Abstract

Prior research has shown that CEO narcissism can significantly impact firms’ strategic decision-making and performance. Additionally, studies on cross-boundary growth have demonstrated its positive effect on firms’ financial performance. However, little is known about the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth. In this study, we integrate upper echelon theory and agency theory and propose that CEO narcissism has a positive effect on a firms’ cross-boundary growth, both domestically and internationally. Furthermore, different types of corporate ownership and ownership concentration have varying effects on this relationship. Our research analyzed publicly listed manufacturing firms in China from 2005 to 2014 and found supportive evidence for our hypotheses. This study offers insight into how micro factors, such as CEO narcissism, can affect a firms’ growth strategy. Our study further sheds light on the differentiating role of corporate ownership and ownership concertation in affecting this relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With an increasingly competitive business environment, more and more firms are engaging in cross-boundary growth to ensure business survival and achieve sustainable growth. The concept of cross-boundary growth first appeared in the Edsel Automobile advertising magazine launched by Ford in 1957. Originally, it meant “transformation,” but now it has been extended to include “boundary spanning” and “crossover development” in new business models, markets, and locations (Birkinshaw et al., 2017; Goerzen, 2018; Schotter et al., 2017; Zott et al., 2011). For instance, Alibaba expanded their e-commerce to include other areas such as insurance and financial management (**e et al., 2021), **aomi moved from their initial business in television and agriculture to smartphone design and production (Lu, 2017), and Starbucks and Haier have grown their businesses around the world (Liu & Li, 2002; Patterson, 2010). These examples demonstrate that firms’ growth beyond their original boundaries could significantly enhance their market positions. While a firm’s economic or financial growth refers to increases in the firms’ revenue and profits (Beck et al., 2008), cross-boundary growth mainly refers to the expansion of business activities (Birkinshaw et al., 2017; Goerzen, 2018; Schotter et al., 2017; Zott et al., 2011). Empirical research has found that firms’ cross-boundary growth has a positive impact on their financial performance (Dubofsky & Varadarajan, 1987; Kaufmann & Tödtling, 2001).

Narcissism is a personality trait that combines grandiosity, attention-seeking, an inflated self-view, and a lack of regard for others (Cragun et al., 2020; Rosenthal & Pittinsky, 2006). Many business leaders, such as Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, have been called narcissists (Maccoby, 2000; Sharma & Grant, 2011). Senior managers such as CEOs are found to have a high prevalence of narcissism (Kohut, 2009). The influence of CEO narcissism on firms’ strategic decision-making and performance is well-documented, exhibiting both positive and negative implications. Narcissistic CEOs, through risk-taking and charisma, can spur innovation and inspire stakeholders, boosting strategic performance (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007; Gerstner et al., 2013; Zhu & Chen, 2015b). However, their boldness may lead to excessive risk-taking and a potentially toxic environment, which may harm employee morale and increase turnover rates (Chatterjee & Pollock, 2017; O’Reilly et al., 2014; Resick et.al., 2009). Recognizing these conflicting impacts, it becomes crucial to understand the role of CEO narcissism in cross-boundary growth of firms. Our study is thus motivated to shed light on how this personal characteristic shapes a firm’s growth strategies and identify possible moderating factors in this relationship. Consequently, our study, inspired to explore this relationship and enriched by the integration of upper echelons theory and agency theory, aims to deepen our understanding of strategic decision-making processes.

Integrating the research in firms’ cross-border research, our study categorizes cross-boundary growth into two types: cross-border growth and cross-functional growth. Cross-border growth refers to whether the firm has expanded its business across countries (Ramaswamy et al., 1996; Zahra et al., 2000). Cross-functional growth refers to whether the firm has integrated the upstream and downstream of its value chain domestically (Troy et al., 2008; Vad Baunsgaard & Clegg, 2013). By clarifying these two growth types, our study offers a more detailed understanding of CEO narcissism’s impact on both cross-border and cross-functional growth. Using a sample of publicly listed manufacturing companies in China from 2005 to 2014, the study finds positive relationships between CEO narcissism and both types of cross-boundary growth.

Additionally, aligning with Cragun et al. (2020) recommendation, this study considers the contextual influence of corporate governance on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ strategy. Corporate governance, widely studied for its impact on strategic decision-making and performance (Chakraborty et al., 2019; Daily et al., 2003; Sheikh, 2019), is introduced here through two aspects—corporate ownership and ownership concentration (Claessens & Yurtoglu, 2013; Young et al., 2008). These serve as potential moderators for the relationship between CEO narcissism and cross-boundary growth. Corporate ownership is defined as the legal possession of a business, signifying the entities responsible for business control and operations. (Ahmad & Omar, 2016). Ownership concentration indicates the degree of power shareholders have in influencing firms’ decision-making process and functions as an external control for firms’ strategic decision-making (Li et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). According to agency theory, high ownership concentration means that major shareholders have controlling power and it functions as counterbalance power to the top leadership in the firm (Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Liu et al., 2011). The study investigates the influence of corporate ownership and ownership concentration on the correlation between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth. Findings suggest that these aspects of corporate governance moderate the relationship between CEO narcissism and the two types of cross-boundary growth—cross-border and cross-functional—in distinct ways.

Our study offers several contributions. Firstly, we address the need for a deeper understanding of the impact of CEO narcissism on firms’ cross-boundary growth, contributing to a more nuanced comprehension of the drivers of firm growth by considering micro factors. Secondly, our study contributes to the existing knowledge by identifying and investigating the impact of CEO narcissism on two distinct dimensions of cross-boundary growth: geographic expansion and functional development. By considering both aspects, we provide a more comprehensive understanding of how CEO narcissism influences firms’ growth in terms of expanding into new markets and venturing into different business domains. Lastly, by examining the moderating role of corporate ownership and ownership concentration, we refine the model and highlight the contingent nature of the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth based on corporate governance features, adding nuance to our analysis.

Literature review and hypotheses

Theoretical background

According to early organizational scholars, organizational decisions are thought to be influenced more by leaders’ personality and behavior than by a mechanical quest for economic optimization (Cyert & March, 1963; March & Simon, 1958). March and Simon (1958) suggested that decision makers bring their own knowledge, values, and beliefs to an organization’s strategic decision-making process. In their upper echelon theory, Hambrick and Mason (1984) emphasized that upper echelon characteristics, such as the personality and values of powerful managers and shareholders, have a significant impact on an organization’s strategic choices. A common personality examined in the upper echelon literature is narcissism. Narcissism refers to a personality trait with which an individual has an inflated view of themselves and longs for power and admiration (Campbell, 1999; Raskin & Terry, 1988). Although related to overconfidence, narcissism is more stable. Overconfidence is the overestimation of one’s actual ability, performance, level of control, or chance of success (Moore & Healy, 2008). Overconfidence is a type of cognitive bias, whereas narcissism is a personality trait that describes both cognition and behavior: “Narcissism is a quality of the self that has significant implications for thinking, feeling, and behaving” (Campbell & Foster, 2007, p. 12). Existing studies have shown that narcissistic CEOs, due to self-interest, risk-taking, and overconfidence, tend to pursue acquisitions, innovation, and capital expenditures (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2011; Gerstner et al., 2013; Patel & Cooper, 2014; Resick et al., 2009; Wales et al., 2013; Zhu & Chen, 2015b).

Agency theory provides a theoretical foundation to explore the link between CEO narcissism and firms’ strategic decision-making. This theory suggests that due to the separation between corporate ownership and governance, professional managers, acting as agents, might prioritize their own interests over shareholders’, especially when faced with complex and conflicting strategic decisions (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). Narcissistic CEOs, as documented by Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007), exhibit an amplified degree of this self-interested decision-making. Narcissism is comprised of cognitive and motivational components (Campbell & Miller, 2011). Cognitively, narcissists hold inflated self-views, believing themselves to be exceptionally talented and possessing superior qualities like wisdom and leadership (John & Robins, 1994; Judge et al., 2006). This self-confidence fosters unwavering trust in their abilities and judgments, especially within their domains of expertise (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007; Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998). Motivationally, narcissists are driven to showcase their supremacy to receive external validation and acclaim (Campbell, 1999; Morf & Rhodewalt, 2001).

Supporting these theoretical claims, Agnihotri and Bhattacharya (2021) found that narcissistic CEOs favor investment projects and mergers and acquisitions that satisfy their personal desires and attract public attention. Moreover, during adversity, narcissistic leaders can inspire followers with their confident vision of overcoming challenges (Maccoby, 2000). O’Reilly and Chatman (2020) demonstrated that narcissists’ behaviors and strategies, fueled by self-confidence and a willingness to take risks, are particularly appealing in disruptive and uncertain times. The findings presented in the existing research underscore the impact of narcissistic CEOs, acting in their capacity as agents, on the strategic decision-making of firms. Their distinct cognitive and motivational traits determine how they rank interests, evaluate their abilities, respond to crises, and ultimately, guide the company’s strategic path.

Hypotheses development

CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-border growth

According to organizational scholars, cross-boundary growth refers to firms’ business activities that move beyond organizational boundaries (Rosenkopf & Nerkar, 2001). These activities may involve growth across different business models, market fields, and locations (Goerzen, 2018; Schotter et al., 2017; Zott et al., 2011). To sustain development and competitive advantage, firms need to integrate various sources of knowledge and expertise obtained beyond their organizational boundaries and implement them in their products and services (Macpherson & Holt, 2007; Palich et al., 2000). Research shows that when there is a good fit with a firm’s strategic vision, cross-boundary growth has a positive impact on inter-firm collaboration, business model innovation, and financial performance (Birkinshaw et al., 2017; Rosenkopf & Nerkar, 2001; Schommer et al., 2019).

While prior research has focused on how organizational factors such as resources, board compositions, and networks, as well as macro factors such as task environment, industrial competitiveness, and institutional environment, affect cross-boundary growth (Du & Boateng, 2015; Hitt et al., 2006; Li et al., 2012), less is known about how micro factors such as CEO narcissism, might affect it. Our study classifies cross-boundary growth into two types: cross-border growth and cross-functional growth. Cross-border growth refers to a strategic behavior of firms in expanding their business beyond their home country to other countries (Ramaswamy et al., 1996; Zahra et al., 2000). This growth strategy has been observed among firms in emerging markets such as China and India (De Beule & Duanmu, 2012; Deng, 2012; Yang et al., 2009).

We propose that CEO narcissism has a positive relationship with cross-border growth. The full theoretical model is shown in Fig. 1. Li and Tang (2010) showed that narcissistic CEOs of Chinese firms have a greater propensity to take risks. Narcissistic CEOs tend to feel good about themselves and are willing to accept challenges and explore new market environments to gain a competitive position and demonstrate their superior ability. Zhang et al. (2017a, 2017b) also found that narcissistic CEOs tend to take a radical exploration approach to gain stakeholder and public attention. Cross-border growth involves a high level of risk. When a firm expands cross-border, it is likely that it will face the liability of foreignness and unfamiliarity with political, economic, and cultural environments (Zaheer, 1995; Zhou & Guillen, 2016). The increased psychic and geographical distances increase the risk and uncertainty for international expansion (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009; Oesterle et al., 2016). Research shows that with international experience, CEOs’ risk-taking propensity increases, resulting in high-risk strategic decisions such as acquisitions and internationalization (Nadkarni & Herrmann, 2010; Tihanyi et al., 2000). Even without previous international experience, firms with narcissistic CEOs are also likely to pursue internationalization (Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, 2019; Oesterle et al., 2016). For firms located in emerging markets such as China, cross-border expansion requires a higher level of confidence and risk-taking propensity, both of which are possessed by narcissistic CEOs. Therefore, we propose:

H1a

CEO narcissism has a positive relationship with firms’ cross-border growth.

CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-functional growth

Cross-functional growth refers to a domestic growth strategy for firms, which involves increased integration of elements upstream and downstream in the value chain (Baunsgaard & Clegg, 2013; Troy et al., 2008). Research has shown that cross-functional integration can enhance innovation and competitiveness (Leenders & Wierenga, 2002; Song et al., 1997). Firms typically engage in different activities within the value chain, such as research, design, production, sales, logistics, and service (Kaplinsky & Morris, 2000; Porter, 1985). They involve in cross-functional development when they combine different activities, such as manufacturing, logistics, marketing, and services (Kim et al., 2001).

While a typical manufacturing firm focuses on designing and producing products (Ulrich, 1995), some narcissistic CEOs may believe that their firms can do more than just manufacturing products. They tend to believe that cross-functional growth can provide a competitive advantage in the value chain, and that their knowledge and expertise accumulated over time can give them a first-mover advantage over competitors. Research has shown that narcissistic CEOs adopt radical technologies (Gerstner et al., 2013) and make excessive investments in mergers and acquisitions (Ham et al., 2018). They also exercise strong supervision and control over the organization and its members (Kim et al., 2001), and may promote vertical integration within the firm to capture more value in the value chain. Therefore, we propose the following:

H1b

CEO narcissism has a positive relationship with firms’ cross-functional growth.

Moderating role of corporate ownership

Corporate ownership refers to the legal ownership of a business that determines who is responsible for controlling and operating the business (Ahmad & Omar, 2016). According to agency theory, managers tend to take risks and pursue business diversification, even if it threatens the returns to shareholders, because they act as agents (Denis et al., 1999). Narcissistic CEOs tend to have a positive interpretation of their past experiences to maintain their inflated self-esteem (Campbell, 1999). They also tend to believe that they have a better understanding of the firm’s strategy (Farwell & Wohlwend-Lloyd, 1998; John & Robins, 1994). However, different types of corporate ownership have different access to resources and different approaches to business operation and decision-making (Baysinger et al., 1991), which may affect the influence of narcissistic CEOs on firms’ cross-boundary growth.

In emerging markets and Asian countries, there is a mixture of different types of corporate ownership, including SOEs, non-SOEs such as private enterprises and foreign enterprises (Chen et al., 2006; Garnaut et al., 2005; Lemmon & Lins, 2003; Luo & Junkunc, 2008). SOEs are legal entities that undertake commercial activities on behalf of the government (Garnaut et al., 2005). Because non-SOEs are either privately funded or funded by foreign capital, their primary focus is on exploiting business opportunities to maximize profits (Ding et al., 2007; Garnaut et al., 2005). However, given the nature of different types of ownership, we propose that the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth is contingent on corporate ownership. The positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth is likely to be weakened for firms with SOE ownership. First, SOEs have a centralized decision-making style and privileged access to resources and markets (Du & Boateng, 2015; Zhang et al., 2017a, 2017b). Second, compared with non-SOEs, SOEs demonstrate a lower level of entrepreneurial orientation and risk-taking (Hunt, 2021). Thus, given the high risk involved in cross-border growth, SOEs are less likely than non-SOEs to pursue cross-border growth. However, given the privilege of resource and market access domestically, SOEs are more likely to engage in cross-functional growth domestically. Therefore, we propose that the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth is moderated by corporate ownership, specifically:

H2a

Compared with non-SOEs, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-border growth is weaker for firms with SOE ownership.

H2b

Compared with non-SOEs, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-functional growth is stronger for firms with SOE ownership.

Moderating role of ownership concentration

Ownership concentration refers to the composition of the board of directors and the degree of power that shareholders have in influencing corporate decision-making (Li et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2011). High ownership concentration highlights the presence of large and controlling shareholders. According to agency theory, for firms with high ownership concentration, key shareholders can timely and effectively monitor operation and management, alleviate agency costs and opportunistic behaviors, and consequently improve firm performance (Blair, 1996; Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). Studies have shown that, with high ownership concentration, major shareholders intervene in firms’ decision-making and business operations and limit the power and ability of managers (Porta et al., 1999). For example, in the Anglo-American context, a more decentralized ownership structure develops a strong external monitoring mechanism, whereas in Japan and Germany, more concentrated ownership concentration corresponds to a strong internal monitoring mechanism (Ahmad & Omar, 2016).

Yang’s (2014) study also showed that ownership concentration has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between the heterogeneity of the top management team and firms’ entrepreneurial orientation. In contrast, when a firm has low monitoring capacity from shareholders and the board of directors, it is more likely to pursue risky diversification (Fuente & Velasco, 2019). Thus, we propose that the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and the firms’ cross-boundary growth will be moderated by ownership concentration. For example, for firms with a high level of ownership concentration, shareholders may have more influence on CEOs’ decision-making, and thus they are more likely to prevent narcissistic CEOs from taking a risky growth approach. Therefore, we propose that the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and the firms’ cross-boundary growth is moderated by ownership concentration, more specifically:

H3a

Compared with firms with high ownership concentration, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-border growth is weaker for firms with high ownership concentration.

H3b

Compared with firms with high ownership concentration, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-functional growth is weaker for firms with high ownership concentration.

Methodology

Data and sample

This study selected Chinese publicly listed manufacturing firms as research samples. Collecting data on CEOs of listed companies is often viewed as difficult, especially for sensitive topics such as narcissism. To build our dataset, we accessed archival data from various sources. Information on CEOs, including age, gender, education background, and level of narcissism, was collected from the Wind database, company websites, major financial news, and media interviews (e.g., interviews published in reputable media such as Sina Finance, Character Column, Economics Weekly). Information on firms, such as their cross-boundary growth, corporate governance, age, size, and financial leverage, as well as independent directors, was collected from company annual reports, authoritative data source Wind database, and CSMAR (Liang et al., 2015; Zhang & Qu, 2016).

During the research design, we attempted to collect up-to-date data, but collecting information on all independent, dependent, moderation, and control variables systematically was a challenge for this study. Some information for certain variables was not available for recent years. Thus, we followed previous empirical research (Yang et al., 2015; Zhu et al., 2020) by choosing a ten-year time window for our sample, which comprises systematic information on these variables. We compiled a dataset covering Chinese manufacturing companies listed on the stock exchange for the period from 2005 to 2014. By the end of 2014, the manufacturing industry in China had 1659 listed companies. Following the ideas and methods from extant research (Wales et al., 2013; Zhu & Chen, 2015a, 2015b), we applied the following screening criteria to form our sample: (1) the years of service of the CEOs of the sample firms should fall within the specified time range, and they should have held their posts in their enterprises for at least four years; (2) these firms should disclose full information about the relevant variables, including the variables for measuring CEO narcissism (e.g., company news, character interviews, and speeches), firms’ cross-boundary (i.e., cross-border and cross-functional) growth, among others. After applying these screening criteria, our sample comprised 252 CEOs from 245 listed companies.

Variable measurement

Independent variable: CEO narcissism

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, CEOs of publicly listed companies are generally unwilling to participate in surveys. Therefore, our research used unobtrusive indicators of personality to measure CEO narcissism (Peterson et al., 2003). To measure CEO narcissism, we followed the measurement suggested by Emmons (1987) and Chatterjee and Hambrick (2007, 2011), which we adjusted to suit our research context. Specifically, we measured CEO narcissism based on the following indicators: (1) the proportion of news about and speeches by the CEO posted on the company website; (2) the proportion of CEOs who use first-person language (e.g., “I,” “myself,” and “my own”) in their speeches and media interviews; and (3) the salary gap between the CEO and the second-highest paid senior manager. We captured all this information when the CEO was in the second and third year of their tenure. The size of the photo is another index of CEO narcissism (Chatterjee & Hambrick, 2007, 2011). However, since the photos of CEOs and other managers are usually not shown in the annual reports of listed companies in China, we excluded this indicator.

The results show a high correlation between these three indicators of CEO narcissism, with Pearson correlation coefficients of 0.812, 0.397, and 0.329, respectively. We also tested the reliability of the three indexes, with Cronbach’s α value of 0.756, which is higher than the minimum acceptable value of 0.65. Furthermore, we conducted a factor analysis and found that these three indicators can be aggregated by one indicator, with a variance explanation ratio of 68.69% and factor loading of 0.925, 0.902, and 0.626, respectively. Thus, to reduce complexity and facilitate analysis, we followed the approach of Zhu and Chen (2015a) and Wen et al. (2015) in measuring CEO narcissism. Specifically, we standardized the three indicators and took the arithmetic mean for the CEO’s narcissism score. The higher the score, the higher the degree of narcissism.

Dependent variable: firms’ cross-boundary growth

Cross-border growth is measured by the proportion of overseas sales revenue in the total sales revenue of the sample companies at the end of the year.

Cross-functional growth was measured using the value-added method (VAS) (Adelman, 1955). The VAS method measures the degree of vertical integration of the firm by calculating the increase of added value against other financial indices. The specific formula is as follows:

Net assets are equal to total assets minus total liabilities, while value added is equal to sales revenue minus cost of sales. To collect information on “sales volume,” “cost of sales,” and “net profit after tax,” we looked at “business income,” “main business cost,” and “net profit” in the annual report of sample firms. We also gathered information on “average return on equity,” which measures the amount of net income compared to the average shareholders’ equity of a company, from the annual reports.

Moderating variables

Corporate ownership. Our study distinguishes between two types of corporate ownership based on existing literature: state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs). A company is classified as an SOE (with a value equal to 1) if the government owns more than 50% of the company and as a non-SOE (with a value equal to 0) if an individual or other type of organization owns more than 50% of the company, such as private holding, foreign holding, social organization holding, or employee association holding. There are 82 SOEs and 163 non-SOEs in our sample.

Ownership concentration. This variable is measured by the shareholding ratio of the top ten shareholders at the end of the year for the sample firm. Generally, higher ratios indicate higher ownership concentration.

Control variables

We controlled for variables at three different levels. First, to account for individual-level factors that might influence narcissism, we controlled for CEO age, gender, and educational background. CEO age is measured as the length of time between the CEO’s birth and the time at which the sample firm was studied. CEO gender is captured as a dummy variable equal to “1” if the CEO is female and “0” otherwise. CEO education background is a dummy variable equal to “1” if the CEO has a bachelor’s degree or above and “0” otherwise. Next, we controlled for firm-level variables that might have a compound effect on the relationship we investigated. These variables included firm size, age, leverage, and proportion of independent directors. Firm age is measured as the number of years of a firm’s financial data available in the database prior to the firm’s fiscal year-end. Firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of the book value of total assets at the end of the year. Leverage is measured by the ratio of total liabilities to total assets of the sample company at the end of the year. Proportion of independent directors is measured by the proportion of independent directors on the board of directors of sample companies. Finally, we controlled for the feature of the external environment, which might also affect firms’ growth strategies. The Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies (2012 Revision) classified 29 manufacturing industry segments. Following existing research, we differentiated two types of industrial environment: stable and dynamic. Stable industrial environment (with a value equal to 0) refers to the industrial condition that is relatively constant and predictable. In our sample, this is represented by 142 companies, covering production in agriculture and sideline products, food, textile, and furniture, among others. Dynamic industrial environment (with a value equal to 1) refers to the industrial condition that constantly changes, requiring adaptation and flexibility in response to new circumstances. It is represented by 103 firms, covering manufacturing in pharmaceuticals products, computer, communication, and other electronic equipment manufacturing, among others.

Results

Descriptive statistics and hypothesis testing

Table 1 presents brief information about CEO profiles and characteristics of firms. Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlation matrix for all the variables. As shown in Table 2, there is a significant relationship between CEO narcissism, corporate governance (including corporate ownership and ownership concentration), and cross-boundary growth of firms. The correlation coefficients of the independent variables are all lower than 0.40, the eigenvalue of the independent variables is not equal to 0, the condition index value is less than 30, and the inflation factor (VIF) is less than 10. These results indicate that multicollinearity is not a concern.

Table 3 presents the regression results of the relationship between CEO narcissism and the firm’s cross-border growth. The results of models 1 and 2 indicate a positive and significant relationship between CEO narcissism and cross-border growth (β = 0.139, p < 0.01). Similarly, the results of models 3 and 4 show a positive and significant relationship between CEO narcissism and the cross-functional growth of firms, thus supporting H1a and H1b.

Moderation effect test

Table 4 presents the results of the moderation effect of corporate ownership on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firm cross-border growth. Model 3 showed that the regression coefficients of CEO narcissism and corporate ownership on cross-border growth are significant (β = 0.128 and β = − 0.135, p < 0.01). However, the regression coefficient of the interaction term on cross-border growth was not significant in model 4 (β = − 0.020, p > 0.1). Therefore, H2a was not supported.

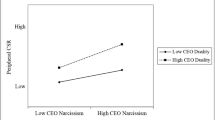

Table 5 displays the results of the moderation effect of corporate ownership on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firm cross-functional growth. Model 4 results indicate that the interaction term had a significant positive impact on firm cross-functional growth (β = 0.078, p < 0.05). The regression coefficient of CEO narcissism on firm cross-functional growth became larger compared to model 3 (β = 0.054, p < 0.05). These results suggest that CEO narcissism has a greater impact on the cross-functional growth of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) than that of non-SOEs. Thus, hypothesis 2b is supported.

We conducted further tests to examine the moderating effect of ownership concentration on the relationship between CEO narcissism and a firms’ cross-border growth. The results of model 4 in Table 6 show that the interaction term had a significant negative effect on firms’ cross-border growth (β = − 0.085, p < 0.01). Additionally, the effect of CEO narcissism becomes smaller (β = 0.131, p < 0.01), compared to the model 2 result without interaction (β = 0.139, p < 0.01). This suggests that the impact of CEO narcissism on cross-border growth is smaller for firms with high ownership concentration than for firms with low ownership concentration. Thus, H3a is supported.

Table 7 displays the results of the moderation regression of ownership concentration on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-functional growth. Results in model 4 reveal that the interaction term has a significant effect on firms’ cross-functional growth (β = − 0.063, p < 0.1). This suggests that the impact of CEO narcissism on cross-functional growth is less pronounced for firms with high ownership concentration than for those with low ownership concentration. Therefore, H3b is supported.

Robustness check

We conducted additional analyses to test the robustness of our results. Following the method of previous research (Ahuja & Katila, 2001; Song, 2002), we further examined the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth with a lag of two years. Regression results indicate that CEO narcissism has a positive relationship with a firms’ cross functional growth (0.114, p < 0.1). Furthermore, corporate ownership has a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-functional growth (0.270, p < 0.05). Due to space limitations, we cannot present the analysis results here, but they are available upon request. In summary, the results of the robustness tests are generally consistent with the main results.

Discussion and conclusion

Recognizing the conflicting impacts of CEO narcissism on firms’ strategy, it is essential to understand its role in the cross-boundary growth of firms. Motivated by this, our study integrates upper echelons theory and agency theory to examine how CEO narcissism influences a firm’s growth strategies and identifies potential moderating factors in this relationship. Using data from publicly listed manufacturing firms in China from 2005 to 2014, we find that CEO narcissism has a positive relationship with both cross-border growth and cross-functional growth. Additionally, we consider the contextual influence of corporate governance on the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ growth strategies. We find that, compared to non-SOEs, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and cross-functional growth is stronger for firms with SOE ownership. Moreover, compared to firms with high ownership concentration, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and cross-border growth is weaker for firms with high ownership concentration. Similarly, the positive relationship between CEO narcissism and cross-functional growth is also weaker for firms with high ownership concentration.

Theoretical contributions

Our study makes several contributions. Firstly, by investigating how CEO narcissism affects firms’ cross-boundary growth, we answer the call for a more nuanced understanding of the drivers of firms’ growth through micro factors (Chittoor et al., 2019; Kunisch et al., 2019). Our theoretical explanation is grounded in upper echelon theory, agency theory, and the literature on firms’ growth strategies. While previous research has explored factors affecting firms’ growth, these studies mainly focused on organizational characteristics such as size, resources, and networks (Ahammad et al., 2016; Hitt et al., 2006; Yuan et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016) and macro environment such as institutional environment (Boateng et al., 2008; Du & Boateng, 2015; Haxhi & Aguilera, 2017). By integrating and moving beyond this literature, our study illustrates how CEO personality, such as narcissism, affects a firm’s growth strategy. More specifically, narcissistic CEOs have a greater inclination for risk-taking, which aligns with the high-risk nature of cross-border expansion. Their confidence and willingness to accept challenges make them more likely to explore new market environments and seize opportunities for international growth. In addition, narcissistic CEOs exhibit a tendency to adopt radical exploration approaches to attract stakeholder and public attention. Pursuing cross-border growth allows them to showcase their superior abilities and assert their competitive position, which aligns with their attention-seeking tendencies. These motivations indicate that narcissistic CEOs are well-positioned to drive firms’ cross-border growth, leveraging their risk tolerance and attention-seeking behavior to navigate the challenges and seize opportunities in foreign markets.

Our second contribution is the recognition of two types of cross-boundary growth and the exploration of how they are affected by CEO narcissism. Our study contributes to the international business literature by examining how personal factors such as CEO narcissism affects a firms’ international expansion strategy (Kaczmarek & Ruigrok, 2013; Li, 2018). Our research highlights that despite high risk and unpredictability involved in cross-border growth (Zaheer, 1995; Zhang, 2020; Zhou & Guillen, 2016), firms with narcissistic CEOs are more likely to take this growth approach. Although design and production are the major activities for manufacturing firms, we find that firms with narcissistic CEOs tend to promote cross-functional growth within the value chain in the domestic market. Thus, our study depicts a richer picture of how CEO narcissism affects firms’ growth strategy both internationally and domestically. CEO narcissism can act as a catalyst for firms to pursue international opportunities, leading to increased market share, revenue growth, and access to new resources, as firms with narcissistic CEOs who embrace cross-border growth may gain a competitive advantage by being more willing to explore new markets, seize opportunities, and take bold strategic actions (Cragun et al., 2020; Oesterle et al., 2016). Furthermore, narcissistic CEOs have the potential to drive innovation and encourage the exploration of new growth avenues within their domestic markets. This can enhance a firm’s adaptability, facilitate the introduction of new products or services, and contribute to long-term growth (Gerstner et al., 2013; Wales et al., 2013).

Third, in focusing on the moderating role of corporate ownership and ownership concentration, we provide a more nuanced and accurate model outlining how the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-boundary growth is contingent on the feature of corporate governance. Previous research emphasizes the coexistence of different ownership types and their differential influence in firms’ decision-making in emerging markets such as China and India (De Beule & Duanmu, 2012; Deng, 2012), our findings show that compared with non-SOEs, SOEs with narcissistic CEOs are more likely to pursue cross-functional growth, probably because SOEs have privilege of domestic resource and market access. We further find that high ownership concentration weakens the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ cross-border growth and cross-functional growth. Integrating with agency theory, we argue that in firms with high ownership concentration, shareholders have power and act as counter force to narcissistic CEOs’ growth strategies. An in-depth understanding of firm’s governance structure holds the key to unravel the relationship between CEO traits and firm strategy in emerging markets (Filatotchev et al., 2007; Young et al., 2008).

Practical implications

Our study has several managerial implications. Firstly, it is widely acknowledged that CEO plays a significant role in a firm’s strategy making and implementation. Thus, there may be potential benefits of hiring a narcissistic CEO, such as overcoming strategic inertia and timely responding to the changing environment. Industries and business characterized by rapid adaptation, risk-taking, startups, high-growth ventures, sales and marketing-driven companies, and turnaround situations can benefit from the bold leadership style of a narcissistic CEO, who possesses visionary abilities and persuasive skills. However, narcissistic CEOs may pose risks and uncertainties in collaborative industries, where their self-centered nature hinders teamwork and communication. They may neglect long-term strategic planning in favor of short-term personal gains, which can hinder sustainable growth. Additionally, in industries emphasizing ethics and reputation, their tendency to prioritize personal interests over ethical considerations can lead to questionable decision-making and reputational damage.

Secondly, some studies have identified the risk of unrelated diversification (Boschma & Capone, 2015; Khanna & Palepu, 2000). Therefore, we suggest that narcissistic CEOs pursue a relevant growth strategy (Boschma, 2017; Markides & Williamson, 1994), focusing on synergizing with existing operations and distribution channels, and expanding the business into related markets that are strategically similar to its core business. For example, by aligning growth strategies with their organization’s strengths, market trends, customer needs, collaborative opportunities, and innovation initiatives, narcissistic CEOs can identify and capitalize on growth opportunities that are relevant and aligned with their business objectives. One illustration of this is seen in the case of Alibaba, where its founder Jack Ma’s charismatic and bold leadership propelled the company’s growth and expansion into various e-commerce domains, including B2B, B2C, and digital payments (Liu & Avery, 2021).

Thirdly, a dilemma for stakeholders exists that warrants attention (Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, 2019). As per the agency theory, CEOs could potentially prioritize their self-interest over the shareholders’ interests. To rectify this, a robust accountability system needs to be incorporated within the corporate governance framework, tasked with assessing and overseeing the CEO’s decisions and actions. This system might encourage a narcissistic CEO to adjust their decisions to optimally benefit the shareholders. Factors contributing to the accountability system could include a vigilant board of directors, clear delineation of duties, stringent performance reviews, and transparent communication practices. For instance, Tencent Holdings, a leading Chinese tech company, has built a robust corporate governance framework. It consists of distinct committees filled with Non-Executive Directors to hold key decision-makers, including the CEO, accountable (Tencent, 2018). This system has effectively balanced management and oversight, contributing to Tencent’s sustainable growth by aligning CEO decisions with shareholder interests.

Limitations and future research direction

While our study makes valuable contributions, it is important to acknowledge its limitations, which in turn provide opportunities for future research exploration. Firstly, given that our database is confined to a singular country and industry, the broad applicability of our results to different regions and sectors may be limited. Scholars have pointed out the importance of contextual factors when studying firms’ strategies and outcomes (Gaur et al., 2018; Zhang & Guido, 2019). Hence, subsequent research should aim to validate our findings across various geographic and industry contexts. Secondly, while our research adopted measures from prior studies, the characterization of CEO narcissism could be enhanced to better suit the cultural backdrop of Asian countries. Cultural variables have been proven to significantly impact the manifestation and perception of personality traits (Foster et al., 2003). Therefore, additional work could refine the cultural sensitivity of such measures.

Thirdly, our dataset is founded on panel data of publicly listed firms spanning from 2005 to 2014. With the rapidly evolving business environment, data collected in recent years may present different patterns. Thus, future work should aim to corroborate our findings with more recent, systematic data sets. Finally, future research could delve deeper into the mechanisms via which CEO narcissism influences firms’ cross-boundary growth. This could be achieved by introducing additional firm-level variables or adopting qualitative research methods to develop a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms. These limitations notwithstanding, we believe our research significantly furthers the understanding of the influence of CEO narcissism on firms’ growth strategies, setting the stage for future explorations in this area.

Conclusion

In summary, integrating upper echelon theory and agency theory and extending the literature on firms’ growth strategy, our study finds that CEO narcissism has a positive effect on firms’ cross-boundary growth, both domestically and internationally. Our study further sheds light on the differentiating role of corporate ownership and ownership concertation in affecting this relationship. We believe our study has provided a richer understanding of the relationship between CEO narcissism and firms’ growth strategy and hope that it will stimulate further research on this topic.

References

Adelman, M. A. (1955). Concept and statistical measurement of vertical integration. In G. J. Stigler (Ed.), Business concentration and price policy (pp. 281–322). National Bureau of Economic Research Inc.

Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2019). CEO Narcissism and Internationalization by Indian Firms. Management International Review, 59(6), 889–918.

Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2021). CEO narcissism and myopic management. Industrial Marketing Management, 97(8), 145–158.

Ahammad, M. F., Tarba, S. Y., & Liu, Y. (2016). Knowledge transfer and cross-border acquisition performance: The impact of cultural distance and employee retention. International Business Review, 25(1), 66–75.

Ahmad, S., & Omar, R. (2016). Basic corporate governance models: A systematic review. International Journal of Law and Management, 58(1), 73–107.

Ahuja, G., & Katila, R. (2001). Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of acquiring firms: A longitudinal study. Strategic Management Journal, 22(3), 197–220.

Baysinger, B. D., Kosnik, R. D., & Turk, T. A. (1991). Effects of board and ownership structure on corporate R&D strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 205–214.

Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A. S. L. I., Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2008). Finance, firm size, and growth. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(7), 1379–1405.

Birkinshaw, J., Ambos, T. C., & Bouquet, C. (2017). Boundary spanning activities of corporate HQ executives insights from a longitudinal study. Journal of Management Studies, 54(5), 422–454.

Blair, M. M. (1996). Ownership and control: Rethinking corporate governance for the twenty-first Century. Brookings Institution.

Boateng, A., Qian, W., & Tianle, Y. (2008). Cross-border M&As by Chinese firms: An analysis of strategic motives and performance. Thunderbird International Business Review, 50(4), 259–270.

Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364.

Boschma, R., & Capone, G. (2015). Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Research Policy, 44(10), 1902–1914.

Campbell, W. K. (1999). Narcissism and romantic attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1254–1270.

Campbell, W. K., & Foster, J. D. (2007). The narcissistic self: Background, and extended agency model, and ongoing controversies. In C. Sedikides & S. Spencer (Eds.), The self, frontiers of social psychology. Psychology Press.

Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. (2011). The handbook of narcissism and narcissistic personality disorder: theoretical approaches, empirical findings, and treatments (pp. 71–88). Wiley.

Chakraborty, A., Gao, L., & Sheikh, S. (2019). Corporate governance and risk in cross-listed and Canadian only companies. Management Decision, 57(10), 2740–2757.

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 351–386.

Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2011). Executive personality, capability cues, and risk taking: How narcissistic CEOs react to their successes and stumbles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56(2), 202–237.

Chatterjee, A., & Pollock, T. G. (2017). Master of puppets: How narcissistic CEOs construct their professional worlds. Academy of Management Review, 42(4), 703–725.

Chen, G., Firth, M., Gao, D. N., & Rui, O. M. (2006). Ownership structure, corporate governance, and fraud: Evidence from China. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 424–448.

Chittoor, R., Aulakh, P. S., & Ray, S. (2019). Microfoundations of firm internationalization: The owner CEO effect. Global Strategy Journal, 9(1), 42–65.

Claessens, S., & Yurtoglu, B. B. (2013). Corporate governance in emerging markets: A survey. Emerging Markets Review, 15(4), 1–33.

Cragun, O., Olsen, K., & Wright, P. M. (2020). Making CEO Narcissism research great: A review and meta-analysis of CEO narcissism. Journal of Management, 46(6), 908–936.

Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice-Hall.

Daily, C. M., Dalton, D. R., & Cannella, A. A., Jr. (2003). Corporate governance: Decades of dialogue and data. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 371–382.

De Beule, F., & Duanmu, J. L. (2012). Locational determinants of internationalization: A firm-level analysis of Chinese and Indian acquisitions. European Management Journal, 30(3), 264–277.

Deng, P. (2012). The internationalization of Chinese firms: A critical review and future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), 408–427.

Denis, D. J., Denis, D. K., & Sarin, A. (1999). Agency theory and the influence of equity ownership concentration on corporate diversification strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 20(11), 1071–1076.

Ding, Y., Zhang, H., & Zhang, J. (2007). Private vs state ownership and earnings management: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(2), 223–238.

Du, M., & Boateng, A. (2015). State ownership, institutional effects and value creation in cross-border mergers & acquisitions by Chinese firms. International Business Review, 24(3), 430–442.

Dubofsky, P., & Varadarajan, P. R. (1987). Diversification and measures of performance: Additional empirical evidence. Academy of Management Journal, 30(3), 597–608.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 11–17.

Farwell, L., & Wohlwend-Lloyd, R. (1998). Narcissistic processes: Optimistic expectations, favorable self-evaluations, and self-enhancing attributions. Journal of Personality, 66(1), 65–83.

Filatotchev, I., Strange, R., Piesse, J., & Lien, Y.-C. (2007). FDI by firms from newly industrialised economies in emerging markets: Corporate governance, entry mode and location. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 556–572.

Foster, J. D., Campbell, W. K., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 469–486.

Fuente, G., & Velasco, P. (2019). Capital structure and corporate diversification: Is debt a panacea for the diversification discount? Journal of Banking & Finance, 111(2), 105728.

Garnaut, R., Song, L., Tenev, S., & Yao, Y. (2005). China’s ownership transformation: Process, outcomes, prospects. World Bank.

Gaur, A. S., Ma, X., & Ding, Z. (2018). Home country supportiveness/unfavorableness and outward foreign direct investment from China. Journal of International Business Studies, 49, 324–345.

Gerstner, W. C., König, A., Enders, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2013). CEO narcissism, audience engagement, and organizational adoption of technological discontinuities. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(2), 257–291.

Goerzen, A. (2018). Small firm boundary-spanning via bridging ties: Achieving international connectivity via cross-border inter-cluster alliances. Journal of International Management, 24(2), 153–164.

Ham, C., Seybert, N., & Wang, S. (2018). Narcissism is a bad sign: CEO signature size, investment, and performance. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(1), 234–264.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Haxhi, I., & Aguilera, R. V. (2017). An institutional configurational approach to cross-national diversity in corporate governance. Journal of Management Studies, 54(3), 261–303.

Hitt, M. A., Tihanyi, L., Miller, T., & Connelly, B. (2006). International diversification: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management, 32(6), 831–867.

Hunt, R. A. (2021). Entrepreneurial orientation and the fate of corporate acquisitions. Journal of Business Research, 122(1), 241–255.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership concentration. Journal of Finance, 3(4), 305–360.

Johanson, J., & Vahlne, J. E. (2009). The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(9), 1411–1431.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 206–219.

Judge, T. A., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2006). Loving yourself abundantly: Relationship of the narcissistic personality to self and other perceptions of workplace deviance, leadership, and task and contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 762–776.

Kaczmarek, S., & Ruigrok, W. (2013). In at the deep end of firm internationalization: Nationality diversity on top management teams matters. Management International Review, 53, 513–534.

Kaplinsky, R., & Morris, M. (2000). A handbook for value chain research (Vol. 113). University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies.

Kaufmann, A., & Tödtling, F. (2001). Science–industry interaction in the process of innovation: The importance of boundary-crossing between systems. Research Policy, 30(5), 791–804.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. (2000). The future of business groups in emerging markets: Long-run evidence from Chile. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 268–285.

Kim, C., Kim, S., & Pantzalis, C. (2001). Firm diversification and earnings volatility: An empirical analysis of US–based MNCs. American Business Review, 19(1), 26–38.

Kohut, H. (2009). The restoration of the self. Chicago University Press.

Kunisch, S., Menz, M., & Cannella, A. A. (2019). The CEO as a key microfoundation of global strategy: T ask demands, CEO origin, and the CEO’s international background. Global Strategy Journal, 9(1), 19–41.

Leenders, M. A., & Wierenga, B. (2002). The effectiveness of different mechanisms for integrating marketing and R&D. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 19(4), 305–317.

Lemmon, M. L., & Lins, K. V. (2003). Ownership structure, corporate governance, and firm value: Evidence from the East Asian financial crisis. Journal of Finance, 58(4), 1445–1468.

Li, J., & Tang, Y. (2010). CEO hubris and firm risk taking in China: The moderating role of managerial discretion. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 45–68.

Li, P. Y. (2018). Top management team characteristics and firm internationalization: The moderating role of the size of middle managers. International Business Review, 27(1), 125–138.

Li, W., He, A., Lan, H., & Yiu, D. (2012). Political connections and corporate diversification in emerging economies: Evidence from China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(3), 799–818.

Li, Y., Guo, H., Yi, Y., & Liu, Y. (2010). Ownership concentration and product innovation in Chinese firms: The mediating role of learning orientation. Management and Organization Review, 6(1), 77–100.

Liang, H., Ren, B., & Sun, S. L. (2015). An anatomy of state control in the globalization of state-owned enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(2), 223–240.

Liu, H., & Li, K. (2002). Strategic implications of emerging Chinese multinationals: The Haier case study. European Management Journal, 20(6), 699–706.

Liu, S., & Avery, M. (2021). Aibaba the inside story behind Jack Ma and the creation of the world’s biggest online marketplace. HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

Liu, Y., Li, Y., & Xue, J. (2011). Ownership, strategic orientation and internationalization in emerging markets. Journal of World Business, 46(3), 381–393.

Lu, L. T. (2017). Strategic planning for **aomi: Smart phones, crisis, turning point. International Business Research, 10(8), 149.

Luo, Y., & Junkunc, M. (2008). How private enterprises respond to government bureaucracy in emerging economies: The effects of entrepreneurial type and governance. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 133–153.

Maccoby, M. (2000). Narcissistic leaders. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 69–77.

Macpherson, A., & Holt, R. (2007). Knowledge, learning and small firm growth: A systematic review of the evidence. Research Policy, 36(2), 172–192.

March, J. G., & Simon, H. A. (1958). Organizations. Wiley.

Markides, C. C., & Williamson, P. J. (1994). Related diversification, core competences and corporate performance. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S2), 149–165.

Moore, D. A., & Healy, P. J. (2008). The trouble with overconfidence. Psychological Review, 115(2), 502–517.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196.

Nadkarni, S., & Herrmann, P. O. L. (2010). CEO personality, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The case of the Indian business process outsourcing industry. Academy of Management Journal, 53(5), 1050–1073.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. A. (2020). Transformational leader or narcissist? How grandiose narcissists can create and destroy organizations and institutions. California Management Review, 62(3), 5–27.

O’Reilly, C. A., Doerr, B., Caldwell, D. F., & Chatman, J. A. (2014). Narcissistic CEOs and executive compensation. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(2), 218–231.

Oesterle, M. J., Elosge, C., & Elosge, L. (2016). Me, Myself and I: The role of narcissism in internationalization. International Business Review, 25(5), 1114–1123.

Palich, L. E., Cardinal, L. B., & Miller, C. C. (2000). Curvilinearity in the diversification–performance linkage: An examination of over three decades of research. Strategic Management Journal, 21(2), 155–174.

Patel, C., & Cooper, D. (2014). The harder they fall, the faster they rise: Approach and avoidance focus in narcissistic CEOs. Strategic Management Journal, 35(10), 1528–1540.

Patterson, P. G., Scott, J., & Uncles, M. D. (2010). How the local competition defeated a global brand: The case of Starbucks. Australasian Marketing Journal, 18(1), 41–47.

Peterson, R. S., Smith, D. B., Martorana, P. V., & Owens, P. D. (2003). The impact of chief executive officer personality on top management team dynamics: One mechanism by which leadership affects organizational performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 795–808.

Porta, R. L., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Corporate ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Technology and competitive advantage. Journal of Business Strategy, 5(3), 60–78.

Ramaswamy, K., Kroeck, K. G., & Renforth, W. (1996). Measuring the degree of internationalization of a firm: A comment. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(1), 167–177.

Raskin, R. N., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 54(5), 890–902.

Resick, C. J., Whitman, D. S., Weingarden, S. M., & Hiller, N. J. (2009). The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: Examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1365–1381.

Rosenkopf, L., & Nerkar, A. (2001). Beyond local search: Boundary-spanning, exploration, and impact in the optical disk industry. Strategic Management Journal, 22(4), 287–306.

Rosenthal, S. A., & Pittinsky, T. L. (2006). Narcissistic Leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 617–633.

Schommer, M., Richter, A., & Karna, A. (2019). Does the diversification-firm performance relationship change over time? A meta-analytical review. Journal of Management Studies, 56(1), 270–298.

Schotter, A. P., Mudambi, R., Doz, Y. L., & Gaur, A. (2017). Boundary spanning in global organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 54(4), 403–421.

Sharma, A., & Grant, D. (2011). Narrative, drama and charismatic leadership: The case of Apple’s Steve Jobs. Leadership, 7(1), 3–26.

Sheikh, S. (2019). CEO power and corporate risk: The impact of market competition and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 27(5), 358–377.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

Song, J. (2002). Firm capabilities and technology ladders: Sequential foreign direct investments of Japanese electronics firms in East Asia. Strategic Management Journal, 23(3), 191–210.

Song, X. M., Montoya-Weiss, M. M., & Schmidt, J. B. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of cross-functional cooperation: A comparison of R&D, manufacturing, and marketing perspectives. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14(1), 35–47.

Tenscent. (2018). Corporate Governance. Retrieved July 7, 2023, from https://www.tencent.com/en-us/investors/corporate-governance.html.

Tihanyi, L., Ellstrand, A. E., Daily, C. M., & Dalton, D. R. (2000). Composition of the top management team and firm international diversification. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1157–1177.

Troy, L. C., Hirunyawipada, T., & Paswan, A. K. (2008). Cross-functional integration and new product success: An empirical investigation of the findings. Journal of Marketing, 72(6), 132–146.

Ulrich, K. (1995). The role of product architecture in the manufacturing firm. Research Policy, 24(3), 419–440.

Vad Baunsgaard, V., & Clegg, S. (2013). ‘Walls or boxes’: The effects of professional identity, power and rationality on strategies for cross-functional integration. Organization Studies, 34(9), 1299–1325.

Wales, W. J., Patel, P. C., & Lumpkin, G. T. (2013). In pursuit of greatness: CEO narcissism, entrepreneurial orientation, and firm performance variance. Journal of Management Studies, 50(6), 1041–1069.

Wen, D. H., Tong, W. H., & Peng, X. (2015). CEO narcissism, ownership nature and organizational consequences–Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Business Management Journal, 37(8), 65–75.

**e, Z., Wang, J., & Miao, L. (2021). Big data and emerging market firms’ innovation in an open economy: The diversification strategy perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 173, 121091.

Yang, L. (2014). Research on the relationship between corporate ownership concentration, cognitive diversity of top management team and entrepreneurial strategy orientation. Science Research Management, 35(5), 93–106.

Yang, X., Jiang, Y., Kang, R., & Ke, Y. (2009). A comparative analysis of the internationalization of Chinese and Japanese firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(1), 141–162.

Yang, Z., Zhou, X., & Zhang, P. (2015). Discipline versus passion: Collectivism, centralization, and ambidextrous innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(3), 745–769.

Young, M. N., Peng, M. W., Ahlstrom, D., Bruton, G. D., & Jiang, Y. (2008). Corporate governance in emerging economies: A review of the principal–principal perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 45(1), 196–220.

Yuan, L., Wei, Z., & Yi, L. (2010). Strategic orientations, knowledge acquisition, and firm performance: The perspective of the vendor in cross-border outsourcing. Journal of Management Studies, 47(8), 1457–1482.

Zaheer, S. (1995). Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 341–363.

Zahra, S. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hitt, M. A. (2000). International expansion by new venture firms: International diversity, mode of market entry, technological learning, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 925–950.

Zhang, C. (2020). Formal and informal institutional legacies and inward foreign direct investment into firms: Evidence from China. Journal of International Business Studies, 53, 1–29.

Zhang, C. M., & Guido. (2019). Partnering with whom and how? An institutional perspective on entrepreneurial team composing and trust develo**. In T. K. Das (Ed.), Entrepreneurship and Behavioral Strategy. Information Age Publishing.

Zhang, C., Tan, J., & Tan, D. (2016). Fit by adaptation or fit by founding? A comparative study of existing and new entrepreneurial cohorts in China. Strategic Management Journal, 37(5), 911–931.

Zhang, H., Ou, A. Y., Tsui, A. S., & Wang, H. (2017a). CEO humility, narcissism and firm innovation: A paradox perspective on CEO traits. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(5), 585–604.

Zhang, J., Zhang, Q., & Liu, Z. (2017b). The political logic of partial reform of China’s state-owned enterprises. Asian Survey, 57(3), 395–415.

Zhang, Y., & Qu, H. (2016). The impact of CEO succession with gender change on firm performance and successor early departure: Evidence from China’s publicly listed companies in 1997–2010. Academy of Management Journal, 59(5), 1845–1868.

Zhou, N., & Guillen, M. F. (2016). Categorizing the liability of foreignness: Ownership, location, and internalization-specific dimensions. Global Strategy Journal, 6(4), 309–329.

Zhu, D. H., & Chen, G. (2015a). Narcissism, director selection, and risk-taking spending. Strategic Management Journal, 36(13), 2075–2098.

Zhu, D. H., & Chen, G. (2015b). CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(1), 31–65.

Zhu, Q., Hu, S., & Shen, W. (2020). Why do some insider CEOs make more strategic changes than others? The impact of prior board experience on new CEO insiderness. Strategic Management Journal, 41(10), 1933–1951.

Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model: Recent developments and future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1019–1042.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Key project of National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. AGL22019)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Yang, J., Zhang, C. et al. CEO narcissism and cross-boundary growth: Evidence from Chinese publicly listed manufacturing firms. Asian Bus Manage 22, 2164–2188 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00246-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-023-00246-1