Abstract

Background

Childhood stunting and anemia are on the increase in many resource-constrained settings, without a counter increase in proper feeding practices such as exclusive breastfeeding. The objective of this study was to explore the prevalence of stunting, anemia and exclusive breastfeeding across African countries.

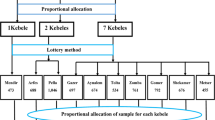

Methods

Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data from 39 African countries was analyzed. Data from under 5 children were analyzed. Forest plot was used to determine inequalities in the prevalence of the outcome variables.

Results

The prevalence of stunting was highest in Burundi (56%), Madagascar (50%) and Niger (44%). In addition, Burkina Faso (88%), Mali (82%), Cote d’Ivoire and Guinea (75% each) and Niger (73%) had the highest prevalence of anemia. Furthermore, Burundi (83%), Rwanda (81%) and Zambia (70%) had the highest exclusive breastfeeding. We found statistical significant difference in the prevalence of stunting, anemia and exclusive breastfeeding (p < 0.001). Higher prevalence of stunting and anemia were estimated among the male, rural residents, those having mothers with low education and from poor household wealth.

Conclusion

Concerted efforts are required to improve childhood health, survival and proper feeding practice. Reduced stunting and anemia could be achieved through sustained socioeconomic improvement that is shared in equity and equality among the population. Interventions aimed at increasing food availability can also aid in the reduction of hunger, particularly in impoverished communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Stunting is a common health problem among under 5 children in many resource-poor settings globally. It is defined as a deficit in height relative to a child’s age [1]. Approximately 165 million (26%) under 5 children were stunted in 2011, accounting for a 35% decrease from an estimated 253 million under 5 children in 1990 [2]. In 2016, an estimated 155 million (23%) children worldwide were stunted, with Africa accounting for more than one-third [3]. The high incidence of stunted children remains a serious public health issue, whereby more than 90% of the stunted under 5 children worldwide live in Africa and Asia. Malnutrition is thought to be responsible for nearly one-third of all childhood deaths [4]. In spite of the fact that problems linked to malnutrition affect the entire community, under 5 children are especially vulnerable due to their physiological peculiarities. Children can be vulnerable because of their need for proper feeding to enhance maturity or development of their cells, organs, systems and biomolecules to carry out the chemical and physical functions. Malnutrition reduction is critical for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly those aimed at ending poverty in all forms everywhere (SDG 1), ending hunger, achieving food security, improving nutrition, and promoting sustainable agriculture (SDG 2) and ensuring healthy lives and promoting wellbeing for all at all ages (SDG 3) [5, 6]. Due to the negative impacts of childhood malnutrition, governments have agreed to set worldwide goals to reduce chronic undernutrition (stunting) by 40% by 2025, as well as to reduce the prevalence of acute undernutrition (wasting) in under 5 children to less than 5% [7].

In resource-poor settings, suboptimal feeding affects an enormous number of individuals [8]. This improper feeding habit has several adverse effects on the populace including, poor state of health, stunted growth, low productivity, intellectual deficiency and unexpected death. Suboptimal feeding can cause adverse health effects on under 5 children, precisely from the time of conception up to their first 24 months or within their first 1,000 days of life. These poor health conditions can lead to intellectual and physical consequences [9]. Suboptimal feeding is estimated to contribute up to 34% of childhood mortality each year [10, 11]. Besides, it can impede social and economic growth within any community, particularly in poor and infrastructural deprived settings. From Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report for 2011 and 2013, as much as 842 million persons globally could not obtain their nutritional energy requirements within these three years, in comparison with about 870 million persons projected between 2010 and 2012. By implication, one out of every eight persons is at risk of chronic hunger, which is defined as a lack of sufficient food for a healthy living. The staggering number of people without adequate food, approximately 827 million live in resource-poor settings, where undernutrition is currently estimated to reach 14.3% [8].

Anemia is defined as the below-normal red blood cell count or hemoglobin level per unit volume in peripheral blood [35,36,37,38]. A possible explanation to the findings could be due to low wealth-related and mother’s education status, inadequate water supply, incidence of infectious disease and poor knowledge of nutrition, which is more prevalent in rural residence, when compared with urban counterparts [39]. In addition, mothers in the rural areas are more burdened with inadequate knowledge of infant and young child feeding practices and inadequate access to health care services [40, 41].

We found higher prevalence of stunting among male children and those with less than 24 months preceding birth interval. It seems stunting may be carried on from in utero differential growth trajectories by gender [42]. The estimates of higher prevalence of stunting among male children is in agreement with results from previous studies [36, 37, 43,44,45]. Although the reason for the sex differences in stunting is not well-known, however, there is indication that it may be due to differences in feeding and care practices between both gender [44]. Furthermore, the high prevalence of stunting among children with less than 24 months preceding birth interval, has been reported from previous studies [43, 46]. Short birth interval may be linked to improper feeding practices. The high prevalence of stunting among children in less than 24 months preceding birth interval is consistent with the findings from previous studies [46, 47]. This is likely especially among disadvantaged children. Another explanation could be mother’s inability to care for multiple children at the same time with limited household resources including food.

Our study found that mother’s education and higher household wealth status and urban residence played a significant role in lower prevalence of stunting among under 5 children. This is consistent with the findings from a previous study [48]. Access to clean potable water in higher wealth households and urban residence may have resulted to lower prevalence of stunting among the well-off. A child from a lower-educated mother suffers more from stunting than a child of a higher-educated mother. These findings are in agreement with results from previous studies [35, 36, 38, 43, 49, 50]. Educated mothers could have a better understanding of child nutrition, proper child care, hygiene, uptake of health services and they are more likely to seek expert opinion on child well-being and development. Children who came from the richest households were less likely to suffer from stunting than those from the poorest household. This corroborates with previous studies [38, 46, 51].Children from low-socioeconomic households have more likelihood to be exposed to poor nutrition, which could lead to stunting when compared with those from high socioeconomic households. The plausible explanation is the negative effect of low socioeconomic status in access to food or good nutrition, hence their uptake of adequate nutrient is low [52]. On the other hand, individuals with higher socioeconomic status can afford proper nutrition, which supports healthy living and improved child care. Notably, this leads to a reduction in malnutrition. The high prevalence of stunting reported in this study suggests more investments in social protection programmes that particularly target households with young children, which is necessary to address the high burden of stunting in African countries.

Furthermore, this study show that the prevalence of anemia among under 5 children is worrisome, ranging from 27% in Egypt to 88% in Burkina-Faso indicating that anemia is still a major public health concern in African countries. It shows that efforts in the implementations of programmes and strategies in managing infectious diseases, including deworming, malaria and iron supplementation in the region have not paid off adequately. According to the WHO classification of anemia as a public health issue, it can be severe, moderate and mild, when the prevalence is more than 40%, 20%, 5% respectively [53]. Therefore, the prevalence of anemia among under 5 children as found in this study, would be classified as severe according to the WHO cut-off point. Many previous studies have reported similar findings [19, 54, 55]. This could be due to the fact that many children were not exclusively breastfeed and the practice of inadequate feeding. Several reports have shown that poor breastfeeding practices and poor dietary diversity are linked to childhood anemia [56, 57]. Thus, when complementary feeding, such as cow milk, is timely introduced before 6 months of age, they could not substitute for iron rich foods, and thereby may lead to iron deficiency anemia. Also, malaria incidence, hookworm infestation, schistosoma and visceral leishmaniasis infection due to lack of proper sanitation and better environmental conditions could contribute to high prevalence of anemia [54].

We observed a high prevalence of anemia among rural dwellers, when compared with their urban counterparts and among male than the female children. The high prevalence of anemia among rural dwellers has been reported in similar settings [38, 58]. This could be attributed to malnutrition due to limited consumption of nutritious foods because of poverty and low socioeconomic status, poor sanitation facilities and lack of good drinking water [58], leading to increased rates of diseases and infections and subsequently increased risk of anemia. Our results mirrored findings from previous and similar studies, where male children have higher prevalence of anemia than their female counterparts [51, 54, 55, 59]. This may be due to the rapid growth and development of male children in the first few years of life, that increases their micronutrients requirement including iron than the female children [54].

This study also found socioeconomic status (wealth and education) of mother’s influence on childhood anemia. Children from low household wealth and those whose mothers had no formal education or primary education had higher prevalence of anemia than children from higher household wealth and those whose mothers had secondary and higher educational level. Previous studies reported similar findings [51, 54,55,56, 59, 60]. The possible explanation is that poor household wealth status might restrict families to access available health services, good sanitation facilities and the ability to purchase nutritious and healthy foods. Moreover, children from low socioeconomic households are more likely to experience food insecurity. Additionally, lower educated mothers are less likely to be knowledgeable about proper care for their own health and that of their children. Mother’s education has great influence in feeding practices of children and proper health care. Mothers who are educated are very conscious of their child’s health and they follow guidelines on proper feeding practices, which tends to improve their child's nutritional status.

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding in this study varied largely across African countries, ranging from 6% in Gabon to 83% in Burundi. This is line with other previous studies in similar settings and other regions [61,62,63]. A possible explanation could be dearth of knowledge about optimal breastfeeding practices. It is of utmost importance to increase communal-based behaviour change communication by means of several channels such as media and radio to educate mothers on the importance of optimal newborn and young feeding practices since suboptimal and child undernutrition remains a major issue in African countries. It is critical to focus urgently on improving children health and nutrition, particularly in rural areas and low socioeconomic status, in order to attain the SDGs aiming at zero hunger and the eradication of all kinds of malnutrition. To minimize childhood stunting and anemia in African countries, policies should focus on nutrition-specific interventions, including exclusive breastfeeding, optimal feeding practices, nutritional supplementation and child awareness-related activities, which should primarily target rural and underserved populations. Improving the nutritional status of under 5 children requires concerted efforts from both government and non-governmental organizations.

Strengths and limitation

This study has presented estimates of stunting, anemia and exclusive breastfeeding in African countries. Nationally representative large datasets were analyzed for plausible comparisons. The ability to pool many countries is a major advantage. This study can be used as a scorecard for various countries and to indicate the performance of healthcare system in various countries. This can instigate concerted efforts and new policies and programmes, as well as a call to strengthen existing programmes related to proper child feeding practices and action against hunger and poverty in general. This study would bring to limelight a call for other low and middle income countries (LMICs) to examine the uptake of exclusive breastfeeding and burden of stunting and anemia amongst others. However, we used a cross-sectional study to collect data from various countries at various points in time. Some has quite long different period (example: Eritrea was derived in 2002, whereas some countries were derived in 2017 to 2020). It might have potential factors influencing the socioeconomic condition of each country that could be linked to the variables of the study. These factors including political situation, development of health care facilities and the government’s health-policy which could lead to different capture of socioeconomic condition in each country in different period of time. As a result, the distribution of stunting and anemia may have shifted over time. This may results in sampling bias. Furthermore, the DHS does not collect data on household income or expenditure, which are traditional indicators of wealth. The assets-based wealth index used here is only a proxy for household economic status, and it does not always produce results that are comparable to those obtained from direct measurements of income and expenditure where such data are available or can be collected reliably. In addition, we do not know the proportion of stunted and anemic children, whether it is due to genetics or purely malnutrition, as other factors could have also contributed.

Conclusion

This study show high prevalence of stunting and anemia among under 5 children in Africa, particularly in rural areas and among the disadvantaged. Other factors such as being male, poor household wealth, short birth interval, low mother’s education are linked with high prevalence of stunting and anemia among under 5 children. In addition, there were sub-optimal exclusive breastfeeding practice among mothers in the studied countries. To reduce stunting and anemia among under 5 children, national public health intervention programmers and stakeholders working on improving childhood nutrition should focus on these factors. Mothers or caregivers should be educated about the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, proper feeding practices, women’s empowerment and adequate birth spacing. Programme planners and policymakers should evaluate and increase collaboration and coordination of nutritional programmes and family health programmes targeted at alleviating nutritional inadequacies.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys (DHS) and available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

WHO multicentre growth reference study group, Onis M. WHO child growth standards based on length/height, weight and age: WHO child growth standards. Acta Paediatr. 2007;95:76–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x.

United Nations Children’s Fund, World Health Organization, The World Bank. UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. (UNICEF, New York; WHO, Geneva; The World Bank, Washington, DC; 2012). [cited 12 Mar 2019]. Available: https://www.who.int/nutgrowthdb/jme_unicef_who_wb.pdf

Watkins K. A fair chance for every child. New York: UNICEF; 2016.

Desmond C, Casale D. Catch-up growth in stunted children: Definitions and predictors. Schooling CM, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0189135. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189135.

Rosa W. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. A New Era in Global Health. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826190123.ap02.

Kumar S, Kumar N, Vivekadhish S. Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Addressing unfinished agenda and strengthening sustainable development and partnership. Indian J Community Med Off Publ Indian Assoc Prev Soc Med. 2016;41:1. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.170955.

de Onis M, Dewey KG, Borghi E, Onyango AW, Blössner M, Daelmans B, et al. The World Health Organization’s global target for reducing childhood stunting by 2025: rationale and proposed actions. Matern Child Nutr. 2013;9(Suppl 2):6–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12075.

FAO. The multiple dimensions of food security. Rome: FAO; 2013.

Martorell R. Improved Nutrition in the First 1000 Days and Adult Human Capital and Health. Am J Hum Biol Off J Hum Biol Counc. 2017;29. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22952

Rice AL, Sacco L, Hyder A, Black RE. Malnutrition as an underlying cause of childhood deaths associated with infectious diseases in develo** countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;15.

You D, Hug L, Ejdemyr S, Idele P, Hogan D, Mathers C, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the un Inter-Agency Group for child mortality estimation. Lancet. 2015;386:2275–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00120-8.

Li H, **ao J, Liao M, Huang G, Zheng J, Wang H, et al. Anemia prevalence, severity and associated factors among children aged 6–71 months in rural Hunan Province, China: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:989. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09129-y.

Malako BG, Teshome MS, Belachew T. Anemia and associated factors among children aged 6–23 months in Damot Sore District, Wolaita Zone. South Ethiopia BMC Hematol. 2018;18:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12878-018-0108-1.

Bailey RL, West KP Jr, Black RE. The Epidemiology of Global Micronutrient Deficiencies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66:22–33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371618.

McLean E, Cogswell M, Egli I, Wojdyla D, de Benoist B. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO vitamin and mineral nutrition information system, 1993–2005. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:444. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008002401.

Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. Longo DL, editor. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1832–43. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1401038.

Berglund S, Domellöf M. Meeting iron needs for infants and children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:267–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0000000000000043.

Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J, Felt B, Georgieff M, Schallert T. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:S34–91. https://doi.org/10.1301/nr.2006.may.S34-S43.

Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, Wulf SK, Johns N, Lozano R, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123:615–24. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325.

Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, et al. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9.

Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Camaschella C. Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2010;142:24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.028.

Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Iron in Infection and Immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:509–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.010.

World Health Organization (WHO). Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6–8 November 2007 in Washington D.C., USA. Washington, D.C.: World Health Organization (WHO); 2008.

Kramer MS, Kakuma R. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: a systematic review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2004;554:63–77.

Burke RM, Rebolledo PA, Aceituno AM, Revollo R, Iñiguez V, Klein M, et al. Effect of infant feeding practices on iron status in a cohort study of Bolivian infants. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1066-2.

Smith ER, Hurt L, Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Fawzi W, Edmond KM, et al. Delayed breastfeeding initiation and infant survival: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Simeoni U, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0180722. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180722.

Edmond KM. Delayed breastfeeding initiation increases risk of neonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e380–6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-1496.

World Health Organization. Global targets 2025. To improve maternal, infant and young child nutrition (www.who.int/nutrition/topics/nutrition_globaltargets2025/en/. In: WHO [Internet]. [cited 19 Apr 2019]. Available: http://www.who.int/nutrition/global-target-2025/en/

World Health Organization, editor. International code of marketing of breast-milk substitutes. Geneva: World Health Organization ; Obtainable from WHO Publications Centre; 1981.

WHO. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. 2003 [cited 15 Feb 2019]. Available: www.ennonline.net/globalstrategyiycfarticle

World Health Organization, UNICEF. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. 2009. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK153471/

Corsi DJ, Neuman M, Finlay JE, Subramanian S. Demographic and health surveys: a profile. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1602–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys184.

Rutstein SO, Staveteig S. Making the Demographic and Health Surveys Wealth Index Comparable. 2014; DHS Methodological Reports No. 9. Rockville: ICF International; 2014.

World Health Organization. Nutrition landscape information system (NLiS): results of a user survey. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/328980

Fantay Gebru K, Mekonnen Haileselassie W, Haftom Temesgen A, Oumer Seid A, Afework MB. Determinants of stunting among under-five children in Ethiopia: a multilevel mixed-effects analysis of 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1545-0.

Keino S, Plasqui G, Ettyang G, van den Borne B. Determinants of stunting and overweight among young children and adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Nutr Bull. 2014;35:167–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482651403500203.

García Cruz LM, González Azpeitia G, Reyes Súarez D, Santana Rodríguez A, LoroFerrer JF, Serra-Majem L. Factors sths from the Central Region of Mozambique. Nutrients. 2017;9:491. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu9050491.

Ekholuenetale M, Tudeme G, Onikan A, Ekholuenetale CE. Socioeconomic inequalities in hidden hunger, undernutrition, and overweight among under-five children in 35 sub-Saharan Africa countries. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-019-0034-5.

Paciorek CJ, Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Ezzati M. Children’s height and weight in rural and urban populations in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:e300–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70109-8.

Nankumbi J, Muliira JK. Barriers to infant and child-feeding practices: a qualitative study of primary caregivers in Rural Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33:106–16.

Egata G, Berhane Y, Worku A. Predictors of non-exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months among rural mothers in east Ethiopia: a community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J. 2013;8:8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-8-8.

Samuel A, Osendarp SJM, Feskens EJM, Lelisa A, Adish A, Kebede A, et al. Gender differences in nutritional status and determinants among infants (6–11 m): a cross-sectional study in two regions in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12772-2.

Nshimyiryo A, Hedt-Gauthier B, Mutaganzwa C, Kirk CM, Beck K, Ndayisaba A, et al. Risk factors for stunting among children under five years: a cross-sectional population-based study in Rwanda using the 2015 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6504-z.

Wamani H, Åstrøm AN, Peterson S, Tumwine JK, Tylleskär T. Boys are more stunted than girls in Sub-Saharan Africa: a meta-analysis of 16 demographic and health surveys. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-7-17.

Akram R, Sultana M, Ali N, Sheikh N, Sarker AR. Prevalence and determinants of stunting among preschool children and its urban-rural disparities in Bangladesh. Food Nutr Bull. 2018;39:521–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0379572118794770.

Fenta HM, Workie DL, Zike DT, Taye BW, Swain PK. Determinants of stunting among under-five years children in Ethiopia from the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey: application of ordinal logistic regression model using complex sampling designs. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8:404–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2019.09.011.

Sultana P, Rahman MdM, Akter J. Correlates of stunting among under-five children in Bangladesh: a multilevel approach. BMC Nutr. 2019;5:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-019-0304-9.

Namirembe G, Ghosh S, Ausman LM, Shrestha R, Zaharia S, Bashaasha B, et al. Child stunting starts in utero: Growth trajectories and determinants in Ugandan infants. Matern Child Nutr. 2022; e13359. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13359

Semali IA, Tengia-Kessy A, Mmbaga EJ, Leyna G. Prevalence and determinants of stunting in under-five children in central Tanzania: remaining threats to achieving millennium development goal 4. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2507-6.

Zhu W, Zhu S, Sunguya BF, Huang J. Urban-rural disparities in the magnitude and determinants of stunting among children under five in Tanzania: based on Tanzania demographic and health surveys 1991–2016. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:5184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105184.

Sunguya BF, Zhu S, Paulo LS, Ntoga B, Abdallah F, Assey V, et al. Regional disparities in the decline of anemia and remaining challenges among children in Tanzania: analyses of the Tanzania demographic and health survey 2004–2015. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3492. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103492.

Derso T, Tariku A, Biks GA, Wassie MM. Stunting, wasting and associated factors among children aged 6–24 months in Dabat health and demographic surveillance system site: A community based cross-sectional study in Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17:96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-017-0848-2.

Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005. [cited 12 Feb 2022]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241596657

Tesema GA, Worku MG, Tessema ZT, Teshale AB, Alem AZ, Yeshaw Y, et al. Prevalence and determinants of severity levels of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0249978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249978.

Moschovis PP, Wiens MO, Arlington L, Antsygina O, Hayden D, Dzik W, et al. Individual, maternal and household risk factors for anaemia among young children in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019654. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019654.

Woldie H, Kebede Y, Tariku A. Factors Associated with Anemia among Children Aged 6–23 Months Attending Growth Monitoring at Tsitsika Health Center, Wag-Himra Zone. Northeast Ethiopia J Nutr Metab. 2015;2015:e928632. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/928632.

Malako BG, Asamoah BO, Tadesse M, Hussen R, Gebre MT. Stunting and anemia among children 6–23 months old in Damot Sore district, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Nutr. 2019;5:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-018-0268-1.

Ewusie JE, Ahiadeke C, Beyene J, Hamid JS. Prevalence of anemia among under-5 children in the Ghanaian population: estimates from the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:626. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-626.

Roberts DJ, Matthews G, Snow RW, Zewotir T, Sartorius B. Investigating the spatial variation and risk factors of childhood anaemia in four sub-Saharan African countries. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8189-8.

Shenton LM, Jones AD, Wilson ML. Factors associated with anemia status among children Aged 6–59 months in Ghana, 2003–2014. Matern Child Health J. 2020;24:483–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-019-02865-7.

Onah S, Osuorah DIC, Ebenebe J, Ezechukwu C, Ekwochi U, Ndukwu I. Infant feeding practices and maternal socio-demographic factors that influence practice of exclusive breastfeeding among mothers in Nnewi South-East Nigeria: a cross-sectional and analytical study. Int Breastfeed J. 2014;9:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4358-9-6.

Woldeamanuel BT. Trends and factors associated to early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding in Ethiopia: evidence from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-019-0248-3.

Ekholuenetale M, Mistry SK, Chimoriya R, Nash S, Doyizode A, Arora A. Socioeconomic inequalities in early initiation and exclusive breastfeeding practices in Bangladesh: findings from the 2018 demographic and health survey. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00420-1

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the MEASURE DHS project for the approval and access to the original data.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ME contributed to the conceptualization, review of literature, initial manuscript preparation, study design, data analysis and wrote the results. OCO, CIN, AB prepared the manuscript, wrote the results and discussed the findings. ME, OCO, CIN, AB read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a secondary data analysis, which is publicly available, approval was sought from MEASURE DHS/ICF International and permission was granted for this use. The original DHS data were collected in conformity with international and national ethical guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from mothers/caregivers and data were recorded anonymously at the time of data collection during the data collection. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://dhsprogram.com/data/availabledatasets.cfm

Competing interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekholuenetale, M., Okonji, O.C., Nzoputam, C.I. et al. Inequalities in the prevalence of stunting, anemia and exclusive breastfeeding among African children. BMC Pediatr 22, 333 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03395-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-022-03395-y