Abstract

Background

We aimed to investigate the clinical characteristics of severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection in children.

Methods

We retrospectively analysed data concerning 64 paediatric patients with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia who had been treated at our hospital. The patients were divided into observation (44 patients) and control (20 patients) groups, based on the presence or absence of concomitant bacterial infection, and clinical data were compared between the groups.

Results

The mean age in the observation group was 2.71 ± 1.44 years, 42 (95.45%) were aged ≤ 5 years, and 18 (40.9%) had underlying diseases. The mean age in the control group was 4.05 ± 2.21 years, 13 (65%) were aged ≤ 5 years, and 3 (15%) had underlying diseases. There was a statistically significant difference in patient age and the proportion of patients with underlying diseases (P < 0.05). The observation group had higher duration of fever values, a higher number of patients with duration of fever ≥ 7 days, a higher incidence of gas**, and a higher incidence of seizures/consciousness disturbance, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Secondary bacterial infections in the observation group were mainly due to gram-negative bacteria, with Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis being the most common pathogens. The observation group had a higher proportion of patients treated in the paediatric intensive care unit and a longer hospital stay, and the differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Conclusion

Severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection was more common in children aged ≤ 5 years. Younger patients with underlying diseases were more susceptible to bacterial infection (mainly due to gram-negative bacteria). The timely administration of neuraminidase inhibitors and antibiotics against susceptible bacteria is likely to help improve cure rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

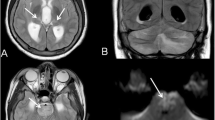

Influenza, also known as the ‘flu, causes periodic pandemics. It has been estimated that seasonal influenza affects approximately 1 billion people worldwide every year. Among paediatric populations, the influenza infection rate has been reported to be as high as 20–30% [1, 2], which is considerably higher than that in adults. Pneumonia is a common cause of hospitalisation in patients infected with the influenza virus, and infected children have a high tendency to develop severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia, which may be life-threatening [3, 4]. Previous studies have found that patients infected with the influenza virus are prone to develo** secondary bacterial infection, which usually occurs within 7 days of influenza virus infection and may aggravate disease severity and affect the prognoses of such patients [5]. This issue is particularly prominent in the paediatric influenza pneumonia population. Given the current lack of studies on severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection in children in China, we aimed to analyse the clinical characteristics of paediatric patients with concomitant severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia and bacterial infection who had been treated at ** in 31 (70.45%), seizures/consciousness disturbance in 26 (59.09%), and audible pulmonary rales in 36 (81.82%) patients. In 23 (52.27%) patients, pulmonary imaging results suggested the presence of pulmonary consolidation and atelectasis. Moreover, 2 patients had respiratory failure, 3 had septic shock, 2 had toxic encephalopathy, 3 had liver injury, 1 had metabolic acidosis, and 1 patient had tracheal stenosis.

In the control group, all 20 patients developed pyrexia with a peak temperature of 39.3 °C (range, 39–40.2 °C) and a pyrexia duration of 5 (3–6) days, and 4 (20%) patients had a pyrexia duration of ≥ 7 days. Other clinical symptoms included cough in all patients, gas** in 8 (40%), seizures/consciousness disturbance in 5 (25%), and audible pulmonary rales in 15 (75%) patients. In 10 (50%) patients, pulmonary imaging results suggested the presence of pulmonary consolidation and atelectasis. There was also 1 patient with respiratory failure, 1 in septic shock, 2 with brainstem encephalitis, 1 with liver injury, 1 with myocardial damage, and 2 with agranulocytosis. Table 2 shows a comparison of clinical characteristics between the observation and control groups.

Bacterial culture and susceptibility to antibiotics

A total of 46 positive culture specimens were collected from the 44 patients in the observation group, of which 44 were oronasal sputum specimens and 2 were alveolar lavage fluid specimens. In 2 patients, positive cultures were detected in both the oronasal sputum and alveolar lavage fluid specimens. All H. influenzae cultures were susceptible to ceftriaxone, cefotaxime sodium, and meropenem, showing resistance rates of 61.7%, 76.6%, 27.7%, and 6.4% to ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, cefuroxime, and ampicillin/sulbactam, respectively. All M. catarrhalis cultures were susceptible to ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/sulbactam, and ciprofloxacin, and exhibited resistance rates of 59.4% and 13.3% to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole, respectively.

Treatment and outcomes

The observation group patients were treated with neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs), with 36 patients having received oseltamivir via oral administration/nasal feeding, 6 patients having received peramivir via intravenous infusion, and 2 patients having received oral oseltamivir followed by peramivir via intravenous infusion. In 31 patients, NAIs were used for the first time at > 48 h after disease onset. Antibiotics were administered to all patients over a duration of 7 (range, 5–8) days. Eighteen (40.9%) patients underwent fibreoptic bronchoalveolar lavage therapy and 26 (59.1%) were treated in the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU). The average length of hospital stay in the observation group was 12 (range, 9–14) days. One patient aged ≤ 5 years who had underlying epilepsy died of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

The control group patients were also treated with NAIs, with 19 patients receiving oseltamivir via oral administration/nasal feeding and 1 patient receiving oral oseltamivir followed by peramivir via intravenous infusion. In 12 patients, NAIs were used for the first time at > 48 h after disease onset. Six (30%) patients underwent fibreoptic bronchoalveolar lavage therapy and 5 (25%) were treated in the PICU. The control group had an average length of hospital stay of 7 (range, 6–12.8) days and no patients died. Table 3 shows a comparison of treatment and outcomes between the observation and control groups.

Discussion

Pneumonia due to influenza virus infection is a common cause of hospitalisation among children. In severe cases, patients may experience respiratory failure, septic shock, or even life-threatening conditions [3, 4, 6]. One study reported that > 10,000 children around the world aged ≤ 5 years die from influenza virus-associated pneumonia annually, with most being paediatric patients with influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection [7]. Therefore, clinicians should pay greater attention to concomitant influenza virus-associated pneumonia and bacterial infection in children, particularly in children with severe illness. In our study, the average age of the observation group was significantly lower than that of the control group, indicating that younger age is associated with a higher risk of secondary bacterial infection in severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia. We also found that children aged ≤ 5 years comprised 95.5% (42/44) of the patients in the observation group, which was similar to the findings reported by Zhou et al. [1]. Besides, the observation group had a higher proportion of patients with underlying diseases than the control group. There was also one death in the observation group, which occurred in a patient with a history of epilepsy.

Given these findings, the possibility of concomitant bacterial infection in patients aged ≤ 5 years with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia should be taken seriously. Relevant guidelines developed by experts in China and other countries have stated that children aged ≤ 5 years are not only susceptible to influenza virus infection but are also a high-risk population for secondary bacterial infection [12]. Therefore, particular attention should be paid to paediatric patients with influenza and underlying diseases in clinical practice.

The reported incidence rates of influenza virus infection complicated with bacterial infection have varied over recent years. In a 2009 multicentre study conducted at 17 hospitals in China, 14.0% of children with influenza virus infection had a concomitant bacterial infection [13]. A 2018 study involving 838 paediatric patients with influenza in 35 PICUs in the United States reported the presence of concomitant bacterial infection in 274 (32.7%) patients, [14] a higher incidence rate than that reported in the 2009 study. Our results showed that the proportion of patients with influenza virus infection and with concomitant bacterial infection was 68.74% (44/64), which was higher than the aforementioned incidence rates. Certain biases may exist in our study due to its single-centre design and small sample size; however, the overall increasing trend in the proportion of paediatric patients with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection cannot be ignored, especially in severe paediatric cases. We also observed clear changes in the bacterial spectra of patients with concomitant influenza and bacterial infection. The previously mentioned multicentre study concerning patients with influenza and bacterial coinfection in China found that gram-positive bacteria accounted for > 60% of all cases [13]. The results of a meta-analysis of > 3000 cases of influenza and bacterial coinfection in various countries in 2003–2014 also showed that gram-positive bacteria predominated, with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus infections being the most common [15]. Our results differed from those of the aforementioned studies in that gram-negative bacterial infections accounted for 75% (33/44) of patients with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection, with H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis accounting for 40.9% (18/44) and 27.3% (12/44) of patients, respectively. Possible reasons for the predominance of gram-negative bacteria in the present study are as follows. First, in recent years, changes have occurred in the bacterial spectra of lower respiratory tract infections in children, causing the incidence rate of gram-negative bacterial infections to exceed that of gram-positive bacterial infections. A 2015 Chinese study by Li et al. [16] reported that gram-negative bacteria accounted for approximately 74.1% of lower respiratory tract infections in children, which was significantly higher than the incidence rate for gram-positive bacterial infections. In 2019, Lim et al. [17] reported that, in Korea, H. influenzae accounted for 25.6% of cases of community-acquired pneumonia with viral and bacterial coinfection and that the rate of coinfection exhibited an increasing trend, which is consistent with the H. influenzae infection rate of 40.9% (18/44) observed in our study. Second, differences in bacterial strains causing secondary bacterial infections may exist between patients with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia and those with common influenza virus infection. Kim et al. [18] reported that secondary bacterial infections in mechanically ventilated patients with influenza type A infection were most commonly due to Acinetobacter baumannii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which are all gram-negative bacteria. Third, factors such as differences in regional climate and sample size may also affect the conclusions obtained in different studies. Nonetheless, paying attention to changes in the bacterial spectra of concomitant bacterial infection in paediatric influenza virus-associated pneumonia is of practical significance for early diagnosis confirmation and timely administration of targeted antibacterial treatment.

Influenza and bacterial coinfection lack specific manifestations in the early stage and can only be confirmed through a combined analysis of clinical symptoms, aetiology, and other laboratory examination results. Our findings showed that patients in the observation group were more prone to longer pyrexia duration and clinical symptoms such as gas**, seizures, and consciousness disturbance than patients in the control group. This suggests that the development of the aforementioned symptoms in children with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia may serve as a warning sign of the possibility of concomitant bacterial infection. The observation group also exhibited significant increases in inflammatory indicators such as C-reactive protein and procalcitonin levels, indicating that these elevated levels in paediatric patients with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia may assist in the early identification of bacterial infection. In addition, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were also significantly elevated in the observation group compared with the control group. A retrospective study of Japanese patients with pneumonia showed that the LDH level can serve as an indicator of lung tissue damage in children [19]. Our study results also suggest that LDH may also be used as a predictive indicator of the presence or absence of concomitant bacterial infection in children with severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia. However, further deliberation is required for the establishment of specific quantitative criteria.

In this study, the bacterial species most commonly detected in the patients were H. influenzae and M. catarrhalis. We found that H. influenzae was susceptible to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, and meropenem but exhibited a resistance rate of 61.7% to ampicillin, which is close to the resistance rate of 69.19% reported by Mai et al. [20]. This result suggests that ampicillin may no longer be considered the drug of choice for the treatment of H. influenzae infection. Third-generation cephalosporins may instead be selected for initial empiric treatment. M. catarrhalis was susceptible to ampicillin/sulbactam, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, and ciprofloxacin, and exhibited resistance rates of 59.4% and 13.3% to ampicillin and co-trimoxazole, respectively. Therefore, we recommend the use of penicillin-based compound formulations as first-choice drugs for initial empiric treatment of M. catarrhalis infection in children. Ricketson et al. [21] reported that patients who did not receive standardised antibiotic treatment had a 5.6-fold increase in case fatality rates compared with a standardised treatment group. Similarly, we found that satisfactory therapeutic effects could be achieved with early administration of antibiotics against susceptible bacteria in the observation group.

This study had some limitations. First, this was a single-centre retrospective study that included patients from the past four years. Therefore, the data used for analysis were limited and may not fully reflect the characteristics of severe influenza virus-associated pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection in children. Second, all patients included in this study originated from ** during the early stage; elevated C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and LDH levels; and non-improvement of disease condition or relapse following an initial response when antiviral treatment was administered. Once the presence of bacterial infection has been confirmed, empiric antibiotic therapy should be initiated as soon as possible.