symptoms (i.e., fever, cough, sore throat, stuffy nose, and fatigue)?’ was asked. Participants who answered ‘yes’ were categorized into the group with residual symptoms.

Risk perception of COVID-19

The COVID-19 Risk Perception Scale, developed by Cui ** with insecurity and uncertainty during COVID-19 infection. Therefore, high IU may amplify the effect of risk perception on depressive and anxiety symptoms, contributing to psychological distress. In contrast, the effect of risk perception on depression and anxiety tended to be non-significant in the participants with low IU, which indicated that IU plays a key role in the emergence of psychological distress in COVID-19 survivors. Previous studies have also found that IU was directly associated with higher depression and anxiety [25, 26], which is consistent with our study. Therefore, intervention in risk perception and IU may alleviate psychological distress. For instance, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) might be helpful to affect one’s perceived risk and uncertainty [62].

Despite the moderated effects found in models of depression and anxiety, a distinct pattern emerged in the associations with fear of COVID-19. The mediating effect of risk perception appeared to play a major role in the association between residual symptoms and fear of COVID-19, while the moderating effect of IU was not evident. The positive association between risk perception and fear of COVID-19 aligns with previous findings [63, 64]. High risk perception and compromised health status have been reported to be robust contributors to heightened fear of COVID-19 [65]. A decline in physical health status may alter the perception of the COVID-19 risk, consequently contributing to higher levels of fear of the disease. Fear is typically an emotion directing towards a specific object, serving to motivate people to avoid potential danger. In contrast to the effects in depression and anxiety models, IU did not modulate the relationship between risk perception and fear of COVID-19. This disparity suggests that the fear of COVID-19 may directly stem from specific and definite negative consequences of COVID-19, such as residual symptoms and distressing experiences.

Compared with manifestations of COVID-19 in its presymptomatic and prodromal periods, the emergence of post-COVID syndrome has become a more prevalent public health concern in the current period. As some residual symptoms may be persisted and evolve into post-COVID syndrome, there is a critical transition phase between the acute phase and post-COVID syndrome. Individuals in this transition phase may be especially at risk of psychological distress, as they experience more severe physical symptoms than post-COVID syndrome and worry about the risk of transforming to post-COVID syndrome. Since the psychological distress has been identified as a risk factor of post-COVID syndrome [66, 67], our research sheds light on the potential mediator and moderator in the relationship between residual symptoms and psychological distress. As discussed above, these psychological factors (i.e., risk perception and IU) have been identified as potential targets for psychological intervention, offering the possibility to mitigate psychological distress and the risk of post-COVID syndrome. Therefore, this study holds significant implications for co** with this critical transition phase, thereby addressing a notable gap in the existing body of COVID-19 research.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the possible psychological differences from never infected with COVID-19 stage to the chronic phase of COVID-19, and to explore the effects of residual symptoms on psychological distress and underlying mechanism. Our study identifies the significant impact of residual symptoms on psychological distress and the key role of risk perception and uncertainty intolerance (IU). It indicated that two psychological structures can be intervened in. However, the present study has several limitations. First, the generalizability of the study’s findings may be constrained by the use of convenience sampling and the limited number of elderly participants. As such, caution is warranted when extending the conclusions beyond the sampled population. Second, the limited number of participants within a week after COVID-19 infection should be considered when interpreting the subgroup analysis results. Third, this study follows a cross-sectional design, which necessitates longitudinal cohort studies to confirm the causality and long-term dynamics of residual symptoms.

Conclusion

A considerable proportion of patients experience residual symptoms after the acute phase of COVID-19, which have a significant impact on psychological distress. Risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty play a moderated-mediation role in the association between residual symptoms and depression/anxiety. It highly suggests that effective treatment for residual symptoms, maintaining appropriate risk perception and improving intolerance of uncertainty are critical strategies to alleviate COVID-19 infection-associated psychological distress.

Data availability

All data used and/or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding authors upon request (Email: wuyili@wmu.edu.cn). They are not publicly available, in accordance with the Ethics Review Authority.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

The coronavirus disease 2019

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- GAD-7:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7

- FCV-19S:

-

Fear of COVID-19 Scale

- IU:

-

Intolerance of uncertainty

- IUS-12:

-

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12

- ANCOVAs:

-

Analyses of covariance

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

References

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Med Atenei Parm. 2020;91:157–60.

Worldometer. COVID - Coronavirus Statistics. 2024. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed 5 Jan 2024.

Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, Iosifidis C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): a review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–93.

Lai C-C, Shih T-P, Ko W-C, Tang H-J, Hsueh P-R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55:105924.

Lai C-C, Hsu C-K, Yen M-Y, Lee P-I, Ko W-C, Hsueh P-R, Long COVID. An inevitable sequela of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2023;56:1–9.

Kim EG, Park SK, Nho J-H. The Effect of COVID-19–Related lifestyle changes on Depression. Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19:371–9.

Mohammed LA, Aljaberi MA, Amidi A, Abdulsalam R, Lin C-Y, Hamat RA, et al. Exploring factors affecting graduate students’ satisfaction toward E-Learning in the era of the COVID-19 Crisis. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2022;12:1121–42.

Yang B, Lin Y, **ong W, Liu C, Gao H, Ho F, et al. Comparison of control and transmission of COVID-19 across epidemic waves in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024;43:100969.

Karim SSA, Karim QA. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:2126–8.

Bourmistrova NW, Solomon T, Braude P, Strawbridge R, Carter B. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:118–25.

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–60.

Aljaberi MA, Lee K-H, Alareqe NA, Qasem MA, Alsalahi A, Abdallah AM, et al. Rasch Modeling and Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis for the usability of the impact of event scale-revised (IES-R) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthc Basel Switz. 2022;10:1858.

Dragioti E, Li H, Tsitsas G, Lee KH, Choi J, Kim J, et al. A large-scale meta‐analytic atlas of mental health problems prevalence during the COVID‐19 early pandemic. J Med Virol. 2022;94:1935–49.

**ong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LMW, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:55–64.

Aljaberi MA, Al-Sharafi MA, Uzir MUH, Sabah A, Ali AM, Lee K-H, et al. Psychological toll of the COVID-19 pandemic: an In-Depth exploration of anxiety, Depression, and Insomnia and the influence of Quarantine measures on Daily Life. Healthc Basel Switz. 2023;11:2418.

Aljaberi MA, Alareqe NA, Alsalahi A, Qasem MA, Noman S, Uzir MUH, et al. A cross-sectional study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological outcomes: multiple indicators and multiple causes modeling. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0277368.

Lazarus R, Folkman S, Stress. Appraisal and Co**. Springer publishing company; 1984. pp. 1–460.

Villalpando JMG, Forcelledo HA, Castillo JLB, Sastré AJ, Rojop IEJ, Hernández VO, et al. COVID-19, Long COVID Syndrome, and Mental Health Sequelae in a Mexican Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:6970.

Matsumoto K, Hamatani S, Shimizu E, Käll A, Andersson G. Impact of post-COVID conditions on mental health: a cross-sectional study in Japan and Sweden. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:237.

The Lancet, Long COVID. 3 years in. Lancet. 2023;401:795.

Malik P, Patel K, Pinto C, Jaiswal R, Tirupathi R, Pillai S, et al. Post-acute COVID‐19 syndrome (PCS) and health‐related quality of life (HRQoL)—A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2022;94:253–62.

Sivan M, Taylor S. NICE guideline on long covid. BMJ. 2020;371:m4938.

Chen C, Haupert SR, Zimmermann L, Shi X, Fritsche LG, Mukherjee B. Global prevalence of Post-coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. J Infect Dis. 2022;226:1593–607.

Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603.

Millroth P, Frey R. Fear and anxiety in the face of COVID-19: negative dispositions towards risk and uncertainty as vulnerability factors. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;83:102454.

Del-Valle MV, López-Morales H, Andrés ML, Yerro-Avincetto M, Gelpi Trudo R, Urquijo S, et al. Intolerance of COVID-19-related uncertainty and depressive and anxiety symptoms during the pandemic: a longitudinal study in Argentina. J Anxiety Disord. 2022;86:102531.

Nelson BD, Shankman SA, Proudfit GH. Intolerance of uncertainty mediates reduced reward anticipation in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:108–13.

Han Q, Zheng B, Agostini M, Bélanger JJ, Gützkow B, Kreienkamp J, et al. Associations of risk perception of COVID-19 with emotion and mental health during the pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;284:247–55.

Nehme M, Braillard O, Alcoba G, Aebischer Perone S, Courvoisier D, Chappuis F, et al. COVID-19 symptoms: longitudinal evolution and persistence in outpatient settings. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:723–5.

Kim AW, Nyengerai T, Mendenhall E. Evaluating the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic: perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and childhood trauma predict adult depressive symptoms in urban South Africa. Psychol Med. 2022;52:1587–99.

Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Why do people worry? Personal Individ Differ. 1994;17:791–802.

Dugas MJ, Gosselin P, Ladouceur R. Intolerance of uncertainty and worry: investigating specificity in a nonclinical sample. Cogn Ther Res. 2001;25:551–8.

Nikopoulou VA, Gliatas I, Blekas A, Parlapani E, Holeva V, Tsipropoulou V, et al. Uncertainty, stress, and Resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2022;210:249–56.

Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Clinical and Surveillance Data-Dec 9, 2022, to Jan 23, 2023, China. 2023. https://en.chinacdc.cn/news/latest/202301/t20230126_263523.html. Accessed 28 Feb 2023.

Cui X, Hao Y, Tang S. Risk perception and depression in Public Health crises: evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;17:5728.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:539–44.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092.

He X, Li C, Qian J, Cui HS, Wu W. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety scale in general hospital outpatients. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2010;22:200–3.

Ahorsu DK, Lin C-Y, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. The fear of COVID-19 scale: development and initial validation. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:1537–45.

Chi X, Chen S, Chen Y, Chen D, Yu Q, Guo T, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the fear of COVID-19 Scale among Chinese Population. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:1273–88.

Carleton RN, Norton MAPJ, Asmundson GJG. Fearing the unknown: a short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:105–17.

Zhang Y, Song J, Gao Y, Wu S, Song L, Miao D. Reliability and validity of the intolerance of uncertainty scale-short form in university students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2017;25:285–8.

Edwards JR, Lambert LS. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: a general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol Methods. 2007;12:1–22.

Hayes AF. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling [White paper]. 2012. http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. Accessed 21 Mar 2023.

Perlis RH, Ognyanova K, Santillana M, Baum MA, Lazer D, Druckman J, et al. Association of Acute symptoms of COVID-19 and symptoms of depression in adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e213223.

Kim J-W, Kang H-J, Jhon M, Ryu S, Lee J-Y, Kang S-J et al. Associations between COVID-19 symptoms and psychological distress. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Ding Y, Xu J, Huang S, Li P, Lu C, **e S. Risk perception and depression in Public Health crises: evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:5728.

Blanuša J, Barzut V, Knežević J. Direct and indirect effect of intolerance of uncertainty on distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Primenj Psihol. 2021;13:473–87.

Daly M, Robinson E. Acute and longer-term psychological distress associated with testing positive for COVID-19: longitudinal evidence from a population-based study of US adults. Psychol Med. 2023;53:1603–10.

Schou TM, Joca S, Wegener G, Bay-Richter C. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19– a systematic review. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;97:328–48.

Sun Y, Wu Y, Fan S, Dal Santo T, Li L, Jiang X, et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ. 2023;380:e074224.

Naidu SB, Shah AJ, Saigal A, Smith C, Brill SE, Goldring J, et al. The high mental health burden of long COVID and its association with on-going physical and respiratory symptoms in all adults discharged from hospital. Eur Respir J. 2021;57:2004364.

Samper-Pardo M, Oliván-Blázquez B, Magallón-Botaya R, Méndez-López F, Bartolomé-Moreno C, León-Herrera S. The emotional well-being of long COVID patients in relation to their symptoms, social support and stigmatization in social and health services: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:68.

Burrai J, Barchielli B, Cricenti C, Borrelli A, D’Amato S, Santoro M, et al. Older adolescents who did or did not experience COVID-19 symptoms: associations with Mental Health, risk perception and social connection. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5006.

Malecki KMC, Keating JA, Safdar N. Crisis Communication and Public Perception of COVID-19 risk in the era of Social Media. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72:697–702.

Yang Z, **n Z. Heterogeneous risk perception amid the outbreak of COVID-19 in China: implications for economic confidence. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being. 2020;12:1000–18.

Zhao J, Ye B, Ma T. Positive information of COVID-19 and anxiety: a moderated mediation model of risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12.

Liu M, Zhang H, Huang H. Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20.

Abiddine FZE, Aljaberi MA, Gadelrab HF, Lin C-Y, Muhammed A. Mediated effects of insomnia in the association between problematic social media use and subjective well-being among university students during COVID-19 pandemic. Sleep Epidemiol. 2022;2:100030.

Andrews JL, Li M, Minihan S, Songco A, Fox E, Ladouceur CD, et al. The effect of intolerance of uncertainty on anxiety and depression, and their symptom networks, during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:261.

Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26:421–36.

Alsolais A, Alquwez N, Alotaibi KA, Alqarni AS, Almalki M, Alsolami F, et al. Risk perceptions, fear, depression, anxiety, stress and co** among Saudi nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ment Health. 2021;30:194–201.

Han MFY, Mahendran R, Yu J. Associations between fear of COVID-19, affective symptoms and risk perception among Community-Dwelling older adults during a COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. 2021;12:638831.

Khanal A, GC S, Panthee S, Paudel A, Ghimire R, Neupane G, et al. Fear, risk perception, and Engagement in Preventive behaviors for COVID-19 during Nationwide Lockdown in Nepal. Vaccines. 2022;11:29.

Lemogne C, Gouraud C, Pitron V, Ranque B. Why the hypothesis of psychological mechanisms in long COVID is worth considering. J Psychosom Res. 2023;165:111135.

Scharfenberg D, Schild A-K, Warnke C, Maier F. A Network Perspective on Neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms of the Post-COVID Syndrome. Eur J Psychol. 2022;18:350–6.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who volunteered to participate in this survey. We also would like to thank Lin **aoqiong, deputy director of Ouhai Psychological Counseling Center of Wenzhou City, Guan Ye, psychology teacher of Wenzhou No. 2 Senior High School, and Shao **aowei, Social Psychological Service Department of Kangning Hospital of Wenzhou City, for their support in the data collection process. We further thank all colleagues at Wenzhou medical university who were involved in the implementation of this study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YW, DW and ZS conceived and designed the study. ZS, ZJ, HL, KZ, and YZ edited and produced the electronic questionnaire, ZS, ZJ, KZ, XW, HL, NH, QZ, MY, YH, DW, and YW collected and analyzed the data. ZS, ZJ,and YW wrote the manuscript. ZS, ZJ, DW, WS and YW revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Kangning Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (approval number: YJ-2023-16-01). All participants were presented with study-related information and asked about their consent preferences. Informed consent was obtained from all included participants in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Z., **, Z., Zhao, K. et al. The moderated-mediation role of risk perception and intolerance of uncertainty in the association between residual symptoms and psychological distress: a cross-sectional study after COVID-19 policy lifted in China. BMC Psychiatry 24, 136 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05591-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05591-9