Abstract

The influences of a home country’s economic and political institutions on acquirers’ cross-border acquisitions (CBAs) ownership strategies remains unexplored. Acquirers face endogenous uncertainty (i.e., uncertainty that can be resolved in part by acquirers) when transferring headquarters resources to foreign target firms and exogenous uncertainty (i.e., uncertainty that cannot be resolved by acquirers) when there is an unpredictable policy change. We argue that well-developed economic and political institutions in a home country play a market-supporting and constraining role in mitigating endogenous and exogenous uncertainty respectively, enabling acquirers to seek high ownership stakes in CBAs. We also argue that the importance of a home country’s well-developed economic and political institutions for acquirers’ CBA ownership strategic decisions depends on mutual trade dependence between the acquirers’ home country and the target firms’ host countries and also on the economic capabilities of the acquirers developed in different industries and political capabilities developed in different host countries. To test these arguments, we analyze 133,623 CBAs between 2000 and 2020 and find support for the distinct roles played by a home country’s economic and political institutions.

Plain language summary

In the intricate realm of global commerce, firms often aim to broaden their influence by purchasing businesses in foreign nations. This procedure, termed as cross-border acquisition (CBA – a strategic business decision to acquire a certain level of ownership in a foreign company), has been studied extensively in relation to the impact of the target country’s environment. However, the influence of a firm’s home country on its strategy has been less explored. This research seeks to address this by investigating how a firm's home country's economic and political structures impact its ownership choices in CBAs.

This study utilized a substantial dataset from the Financial Securities Data Company Platinum database, which comprised 133,623 records from 72 home countries and 59 host countries, spanning the years 2000 to 2020. The research examined how mature economic and political structures in the home country can aid firms in managing uncertainties linked to CBAs. It also took into account the role of mutual trade reliance between the home and host countries and the abilities of the acquiring firms across various industries and political climates.

The results indicate that firms from nations with robust economic structures are more inclined to seek a larger equity share in their CBAs. This is because these structures can offer a skilled labor force that eases the resource transfer and integration of the purchased company. Likewise, mature political structures can diminish uncertainty related to policy shifts in the home country, prompting firms to take a larger ownership stake. Furthermore, the study discovered that the correlation between home-country structures and ownership choices is affected by the trade level between the home and host countries and the acquiring firm’s capabilities.

The implications of this research are substantial for both business executives and policymakers. Firms should contemplate how their home country's structures can bolster their international expansion strategies. Policymakers can also utilize this knowledge to cultivate environments that encourage successful cross-border business activities, potentially leading to economic growth.

In conclusion, this study enhances our comprehension of the strategic choices firms make in cross-border acquisitions. It underscores the significance of home-country structures and offers insights into how firms can utilize these structures to thrive in the global marketplace. This text was initially drafted using artificial intelligence, then reviewed by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Résumé

Restent inexplorées les influences des institutions économiques et politiques du pays d'origine sur les stratégies de propriété des acquéreurs dans le cadre d'acquisitions transfrontalières (Cross-Border Acquisitions—CBAs). Les acquéreurs sont confrontés à une incertitude endogène (c'est-à-dire une incertitude qui peut être résolue en partie par les acquéreurs) lorsqu'ils transfèrent les ressources de leur siège à des entreprises cibles étrangères, et à une incertitude exogène (c'est-à-dire une incertitude qui ne peut être résolue par les acquéreurs) lorsqu'il y a un changement de politique imprévisible. Nous argumentons que des institutions économiques et politiques bien développées dans un pays d’origine jouent un rôle de soutien et de contrainte au marché en atténuant respectivement l’incertitude endogène et exogène, permettant aux acquéreurs de rechercher des participations élevées dans les CBAs. Nous argumentons également que l'importance des institutions économiques et politiques bien développées du pays d'origine pour les décisions stratégiques des acquéreurs en matière de propriété dans les CBAs dépend de la dépendance commerciale mutuelle entre le pays d'origine des acquéreurs et les pays d'accueil des entreprises cibles, ainsi que des capacités économiques des acquéreurs développées dans différents secteurs et des capacités politiques développées dans différents pays d'accueil. Pour tester ces arguments, nous analysons 133623 CBAs entre 2000 et 2020, et les résultats confirment les rôles distincts joués par les institutions économiques et politiques du pays d'origine.

Resumen

Las influencias de las instituciones económicas y políticas del país de origen sobre las estrategias de apropiación de las adquisiciones transfronterizas (CBAs por sus iniciales en inglés) de los adquirientes permanece aún inexplorado. Los adquirentes enfrentan incertidumbre endógena (es decir, incertidumbre que puede ser resuelta en parte por los adquirentes) al transferir recursos de la casa matriz a las empresas objetivo-extranjeras e incertidumbre exógena (es decir, incertidumbre que no puede ser resuelta por los adquirentes) cuando hay un cambio impredecible en las políticas. Argumentamos que las instituciones económicas y políticas bien desarrolladas en un país de origen desempeñan un papel de apoyo y restricción del mercado para mitigar la incertidumbre endógena y exógena, respectivamente, permitiendo a los adquirentes buscar altas participaciones de propiedad en las adquisiciones transfronterizas. También argumentamos que la importancia de las instituciones económicas y políticas bien desarrolladas del país de origen para las decisiones estratégicas de propiedad de la adquisición transfronteriza de los adquirentes depende de la dependencia comercial mutua entre el país de origen de los adquirentes y los países anfitriones de las empresas objetivo, así como de las capacidades económicas de los adquirentes desarrolladas en diferentes industrias y las capacidades políticas desarrolladas en diferentes países anfitriones. Para probar estos argumentos, analizamos 133.623 adquisiciones transfronterizas entre 2000 y 2020 y encontramos apoyo para los distintos roles desempeñados por las instituciones económicas y políticas del país de origen.

Resumo

As influências de instituições econômicas e políticas do país de origem nas estratégias de propriedade de adquirentes em aquisições transfronteiriças (CBAs) permanecem inexploradas. Adquirentes enfrentam incerteza endógena (ou seja, incerteza que pode ser resolvida em parte por adquirentes) ao transferir recursos da sede para empresas-alvo estrangeiras e incerteza exógena (ou seja, incerteza que não pode ser resolvida por adquirentes) quando há uma mudança de política imprevisível. Argumentamos que instituições econômicas e políticas bem desenvolvidas em um país de origem desempenham um papel de suporte e de restrição ao mercado na mitigação da incerteza endógena e exógena, respectivamente, permitindo que os adquirentes busquem altos níveis de participação nas CBAs. Também argumentamos que a importância das instituições econômicas e políticas bem desenvolvidas do país de origem para as decisões estratégicas de propriedade de CBA de adquirentes depende da dependência comercial mútua entre o país de origem dos adquirentes e os países anfitriões das empresas-alvo, bem como das capacidades econômicas dos adquirentes desenvolvidas em diferentes indústrias e das capacidades políticas desenvolvidas em diferentes países anfitriões. Para testar esses argumentos, analisamos 133.623 CBAs entre 2000 e 2020 e encontramos suporte para os distintos papéis desempenhados pelas instituições econômicas e políticas do país de origem.

摘要

母国的经济和政治制度对收购方跨境收购 (CBA) 所有权战略的影响仍未有探索。收购方在将总部资源转移到国外目标公司时面临内生不确定性(即收购方可以部分解决的不确定性), 而在发生不可预测的政策变化时面临外生不确定性(即收购方无法解决的不确定性)。我们认为, 母国发达的经济和政治制度分别在缓解内生和外生不确定性方面发挥着市场支持和制约作用, 能使收购方寻求在CBA中的高所有权股份。我们还认为, 母国发达的经济和政治制度对收购方的CBA所有权战略决策的重要性取决于收购方母国与目标公司东道国之间的相互贸易依赖性, 也取决于收购方在不同行业发展的经济能力和不同东道国发展的政治能力。为了验证这些论点, 我们分析了 2000 至 2020 年间的 133623 起CBA, 并发现其支持本国经济和政治机构所发挥的不同作用。

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The level of ownership acquired in a firm’s cross-border acquisitions (CBAs) is an important but underexplored strategic decision (Contractor et al., 2014) as a CBA of a foreign target firm involves the transfer of assets (Malhotra et al., 2016) and the acquisition of an already existing firm, which is different from an international joint venture. Although multinational enterprises (MNEs; i.e., acquirers) are deeply embedded in their home country and institutions play an important role in influencing firms’ ability to deploy strategic resources to succeed in foreign markets (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2011; Marano et al., 2016; North, 1990), studies have paid less attention to how home country’s formal institutions influence acquirers’ CBA ownership strategies (** or developed home country (see Online Appendix Table 1). Research has to explore which institutions in a home country provide institutional support or constraints relevant to acquirers’ CBA ownership strategies, and under what conditions home country’s economic and political institutions play a stronger or weaker role in those strategic decisions.

There are two main purposes of this study. First, we draw on institutional economics strand of institutional theory (North, 1990) to examine the distinct influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on acquirers’ CBAs ownership strategies, and argue that acquirers can benefit from the quality (indicated by the levels of development) of their home country’s economic and political institutions to deal with CBA-related uncertainties (i.e., endogenous uncertainty and exogenous uncertainty). Endogenous uncertainty is an uncertainty that can be resolved in part by the actions of acquirers (Chari & Chang, 2009), arising from a lack of skilled labor to facilitate the effective transfer of headquarters resources and the integration of foreign target firms (e.g., Malhotra et al., 2016); and exogenous uncertainty is an uncertainty that can’t be resolved by acquirers (Chari & Chang, 2009), arising from an unpredictable policy change and an uneven application of policies across firms (Falaster et al., 2021). We propose that well-developed economic and political institutions in their home country reduce the endogenous and exogenous uncertainty faced by acquirers respectively, and thus have positive influences on the share of equity sought in CBAs.

Second, we draw on insights of the political economy perspective of FDI (Pandya, 2016; Sally, 1994) to identify the boundary conditions of the influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on CBA ownership strategies. MNEs are embedded in an array of national and supranational institutional environments and the process of internationalization within global political economic structures (Sally, 1994). As MNEs are key actors in global production structures (Sally, 1994), the organization of their global production reflects the complementarities between trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) in the form of global production networks and their internalization within MNEs (Pandya, 2016). Trade between home and host countries is the cross-border flow of goods and services, and FDI is the cross-border flow of capacity to produce services and goods (Pandya, 2016). We argue that the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs depends on the mutual trade dependence between the acquiring and target countries; and propose that mutual trade dependence can strengthen the positive effect of home country’s economic institutions and weaken the positive effect of political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers. Moreover, foreign affiliates of MNEs (acquirers) are internally embedded in the MNE network (Meyer et al., 2020) and develop economic (market) and political (non-market) capabilities by operating in different industries and countries. Our study proposes that these economic and political capabilities can be leveraged to increase the positive influence of home country’s economic and political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers. To test our hypotheses, we use a sample of CBAs that were completed between 2000 and 2020. Our sample comes from the Financial Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum database, includes 133,623 observations, and consists of 72 home countries and 59 host countries.

Our study contributes to the literature on CBA ownership and institutional economics theory in two ways. First, this study examines the impact of home country’s institutions on CBA ownership strategies. Extant CBA studies have mainly focused on the institutional environment of the host country and suggested that host-country risks deter acquirers from seeking high ownership stakes although full acquisition allows acquirers to enjoy all future profits of foreign target firms (e.g., Chari & Chang, 2009; Piaskowska & Trojanowski, 2014). Other studies examining the institutional distance between host and home countries have revealed contrasting results as the CBA ownership strategies of acquirers from emerging economics differ from those of acquirers from developed economies (e.g., Malhotra et al., 2016; Pinto et al., 2017). Limited attention has been given to the role of home country’s institutions on foreign ownership strategies (Tang & Buckley, 2020) as existing CBA studies have primarily focused on the post-acquisition behavior and performance of acquirers in relation to institutions in a home country. This study reveals how acquirers can benefit from their home country’s economic and political institutions and seek high ownership stakes in foreign target firms.

Second, our study contributes to institutional economics theory by exploring the distinct roles played by home country’s economic and political institutions in mitigating endogenous uncertainty and exogenous uncertainty, respectively. Formal institutions are humanly devised constraints to create order and reduce the uncertainty of transacting in a market (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019; North, 1990). Little is known about which institutions in the home country can reduce these two types of uncertainty. This study illustrates the market-supporting role of home country’s economic institutions in mitigating endogenous uncertainty and the constraining role of home country’s political institutions in mitigating exogenous uncertainty. Our study also contributes to identify the boundary conditions of the influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs, as such influences can vary across acquirers due to the multiple embeddedness of MNEs (Meyer et al., 2020).

Theory and hypotheses

Research focusing on host-country environments has generally shown that acquirers opt for partial acquisition when host-country risks are high (Chari & Chang, 2009; Piaskowska & Trojanowski, 2014). Host-country risk is a source of exogenous uncertainty (e.g., lack of market infrastructure and institutional inefficiencies) that increases investment risks (Falaster et al., 2021; Moschieri et al., 2014). Although full acquisition allows acquirers to have full control over foreign target firms’ resources and capabilities, partial acquisition is an exit strategy if host-country risks cannot be resolved (Chari & Chang, 2009).

Another stream of studies focusing on home–host-country distance shows that acquirers from developed economies tend to take a partial equity stake in host countries with high cultural, geographical, institutional, linguistic, and religious distances (e.g., Contractor et al., 2014; Cuypers et al., 2015; Ragozzino, 2009). High home–host-country distance increases the risks of investment because acquirers do not know whether they can efficiently transfer their internal resources to the host country (Chen & Hennart, 2004; Malhotra et al., 2016); and intensifies information asymmetry problems, as it makes it difficult for acquirers to understand and transfer information from distant target markets and thus increases their information and organizational costs (Malhotra et al., 2016; Pinto et al., 2017).

In the same line of research, some studies have found that acquirers from emerging economies tend to pursue full acquisition or increase their equity stake in host countries with high home–host-country distance (Chikhouni et al., 2017; Elango & Pattnaik, 2011; Lahiri et al., 2014; Liou et al., 2016; Malhotra et al., 2016; Pinto et al., 2017). The rationale is that acquirers from emerging economies lack traditional competitive advantages and thus use high-control, high-risk CBA ownership strategies as a springboard to acquire critical resources and escape from institutional and market constraints in their home country. However, other studies have found that acquirers from emerging economies are less likely to opt for full acquisition in host countries with high cultural distance (e.g., Liou et al., 2016) and high psychic distance (Chikhouni et al., 2017).

While these studies have shown that the CBA ownership strategies of acquirers from emerging economies differ from those of acquirers from developed countries, they have paid less attention to the context of the home country where MNEs (acquirers) are deeply embedded because of their historical ties with local actors (e.g., government and industry associations) and their dependence on local infrastructure and local knowledge of national economies, as well as where they have their headquarters and carry out their main value-added activities (Sally, 1994). Although IB scholars have highlighted the importance of home-country contexts and institutions for firms’ global strategies (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra, 2016; Marano et al., 2016), previous studies have ignored the variation in institutions that can constrain or facilitate how acquirers from different home countries manage and integrate their foreign target firms (Zhu et al., 2019). Home-country contexts are important in global competition, as they provide competitive advantages to individual nations (Porter, 1990), shape the business ecosystems (Hobdariet al., 2017), and influence MNEs’ internationalization decisions (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2011). As home-country contexts are multifaceted institutional environments (North, 1990), institutions, which constitute economic and political institutions, play an important role in determining the economic performance of nations through support and uncertainty reduction mechanisms (Marano et al., 2016; North, 1990) and through transaction and transformation costs, thereby affecting the profitability of firms in a given country (North, 1990). Institutions also play an important role in affecting firms’ ability to acquire and deploy strategic resources and their key capabilities to succeed in foreign markets (Marano et al., 2016). However, research on foreign ownership strategies that take into account the formal institutions of the home country (Tang & Buckley, 2020) remains insufficient, with only two studies examining the moderating effects of weak home-country regulatory institutions and lack of skilled labor on the relationship between formal institutional distance and the share of equity sought by acquirers (Liou et al., 2016, 2017).

The choice of the level of ownership acquired in CBAs has important strategic impacts on the acquirers in terms of transfer of headquarters resources and control of the assets of foreign target firms (Chari & Chang, 2009; Malhotra et al., 2016). Acquirers typically face two types of uncertainty (i.e., endogenous and exogenous) when determining the share of equity sought in CBAs (e.g., Chari & Chang, 2009). First, acquirers face endogenous uncertainty arising from information asymmetry between acquirers and foreign target firms and between MNEs and the local environment, as foreign target firms possess more relevant information about the value of their assets and a better understanding of their operating environment than acquirers (Chari & Chang, 2009; Falaster et al., 2021); and also endogenous uncertainty arising from a lack of skilled labor to effectively transfer headquarters resources to the foreign target firm, as due diligence also focuses extensively on integration once an acquirer has announced its decision to acquire a target firm (Very & Schweiger, 2001). Second, acquirers face exogenous uncertainty not only in the host country (Chari & Chang, 2009) but also in their home country, as the government or policymakers in their own home country may adopt arbitrary measures that lead to an uneven application of policies among different firms, making it difficult for firms to predict how these policies will be applied (Falaster et al., 2021).

We propose that well-developed economic and political institutions in their home country reduce the endogenous and exogenous uncertainty faced by acquirers respectively, and thus increase the share of equity sought in CBAs. Specifically, well-developed economic institutions present constraints that structure the rules of exchange in the labor market (Chacar et al., 2010) and the efficiency of human capital exchange and investment (North, 1990), in turn increasing the size of the pool of skilled talent in the local labor market (Gautam, 2021). The availability of skilled labor in the labor market, representing essential human capital in the context of CBAs (e.g., Sarala et al., 2019; Tarbaet al., 2020), can allow acquirers to reduce endogenous uncertainty by facilitating access to skilled workers who can be employed to achieve an effective transfer of headquarters resources to foreign target firms. Well-developed political institutions create constraints and checks and balances for the government or policymakers (North, 1990), generating stable structures and limiting arbitrary and predatory actions, thereby reducing exogenous uncertainty in the home country. In the following section, we discuss how home country’s economic institutions (i.e., the effect of the availability of skilled labor) and political institutions (i.e., the effect of political constraints) influence the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

Home country’s economic institutions

Economic institutions in the home country contribute to labor market efficiency and investment in education to improve human capital for economic growth (North, 1990). They also lay the foundation for efficient exchange in the labor market and provide incentives for investment in human capital (Cantwell et al., 2010), reflecting the size of the pool of skilled labor (Chacar et al., 2010; Gautam, 2021).

When economic institutions are well developed, they make human capital more available through an efficient labor market and a well-developed education system (North, 1990). Well-developed economic institutions play a market-supporting role by ensuring a continuous supply of well-trained local talent (e.g., managers and professionals) for the labor market (Rabbiosi et al., 2012). Skilled workers embody the organizational skills and knowledge that enable the flow of information across firms through the mobility of skilled workers in the local market (Chacar et al., 2010), representing essential human resources for acquirers to determine the share of equity sought in CBAs (Park & Choi, 2014). The rationale is that acquirers face endogenous uncertainty regarding the transfer of headquarters resources to foreign target firms, as due diligence also focuses on effective integration once acquirers have decided to acquire a target firm (Tang & Zhao, 2024; Very & Schweiger, 2001). The effective integration of the foreign target firm implies a substantial commitment of the acquirer’s managerial resources (Cording et al., 2008) to transfer knowledge and combine the resources of the acquirer and the foreign target firm (Park & Choi, 2014). To ensure that their resources and knowledge are effectively transferred to foreign target firms and made available to CBAs, acquirers tend to fill top management positions in CBAs with their own staff and expatriate managers (Hébert et al., 2005; Park & Choi, 2014) and therefore need a large number of managerial talents to participate in all pre-acquisition stages (Tarba et al., 2020) and to be expatriate experts serving as important agents of change in the integration process (Sarala et al., 2019; Teerikangas et al., 2011). Given the availability of managerial talent in the local labor market, acquirers from a home country with well-developed economic institutions can minimize endogenous uncertainty, as they benefit from the continuous supply of well-trained local talentFootnote 1 who can be employed to help acquirers effectively transfer headquarters resources and integrate foreign target firms to generate value; as such, they are likely to seek a high share of equity in CBAs.

In contrast, when the economic institutions of the home country are less developed, there is a lack of well-developed institutional infrastructure (e.g., education systems) that facilitates the development of human resources to compete globally (Hitt et al., 2012; Liou et al., 2016; Pinto et al., 2017). Acquirers from home countries with less developed economic institutions face endogenous uncertainty, as they find it difficult to employ internationally savvy managerial talent from the local labor market (Hitt et al., 2012) and thus have limited confidence to effectively transfer headquarters resources and integrate foreign target firms to generate value because of a lack of management experience (Hitt et al., 2012). In this case, acquirers face high endogenous uncertainty and are less likely to seek a high share of equity in CBAs. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1a

There is a positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s economic institutions and the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

Home country’s political institutions

Political institutions in the home country create constraints or effective checks and balances for the government or policymakers (North, 1990). The government or policymakers set a country’s macroeconomic and microeconomic policies that affect MNEs (Bhaumik et al., 2024; Murtha & Lenway, 1994). They can commit to stable policies or change the regulatory system at their discretion (Bergara et al., 1998).

When political institutions are less developed, there are few adequately enforced constraints or checks and balances on the behavior of the government or policymakers (Henisz, 2000; Pandya, 2016), potentially leading to the implementation of predatory (Boubakri et al., 2013) and/or arbitrary actions (Falaster et al., 2021). The government or policymakers can change policies through regulatory or administrative procedures to adopt predatory actions (Bergara et al., 1998; Boubakri et al., 2013; Henisz, 2000). The change in policies increases exogenous uncertainty, as firms find it difficult to protect their interests against predatory actions, which reduce their likelihood of making substantial asset investments (Boubakri et al., 2013). The government or policymakers can also adopt arbitrary actions, as they can arbitrarily change the application of the rules of the game or policies, which may hinder some acquirers while favoring others that are in line with their political agenda (Falaster et al., 2021; Pinto et al., 2017). This uneven application of policies across acquirers increases exogenous uncertainty, as acquirers find it difficult to predict how these policies will be applied (Falaster et al., 2021). Although acquirers, being local firms, already know their home-country institutional environments, this unpredictability prevents them from using their accumulated knowledge and experience to make sense of the arbitrary application of policies (Murtha & Lenway, 1994). For example, the government or policymakers can arbitrarily change policies by conferring some selective firms and strategic industries privileges, such as fiscal incentives, subsidies, and loans (e.g., Chan & Du, 2021; Falaster et al., 2021). Without the constraints of political institutions in the home country, the government or policymakers can make frequent changes in the rules of the game (Bergara et al., 1998), resulting in increased exogenous uncertainty (Guler & Guillén, 2010). Firms in a home country with less developed political institutions are likely to be distracted by unpredictable home-country policies and are therefore unable to pay attention to and allocate resources to manage host-country risks (Tang & Buckley, 2020). Thus, acquirers are likely to have the foreign target firms retain a high share of ownership which encourages them to contribute more to deal with the host-country risks (Falaster et al., 2021) and seek a low share of equity in foreign target firms.

In contrast, when political institutions are well developed, there are constraints and multiple checks and balances in the policy-making process (Holburn & Zelner, 2010; Pandya, 2016). Well-developed political institutions can constrain the arbitrary and predatory actions of the government or policymakers (Guler & Guillén, 2010) because the government and policymakers are required to allocate national resources transparently and to support firms (e.g., strong legal protection) without privileging those that are in line with their political agenda (Marano et al., 2016; Tang & Buckley, 2020). Because of the predictable and stable implementation of policies and government support, acquirers are not distracted by unpredictable home-country policies and can focus on develo** their ability to deal with difficulties in host countries (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2011; Tang & Buckley, 2020), leading them to invest more in foreign countries (Chen et al., 2019)Footnote 2. As well-developed political institutions in home countries can mitigate exogenous uncertainty, acquirers are likely to seek a high share of equity in foreign target firms. Based on the discussion above, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1b

There is a positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s political institutions and the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

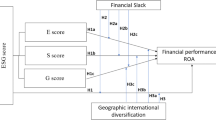

Although acquirers benefit from well-developed economic and political institutions in their home country to mitigate endogenous uncertainty and exogenous uncertainty, firms are heterogenous in their perceptions of institutional support and constraints (Guler & Guillén, 2010). We argue that the importance of well-developed economic and political institutions for acquirers’ CBA ownership strategic decisions depends on the multiple embeddedness of MNEs, as an MNE or acquirer is externally embedded in its home- and host-country contexts and its foreign affiliates are internally embedded in the MNE network. MNEs are important actors in global production structures (Sally, 1994) and decide strategically on their use of trade and/or FDI because their organization of global production reflects the complementarities between trade and FDI in the form of global production networks (Pandya, 2016). In general, acquirers face information asymmetry regarding the operating environment in the host country (Chari & Chang, 2009; Falaster et al., 2021) when evaluating their FDI decisions. Being externally embedded in both home- and host-country contexts (Meyer et al., 2020) and in the global political economy (Sally, 1994), MNEs are able to obtain more external information from trade flows between home and host countries (i.e., mutual trade dependence between the acquirers’ home country and the target firms’ host country); and may perceive a higher value of institutional support from home country’s institutions. In addition, mutual trade dependence reflects the strategic importance of mutually dependent resource environments (**a, 2011) required by the government or policymakers of the acquirers’ home country for economic growth; as such, the government or policymakers may not adopt arbitrary actions due to the benefits generated by mutual trade dependence. In this case, acquirers may perceive a lower value of institutional constraints provided by home country’s political institutions. Moreover, being internally embedded in the MNE network (Meyer et al., 2020), the economic (market) capabilities of foreign affiliates developed in different industries and their political (non-market) capabilities developed in different host countries can be leveraged within the MNE network to influence the relative importance of home country’s economic and political institutions in acquirers’ CBA ownership strategic decisions. In the following sections, we argue that the influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs depend on the mutual trade dependence between the acquiring and target countries and on the economic and political capabilities of the acquirers (see Fig. 1).

Mutual trade dependence

When the level of mutual trade dependence between a home country and a host country is high, there is a substantial cross-border exchange of resources between trading partners (i.e., importers and exporters), as trading partners in the home country depend on those in the host country for raw materials and the production of new or cheaper intermediate or final goods and services and vice versa (**a, 2011). These intensified cross-border exchanges facilitate direct information flows among trading partners and indirect information flows through market intermediaries and business networks (e.g., agents, brokers, supply chain partners, and banks) (Rauch, 2001). Mutual trade dependence provides an external information environment in which trading partners, market intermediaries, and information intermediaries (e.g., analysts and the business press) produce and disclose external information that helps not only MNEs evaluate their investment decisions (Shroff et al., 2014) but also acquirers collect more external information to expand their knowledge base. As the expanded knowledge base constitutes the reservoirs of headquarter resources (Kafouros et al., 2014), acquirers have a stronger need of the support of a people-based mechanism (e.g., expatriation) to successfully transfer their skills and knowledge to other foreign affiliates (acquired firms) (Hébert et al., 2005); and the market-supporting role played by well-developed economic institutions in mitigating endogenous uncertainty becomes more important. The rationale is that when the level of mutual trade dependence is high, well-developed economic institutions can ensure a continuous supply of local skilled workers who embody organizational skills and knowledge (North, 1990; Rabbiosi et al., 2012) and can be employed to incorporate their organizational skills and knowledge into acquirers’ expanded knowledge base, resulting from a continuous flow of information among trading parties in home and host countries, so that acquirers can be better able to achieve a more efficient transfer of headquarters resources to foreign target firms and more effective integration. Thus, we posit that a high level of mutual trade dependence strengthens the positive effect of home country’s economic institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

Hypothesis 2a

The positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s economic institutions and the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs is stronger when the level of mutual trade dependence is high rather than low.

Mutual trade dependence between a home country and a host country also reflects the strategic importance of resource-dependent environments (**a, 2011), as countries have comparative advantages arising from differences in factor endowments (e.g., capital, natural resources, and technology) between trading countries (Porter, 1990). When the level of mutual trade dependence between the acquirers’ home country and the target firms’ host country is high, the acquirers’ home country depends on the target firms’ host country for important resources (e.g., natural resources, technological resources, and intermediate goods), and vice versa. While trading natural resources enhances economic growth (Havranek et al., 2016), trading intermediate and final goods is also an important channel for knowledge spillovers between trading countries (Grossman & Helpman, 1991), which contributes to improved productivity through technology transfer; as a result, subsequent technological upgrading can further improve the competitiveness of local industries and the economic growth of emerging and developed countries (Wang et al., 2012). Given the benefits of mutual trade dependence, governments in both emerging and developed countries tend not to arbitrarily change policies at home, and thus the constraining role played by well-developed political institutions in the home country in mitigating the exogenous uncertainty that arises from arbitrary home-country policy changes is less important when the level of mutual dependence is high. We thus posit that a high level of mutual trade dependence weakens the positive effect of home country’s political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

Hypothesis 2b

The positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s political institutions and the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs is weaker when the level of mutual trade dependence is high rather than low.

Economic (market) and political (non-market) capabilities

In this section, we argue that the positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s economic institutions and the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs is stronger for acquirers with economic (market) capabilities. Economic capabilities are organizational skills and knowledge developed in a market or an industry to maintain competitive advantages (Teece, 1984). Acquirers develop economic capabilities by operating in different industries to accumulate industry-specific skills and knowledge about products and customer needs through interactions with customers, suppliers, intermediaries, and stakeholders (Lahiri et al., 2014). An acquirer with an MNE network in which foreign affiliates are internally embedded is better able to develop greater economic capabilities, as it can leverage the skills and knowledge accumulated by its foreign affiliates in many different industries to obtain new non-location-bounded knowledge bases (Hayward, 2002; Sartor & Beamish, 2020) to further create value. As the new non-location-bounded knowledge bases constitute the reservoirs of headquarter resources (Kafouros et al., 2014), acquirers with greater economic capabilities have a stronger need of the support of a people-based mechanism (e.g., expatriation) to successfully transfer their skills and knowledge to other foreign affiliates (acquired firms) (Hébert et al., 2005). In this case, well-developed economic institutions in a home country play a more important market-supporting role in mitigating endogenous uncertainty for acquirers with greater economic capabilities, because of a continuous supply of local skilled workers who can be employed to incorporate their organizational skills and knowledge into acquirers’ new non-location-bound knowledge base and can help acquirers effectively transfer headquarters resources and integrate foreign target firms to generate value. Thus, we posit that acquirers’ economic capabilities strengthen the positive effect of home country’s economic institutions on the share of equity sought in CBAs.

Hypothesis 3a

The economic capabilities of acquirers strengthen the positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s economic institutions and the share of equity they seek in CBAs.

We also argue that acquirers’ political capabilities can strengthen the positive influence of well-developed political institutions in a home country with respect to CBA ownership. Political capabilities are a firm’s ability to identify the preferences of key local political actors and address host-country risks (Holburn & Zelner, 2010; Oliver & Holzinger, 2008). Firms develop their political capabilities by operating in many host countries to accumulate different host country-specific experiences about the policy-making process and lobbying political actors (Hillman & Wan, 2005). An acquirer with an MNE network in which its foreign affiliates are internally embedded is better able to develop greater political capabilities, as it can leverage the experiences accumulated by its foreign affiliates in many host countries to manage institutional inefficiencies which differ from one host country to another (Falaster et al., 2021). Given that political capabilities constitute the competitive advantages of firms, acquirers with greater political capabilities have a stronger need of the constraints provided by well-developed political institutions which ensure that policymakers at home won’t arbitrarily change policies so that they won’t be distracted by unpredictable home-country policies (Tang & Buckley, 2020) and can better use their political capabilities to mitigate the negative effects of host-country risks and increase their long-term sustainability (Jiménez, 2010). In this case, well-developed political institutions in the home country play a more important constraining role in mitigating exogenous uncertainty faced by acquirers with greater political capabilities because of the enforced constraints on the arbitrary home-country policy changes and therefore have a stronger positive influence on the share of equity sought by acquirers with political capabilities in CBAs. Taken together, we posit that acquirers’ political capabilities strengthen the positive effect of home country’s political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs.

Hypothesis 3b

The political capabilities of acquirers strengthen the positive relationship between the level of development of home country’s political institutions and the share of equity they seek in CBAs.

Methodology

Sample

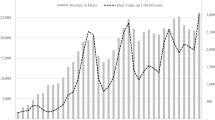

Our sample comes from the Financial Securities Data Company (SDC) Platinum database and includes all CBAs that were completed or withdrawn between 2000 and 2020. First, we remove all observations in which the acquirer has prior ownership in the foreign target firm, because the subsequent acquisition ownership decision may be endogenously determined and constrained by the first acquisition (Falaster et al., 2021). Second, we only include deals seeking more than 10% ownership, because investments below this threshold are typically considered portfolio investments. Third, we exclude rumored deals, asset divestitures, leveraged buyouts, exchange offers, and recapitalization. Our final sample includes 133,623 observations and consists of 72 home countries and 59 host countries (see Online Appendix Table 2).

Measures of variables

Share of equity sought

Our dependent variable is the share of equity sought by the acquirer in the CBA, with values ranging from 10 to 100%.

Home country’s economic institutions

Research has suggested that skilled labor is one of the most important supply-side institutional factors affecting a firm’s internationalization (Hitt et al., 2012). In our research setting, skilled labor refers to people heavily involved in the CBA process, such as managerial talent, professional experts (e.g., financial analysts, lawyers, and auditors), and technocrats for CBAs in the high-tech industry. We therefore measure home country’s economic institutions as the total number of individuals employed in (1) the financial and business services sector, (2) the professional group, and (3) the technician group, compared with the total labor force aged 15–64. This variable ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating well-developed economic institutions. The employment data are from the World Bank’s Global Jobs Indicators database. We standardize the scores on home country’s economic institutions to avoid multicollinearity in the interaction terms.

Home country’s political institutions

We adopt political constraint index, POLCON (Henisz, 2000), which captures the political structure of a country that constraints policymakers from unilaterally changing existing policy regimes. POLCON ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating the absence of effective veto players (i.e., complete concentration of policy-making authority). The government of a home country with a low POLCON score faces few political constraints to arbitrarily change existing policies (Holburn & Zelner, 2010). We standardize the scores on home country’s political institutions to avoid multicollinearity in the interaction terms.

Mutual trade dependence

We follow ** primary industries with which the focal acquirer has been involved during this 5-year period.

Acquirer’s political capabilities. We consider that acquirers accumulate political capabilities through the operation of their foreign affiliates in different policy environments. We first collect the POLCON scores of all host countries where the acquirer acquired one or more target firms in the 5-year period preceding the focal deal. Next, we calculate the acquirer’s political capabilities score as the variance of the POLCON scores of the host-country group in which the acquirer acquired foreign target firms.

On the acquirer side, we control for acquirer public listed status (a dummy variable that equals 1 for a listed acquirer and 0 otherwise), acquirer diversification (the number of industries in which the acquirer operates using four-digit SIC codes), and acquirer’s prior experience in the host country by counting the acquirer’s successful CBA experiences in the host country for the 5-year period preceding the focal deal.

On the target side, we control for target public listed status, which equals 1 if the target firm is publicly listed and 0 otherwise, target diversification (the number of industries in which the acquirer operates using four-digit SIC codes) and target industry relatedness to the acquiring firm (which equals 4 if the acquirer’s primary industry and the target’s primary industry overlap based on four-digit SIC codes, 3 if they overlap based on three-digit SIC codes, 2 if they overlap based on two-digit SIC codes, 1 if they overlap based on one-digit SIC codes, and 0 otherwise). We also account for industry-level restrictive FDI rules by including the target industry FDI restrictiveness index obtained from the FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index database of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). A score of 0 represents no regulatory restrictions, whereas 1 indicates that the host government fully restricts FDI in this industry.

We include a vector of distance variables between the acquirer’s home and host countries. Geographic distance is derived from the CEPII “Distance” database; it is measured by the natural logarithm of the great circle distance between two countries’ most important cities/agglomerations in terms of population. Cultural distance is calculated using the formula of Kogut and Singh (1988) based on data from Hofstede’s study (1984). Legal difference is a dummy variable obtained from the CEPII that equals 1 if the two countries have the same legal origin and 0 otherwise. Linguistic distance score is a five-point scale in which a higher score indicating greater language differences between two countries.

We also control for macroeconomic factors in both home and host countries that may generate exogenous uncertainty that cannot be resolved by a firm’s internal efforts. We include the natural logarithm of GDP and GDP per capita (in constant 2010 U.S. dollars) of the acquirer’s home and host countries in our estimations.

Model specifications

A firm’s ownership decision can only be observed if it enters the host country (Vasudeva et al., 2018). However, forward-looking acquirers are incentivized to make a high ownership commitment in host countries where they anticipate the good performance of mergers and acquisitions; and other unobserved factors may influence an acquirer’s market entry and CBA ownership decisions. As sample selection bias is a likely concern in CBA ownership decisions, we use Heckman’s (1979) two-stage method to address such selection-induced endogeneity. The first stage is a probit model that estimates the likelihood of an acquirer entering a particular host country from a set of potential host countries. Following the approach of Vasudeva et al. (2018), we construct the set of location choices for each CBA deal by including countries within the focal host country’s geographical region, based on the assumption that firms are likely to select countries from alternatives within their geographical region. We adopt the United Nations taxonomy of geographical regions by assigning potential host countries to one of five regions: Africa, Asia, the Americas, Europe, and Oceania.

The explanatory variables in the first-stage probit model include acquirer, home country, host country, and home–host dyad characteristics. Our analysis integrates two exclusion restrictions at this stage: the number of CBAs undertaken in the prospective host country by (1) acquirer’s peer firms originating from the same home country; and (2) by acquirer’s peers from the same industry. An investor’s FDI location decisions are likely to be influenced by the location activity of other firms originating from the same home country as well as those within the same industry. However, once entering the host market, these previous entries by peer firms do not exert a direct impact on the investor’s subsequent ownership decisions in the host market. In the second stage, our dependent variable, share of equity sought, is bounded at the 10% and 100% levels. The tobit model allows us to impose bounds on values other than 0 and, and also makes it possible to measure the effect of the dependent variables on the multiple features of the conditional distribution. We include year-fixed effects and host-country fixed effects in the first-stage and second-stage regressions. To handle potential serial correlations, we estimate all models using robust standard errors clustered by the acquirer–host country dyads. All explanatory variables and control variables are lagged by 1 year to avoid simultaneity.

Results

Table 1 presents the correlation matrices of the variables. The variance inflation factors for all of our variables range from 1.00 to 2.82, with a mean value of 1.57; these values are well below the accepted value of 10 for a multicollinearity test. This result indicates that multicollinearity is not an issue in our study. Table 2 presents the results of Heckman’s two-stage method. In Model 1, we report the results of the first-stage selection model that predicts the probability of entering a host country. In alignment with our predictions, both of our exclusion restrictions have a strong negative effect on the probability of market entry (p = 0.000). This finding underscores the significant role of competitive pressures emanating from its home-country/industry peers in diminishing the likelihood of an acquirer’s market entry into the host country. The low correlation between our two independent variables and the inverse Mills ratio (0.109 for home country’s economic institutions and 0.087 for home country’s political institutions), coupled with a high pseudo-R2 (0.292) in the first stage, robustly supports the validity of our exclusion restrictions. In Models 3 through 9, we report the results of the second-stage model that predicts the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs. Model 2 is the baseline model with all of the control variables. Models 3 and 4 show that the coefficients on home country’s economic institutions (β = 0.058, p = 0.000) and home country’s political institutions (β = 0.036, p = 0.000) are positive and significant, supporting Hypotheses 1a and 1b. We compute the marginal effect of home country’s economic institutions and political institutions, and compare it with that of another benchmark control variable (i.e., cultural distance). A one-standard-deviation increase in home country’s economic institutions (home country’s political institutions) from the sample mean increases the predicted share of equity sought by 1.1% (0.7%); meanwhile, a one-standard-deviation increase in cultural distance from the sample mean decreases the predicted share of equity sought by 0.8%. This comparison indicates that home country’s economic institutions and political institutions are at least as important as cultural distance in determining CBA ownership strategies. We also take the United States and Brazil as examples. We find that that an average acquirer in the United States, which has better economic and political institutions (0.190 and − 0.412, respectively) than Brazil, tends to seek a 2.9% higher ownership stake in a given CBA deal compared with an average acquirer in Brazil, which has less developed economic and political institutions (− 2.07 and − 0.94, respectively). Considering that the average share of equity sought in our sample is 88.9%, a 2.9% difference is non-trivial.

Model 5 shows that the interaction term between home country’s economic institutions and mutual trade dependence is positive and significant (β = 0.307, p = 0.000). Figure 2a presents the marginal effect of home country’s economic institutions on the predicted share of equity sought in both low dependence status (the solid line, with mutual trade dependence being 0) and high dependence status (the dashed line, with mutual trade dependence being 1 SD above the sample mean). A one-standard-deviation increase in home country’s economic institutions yields a two-fold increase in share of equity sought for high dependence status compared with low dependence status. Taken together, these findings provide strong support for Hypothesis 2a. Model 6 shows the negative interaction term between home country’s political institutions and mutual trade dependence (β = − 0.412, p = 0.000). Figure 2b presents the marginal effect of home country’s political institutions on the predicted share of equity sought in both low dependence status (the solid line, with mutual trade dependence being 0) and high dependence status (the dashed line, with mutual trade dependence being 1 SD above the sample mean), along with the 95% confidence intervals. Therefore, Hypothesis 2b is fully supported. Model 7 and Fig. 3a depict this relationship statistically and graphically, respectively. Consistent with this prediction, Model 7 shows that the interaction term between home country’s economic institutions and acquirer’s economic capabilities is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.001, p = 0.036). Figure 3a shows that the positive relationship between home country’s economic institutions and share of equity sought is stronger for acquirers with strong economic capabilities (the dashed line, with acquirer’s economic capabilities being 1 SD above the sample mean) than for acquirers with weak economic capabilities (the solid line, with acquirer’s economic capabilities being 0). However, the largely overlap** confidence intervals of the two lines provide only weak support for Hypothesis 3a. In Hypothesis 3b, we suggest that the positive effect in Hypothesis 1b is positively moderated by acquirer’s political capabilities. Model 8 shows that the interaction between home country’s political institutions and acquirer’s political capabilities is positive and significant (β = 0.582, p = 0.018), supporting Hypothesis 3b. However, this coefficient should be interpreted with caution, as Fig. 3b shows that the upward slo** trend is very similar between acquirers with weak political capabilities (the solid line, with acquirer’s political capabilities being 0) and acquirers with strong political capabilities (the dashed line, with acquirer’s political capabilities being 1 SD above the sample mean). We perform additional tests to confirm the robustness of our result (see Online Appendix Table 3).

a Interaction effects analysis: low vs. high mutual trade dependence. The influence of home country’s economic institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs. b Interaction effects analysis: low vs. high mutual trade dependence. The influence of home country’s political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs

a Interaction effects analysis: weak vs. strong economic capabilities. The influence of home country’s economic institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs. b Interaction effects analysis: weak vs. strong political capabilities. The influence of home country’s political institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs

Discussion

Our study examines whether home country’s institutions influence the share of equity sought by acquirers in CBAs. MNEs (acquirers) are deeply embedded in their home country where they have historical ties with local actors (Sally, 1994) who can provide institutional support and constraints to reduce uncertainty (North, 1990). However, research has paid limited attention to the influence of home country’s formal institutions on acquirers’ CBA ownership strategies (Tang & Buckley, 2020; ** their ability to deal with host-country risks (Tang & Buckley, 2020) and are likely to seek a high share of equity in foreign target firms.

Our study provides insight into the boundary conditions of the influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on acquirers’ CBA ownership strategies. Political economy scholars (e.g., Pandya, 2016) have argued that trade complements or replaces FDI depending on whether it involves vertical integration or manufacturing production. This study follows this line of thinking by investigating whether cross-border trade flows can strengthen or weaken the effect of home country’s institutions on the global strategies of MNEs. Our findings clearly show that acquirers’ CBA ownership strategic decisions are conditioned not only by the distance between home and host countries (e.g., Elango & Pattnaik, 2011) but also by the trade dependence of the two countries, as acquirers are externally embedded in the global political economy (Sally, 1994). Mutual trade dependence intensifies direct information flows among cross-border trading partners, allowing skilled labor at home to have more information to facilitate the transfer of headquarters resources and reducing endogenous uncertainty for acquirers; this, in turn, increases the positive influence of home country’s economic institutions on the share of equity sought by acquirers. However, mutual trade dependence weakens the positive influence of home country’s political institutions on ownership stakes, as mutual trade dependence improves the economic growth of countries, which triggers governments to adopt stable home–country policies and reduces the importance of the constraining role of their home country’s political institutions in mitigating exogenous uncertainty.

More importantly, the boundary conditions identified in this study also include acquirers’ economic (market) and political (non-market) capabilities developed by their foreign affiliates due to the multiple embeddedness of MNEs (Meyer et al., 2020). Institutional economics scholars generally assume that institutions govern business activities within their geographical jurisdiction (Alcacer & Ingram, 2013). However, a key question remains: How can acquirers benefit more from their home country’s institutions? According to the results of our study, we argue that acquirers can leverage the economic and political capabilities developed by their foreign affiliates in different industries and different host countries to reap the benefits of their home country’s economic and political institutions; as a result, acquirers are more likely to seek higher equity stakes in foreign target firms.

Managerial and policy implications

Our study has important implications for acquirers and policymakers. First, acquirers should pay more attention to the scope of their foreign subsidiaries to determine how they can further leverage the economic and political institutions of their home country. On the one hand, globalization in the 21st century enables MNEs to develop integrated global operations, and therefore capabilities to increase firms’ competitive advantages are indispensable; on the other hand, the changing international policy environment may create potential disruptions, and therefore the ability to react to policy-related risks is essential (Meyer et al., 2020). Given the importance of the scope of foreign subsidiaries, acquirers could diversify into different industries and develop diverse skills and knowledge to achieve economies of scope. This can be combined with their own reservoirs of shared knowledge resources with the help of new local talent, who can facilitate the effective integration of foreign target firms’ resources to enhance their firms’ competitive advantages. Similarly, acquirers could diversify into different host countries to respond differently to policy risks and broaden the political capabilities needed to deal with different levels of host-country political risk. As a result, they can benefit more from stable FDI policies implemented by the government or policymakers in their home country, as they are not distracted by unpredictable policies at home (Tang & Buckley, 2020) and can develop their core competence to increase their long-term sustainability (Jiménez, 2010). Therefore, corporate decision makers should reassess their industry portfolios and geographic footprints to ensure the efficacy of their subsidiaries’ strategy in terms of scope.

Second, acquirers should recognize the distinct roles played by the economic and political institutions of their home country, especially in emerging economies. MNEs from emerging economies tend to adopt a springboard approach to investing in more developed economies to acquire critical resources from foreign firms because of a lack of traditional competitive advantage (Lahiri et al., 2014; Malhotra et al., 2016), and to overcome weaknesses in home-country institutional quality because of a misalignment between firm-level needs and institutional constraints. However, MNEs tend to invest more efficiently due to the support of well-developed institutions in their home country (Chen et al., 2019). Although emerging economies are often characterized by weak institutional environments, the levels of development of economic and political institutions in some emerging economies are not necessarily low (see Online Appendix Table 1). Therefore, corporate decision makers should develop their CBA strategies according to the levels of development of their home country’s economic or political institutions.

Third, policymakers should recognize the importance of home country’s institutions and mutual trade dependence not only for firm-level CBA ownership strategic decisions but also for country-level economic growth. Political economy scholars have argued that MNEs are important actors in the global political and economic environment and that their global strategies play an important role in economic development (Pandya, 2016; Sally, 1994). To encourage FDI at the firm level, emerging economies can implement pro-market reforms to improve the business environment. As changes in one dimension of institutions are not necessarily accompanied by changes in other dimensions (Chan & Du, 2021), policymakers should ensure that the progress of pro-market reforms is synchronized to enable acquirers to reap the benefits of well-developed institutions at home. Policymakers should also promote cross-border trade flows at the country level. On the one hand, mutual trade dependence can facilitate home–host-country information flows, allowing skilled labor at home to collect more information to help acquirers mitigate endogenous uncertainty. On the other hand, mutual trade dependence can improve the competitiveness of local industries and the economic growth of countries by ensuring technology transfer and hence technological upgrading. Policymakers should make better use of their home country’s economic institutions and mutual trade flows to develop their country’s global competitive advantages.

Future research

Future research should explore the role of home country’s economic institutions in the ex post target management phase. Acquirers generally find it difficult to manage foreign target firms because their managers may lose incentives to cooperate, resist the implementation of acquirer decisions, or even leave the target firms; as such, well-trained expatriates are needed to monitor the post-acquisition activities of foreign target firms. As a large pool of internationally experienced human capital is available in home countries with well-developed economic institutions, it would be interesting to examine whether and how well-developed institutions in the home country influence CBA performance and the extent of that influence. Moreover, scholars of political economy and comparative capitalism (Ostrom, 2009) have argued that the effect of one institutional constituent may depend on the presence or absence of other institutional constituents at the same level (Holmes et al., 2013). To respond to a recent call for more research on the interrelationship between institutions and firms (Aguilera & Grøgaard, 2019), future research could explore how the interplay between economic and political institutions in the home country affect both CBA ownership strategic decisions and performance.

Another potential extension of our study would be to consider how higher-order institutions interact with home country’s institutions to positively or negatively influence CBA ownership decisions. Governments, as major actors in international politics, can pursue their interests through positive-sum cooperation (e.g., bilateral investment treaties and interstate security alliances). Bilateral investment treaties transcend the national borders of host and home countries to promote trade and investment, while interstate security alliances stabilize the international order. They represent higher-order institutional mechanisms that span the institutional abyss, serving as the ultimate authority over cross-border activities (Alcacer & Ingram, 2013). As governments may change their policy preferences and modify their foreign investment policies, future studies could investigate the extent to which and under what circumstances the formation of or exit from bilateral investment treaties and interstate security alliances facilitates or weakens the influences of home country’s economic and political institutions on CBA strategic ownership decisions.

In conclusion, drawing on institutional economics strand of institutional theory (North, 1990) and insights from the political economy perspective of FDI, our study contributes to the CBA ownership literature by confirming that home country’s institutions are an important but underexplored institutional context. Our study clearly reveals that home country’s economic and political institutions play important and distinct roles in influencing acquirers’ CBA ownership strategies, and their influences are conditioned by mutual trade dependence and acquirers’ economic and political capabilities.

Notes

Google completed a full acquisition of Photomath, a Croatian artificial intelligence firm. The U.S. Department of Labor has the public workforce system to connect businesses with skilled labor. The economic institutions score of United States is 0.19 while that of Croatia is – 0.63.

Tata acquired 100% ownership shares of Anglo-Dutch steel maker, Corus Group plc. The Indian government has adopted stable policies to improve domestic business environments. The political institution score of India is 1.48 which is much higher than that of Denmark (0.93).

References

Aguilera, R. V., & Grøgaard, B. (2019). The dubious role of institutions in international business: A road forward. Journal of International Business Studies, 50(1), 20–35.

Alcacer, J., & Ingram, P. (2013). Spanning the institutional abyss: The intergovernmental network and the governance of foreign direct investment. American Journal of Sociology, 118(4), 1055–1098.

Bergara, M. E., Henisz, W. J., & Spiller, P. T. (1998). Political institutions and electric utility investment: A cross-nation analysis. California Management Review, 40(2), 18–35.

Bhaumik, S. K., Estrin, S., & Narula, R. (2024). Integrating host-country political heterogeneity into MNE–state bargaining: Insights from international political economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 55(2), 157–171.

Boubakri, N., Mansi, S. A., & Saffar, W. (2013). Political institutions, connectedness, and corporate risk-taking. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(3), 195–215.

Cantwell, J., Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2010). An evolutionary approach to understanding international business activity: The co-evolution of MNEs and the institutional environment. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(4), 567–586.

Chacar, A. S., Newburry, W., & Vissa, B. (2010). Bringing institutions into performance persistence research: Exploring the impact of product, financial, and labor market institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1119–1140.

Chan, C. M., & Du, J. (2021). The dynamic process of pro-market reforms and foreign affiliate performance: When to seek local, subnational, or global help? Journal of International Business Studies, 52(9), 1854–1870.

Chari, M. D., & Chang, K. (2009). Determinants of the share of equity sought in cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8), 1277–1297.

Chen, D., Yu, X., & Zhang, Z. (2019). Foreign direct investment comovement and home country institutions. Journal of Business Research, 95(2), 220–231.

Chen, S.-F.S., & Hennart, J.-F. (2004). A hostage theory of joint ventures: Why do Japanese investors choose partial over full acquisitions to enter the United States? Journal of Business Research, 57(10), 1126–1134.

Chikhouni, A., Edwards, G., & Farashahi, M. (2017). Psychic distance and ownership in acquisitions: Direction matters. Journal of International Management, 23(1), 32–42.

Contractor, F. J., Lahiri, S., Elango, B., & Kundu, S. K. (2014). Institutional, cultural and industry related determinants of ownership choices in emerging market FDI acquisitions. International Business Review, 23(5), 931–941.

Cording, M., Christmann, P., & King, D. R. (2008). Reducing causal ambiguity in acquisition integration: Intermediate goals as mediators of integration decisions and acquisition performance. Academy of Management Journal, 51(4), 744–767.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2011). Global strategy and global business environment: The direct and indirect influences of the home country on a firm’s global strategy. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4), 382–386.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. (2016). Multilatinas as sources of new research insights: The learning and escape drivers of international expansion. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 1963–1972.

Cuypers, I. R., Ertug, G., & Hennart, J.-F. (2015). The effects of linguistic distance and lingua franca proficiency on the stake taken by acquirers in cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4), 429–442.

Elango, B., & Pattnaik, C. (2011). Learning before making the big leap: Acquisition strategies of emerging market firms. Management International Review, 51(4), 461–481.

Falaster, C., Ferreira, M. P., & Li, D. (2021). The influence of generalized and arbitrary institutional inefficiencies on the ownership decision in cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(9), 1724–1749.

Gautam, D. P. (2021). Does international migration impact economic institutions at home? European Journal of Political Economy, 69(2), 102007.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. European Economic Review, 35(2–3), 517–526.

Guler, I., & Guillén, M. F. (2010). Institutions and the internationalization of us venture capital firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 185–205.

Havranek, T., Horvath, R., & Zeynalov, A. (2016). Natural resources and economic growth: A meta-analysis. World Development, 88, 134–151.

Hayward, M. L. (2002). When do firms learn from their acquisition experience? Evidence from 1990 to 1995. Strategic Management Journal, 23(1), 21–39.

Hébert, L., Very, P., & Beamish, P. W. (2005). Expatriation as a bridge over troubled water: A knowledge-based perspective applied to cross-border acquisitions. Organization Studies, 26(10), 1455–1476.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–162.

Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics & Politics, 12(1), 1–31.

Hillman, A., & Wan, W. (2005). The determinants of MNE subsidiaries’ political strategies: Evidence of institutional duality. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 322–340.

Hitt, M. A., King, D. R., Krishnan, H., Makri, M., Schijven, M., Shimizu, K., & Zhu, H. (2012). Creating value through mergers and acquisitions: Challenges and opportunities. In D. Faulkner, S. Teerikangas, & R. J. Joseph (Eds.), The handbook of mergers and acquisitions (pp. 71–113). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hobdari, B., Gammeltoft, P., Li, J., & Meyer, K. (2017). The home country of the MNE: The case of emerging economy firms. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 34(1), 1–17.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Holburn, G. L., & Zelner, B. A. (2010). Political capabilities, policy risk, and international investment strategy: Evidence from the global electric power generation industry. Strategic Management Journal, 31(12), 1290–1315.

Holmes, R. M., Jr., Miller, T., Hitt, M. A., & Salmador, M. P. (2013). The interrelationships among informal institutions, formal institutions, and inward foreign direct investment. Journal of Management, 39(2), 531–566.

Jiménez, A. (2010). Does political risk affect the scope of the expansion abroad? Evidence from Spanish MNEs. International Business Review, 19(6), 619–633.

Kafouros, M. I., Buckley, P. J., & Clegg, J. (2014). The effects of global knowledge reservoirs on the productivity of multinational enterprises: The role of international depth and breadth. The Multinational Enterprise and The Emergence of The Global Factory, 220-254.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(3), 411–432.

Lahiri, S., Elango, B., & Kundu, S. K. (2014). Cross-border acquisition in services: Comparing ownership choice of developed and emerging economy MNEs in India. Journal of World Business, 49(3), 409–420.

Liou, R. S., Chao, M. C. H., & Ellstrand, A. (2017). Unpacking institutional distance: Addressing human capital development and emerging-market firms’ ownership strategy in an advanced economy. Thunderbird International Business Review, 59(3), 281–295.

Liou, R. S., Chao, M. C. H., & Yang, M. (2016). Emerging economies and institutional quality: Assessing the differential effects of institutional distances on ownership strategy. Journal of World Business, 51(4), 600–611.

Malhotra, S., Lin, X., & Farrell, C. (2016). Cross-national uncertainty and level of control in cross-border acquisitions: A comparison of Latin American and US multinationals. Journal of Business Research, 69(6), 1993–2004.

Marano, V., Arregle, J.-L., Hitt, M. A., Spadafora, E., & van Essen, M. (2016). Home country institutions and the internationalization-performance relationship: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 42(5), 1075–1110.

Meyer, K. E., Li, C., & Schotter, A. P. (2020). Managing the MNE subsidiary: Advancing a multi-level and dynamic research agenda. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), 538–576.

Moschieri, C., Ragozzino, R., & Campa, J. M. (2014). Does regional integration change the effects of country-level institutional barriers on M&A? The case of the European Union. Management International Review, 54(6), 853–877.

Murtha, T. P., & Lenway, S. A. (1994). Country capabilities and the strategic state: How national political institutions affect multinational corporations’ strategies. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S2), 113–129.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Oliver, C., & Holzinger, I. (2008). The effectiveness of strategic political management: A dynamic capabilities framework. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 496–520.

Ostrom, E. (2009). Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton University Press.

Pandya, S. S. (2016). Political economy of foreign direct investment: Globalized production in the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Political Science, 19(1), 455–475.

Park, B. I., & Choi, J. (2014). Control mechanisms of MNEs and absorption of foreign technology in cross-border acquisitions. International Business Review, 23(1), 130–144.

Piaskowska, D., & Trojanowski, G. (2014). Twice as smart? The importance of managers’ formative-years’ international experience for their international orientation and foreign acquisition decisions. British Journal of Management, 25(1), 40–57.

Pinto, C. F., Ferreira, M. P., Falaster, C., Fleury, M. T. L., & Fleury, A. (2017). Ownership in cross-border acquisitions and the role of government support. Journal of World Business, 52(4), 533–545.

Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advantage of nations: Harvard Business Review.