Abstract

Background

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) and malignant melanoma share overlap** immunohistochemistry with regard to the melanocytic markers HMB45, S100, and Melan-A. However, the translocation t(12; 22)(q13; q12) is specific to CCS. Therefore, although these neoplasms are closely related, they are now considered to be distinct entities. However, the translocation is apparently detectable only in 50%–70% of CCS cases. Therefore, the absence of a detectable EWS/AFT1 rearrangement may occasionally lead to erroneous exclusion of a translocation-negative CCS. Therefore, histological assessment is essential for the correct diagnosis of CCS. Primary CCS of the bone is exceedingly rare. Only a few cases of primary CCS arising in the ulna, metatarsals, ribs, radius, sacrum, and humerus have been reported, and primary CCS arising in the pubic bone has not been reported till date.

Case presentation

We present the case of an 81-year-old man with primary CCS of the pubic bone. Histological examination of the pubic bone revealed monomorphic small-sized cells arranged predominantly as a diffuse sheet with round, hyperchromatic nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli. The cells had scant cytoplasm, and the biopsy findings indicated small round cell tumor (SRCT). Immunohistochemical staining revealed the tumor cells to be positive for HMB45, S100, and Melan-A but negative for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and epithelial membrane antigen. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of primary CCS of the pubic bone resembling SRCT. This ambiguous appearance underscores the difficulties encountered during the histological diagnosis of this rare variant of CCS.

Conclusion

Awareness of primary CCS of the bone is clinically important for accurate diagnosis and management when the tumor is located in unusual locations such as the pubic bone and when the translocation t(12; 22)(q13; q12) is absent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS) of soft tissue was formerly known as malignant melanoma of soft tissues because of the presence of melanin pigmentation and (pre-)melanosomes in a significant percentage of these tumors. CCS was originally described by Enzinger in 1965, and it has become a well-defined clinicopathological entity since then [1]. CCS and malignant melanoma share overlap** immunohistochemistry with regard to the melanocytic markers HMB45, S100, and Melan-A. However, CCS generally lacks melanoma-associated BRAF mutations [2–4]. In addition, the translocation t(12; 22)(q13; q12) is specific only to CCS [5] and results in fusion of EWS (22q12) and ATF1 (12q13). Therefore, although these neoplasms are closely related, they are now considered to be distinct entities. However, the translocation is apparently detectable only in 50%–70% of CCS cases. Absence of the detectable EWS/AFT1 rearrangement may occasionally lead to erroneous exclusion of a translocation-negative CCS. Therefore, histological assessment is essential for the correct diagnosis of CCS [6]. In addition, CCS accounts for <1% of soft tissue sarcomas, and this tumor is so rare that there are no standard regimens. It typically involves tendons and aponeuroses of young adults. Primary CCS of the bone is exceedingly rare. Only a few cases of primary CCS arising in the ulna, metatarsals, ribs, radius, sacrum, and humerus have been reported [7–9], and, to the best of our knowledge, CCS arising in the pubic bone has never been reported.

Case presentation

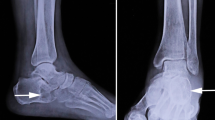

An 81-year-old man presented at our institution with right-sided groin pain since 2 months. He had no history of trauma, infection, or constitutional symptoms. Radiological examination on first admission revealed an expanding destructive lesion in the left superior pubic ramus. A technetium-99 m bone scan demonstrated activity in the left superior pubic ramus, and computed tomography (CT) revealed a mass encasing the left superior pubic ramus (Figure 1). Needle biopsy of the pubic bone was then performed. Histological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed monomorphic small cells arranged predominantly as a diffuse sheet. The cells had round hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and scant cytoplasm. These findings were indicative of small round cell tumor (SRCT; Figure 2A). On immunohistochemical staining, the tumor cells were positive for HMB45 (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA, USA; Figure 2B), S100 (DAKO, Carpenteria, CA; Figure 2C), and Melan-A (Novocastra, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, UK; Figure 2D), whereas they were negative for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3) and epithelial membrane antigen. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of the fusion signal of EWS located on chromosome 22q12 yielded negative results. BRAF (exons 11 and 15) mutation analysis by direct sequencing revealed the absence of mutations [4]. Although the biopsy specimen showed no obvious evidence of melanoma pigments, these findings suggested malignant melanoma or CCS. Whole-body CT, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, and 67Ga-citrare scintigraphy were performed to exclude the possibility of metastases of malignant melanoma to the bone. The patient was referred to a dermatologist for evaluation of primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. All efforts to find a primary lesion elsewhere were unsuccessful. Eventually, we concluded that this was not a metastatic lesion of malignant melanoma but primary CCS of the pubic bone. Because of the patient’s advanced age, he and his family refused surgery as well as local radiation therapy; instead, they opted for chemotherapy. The patient was administered DAV chemotherapy (a regimen of dimethyl triazeno imidazole carboxamide, 1-[4-amino-2-methyl-5-pyrimidinyl]-methyl-3-[2-chloroethyl]-3-nitrosourea hydrochloride, the available substitute for bischloroethylnitrosourea, and vincristine) [10, 11]; however, he died of progressive disease.

(A) Diffuse infiltration of small round cells with inconspicuous nucleoli and scanty cytoplasm (hematoxylin and eosin stain; objective magnification, ×40). (B) Abnormal cells positive for HMB45 (objective magnification, ×40). (C) Abnormal cells positive for S100. (objective magnification, ×40). (D) Abnormal cells positive for Melan-A. (objective magnification, ×40).

Discussion

CCS typically presents a uniform, nested-to-fascicular growth pattern. Tumor cells are polygonal or spindle-shaped with abundant cytoplasm. Less common morphologic variations include spindle-cell arrangement, marked pleomorphism, solid-cell aspect, microcystic aspect, and presence of myxoid stroma [12].

SRCT comprises heterogeneous neoplasms comprising relatively small, round-to-oval, closely-packed, undifferentiated cells with a high nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, scant cytoplasm, and round nuclei with evenly distributed, slightly coarse chromatin and small or inconspicuous nucleoli. SRCT comprises a group of highly aggressive malignant tumors [13]. Despite the similar morphology of CSS and SRCT under light microscopic examination, the latter differs from the former in that it includes pathological entities from vastly different lineages, including epithelial tumors such as small-cell carcinoma (poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma); mesenchymal tumors such as malignant solid neoplasms of childhood and other small round-cell sarcomas, and tumors with overlap** features such as lymphoma and melanoma [14]. Small-cell malignant melanoma with the appearance of SRCT is one of the recognized rare variants of malignant melanoma, and it is frequently documented as a complication of congenital melanocytic nevi [15], as a childhood neoplasm [16], or as a tumor of mucosal origin [17]. However, CCS resembling SRCT has not been previously reported.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of primary CCS of the pubic bone resembling SRCT. This ambiguous appearance underscores the difficulties encountered during the histological diagnosis of this rare variant of CCS. Awareness of primary CCS of the bone is clinically important for accurate diagnosis and management when the tumor is located in unusual locations such as the pubic bone and when the translocation t(12; 22)(q13; q12) is absent.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of data was obtained from the patient.

Abbreviations

- CCS:

-

Clear cell sarcoma

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- SRCT:

-

Small round cell tumor

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography.

References

Enzinger FM: Clear-cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses. An analysis of 21 cases. Cancer. 1965, 18: 1163-1174. 10.1002/1097-0142(196509)18:9<1163::AID-CNCR2820180916>3.0.CO;2-0.

Hocar O, Le Cesne A, Berissi S, Terrier P, Bonvalot S, Vanel D, Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Bui B, Coindre JM, Robert C: Clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma) of soft parts: a clinicopathologic study of 52 cases. Dermatol Res Pract. in press.

Panagopoulos I, Mertens F, Isaksson M, Mandahl N: Absence of mutations of the BRAF gene in malignant melanoma of soft parts (clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeuroses). Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005, 156: 74-76. 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.04.008.

Yang L, Chen Y, Cui T, Knösel T, Zhang Q, Geier C, Katenkamp D, Petersen I: Identification of biomarkers to distinguish clear cell sarcoma from malignant melanoma. Hum Pathol. in press.

Sandberg AA, Bridge JA: Updates on the cytogenetics and molecular genetics of bone and soft tissue tumors: clear cell sarcoma (malignant melanoma of soft parts). Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2001, 130: 1-7. 10.1016/S0165-4608(01)00462-9.

Langezaal SM, van Roggen JF G, Cleton-Jansen AM, Baelde JJ, Hogendoorn PC: Malignant melanoma is genetically distinct from clear cell sarcoma of tendons and aponeurosis (malignant melanoma of soft parts). Br J Cancer. 2001, 84: 535-538. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1628.

Liu X, Zhang H, Dong Y: Primary clear cell sarcoma of humerus: case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2011, 9: 163-10.1186/1477-7819-9-163.

Zhang W, Shen Y, Wan R, Zhu Y: Primary clear cell sarcoma of the sacrum: a case report. Skeletal Radiol. 2011, 40: 633-639. 10.1007/s00256-010-1077-z.

Hersekli MA, Ozkoc G, Bircan S, Akpinar S, Ozalay M, Tuncer I, Tandogan RN: Primary clear cell sarcoma of rib. Skeletal Radiol. 2005, 34: 167-170. 10.1007/s00256-004-0801-y.

Fujimoto M, Hiraga M, Kiyosawa T, Murakami T, Murata S, Ohtsuki M, Nakagawa H: Complete remission of metastatic clear cell sarcoma with DAV chemotherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003, 28: 22-24. 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01109.x.

Kato T, Suetake T, Sugiyama Y, Tabata N, Tagami H: Epidemiology and prognosis of subungual melanoma in 34 Japanese patients. Br J Dermatol. 1996, 134: 383-387. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb16218.x.

Sciot R, Speleman F: Clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Edited by: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. 2002, Lyon: IARC Press, 211-212.

Devoe K, Weidner N: Immunohistochemistry of small round-cell tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000, 17: 216-224.

Bahrami A, Truong LD, Ro JY: Undifferentiated tumor: true identity by immunohistochemistry. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008, 132: 326-348.

Hendrickson MR, Ross JC: Neoplasms arising in congenital giant nevi: morphologic study of seven cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981, 5: 109-135. 10.1097/00000478-198103000-00004.

Barnhill RL, Flotte TJ, Fleischli M, Perez-Atayde A: Cutaneous melanoma and atypical Spitz tumors in childhood. Cancer. 1995, 76: 1833-1845. 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10<1833::AID-CNCR2820761024>3.0.CO;2-L.

Franquemont DW, Mills SE: Sinonasal malignant melanoma. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 14 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991, 96: 689-697.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/12/538/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. We have no personal or financial conflicts of interest related to the preparation and publication of this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

SN was involved in conception and design of the study, interpretation of data, and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakayama, S., Yokote, T., Iwaki, K. et al. A rare case of primary clear cell sarcoma of the pubic bone resembling small round cell tumor: an unusual morphological variant. BMC Cancer 12, 538 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-538

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-12-538