Abstract

Objective

In this study, we aimed to assess the synergistic effects of cognitive frailty (CF) and comorbidity on disability among older adults.

Methods

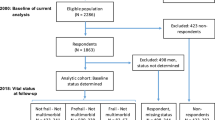

Out of the 1318 participants from the Malaysian Towards Useful Aging (TUA) study, only 400 were included in the five-year follow-up analysis. A comprehensive interview-based questionnaire covering socio-demographic information, health status, biochemical indices, cognitive and physical function, and psychosocial factors was administered. Binary logistic regression analysis was employed to estimate the independent and combined odd ratios (ORs). Measures such as the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI), the attributable proportion of risk due to the interaction, and the synergy index were used to assess the interaction between CF and comorbidity.

Results

Participants with CF (24.1%) were more likely to report disability compared to those without CF (10.3%). Synergistic effects impacting disability were observed between CF and osteoarthritis (OA) (OR: 6.675, 95% CI: 1.057–42.158; RERI: 1.501, 95% CI: 1.400–1.570), CF and heart diseases (HD) (OR: 3.480, 95% CI: 1.378–8.786; RERI: 0.875, 95% CI: 0.831–0.919), CF and depressive symptoms (OR: 3.443, 95% CI: 1.065–11.126; RERI: 0.806, 95% CI: 0.753–0.859), and between CF and diabetes mellitus (DM) (OR: 2.904, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.487–5.671; RERI: 0.607, 95% CI: 0.577–0.637).

Conclusion

These findings highlight the synergism between the co-existence of CF and comorbidity, including OA, HD, DM, and depressive symptoms, on disability in older adults. Screening, assessing, and managing comorbidities, especially OA, HD, DM and depressive symptoms, when managing older adults with CF are crucial for reducing the risk of or preventing the development of disability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Approximately 15% of the global population is estimated to have some form of disability due to the rapid rise in the global aging population and a parallel increase in the prevalence of chronic health conditions [1]. With the progressive surge in longevity and lifespan, disability is steadily becoming an integral factor of disease burden worldwide. Several chronic diseases, including ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and dementia in mid-life or late life, have been identified as causes of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), which is the sum of years lost due to premature mortality [2]. Functional disability in late life appears to be linked with gradual age-related deterioration and the coexistence of multiple diseases [3, 4]. Consequently, this strongly predicts future needs for assisted living and long-term nursing care, which heavily burden the healthcare system in addition to economic and personal burdens [2]. Disability risk factors include gender, age, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, and chronic diseases [5, 6]. This phenomenon is also a known adverse outcome of both frailty and cognitive impairment in older adults [7, 8].

Notably, frailty and cognitive impairment were often viewed as two independent concepts in previous studies until cognitive frailty (CF) was introduced by the consensus group of the International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) and the International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics (IAGG) [9]. The simultaneous coexistence of physical frailty and cognitive impairment, or CF, seems to entail a greater risk of all-cause mortality and adverse health outcomes than their respective effects alone, as reported in both community-based and population-based studies [10,11,12]. The higher prevalence and incidence of CF, specifically among community-dwelling Malaysian older adults (39.6%; 7.1 per 100 person-years), has become a worrisome issue as those with CF are predicted to develop disability incidence by fivefold as compared to frailty and mild cognitive impairment on its own, based on five years cohort study [13,14,15].

Both physical frailty and cognitive impairment have been identified as risk factors for physical disability [8, 15], where these may act independently or, more often, in synergistic combinations. Individuals with CF are more likely to experience difficulties in performing activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) by two- to fivefold, leading to functional impairment and dependence on others for care [16]. Chronic low-grade inflammation, often observed in individuals with CF, can impair the regeneration of muscle tissue following injury and exacerbate muscle mass loss and functional decline, limiting an individual’s ability to perform activities of daily living and subsequent disability incidence [15, 17].

Furthermore, the presence of chronic diseases in older adults with CF further exacerbates the decline of physiological reserve function in multiple systems, thereby increasing the risk of adverse health outcomes [47]. Therefore, integrating exercises with cognitive stimulation, nutritional support, and psychosocial interventions holds promise in reducing disability risk associated with comorbidities while enhancing cognitive function and emotional well-being.

This study also demonstrated the synergistic effect of older adults with CF and heart diseases on the incidence of disability by more than three-fold, as compared to those without both conditions. Heart diseases have been identified as the most common self-reported cause of the overall decline in functional status [48], which in turn progresses to disability in later life. Besides, research has demonstrated that reduced cerebral blood flow resulting from decreased cardiac output in individuals with heart failure can potentially lead to both sarcopenia and cognitive impairment [49, 50]. Furthermore, modifiable risk factors such as educational level, exercise capacity, sleep disturbance, and depressive symptoms are associated with an elevated likelihood of cognitive decline among individuals with heart failure, which can be addressed through non-pharmacological interventions [51, 52]. It has also been demonstrated that a combined program of aerobic exercise and cognitive training significantly improved verbal memory, self-care management, quality of life, and functional capacity in persons with heart failure [51, 53]. Thus, these findings highlights the potential effectiveness of multifaceted non-pharmacological interventions improving various aspects of well-being, with the potential to act as preventive measures against disability in later life.

Next, this study also reported that CF and depression had synergistic effects on disability incidence by three-fold greater than those who did not report either condition. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that the prevalence of CF with depression in older adults is high wherein both are mutually affected and share common physiologic processes (e.g. inflammation) and risk factors (e.g. physical inactivity) [54, 55]. Therefore, a possible pathological mechanism underlying these associations could be due to high inflammation levels, such as elevated interleukin-6 (IL-6), which impacts future adverse health problems, including the incidence of disability among older adults [56, 57]. Depressive symptoms have been identified as a significant predictor of CF incidence in previous research [13, 14], highlighting the importance of addressing depression in older individuals. Implementing interventions targeting depressive symptoms is crucial not only for mental health but also as a preventive measure against disability. Non-pharmacological interventions like psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and psychosocial support programs can be instrumental in treating depression among older adults [58], aiming to alleviate symptoms and enhance overall well-being, potentially reducing the risk of cognitive frailty and associated disabilities.

Among the older adults reported to have CF, diabetes mellitus demonstrated synergistic relationships with the incidence of disability. The combined effect of these two conditions is three-fold higher than these risk factors on its own, highlighting the importance of addressing the medical comorbidities in CF interventions. This is consistent with a published report that cognitive impairment and physical frailty are powerful prognostic factors in predicting disability and mortality among older adults with diabetes mellitus [59]. Metabolic and vascular dysregulation, characterized by hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, and chronic inflammation, have been identified as the primary biological mechanisms underlying the observed synergistic relationship between diabetes and CF [60, 61]. Additionally, hypoglycemia in individuals with diabetes is linked to CF, depressive symptoms, low psychological well-being, and reduced quality of life. These factors can impede the performance of daily activities and increase the risk of disability [19]. Hence, prioritizing mental well-being through personalized care plans that include counseling, support groups, and fostering community connections is essential for improving overall resilience and quality of life among older adults confronting both cognitive frailty and diabetes mellitus.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind which specifically looks into the synergistic effects of individual comorbidities that co-occur with CF in Malaysian older adults on disability indices. After accounting for a broad range of confounding factors, the results of this longitudinal study shed light on the intricate and dynamic cause-and-effect relationship between the synergistic effects of CF and comorbidities on disability incidence among older adults in Malaysia. While the independent effects of CF and chronic diseases are expected, our findings are important as they highlight the multiplicative effects of co-existing CF and medical comorbidities on disability incidence. This study is not without its limitations. Firstly, data regarding the presence of comorbidities were self-reported which may be influenced by misunderstanding or inaccurate responses from the participants. However, it should be noted that self-reported disease diagnoses have been used widely and reported to be valid [29]. Secondly, it is important to note that we did not consider the interval between the initial diagnosis of comorbidities and the index date, as older adults with CF may not accurately provide this information. However, this data could have been obtained from the medical records of older adults, with prior instructions for them to bring along their medical follow-up records if available. Thirdly, the generalizability of the current findings to the general population may not be possible owing to the smaller sample size included in this analysis. Nonetheless, this study provides novel findings and can be a step** stone for more in-depth, explorative future research undertakings. Hence, there is a need for future large-scale longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods among older adults to validate our current findings. In future studies with a larger sample size, CF could be defined into several subtypes, and data could be stratified based on age, sex, educational levels, and regions to underscore the significance of cognitive frailty. Additionally, it is recommended that future research should prioritize interventional randomized controlled trials targeting both CF and comorbidities simultaneously as a proactive strategy to prevent, delay, or manage poor health outcomes among older adults.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of our study highlights the synergistic effects of CF and comorbidities, such as OA, HD, depressive symptoms, and diabetes mellitus, heightening the risk of disability in later life. Early identification of individuals at risk for both CF and comorbidities is crucial for preventing or mitigating disability in older populations. In addition, implementing interdisciplinary interventions targeting CF and associated comorbidities can delay disability onset, emphasizing the importance of integrated care models and community-based support systems to enhance the well-being of older adults.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of study participants but are available from the corresponding author at reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles. 2014 (2014). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128038/9789241507509_eng.pdf [Accessed March 15, 2023].

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Diseases and Injuries Collaborators Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1204–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9.

McHugh D, Gil J. Senescence and aging: causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol. 2018;217(1):65–77. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201708092.

Fidecki W, Wysokiński M, Ochap M, Wrońska I, Przylepa K, Kulina D, et al. Selected aspects of life quality of nurses at neurological wards. JNNN. 2016;5(4):151–5. https://doi.org/10.15225/PNN.2016.5.4.4.

Song H. Risk factors for functional disability among community dwelling elderly. Korean J Health Educ Promotion. 2015;32(3):109–20. https://doi.org/10.14367/kjhep.2015.32.3.109.

Liu H, Jiao J, Zhu C, et al. Potential associated factors of functional disability in Chinese older inpatients: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:319. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01738-x.

Makizako H, Shimada H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Suzuki T. Impact of physical frailty on disability in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ open. 2015;5(9):e008462. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008462.

Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Tsutsumimoto K, Lee S, Suzuki T. Cognitive impairment and disability in older Japanese adults. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158720.

Kelaiditi E, Cesari M, Canevelli M, van Kan GA, Ousset PJ, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Ritz P, Duveau F, Soto ME, Provencher V, Nourhashemi F, Salvà A, Robert P, Andrieu S, Rolland Y, Touchon J, Fitten JL, Vellas B. (2013). Cognitive frailty: rational and definition from an (I.A.N.A./I.A.G.G.) international consensus group. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 17(9):726–734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-013-0367-2.

St John PD, Tyas SL, Griffith LE, Menec V. The cumulative effect of frailty and cognition on mortality - results of a prospective cohort study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(4):535–43. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216002088.

Feng L, Nyunt MS, Gao Q, Feng L, Lee TS, Tsoi T, Chong MS, Lim WS, Collinson S, Yap P, Yap KB, Ng TP. (2017). Physical Frailty, Cognitive Impairment, and the risk of neurocognitive disorder in the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing studies. The journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 72(3):369–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glw050.

Esteban-Cornejo I, Cabanas-Sánchez V, Higueras-Fresnillo S, Ortega FB, Kramer AF, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Martinez-Gomez D. (2019). Cognitive frailty and mortality in a national cohort of older adults: The role of physical activity. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 94(7):1180–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.027.

Rivan NFM, Shahar S, Rajab NF, Singh D, Din NC, Hazlina M, Hamid T. Cognitive frailty among Malaysian older adults: baseline findings from the LRGS TUA cohort study. Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:1343–52. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S211027.

Rivan NFM, Shahar S, Rajab NF, Singh D, Che Din N, Mahadzir H, Mohamed Sakian NI, Ishak WS, Abd Rahman MH, Mohammed Z, You YX. Incidence and predictors of cognitive Frailty among older adults: A Community-based Longitudinal Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1547. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051547.

Rivan NFM, Singh DKA, Shahar S, et al. Cognitive frailty is a robust predictor of falls, injuries, and disability among community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:593. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02525-y.

Tang KF, Teh PL, Lee SWH. Cognitive Frailty and Functional Disability among Community-Dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Innov Aging. 2023;7(1):igad005. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igad005. PMID: 36908650; PMCID: PMC9999676.

Solfrizzi V, Scafato E, Lozupone M, Seripa D, Giannini M, Sardone R, et al. Additive role of a potentially reversible cognitive frailty model and inflammatory state on the risk of disability: the Italian longitudinal study on aging. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(11):1236–48.

Deng Y, Li N, Wang Y, **ong C, Zou X. Risk factors and Prediction Nomogram of Cognitive Frailty with Diabetes in the Elderly. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2023;16:3175–85. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S426315. PMID: 37867632; PMCID: PMC10588717.

Abdelhafiz AH, Sinclair AJ. Cognitive Frailty in older people with type 2 diabetes Mellitus: the Central Role of Hypoglycaemia and the need for Prevention. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19(4):15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-019-1135-4.

Wang C, Zhang J, Hu C, Wang Y. Prevalence and risk factors for cognitive Frailty in Aging Hypertensive patients in China. Brain Sci. 2021;11(8):1018. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11081018.

Faulkner KM, Uchmanowicz I, Lisiak M, Cichoń E, Cyrkot T, Szczepanowski R. Cognition and Frailty in patients with heart failure: a systematic review of the Association between Frailty and Cognitive Impairment. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:713386. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713386. PMID: 34276454; PMCID: PMC8282927.

Sheridan PE, Mair CA, Quiñones AR. Associations between prevalent multimorbidity combinations and prospective disability and self-rated health among older adults in Europe. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1214-z.

Lu J, Guo QQ, Wang Y, Zuo ZX, Li YY. The Evolutionary Stage of Cognitive Frailty and Its Changing Characteristics in Old Adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(4):467–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1560-8. PMID: 33786564.

Shahar S, Omar A, Vanoh D, Hamid TA, Mukari SZ, Din NC, Rajab NF, Mohammed Z, Ibrahim R, Loo WH, Meramat A, Kamaruddin MZ, Bagat MF, Razali R. Approaches in methodology for population-based longitudinal study on neuroprotective model for healthy longevity (TUA) among Malaysian older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;28(6):1089–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0511-4.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146.

Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62.

Petersen RC, Caracciolo B, Brayne C, Gauthier S, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275(3):214–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12190.

Lee LK, Shahar S, Chin AV, Mohd Yusoff NA, Rajab NF, Abdul Aziz S. Prevalence of gender disparities and predictors affecting the occurrence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54:185–91.

Simpson CF, Boyd CM, Carlson MC, Griswold ME, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Agreement between self-report of disease diagnoses and medical record validation in disabled older women: factors that modify agreement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):123–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52021.x.

Teh EE, Hasanah CI. (2004). Validation of malay version of geriatric Depression Scale among Elderly inpatients. Penang Hospital and School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, September 2004. Available online at: https://www.priory.com/psych/MalayGDS.htm [Accessed on March 20, 2023].

Andrews G, Kemp A, Sunderland M, Von Korff M, Ustun TB. Normative data for the 12 item WHO disability assessment schedule 2.0. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(12):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0008343.

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(6):705–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b.

Graf C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living scale. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):52–62.

Rothman KJ. Measuring interactions. Epidemiology: an introduction. Oxford: University; 2002. pp. 168–80.

Andersson T, Alfredsson L, Kallberg H, et al. Calculating measures of biological interaction. Eur J Epidemiol. 2005;20:575–9.

Greenland S, Lash TL, Rothman KJ. Concepts of interaction. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL, editors. Modern epidemiology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 71–83.

Ho C, Feng L, Fam J, et al. Coexisting medical comorbidity and depression: multiplicative effects on health outcomes in older adults. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1221–9.

Lee WJ, Peng LN, Lin CH, Lin HP, Loh CH, Chen LK. The synergic effects of frailty on disability associated with urbanization, multimorbidity, and mental health: implications for public health and medical care. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14125. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32537-5.

**ang X, An R. The impact of cognitive impairment and Comorbid Depression on disability, Health Care utilization, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(11):1245–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400511.

Stubbs B, Binnekade T, Eggermont L, et al. Pain and the risk for falls in community-dwelling older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:175–e879.

Stubbs B, Aluko Y, Myint PK, Smith TO. (2016). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing, 45(2):228–35. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26795974 (Accessed January 15, 2023).

Arnold CM, Faulkner RA. The history of falls and the association of the timed up and go test to falls and near-falls in older adults with hip osteoarthritis. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:17.

Lee AC, Harvey WF, Wong JB, Price LL, Han X, Chung M, Driban JB, Morgan LPK, Morgan NL, Wang C. Effects of Tai Chi versus physical therapy on mindfulness in knee osteoarthritis. Mindfulness (N Y). 2017;8(5):1195–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0692-3.

Hall M, Dobson F, Van Ginckel A, Nelligan RK, Collins NJ, Smith MD, Ross MH, Smits E, Bennell KL. Comparative effectiveness of exercise programs for psychological well-being in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51(5):1023–32.

Yang GY, Hunter J, Bu FL, Hao WL, Zhang H, Wayne PM, Liu JP. Determining the safety and effectiveness of Tai Chi: a critical overview of 210 systematic reviews of controlled clinical trials. Syst Rev. 2022;11(1):260.

Rosenberg MD, Scheinost D, Greene AS, Avery EW, Kwon YH, Finn ES, Ramani R, Qiu M, Constable RT, Chun MM. Functional connectivity predicts changes in attention observed across minutes, days, and months. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(7):3797–807. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912226117. Epub 2020 Feb 4. PMID: 32019892; PMCID: PMC7035597.

Murukesu RR, Singh DKA, Shahar S, Subramaniam P. Physical activity patterns, Psychosocial Well-Being and co** strategies among older persons with cognitive Frailty of the WE-RISE trial throughout the COVID-19 Movement Control Order. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:415–29. PMID: 33692620; PMCID: PMC7939500.

Kucharska-Newton A, Griswold M, Yao ZH, Foraker R, Rose K, Rosamond W, Wagenknecht L, Koton S, Pompeii L, Windham BG. Cardiovascular Disease and patterns of change in functional Status over 15 years: findings from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e004144. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004144.

Josiak K, Jankowska EA, Piepoli MF, Banasiak W, Ponikowski P. Skeletal myopathy in patients with chronic heart failure: significance of anabolic-androgenic hormones. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2014;5:287–96.

Suzuki H, Matsumoto Y, Ota H, Sugimura K, Takahashi J, Ito K, et al. Hippocampal blood flow abnormality associated with depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in patients with chronic heart failure. Circ J. 2016;80:1773–80.

Gary, R. A., Paul, S., Corwin, E., Butts, B., Miller, A. H., Hepburn, K., … Waldrop-Valverde,D. (2019). Exercise and Cognitive Training as a Strategy to Improve Neurocognitive Outcomes in Heart Failure: a pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.211.

Zhao Q, Liu X, Wan X, Yu X, Cao X, Yang F, Cai Y. Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive impairment in older adults with heart failure: a systematic review. Geriatr Nurs 2023 May-Jun;51:378–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2023.04.008.

Gary RA, Paul S, Corwin E, Butts B, Miller AH, Hepburn K, Waldrop D. Exercise and cognitive training intervention improves Self-Care, Quality of Life and functional capacity in persons with heart failure. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(2):486–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820964338.

Zhou W, Zhang L, Wang T, Li Q, Jian W. Influence of social distancing on physical activity among the middle-aged to older population: evidence from the nationally representative survey in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:958189. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.958189.

Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:607–15.

Vaughan L, Corbin AL, Goveas JS. Depression and frailty in later life: a systematic review. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1947–58. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S69632.

Tsutsumimoto K, Doi T, Nakakubo S, Kim M, Kurita S, Ishii H, Shimada H. Cognitive Frailty as a risk factor for Incident Disability during Late Life: a 24-Month Follow-Up longitudinal study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(5):494–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1365-9.

Gramaglia C, Gattoni E, Marangon D, Concina D, Grossini E, Rinaldi C, Panella M, Zeppegno P. Non-pharmacological approaches to Depressed Elderly with no or mild cognitive impairment in Long-Term Care facilities. A systematic review of the literature. Front Public Health. 2021;9:685860. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.685860.

Thein FS, Li Y, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Wee SL, Ng TP. Physical frailty and cognitive impairment is associated with diabetes and adversely impact functional status and mortality. Postgrad Med. 2018;130(6):561–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00325481.2018.1491779.

Feinkohl I, Price JF, Strachan MWJ, Frier BM. The impact of diabetes on cognitive decline: potential vascular, metabolic, and psychosocial risk factors. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):46.

Barzilay JI, Blaum C, Moore T, Xue QL, Hirsch CH, Walston JD, et al. Insulin Resistance and inflammation as precursors of Frailty. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):635–41.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all the co-researchers, field workers, staff, local authorities, enumerators and participants for their involvement in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Long-term Research Grant Scheme (LGRS) provided by the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia (LRGS/1/2019/ UM-UKM/1/4, LRGS/BU/2012/UKM-UKM/K/01) and Grand Challenge Grant Project 1 and Project 2 (DCP-2017-002/1, DCP-2017-002/2) and Research University Grant (GUP-2018-066) funded by Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NFMR, DKAS, and SS contributed to the conception and design of the study. NFMR organized the database. NFMR and TCO performed the statistical analysis. NFMR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PS, RR, TCO, NFR, SS, and MZAK wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study has been approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM1.21.3/244/NN-2018-145) and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We verify that all procedures were conducted in compliance with applicable guidelines and regulations. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fatin Malek Rivan, N., Murukesu, R., Shahar, S. et al. Synergistic effects of cognitive frailty and comorbidities on disability: a community-based longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr 24, 448 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05057-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05057-3