Abstract

Background

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) involves a formal broad approach to assess frailty and creating a plan for management. However, the impact of CGA and its components on listing for kidney transplant in older adults has not been investigated.

Methods

We performed a single-center retrospective study of patients with end-stage renal disease who underwent CGA during kidney transplant candidacy evaluation between 2017 and 2021. All patients ≥ 65 years old and those under 65 with any team member concern for frailty were referred for CGA, which included measurements of healthcare utilization, comorbidities, social support, short physical performance battery, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Physical Frailty Phenotype (FPP), and estimate of surgical risk by the geriatrician.

Results

Two hundred and thirty patients underwent baseline CGA evaluation; 58.7% (135) had high CGA (“Excellent” or “Good” rating for transplant candidacy) and 41.3% (95) had low CGA ratings (“Borderline,” “Fair,” or “Poor”). High CGA rating (OR 8.46; p < 0.05), greater number of CGA visits (OR 4.93; p = 0.05), younger age (OR 0.88; p < 0.05), higher MoCA scores (OR 1.17; p < 0.05), and high physical activity (OR 4.41; p < 0.05) were all associated with listing on transplant waitlist.

Conclusions

The CGA is a useful, comprehensive tool to help select older adults for kidney transplantation. Further study is needed to better understand the predictive value of CGA in predicting post-operative outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

End-stage renal disease (ESRD) affects approximately 1,500 per million people in the United States, with increasing prevalence in patients aged 65 and older (50.4% as of 2019) [1, 2]. Kidney transplantation provides long-term benefits over dialysis, particularly survival, cost, and quality of life [3,4,5]. The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society (2012) recommend evaluating older adults prior to surgery across several domains, including assessment of cognitive ability and capacity, screening for depression, functional status, history of falls, baseline frailty score, nutritional status, medication history and polypharmacy, family and social support system, treatment goals and expectations, risk for delirium, screening of substance abuse and dependences.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome characterized by decreased physiological reserve and increased vulnerability for poor health outcomes [6]. Measuring frailty helps assess surgical risk for pre-operative transplant patients [7, 8], since higher degrees of frailty predict adverse outcomes following kidney transplantation [9]. However, there are over sixty validated frailty assessment tools and many programs do not regularly assess frailty using a validated tool [10, 11].

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) is a broad term that alludes to a formal assessment, typically in older adults, of frailty and various health needs in multiple domains (i.e., cognitive, physical, social, functional) that is summarized into a plan for management [12]. At our institution, CGAs measured healthcare utilization, comorbidities, social support, Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Physical Frailty Phenotype (PFP) in addition to modifiers of frailty (i.e., polypharmacy, dementia, disability, physical function, psychological health, polypharmacy, home service utilization, geriatric syndromes [13], and social, instrumental, and financial support) [14]. However, the impact of CGA and its components on the decision to list for kidney transplant in the older adult population has not been investigated. In this study, we determine the relationship between CGA and kidney transplant listing to provide a framework for comprehensively assessing risk associated with frailty during multidisciplinary discussion for kidney transplant listing.

Methods

Patient selection

A retrospective chart review of ESRD patients undergoing CGA during kidney transplant evaluation between 01/2017 and 07/2021 at the University of Chicago Medicine was performed (Fig. 1). Members of the transplant team referred all patients ≥ 65 years old or those under 65 with team member concern for presence of frailty or other geriatric syndromes to one geriatrician (M.M.) for CGA. Each CGA visit involved assessments of healthcare utilization, comorbidities, social support, SPPB, MoCA, PFP, and other validated tools relating to cognitive, physical, social, and functional domains of health (Supplemental Table S1). A decision support tool, [14] which was developed at our institution to standardize language involving estimate of risk from a geriatrics perspective, was utilized at each visit. At the end of each CGA visit, the geriatrician provided an overall CGA rating (ranging from “Excellent,” “Good,” “Borderline,” “Fair,” and “Poor”) of the patient’s candidacy for transplant. In our analysis, we grouped patients into those with a “high CGA rating” (overall CGA rating of “Excellent” or “Good”) and those with a “low CGA rating” (overall CGA rating of “Borderline,” “Fair,” or “Poor”) for comparison. The specifics of the CGA, as well as specific criteria used to determine CGA rating and clinician estimate of surgical risk are detailed in a previously published paper from our institution [14]. Abnormal findings during the CGA were managed on an individual basis, however, typical interventions are listed in Supplemental Table S2. Following CGA, patients were discussed in a multi-disciplinary meeting to decide if they should be listed for kidney transplant, deferred, or deemed ineligible for transplant. All members of the multi-disciplinary team were able to view results of the CGA evaluation. The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB21-1322).

A total of 29 patients did not have a final multi-disciplinary meeting (MDM) decision and were excluded from the study. The reasons for exclusion included: death before completion of pre-transplant evaluation by all specialists (n = 4), patient did not wish to complete pre-transplant evaluation (n = 3), currently ongoing further pre-transplant evaluation (n = 2), or patient was lost to follow-up (n = 20). No differences in CGA rating were noted in excluded patients.

Data Collection

Chart review was performed to collect patient characteristics, intraoperative course, postoperative outcomes, CGA domains, geriatrician’s assessment of patient risk, and final MDM decision. Patient zip codes were used to approximate median incomes (using 2006–2010 data published by the University of Michigan Population Studies Center) [15] and social vulnerability indices (using 2018 data from Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry) [16] of patients. Five factor modified frailty index (mFI-5) scores were calculated using data available in charts following previously published guidelines [17].

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and proportions; χ2 or Fischer’s Exact Test was used to calculate p-values between groups. Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations; an independent samples t-test was used to calculate p-values between groups. Binary logistic regression, which included clinically relevant variables and variables significant in univariate analysis, was used to calculate multivariable odds ratios (OR’s). Variables that crossed 0.5 in Pearson’s correlation coefficient with the outcome or were co-linear with other variables in the model were removed from the final multivariable logistic regression model. Breslow (generalized Wilcoxon) was used to determine difference in survival of patients following their latest CGA visit. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software (IBM SPSS statistics version 21).

Results

Characteristics of ESRD patients undergoing CGA and evaluation for kidney transplant

Table 1 shows characteristics of 230 patients who were evaluated. The mean and median follow-up times post-CGA were 13.6 and 10.5 months, respectively. A total of 135 patients (58.7%) had high CGA ratings for kidney transplant candidacy while 95 (41.3%) had low CGA ratings. Patients with high CGA ratings were older (69.3 ± 6.0 versus 67.4 ± 7.8) with higher average median income ($60,578 vs. $49,268), had lower rates of congestive heart failure, stroke, dementia, and coronary artery disease, but had a higher rate of peripheral vascular or arterial disease compared to patients with low CGA ratings (Table 1). Mean mFI-5 scores were higher in patients with low CGA ratings (Table 1). No differences were found between the two groups regarding sex, BMI, and social vulnerability index.

Relationship between CGA parameters, MDM decision, and overall CGA rating for kidney transplant candidacy

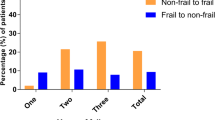

Table 2 shows the differences in CGA parameters among candidates with high versus low CGA ratings for kidney transplant candidacy. Patients with high CGA ratings were more likely to be independent (ADLs, iADLs), have a living will, not be on dialysis, have less polypharmacy, lower VES-13, lower PFP, lower PHQ-2, higher MoCA, and higher SPPB. Patients with low CGA ratings were more likely to have gait instability (two or more falls in last year and difficulty with balance), healthcare utilizations (at least one hospital admission, emergency room visit, or subacute rehab stay) in the last year, low physical activity, inadequate social support (as determined by geriatrician during visit), poorly controlled comorbidities, and an above average or higher geriatrician overall estimate of surgical risk. A total of 46 patients underwent transplantation (20%), with the majority (91.3%, 42/46) having high CGA ratings (Fig. 2). Four patients with low CGA ratings had improvements to their health status prior to being listed and subsequently transplanted (8.7%, 4/46).

Table 2 also shows the differences in CGA parameters among candidates listed versus not listed for kidney transplant by MDM decision. Compared to patients listed on the transplant waitlist, those not listed were more likely to have gait instability (2 or more falls in the last year and have difficulty with balance), a history of tobacco use, at least one hospital admission in the last year, low physical activity, poorly controlled comorbidities, and above average or greater surgical risk estimated by geriatrician. Patients listed were more likely to be independent (lower mean ADL assistance, and lower mean iADL dependency and assistance) and have lower VES-13, lower PFP, lower PHQ-2, and higher SPPB scores. All parameters showing a difference between listed versus not listed patients were considered for logistic regression in multivariable analysis (Table 3).

Multivariable analysis of CGA parameters predicting patient listing for kidney transplant

Multivariable logistic regression was performed after including CGA rating by geriatrician, number of CGA visits, age at CGA, MoCA score, history of tobacco use, high physical activity, control of comorbidities, and fall history in the model. CGA rating by geriatrician (OR 8.46 95% CI 1.37–52.40), number of CGA visits (OR 4.93 95% CI 1.61–15.11), age at CGA visit (treated as continuous variable; OR 0.88 95% CI 0.79–0.98), MoCA score (OR 1.17 95% CI 1.01–1.35), and high physical activity (OR 4.41 95% CI 1.09–17.78) were all significant predictors for listing for kidney transplant (Table 3).

Survival

Patients had mean and median follow-up times of 13.6 and 10.5 months following the CGA, respectively. In total, there were 22 deaths in the study (9.6%). A Breslow (generalized Wilcoxon) test showed that there was a difference in survival between patients with high versus low CGA ratings with those in the former group surviving longer (p = 0.038).

Discussion

Kidney transplantation for patients with ESRD can lead to improved quality of life and longevity relative to patients who remain on dialysis [18, 19]. There is significant variation in pre-operative assessment of older adults across various transplant centers [20]. Given the association of frailty with poor outcomes following kidney transplantation, [3, 7, 8, 19, 21] the CGA is a promising tool as it comprehensively assesses frailty through several validated metrics and fulfills many of the recommended items for pre-operative evaluation of older adults by the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society [22].

CGAs have existed for a few decades, and take more holistic approaches to evaluating the health of older adults, encompassing formal measurements of frailty and domains of health in addition to creating a plan for management [23]. To our knowledge, this is the first study assessing the impact of CGA on kidney transplant decision-making and listing in ESRD patients. Our study differs from other studies utilizing CGA in that the geriatrician used a clinical decision support tool to stratify candidates based on surgical risk (through classifying candidates as “Excellent,” “Good,” “Borderline,” “Fair,” or “Poor”) [23]. Although geriatrician recommendations could be simplified to “recommend” or “not recommend” (and in some cases, an intermediate zone), we believed a more granular approach with five categories was more appropriate given the comprehensive nature of the CGA. We found that the geriatrician’s CGA rating, the number of CGA appointments, age, MoCA score, and high physical activity were all significantly associated with MDM decision to list patients for kidney transplant in our multivariable logistic regression model. It should be noted that the geriatrician actively participated in the MDM and incorporated the results of the CGA into the decision-making process for listing. In addition, we found that several vulnerability domains (healthcare utilization, comorbidities, SPPB, social support, and PFP) differed among both patients listed versus not listed and patients given high CGA ratings versus low CGA ratings. The results of our study also show that patients with high CGA ratings had greater survival following their latest CGA. However, it should be noted that the mean follow-up time was only 13.6 months, and follow-up bias may have occurred given that patients had their CGA visits at different time points during the study period.

Although clinicians can use different frailty assessment tools to assess frailty in ESRD patients being evaluated for kidney transplant, there tends to be only moderate or fair agreement between them [24]. Haugen et al. showed that more frail patients, measured by PFP, are less likely to be placed on the transplant waitlist, [25] while Harhay et al. found that frail patients on the waitlist have higher mortality [26]. Despite frailty increasing risk for post-transplant adverse outcomes, transplantation in frail ESRD patients can improve quality of life [27]. Patients who are kidney transplant candidates have also expressed discomfort in clinical use of single constructs, such as frailty or cognitive scores, to deny potential candidates the ability to acquire a transplant [28]. Shrestha et al. surveyed expert clinicians who care for ESRD patients and found that they believed that frailty and cognitive scores should be evaluated in the context of other factors, such as frailty reversibility [29]. Whereas more concise measurements of frailty may focus on certain aspect of one’s health (i.e., cognitive and functional status or physical function), the CGA allows for the geriatrician to holistically evaluate a patient and make comprehensive recommendations to manage aspects of frailty and health that would establish surgical risk, inform eligibility, implement pre-operative interventions that may help reduce surgical risk and frailty and prepare for peri- and post-operative care. Although there is controversy regarding the reversibility of frailty, aspects of frailty (such as physical frailty) may be managed through methods such as adequate protein-calorie consumption, exercise, or reduction of polypharmacy [21]. In our study, we found that more CGA visits were associated with a greater likelihood of transplantation. Generally, patients who had absolute contraindications (i.e., history of renal cell carcinoma or significant calcification of vasculature) did not have a path back for transplant reevaluation. However, if the reason for not listing was related to a modifiable risk factor (i.e., high BMI or poor physical function), patients were provided recommendations prior to a repeat CGA the following year. Patients who were listed or were borderline candidates for transplant (usually with deferred waitlist decision) were seen annually for follow-up visits. Repeated assessments at multiple time points is a strength of the CGA as it allows for monitoring of improvements of health status and optimization of outcomes in patients who are borderline candidates for transplantation. It should be noted that patients at the time of their first CGA visit had variable amounts of time on dialysis and that chronic dialysis can affect one’s physical function (e.g., cardiovascular health), and in turn, frailty [30].

Though the CGA allows for a more multidimensional evaluation of older adults, it comes with a few drawbacks. Firstly, it is time- and resource-intensive given the multiple assessments that are involved. Secondly, not all hospital systems may have the resources and facilities to perform CGAs. However, with an aging population and shift of burden of disease from acute to chronic in the United States, a more holistic evaluation of frailty and key measures of health is important for equitable selection of transplant candidates.

Conclusion

Our study is a single-center retrospective observational study which demonstrated the association of CGA with kidney transplant listing. All 230 patients were seen by the same geriatrician, but multiple transplant clinicians were involved in the final MDM decision to list. A prospective trial with a larger cohort of patients and longitudinal follow-up may shed light on how CGA may predict post-transplant outcomes and how serial CGAs could help manage frailty and improve chances for kidney transplant listing.

Limitations

Our study was limited by its retrospective nature and short follow up. Although CGA ratings were based on a published standardized decision support tool, a sole geriatrician performed all the CGAs in the study, which may have had single evaluator bias. At our institution, we do not have a defined, objective criteria to refer patients for pre-operative kidney transplant evaluation in patients under the age of 65. In the study, five patients were under 50 and 48 were under 65. In addition, our survival analysis had follow-up bias since patients had their CGA visits at different points.

Data availability

Although collected patient data was de-identified prior to analysis, data sharing is not available as the risk for breaches of confidentiality must be minimized by limiting data access. A request for data should be sent to the corresponding author (JP).

Abbreviations

- CGA:

-

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

- ESRD:

-

End-Stage Renal Disease

- ADL:

-

Activities of Daily Living

- iADL:

-

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- VES-13:

-

Vulnerable Elders Survey 13

- PFP:

-

Physical Frailty Phenotype

- SPPB:

-

Short Physical Performance Battery

- mFI-5:

-

Five Factor Modified Frailty Index

- MDM:

-

Multi-Disciplinary Meeting

References

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, Boyarsky B, Gimenez L, Jaar BG, Walston JD, Segev DL. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901.

System USRD. 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. In. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD.

Jay CL, Washburn K, Dean PG, Helmick RA, Pugh JA, Stegall MD. Survival Benefit in older patients Associated with earlier transplant with high KDPI kidneys. Transplantation. 2017;101(4):867–72.

Knoll GA. Kidney transplantation in the older adult. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(5):790–7.

Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, Jadhav D, Klarenbach S, Gill J. Systematic review: kidney transplantation compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(10):2093–109.

Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:433–41.

Nastasi AJ, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Schrack J, Ying H, Olorundare I, Warsame F, Mountford A, Haugen CE, González Fernández M, Norman SP, et al. Pre-kidney Transplant Lower Extremity Impairment and Post-kidney Transplant Mortality. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(1):189–96.

Thomas AG, Ruck JM, Shaffer AA, Haugen CE, Ying H, Warsame F, Chu N, Carlson MC, Gross AL, Norman SP, et al. Kidney transplant outcomes in recipients with cognitive impairment: a National Registry and prospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2019;103(7):1504–13.

Harhay MN, Rao MK, Woodside KJ, Johansen KL, Lentine KL, Tullius SG, Parsons RF, Alhamad T, Berger J, Cheng XS. An overview of frailty in kidney transplantation: measurement, management and future considerations. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. 2020;35(7):1099–112.

Kao J, Reid N, Hubbard RE, Homes R, Hanjani LS, Pearson E, Logan B, King S, Fox S, Gordon EH. Frailty and solid-organ transplant candidates: a sco** review. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):864.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Chu NM, Agoons D, Parsons RF, Alhamad T, Johansen KL, Tullius SG, Lynch R, Harhay MN, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding Frailty in kidney transplantation: results of a National Survey. Transplantation. 2020;104(2):349–56.

Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, McCleod A, Arora S, Nockels K, Kennedy S, Roberts H, Conroy S. What is comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing. 2018;47(1):149–55.

Flacker JM. What is a geriatric syndrome anyway? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):574–6.

Huisingh-Scheetz M, Martinchek M, Becker Y, Ferguson MK, Thompson K. Translating frailty research into clinical practice: insights from the successful aging and frailty evaluation clinic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(6):672–8.

Zip Code Characteristics.: Mean and Median Household Income [https://www.psc.isr.umich.edu/dis/census/Features/tract2zip/].

SVI Interactive Map. [https://svi.cdc.gov/map.html].

Subramaniam S, Aalberg JJ, Soriano RP, Divino CM. New 5-Factor modified Frailty Index using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(2):173–181e178.

KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Hemodialysis Adequacy. 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884–930.

Rao PS, Merion RM, Ashby VB, Port FK, Wolfe RA, Kayler LK. Renal transplantation in elderly patients older than 70 years of age: results from the Scientific Registry of Transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2007;83(8):1069–74.

Mandelbrot DA, Fleishman A, Rodrigue JR, Norman SP, Samaniego M. Practices in the evaluation of potential kidney transplant recipients who are elderly: a survey of US transplant centers. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(10):e13088.

Morley JE, Vellas B, Van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea W, Doehner W, Evans J. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7.

Chow W, Rosenthal R, Merkow R, Ko C, Esnaola N, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; American Geriatrics Society. Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(4):453–66.

Lee H, Lee E, Jang I-Y. Frailty and comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Korean Med Sci 2020, 35(3).

Worthen G, Vinson A, Cardinal H, Doucette S, Gogan N, Gunaratnam L, Keough-Ryan T, Kiberd BA, Prasad B, Rockwood K, et al. Prevalence of Frailty in patients referred to the kidney transplant Waitlist. Kidney360. 2021;2(8):1287–95.

Haugen CE, Chu NM, Ying H, Warsame F, Holscher CM, Desai NM, Jones MR, Norman SP, Brennan DC, Garonzik-Wang J, et al. Frailty and Access to kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):576–82.

Harhay MN, Rao MK, Woodside KJ, Johansen KL, Lentine KL, Tullius SG, Parsons RF, Alhamad T, Berger J, Cheng XS, et al. An overview of frailty in kidney transplantation: measurement, management and future considerations. Nephrol Dialysis Transplantation. 2020;35(7):1099–112.

Wu HHL, Woywodt A, Nixon AC. Frailty and the potential kidney transplant recipient: time for a more holistic Assessment? Kidney360. 2020;1(7):685–90.

Shrestha P, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Fazal M, Chu NM, Garonzik-Wang JM, Gordon EJ, McAdams-DeMarco M, Humbyrd CJ. Patient perspectives on the Use of Frailty, cognitive function, and age in kidney transplant evaluation. AJOB Empir Bioeth 2022:1–12.

Shrestha P, Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, King EA, Gordon EJ, Faden RR, Segev DL, Humbyrd CJ, McAdams-DeMarco M. Defining the ethical considerations surrounding kidney transplantation for frail and cognitively impaired patients: a Delphi study of geriatric transplant experts. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):566.

McIntyre CW. Effects of hemodialysis on cardiac function. Kidney Int. 2009;76(4):371–5.

Acknowledgements

N/A.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: MLM. Acquisition of data: JP. Data analysis and interpretation: All authors. Drafting and substantial revision of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB: IRB21-1322). Given the retrospective nature of the study and nature of disease course (mortality in ESRD), the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board waived the informed consent requirement for this study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in order to minimize the risk of breach of confidentiality.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, J., Martinchek, M., Mills, D. et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts listing for kidney transplant in patients with end-stage renal disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 24, 148 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04734-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04734-7