Abstract

Heavy ion storage rings are powerful tools to store and observe key nuclear properties of rare radioactive isotopes. Recent developments in ring physics and enhanced beam intensities have now opened up the possibility to carry out low-energy investigations of nuclear reactions at rings. Pure, intense, exotic beams of isotopes that are otherwise challenging to access can be im**ed on pure, ultra-thin targets, allowing the study of long-standing nuclear astrophysical puzzles in a variety of stellar sites that have so far resisted traditional approaches. In this review paper, we will describe pioneering studies with decelerated beams at the ESR storage ring at GSI (Germany), as well as future exciting prospects at the ESR and CRYRING at GSI/FAIR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Since their emergence in the late eighties and early nineties, heavy ion storage rings have been employed in a wide variety of ground-breaking investigations of nuclear properties involving both stable and radioactive heavy isotopes. In particular, unstable isotopes produced as secondary beams from a rare ion beam (RIB) facility were stored in pioneering experiments. Isotopes orbited the ring for \(\approx \)milliseconds to days, allowing unprecedentedly precise studies of their properties of interest [1]. Due to the limitations and challenges inherent to secondary beam production [2], the early focus was either on mass measurements of exotic nuclei by storing low-intensity fragment mixtures [3], or on investigations of exotic charge states revealing the interplay of atomic and nuclear physics [4, 5]. These groundbreaking experiments were conducted at higher energies, i.e. around or above 100 MeV/u, for reasons of efficient beam production. Years later, the first direct nuclear reaction studies involving an internal target in the ring were conducted at the lower end of this energy range. Initially, high-intensity stable beams of \(^{58}\)Ni were employed [6, 20,21,22]. With the latest improvements in Schottky noise spectroscopy techniques a powerful, non-destructive method of beam monitoring is available [23], which facilitates complex beam manipulations including beam accumulation, local and global orbit manipulations, selective elimination of contaminants and many more [22, 24, 25]. Also, both ESR and CRYRING, have an internal gas jet available providing a variety of ultra-pure, ultra-thin target gases, most prominently hydrogen and helium which are central for the astrophysical studies discussed here [26].

Several exciting challenges related to this novel way to address astrophysical reaction studies in heavy ion storage rings remain to be faced. In particular, storage rings must operate in ultra-high or extreme-high vacuum conditions (UHV/XHV) to enable the measurement of a small nuclear cross section inside the Gamow window, i.e. with stored ions of a few MeV/u or below. In general, storage times of seconds or longer for highly charged ions require a vacuum pressure lower than \(10^{-10}\) mbar, and the absence of high-Z elements in the residual gas. This becomes even more important at lower energies (E < 10 MeV/u), where the cross sections of the atomic processes that dominate beam losses become very large (> kilobarn) [27]. These vacuum requirements pose technical challenges to experimental setups located under vacuum. At higher energies this is usually accomplished using detectors in so called pockets, i.e. behind a stainless steel window acting as a vacuum barrier [28]. These windows can be as thin as 25 \(\upmu \)m, nevertheless heavy ions well below 10 MeV/u will not be able to penetrate with detectable energies [29]. However, nowadays, sophisticated detection systems providing ion energy, hit timing, and position with good resolution and efficiency are commercially available for use in UHV environments. In particular, Double-sided Silicon Strip Detectors (DSSD) are commonly used for ion spectroscopy in low-energy nuclear physics and became available recently featuring low out-gassing materials and in situ bake-out above 100 \(^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) [33].

Significant efforts are ongoing for the development of new storage ring features, vacuum-compatible setups, and detector technology, in order to face the challenges outlined above and improve the reach of these ground-breaking measurement techniques. In the following sections we will outline early pioneering experiments with stable and radioactive beam, as well as planned experiments and future prospects of this exciting new era of low-energy nuclear reaction experiments of astrophysical relevance.

2 Direct measurements of proton-induced radioactive capture reactions at the ESR

The very first experiment with stored ions post-decelerated to about 10 MeV/u was carried out in the ESR in 2008 using a stable beam of \(^{96}\)Ru\(^{44+}\) im**ing on a hydrogen jet [34]. Conceptually the ring served as a luminosity booster and recoil separator for proton-capture reactions. The goal was an absolute measurement of the cross section of the \(^{96}\)Ru(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{97}\)Rh nuclear reaction, via detection of the \(^{97}\)Rh recoils. Detection was facilitated by the negligible momentum carried away by the \(\gamma \) rays in radiative proton-capture reactions involving heavier ions. The recoil cone remained quite narrow and the beam-like \(^{97}\)Rh\(^{45+}\) reaction product ejecta retained approximately the momentum of the stored beam, but had a lower rigidity \(B\rho = p/q\) due to the higher charge state. This enabled separation of the reaction products from the stored beam in the first dipole magnet downstream of the target. DSSDs installed behind the dipole magnet (see Fig. 2) were used to implant the (p,\(\gamma \)) recoils with 100% efficiency providing excellent energy, time and position resolution.

In contrast to inverse kinematic experiments at dedicated low-energy recoil separators or spectrometers, the ions injected into ESR are bare, which is effectively a prerequisite for this measurement approach. The injection energy at about 100 MeV/u or higher enables efficient strip** usually using a carbon stripper foil (\(\approx \) 10 mg/cm\(^2\)). In combination with the relatively thin target this strongly prevents having to deal with complex charge state distributions after the internal target interaction. For stored ions in lower charge states ionization in the target would have to be considered, and would result in beam-like products with very similar \(B\rho \) to those ejecta formed by proton capture. Thus, since the atomic ionization cross sections are several orders of magnitude larger than any nuclear cross section, non-bare ions would render a (p,\(\gamma \)) measurement unfeasible due to the overwhelming atomic background.

In the pilot experiment no UHV detection system was available, instead a pair of common W1-type DSSDs (Micron Semiconductors Ltd. [35]), each 50 \(\times \) 50 mm\(^2\) in size, were employed inside the standard detector pockets at ESR (Fig. 2). A stainless steel entrance window of 25 \(\upmu \)m thickness allowed ions as low as 9 MeV/u to be detected inside the helium filled pocket. Lower energies were not accessible. The measured horizontal position spectrum of ion hits at 11 MeV/u is shown in Fig. 3 against Monte-Carlo simulations. The rather complex background situation with regard to the (p,\(\gamma \)) signature is caused by the relatively high beam energies, which give rise to the competition of four different reaction channels. However, careful simulations of the ion optical system and apertures in ESR as well as the reaction kinematics enabled a disentanglement of the different distributions.

The entire proton-capture measurement is conducted relative to X-ray spectroscopy of the so-called K-REC process, i.e., the radiative component of the capture of a target electron into to the K-shell of the stored ion. For this basic atomic process, which is the inverse of the photo-effect, cross sections can be calculated with high precision for few electron systems [36, 37]. As shown in Fig. 4 cross sections for the \(^{96}\)Ru(p,\(\gamma \)) reaction at 9, 10 and 11 MeV/u could be extracted, providing additional constraints for the production of the p nucleus \(^{96}\)Ru in the \(\gamma \) process, for further details see [34]. Perhaps most importantly, the successful proof-of-concept for this novel low-energy approach led to further developments towards storage ring investigations at even lower energies and with the final goal of an application to RIBs.

The focus in the following years was on upgrading of the detection system to facilitate barrier-free ion implantation in the active material of a detector. This was achieved in 2016, when a new in-vacuum setup was installed at the end of the dipole magnet after the target in ESR (see Fig. 2). It consisted of a single W1 DSSD, for which a UHV package became commercially available a few years earlier [35].

The ion hit distribution measured by the pocket DSSD for \(^{96}\)Ru(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{97}\)Rh at 11 MeV/u in the ESR is shown. Distributions from four different reaction channels had to be considered by Monte-Carlo simulations in order to reproduce the spectrum and extract the proton-capture events. Taken from [34]

The final cross section results of the \(^{96}\)Ru(p,\(\gamma \)) pilot experiment compared to different cross section predictions are shown. Three data points between 9 and 11 MeV provided new constraints for theory. Note, that the normalization based on different measurements of atomic electron capture are compared here. Taken from [34]

Recoil hit distribution of the in-vacuum DSSD for \(^{124}\)Xe\(^{54+}\) incident on a hydrogen jet at 7 MeV/u in the ESR. The narrow cluster of \(^{125}\)Cs ions from proton-capture sits on a broad background of events from Rutherford scattering at the target. Taken from [2).

In a recent beamtime in 2021 this device was taken into operation with an otherwise unmodified setup using again a \(^{124}\)Xe\(^{54+}\) beam. The comparison of (p,\(\gamma \)) data taken with and without the scraper in position revealed a tremendous increase of the signal-to-background ratio by approximately a factor of 10. As will be shown in a forthcoming publication [41], this upgrade leads to an increased sensitivity for the (p,\(\gamma \)) measurement and additionally enables the straightforward extraction of a cross section for the (p,n) reaction channel for \(E_{\text {CM}} > |Q_{\text {(p,n)}}|\).

In the same experiment, the \(^{124}\)Xe primary beam was also used to produce a fragment beam of radioactive \(^{118}\)Te\(^{54+}\) (\(T_{1/2} = 6.0\) d) with the goal to measure the reaction \(^{118}\)Te(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{119}\)I. Analysis of this set of data is ongoing, but we report here on the performance of the ESR in combination with a hot and intense fragment beam from FRS.

Primary beam intensities of about \(3.5 \times 10^9\) could be converted in-flight to fragment injections of about \(3.5 \times 10^5\) pre-separated ions. A production target of \(^{9}\)Be was employed, and the FRS setup was optimized to arrive at 400 MeV/u injection energy to facilitate rapid stochastic cooling of the hot fragment beam [21]. By accumulating up to 20 injections in the ESR the stored intensity reached peak values of \(7 \times 10^6\). Subsequently the fragments were decelerated to about 7 MeV/u and subject to permanent electron cooling [20]. At this final stage an isotopically pure beam with an intensity of about \(1 \times 10^6\) \(^{118}\)Te\(^{52+}\) ions and a lifetime of roughly 2 s could be achieved.

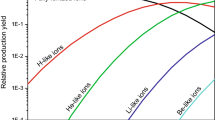

Results of the \(^{124}\)Xe(p,\(\gamma \)) measurement in the ESR. Five absolute cross section values on the high-energy tail of the Gamow window could be extracted. The experimental data set is compared to theory calculations based on different nuclear model input. Taken from [\(^{15}\)O(\(\alpha \),\(\alpha \))\(^{15}\)O nuclear reaction. This is a direct way to measure the alpha widths of the \(^{19}\)Ne nucleus that is formed by the \(^{18}\)F(p,\(\alpha \))\(^{15}\)N reaction which plays a central role in novae explosions [48]. Precise knowledge of the alpha widths is crucial to reduce reaction rate uncertainties [49], but limitations in energy resolutions have hampered investigations. Using electron-cooled radioactive beams at CRYRING (\(\Delta \)E/E \(\simeq \) \(10^{-4}\)) im**ing on the ultra-thin internal target is expected to result in an exceptional energy resolution for this scattering reaction of the order of 1 keV FWHM in the centre-of-mass frame, more than an order of magnitude better than current values [50].

Beam can be injected in the CRYRING from a local ion source independently of the main GSI/FAIR accelerators. This off-line ion source will be used to carry out both commissioning tests and a wide range of scientific investigations for nuclear and atomic physics. While at present the source can only provide stable isotopes there are plans to upgrade it to an EBIT source capable of providing beam of relatively long-lived radioactive isotopes such as e.g. \(^{44}\)Ti (t\(_{1/2}\)=63y) [51]. This radioisotope plays a central role in our understanding of supernova remnants [52], i.e. the radioactive ashes left behind by core-collapse supernovae [53]. Significant uncertainties remain in the destruction rate of \(^{44}\)Ti via the \(^{44}\)Ti(\(\alpha \),p)\(^{47}\)V reaction during the supernova runaway, preventing us from making full use of astronomical observations to constrain our models. Experimental investigations are hampered by the difficulty of producing sufficiently intense \(^{44}\)Ti beams. There are only two datasets available: an upper limit in the supernova Gamow window [54], and a set of data at higher energies [55] for which a re-analysis of published uncertainties was later carried out [56]. Tensions remain between the two datasets [56] and the situation is far from satisfactory. Exploiting the luminosity enhancement thanks to beam recirculation at CRYRING will allow an investigation of this reaction at Gamow energies. Reaction products will be detected with nearly 100% geometric efficiency using the CARME array, thanks to strong kinematic forward focusing.

Indirect studies using techniques such as (d,p) transfer are also planned to be performed at CARME once it will be moved upstream of the internal target. Note that moving CARME requires breaking the vacuum of the CRYRING and returning to XHV, which can take weeks to months [47]. Transfer reactions are very powerful tools [57] to investigate nuclear properties that cannot be otherwise accessed due to e.g. lack of intense radioactive beams, but also properties relating to sub-threshold states or angular distributions that can be difficult to access even with intense beams available. The possibility to use high-quality, high-purity in-flight beams at CRYRING and detect reaction products at extremely small angles with high efficiency, energy and angular resolution using CARME is unprecedented and will open the path to exciting new possibilities. Potentially, a 0 degree system similar to the one described above for the ESR could be used in conjunction with CARME to detect both ejectiles and recoil nuclei, allowing coincidence measurements to be performed.

Finally, the CRYRING is expected to benefit from the installation of a transverse low-energy beamline from the the FISIC project [58]. This will open up a world-unique opportunity for CARME at CRYRING to approach the electron screening problem. Electron screening is a long-standing puzzle [59] that affects all nuclear reactions taking place in quiescent scenarios, including in particular our own Sun. Briefly, nuclear reactions in a laboratory are induced by im**ing a beam ion (that can be fully ionised in principle) on an atomic target nuclei, which always has electrons attached. Electrons surrounding target nuclei shield the Coulomb repulsion between the projectile and the target, enhancing the cross-section. A reliable formalism to model this process is still outside of our grasp [59]. Crossing a fully ionised beam stored in the ring with the fully ionised beam produced by FISIC, will allow the first ever attempt to measure nuclear reactions free of electron screening directly at energies of astrophysical interest. This ground-breaking measurement is expected to take place in the next few years.

The \(\Delta \)E-E measurement for scattered protons at the target is shown for a single strip (64.5°) of the telescope DSSD. The banana shape of the inelastic distribution culminates in an intense peak from the elastic channel. The red contour selects elastic scattering events to infer the experimental resolution. Taken from [66]

4 Neutron induced reactions and the surrogate method with stored ions

Neutron-induced reactions on radioactive nuclei are of crucial importance in nuclear astrophysics. Key nuclear reactions with a strong impact on the element synthesis have been identified for s, r and p processes [13, 60, 61]. The main challenge in measuring these reactions experimentally is the unavailability of a free neutron target, which excludes similar experimental schemes as described in Sects. 2 and 3, as well as most traditional single-pass experiments. The application of RIB techniques to this topical challenge is still at an early stage, in particular with respect to exploiting the advantages of heavy ion storage rings.

Supported by the ERC advanced grant NECTAR, a new project for an experimental campaign aiming to solve this long-standing issue was started at the GSI/FAIR storage rings, with the goal to apply the indirect surrogate technique to infer cross sections of neutron capture and neutron-induced fission [62]. According to the compound nucleus model, the formation and decay of the compound nucleus (CN) system can be treated separately [63], i.e. the exit channel is independent of the entrance one. The experimental approach is to produce the CN state of interest using an alternative nuclear reactions, which does not require a neutron target, in order to study its decay behaviour and improve the predictions of theoretical cross section calculations. The surrogate technique using transfer reactions or inelastic scattering is already established for light beams incident on a heavy target [64, 65]. However, the possibility to study a wide range of astrophysically relevant reactions involving radioactive nuclei becomes available only when employing RIBs.

The vision of this new experimental campaign is to establish surrogate measurements in inverse kinematics using stored, rare and highly-charged ions. It requires a detection scheme that enables the identification of all decay channels of the CN in coincidence with the preceding excitation process. For this purpose the heavy decay products of the CN are implanted in particle detectors positioned according to the reaction kinematics, i.e. in different locations downstream the target. Similar to the proton-capture experiments, this requires bare ions to exclude ionization of beam particles in the target to avoid an overwhelming atomic background. In parallel, the particle ID of light recoil ions from the exciting reaction is extracted from telescope detectors directly at the target.

Heavy ion hit map of the DSSD downstream of the target and dipole magnet in ESR, when in position close to the stored beam. The coincidence condition to scattered protons detected by the telescope at the target is applied and filters events not related the decay of the nuclear compound system. Recoils from the \(\gamma \) decay channel are located close to the detector edge (left bump), the neutron emission signature is clearly separated further away from the beam orbit (central bump). Taken from [66]

Recently, a proof-of-principle experiment for this technique was conducted at the ESR investigating the \(^{207}\)Pb(n,\(\gamma \))\(^{208}\)Pb reaction via the surrogate reaction \(^{208}\)Pb(p,p’) to produce \(^{208}\)Pb* and study its probability to decay by neutron vs. \(\gamma \) emission. A primary beam of \(^{208}\)Pb\(^{82+}\) at 270 MeV/u was stored in ESR and decelerated down to 30 MeV/u. About \(5 \times 10^{7}\) ions were im**ed on the hydrogen target (\(6 \times 10^{13}\) atoms/cm\(^{2}\)), which resulted in a beam lifetime of approximately 25–30 s. A silicon telescope was aligned to 60° at the target, it consisted of a DSSD front layer followed by six 1 mm layers of single-sided, single-area Si detectors with an active area of about \(20 \) mm\(^2\). Additionally, a DSSD with a size of \(122 \times 44\) mm\(^2\) covered inner ring orbits behind the dipole magnet downstream of the target. Thanks to the relatively high beam energies, all particle detectors could be operated in the standard detector pockets of ESR. See [66] for a detailed description of the experiment.

The \(\Delta \)E-E measurement of the proton recoils at the target is shown in Fig. 9 for a single strip of the front DSSD at 64.5°. The expected banana shape of the inelastic scattering distribution overlaps with the intense peak from the elastic channel at high residual energy. The heavy residues of the CN decay were measured by the downstream DSSD, but would usually be concealed by the heavy beam-like partner from elastic scattering. They were revealed by applying the coincidence condition with the inelastic component of the proton distribution at the target. The two extended ion clusters were detected with nearly 100% efficiency, and could be clearly identified and separated, as shown in Fig. 10. The excitation energy of the CN can be reconstructed by making use of the angular resolution of the telescope. This enables a determination of the energy-dependent decay probabilities \(P_n\) and \(P_{\gamma }\) with a resolution of a few 100 keV. In the current setup this resolution is limited by the target diameter \(D \approx 5\) mm.

While the analysis of the data set is ongoing, this proof-of-principle test can be considered accomplished based on the preliminary data analysis presented in [66]. Further development of the technique will focus on an extension to include the detection of the fission channel as well as on a reduced target diameter to improve the energy resolution. The next experiment within NECTAR will use a \(^{238}\)U\(^{92+}\) beam and a deuterium jet target in order to excite the compound systems of \(^{238}\)U* and \(^{239}\)U* via (d,d’) and (d,p), respectively, and study all open decay channels.

5 Conclusion

The study of nuclear cross-sections using low-energy stored beams at heavy ion storage rings is an exciting emerging field in experimental nuclear astrophysics. Modern technologies are now enabling sophisticated, high-precision experiments and novel approaches investigating long standing nuclear puzzles of key importance in a wide variety of astrophysical sites and scenarios. GSI/FAIR has been playing the lead role in pioneering this ground-breaking approach. Direct measurements of nuclear cross sections have been established for proton-induced reactions and RIBs in the ESR, and a number of key reactions for explosive nucleosynthesis are now within reach. CARME is now in operation at the new CRYRING facility with access to the lowest energies needed to cover the Gamow window, and first experiments with stable beams are expected to run soon. Radioactive beam studies will be following soon, and a large variety of topical nuclear reactions will be in focus in the near future. The FISIC project will for the first time enable crossed beam experiments to investigate electron screening effects. Finally, the power of the surrogate technique at storage rings has now been demonstrated experimentally at the ESR with stable beams, and further experiments applying it to radioactive heavy isotopes are planned for the future.

The possibility to carry out these exciting cross-section measurements relies heavily on the availability of intense beams at rings. The performance of the rings themselves, and the possibility to carry out complex beam manipulation operations, such as e.g. beam cooling, are absolutely critical for the success of these experiments and for the delivery of the science programme. Further development of ring capabilities is now required, especially for what concerns the challenges linked to efficient storage of radioactive, short-lived secondary beams.

The remarkable success of storage ring experiments has attracted significant attention at an international level leading to several major international ring projects e.g. at FAIR [67] and HIAF (China) [68]. The interest is particularly high in the low-energy nuclear astrophysics community, where several dedicated low-energy ring projects have been proposed and are in varying states of planning, e.g. at ISOLDE (CERN) and TRIUMF (Canada). In the context, the idea of pairing a free neutron target to a storage ring [69] is being actively pursued in Canada and in the USA [70]. Different approaches are being considered to obtain the necessary neutrons e.g. either from a reactor, or a spallation source, or a commercial neutron generator. The success of this initiative will open up the possibility to directly measure neutron-induced reactions on radioactive isotopes at energies of interest, an extremely significant step forward in the quest of understanding the origin of heavy elements in our Universe.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: All data are listed in the references and are publicly available.]

References

F. Bosch, Y.A. Litvinov, T. Stöhlker, Nuclear physics with unstable ions at storage rings. Progress Part. Nucl. Phys. 73, 84–140 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2013.07.002

H. Geissel, G. Munzenberg, K. Riisager, Secondary exotic nuclear beams. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 45(1), 163–203 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.45.120195.001115

B. Franzke, H. Geissel, G. Münzenberg, Mass and lifetime measurements of exotic nuclei in storage rings. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 27(5), 428–469 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1002/mas.20173

F. Bosch, T. Faestermann, J. Friese, F. Heine, P. Kienle, E. Wefers, K. Zeitelhack, K. Beckert, B. Franzke, O. Klepper, C. Kozhuharov, G. Menzel, R. Moshammer, F. Nolden, H. Reich, B. Schlitt, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, T. Winkler, K. Takahashi, Observation of bound-state \(\beta \)-decay of fully ionized 187Re: 187Re-187Os cosmochronometry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77(26), 5190–5193 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.5190

I. Klaft, S. Borneis, T. Engel, B. Fricke, R. Grieser, G. Huber, T. Kühl, D. Marx, R. Neumann, S. Schröder, P. Seelig, L. Völker, Precision laser spectroscopy of the ground state hyperfine splitting of hydrogen like Bi 8 2 + 209. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73(18), 2425–2427 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.2425

J.C. Zamora, T. Aumann, S. Bagchi, S. Bönig, M. Csatlós, I. Dillmann, C. Dimopoulou, P. Egelhof, V. Eremin, T. Furuno, H. Geissel, R. Gernhäuser, M.N. Harakeh, A.-L. Hartig, S. Ilieva, N. Kalantar-Nayestanaki, O. Kiselev, H. Kollmus, C. Kozhuharov, A. Krasznahorkay, T. Kröll, M. Kuilman, S. Litvinov, Y.A. Litvinov, M. Mahjour-Shafiei, M. Mutterer, D. Nagae, M.A. Najafi, C. Nociforo, F. Nolden, U. Popp, C. Rigollet, S. Roy, C. Scheidenberger, M. von Schmid, M. Steck, B. Streicher, L. Stuhl, M. Thürauf, T. Uesaka, H. Weick, J.S. Winfield, D. Winters, P.J. Woods, T. Yamaguchi, K. Yue, J. Zenihiro, Nuclear-matter radius studies from \(^{58}{\rm ni }(\alpha ,\alpha )\) experiments at the GSI experimental storage ring with the EXL facility. Phys. Rev. C 96(3), 034617 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.96.034617

K. Yue, J.T. Zhang, X.L. Tu, C.J. Shao, H.X. Li, P. Ma, B. Mei, X.C. Chen, Y.Y. Yang, X.Q. Liu, Y.M. **ng, K.H. Fang, X.H. Li, Z.Y. Sun, M. Wang, P. Egelhof, Y.A. Litvinov, K. Blaum, Y.H. Zhang, X.H. Zhou, Measurement of Ni58(p, p)Ni58 elastic scattering at low momentum transfer by using the HIRFL-CSR heavy-ion storage ring. Phys. Rev. C 100(5), 054609 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.100.054609

M.V. Schmid, S. Bagchi, S. Bönig, M. Csatlós, I. Dillmann, C. Dimopoulou, P. Egelhof, V. Eremin, T. Furuno, H. Geissel, R. Gernhäuser, M.N. Harakeh, A.-L. Hartig, S. Ilieva, N. Kalantar-Nayestanaki, O. Kiselev, H. Kollmus, C. Kozhuharov, A. Krasznahorkay, T. Kröll, M. Kuilman, S. Litvinov, Y.A. Litvinov, M. Mahjour-Shafiei, M. Mutterer, D. Nagae, M.A. Najafi, C. Nociforo, F. Nolden, U. Popp, C. Rigollet, S. Roy, C. Scheidenberger, M. Steck, B. Streicher, L. Stuhl, M. Thürauf, T. Uesaka, H. Weick, J.S. Winfield, D. Winters, P.J. Woods, T. Yamaguchi, K. Yue, J.C. Zamora, J. Zenihiro, for the EXL collaboration: Investigation of the nuclear matter distribution of \(^{\rm 56}\)Ni by elastic proton scattering in inverse kinematics. Phys. Scr. T166, 014005 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/2015/T166/014005

GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung. http://www.gsi.de

B. Franzke, The heavy ion storage and cooler ring project ESR at GSI. Nucl. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. B 24, 18–25 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(87)90583-0

M. Lestinsky, V. Andrianov, B. Aurand, V. Bagnoud, D. Bernhardt, H. Beyer, S. Bishop, K. Blaum, A. Bleile, A. Borovik, F. Bosch, C.J. Bostock, C. Brandau, A. Bräuning-Demian, I. Bray, T. Davinson, B. Ebinger, A. Echler, P. Egelhof, A. Ehresmann, M. Engström, C. Enss, N. Ferreira, D. Fischer, A. Fleischmann, E. Förster, S. Fritzsche, R. Geithner, S. Geyer, J. Glorius, K. Göbel, O. Gorda, J. Goullon, P. Grabitz, R. Grisenti, A. Gumberidze, S. Hagmann, M. Heil, A. Heinz, F. Herfurth, R. Heß, P.-M. Hillenbrand, R. Hubele, P. Indelicato, A. Källberg, O. Kester, O. Kiselev, A. Knie, C. Kozhuharov, S. Kraft-Bermuth, T. Kühl, G. Lane, Y.A. Litvinov, D. Liesen, X.W. Ma, R. Märtin, R. Moshammer, A. Müller, S. Namba, P. Neumeyer, T. Nilsson, W. Nörtershäuser, G. Paulus, N. Petridis, M. Reed, R. Reifarth, P. Reiß, J. Rothhardt, R. Sanchez, M.S. Sanjari, S. Schippers, H.T. Schmidt, D. Schneider, P. Scholz, R. Schuch, M. Schulz, V. Shabaev, A. Simonsson, J. Sjöholm, Ö. Skeppstedt, K. Sonnabend, U. Spillmann, K. Stiebing, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, A. Surzhykov, S. Torilov, E. Träbert, M. Trassinelli, S. Trotsenko, X.L. Tu, I. Uschmann, P.M. Walker, G. Weber, D.F.A. Winters, P.J. Woods, H.Y. Zhao, Y.H. Zhang, Physics book: CRYRING@ESR. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2016-02643-6

M. Aliotta, R. Buompane, M. Couder, A. Couture, R.J. deBoer, A. Formicola, L. Gialanella, J. Glorius, G. Imbriani, M. Junker, C. Langer, A. Lennarz, Y.A. Litvinov, W.-P. Liu, M. Lugaro, C. Matei, Z. Meisel, L. Piersanti, R. Reifarth, D. Robertson, A. Simon, O. Straniero, A. Tumino, M. Wiescher, Y. Xu, The status and future of direct nuclear reaction measurements for stellar burning. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 49(1), 010501 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6471/ac2b0f

M. Arnould, S. Goriely, The p-process of stellar nucleosynthesis: astrophysics and nuclear physics status. Phys. Rep. 384(1), 1–84 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(03)00242-4

H. Schatz, K.E. Rehm, X-ray binaries. Nucl. Phys. A 777, 601–622 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.05.200

J. José, M. Hernanz, C. Iliadis, Nucleosynthesis in classical novae. Nucl. Phys. A 777, 550–578 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.02.121

T. Delbar, W. Galster, P. Leleux, I. Licot, E. Liénard, P. Lipnik, M. Loiselet, C. Michotte, G. Ryckewaert, J. Vervier, P. Decrock, M. Huyse, P. Van Duppen, J. Vanhorenbeeck, Investigation of the \(^{13}\)N(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{14}\)O reaction using \(^{13}\)N radioactive ion beams. Phys. Rev. C 48(6), 3088–3096 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.48.3088

C. Akers, A.M. Laird, B.R. Fulton, C. Ruiz, D.W. Bardayan, L. Buchmann, G. Christian, B. Davids, L. Erikson, J. Fallis, U. Hager, D. Hutcheon, L. Martin, A.S.J. Murphy, K. Nelson, A. Spyrou, C. Stanford, D. Ottewell, A. Rojas, Measurement of radiative proton capture on \(^{18}\)F and implications for oxygen-neon novae. Phys. Rev. Lett. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.262502

G. Lotay, G. Christian, C. Ruiz, C. Akers, D.S. Burke, W.N. Catford, A.A. Chen, D. Connolly, B. Davids, J. Fallis, U. Hager, D.A. Hutcheon, A. Mahl, A. Rojas, X. Sun, Direct measurement of the astrophysical \(^{38}\)K(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{39}\)Ca reaction and its influence on the production of nuclides toward the end point of nova nucleosynthesis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116(13), 132701 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.132701

G. Lotay, S.A. Gillespie, M. Williams, T. Rauscher, M. Alcorta, A.M. Amthor, C.A. Andreoiu, D. Baal, G.C. Ball, S.S. Bhattacharjee, H. Behnamian, V. Bildstein, C. Burbadge, W.N. Catford, D.T. Doherty, N.E. Esker, F.H. Garcia, A.B. Garnsworthy, G. Hackman, S. Hallam, K.A. Hudson, S. Jazrawi, E. Kasanda, A.R.L. Kennington, Y.H. Kim, A. Lennarz, R.S. Lubna, C.R. Natzke, N. Nishimura, B. Olaizola, C. Paxman, A. Psaltis, C.E. Svensson, J. Williams, B. Wallis, D. Yates, D. Walter, B. Davids, First direct measurement of an astrophysical p-process reaction cross section using a radioactive ion beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127(11), 112701 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.112701

M. Steck, P. Beller, K. Beckert, B. Franzke, F. Nolden, Electron cooling experiments at the ESR. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 532(1–2), 357–365 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2004.06.065

F. Nolden, K. Beckert, P. Beller, B. Franzke, C. Peschke, M. Steck, Experience and prospects of stochastic cooling of radioactive beams at GSI. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 532(1–2), 329–334 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2004.06.062

M. Steck, Y.A. Litvinov, Heavy-ion storage rings and their use in precision experiments with highly charged ions. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 115, 103811 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2020.103811

M.S. Sanjari, D. Dmytriiev, Y.A. Litvinov, O. Gumenyuk, R. Hess, R. Joseph, S.A. Litvinov, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, A 410 MHz resonant cavity pickup for heavy ion storage rings. Rev. Sci. Int. 91(8), 083303 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0009094

F. Nolden, C. Dimopoulou, R. Grisenti, C.M. Kleffner, S.A. Litvinov, W. Maier, C. Peschke, P. Petri, U. Popp, M. Steck, H. Weick, D.F.A. Winters, T. Ziglasch, radioactive beam accumulation for a storage ring experiment with an internal target. In: Proceedings of 4th International Particle Accelerator Conference, IPAC 2013, May 13–17, 2013, Shanghai, China, p. 3 (2013)

Y.A. Litvinov, S. Bishop, K. Blaum, F. Bosch, C. Brandau, L.X. Chen, I. Dillmann, P. Egelhof, H. Geissel, R.E. Grisenti, S. Hagmann, M. Heil, A. Heinz, N. Kalantar-Nayestanaki, R. Knöbel, C. Kozhuharov, M. Lestinsky, X.W. Ma, T. Nilsson, F. Nolden, A. Ozawa, R. Raabe, M.W. Reed, R. Reifarth, M.S. Sanjari, D. Schneider, H. Simon, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, B.H. Sun, X.L. Tu, T. Uesaka, P.M. Walker, M. Wakasugi, H. Weick, N. Winckler, P.J. Woods, H.S. Xu, T. Yamaguchi, Y. Yamaguchi, Y.H. Zhang, Nuclear physics experiments with ion storage rings. Nucl. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. B 317, 603–616 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.07.025

M. Kühnel, N. Petridis, D.F.A. Winters, U. Popp, R. Dörner, T. Stöhlker, R.E. Grisenti, Low-z internal target from a cryogenically cooled liquid microjet source. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 602(2), 311–314 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.12.212

F.M. Kröger, G. Weber, M.O. Herdrich, J.Glorius, C. Langer, Z. Slavkovská, L. Bott, C. Brandau, B. Brückner, K. Blaum, X. Chen, S. Dababneh, T. Davinson, P.Erbacher, S. Fiebiger, T. Gaßner, K. Göbel, M. Groothuis, A. Gumberidze, G. Gyürky, S. Hagmann, C. Hahn, M. Heil, R. Hess, R. Hensch, P. Hillmann, P.-M. Hillenbrand, O. Hinrichs, B. Jurado, T. Kausch, A. Khodaparast, T. Kisselbach, N. Klapper, C. Kozhuharov, D. Kurtulgil, G. Lane, C. Lederer-Woods, M. Lestinsky, S. Litvinov, Y.A. Litvinov, B. Löher, F. Nolden, N. Petridis, U. Popp, M. Reed, R. Reifarth, M.S. Sanjari, H. Simon, U. Spillmann, M. Steck, J. Stumm, T. Szücs, T.T. Nguyen, A. Taremi Zadeh, B. Thomas, S.Y. Torilov, H. Törnqvist, C. Trageser, S. Trotsenko, M. Volknandt, M. Weigand, C. Wolf, P.J. Woods, V.P. Shevelko, I.Y. Tolstikhina, T. Stöhlker, Electron capture of Xe\(^{54+}\) in collisions with H\(_{2}\) molecules in the energy range between 5.5 and 30.9 MeV/u. Phys. Rev. A 102(4), 042825 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.102.042825

O. Klepper, C. Kozhuharov, Particle detectors for beam diagnosis and for experiments with stable and radioactive ions in the storage-cooler ring ESR. Nucl. Inst. Methods Phys. Res. B 204, 553–556 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-583X(02)02131-6

H. Weick, ATIMA 1.4. https://web-docs.gsi.de/~weick/atima/

J. Glorius, C. Langer, Z. Slavkovská, L. Bott, C. Brandau, B. Brückner, K. Blaum, X. Chen, S. Dababneh, T. Davinson, P. Erbacher, S. Fiebiger, T. Gaßner, K. Göbel, M. Groothuis, A. Gumberidze, G. Gyürky, M. Heil, R. Hess, R. Hensch, P. Hillmann, P.-M. Hillenbrand, O. Hinrichs, B. Jurado, T. Kausch, A. Khodaparast, T. Kisselbach, N. Klapper, C. Kozhuharov, D. Kurtulgil, G. Lane, C. Lederer-Woods, M. Lestinsky, S. Litvinov, Y.A. Litvinov, B. Löher, F. Nolden, N. Petridis, U. Popp, T. Rauscher, M. Reed, R. Reifarth, M.S. Sanjari, D. Savran, H. Simon, U. Spillmann, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, J. Stumm, A. Surzhykov, T. Szücs, T.T. Nguyen, A. Taremi Zadeh, B. Thomas, S.Y. Torilov, H. Törnqvist, M. Träger, C. Trageser, S. Trotsenko, L. Varga, M. Volknandt, H. Weick, M. Weigand, C. Wolf, P.J. Woods, Y.M. **ng, Approaching the Gamow window with stored ions: direct measurement of \(^{124}\)Xe(p,\(\gamma \)) in the ESR storage ring. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122(9), 092701 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.122.092701

A. Henriques, B. Jurado, J. Pibernat, J.C. Thomas, D. Denis-Petit, T. Chiron, L. Gaudefroy, J. Glorius, Y.A. Litvinov, L. Mathieu, V. Méot, R. Pérez-Sánchez, O. Roig, U. Spillmann, B. Thomas, B.A. Thomas, I. Tsekhanovich, L. Varga, Y. **ng, First investigation of the response of solar cells to heavy ions above 1 AMeV. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 969, 163941 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2020.163941

H. Geissel, P. Armbruster, K.H. Behr, A. Brünle, K. Burkard, M. Chen, H. Folger, B. Franczak, H. Keller, O. Klepper, B. Langenbeck, F. Nickel, E. Pfeng, M. Pfützner, E. Roeckl, K. Rykaczewski, I. Schall, D. Schardt, C. Scheidenberger, K.-H. Schmidt, A. Schröter, T. Schwab, K. Sümmerer, M. Weber, G. Münzenberg, T. Brohm, H.-G. Clerc, M. Fauerbach, J.-J. Gaimard, A. Grewe, E. Hanelt, B. Knödler, M. Steiner, B. Voss, J. Weckenmann, C. Ziegler, A. Magel, H. Wollnik, J.P. Dufour, Y. Fujita, D.J. Vieira, B. Sherrill, The GSI projectile fragment separator (FRS): a versatile magnetic system for relativistic heavy ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 70(1–4), 286–297 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-583X(92)95944-M

M. Steck, Recent results from ESR. Phys. Scr. T104(1), 64 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1238/Physica.Topical.104a00064

B. Mei, T. Aumann, S. Bishop, K. Blaum, K. Boretzky, F. Bosch, C. Brandau, H. Bräuning, T. Davinson, I. Dillmann, C. Dimopoulou, O. Ershova, Z. Fülöp, H. Geissel, J. Glorius, G. Gyürky, M. Heil, F. Käppeler, A. Kelic-Heil, C. Kozhuharov, C. Langer, T. Le Bleis, Y. Litvinov, G. Lotay, J. Marganiec, G. Münzenberg, F. Nolden, N. Petridis, R. Plag, U. Popp, G. Rastrepina, R. Reifarth, B. Riese, C. Rigollet, C. Scheidenberger, H. Simon, K. Sonnabend, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, T. Szücs, K. Sümmerer, G. Weber, H. Weick, D. Winters, N. Winters, P. Woods, Q. Zhong, First measurement of the \(^{96}\)Ru(p,\(\gamma \))\(^{97}\)Rh cross section for the p process with a storage ring. Phys. Rev. C (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.92.035803

Micron Semiconductors Ltd. accessed 12/2022. http://www.micronsemiconductor.co.uk

J. Eichler, T. Stöhlker, Radiative electron capture in relativistic ion-atom collisions and the photoelectric effect in hydrogen-like high- Z systems. Phys. Rep. 439(1–2), 1–99 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2006.11.003

A.N. Artemyev, A. Surzhykov, S. Fritzsche, B. Najjari, A.B. Voitkiv, Target effects on the linear polarization of photons emitted in radiative electron capture by heavy ions. Phys. Rev. A 82(2), 022716 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.82.022716

T. Rauscher, Relevant energy ranges for astrophysical reaction rates. Phys. Rev. C (2010). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.81.045807

L. Varga, T. Davinson, J. Glorius, B. Jurado, C. Langer, C. Lederer-Woods, Y.A. Litvinov, R. Reifarth, Z. Slavkovská, T. Stöhlker, P.J. Woods, Y.M. **ng, Towards background-free studies of capture reaction in a heavy-ion storage ring. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1668, 012046 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1668/1/012046

L. Varga, Proton capture measurements on stored ions for the \(\gamma \)-process nucleosynthesis. PhD thesis, University of Heidelberg, Germany (July 2021). https://doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00030259

L. Varga, et al.: Proton-capture studies in the ESR storage rings: measurement of \(^{124}\)Xe(p,\(\gamma \)) and \(^{124}\)Xe(p,n) at improved sensitivity (in preparation)

S.F. Dellmann, J. Glorius, Y.A. Litvinov, R. Reifarth, K.A. Khasawneh, M. Aliotta, L. Bott, B. Brückner, C. Bruno, R. Chen, T. Davinson, T. Dickel, I. Dillmann, D. Dmytriev, P. Erbacher, O. Forstner, H. Geissel, K. Göbel, C.J. Griffin, R. Grisenti, A. Gumberidze, E. Haettner, S. Hagmann, M. Heil, R. Heß, P.-M. Hillenbrand, R. Joseph, B. Jurado, C. Kozhuharov, I. Kulikov, B. Löher, C. Langer, G. Leckenby, C. Lederer-Woods, M. Lestinsky, S. Litvinov, B.A. Lorenz, E. Lorenz, J. Marsh, Menz, T. Morgenroth, N. Petridis, J. Pibernat, U. Popp, T. Psaltis, S. Sanjari, C. Scheidenberger, M. Sguazzin, R.S. Sidhu, U. Spillmann, M. Steck, T. Stöhlker, A. Surzhykov, J. Swartz, H. Törnqvist, L. Varga, H. Weick, M. Weigand, P. Woods, Y. **ng, T. Yamaguchi, Proton capture on stored radioactive \(^{118}\)Te ions. EPJ Web Conf. 279, 11018 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202327911018

T. Rauscher, N. Nishimura, R. Hirschi, G. Cescutti, A.S.J. Murphy, A. Heger, Uncertainties in the production of p nuclei in massive stars obtained from Monte Carlo variations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 463(4), 4153–4166 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stw2266

N. Nishimura, T. Rauscher, R. Hirschi, A.S.J. Murphy, G. Cescutti, C. Travaglio, Uncertainties in the production of p nuclides in thermonuclear supernovae determined by Monte Carlo variations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 474(3), 3133–3139 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stx3033

M. Lugaro, M. Pignatari, U. Ott, K. Zuber, C. Travaglio, G. Gyürky, Z. Fülöp, Origin of the p-process radionuclides \(^92 {\rm Nb} and ^{\rm 146}\)Sm in the early solar system and inferences on the birth of the Sun. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113(4), 907–912 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1519344113

C. Travaglio, R. Gallino, T. Rauscher, N. Dauphas, F.K. Röpke, W. Hillebrandt, Radiogenic p-isotopes from type Ia supernova, nuclear physics uncertainties, and galactic chemical evolution compared with values in primitive meteorites. Astrophys. J. 795(2), 141 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/795/2/141

C.G. Bruno et al., CARME, the carrying array for reaction measurement. Nucl. Instrum. Methods A 1048, 168007 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2022.168007

J. Jose, Stellar Explosions: Hydrodynamics and Nucleosynthesis (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1201/b19165

D. Kahl, J. José, P.J. Woods, Uncertainties in the \(^{18}\)F(p,\(\alpha \)) reaction rate in classical novae. A &A 653, 64 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140339

D. Torresi, C. Wheldon, T. Kokalova, S. Bailey, A. Boiano, C. Boiano, M. Fisichella, M. Mazzocco, C. Parascandolo, D. Pierroutsakou, E. Strano, M. Zadro, M. Cavallaro, S. Cherubini, N. Curtis, A. Di Pietro, J.P. Fernández Garcia, P. Figuera, T. Glodariu, J. Gr ȩ bosz, M. La Cognata, M. La Commara, M. Lattuada, D. Mengoni, R.G. Pizzone, C. Signorini, C. Stefanini, L. Stroe, C. Spitaleri, Evidence for \(^{15}\) O+\(\alpha \) resonance structures in \(^{19}\) Ne via direct measurement. Phys. Rev. C 96, 044317 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.96.044317

O. Forstner, D. Bemmerer, T.E. Cowan, R. Dressler, A.R. Junghans, D. Schumann, T. Stöhlker, T. Szücs, A. Wagner, K. Zuber, Opportunities for measurements of astrophysical-relevant alpha-capture reaction rates at cryring@esr. X-Ray Spectrom. 49(1), 129–132 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/xrs.3071

D.D. Clayton, L. **, B.S. Meyer et al., Nuclear reactions governing the nucleosynthesis of 44Ti. Astrophys. J. 504(1), 500 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1086/306057

B. Grefenstette, F. Harrison, S. Boggs, S. Reynolds, C. Fryer, K. Madsen, D.R. Wik, A. Zoglauer, C. Ellinger, D. Alexander et al., Asymmetries in core-collapse supernovae from maps of radioactive 44Ti in Cassiopeia A. Nature 506(7488), 339–342 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12997

V. Margerin, A.S.J. Murphy, T. Davinson, R. Dressler, J. Fallis, A. Kankainen, A. Laird, G. Lotay, D. Mountford, C. Murphy et al., Study of the \(^{44}\)Ti(\(\alpha \), p)\(^{47}\)V reaction and implications for core collapse supernovae. Phys. Lett. B 731, 358–361 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2014.03.003

A. Sonzogni, K. Rehm, I. Ahmad, F. Borasi, D. Bowers, F. Brumwell, J. Caggiano, C. Davids, J. Greene, B. Harss et al., The \(^{44}\)Ti(\(\alpha \), p) reaction and its implication on the \(^{44}\)Ti yield in supernovae. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84(8), 1651 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1651

K.A. Chipps, P. Adsley, M. Couder, W.R. Hix, Z. Meisel, K. Schmidt, Evaluation of experimental constraints on the \(^{44}\)Ti(\(\alpha \), p)\(^{47}\)V reaction cross section relevant for supernovae. Phys. Rev. C 102(3), 035806 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.102.035806

V. Margerin, G. Lotay, P. Woods, M. Aliotta, G. Christian, B. Davids, T. Davinson, D. Doherty, J. Fallis, D. Howell et al., Inverse kinematic study of the \(^{26g}\)Al(d, p)\(^{27}\)Al reaction and implications for destruction of \(^{26}\)Al in wolf-rayet and asymptotic giant branch stars. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115(6), 062701 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.062701

D. Schury, A. Méry, J.M. Ramillon, L. Adoui, J.-Y. Chesnel, A. Lévy, S. Macé, C. Prigent, J. Rangama, P. Rousseau, S. Steydli, M. Trassinelli, D. Vernhet, A. Gumberidze, T. Stöhlker, A. Bräuning-Demian, C. Hahn, U. Spillmann, E. Lamour, The low energy beamline of the fisic experiment: current status of construction and performance. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1412(16), 162011 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1412/16/162011

M. Aliotta, K. Langanke, Screening effects in stars and in the laboratory. Front. Phys. (2022). https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2022.942726

F. Käppeler, R. Gallino, S. Bisterzo, W. Aoki, The \(s\) process: nuclear physics, stellar models, and observations. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 157–193 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.83.157

F.-K. Thielemann, D. Mocelj, I. Panov, E. Kolbe, T. Rauscher, K.-L. Kratz, K. Farouqi, B. Pfeiffer, G. Martinez-Pinedo, A. Kelic, K. Langanke, K.-H. Schmidt, N. Zinner, The r-process: supernovae and other sources of the heaviest elements. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 16(04), 1149–1163 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301307006587

A. Henriques, B. Jurado, M. Grieser, D. Denis-Petit, T. Chiron, L. Gaudefroy, J. Glorius, C. Langer, Y.A. Litvinov, L. Mathieu, V. Méot, R. Pérez-Sánchez, J. Pibernat, R. Reifarth, O. Roig, B. Thomas, B.A. Thomas, J.C. Thomas, I. Tsekhanovich, Indirect measurements of neutron cross-sections at heavy-ion storage rings. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1668(1), 012019 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1668/1/012019

N. Bohr, Neutron capture and nuclear constitution. Nature 137(3461), 344–348 (1936). https://doi.org/10.1038/137344a0

J.E. Escher, J.T. Harke, F.S. Dietrich, N.D. Scielzo, I.J. Thompson, W. Younes, Compound-nuclear reaction cross sections from surrogate measurements. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84(1), 353–397 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.84.353

R. Pérez Sánchez, B. Jurado, V. Méot, O. Roig, M. Dupuis, O. Bouland, D. Denis-Petit, P. Marini, L. Mathieu, I. Tsekhanovich, M. Aïche, L. Audouin, C. Cannes, S. Czajkowski, S. Delpech, A. Görgen, M. Guttormsen, A. Henriques, G. Kessedjian, K. Nishio, D. Ramos, S. Siem, F. Zeiser, Simultaneous determination of neutron-induced fission and radiative capture cross sections from decay probabilities obtained with a surrogate reaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125(12), 122502 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.122502

M. Sguazzin, et al.: Determining neutron-induced reaction cross sections through surrogate reactions at storage rings. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. (under review, 2022)

FAIR technical design report, GSI, Darmstadt (2008). https://fair-center.eu

J.C. Yang, J.W. **a, G.Q. **ao, H.S. Xu, H.W. Zhao, X.H. Zhou, X.W. Ma, Y. He, L.Z. Ma, D.Q. Gao, J. Meng, Z. Xu, R.S. Mao, W. Zhang, Y.Y. Wang, L.T. Sun, Y.J. Yuan, P. Yuan, W.L. Zhan, J. Shi, W.P. Chai, D.Y. Yin, P. Li, J. Li, L.J. Mao, J.Q. Zhang, L.N. Sheng, High intensity heavy ion accelerator facility (HIAF) in China. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 317, 263–265 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.08.046

R. Reifarth, Y.A. Litvinov, Measurements of neutron-induced reactions in inverse kinematics. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams 17, 014701 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.17.014701

North American storage ring and neutron capture workshop (2021). https://meetings.triumf.ca/event/235/

Acknowledgements

J.G. gratefully acknowledges support by the State of Hesse within the Research Cluster ELEMENTS (Project ID 500/10.006). C.G.B. is supported by the ELDAR (burning questions on the origin of the Elements in the Lives and Deaths of stARs) UKRI ERC StG (EP/X019381/1). The publication is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - 491382106 , and by the Open Access Publishing Fund of GSI Helmholtzzentrum fuer Schwerionenforschung.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by Nicolas Alamanos.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glorius, J., Bruno, C.G. Low-energy nuclear reactions with stored ions: a new era of astrophysical experiments at heavy ion storage rings. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 81 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00985-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00985-x