Abstract

Background

Renal cystic diseases are one of the commonest renal lesions encountered in clinical practice. Although common, most of the cysts are solitary, benign, asymptomatic and seldom clinically significant. But, renal lymphangiectasia is an exception. These are rare lymphatic malformation seen around the kidneys and in the retroperitoneum. It masquerades clinically like ADPKD and renal tumors and radiologically like a complex renal cyst. Although the cyst is benign, it possesses a significant impact on the quality of life. Because of its rarity, the management of this condition has not been well defined in the literature. A clinician must be aware of this rare condition and able to differentiate it from other similar conditions to aid in appropriate management. Hence, we present a case report of a female with bilateral renal lymphangiectasia managed successfully by laparoscopic excision.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old hypertensive female came with complaints of bilaterally progressive flank masses for 3 months and breathlessness for 2 weeks. On examination, she had bilateral pitting pedal edema, bilateral palpable renal mass and ascites. She had nephrotic range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and normal renal function. Imaging showed 22-cm bilateral peri-renal and hilar multi-loculated cystic lesions, suggestive of bilateral renal lymphangiectasia. Antihypertensives and percutaneous interventions were not successful in relieving her symptoms. Subsequently, she was managed with laparoscopic excision on both sides. After surgery, she had an uneventful postoperative period and good symptomatic relief. No recurrence of the lesion found in follow-up CT imaging after 18 months.

Conclusions

Renal lymphangiectasia is a rare yet clinically significant cystic lesion of the kidney. It can be diagnosed confidently by noninvasive imaging modalities. Medical treatment offered for mild symptomatic disease. Patients with severe symptoms need surgical intervention especially if it is not responding to medical management. Minimal invasive approach is feasible and successful in the management of this voluminous disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction and Background

Renal lymphangiectasia is a rare benign lymphatic anomaly of the kidneys accounting for < 1% of all lymphangiectasia. It is also known as renal hygroma, renal lymphangiomatosis, polycystic disease of the renal sinus and renal lymphatic malformations (RLM). It can be unilateral or bilateral, focal or diffuse. It shows familial predilection, seen in both children and adult with male predominance in the ratio of 3:1. It can be peri-nephric, intra-renal or para-pelvic. These are usually multi-loculated as seen in our patient. The etiology is unclear. The probable postulate for the etiology is developmental anomaly where communication between peri-renal lymphatic channels and main retroperitoneal lymphatic channels fails to be established. This causes dilatation of lymphatic channels resulting in cystic dilatation [1, 2]. Acquired renal lymphangiectasia after renal transplantation is also reported in the literature [8].

Most patients are asymptomatic. Flank mass is the common presenting symptom. It is reported to be exacerbated during pregnancy. Cysts might cause renin-dependent hypertension in 10% of patients. In our patients, the need for antihypertensives decreased with surgical management. The reason for hypertension is page kidney. Gross proteinuria due to associated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis or excess tubular pressure due to lymphatic block may be seen in few individuals. Hypoalbuminemia severe enough to cause pedal edema or ascites could be an indication for intervention. Proteinuria may also predispose to renal vein thrombosis [1, 2]. Renal atrophy is a rare complication in bilateral cases [3, 4].

Ultrasonogram (USG) is the initial radiological investigation. The findings are peri-nephric and hilar anechoic lesions with internal septations due to the multiple thin loculations in a honey comb pattern. Contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) is diagnostic in most instances. The lymphangiectasia are hypodense (0–10 Hounsfield unit), non-enhancing, non-communicating and located around kidneys as well as renal pelvis. They may show extension into retroperitoneum. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the lesion appears hypointense in T1WI and hyperintense in T2WI with reversal of cortico-medullary intensity. But, MRI is rarely required for diagnosis. Shrewd recognition of these radiological features will differentiate this condition from other diseases such as ADPKD and cystic renal tumor and also obviate the need for other invasive investigations such as cytology and tissue biopsy [1, 2].

No active intervention is required in asymptomatic patients. Complications like hypertension and ascites can be managed medically. Intractable cases and mass effect symptoms need palliation by percutaneous drainage. Failure rates with percutaneous drainage are very high because of multiple loculations, as in our patient [1]. Sclerotherapy has been reported but requires several sessions. Sclerotherapy is not suitable for para-pelvic and peri-pelvic cysts because of the risk of PUJ obstruction [5].

Deroofing is also helpful in some instances, but loculatios could be a hindrance. Complete excision is the surgical option with high success rate in individuals like our patient who could not be salvaged with other less invasive measures. Nephrectomy is very rarely indicated. Laparoscopy excision has not been reported in literature. Our patient was managed by laparoscopic excision. With laparoscopic excision of the lesion, exposed peritoneum over the lesion provides alternative drainage pathway for lymph [6, 7]. Laparoscopy helps in early recovery and decreases the morbidity compared to open procedure. Caution while excising close to parenchyma and renal pelvis. DJ stenting helps in identification of ureters. Recurrence is rare.

1.1 Case presentation

A 34-year-old female came with complaints of gradually increasing abdominal distension, primarily in the flanks, for the previous 3 months. She also had worsening breathlessness for the previous 2 weeks. She did not have lower urinary tract symptoms or hematuria. She was a hypertensive, on medical treatment for hypertension for the last 1 year. On examination, she had bilateral pitting pedal edema and bilateral palpable renal mass and ascites. She had nephrotic range proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia and normal renal function (serum creatinine 0.8 mgs%).

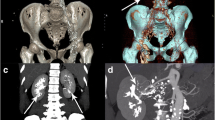

On USG imaging of kidneys, an approximately 20-cm bilateral perinephric and hilar anechoic lesions with internal septations (Fig. 1) was seen. Subsequently, CECT of kidneys showed bilateral hypodense non-enhancing non-communicating lesions around both kidneys measuring 22 × 12 cm suggestive of bilateral renal lymphangiectasia (Fig. 2).

CECT features of renal lymphangiectasia. Coronal view of CECT of kidneys in non-contrast phase (a) and delayed phase (b). In non-contrast phase, the lesions are difficult to be differentiated from renal parenchyma and pelvicalyceal system. In delayed phase (b), the lymphangiectasia (white arrow) can be well differentiated from the enhancing renal parenchyma and pelvicalyceal system. These lesions are hypodense (0–10 Hounsfield unit), non-enhancing, non-communicating and located peri-renal as well as peri-pelvic

She was initially managed medically for hypertension and anasarca, but since she had persistent worsening of symptoms due to gross proteinuria, so she was planned for invasive intervention. Initially, percutaneous drainage was done, but due to the multi-loculated nature of the lesion, it was not successful and she had persistent symptoms. She was subsequently planned for laparoscopic excision. Under general anesthesia and lithotomy position, rigid cystoscopy was done. Lower urinary tract was normal. Bilateral ureteric stenting was done to aid in ureter identification during surgery. Then, the patient was placed in right lateral kidney position and laparoscopy done with three ports. Colon deflected and Gerota’s fascia was opened to visualize the lesion. Grossly, the lesions were multi-loculated containing clear fluid and located all around the kidneys (Fig. 3). There was no clear surgical plane between the cyst and renal capsule. So, excision was done till renal parenchyma is exposed. Minimal cysts along the posterior surface close to hilum were left due to risk of renal vessel injury. Procedure was repeated on the opposite side, and the specimen was removed. No blood transfusions required. She had persistent drain output of more than 500 ml per day for initial 3 days, which gradually reduced and drain was removed after 7 days. Histopathology featured flat endothelium lined channels with renal tubules (Fig. 4). She had good symptomatic improvement and had relief of symptoms after surgery. There is no recurrence in CT imaging after 18 months (Fig. 5).

Preoperative and postoperative follow up CT image of renal lymphangiectasia. On comparing the preoperative CT image (a) of RLM with postoperative CT image (b) taken 18 months after bilateral laparoscopic excision of lymphangiectasia, no recurrence of the lesion (white arrows above the anterior surface of kidneys indicates the area of concern) is evident

2 Conclusions

Renal lymphangiectasia is a rare yet clinically significant benign cystic lesion of the kidney. Although rare, it is a potential cause for renal failure if bilateral. The management of this condition depends on diagnosis, its impact on the renal function primarily and size of the mass to a certain extent. Mild symptoms can be offered medical management. Patients with severe symptoms need surgical management of the lymphangiectasia, especially if not responding to medical management. Minimally invasive approach is feasible in such voluminous disease and is associated with less morbidity and comparable success rate.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Umapathy S, Alavandar E, Renganathan R, Thambidurai S, Venkatesh KA (2020) Renal lymphangiectasia: an unusual mimicker of cystic renal disease–a cases series and literature review. Cureus 12(10):e10849

Vaidehi KP, Harsh CS, Shruti PG, Sajni IK, Himanshu VP, Maulin KS (2017) Role of CT scan in diagnosis of renal lymphangiectasia: our single-centre expeience. Ren Fail 39:533–539

Magu S, Agarwal S, Dalaal SK (2010) Bilateral renal lymphangioma–an incidental finding. Indian J Nephrol 20:114–115

Bansal K, Sureka B, Pargewar S, Arora A (2016) Renal lymphangiectasia: one disease, many names! Indian J Nephrol 26:57–58

Alshanafey S, Alkhani A, Alkibsib A (2022) Renal lymphangiectasia in pediatric population: case series and review of literature. Ann Saudi Med 42(2):139–144

Rajeev TP, Barua S, Deka PM, Hazarika S (2006) Bilateral perirenallymphangiomatosis: a case report. Indian J Urol 22:73–74

Meyyappan RM, Ravikumar S, Gopinath M (2013) Laparoscopic management in a rare case of bilateral perirenallymphangiomatosis. Indian J Urol 29:73–74

Hamroun A, Puech P, Maanaoui M, Bouye S, Hazzan M, Lionet A (2021) Renal lymphangiectasia, a rare complication after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int Rep 6:1475–1479

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In this case report, NV is the assistant surgeon, corresponding author, and contributed to data acquisition and initial drafting of the work. AM is the operating surgeon and contributed to substantive revision of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent to participate was obtained KMCH Ethics Committee approval obtained.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication was obtained from the patient and next of kin.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Venkatachalam, N., Murugesan, A. Bilateral renal lymphangiectasia: a rare renal cystic disease managed by minimal invasive approach—a case report. Afr J Urol 30, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-023-00399-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-023-00399-7