Abstract

Background

Previous studies have suggested that certain personal psychological variables (e.g., life satisfaction and cognitive function) and physical variables (e.g., body mass index [BMI]) are significantly associated with individuals’ anxiety symptoms. However, relevant research on elderly is lagging and no studies have yet investigated the combined impact of these variables on anxiety. Thus, we conducted the present study to investigate the potential moderator role of BMI and the potential mediator role of cognitive function underlying the relationship between life satisfaction and anxiety symptoms in Chinese elderly based in Hong Kong.

Methods

Sixty-seven elderly aged 65 years old and above were recruited from the local elderly community centres in this pilot study. Each participant underwent a systematic evaluation using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Hong Kong Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA), and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) and were measured for their body weight and height. Regression analysis using the bootstrap** method was employed to test the hypothesized moderated mediation model.

Results

Our findings demonstrated the overall model accounted for 23.05% of the variance in scores of HAM-A (F (8, 57) = 2.134, p = 0.047) in Chinese elderly. There was a significant association between life satisfaction and anxiety symptoms (p = 0.031), indicating that individuals with higher life satisfaction were associated with less anxiety symptoms. Moreover, this relationship was positively moderated by BMI (b = 0.066, 95% CI [0.004, 0.128]), especially in Chinese elderly with BMI at a lower level (b = -0.571, 95% CI [-0.919, -0.224]) and an average level (b = -0.242, 95% CI [-0.460, -0.023]). No significant mediator role was detected for cognitive function (b = -0.006, 95% CI [-0.047, 0.044]) in our model.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that increased life satisfaction can reduce anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly as their BMI decreases (when BMI ranged between “mean - 1SD” and “mean” of the population). The significant interaction between psychological and physical factors underlying anxiety symptoms found in this study, presents a promising opportunity for translation into multi-level psychological and physical interventions for the management of anxiety in ageing patients during clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anxiety is an unpleasant emotion (e.g., a feeling of fear or worry about an anticipated event) accompanied by somatic complaints. It is a common mental health problem. According to epidemiological data from Western countries, the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorder ranges from 14.5% to 33.7% in the general population [1,2,3]. Although anxiety disorder is a widespread mental health concern, its prevalence among elderly has only attracted more scientific interest in recent decades. In the community-dwelling elderly, it has been reported that the prevalence of anxiety disorder varies from 1.2% to 17.2% [4,5,6], while the estimated prevalence for elderly in clinical settings is higher at 28% [7]. Differing from clinical diagnosed anxiety disorder, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms that do not satisfy the criteria for clinically diagnosed anxiety disorder is estimated to be 15.0%–56.0% in elderly [7]. A national survey of the general population in China revealed a lifetime prevalence for anxiety disorder of 7.6% [8]. For Chinese elderly, the prevalence of anxiety disorder is 3.71%, according to a recent study conducted by Xu et al. [9]. A review of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms among more specific populations of Chinese elderly showed a prevalence of 7.9%–20.8% for those dwelling in communities [10,34]. Furthermore, there is an accumulation of evidence showing the contribution of an unfavourable BMI to the development of anxiety and other mental health problems, e.g., mood and alcohol disorders [35]. Leonore et al. conducted a longitudinal cohort study in the Netherlands and found that obese individuals have an increased risk of develo** anxiety [36]. In this prospective study which included 5303 participants, compared to individual with normal BMI, obese individual at baseline were found to have a significantly higher risk of onset of anxiety disorder during follow-up (odds ratio = 1.71). The positive association between unfavourable BMI and anxiety was further confirmed by a systematic review and meta-analysis. In this study, Gariepy et al. included 16 studies (2 prospective studies and 14 cross-sectional studies) and revealed a pooled odds ratio of 1.4 (with 95% confidence interval of 1.20–1.60) for association between obesity and anxiety disorder [37]. Consistently, in another systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Amiri et al., findings indicated a pooled odds ratio of 1.1 (with 95% confidence interval of 1.20–1.41) for anxiety symptoms in overweight individuals, and a pooled odds ratio of 1.3 (with 95% confidence interval of 1.00–1.21) for anxiety symptoms in obese individuals [38]. Interestingly, in a study based on data from 103,557 individuals aged 18–85 years old in the United States, a U-shaped association was demonstrated, suggesting that individuals who are either underweight or overweight have higher risks of develo** anxiety than individuals with normal BMI [39]. However, the majority of studies investigating the impact of BMI on anxiety have been carried out in Western countries and studies of Chinese and in particular, older Chinese adult populations, remain scarce.

The psychological variables, SWL and cognitive function, and the physical variable, BMI, have been reported to be associated with anxiety, but relevant research in elderly is lagging and no studies have yet investigated the combined impact of these variables on anxiety symptoms at subclinical levels. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of SWL on anxiety symptoms in Chinese elderly based in Hong Kong. We speculated a potential moderator role of BMI and a potential mediator role of cognitive function underlying the relationship between SWL and anxiety symptoms. We hypothesized that among older adults in Hong Kong: 1) SWL is negatively associated with anxiety symptoms; 2) the negative association between SWL and anxiety symptoms is moderated by BMI; 3) the negative association between SWL and anxiety symptoms is partially mediated by the cognitive function of elderly.

Methods

Participants

In this cross-sectional cohort study, participants were recruited from local communities, e.g., Neighbourhood Elderly Centre in Hong Kong. Participants were included if they were: (1) aged 65 years old or above; (2) able to speak Cantonese; and (3) ambulatory. Participants were excluded if they: (1) had uncorrected visual or auditory impairment; (2) were unable to follow assessment instructions from the research personnel; or (3) had any non-psychiatric chronic medical conditions (e.g., chronic kidney disease, or diabetes). The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institutional Review Board approved the present study. Sample size calculation was conducted using G*power for a multiple regression analysis [40] as in a previous study [41]. The parameters for power analysis were set as: f2 = 0.15 (medium effect size), a power of 0.80, and an α = 0.05. A minimum of 55 participants were required to detect the medium effect size for the proposed 4 variables with 80% power.

Procedures

Prior to the study, a research package with an information sheet and consent form were given to each participant. The research personnel explained the objectives and procedures of the study to each participant and obtained their written informed consent. Each participant was then requested to provide demographic information, including their age, gender, education, and medical history, in addition to their body weight and height measurements. Subsequently, each participant was tested for their intelligence level using the Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, Fourth Edition (TONI-4). Finally, life satisfaction, cognitive function, and anxiety symptoms, were systematically evaluated using the respective instruments: the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), Hong Kong Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA), and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A). All assessments were performed through face-to-face conversations between the participants and the research personnel, with frequent rest periods offered to avoid mental fatigue.

Instruments

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

The SWLS was employed to evaluate participants’ subjective feelings of life satisfaction [42]. It is a five-item survey with a 7-point Likert response scale (from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’). Total scores for the SWLS range from 5 to 35, with lower scores indicating more dissatisfaction with life and higher scores indicating more satisfaction with life [43]. The test–retest reliability of the SWLS have been confirmed by others (test–retest correlation coefficient = 0.85), which demonstrates that it is suitable to be used in the elderly and is reliable in determining affect status [44]. The Chinese version of SWLS has consistently shown high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91), and has been widely used [45].

Hong Kong version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA)

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is a widely used assessment tool for cognitive function in older individuals. It consists of seven components including 1) Attention/Concentration, 2) Naming, 3) Executive/Visuospatial Function, 4) Language, 5) Delayed Recall, 6) Orientation, and 7) Abstract Reasoning. Previous studies have shown that the assessment has good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.83) and test–retest reliability (test–retest correlation coefficient = 0.92) [46]. The HK-MoCA has been translated from English to Cantonese with appropriate cultural and linguistic modifications [53]. This analysis involves a nonparametric procedure that produces a confidence interval (CI) by integrating the Syntax programme in SPSS. The potential moderating effect of BMI and the potential mediating effect of cognitive function were evaluated using PROCESS macro programme Model 5, based on 10,000 bootstrap** resampling events after adjustment for age, gender, education level, and TONI-4 index score. All continuous variables included in the model were mean centred. For the moderated mediation analysis, if zero wasn’t included in the calculated CI, the moderating effect or the mediating effect was considered to be significant. For the rest of the data analyses, p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Participants’ demographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, total 67 elderly with a mean age of 70.96 ± 5.04, were recruited in the present study, including 56 females (83.6%) and 11 males (16.4%). Of these 67 elderlies, 10.4% had an educational attainment below primary school and 89.6% had an educational attainment of primary school or higher. The mean BMI of the participants was 23.72 ± 5.05 kg/m2. The mean TONI-4 index, SWLS, HK-MoCA, and HAM-A scores were, 100.25 ± 10.33, 27.00 ± 5.40, 25.21 ± 3.59, and 6.09 ± 4.81, respectively.

Pearson’s correlation analysis

Table 2 shows the Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the variables of interest. The results show that SWLS scores were negatively correlated with HAM-A scores (r = -0.338, p = 0.005), indicating that a higher level of life satisfaction was associated with less anxiety symptoms in the study population (Table 2).

Moderated mediation analysis

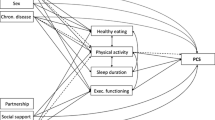

Consistent with the findings of the Pearson’s correlation analysis, SWLS scores remained significantly associated with HAM-A scores after adjustment for age, gender, education level, and TONI-4 index score (b = -0.242, p = 0.031). There was no significant association between HK-MoCA scores and HAM-A scores after adjustment for age, gender, education level, and TONI-4 index score. No significant association was identified between BMI and HAM-A scores (Fig. 1). However, when taken as a set, the proposed moderated mediation model accounted for 23.05% of the variance in HAM-A scores (F (8, 57) = 2.134, p = 0.047). Moreover, we found a significant interaction between SWLS scores and BMI (F (1, 57) = 4.525, p = 0.038) among Chinese elderly. A significant conditional direct effect of SWLS scores on HAM-A scores was identified at different levels of BMI (presented as the mean – 1 SD, mean, and mean + 1 SD; Table 3). The direct effect of life satisfaction on symptoms of anxiety was significant for Chinese elderly with a lower level of BMI (mean – 1 SD; b = -0.571, 95% CI [-0.919, -0.224]) and an average level of BMI (mean; b = -0.242, 95% CI [-0.460, -0.023]), which indicates stronger association between life satisfaction and symptoms of anxiety as BMI value decreases (Fig. 2). Whereas for elderly with higher level of BMI (mean + 1 SD), the direct effect of life satisfaction on the symptoms of anxiety was not significant (b = 0.088, 95% CI [-0.321, 0.497]). Subsequent John–Neyman analysis showed that the impact of life satisfaction on the symptoms of anxiety was significantly moderated by BMI, until a value of 24.12 kg/m2 (p = 0.05; 95% CI [-0.445, 0.000]; Table 4). No significant indirect mediating effect was detected for cognitive function, as proposed in our model (b = -0.006, 95% CI [-0.047, 0.044]).

The moderated mediation model for life satisfaction on symptoms of anxiety in Chinese elderly

Significances were found for the direct effect of life satisfaction on symptoms of anxiety (p = 0.031) (path c) and moderating effect of BMI (p = 0.038) (path d) after adjustment for age, gender, education level, and TONI-4 index scores. However, no significant indirect effect was detected for cognitive function as proposed in our model (b = -0.006, 95% CI [-0.047, 0.044]) (path a*b). The overall moderated mediation model accounting for 23.05% of the variance in scores of HAM-A (F (8, 57) = 2.134, p = 0.047). *Significant at p < 0.05

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the association between SWL and anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly and its potential underlying mechanisms. Our findings showed that SWL was negatively associated with anxiety symptoms (Hypothesis 1), and this effect was moderated by BMI (Hypothesis 2). However, cognitive function was not a mediator of the relationship between SWL and anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly as revealed by the present study (Hypothesis 3).

Consistent with previous findings [19, 21,22,23,24], we found that a higher SWL was associated with less severe symptoms of anxiety among Chinese elderly. SWL, which reflects a positive life perception, has been suggested to play an important role in maintaining subjective well-being [54]. Subjective well-being, which is conceptualised as positive psychology, is a recently established discipline that emphasises taking a positive perspective on things [55]. It has been suggested that positive affect and cognitive processes are powerful protective factors against worry and can buffer dysfunctional stress and thoughts that may lead to anxiety [56,57,58]. Conversely, dissatisfaction with life, which reflects negative perceptions of life, has been documented to predict anxiety across an individual’s lifespan [59]. In later adulthood, individuals are often faced with unfavourable life changes related to decreased life satisfaction, such as fewer social connections, the loss of partners, and financial dependence. These adverse life changes may result in feelings of loneliness, helplessness, and uselessness, which lead to negative thoughts and affect. Without appropriate interventions, negative life perception, accompanied by chronic worry and stress, may gradually cause anxiety symptoms in older adults. The current evidence supporting the protective role of higher SWL against anxiety symptoms in Chinese elderly has important clinical implications and the potential for being translated into an intervention using positive psychology. Psychological interventions focusing on the positive side of things increase perceptions of pleasure, satisfaction, and well-being, and have demonstrated significant clinical effectiveness. In a recent meta-analysis, Chakhssi et al. demonstrated a moderate effect size for utilising positive psychology to induce anxiety remission [60]. In light of all of the above evidence, it is time to promote an appropriate positive psychology programme to increase life satisfaction to prevent anxiety symptoms in Chinese elderly.

Additionally, our findings have shown that the neuroprotective effect of SWL on anxiety symptoms is moderated by BMI (a physical factor). For Chinese elderly with lower and average levels of BMI, a higher SWL had a protective effect on anxiety symptoms, whereas, for those with a higher level of BMI, the significant impact of SWL on anxiety symptoms disappeared. The cut-off for a higher level of BMI in the present study was 24.12 kg/m2 (Table 4), which approximately represents overweight and obesity. It has been suggested that individuals with an elevated BMI, particularly those with obesity, have elevated concentrations of serum inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin 6 (IL-6) [61]. Likewise, individuals diagnosed with anxiety disorders also present with increased concentrations of inflammatory markers [62]. Given that adverse life changes in later adulthood cause chronic worry and stress, which lead to an increased inflammatory response (due to the dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis) [63], it is speculated that a higher SWL can decrease anxiety symptoms in the elderly by reducing inflammation through the suppression of an overactive immune system. Therefore, among elderly with a higher level of BMI, the neuroprotective effect of SWL is counteracted by the abnormal inflammatory response associated with obesity and the coexisting high dietary fat intake. This would negate the neuroprotective effect of SWL on anxiety symptoms in Chinese elderly with a higher BMI. However, in Chinese elderly with lower and average levels of BMI, BMI is discovered to facilitate less anxiety symptoms which may be partially due to the synergistic effects of both SWL and BMI on immune response regulation. While, these assumptions need to be investigated in future studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study highlighting the moderator role of BMI in the association between SWL and anxiety symptoms. In addition to promoting a positive psychology programme, the interaction between psychological and physical factors influencing anxiety symptoms revealed in this study, suggests a multi-level intervention model for Chinese elderly during clinical practice. The multi-level model should include physical interventions with nutritional counselling and regular exercise to achieve physical fitness and to avoid overweight and obesity [64]. It should also include a psychological intervention using positive psychology to achieve subjective well-being.

In contrast to previous studies, we did not find any association between cognitive function and anxiety symptoms at subclinical levels in Chinese elderly. One reason for non-significant result may be due to the limited sample size which lacked statistical power to detect a significant effect. Another reason may be due to the cognitive instrument used in the present study which may not be sensitive enough to reflect the precise cognitive process. For example, in the study by Gulpers et al., the individual’s capabilities for attention, verbal memory, executive function, and information processing speed were measured using the Concept Shifting Test, the Visual Verbal Word Leaning Test, the Stroop Color Word Test, and the Letter Digit Substitution Test, respectively [29]. Although the HK-MoCA sufficiently evaluates global cognitive function and screens individuals with mild cognitive impairment, it has limitations in the accurate assessment of different cognitive domains. Recently, Feng et al. reported that worry caused by adverse life events is maintained and strengthened by an individual’s deficiencies in attention and interpretational memory (cognitive function), which can predict anxiety symptoms in the general population [56]. In contrast to this, we did not identify a mediating effect of cognitive function in the association between SWL and anxiety symptoms, which needs to be further investigated using more specific cognitive instruments in future studies.

There are several limitations of the present study. First, our findings cannot suggest a causal relationship because of the cross-sectional study design, although a strong association between SWL and anxiety symptoms and a significant moderating effect of BMI were identified in Chinese elderly. Future research in this area is recommended to verify our findings using a prospective longitudinal study design. Second, we used self-reported questionnaires to measure anxiety symptoms, which may yield responses affected by an individual’s honesty, memory, and social context. These factors can lead to incorrect or inaccurate responses, and subsequently increase the bias in our findings. Future research is recommended to supplement the present subjective questionnaires using objective structured clinical interviews, as the combined data collection approaches will avoid potential errors and provide more comprehensive information. Third, more specific cognitive instruments specifically measuring different cognitive domains should be used in future studies, instead of the general cognitive performance test used in the present study. Other cognitive factors, such as interpretation bias (i.e., interpretation of ambiguous situations in a negative way) should also be measured in future studies to better understand the underlying neuropathological mechanisms of the association between SWL and anxiety symptoms at subclinical levels. Fourth, this pilot study was only based in Hong Kong, a modern city in Southern China. Considering the economic level, living conditions, and cultural differences between Southern and Northern China, findings in this study cannot be representative of the overall elderly population in China. Future research should expand the present study by collecting samples of multiple provinces/cities of China to generalize the findings for a larger population of Chinese elderly.

In the present pilot study, we constructed a moderated mediation model to investigate the linking pathway between SWL and anxiety symptoms in a subclinical ageing population. The subclinical population has been found to share risk factors as well as underlying neuropathological mechanisms related with clinical diagnosed anxiety. For the first time, we demonstrated the moderating effect of BMI underpinning the association between SWL and anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly in Hong Kong. Our findings show that life satisfaction could reduce anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly as their BMI decreases (when BMI ranged between “mean-1SD” and “mean” of the population). The significant interaction between psychological and physical variables shown in the present study will be translated to promote multi-level psychological and physical interventions for ageing patients with anxiety during clinical practice.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- TONI-4:

-

Test of Nonverbal Intelligence, Fourth Edition

- SWLS:

-

Satisfaction with Life Scale

- HK-MoCA:

-

Hong Kong Version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- HAM:

-

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

References

Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen HU. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169–84.

Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) experience. J Psychiatr Res. 1990;24(Suppl 2):3–14.

Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, Bryson H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;420:21–7.

Welzel FD, Stein J, Rohr S, Fuchs A, Pentzek M, Mosch E, et al. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and their association with loss experience in a large cohort sample of the oldest-old. Results of the AgeCoDe/AgeQualiDe study. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:285.

Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Castriotta N, Lenze EJ, Stanley MA, Craske MG. Anxiety disorders in older adults: a comprehensive review. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(2):190–211.

Kirmizioglu Y, Dogan O, Kugu N, Akyuz G. Prevalence of anxiety disorders among elderly people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(9):1026–33.

Bryant C, Jackson H, Ames D. Depression and anxiety in medically unwell older adults: prevalence and short-term course. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(4):754–63.

Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, Liu Z, Yu X, Yan J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):211–24.

Xu G, Chen G, Zhou Q, Li N, Zheng X. Prevalence of mental disorders among older Chinese People in Tian** City. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(11):778–86.

Ding KR, Wang SB, Xu WQ, Lin LH, Liao DD, Chen HB, et al. Low mental health literacy and its association with depression, anxiety and poor sleep quality in Chinese elderly. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2022;14(4):e12520.

Zhao W, Zhang Y, Liu X, Yue J, Hou L, **a X, et al. Comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms and frailty among older adults: findings from the West China health and aging trend study. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:970–6.

Liu Y, Xu Y, Yang X, Miao G, Wu Y, Yang S. The prevalence of anxiety and its key influencing factors among the elderly in China. Front Psych. 2023;14:1038049.

**e Q, Xu YM, Zhong BL. Anxiety symptoms in older Chinese adults in primary care settings: prevalence and correlates. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1009226.

Becker E, Orellana Rios CL, Lahmann C, Rucker G, Bauer J, Boeker M. Anxiety as a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;213(5):654–60.

Allgulander C. Anxiety as a risk factor in cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(1):13–7.

Ribeiro O, Teixeira L, Araujo L, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Calderon-Larranaga A, Forjaz MJ. Anxiety, Depression and quality of life in older adults: trajectories of influence across age. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):9039.

Hellwig S, Domschke K. Anxiety in late life: an update on pathomechanisms. Gerontology. 2019;65(5):465–73.

Schutz E, Sailer U, Al Nima A, Rosenberg P, AnderssonArnten AC, Archer T, et al. The affective profiles in the USA: happiness, depression, life satisfaction, and happiness-increasing strategies. PeerJ. 2013;1:e156.

Fergusson DM, McLeod GF, Horwood LJ, Swain NR, Chapple S, Poulton R. Life satisfaction and mental health problems (18 to 35 years). Psychol Med. 2015;45(11):2427–36.

Rissanen T, Viinamaki H, Honkalampi K, Lehto SM, Hintikka J, Saharinen T, et al. Long term life dissatisfaction and subsequent major depressive disorder and poor mental health. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:140.

Bray I, Gunnell D. Suicide rates, life satisfaction and happiness as markers for population mental health. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(5):333–7.

Lombardo P, Jones W, Wang L, Shen X, Goldner EM. The fundamental association between mental health and life satisfaction: results from successive waves of a Canadian national survey. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):342.

Hoseini-Esfidarjani SS, Tanha K, Negarandeh R. Satisfaction with life, depression, anxiety, and stress among adolescent girls in Tehran: a cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):109.

Ooi PB, Khor KS, Tan CC, Ong DLT. Depression, anxiety, stress, and satisfaction with life: moderating role of interpersonal needs among university students. Front Public Health. 2022;10:958884.

Seo EH, Kim SG, Kim SH, Kim JH, Park JH, Yoon HJ. Life satisfaction and happiness associated with depressive symptoms among university students: a cross-sectional study in Korea. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2018;17:52.

Mantella RC, Butters MA, Dew MA, Mulsant BH, Begley AE, Tracey B, et al. Cognitive impairment in late-life generalized anxiety disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(8):673–9.

Butters MA, Bhalla RK, Andreescu C, Wetherell JL, Mantella R, Begley AE, et al. Changes in neuropsychological functioning following treatment for late-life generalised anxiety disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(3):211–8.

Unterrainer JM, Domschke K, Rahm B, Wiltink J, Schulz A, Pfeiffer N, et al. Subclinical levels of anxiety but not depression are associated with planning performance in a large population-based sample. Psychol Med. 2018;48(1):168–74.

Gulpers BJA, Verhey FRJ, Eussen S, Schram MT, de Galan BE, van Boxtel MPJ, et al. Anxiety and cognitive functioning in the Maastricht study: a cross-sectional population study. J Affect Disord. 2022;319:570–9.

Potvin O, Forget H, Grenier S, Preville M, Hudon C. Anxiety, depression, and 1-year incident cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1421–8.

Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R. Late-life anxiety and cognitive impairment: a review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(10):790–803.

Nuttall FQ. Body mass index: obesity, BMI, and health: a critical review. Nutr Today. 2015;50(3):117–28.

Williams EP, Mesidor M, Winters K, Dubbert PM, Wyatt SB. Overweight and obesity: prevalence, consequences, and causes of a growing public health problem. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(3):363–70.

Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, Spadano JL, Laird N, Dietz WH, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of develo** common chronic diseases during a 10-year period. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(13):1581–6.

Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Vilagut G, Martinez M, Bonnewyn A, De Graaf R, et al. The relation between body mass index, mental health, and functional disability: a European population perspective. Can J Psychiatr Rev. 2008;53(10):679–88.

de Wit L, Have MT, Cuijpers P, de Graaf R. Body Mass Index and risk for onset of mood and anxiety disorders in the general population: results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2 (NEMESIS-2). BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):522.

Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes. 2010;34(3):407–19.

Amiri S, Behnezhad S. Obesity and anxiety symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr. 2019;33(2):72–89.

DeJesus RS, Breitkopf CR, Ebbert JO, Rutten LJ, Jacobson RM, Jacobson DJ, et al. Associations between anxiety disorder diagnoses and body mass index differ by age, sex and race: a population based study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Mental Health. 2016;12:67–74.

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–91.

Xu X, Chen L, Yuan Y, Xu M, Tian X, Lu F, et al. Perceived Stress and Life satisfaction among Chinese clinical nursing teachers: a moderated mediation model of burnout and emotion regulation. Front Psych. 2021;12:548339.

Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5.

Pavot W, Diener E. Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychol Assess. 1993;5(2):164–72.

Pavot W, Diener E, Colvin CR, Sandvik E. Further validation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. J Pers Assess. 1991;57(1):149–61.

Tian HM, Wang P. The role of perceived social support and depressive symptoms in the relationship between forgiveness and life satisfaction among older people. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(6):1042–8.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Wong A, **ong YY, Kwan PW, Chan AY, Lam WW, Wang K, et al. The validity, reliability and clinical utility of the Hong Kong Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA) in patients with cerebral small vessel disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28(1):81–7.

Yeung PY, Wong LL, Chan CC, Leung JL, Yung CY. A validation study of the Hong Kong version of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (HK-MoCA) in Chinese older adults in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2014;20(6):504–10.

Zimmerman M, Martin J, Clark H, McGonigal P, Harris L, Holst CG. Measuring anxiety in depressed patients: a comparison of the Hamilton anxiety rating scale and the DSM-5 Anxious Distress Specifier Interview. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;93:59–63.

Wang J, Zhu E, Ai P, Liu J, Chen Z, Wang F, et al. The potency of psychiatric questionnaires to distinguish major mental disorders in Chinese outpatients. Front Psych. 2022;13:1091798.

Chen KW, Lee YC, Yu TY, Cheng LJ, Chao CY, Hsieh CL. Test-retest reliability and convergent validity of the test of nonverbal intelligence-fourth edition in patients with schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):39.

Mungkhetklang C, Crewther SG, Bavin EL, Goharpey N, Parsons C. Comparison of measures of ability in adolescents with intellectual disability. Front Psychol. 2016;7:683.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91.

Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1984;95(3):542–75.

A psychology of satisfaction. Proponents of positive psychology want to find out what makes us happy. Harv Womens Health Watch. 2005;13(2):4–5.

Feng YC, Krahe C, Koster EHW, Lau JYF, Hirsch CR. Cognitive processes predict worry and anxiety under different stressful situations. Behav Res Ther. 2022;157:104168.

Taylor CT, Tsai TC, Smith TR. Examining the link between positive affectivity and anxiety reactivity to social stress in individuals with and without social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;74:102264.

Folkman S, Moskowitz JT. Positive affect and the other side of co**. Am Psychol. 2000;55(6):647–54.

Beutel ME, Glaesmer H, Wiltink J, Marian H, Brahler E. Life satisfaction, anxiety, depression and resilience across the life span of men. Aging Male. 2010;13(1):32–9.

Chakhssi F, Kraiss JT, Sommers-Spijkerman M, Bohlmeijer ET. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):211.

Fulton S, Decarie-Spain L, Fioramonti X, Guiard B, Nakajima S. The menace of obesity to depression and anxiety prevalence. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33(1):18–35.

Michopoulos V, Powers A, Gillespie CF, Ressler KJ, Jovanovic T. Inflammation in fear- and anxiety-based disorders: PTSD, GAD, and Beyond. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(1):254–70.

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Doyle WJ, Miller GE, Frank E, Rabin BS, et al. Chronic stress, glucocorticoid receptor resistance, inflammation, and disease risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):5995–9.

Carraca EV, Encantado J, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, et al. Effect of exercise training on psychological outcomes in adults with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 2021;22 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):e13261.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants for their support of the present study. We would also like to thank Mr. Tim Wiseman for the English editing of the paper.

Funding

This project was supported by the Faculty Collaborative Research Scheme between Social Sciences and Health Sciences of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University awarded to CYYL (Grant No.: 1-ZVQ2), and the Start-up Fund for RAPs under the Strategic Hiring Scheme of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University awarded to LHC (Grant No: 1-BD7D). The funders have no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, preparation of the manuscript, and decision about its publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Y.Y.L. was involved in study design, data collection and drafting the manuscript. F.H.Y.L., A.W.T.F., and S.S.M.N. were responsible for the study design. L.H.C. contributed to the study design, data analysis, drafting the manuscript, and the overall reviewing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participants

This study was approved by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent before enrolment in the present study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (declarations of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, C.Y.Y., Chen, L.H., Lai, F.H.Y. et al. The association between satisfaction with life and anxiety symptoms among Chinese elderly: a moderated mediation analysis. BMC Geriatr 23, 855 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04490-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04490-0