Abstract

Background

The association between sensory impairment including vision impairment (VI), hearing impairment (HI), dual impairment (DI) and the functional limitations of SCD (SCD-related FL) are still unclear in middle-aged and older people.

Methods

162,083 participants from BRFSS in 2019 to 2020 was used in this cross-sectional study. After adjusting the weights, multiple logistic regression was used to study the relationship between sensory impairment and SCD or SCD-related FL. In addition, we performed subgroup analysis on the basis of interaction between sensory impairment and covariates.

Results

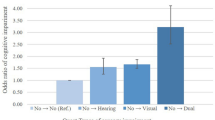

Participants who reported sensory impairment were more likely to report SCD or SCD-related FL compared to those without sensory impairment (p < 0.001). The association between dual impairment and SCD-related FL was the strongest, the adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were [HI, 2.88 (2.41, 3.43); VI, 3.15(2.61, 3.81); DI, 6.78(5.43, 8.47)] respectively. In addition, subgroup analysis showed that men with sensory impairment were more likely to report SCD-related FL than women, the aORs and 95% CI were [HI, 3.15(2.48, 3.99) vs2.69(2.09, 3.46); VI,3.67(2.79, 4.83) vs. 2.86(2.22, 3.70); DI, 9.07(6.67, 12.35) vs. 5.03(3.72, 6.81)] respectively. The subject of married with dual impairment had a stronger association with SCD-related FL than unmarried subjects the aOR and 95% CI was [9.58(6.69, 13.71) vs. 5.33(4.14, 6.87)].

Conclusions

Sensory impairment was strongly associated with SCD and SCD-related FL. Individuals with dual impairment had the greatest possibility to reported SCD-related FL, and the association was stronger for men or married subjects than other subjects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) is the self-perceived perception of ongoing cognitive decline, and it typically takes the form of a fall in self-perceived memory loss [1, 2]. As an early marker of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, SCD has attracted more and more attention from scientists in recent years [2,3,4]. The number of people with SCD was increasing along with the proportion of the elderly population increased. Meanwhile, the functional limitations followed by SCD imposed a huge economic burden on both the family and society. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2015–2016, more than 10% of people aged 45 and older reported SCD [5].

Vision impairment and hearing impairment are also very common in the context of population aging [6,7,8,9]. According to the statistics, more than 5 million suffered vision impairment in the world and 5% of global population was affected by hearing impairment [10,11,12,13]. Meanwhile, People with dual sensory impairment accounted for 0.2-2% population of the world [14]. Some studies pointed out vision impairment (VI) and hearing impairment (HI) were major risk factors for cognitive decline [15,16,17]. Dual sensory impairment (DI) was associated with a significantly increased risk of cognitive decline due to lack of vision or hearing sensory compensation compared with single vision or hearing impairment [18]. However, there are also different results on the association between the sensory impairment and cognitive decline, a cohort study of hearing impairment and cognitive function showed that hearing loss accelerated cognitive decline but the association was not found after adjusting for age [19]. In 2015–2016, more than half of participants with SCD reported functional limitations related to SCD [20]. Previous studies examined the association between sensory impairment and cognitive decline and a study among those showed dual impairment was associated with cognitive decline [21,22,23]. But few studies explored directly association between sensory impairment and functional limitations of subjective cognitive decline. Although a recent study suggested that people with vision impairment were significantly more likely to report SCD-related FL than those without visual impairment [24]. Older people with visual impairment were more likely to suffer from hearing impairment [25]. There is a lack of evidence of association between hearing impairment or dual impairment and SCD-related functional limitations. Therefore, it is extremely important to study the relationship between sensory impairment (HI, VI, DI) and SCD-related functional limitations.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the association between sensory impairment and SCD or SCD-related functional limitations and to comprehensively assess the impact of the former on latter in a large and representative sample of U.S. adults.

Method

Data source and study samples

The source of current study data was the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) established by the Centers for Disease control and Prevention (CDC)[26]. BRFSS is a nationwide, cross-sectional telephone survey that collects annually the data of U.S. residents aged ≥ 18 concerning health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services. As far, BRFSS has collected data in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia and three U.S. territories. To increase the sample size, the research used the data from 2019 to 2020. Among two years, there were totally 48 states chose the module of “cognitive decline” in their surveys. The current study adjusted the survey weights as well as combined the data 2019 and the data of 2020 according to the rule of complex weight of CDC to enhance the representativeness of the sample.

In our study, the initial database included 357,564 samples during 2019–2020. After excluding individuals aged less than 45, lacking information on SCD and SCD-related limitations, vision and hearing impairment and covariate, 162,083 individuals were included the study (Fig. 1).

Measures

BRFSS questionnaire included three parts: core questions (for all states in the US), optional modules and state-added questions. “Cognitive decline” and “Dual impairment (vision impairment and hearing impairment)” were included respectively in an optional module and a core question.

Among all respondents aged ≥ 45, those answered “yes” for “During the past 12 have you experienced confusion or memory loss that is happening more often or is getting worse?” was defined SCD. On this basis, those were classified as SCD-related functional limitations if they answer “usually”, “always” or “sometimes” for one or more of follow-up two questions: “During the past 12 months, as a result of confusion or memory loss, how often have you given up day-to-day household activities or chores you used to do (e.g., cooking, cleaning, taking medications, driving, or paying bills)?”and “During the past 12 months, how often has confusion or memory loss interfered with your ability to work, volunteer, or engage in social activities outside the home?”; On the contrary, those answered “rarely”, “never” were defined as no SCD-related functional limitations.

Sensory impairment (VI, HI, DI)

Respondents who replied “yes” for the question “Are you blind or do you have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses?” was regarded as vision impairment. Hearing was accessed through the question: “Are you deaf or do you have serious difficulty hearing?”, respondents had a yes answer were defined as hearing impairment. Respondents who had both vision impairment and hearing impairment were defined as dual impairment.

Covariates

The present study included variables that may confound the association between dual impairment and subjective cognitive decline. Demographic variables included age group (45–64, 65–74, ≥ 75), sex (men or women), race (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic multiracial, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), marital status (married or other), body mass index(BMI)(underweight [< 18.5], normal weight [18.5–24.9], overweight [25-29.9], obese [≥ 30]), educational level (less than high school graduate, high school graduate/some college, college graduate) and income level (< 15,000, 15,000–25,000, 25,000–35,000, 35,000–50,000, ≥ 50,000). Behavioral and health status variables included smoking status (yes or no), drinking status (yes or no), exercise (yes or no), any chronic diseases (yes or no). Chronic diseases included diabetes, angina or coronary heart disease, stroke and cancer. Among those, BMI was calculated based on self-reported height and weight.

Statistical analysis

In our analysis, we described the distribution of all samples by three subgroups. All variables were presented with weighted percentages and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Comparisons between different groups were performed using chi-square test. Multivariate logistic regression with complex weighting was used to estimate the association of sensory impairment with SCD or SCD-related functional limitations and explore interaction between sensory impairment and covariates. We built three models to calculate and report odds ratios (OR) of the outcomes, with the corresponding 95% CI. Model I did not include any covariables. Model II adjusted for age and sex. Model III adjusted for all covariables (age, sex, marital status, BMI, educational level, income level, smoking status, exercise and chronic diseases). The above analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 24.0. In addition, subgroup analysis plot was conducted using forest plot package for R Version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All p value was two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of all populations and groups classified by with or without SCD and SCD-related functional limitations are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Among 162,083 individuals, 15,706(9.7%) participants had SCD and 6524(4.0%) had SCD-related FL. In comparison with individuals reported no SCD, a higher proportion of individuals of SCD with or without SCD-related FL reported sensory impairment (HI:7.3%vs19.0%vs15.7%, VI:3.8%vs6.5%vs17.1%, DI:1.0%vs2.6%8.8%). In addition, participants reported SCD-related FL were more likely to be women, smoker, unmarried, no exerciser, people with any chronic disease than the other two groups(p < 0.001).

The result of the association between sensory impairment and SCD or SCD-related functional limitations are showed in Table 3. We found that sensory impairment was associated with SCD and SCD-related functional limitations in the unadjusted model [SCD, without SCD-related FL: HI, 3.18(95%CI, 2.75–3.68), VI, 2.10(95%CI, 1.69–2.60), DI, 3.14(95%CI, 2.45–4.03); SCD, with SCD-related FL: HI, 3.25(95%CI, 2.76–3.84), VI, 6.75(95%CI, 5.69-8.00), DI, 13.19(95%CI, 10.67–16.30)]. The association still existed after adjusting age, sex, race, marital status, BMI, educational level, income level, smoking status, binge drinking, exercise, chronic diseases. The association between the dual impairment and the SCD-related FL was the strongest, followed by vision impairment. Hearing impairment had the weakest association with SCD-related FL. [SCD, without SCD-related FL: HI, 2.49(95%CI, 2.14–2.90), VI, 1.73(95%CI, 1.38–2.16), DI, 2.31(95%CI, 1.78–2.98); SCD, with SCD-related FL: HI, 2.88(95%CI, 2.41–3.43)], VI, 3.15(95%CI, 2.61–3.81), DI, 6.78(95%CI, 5.43–8.47)].

The results of the interaction are shown in Fig. 2, and our results indicated that there was an interaction between age or sex or race or BMI or marital status or educational level or chronic diseases and sensory impairment in the association of sensory impairment and SCD-related FL (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). On the basis, we performed subgroups analysis and found that the association between sensory impairment (HI, VI, DI) and SCD-related FL was consistent with all study subjects in subgroups of age, sex, marital status, educational level and chronic diseases (STable1-4 and 7). In addition, the result showed that sensory impairment was more significantly associated with SCD-related FL in men than in women [(HI, 3.15(95%CI, 2.48–3.99) vs. 2.69(95%CI, 2.09–3.46); VI, 3.67(95%CI, 2.79–4.83) vs. 2.86(95%CI, 2.22–3.70); DI, 9.07(95%CI, 6.67–12.35) vs. 5.03(95%CI, 3.72–6.81)] (STable1). Among different marital status, the association of dual impairment with SCD-related FL was stronger in married subjects than in other subjects [9.58(95%CI, 6.69–13.71) vs. 5.33(95%CI, 4.14–6.87)] (STable2). In the Underweight group, the association between HI (2.13; 95%CI, 0.80–5.65) or VI (2.15; 95%CI, 0.91–5.08) and SCD-related FL was not obvious (STable5).

The relationship between dual sensory impairment and SCD, with SCD-related FL according to different subgroups. SCD, subjective cognitive decline, FL, functional limitations, NH, non-hispanic, LH, less than high school graduate, HG/SC, High school graduate/some college, CG, College graduate, NSI, no sensory impairment, HI, hearing impairment, VI, Vision impairment, DI, dual impairment, CD, chronic diseases, NCD, no chronic diseases

In addition, we conducted a sensitivity analysis among those without hypertension or depression and discovered that the results were consistent with those of the total population. Sensory impairment was positively correlated with SCD or SCD-related FL. People with dual impairment were more likely to have SCD or SCD-related FL (STable8, STable9).

Discussion

In this study, we found that sensory impairment was strongly associated with SCD and SCD-related functional limitations. Furthermore, the possibility of SCD-related functional limitations was more than twice as high in the presence of dual impairment as in the presence of single sensory impairment. Results of subgroup analysis showed that dual impairment was more strongly associated with SCD-associated FL in men or married subjects than in other subjects.

Our findings were consistent with the results of previous studies which suggested that sensory impairment was relevant to cognitive decline [19, 52]. In addition, people with dual impairment were more likely to report SCD-related FL due to lack of compensatory vision or hearing [18].

Although the mechanism regarding the relationship between sensory impairment and SCD or SCD-related FL was not clear, some cohort studies found that some individuals improved cognitive function after cataract surgery after cataract surgery or after the use of hearing-aid [53, 54]. Therefore, recognition and intervention of hearing impairment and visual impairment in the early stage can slow down the rate of cognitive decline and reduce the damage to independent living ability and social ability.

In subgroup analysis, our study also found that men who reported sensory impairment (one or both) were more likely to reported SCD-related FL than women. Our conclusion supported some studies which investigated gender differences in SCD and found that men were far more likely to report SCD than women [55, 56]. In addition, a study on the differences in cognitive function of Intensive Care Unit Survivors indicated that compared with women, although men had a lower risk of cognitive decline, they were more affected by cognitive decline [57]. One possible explanation is that sensory impairment may contribute to social network poverty, which altered brain structure and affected cognitive function by increasing inflammation and glucocorticoid levels. One study showed that social disengagement was more strongly associated with cognitive decline in men than women [43, 58], so men with sensory impairments were more likely to report SCD and related functional limitations. In addition, our study found a stronger link between dual impairment and SCD-related FL in the married people. The reason for this may be that, compared to the unmarried people, married people with disablement were more likely to be cared for by their families, which may aggravate functional limitations [59]. The married with dual impairment may receive less external stimulation including sensory stimulation (taste, skin sensation and so on) due to their family members taking care of them and sharing their household responsibility, which may in turn lead to cognitive decline and SCD-related FL. In addition, more researches may be needed to explore their relationship. This study has some advantages. Firstly, we stratified appropriately and weighted the data and conducted analyses with complex sampling procedures in our work, which can reduce potential bias and increase the reliability of the results. Secondly, our study is the first to explore the association between hearing impairment, dual impairment, and SCD-related functional limitations in middle-aged and elderly people. Thirdly, we conducted a subgroup analysis to observe the relationship between sensory impairment and SCD-related functional limitations in different subgroups.

However, our study has several limitations. Firstly, BRFSS is a sectional study, we could not clear the causal association between sensory impairment and SCD-related functional limitations. Secondly, the BRFSS database collects information in the form of telephone survey. Since the definition of SCD and sensory disorders are subjective, it could be prone to bias. Thirdly, the BRFSS survey did not include adults living in long-term care facilities, prisons, and other facilities; therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to these populations.

Conclusions

The study found that sensory impairment was associated with SCD and SCD-related functional limitations. The association was strongest for individuals with dual impairment. In addition, men with sensory impairment (VI or HI or DI) were more likely to report SCD-related functional limitations than women. The married subjects with dual impairment had stronger association with SCD-related FL than unmarried subjects. The compensatory role of another sensation is very important when suffering from a single sensory impairment. We should pay more attention to the middle-aged and older people with sensory impairment especially dual impairment.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available in the [BRFSS] repository, [https://www.cdc.gov/brfss].

Abbreviations

- SCD:

-

Subjective cognitive decline

- SCD-related FL:

-

Functional Limitations of Subjective cognitive decline

- VI:

-

Vision impairment

- HI:

-

Hearing impairment

- DI:

-

Dual impairment

- BRFSS:

-

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease control and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Desai R, Whitfield T, Said G, John A, Saunders R, Marchant NL, et al. Affective symptoms and risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in subjective cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;71:101419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2021.101419.

Wang XT, Wang ZT, Hu HY, Qu Y, Wang M, Shen XN, et al. Association of Subjective Cognitive decline with risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of prospective longitudinal studies. J Prev Alzheimer’s disease. 2021;8(3):277–85. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2021.27.

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2014;10(6):844–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.01.001.

Lauriola M, Esposito R, Delli Pizzi S, de Zambotti M, Londrillo F, Kramer JH, et al. Sleep changes without medial temporal lobe or brain cortical changes in community-dwelling individuals with subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2017;13(7):783–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.11.006.

Lee JE, Ju YJ, Park EC, Lee SY. Effect of poor sleep quality on subjective cognitive decline (SCD) or SCD-related functional difficulties: results from 220,000 nationwide general populations without dementia. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:32–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.082.

Verbeek E, Drewes YM, Gussekloo J. Visual impairment as a predictor for deterioration in functioning: the Leiden 85-plus study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):397. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-03071-x.

Shen H, Zhang H, Gong W, Qian T, Cheng T, ** L, et al. Prevalence, causes, and factors Associated with Visual Impairment in a chinese Elderly Population: the Rugao Longevity and Aging Study. Clin Interv Aging. 2021;16:985–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.S304730.

Gbessemehlan A, Guerchet M, Helmer C, Delcourt C, Houinato D, Preux PM. Association between visual impairment and cognitive disorders in low-and-middle income countries: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(10):1786–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1808878.

Powell DS, Oh ES, Lin FR, Deal JA. Hearing impairment and cognition in an Aging World. J Association Res Otolaryngology: JARO. 2021;22(4):387–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-021-00799-y.

Ehrlich JR, Ramke J, Macleod D, Burn H, Lee CN, Zhang JH, et al. Association between vision impairment and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global health. 2021;9(4):e418–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(20)30549-0.

Lim ZW, Chee ML, Soh ZD, Cheung N, Dai W, Sahil T, et al. Association between visual impairment and decline in cognitive function in a multiethnic Asian Population. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(4):e203560. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3560.

Ding N, Lee S, Lieber-Kotz M, Yang J, Gao X. Advances in genome editing for genetic hearing loss. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2021;168:118–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2020.05.001.

Li LYJ, Wang SY, Wu CJ, Tsai CY, Wu TF, Lin YS. Screening for hearing impairment in older adults by smartphone-based Audiometry, Self-Perception, HHIE Screening Questionnaire, and free-field Voice Test: comparative evaluation of the Screening Accuracy with Standard pure-tone Audiometry. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2020;8(10):e17213. https://doi.org/10.2196/17213.

Pardhan S, López Sánchez GF, Bourne R, Davis A, Leveziel N, Koyanagi A, et al. Visual, hearing, and dual sensory impairment are associated with higher depression and anxiety in women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36(9):1378–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5534.

Curhan SG, Willett WC, Grodstein F, Curhan GC. Longitudinal study of hearing loss and subjective cognitive function decline in men. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2019;15(4):525–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.11.004.

Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, Tampubolon G, Pendleton N. Visual and hearing impairments are associated with cognitive decline in older people. Age Ageing. 2018;47(4):575–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy061.

Curhan SG, Willett WC, Grodstein F, Curhan GC. Longitudinal study of self-reported hearing loss and subjective cognitive function decline in women. Alzheimer’s Dement J Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2020;16(4):610–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.08.194.

Kuo PL, Huang AR, Ehrlich JR, Kasper J, Lin FR, McKee MM, et al. Prevalence of concurrent functional vision and hearing impairment and Association with Dementia in Community-Dwelling Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Netw open. 2021;4(3):e211558. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1558.

Croll PH, Vinke EJ, Armstrong NM, Licher S, Vernooij MW, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in the general population: a prospective cohort study. J Neurol. 2021;268(3):860–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10208-8.

Taylor CA, Bouldin ED, McGuire LC. Subjective cognitive decline among adults aged ≥ 45 years - United States, 2015–2016. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018;67(27):753–7. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6727a1.

Fang IM, Fang YJ, Hu HY, Weng SH. Association of visual impairment with cognitive decline among older adults in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17593. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-97095-9.

Lin FR, Yaffe K, **a J, Xue QL, Harris TB, Purchase-Helzner E, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):293–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868.

Tomida K, Lee S, Bae S, Harada K, Katayama O, Makino K, et al. Association of dual sensory impairment with Cognitive decline in older adults. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2022;51(4):322–30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000525820.

Saydah S, Gerzoff RB, Taylor CA, Ehrlich JR, Saaddine J. Vision Impairment and Subjective Cognitive decline-related functional Limitations - United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019;68(20):453–7. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6820a2.

Chia EM, Mitchell P, Rochtchina E, Foran S, Golding M, Wang JJ. Association between vision and hearing impairments and their combined effects on quality of life. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago Ill: 1960). 2006;124(10):1465–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.124.10.1465.

Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System(BRFSS.) [https://www.cdc.gov/brfss]

Lin MY, Gutierrez PR, Stone KL, Yaffe K, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, et al. Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):1996–2002. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52554.x.

Ge S, McConnell ES, Wu B, Pan W, Dong X, Plassman BL. Longitudinal Association between hearing loss, Vision loss, dual sensory loss, and Cognitive decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):644–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16933.

Parada H, Laughlin GA, Yang M, Nedjat-Haiem FR, McEvoy LK. Dual impairments in visual and hearing acuity and age-related cognitive decline in older adults from the Rancho Bernardo Study of healthy aging. Age Ageing. 2021;50(4):1268–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afaa285.

Marrone N, Ingram M, Bischoff K, Burgen E, Carvajal SC, Bell ML. Self-reported hearing difficulty and its association with general, cognitive, and psychosocial health in the state of Arizona, 2015. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):875. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7175-5.

Ibnidris A, Robinson JN, Stubbs M, Piumatti G, Govia I, Albanese E. Evaluating measurement properties of subjective cognitive decline self-reported outcome measures: a systematic review. Syst reviews. 2022;11(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-022-02018-y.

Wen C, Bi YL, Hu H, Huang SY, Ma YH, Hu HY, et al. Association of Subjective Cognitive decline with cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology in Cognitively Intact older adults: the CABLE study. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2022;85(3):1143–51. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-215178.

Hu W, Wang Y, Wang W, Zhang X, Shang X, Liao H, et al. Association of Visual, hearing, and dual sensory impairment with Incident Dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:872967. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.872967.

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Buckley RF, van der Flier WM, Han Y, Molinuevo JL, et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(3):271–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30368-0.

Assi L, Ehrlich JR, Zhou Y, Huang A, Kasper J, Lin FR, et al. Self-reported dual sensory impairment, dementia, and functional limitations in Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):3557–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17448.

Wayne RV, Johnsrude IS. A review of causal mechanisms underlying the link between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;23(Pt B):154–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2015.06.002.

Eckert MA, Vaden KI Jr, Dubno JR. Age-related hearing loss Associations with changes in brain morphology. Trends in hearing. 2019;23:2331216519857267. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216519857267.

Powell DS, Oh ES, Reed NS, Lin FR, Deal JA. Hearing loss and cognition: what we know and where we need to go. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:769405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.769405.

Liang L, Chen Z, Wei Y, Tang F, Nong X, Li C, et al. Fusion analysis of gray matter and white matter in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment by multimodal CCA-joint ICA. NeuroImage Clin. 2021;32:102874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102874.

Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2322–6. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000147473.04043.b3.

Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, Tampubolon G, Pendleton N. Associations between Self-Reported sensory impairment and risk of Cognitive decline and impairment in the Health and Retirement Study Cohort. The journals of gerontology Series B Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2020;75(6):1230–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz043.

Whitson HE, Cronin-Golomb A, Cruickshanks KJ, Gilmore GC, Owsley C, Peelle JE et al. American Geriatrics Society and National Institute on Aging Bench-to-Bedside Conference: Sensory Impairment and Cognitive Decline in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2018, 66(11):2052–2058. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15506

Brenowitz WD, Kaup AR, Lin FR, Yaffe K. Multiple Sensory Impairment Is Associated With Increased Risk of Dementia Among Black and White Older Adults. The journals of gerontology Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2019, 74(6):890–896. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly264

Luo DH, Tseng WI, Chang YL. White matter microstructure disruptions mediate the adverse relationships between hypertension and multiple cognitive functions in cognitively intact older adults. NeuroImage. 2019;197:109–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.04.063.

Carnevale L, D’Angelosante V, Landolfi A, Grillea G, Selvetella G, Storto M, et al. Brain MRI fiber-tracking reveals white matter alterations in hypertensive patients without damage at conventional neuroimaging. Cardiovascular Res. 2018;114(11):1536–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvy104.

Moroni F, Ammirati E, Hainsworth AH, Camici PG. Association of White Matter Hyperintensities and Cardiovascular Disease: the importance of Microcirculatory Disease. Circulation Cardiovasc imaging. 2020;13(8):e010460. https://doi.org/10.1161/circimaging.120.010460.

Austin TR, Nasrallah IM, Erus G, Desiderio LM, Chen LY, Greenland P, et al. Association of Brain volumes and White Matter Injury with race, ethnicity, and Cardiovascular Risk factors: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Association. 2022;11(7):e023159. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.121.023159.

Cyarto EV, Lautenschlager NT, Desmond PM, Ames D, Szoeke C, Salvado O, et al. Protocol for a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of physical activity on delaying the progression of white matter changes on MRI in older adults with memory complaints and mild cognitive impairment: the AIBL active trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(167). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-12-167.

Zhao H, Cheng J, Liu T, Jiang J, Koch F, Sachdev PS, et al. Orientational changes of white matter fibers in Alzheimer’s disease and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2021;42(16):5397–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25628.

Wang Z, Williams VJ, Stephens KA, Kim CM, Bai L, Zhang M, et al. The effect of white matter signal abnormalities on default mode network connectivity in mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41(5):1237–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.24871.

Harithasan D, Mukari SZS, Ishak WS, Shahar S, Yeong WL. The impact of sensory impairment on cognitive performance, quality of life, depression, and loneliness in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(4):358–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5237.

Liu CJ, Chang PS, Griffith CF, Hanley SI, Lu Y. The Nexus of sensory loss, cognitive impairment, and functional decline in older adults: a sco** review. Gerontologist. 2022;62(8):e457–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab082.

Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo YF, DiNuzzo AR, Ray LA, Raji MA, Markides KS. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: data from the hispanic established populations for epidemiologic studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):681–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x.

Hong T, Mitchell P, Burlutsky G, Liew G, Wang JJ. Visual impairment, hearing loss and cognitive function in an older Population: longitudinal findings from the Blue Mountains Eye Study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147646. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0147646.

Brown MJ, Patterson R. Subjective cognitive decline among sexual and gender minorities: results from a U.S. Population-Based sample. J Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 2020;73(2):477–87. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-190869.

Wang L, Tian T. Gender differences in Elderly with Subjective Cognitive decline. Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:166. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2018.00166.

Son YJ, Song HS, Seo EJ. Gender differences regarding the impact of change in cognitive function on the functional status of Intensive Care Unit Survivors: a prospective cohort study. J Nurs scholarship: official publication Sigma Theta Tau Int Honor Soc Nurs. 2020;52(4):406–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12568.

Oh SS, Cho E, Kang B. Social engagement and cognitive function among middle-aged and older adults: gender-specific findings from the korean longitudinal study of aging (2008–2018). Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95438-0.

Kail BL. Marital status as a moderating factor in the process of disablement. J Aging Health. 2016;28(1):139–64.https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264315589572.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81973129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BL, RG, and XL made the study design; RG, MS, YW conducted the study; RG, XL, and JL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; XW, ZX, NY and YY attended original manuscript revision; LJ provided guidance in the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, R., Li, X., Sun, M. et al. Vision impairment, hearing impairment and functional Limitations of subjective cognitive decline: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr 23, 230 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03950-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03950-x